Abstract

Glomerular mesangial cell (GMC) proliferation and matrix expansion are pathological hallmarks of a wide range of kidney diseases, including diabetic nephropathy. Although the circulating level of peptide hormone urotensin II (UII) and kidney tissue expression of UII and UII receptors (UTR) are increased in diabetic nephropathy, it remains unclear whether UII regulates GMC growth and extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that UII-induced Ca2+ signaling controls GMC proliferation and ECM production under normal and high glucose conditions. Mouse GMCs cultured under normal glucose conditions proliferated and synthesized ECM proteins in response to stimulation by mouse UII. UII-induced GMC proliferation and ECM protein synthesis were dependent on TRPC4 channel-mediated store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) and sequential activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) and Ca2+/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) transcription factor. Under high glucose conditions, GMCs synthesized UII. Moreover, proliferation and ECM production in high glucose-challenged GMCs were attenuated by selective UTR antagonist, TRPC4 channel blocker, and CaMKII and CREB-binding protein/p300 inhibitors. These findings indicate that UII-induced SOCE via TRPC4 channels stimulates CaMKII/CREB-dependent GMC proliferation and ECM protein production. Our data also suggest that UII synthesis contributes to GMC proliferation and ECM accumulation under high glucose conditions.

Introduction

Experimental data from a variety of animal models suggest that peptide hormone urotensin II (UII) regulates renal functions, including vascular bed perfusion, glomerular filtration, and electrolyte homeostasis1–3. Alterations in UII and UII receptor (UTR) tissue expression and circulating and urinary levels of UII have been reported in human and experimental animals with cardiovascular and renal diseases, including hypertension, renal failure, congestive heart failure, atherosclerosis, renal fibrosis, glomerulonephritis, and diabetes1,2,4–8. Plasma and urinary concentrations of UII are elevated in proteinuric and non-proteinuric diabetic patients with progressive loss of renal functions4,7. Increased expressions of UII and UTR in kidney specimens from human and animals with diabetic nephropathy have also been reported5,8. However, the association between UII signaling and cellular events that underpin diabetic nephropathy is poorly understood.

The pathological hallmarks of diabetic nephropathy include glomerular ultrastructural changes, such as basement membrane thickening, extracellular matrix (ECM) accumulation, and mesangial expansion9,10. Increased mesangial expansion leads to encroachment of the Bowman’s space, obstruction of the glomerular capillaries, and progressive impairment of glomerular hemodynamics9,10. Exposure of cultured glomerular mesangial cell (GMCs) to high glucose concentrations induces proliferation, ECM protein synthesis, and hypertrophy, thereby mimicking the effect of hyperglycemia in diabetic nephropathy10,11. Mechanisms that underlie GMC responses to high glucose conditions are not fully resolved, but may include modulation of intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i), a major regulator of signaling pathways associated with cell cycle control12.

An increase in [Ca2+]i concentration can be triggered by an influx of extracellular Ca2+ into the cells via plasma membrane-localized Ca2+-permeable channels or Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores or both. Changes in [Ca2+]i is turned into biological responses by regulatory proteins that propagate Ca2+-sensitive signal transduction mechanisms such as protein phosphorylation and de-phosphorylation to the nucleus to influence gene transcription12,13. Like in many other cell types, Ca2+-sensitive transcription factors, such as the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, nuclear factor of activated T-cells, and Ca2+/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) control GMC survival14–16. High glucose stimulates CREB phosphorylation in GMCs17. Inhibition of [Ca2+]i elevation by Ca2+ channel blockers, inhibited proliferation, ECM protein synthesis, and CREB activity in GMCs14. Hence, CREB target genes are downstream effectors of Ca2+-dependent cellular events that promote GMC proliferation and ECM protein accumulation.

Ca2+-permeable ion channels that control glomerular function in health and disease include the transient receptor potential cation channels, subfamily C (TRPC). TRPC channels, comprising of seven members (TRPC1-7) function as Ca2+ release channels in excitable and non-excitable cells18. These channels contribute to Ca2+ signaling in GMCs, including store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE)19. SOCE occurs following endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+ store depletion and succeeding extracellular Ca2+ influx via store-operated Ca2+ channels20. TRPC4 constitutes store-operated Ca2+ channels in mouse GMCs21. TRPC4 can also interact with other TRPC isoforms and Ca2+ sensor stromal interaction molecule-1 (STIM1) to form signaling complexes that regulate SOCE in human GMCs22,23. UII-induced SOCE resulted in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation24. Our laboratory has also demonstrated that activation of UTR by UII stimulates SOCE in mouse GMCs25. However, it is unclear whether SOCE elicited by UII involves TRPC4 channels and controls GMC growth. Given that both UII production and mesangial expansion are associated with diabetic nephropathy4,7,9,10, we tested the hypothesis that UII-induced SOCE via TRPC4 channels modulates mouse GMC growth and ECM protein accumulation under normal and high glucose conditions.

Results

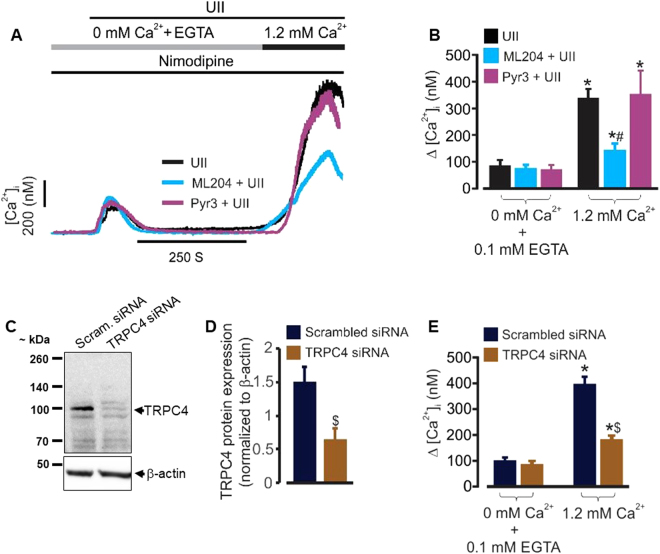

TRPC4 channels mediate UII-induced SOCE in mouse GMCs

To elucidate the role of TRPC4 channels in UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation, we first examined whether ML204, a selective TRPC4 channel blocker26 alters UII-induced SOCE in the cells. The effect of Pyr3, a selective TRPC3 channel blocker27 on UII-induced SOCE was also examined. In the absence of extracellular Ca2+, UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation was unaffected by ML204 and Pyr3 (Fig. 1A and B). However, UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation following extracellular Ca2+ re-addition (indicative of SOCE) was attenuated by ML204, but not, Pyr3 (Fig. 1A and B). Next, we measured SOCE in cells transfected with scrambled control and TRPC4 siRNAs. Transfection of GMCs with siRNA targeted to TRPC4 reduced its protein expression (Fig. 1C and D). Accordingly, TRPC4 channel knockdown attenuated UII-induced SOCE in the cells (Fig. 1E). These data indicate that UII-induced SOCE in mouse GMCs is dependent on TRPC4 channels.

Figure 1.

UII stimulates SOCE via TRPC4 channels in mouse GMCs. (A,B) Representative traces and mean data showing that UII (100 nM)-induced SOCE is attenuated by ML204 (0.5 µM; n = 7), but not, Pyr3 (1 µM; n = 4). (C,D) Western blot and mean data (n = 4 each) confirming siRNA-mediated knockdown of TRPC4 channels in mouse GMCs. (E) Mean data illustrating that siRNA-mediated knockdown of TRPC4 channels inhibits UII (100 nM)-induced SOCE in mouse GMCs [scrambled (Scram) control siRNA, n = 8; TRPC4 siRNA, n = 7]. The Ca2+ free solution was supplemented with EGTA (0.1 mM) to chelate Ca2+. To block L-type calcium channels, nimodipine (1 µM) was added to the bath solution. *P < 0.05 vs. 0 mM Ca2+ + 0.1 mM EGTA; #P < 0.05 vs. UII and Pyr3 + UII; $P < 0.05 vs TRPC4 siRNA.

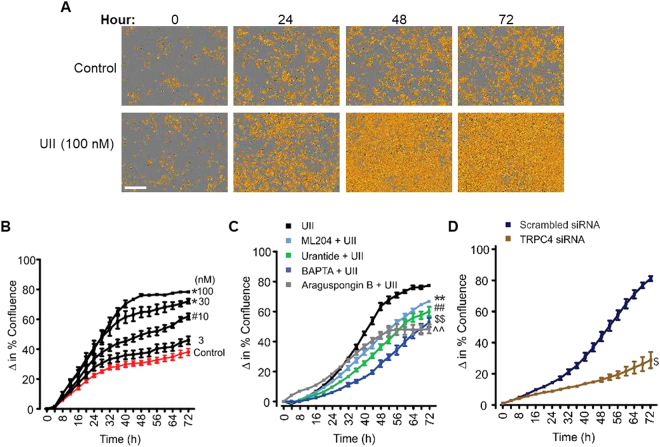

UII-induced SOCE via TRPC4 channels promotes mouse GMC proliferation

To examine whether UII-induced Ca2+ signaling controls GMC growth, cell growth kinetics were assessed in real-time. Cell growth curves automatically quantified over 72 h showed that UII increased GMC confluence in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Fig. 2A,B). Significant increases in cell confluence commenced ~24 h following UII treatment (Fig. 2A,B). Furthermore, we tested the hypothesis that UTR activation and succeeding SOCE via TRPC4 channels contribute to UII-induced GMC proliferation. Selective UTR antagonist urantide, TRPC4 channel blocker ML204, inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor antagonist araguspongin B, and [Ca2+]i chelator BAPTA, all attenuated UII-induced GMC proliferation (Fig. 2C). Similarly, TRPC4 knockdown diminished the proliferative effect of UII in the cells (Fig. 2D). These results signify that UII-induced SOCE via TRPC4 channels and subsequent [Ca2+]i elevation elicit GMC proliferation.

Figure 2.

UII-induced SOCE via TRPC4 channels promotes mouse GMC proliferation. (A) Phase contrast images demonstrating cell density in control and UII-treated GMCs. (B) Cell growth curves showing time- and concentration-dependent proliferative effect of UII (n = 4 each) in mouse GMCs. (C,D) Cell growth curves indicating that UII (100 nM; n = 4)-induced GMC proliferation is attenuated by urantide (1 µM; n = 5), ML204 (100 nM; n = 5), BAPTA (2 µM; n = 5), araguspongin B (3 µM; n = 5), and siRNA-mediated knockdown of TRPC4 channels (control and TRPC4 siRNA, n = 4 each). “n” for cell proliferation assay denotes number of wells. Each time point represents 4 independent scans per well of the microplates. #P < 0.05 vs. control (24–72 h); *P < 0.05 vs. control (20–72 h); **P < 0.05 vs. UII (34–72 h); ##P < 0.05 vs. UII (26–72 h); $$P < 0.05 vs. UII (22–72 h); ^^P < 0.05 vs. UII (38–72 h); $P < 0.05 vs. TRPC4 siRNA (32–72 h); Scale bar = 300 µm.

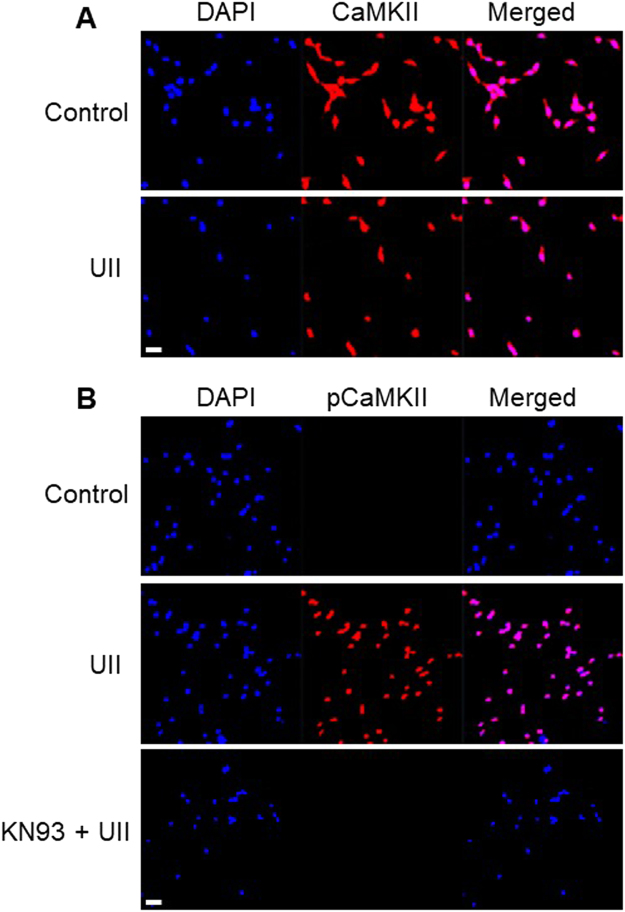

UII activates Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) II phosphorylation in mouse GMCs

To study the mechanisms that underlie UII-induced GMC growth, we examined Ca2+-sensitive intracellular signaling proteins that are regulated by UII. First, we investigated whether UII stimulates CaMKII phosphorylation in the cells. CaMKII activation is elicited by binding of Ca2+/calmodulin to the regulatory domain of the kinase thereby resulting in phosphorylation at Thr286 28. Confocal microscopy demonstrated localization of total endogenous CaMKII in control and cells treated with UII (Fig. 3A). Unlike the untreated cells, phosphorylated CaMKII (pCaMKII; Thr286) immunostaining was detected in cells treated with UII, an effect abolished by KN-93, a CaMKII inhibitor (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that UII induces CaMKII phosphorylation in GMCs.

Figure 3.

UII activates CaMKII phosphorylation in mouse GMCs. Confocal microscopy of mouse GMCs showing that: (A) Total endogenous CaMKII is immunostained in untreated and treated cells (100 nM UII for 5 min), (B) Unlike untreated cells, pCaMKII Thr286 immunostaining was detected in cells incubated with UII, an effect abolished by KN-93 (2 µM). Images are representative of 3-4 randomly chosen fields from 3-4 coverslips per experimental condition. Scale bar = 100 µm.

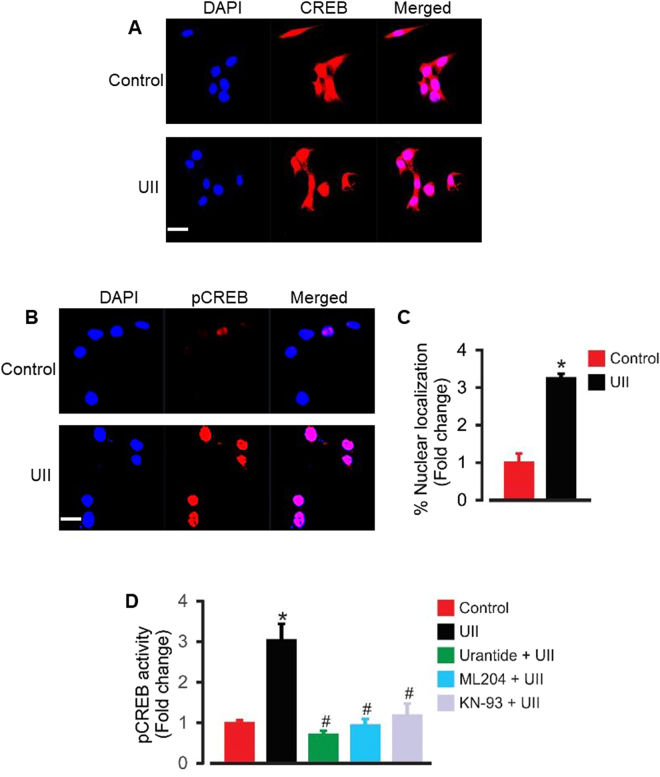

UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII activation stimulate nuclear pCREB activity in mouse GMCs

An elevation in [Ca2+]i contributes to the regulation of transcriptional factors that control cell cycle, including CREB29. CREB activation is involved in GMC proliferation14,17. Given that CREB (at Ser133) is a substrate for CaMKII-induced phosphorylation30, we investigated the hypothesis that UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII activation stimulate nuclear pCREB activity in GMCs. Immunofluorescence staining showed that endogenous CREB was unchanged in control and cells treated with UII (Fig. 4A). However, UII treatment caused a ~3-fold increase in nuclear pCREB Ser133 immunostaining (Fig. 4B and C). Similarly, UII increased pCREB binding activity ~3-fold in GMC nuclear extracts (Fig. 4D). UII-induced nuclear pCREB binding activity was inhibited by urantide, ML204, and KN-93 (Fig. 4D). These data suggest that UII-evoked [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII induction promote pCREB activation in GMCs.

Figure 4.

UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII activation stimulates nuclear pCREB activity in mouse GMCs. (A,B) Confocal microscopy showing localization of endogenous CREB and pCREB in control and UII (100 nM)-treated GMCs. (C) Mean data showing that treatment of mouse GMCs with UII (100 nM) for 4 h increased nuclear pCREB immunostaining (n = 20 randomly chosen fields from 3–4 coverslips per experimental condition). (D) Mean data from pCREB transcription factor activity assay illustrating that UII (100 nM) increased GMC nuclear pCREB binding activity ~3-fold, an effect inhibited by urantide (1 µM), ML204 (100 nM), and KN-93 (2 µM); n = 5 each. *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. UII. Scale bar = 20 µm.

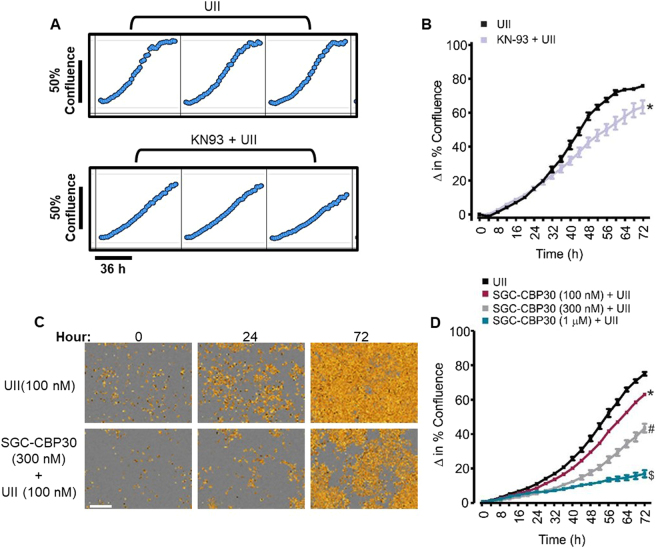

UII-induced GMC proliferation is dependent on CaMKII activation and CREB coactivators CREB binding protein (CBP) and E1A binding protein p300 (p300)

To study the role of CaMKII and CREB in UII-induced GMC proliferation, we examined cell growth in GMCs pretreated with a CaMKII inhibitor. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, KN-93 significantly reduced UII-induced GMC proliferation. Induction of CREB target genes involves the recruitment of CREB coactivators CBP and p30031,32. Hence, we explored the effect of SGC-CBP30, a selective CBP/p300 inhibitor33,34 on UII-induced GMC growth. SGC-CBP30 concentration-dependently attenuated UII-induced GMC proliferation (Fig. 5C,D). These findings suggest the involvement of CaMKII activation and CREB co-activators in GMC growth elicited by UII.

Figure 5.

UII-induced GMC proliferation is dependent on CaMKII activation and CREB co-activators CBP/p300. (A) Microplate graphs, and (B) Cell growth curves demonstrating that UII (100 nM; n = 5)-induced mouse GMC proliferation is inhibited by KN-93 (2 µM; n = 5). (C) Phase contrast images, and (D) Cell growth curves indicating that inhibition of CREB co-activators CBP and p300 by SGC-CBP30 diminished UII (100 nM)-induced GMC proliferation (n = 4 each). “n” for cell proliferation assay denotes the number of wells. Each time point represents four independent scans per well of the microplates. *P < 0.05 vs. control (40-72 h); #P < 0.05 vs. control (22–72 hr); $P < 0.05 vs. control (26–72 hr). Scale bar = 300 µm.

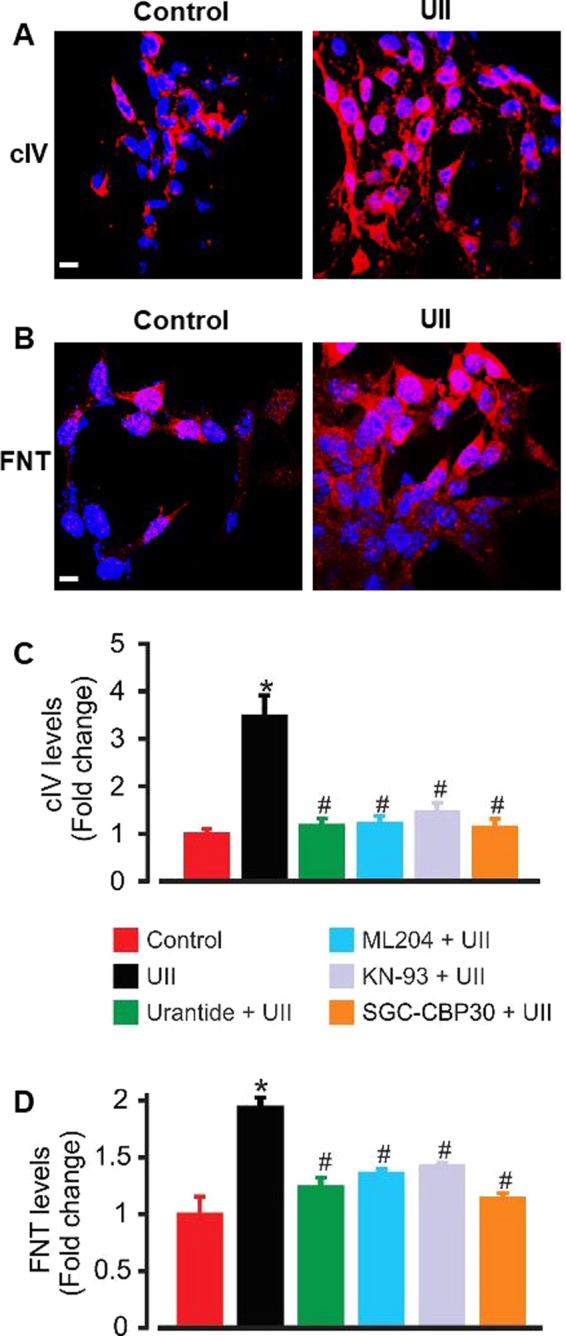

UII-induced SOCE and CaMKII/CREB activation increase type IV collagen and fibronectin production in mouse GMCs

Next, we investigated the hypothesis that UII stimulates ECM protein synthesis in GMCs. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, GMCs that were immunostained for type IV collagen and fibronectin showed higher levels of the proteins in UII-treated (72 h) cells when compared with untreated cells. Also, type IV collagen and fibronectin concentrations in cell culture supernatants were increased ~3- and 2-fold, respectively in cells treated with UII for 72 h (Fig. 6C,D). UII-induced type IV collagen and fibronectin syntheses were inhibited by urantide, ML204, KN-93, and SGC-CBP30 (Fig. 6C and D). These data indicate that UII-induced SOCE and CaMKII/CREB activation increases ECM protein production in GMCs.

Figure 6.

UII-induced Ca2+ and CaMKII/CREB signaling increases type IV collagen (cIV) and fibronectin (FNT) accumulation in mouse GMCs. (A,B) ECM proteins cIV and FNT staining showed higher levels of the proteins in UII (100 nM; 72 h)-treated cells when compared with untreated cells (Images are representative of 3–4 coverslips). (C,D) Mean data obtained from ELISA illustrating that cIV and FNT productions are increased ~3- and 2-folds, respectively in supernatants of UII (100 nM)-treated GMCs, and that UII-induced cIV and FNT syntheses are inhibited by urantide (1 µM), ML204 (100 nM), KN-93 (2 µM), and SGC-CBP30 (1 µM). For FNT, n = 5 per experimental condition. For cIV, n = 6 (control, urantide, ML204, KN-93, and SGC-CBP30), and 12 (UII). *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. UII.

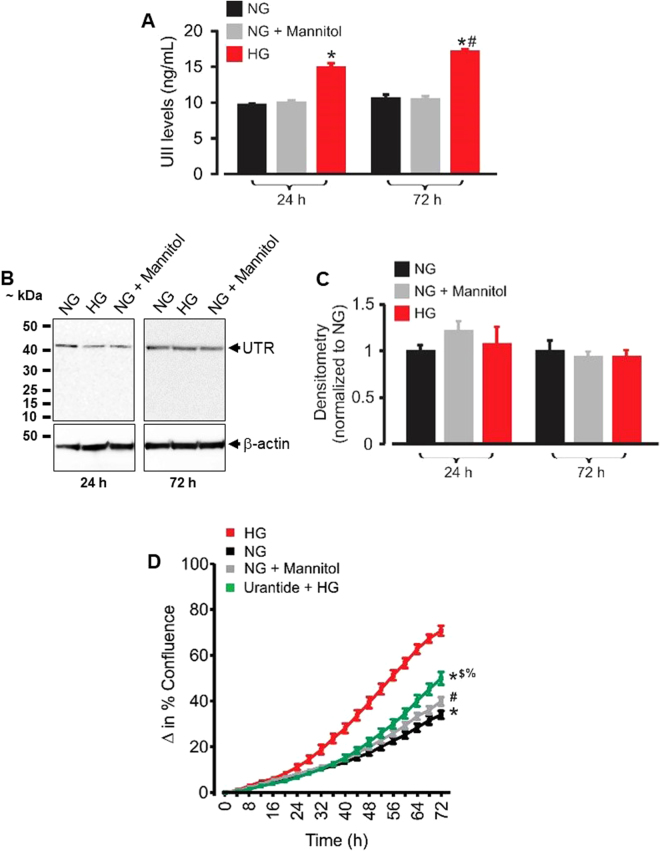

High glucose-induced UII synthesis promotes mouse GMC proliferation

Since UII levels and UTR expression are increased in diabetic nephropathy4,5,7,8, it is likely that GMC proliferation under hyperglycemic conditions is associated with the UII/UTR system. To investigate this concept, we first used a mouse UII ELISA kit to measure the concentration of UII in supernatants of GMCs cultured for 24 and 72 h in high (25 mM) glucose DMEM to mimic hyperglycemic conditions typical of diabetic mice35,36. As an osmotic control, normal (5.5 mM) glucose-containing DMEM was supplemented with 19.5 mM mannitol. As shown in Fig. 7A, exposure of the cells to high glucose DMEM for 24 and 72 h increased UII concentration in the culture supernatants by ~35 and 39%, respectively. By contrast, UII levels were unchanged in cells cultured in osmotic control medium (Fig. 7A). Western blot analysis indicated that UTR protein expression is unaltered in GMCs that were cultured in high glucose DMEM for 24–72 h (Fig. 7B and C). Unlike the osmotic control, high glucose increased GMC proliferation in a time-dependent fashion (Fig. 7D). Remarkably, high glucose-induced GMC proliferation was attenuated by UTR antagonist urantide (Fig. 7D). These results suggest that an increase in UII production under high glucose conditions, and the resultant activation of UTR induces GMC proliferation.

Figure 7.

High glucose-induced UII synthesis contributes to GMC proliferation. (A) Mean data obtained from mouse UII ELISA showing that exposure of mouse GMCs to high glucose for 24 (n = 6 each) and 72 (n = 9 each) h increases UII production. (B,C) Western blot and mean data illustrating that exposure of mouse GMCs to high glucose for 24 and 72 h (n = 5 each) does not alter UTR protein expression. (D) Cell growth curves demonstrating GMC proliferation under normal glucose (n = 6), normal glucose + mannitol (n = 6), high glucose (n = 6) and urantide (1 µM) + high glucose (n = 6). “n” for cell proliferation assay denotes number of wells. Each time point represents four independent scans per well of the microplates. *P < 0.05 vs. HG (30–72 h); #P < 0.05 vs. HG; (32–72 h); $P < 0.05 vs. NG (54–72 h); %P < 0.05 vs. NG + mannitol (62–72 h). HG (high glucose); NG (normal glucose).

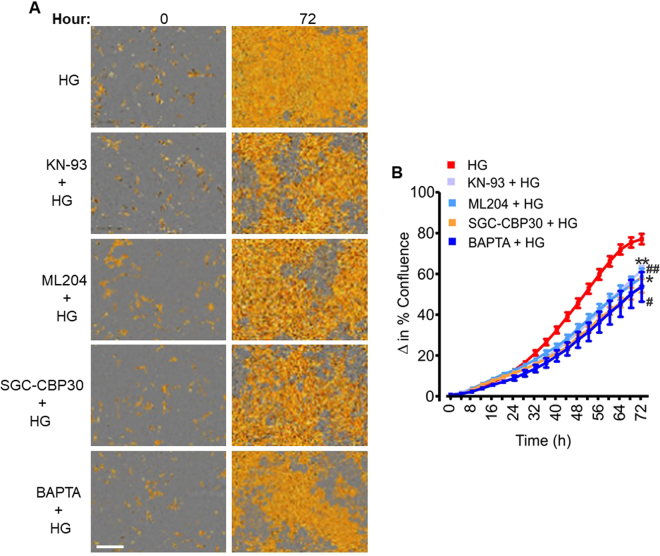

TRPC4-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII/CREB activation contribute to high glucose-induced mouse GMC proliferation

To examine whether TRPC4-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII/CREB activation are involved in high glucose-induced GMC proliferation, we studied GMC growth in cells pretreated with a TRPC4 channel blocker and inhibitors of CaMKII and CREB coactivators. High glucose-induced GMC proliferation was attenuated by ML204, KN-93, SGC-CBP30, and BAPTA (Fig. 8A and B), indicating that TRPC4-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII/CREB activation contribute to high glucose-induced GMC proliferation.

Figure 8.

TRPC4-dependent [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII/CREB activation contribute to high glucose-induced GMC proliferation. (A) Phase contrast images, and (B) Cell growth curves showing that high glucose-induced mouse GMC proliferation is reduced by ML204 (100 nM), BAPTA (2 µM), KN-93 (2 µM), and SGC-CBP30 (1 µM). n = 10 each; “n” denotes the number of wells. Each time point represents four independent scans per well of the microplates. **P < 0.05 vs. HG (42–72 h); ##P < 0.05 vs. HG (44–72 hr); *P < 0.05 vs. HG (38–72 hr); #P < 0.05 vs. HG (36–72 hr); Scale bar = 300 µm. HG (high glucose); NG (normal glucose).

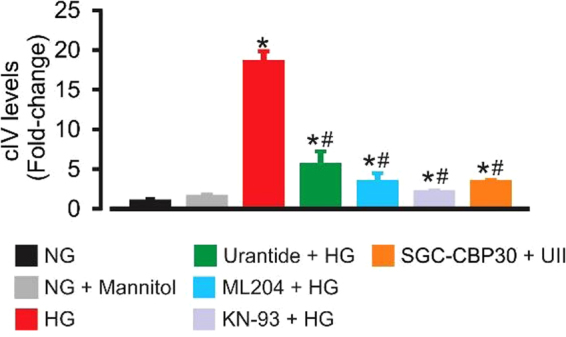

UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII/CREB activation contribute to ECM accumulation under high glucose conditions

High glucose increased type IV collagen level in GMC culture supernatants ~19-fold (Fig. 9). High glucose-induced type IV collagen production was attenuated in cells pretreated with urantide, ML204, KN-93, and SGC-CBP30 (Fig. 9). Collectively, our data suggest that UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation via TRPC4 channels, and successive activation of the CaMKII/CREB signal transduction pathway contribute to proliferation and ECM protein synthesis in high glucose-challenged GMCs (Fig. 10).

Figure 9.

UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation and CaMKII/CREB activation contribute to ECM protein production under high glucose conditions. Mean data obtained from ELISA showing that high glucose-induced type IV collagen production is mitigated by urantide (1 µM), ML204 (100 nM), KN-93 (2 µM), and SGC-CBP30 (1 µM). n = 6 (NG, NG + mannitol, ML204 + HG, KN-93 + HG, and SGC-CBP30 + HG) n = 10 (HG and urantide + HG); *P < 0.05 vs. NG and NG + mannitol; #P < 0.05 vs. HG. HG (high glucose); NG (normal glucose); type IV collagen (cIV).

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram illustrating hypothetical mechanisms by which UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation via TRPC4 channels, and successive activation of CaMKII/CREB signaling pathways contribute to proliferation and ECM protein accumulation in high glucose-challenged GMCs. Other molecular components of store-operated Ca2+ entry, including STIM1 and Orai1 may contribute to these mechanisms.

Discussion

Although studies have shown that renal UII production may be associated with diabetic nephropathy1,4,5,7, little is known about the function of UII in renal glomerulus in health and disease. The findings presented in this study are the first indication that UII-induced [Ca2+]i elevation stimulates GMC proliferation and ECM protein production. Our data also suggest that UII is synthesized by GMCs under high glucose conditions, and that high glucose-induced GMC proliferation and ECM protein accumulation are dependent, at least in part, on UII-mediated Ca2+ signaling. We thus provide a novel insight into the cellular mechanisms that may contribute to glomerular dysregulation caused by hyperglycemia.

A previous study reported that TRPC4 channel knockdown attenuated SOCE in mouse GMCs by ~83%, indicating that TRPC4 forms store-operated Ca2+ channels in the cells21. UTR, a Gq/11 protein-coupled receptor is expressed in mouse GMCs25. Activation of UTR by UII in mouse GMCs stimulated phospholipase C/ IP3-dependent ER Ca2+ release, resulting in SOCE25. Whether TRPC4 mediates UII-induced SOCE in mouse GMCs was unknown. To delineate the role of TRPC4 in UII-induced SOCE we first studied the effect of ML204, its selective pore blocker26. We show that unlike TRPC3 channel blocker Pyr3, a nanomolar concentration of ML204 attenuated UII-induced SOCE. Likewise, SOCE triggered by UII was reduced in cells transfected with TRPC4 siRNA. In rat podocytes, ML204 stimulated Ca2+ release from the intracellular stores, but this effect occurred at a concentration 40 times higher than what we used in this study37. ML204 can also block TRPC5 channels, albeit at higher concentrations compared with TRPC426. Moreover, TRPC5 is not expressed in mouse GMCs21. Hence, the effects of ML204 reported here are independent of TRPC5 channels. Together, our data demonstrate that activation of UTR by UII triggers SOCE via TRPC4 channels, resulting in an increase in [Ca2+]i concentration in mouse GMCs. UII-induced SOCE in rat coronary artery smooth muscle cells is mediated by STIM1 and Ca2+ release-activated calcium channel (Orai1) protein complex38. Similarly, STIM1, Orai1, and TRPC1 contribute to UII-induced SOCE in aortic smooth muscle cells24. In human GMCs, SOCE is dependent on protein complexes, including TRPC1, 4, and STIM122. Whether UII-induced TRPC4 activation in mouse GMCs involve its association with TRPC1, STIM1, or Orai1 is not addressed in this study and requires further investigation.

Our data show that CaMKII and CREB phosphorylation are sequential downstream targets of TRPC4-mediated [Ca2+]i elevation stimulated by UII in mouse GMCs. Activation of CaMKII and CREB phosphorylation is required for UII-induced vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation24. Since UII stimulates CaMKII and CREB phosphorylation via TRPC4-mediated SOCE in mouse GMCs, we investigated the concept that UII-induced GMC proliferation involves CaMKII/CREB activation. We show that at the concentration that prevented UII-induced CaMKII phosphorylation, KN-93 attenuated UII-induced nuclear pCREB binding activity and proliferation in the cells. CREB, a ubiquitous transcription factor controls a wide variety of cellular processes, including GMC survival and ECM protein synthesis14,39. Phosphorylation of CREB on Ser133 stimulates its interaction with coactivators CBP or its homolog p300, leading to target gene activation31,32. CBP/p300 induction promotes cellular apoptosis, proliferation, and development40. In rat GMCs, angiotensin II-induced fibronectin upregulation involves activation of CREB and p30041. Here, we show that pharmacological inhibition of the CBP/p300 bromodomain33,34 suppressed GMC growth in UII-treated cells. These data suggest the involvement of CBP/p300-dependent gene transcription in UII-induced GMC proliferation. Corresponding to its effect on cell number, UII increased type IV collagen and fibronectin secretion by GMCs. Immunofluorescence staining of type IV collagen and fibronectin also indicated that UII stimulates their production by individual cells. These data are consistent with studies that reported an increase in fibronectin and collagen mRNA expression in rat proximal tubular epithelial cells and cardiac fibroblasts treated with UII42,43. Thus, a combination of increased proliferation and synthesis by individual GMCs may account for UII-induced ECM accumulation. Our data suggest that UII-induced ECM protein production is dependent on TRPC4 channels, CaMKII, and CBP/p300. Together, our findings highlight the contribution of TRPC4-mediated SOCE and CaMKII/CREB activation to increased growth and ECM production in UII-treated GMCs. CBP/p300 can interact with other transcription factors, such as members of the activator protein 1 (AP-1) family, including c-Fos and c-Jun40. Decoy oligodeoxynucleotides targeting AP-1 suppressed high glucose- and angiotensin II-induced rat GMC proliferation and matrix gene expression44. Other studies have demonstrated the importance of c-Fos and c-Jun in GMC proliferation45,46. Given the molecular and functional crosstalk between CREB and AP-1 signaling pathways39,47, UII-induced CREB activation and downstream GMC proliferation and ECM accumulation may involve AP-1 components.

We present novel findings indicating that mouse GMCs synthesize UII when cultured under high glucose conditions. Mechanisms by which high glucose stimulates UII production is unclear but may involve increased proteolytic processing or expression of UII precursor prepro-UII. However, this speculation requires further investigations. Exposure of cultured GMCs to high glucose increases proliferation and accumulation of ECM proteins, especially, type IV collagen and fibronectin, thereby mimicking phenotypic changes in diabetic glomeruli9–11. Data here suggest that GMC proliferation and ECM protein accumulation triggered by a high glucose concentration are dependent on UTR, TRPC4 channels, and CaMKII/CREB pathways. These findings are significant because the circulating level and kidney expression of UII are increased in human diabetic nephropathy4,5,7. Thus, increased production of UII in diabetes may contribute to mesangial expansion and glomerular derangement. UTR expression in the kidney is upregulated in human and animals with diabetic nephropathy5,8. However, we did not observe an increase in UTR protein expression in GMCs exposed to high glucose for 24 and 72 h. Apart from GMCs, UTR is expressed in other locations in the kidney, including collecting ducts, proximal and distal tubules, and blood vessels1,3. Hence, other renal cell types may contribute to the increased kidney tissue expression of UTR in diabetes. It is also possible that prolonged exposure of cultured GMCs to high glucose is required to alter UTR protein expression.

Blockade of TRPC4 channels inhibited UII-induced SOCE, CREB activation, proliferation, and ECM production in GMCs. Similarly, TRPC4 channel inhibition attenuated high glucose-induced GMC growth and type IV collagen synthesis. Together, these data indicate that SOCE stimulated by UII contributes to high glucose-induced GMC proliferation and ECM protein accumulation. A recent study reported that activation of SOCE by thapsigargin abolished fibronectin and type IV collagen protein expression in human GMCs cultured in a high glucose medium, suggesting that SOCE elicited by thapsigargin negates ECM accumulation in GMCs48. However, unlike UII, thapsigargin-induced [Ca2+]i elevation inhibited proliferation and triggered apoptosis in GMCs49. The intracellular effectors of thapsigargin-induced SOCE in GMCs are unclear. Thus, it is likely that the effects of SOCE-mediated signal transductions on GMC survival and ECM protein production are dependent on the stimulant, the level of [Ca2+]i increase, or downstream Ca2+ sensitive signal transduction cascades that are activated. Acute exposure of rat GMCs to high glucose increased [Ca2+]i concentration by a mechanism that partly involves the store-operated Ca2+ channels50. Cyclopiazonic acid- and IP3- induced SOCE and store-operated Ca2+ currents, respectively have also been shown to be amplified in human GMCs under chronic high glucose treatment, and associated with increased protein expression of STIM1 and Orai151. These studies suggest that additional mechanisms of high-glucose-induced modulation of GMC function may involve direct alterations in basal [Ca2+]i levels or expression of the molecular components of the store-operated Ca2+ channels.

In conclusion, we present new findings demonstrating that UII-induced Ca2+ signaling promotes CaMKII/CREB-dependent proliferation and ECM protein production in GMCs. Our data also suggest that high glucose elicits UII synthesis, which in turn induces CaMKII/CREB-dependent proliferation and ECM protein production in the cells. Conceivably, increased UII production in GMCs and the resultant proliferation and ECM protein accumulation are involved in the pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie mesangial expansion in diabetic nephropathy.

Methods

GMC culture

The use of GMC lines was approved, and experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Institutional Biosafety Committee of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center. Mouse GMC line (CRL-1927) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were subcultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

[Ca2+]i imaging

[Ca2+]i concentration was measured in GMCs using the ratiometric Ca2+ indicator Fura-2 AM, as we have previously done25,52,53. Briefly, mouse GMCs cultured in glass-bottom dishes were loaded with Fura-2 AM (10 μM) and 0.5% pluronic F-127 for ~1 h at room temperature. Cells were then washed with modified Krebs’ solution (MKS; 134 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 10 mM glucose, pH 7.4) for ~30 min to de-esterify Fura-2 AM molecules. Changes in intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) was measured at room temperature with a ratiometric Ca2+ imaging system (Ionoptix Corp., Milton, MA, USA). Fura-2 AM fluorescence was recorded by using a hyperswitch light source (Ionoptix) to excite at wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm. The fluorescence was collected simultaneously from cells located in one imaging field per dish. Fura-2 AM ratios were background-subtracted and collected at 510 nm using a MyoCam-S CCD digital camera (Ionoptix). Data were then analyzed with the IonWizard software (Ionoptix).

siRNA transfection

siRNA transfection was performed using the BTX ECM 830 square wave electroporator (BTX, Holliston, MA). Cells (~106) in 100 µl of antibiotic-free DMEM and a pool of 3 target-specific TRPC4 siRNAs (~1 µg) or a non-targeting scrambled control siRNA (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) were electroporated in cuvettes for 100 milliseconds at 150 V. Following recovery (~10 min at room temperature), cells were transferred into flasks or microplates and cultured for 72 hours. Western immunoblotting was used to confirm knockdown efficiency.

Western immunoblotting

Total protein was isolated from cultured GMCs using the RIPA lysis buffer. Protein concentrations were then quantified using an assay kit and SmartSpec 3000 Spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Denatured proteins (LDS sample buffer + DTT and heated at 70 °C for 10 min) were separated on polyacrylamide gels in a Mini Trans Blot Cell (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes using a Pierce Fast Semi-Dry Blotter (Thermo Scientific). Nonspecific binding sites on the membranes were blocked for ~1 h using Tris Buffered Saline supplemented with 0.05% Tween (TBS-T) and 5% nonfat milk. The membranes were probed with respective primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. After a wash in TBS-T, the membranes were incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 45 min at room temperature. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized on a Kodak gel imaging system using the femtoLUCENT PLUS-HRP chemiluminescent reagent (G-Biosciences).

Live content microscopy of GMC growth and immunofluorescence staining

GMC growth was studied using live content microscopy as we have previously described52,53. GMCs plated in flat-bottom tissue culture microplates (~1 × 104/well) were starved overnight by culturing in DMEM that contained 0.1% FBS. The cells were then placed in a chamber apparatus of the IncuCyte ZOOM live content microscopy system (Essen Instruments, Ann Arbor, MI) in an incubator. GMC growth was monitored in real-time and quantified from cell confluence changes automatically acquired at two-hourly intervals by the IncuCyte cell density detection software and interface. Phase contrast images (segmentation mask illustrated in goldenrod) demonstrating cell density were also acquired with the IncuCyte software.

For immunofluorescence staining, cells that were sparsely grown on glass coverslips were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for ~20 min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for ~15 min at room temperature. Non-specific binding sites in the cells were blocked for 1 h by incubation in MAXblock blocking medium (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). The cells were then treated overnight at 4 °C with respective primary antibodies. Next day, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with cross-adsorbed Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) for 1 hour at room temperature. Following a wash and mount, fluorescence images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 710 laser-scanning confocal microscope.

Phospho-CREB (pCREB; Ser133) staining and DNA binding activity

To determine nuclear immunoreactivity of pCREB, the total number of pCREB positive nuclei were counted in randomly-selected microscopic fields and expressed as the percentage of the total number of DAPI-stained nuclei in the same fields. The pCREB transcription factor assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) was used to detect pCREB activity in GMC nuclear extracts. GMC nuclear proteins were extracted using a nuclear extraction kit (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO). pCREB DNA binding activity in nuclear extracts (5 μg protein/well) was determined according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of type IV collagen, fibronectin, and UII production

Cultured GMCs (106/microplate well) were starved overnight. Thereafter, the cells were treated with respective test substances and cultured for 24–72 hours. Type IV collagen, fibronectin, and UII concentrations in cell culture supernatants were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits purchased from Exocell Inc. (Philadelphia, PA), ScienCell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA), and BioTrend Chemicals, LLC (Destin, FL), respectively.

Antibodies and chemicals

Mouse monoclonal anti-actin and anti-TRPC4 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and Antibodies Inc. (Davis, CA), respectively. Rabbit polyclonal anti-CaMKII, -pCaMKII, and -pCREB were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-collagen IV and -fibronectin were obtained from Bioss Inc. (Woburn, MA). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibodies were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA) and Abcam, respectively. Cross-adsorbed Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rabbit was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Fura-2 AM, Pluronic F-127, mouse UII, urantide, β-mercaptoethanol, SGC-CBP30, and Pyr3 were purchased from Life Technologies, AnaSpec (Fremont, CA), Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Burlingame, CA), Peptides International, Inc. (Louisville, Kentucky), Bio-Rad, Tocris Bioscience (Bristol UK), and Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI), respectively.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Data were analyzed using the InStat software (Graph Pad, Sacramento, CA). Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-tests for paired or unpaired data and analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Craig Lindsley of the Vanderbilt Specialized Chemistry Center for providing ML204. This study is supported by funds from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Author Contributions

H.S. and A.A. designed and conducted the experiments and analyzed the data. A.A. conceived the study, directed the project, and wrote the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ashton N. Renal and vascular actions of urotensin II. Kidney Int. 2006;70:624–629. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douglas SA, Dhanak D, Johns DG. From ‘gills to pills’: urotensin-II as a regulator of mammalian cardiorenal function. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;25:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soni H, Adebiyi A. Pressor and renal regional hemodynamic effects of urotensin II in neonatal pigs. J. Endocrinol. 2013;217:317–326. doi: 10.1530/JOE-12-0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Totsune K, et al. Elevated plasma levels of immunoreactive urotensin II and its increased urinary excretion in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus: association with progress of diabetic nephropathy. Peptides. 2004;25:1809–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langham RG, et al. Increased expression of urotensin II and urotensin II receptor in human diabetic nephropathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2004;44:826–831. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(04)01130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balat A, Karakok M, Yilmaz K, Kibar Y. Urotensin-II immunoreactivity in children with chronic glomerulonephritis. Ren Fail. 2007;29:573–578. doi: 10.1080/08860220701392108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Totsune K, et al. Increased plasma urotensin II levels in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin. Sci. (Lond) 2003;104:1–5. doi: 10.1042/cs1040001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian L, et al. Diabetes-induced upregulation of urotensin II and its receptor plays an important role in TGF-beta1-mediated renal fibrosis and dysfunction. Am. J Physiol Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;295:E1234–E1242. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90672.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steffes MW, Osterby R, Chavers B, Mauer SM. Mesangial expansion as a central mechanism for loss of kidney function in diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1989;38:1077–1081. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.9.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mason RM, Wahab NA. Extracellular matrix metabolism in diabetic nephropathy. J Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:1358–1373. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000065640.77499.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayo SH, et al. Increased extracellular matrix synthesis and mRNA in mesangial cells grown in high-glucose medium. Am. J Physiol. 1991;260:F185–F191. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.260.2.F185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kahl CR, Means AR. Regulation of cell cycle progression by calcium/calmodulin-dependent pathways. Endocr. Rev. 2003;24:719–736. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrisani OM. CREB-mediated transcriptional control. Crit Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 1999;9:19–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sugiura T, Imai E, Moriyama T, Horio M, Hori M. Calcium channel blockers inhibit proliferation and matrix production in rat mesangial cells: possible mechanism of suppression of AP-1 and CREB activities. Nephron. 2000;85:71–80. doi: 10.1159/000045633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lan T, et al. Berberine attenuates high glucose-induced proliferation and extracellular matrix accumulation in mesangial cells: involvement of suppression of cell cycle progression and NF-kappaB/AP-1 pathways. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2014;384:109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gooch JL, Tang Y, Ricono JM, Abboud HE. Insulin-like growth factor-I induces renal cell hypertrophy via a calcineurin-dependent mechanism. J Biol. Chem. 2001;276:42492–42500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102994200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahab NA, Parker S, Sraer JD, Mason RM. The decorin high glucose response element and mechanism of its activation in human mesangial cells. J Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2000;11:1607–1619. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1191607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clapham DE. TRP channels as cellular sensors. Nature. 2003;426:517–524. doi: 10.1038/nature02196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma R, Du J, Sours S, Ding M. Store-operated Ca2+ channel in renal microcirculation and glomeruli. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood.) 2006;231:145–153. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr. Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Pluznick JL, Wei P, Padanilam BJ, Sansom SC. TRPC4 forms store-operated Ca2+ channels in mouse mesangial cells. Am. J. Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C357–C364. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00068.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sours-Brothers S, Ding M, Graham S, Ma R. Interaction between TRPC1/TRPC4 assembly and STIM1 contributes to store-operated Ca2+ entry in mesangial cells. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2009;234:673–682. doi: 10.3181/0809-RM-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Pluznick JL, Settles DC, Sansom SC. Association of VASP with TRPC4 in PKG-mediated inhibition of the store-operated calcium response in mesangial cells. Am. J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1768–1776. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00365.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez-Moyano M, et al. Urotensin-II promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through store-operated calcium entry and EGFR transactivation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2013;100:297–306. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adebiyi A. RGS2 regulates urotensin II-induced intracellular Ca2+ elevation and contraction in glomerular mesangial cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2014;229:502–511. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller M, et al. Identification of ML204, a novel potent antagonist that selectively modulates native TRPC4/C5 ion channels. J Biol. Chem. 2011;286:33436–33446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiyonaka S, et al. Selective and direct inhibition of TRPC3 channels underlies biological activities of a pyrazole compound. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5400–5405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808793106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stratton MM, Chao LH, Schulman H, Kuriyan J. Structural studies on the regulation of Ca2+/calmodulin dependent protein kinase II. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013;23:292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machaca K. Ca2+ signaling, genes and the cell cycle. Cell Calcium. 2010;48:243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheng M, Thompson MA, Greenberg ME. CREB: a Ca2+-regulated transcription factor phosphorylated by calmodulin-dependent kinases. Science. 1991;252:1427–1430. doi: 10.1126/science.1646483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwok RP, et al. Nuclear protein CBP is a coactivator for the transcription factor CREB. Nature. 1994;370:223–226. doi: 10.1038/370223a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cardinaux JR, et al. Recruitment of CREB binding protein is sufficient for CREB-mediated gene activation. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;20:1546–1552. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.5.1546-1552.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammitzsch A, et al. CBP30, a selective CBP/p300 bromodomain inhibitor, suppresses human Th17 responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:10768–10773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1501956112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hay DA, et al. Discovery and optimization of small-molecule ligands for the CBP/p300 bromodomains. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:9308–9319. doi: 10.1021/ja412434f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breyer MD, et al. Mouse models of diabetic nephropathy. J Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005;16:27–45. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004080648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.King AJ. The use of animal models in diabetes research. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166:877–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ilatovskaya DV, Palygin O, Levchenko V, Endres BT, Staruschenko A. The Role of Angiotensin II in Glomerular Volume Dynamics and Podocyte Calcium Handling. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:299. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00406-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominguez-Rodriguez A, et al. Urotensin-II signaling mechanism in rat coronary artery: role of STIM1 and Orai1-dependent store operated calcium influx in vasoconstriction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32:1325–1332. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.243014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodman RH, Smolik S. CBP/p300 in cell growth, transformation, and development. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1553–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hua P, Feng W, Rezonzew G, Chumley P, Jaimes EA. The transcription factor ETS-1 regulates angiotensin II-stimulated fibronectin production in mesangial cells. Am. J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F1418–F1429. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00477.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian L, et al. Role of urotensin II in advanced glycation end product-induced extracellular matrix synthesis in rat proximal tubular epithelial cells. Int J Mol Med. 2016;38:1831–1838. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzanidis A, et al. Direct actions of urotensin II on the heart: implications for cardiac fibrosis and hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2003;93:246–253. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000084382.64418.BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahn JD, et al. Transcription factor decoy for AP-1 reduces mesangial cell proliferation and extracellular matrix production in vitro and in vivo. Gene Ther. 2004;11:916–923. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawano H, et al. Differential contribution of three mitogen-activated protein kinases to PDGF-BB-induced mesangial cell proliferation and gene expression. J Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2003;14:584–592. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000050415.97942.2F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whiteside C, Munk S, Zhou X, Miralem T, Templeton DM. Chelation of intracellular calcium prevents mesangial cell proliferative responsiveness. J Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1998;9:14–25. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manna PR, Stocco DM. Crosstalk of CREB and Fos/Jun on a single cis-element: transcriptional repression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene. J Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;39:261–277. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu P, et al. Store-Operated Ca2+ Channels in Mesangial Cells Inhibit Matrix Protein Expression. J Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015;26:2691–2702. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014090853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saleh H, Schlatter E, Lang D, Pauels HG, Heidenreich S. Regulation of mesangial cell apoptosis and proliferation by intracellular Ca2+ signals. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1876–1884. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2000.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Song JH, Jung SY, Hong SB, Kim MJ, Suh CK. Effect of high glucose on basal intracellular calcium regulation in rat mesangial cell. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23:343–352. doi: 10.1159/000072916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chaudhari S, et al. High glucose and diabetes enhanced store-operated Ca2+ entry and increased expression of its signaling proteins in mesangial cells. Am. J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306:F1069–F1080. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00463.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adebiyi A, Soni H, John TA, Yang F. Lipid rafts are required for signal transduction by angiotensin II receptor type 1 in neonatal glomerular mesangial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2014;324:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Soni H, Adebiyi A. TRPC6 channel activation promotes neonatal glomerular mesangial cell apoptosis via calcineurin/NFAT and FasL/Fas signaling pathways. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29041. doi: 10.1038/srep29041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]