Abstract

Background

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a common cause of reproductive and metabolic dysfunction. We hypothesized that serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) may constitute a new biomarker for hyperandrogenism in PCOS.

Method

We conducted a cross-sectional study of 45 women with PCOS and 40 controls. Serum from these women was analyzed for androgenic steroids and for complexed PSA (cPSA) and free PSA (fPSA) with a novel fifth generation assay with a sensitivity of ~10 fg/mL for cPSA and 140 fg/mL for fPSA.

Results

cPSA and fPSA levels were about 3 times higher in PCOS compared to controls. However, in PCOS, cPSA and fPSA did not differ according to hip-to-waist ratio, Ferriman-Gallwey score, or degree of hyperandrogenemia or oligo-ovulation. In PCOS and control women, serum cPSA and fPSA levels were highly correlated with each other, and with free and total testosterone levels, but not with other hormones. Adjusting for age, body mass index (BMI) and race, cPSA was significantly associated with PCOS, with an odds ratio (OR) of 5.67 (95% CI: 1.86, 22.0). The OR of PCOS for fPSA was 7.04 (95% CI: 1.65, 40.4). A multivariate model that included age, BMI, race and cPSA yielded an area-under-the-receiver-operating-characteristic (AUC-ROC) curve of 0.89.

Conclusions

Serum complexed PSA and free PSA are novel biomarkers for hyperandrogenism in PCOS and may have value for disease diagnosis.

Keywords: Polycystic ovarian syndrome, hyperandrogenism, hirsutism, prostate specific antigen, androgen-regulated genes, serum biomarkers, urine biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

The polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) was recognized more than 80 years ago and is one of the most common causes of reproductive and metabolic dysfunction in women (1). The prevalence of this disorder globally has been generally reported to be between 5% and 15%. The diagnosis of PCOS centers on the presence of hyperandrogenism, ovulatory dysfunction and polycystic ovarian morphology (1). Patients with PCOS also have a number of comorbidities, including menstrual dysfunction, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, and increased risk for endometrial carcinoma; insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and increased risk for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, metabolic dysfunction, and possibly cerebro- and cardio-vascular disease; and psychosexual dysfunction (2).

In PCOS, hyperandrogenism can be evident clinically (e.g. hirsutism) or biochemically, including the elevation of total (TT) and free (FT) testosterone, and other androgenic steroids and metabolites in the circulation (3). Biochemical evaluation currently requires remote measurement of these specimens for most patients as the methodologies used require radioactivity or expensive mass spectrometry instrumentation not available to the standard hospital laboratory. This shipping of the specimen for analysis can delay patient diagnosis confirmation for weeks, causing delays in care and increased psychological stress to patients. In men, serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) is a well-known marker not only of prostatic carcinoma (4), but also of circulating androgens (5). Previously it was believed that PSA did not exist in any female tissue or fluid, since it is produced in men by the prostate gland, an organ women do not have. However, our group convincingly demonstrated that PSA is produced in significant amounts by many tissues in females, including breast, periurethral, salivary and thyroid tissues, and by many tumors (6, 7). We and others have also demonstrated that the PSA gene is upregulated by androgens and progestins in breast and other female tissues, as well as in model systems such as breast carcinoma cell lines (8–11).

In hirsute females and those with PCOS, serum and/or urine PSA have been reported to be elevated (12–14). Our own previous study reported urinary PSA levels almost 200 fold higher in females with PCOS in comparison to controls (12). Vural et al. reported serum PSA elevations in patients with PCOS (13), a finding confirmed by others (14–18). We have further documented that serum and urine PSA levels are highly elevated in female-to-male transsexuals after testosterone treatment, thereby demonstrating that androgens regulate PSA synthesis in female tissues in vivo (19, 20).

PSA circulates in blood as a complex with alpha 1 antichymotrypsin (complexed PSA; cPSA), which accounts for approximately 80% of total PSA, as well as in free form (free PSA or non-complexed PSA; fPSA), which accounts for the remaining 20% of total PSA (21, 22). While the original PSA assays had limits of detection of around 0.1 ng/ml for total PSA, third generation assays, developed about 20 years ago, achieve detection limits of around 1 pg/mL for total PSA (23,24). However, even with such levels of sensitivity, PSA assays could not accurately quantify cPSA or fPSA levels in the female circulation, since the levels of these fractions in females are extremely low (around 1 pg/mL, or close to the detection limit of such assays) (25). Recently, fifth-generation PSA assays with sensitivities in the 0.1 to 0.01 pg/mL range have been developed, which is enough to accurately quantify both cPSA and fPSA in the circulation of females (26–31).

In the present study we hypothesize that the measurement of cPSA and fPSA may serve as an alternative to androgen (TT and FT) measures in evaluating for biochemical hyperandrogenism in the PCOS (32).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Subject selection criteria have been reported previously (3). Some details are described below:

Serum samples from 45 women with PCOS were studied. The presence of PCOS was defined according to the NIH 1990 criteria, including: 1) clinical evidence of hyperandrogenism and/or hyperandrogenemia; 2) oligo-ovulation; and 3) exclusion of related disorders (e.g., congenital adrenal hyperplasia, thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia) as previously defined (33, 34). The degree of body and facial terminal hair growth was assessed visually by the modified Ferriman-Gallwey (mFG) score. The degree of hyperandrogenemia was assessed by the measurement of total (TT) and free testosterone (FT), androstenedione (A4), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS). Ovulatory dysfunction was defined as menstrual cycles of greater than 45 days in length or less than 8 cycles per year, or by a luteal phase (cycle day 22–24) progesterone level of less than 4 ng/mL [12.7nmol/L] if cycles were less than 45 days in length.

Serum samples from 40 healthy control women were also studied. Controls were defined as healthy non-pregnant, non-hirsute, premenopausal, eumenorrheic women without personal or family history of hirsutism and/or endocrine disorders. Controls were recruited by responding to posted advertisements.

Neither PCOS nor control subjects were taking any medications that could impact hormonal levels for at least 3 months prior to blood collection, and all underwent a history and physical examination. A fasting blood sample was obtained during the follicular phase (cycle days 3–8) of the menstrual cycle or, if oligo-amenorrheic, at days 3–8 after a withdrawal bleed was induced with oral micronized progesterone. Serum samples were kept frozen at −80 °C until thawed for analysis. All subjects were recruited either at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) or at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC); the study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for Human Protection of UAB and CSMC. Written consent was obtained from all subjects. Some of these subjects were reported previously (3).

Hormonal and chemical assays

TT and FT were measured as previously described (3, 35). In brief, TT was measured by high-turbulence liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS; Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute, San Juan Capistrano, California). In brief, TT measurement by LC-MS/MS was performed by first preanalytically processing the samples, and included acidifying, addition of internal standard, autosampling, and separation by a high-turbulence liquid chromatography column followed by passage through a C12 analytical high pressure liquid chromatography column. TT was then quantitated using a Finnigan TSQ Quantum Ultra (ThermoFisher, San Jose, CA) tandem mass spectrometer. The sensitivity of the assay (LOQ), set at a coefficient of variation (CV) of 20%, was 0.3 ng/dL [0.01nmol/L]. The CV for all reproducibility data was <15% and ranged from 7.6% to 10.8% for intra-assay and 9.8% to 13.4% for inter-assay variability.

Free testosterone was determined by equilibrium dialysis (Quest Diagnostics Nichols Institute, San Juan Capistrano, California), based on the TT measure, as previously described (3, 35). In brief, serum samples were diluted in the presence of tritiated testosterone as the tracer. The diluted sample was placed on the sample side of the dialysis chamber and the same physiological salt buffer without tracer was placed on the other (buffer) side. The tracer was allowed to reach equilibrium with the endogenous testosterone and the binding proteins. Following incubation a sample from each side of the membrane was removed, and the amount of tracer present in each was determined. The FT concentration was then calculated from the percent of tracer that crossed to the other side of the chamber and the TT concentration, as determined by the method outlined above.

Androstenedione (A4), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), and sex hormone-binding globulin were measured as previously described (34). In brief SHBG activity was measured by competitive binding, using Sephadex G-25 and [3H]T as the ligand. DHEAS and A4 were measured by direct RIA using commercially available kits (S+DHEAS from Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA; A4 from Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX). The glucose and insulin assays were performed as previously described (36). In brief, glucose assays were performed with Ektachem DT slides (Johnson & Johnson Clinical Diagnostics, Rochester, NY) and insulin was measured by RIA (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX).

Measurement of complexed and free PSA

One vial of 200μL per sample was provided blinded to Meso Scale Diagnostics (MSD) for cPSA and fPSA measurement using MSD’s MULTI-ARRAY® electrochemiluminescence technology in the S-PLEX™ format, which allows quantitation of previously unmeasurable levels of biomarkers with fg/mL sensitivity (27, 37). The samples were thawed and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C before being aliquoted into low retention 96 well round bottom plates for subsequent testing. Plates were immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until testing. cPSA and fPSA assays were calibrated to the WHO International Standard for prostate-specific antigen with 90% bound to alpha1-antichymotrypsin and 10% in the free form (National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC), code 96/670, Hertfordshire, England) and the WHO International Standard for prostate-specific antigen free (NIBSC, code 96/668), respectively. Assay characteristics were determined prior to sample testing (see below).

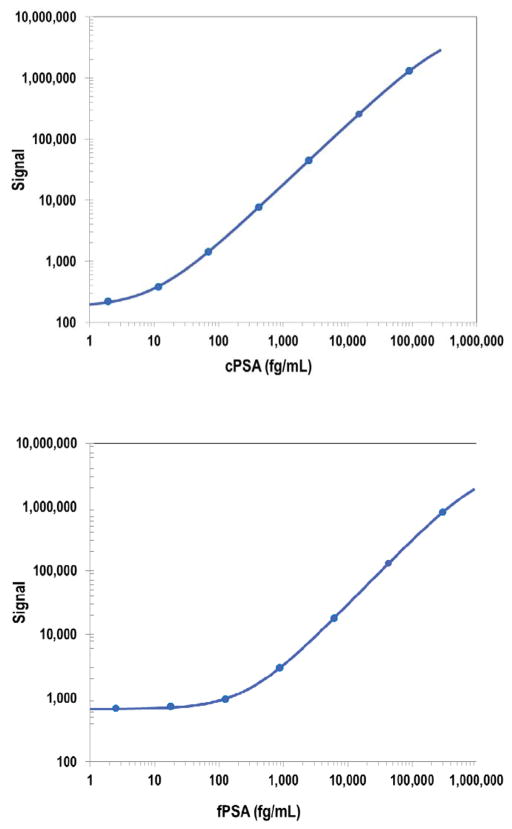

For each assay 8-point calibration curves were included on each plate (Figure 1), and the data were fitted with a weighted 4-parameter logistic curve fit. Limit of detection (LOD) is a calculated concentration corresponding to the average signal 2.5 standard deviations above the background (zero calibrator). Lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) and upper limit of quantitation (ULOQ) are established for the plate lot by measuring multiple levels of calibrator near the expected LLOQ and ULOQ. LLOQ and ULOQ are, respectively, the lowest and highest concentration of calibrator tested which have a %CV of 20% or less, with recovered concentration within 70–130%. The LOD was 5.7 and 140 fg/mL for cPSA and fPSA assays, respectively. Values of fPSA that were measured to be below the LOD (approx. 45% of the samples) were set to be equal to 70 fg/mL, or half the LOD. The LLOQ was 17 and 480 fg/mL for cPSA and fPSA assays, respectively. The ULOQ was 72,000 and 240,0000 fg/mL for cPSA and fPSA assays, respectively. Precision was determined from testing of three internal quality control samples that span the detectable range and is expressed as the %CV from 16 specimen assay runs, with 2 operators over 3 testing days. % CVs were between 11–13% for cPSA and 6–23% for fPSA.

Figure 1.

Calibration curves for cPSA and fPSA. Representative calibration curves for cPSA (upper panel) and fPSA (lower panel) are presented with weighted 4-parameter logistic curve fit. For other assay performance variables see text.

Serum, EDTA plasma, and heparin plasma samples (7–8 samples total) were spiked with calibrator at two or three concentrations. The non-complexing form of PSA (Scripps Laboratories, San Diego, CA; #90024) that does not bind to α1- antichymotrypsin (ACT) was used in spike recovery experiments for the fPSA assay. Average spike recoveries for the fPSA and cPSA assays were 88% and 90%, respectively. Serum, EDTA plasma, and heparin plasma samples (7–8 samples total) were diluted 2, 4 and 8-fold. Average dilution linearities for the fPSA and cPSA assays were 114% and 109%, respectively.

The samples and calibrator dilutions were assayed in duplicate and all samples were measured for cPSA and fPSA. Measurement of cPSA was performed with a 2 fold dilution of the samples; fPSA measurement was performed on neat samples. Concentrations of biomarkers in each sample were calculated from the calibrator curves taking into account sample dilutions. The mean of two measurements was derived for each analyte in each sample and reported in fg/mL.

Statistical analysis

We first summarized the PCOS and control samples by several clinico-pathological variables and hormonal measurements. When comparing clinical and hormonal variables among PCOS patients and controls, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine if there were significant differences in marker values. Marker correlations for PCOS samples and controls were examined using the Spearman correlation coefficients. We modeled the probability of a serum sample belonging to PCOS patients using logistic regression. Odds Ratios (ORs), receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves, and area-under-the-ROC curve (AUC-ROC) were calculated for each covariate of interest.

We then fit several different multivariate logistic models and reported age/BMI/race- adjusted ORs for cPSA and fPSA and AUC-ROC performance. We also built the best predictive model among the set of all measured covariates using LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) (38), a variable-selection method that aims to build simple models that have high predictive accuracy. Since we use the same data to both fit the model and evaluate its performance, bootstrap bias-correction was used to adjust for over-optimism (39).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Subjects

The age range of the 45 PCOS subjects was 19 to 40 years (mean ± SD: 27.9±5.26 years) and their BMI ranged from 19.5 to 55.6 kg/m2 (37.6±8.8 kg/m2); 33 were white and 12 were black or of other races. Control subjects ranged in age from 20 to 56 years (34.5±8.6 years) with BMIs ranging from 25.3 to 58.7 kg/m2 (32.74±7.28 kg/m2); 15 were white and 25 were black or of other races. The differences of PCOS and controls in terms of age, BMI and race are significant, and these parameters were modeled as adjusting variables in the multivariate analysis (see below).

Relationship of cPSA and fPSA to clinical features and PCOS phenotypes

The distribution of cPSA and fPSA among women with PCOS by waist-to-hip-ratio (WHR), dichotomized by the observed median value of 0.84 is depicted in Supplementary Figure 1. Overall, there was no association between WHR and either cPSA or fPSA. Supplementary Figure 2 depicts the cPSA and fPSA values in three PCOS phenotypes: a) those with hirsutism (i.e. mFG >6) + hyperandrogenemia + oligo-ovulation (n=20); b) those with hirsutism + oligo-ovulation only (n=8); and c) those with hyperandrogenemia + oligo-ovulation only (n=13). There is no difference in cPSA or fPSA between the three phenotypes of PCOS. Supplementary Figure 3 depicts the distributions of cPSA and fPSA in PCOS women with menstrual cycles < 3 months (n=13) and > 3 months (n=28). Again, there is no difference between these two groups of PCOS women for either cPSA or fPSA.

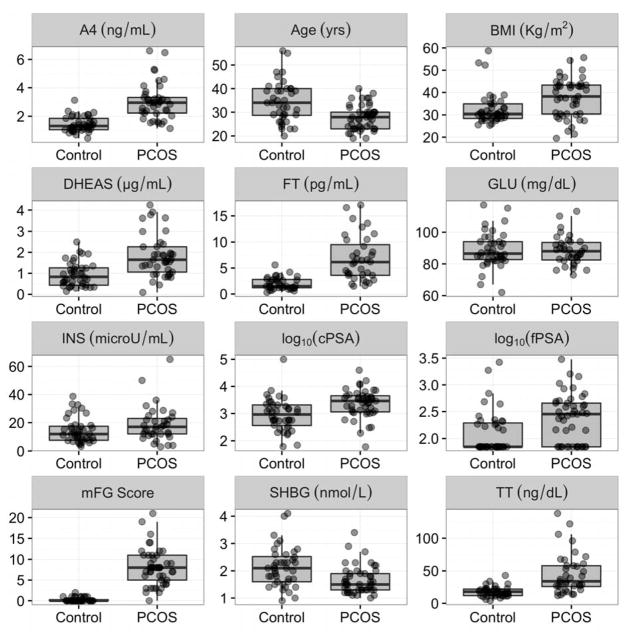

Table 1 and Figure 2 present the distributions of all clinical and biochemical parameters between the control and the PCOS cohorts. All parameters, except glucose and insulin, were significantly different between the two groups. Both cPSA and fPSA were, on average, about 3 times higher in PCOS vs. controls and these differences were highly statistically significant.

Table 1.

Distribution of variables in polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)1 and control subjects

| Controls | PCOS | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 34 (29, 40)2 | 28 (23, 30) | 0.0002 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 30 (28, 35) | 38 (30, 43) | 0.0039 |

|

| |||

| BMI (categorized) | |||

| <30 kg/m2 | 16 (62%) | 10 (38%) | 0.00023 |

| >30, <40 kg/m2 | 21 (62%) | 13 (38%) | |

| >40 kg/m2 | 3 (12%) | 22 (88%) | |

|

| |||

| Race (count (%)) | |||

| White | 15 (31%) | 33 (69%) | 0.00114 |

| Non-white | 25 (68%) | 12 (32%) | |

|

| |||

| TT (ng/dL) | 18 (12, 22) | 34 (26, 58) | < 0.00001 |

| FT (pg/mL) | 1.5 (1.2, 2.8) | 6.2 (3.6, 9.5) | < 0.00001 |

| A4 (ng/mL) | 1.31 (1.05, 1.85) | 2.94 (2.22, 3.31) | < 0.00001 |

| DHEAS (μg/mL) | 0.83 (0.44, 1.26) | 1.65 (1.06, 2.26) | 0.00002 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 210 (160, 250) | 150 (130, 190) | 0.00074 |

| GLU (mg/dL) | 86 (83, 94) | 88 (82, 94) | 0.95761 |

| INS (microU/mL) | 11.9 (7.7, 17.4) | 17 (12, 23) | 0.10409 |

| mFG score | 0 (0, 0.2) | 8 (5, 11) | < 0.00001 |

|

| |||

| cPSA (fg/mL) | 942 (360, 2070) | 2893 (1148, 4525) | 0.0005 |

| fPSA (fg/mL) | 70 (70, 194) | 284 (70, 455) | 0.0017 |

See non-standard abbreviations for full list.

Median (25th, 75th) or count (%) for covariates in PCOS and control samples.

Chi square test. Other p-values were calculated using Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Fisher’s exact test.

Figure 2.

Distributions of all examined variables between polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) samples (N=45) and control groups (N=40). For p-values see Table 1. See non-standard abbreviations for full list.

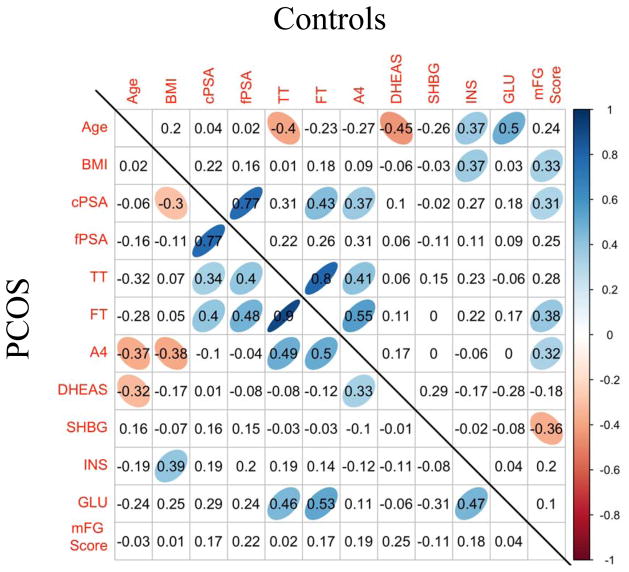

Figure 3 depicts the Spearman correlations between all continuous variables for both the PCOS and control groups. The strongest (and statistically significant) correlations of cPSA in the PCOS cohort were with fPSA, followed by FT and TT. Similarly, the strongest correlation of fPSA in PCOS was with cPSA, and then FT and TT. In control subjects, cPSA correlated strongly with fPSA, FT, A4 and the mFG score, while fPSA was not significantly correlated with any other hormones. Other significant and known correlations between various hormones and other analytes are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Spearman correlation among polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) samples (N=45) (lower diagonal) and controls (N=40) (upper diagonal). Cells with a colored ellipse indicate that the correlation is significantly different from 0 with a p-value less than 0.05. See non-standard abbreviations for full list.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis

We developed univariate models for various clinico-pathological variables and hormonal levels, calculating the ORs and constructing corresponding ROC curves. The OR for a patient with elevated cPSA having PCOS was 3.85 (95% CI 1.67, 10.0) and with elevated fPSA having PCOS was 4.74 (95% CI 1.64, 4.1) (Table 2). When OR was adjusted for age, categorical BMI and race, the OR increased to 5.67 (95% CI 1.86, 22.0) and 7.04 (95% CI 1.65, 40.4) for cPSA and fPSA, respectively, demonstrating that both cPSA and fPSA are associated with PCOS after adjustment for covariates.

Table 2.

Univariate models for clinical and biochemical variables

| Univariate OR (95% CI) | Univariate AUC-ROC (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 0.87 (0.80, 0.93) | 0.735 (0.628, 0.842) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.08 (1.02, 1.15) | 0.682 (0.563, 0.802) | |

|

| |||

| BMI (categorized) | - | ||

| <30 kg/m2 | 1 | - | |

| >30<40 kg/m2 | 0.99 (0.35, 2.87) | - | |

| >40 kg/m2 | 11.7 (3.09, 59.4) | - | |

|

| |||

| Race (count (%)) | |||

| White | 1 | - | |

| Non-white | 0.22 (0.08, 0.54) | - | |

|

| |||

| TT (ng/dL) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.21) | 0.842 (0.753, 0.931) | 1.11 (1.04, 1.22) |

| FT (pg/mL) | 2.62 (1.73, 4.65) | 0.907 (0.842, 0.971) | 3.58 (1.86, 10.1) |

| A4 (ng/mL) | 12.07 (4.77, 40.7) | 0.915 (0.856, 0.974) | 40.1 (7.15, 739) |

| DHEAS (μg/mL) | 4.65 (2.23, 11.4) | 0.775 (0.673, 0.877) | 4.29 (1.71, 14.0) |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 0.28 (0.12, 0.6) | 0.713 (0.601, 0.824) | 0.22 (0.06, 0.58) |

| GLU (mg/dL) | 1 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.496 (0.363, 0.629) | 1.02 (0.95, 1.11) |

| INS (microU/mL) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | 0.61 (0.479, 0.74) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.08) |

|

| |||

| cPSA (fg/mL) | 3.85 (1.67, 10.0) | 0.719 (0.609, 0.830) | 5.67 (1.86, 22.0) |

| fPSA (fg/mL) | 4.74 (1.64, 4.1) | 0.689 (0.579, 0.799) | 7.04 (1.65, 40.4) |

Odds ratios (ORs) are adjusted for age, categorical BMI, and race. See non-standard abbreviations for full list.

We then built multivariate models as follows: a) including age, BMI, race and fPSA, which gave a bootstrap-corrected AUC-ROC of 0.88 (CI: 0.82–0.94); and b) including age, BMI, race and cPSA, which gave a bootstrap-corrected AUC-ROC of 0.89 (CI: 0.83–0.95). These models, along with their adjusted ORs demonstrate that cPSA and fPSA are both significantly associated with PCOS status, after adjusting for age, BMI and race, and have discriminatory capacity beyond these three adjusting variables, which have a combined AUC-ROC of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.79–0.93).

We used a method called LASSO (38) to build the most predictive multivariate model among the set of covariates shown in Table 2. The model selected age, categorical BMI, race, FT, A4, DHEAS, and SHBG and achieved an AUC of 0.97 (0.94, 0.98). A model that excluded FT and included fPSA gave identical performance. Finally, a model that replaced FT with A4 (i.e. included only age, categorical BMI, race, A4, DHEAS and SHBG) gave an AUC only slightly lower at 0.96 (0.95, 0.98).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have focused on the diagnostic value of PSA in women with PCOS and other hyperandrogenic states (12–18). However, none of these studies had the ability to accurately quantify either total PSA or PSA subfractions in female serum due to their very low concentrations (<1pg/mL) (25). Recently developed fifth generation assays can quantify PSA at extremely low levels, around 10 to 100 fg/mL (26–31, 37), sufficient to quantify both complexed PSA and free PSA in female serum. In the present study, for the first time we report that the average concentration of complexed PSA in serum of normal women is approx. 942 fg/mL, while the concentration of fPSA is about ten times lower, at around 70 fg/mL. The ratio of cPSA/fPSA in males is similar, but their serum PSA is approx. 1000-fold higher. Previously it has been documented that complexed PSA represents enzymatically active PSA bound to the proteinase inhibitor alpha-1-antichymotrypsin, while free PSA represents a mixture of inactive forms of PSA such as pro PSA and internally clipped PSA (21, 22, 40).

Our hypothesis that serum PSA in females may be a novel biomarker of hyperandrogenism is based on the fact that the PSA gene is up-regulated by androgens, through the action of androgens on the androgen receptor (8–11). Previous studies have documented the presence of active androgen response elements within the PSA gene promoter and enhancer regions (41–43). We hypothesized that in women with hyperandrogenism, whether clinically obvious or not, the PSA gene is unregulated, thus leading to increased PSA protein in female circulation. Our data supports this hypothesis, demonstrating that both cPSA and fPSA are, on average, approximately 3-fold higher in women with PCOS than in control women. The involvement of androgens in the upregulation of the PSA gene in these women is further suggested by the significant correlations between both cPSA and fPSA with FT and TT levels in both PCOS and control women. Indeed, it seems plausible that the increased levels of both cPSA and fPSA in the female circulation of PCOS patients is driven by testosterone, as it has been shown in in vitro systems such as breast carcinoma cell lines (8). In vivo, PSA is increased in both serum and urine after the administration of testosterone to young female-to-male transsexuals (19, 20). Although we did not characterize the tissue source of PSA in this study, we have previously demonstrated that the major site of production of PSA in female tissues is the breast, and that PSA could be upregulated in this tissue by steroid hormones (11).

We have previously observed very significant elevations in urinary PSA in women with hyperandrogenism (12). However, we do not favor this fluid for diagnostic purposes since there is a significant chance of contamination of urine by seminal PSA during sexual intercourse. However, if urinary contamination by seminal fluid could be excluded, then, urinary PSA could be an even more sensitive marker of hyperandrogenism in women (12).

ROC curve analysis of the various biochemical parameters measured in this study demonstrated that although all hormonal and PSA measurements are good biomarkers, the largest area under the curve was displayed by A4 and FT, followed by TT. We developed multivariate models which included age, BMI, race and fPSA or cPSA and the AUC-ROC increased to 0.89. The most predictive multivariate model included age, categorical BMI, race, FT, A4, DHEAS, and SHBG and achieved an AUC-ROC of 0.97. However, replacing FT for fPSA in this model yielded an identical predictive value.

We conclude that cPSA and fPSA can now be measured reliably in female serum with fifth generation assays and that they are novel biomarkers for hyperandrogenism in women in PCOS. These new measures (cPSA, fPSA) may be useful, either alone or in combination with other existing markers, for better disease diagnosis in women with suspected PCOS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by the Partnership for Clean Competition.

Non-standard abbreviations

- PCOS

polycystic ovarian syndrome

- PSA

prostate specific antigen

- cPSA

complexed PSA

- fPSA

free PSA

- WHR

waist-to-hip ratio

- FG

Ferriman-Gallwey

- ACTH

adrenocorticotropin

- BMI

body mass index

- TT

total testosterone

- FT

free testosterone

- A4

Androstenedione

- DHEAS

dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- SHBG

sex hormone binding globulin

- GLU

glucose

- INS

insulin

- LC/MS/MS

liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- AUC

area under the curve

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

95% confidence interval

- LOD

limit of detection

- LLOQ

lower limit of quantification

- ULOQ

upper limit of quantification

- ACT

a1- antichymotrypsin

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: RA is on the advisory board of Global PET and a consultant to KinDex Pharmaceuticals; SH, AM, MS, GN AND ENG are employees of Meso Scale; the remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions: EPD conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript with help from all the co-authors. FZS participated in patient selection. SW, AM, MS, EG, and GN participated in PSA sample analysis. MDB and YZ performed the statistical analysis and YHC, HW and RA participated in patient selection.

References

- 1.Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, Diamanti-Kandarakis E, et al. Task Force on the Phenotype of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome of The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:456–88. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peigné M, Dewailly D. Long term complications of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2014;75:194–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2014.07.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salameh WA, Redor-Goldman MM, Clarke NJ, Mathur R, et al. Specificity and predictive value of circulating testosterone assessed by tandem mass spectrometry for the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome by the National Institutes of Health 1990 criteria. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1135–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diamandis EP. Prostate-specific antigen: its usefulness in clinical medicine. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1998;9:310–6. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(98)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porcaro AB, Caruso B, Terrin A, De Luyk N, et al. The preoperative serum ratio of total prostate specific antigen (PSA) to free testosterone (FT), PSA/FT index ratio, and prostate cancer. Results in 220 patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2016;88:17–22. doi: 10.4081/aiua.2016.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diamandis EP, Yu H. Nonprostatic sources of prostate-specific antigen. Urol Clin North Am. 1997;24:275–82. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70373-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black MH, Diamandis EP. The diagnostic and prognostic utility of prostate-specific antigen for diseases of the breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;59:1–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1006380306781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu H, Diamandis EP, Zarghami N, Grass L. Induction of prostate specific antigen production by steroids and tamoxifen in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;32:291–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00666006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleutjens KB, van der Korput HA, van Eekelen CC, van Rooij HC, Faber PW, Trapman J. An androgen response element in a far upstream enhancer region is essential for high, androgen-regulated activity of the prostate-specific antigen promoter. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:148–61. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.2.9883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleutjens KB, van Eekelen CC, van der Korput HA, Brinkmann AO, Trapman J. Two androgen response regions cooperate in steroid hormone regulated activity of the prostate-specific antigen promoter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6379–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu H, Diamandis EP, Monne M, Croce CM. Oral contraceptive-induced expression of prostate-specific antigen in the female breast. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6615–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obiezu CV, Scorilas A, Magklara A, Thornton MH, Wang CY, Stanczyk FZ, et al. Prostate-specific antigen and human glandular kallikrein 2 are markedly elevated in urine of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1558–61. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vural B, Ozkan S, Bodur H. Is prostate-specific antigen a potential new marker of androgen excess in polycystic ovary syndrome? J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2007;33:166–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahceci M, Bilge M, Tuzcu A, Tuzcu S, Bahceci S. Serum prostate specific antigen levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and the effect of flutamide+desogestrel/ethinyl estradiol combination. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004;27:353–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03351061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kocak M, Tarcan A, Beydilli G, Koç S, Haberal A. Serum levels of prostate-specific antigen and androgens after nasal administration of a gonadotropin releasing hormone-agonist in hirsute women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2004;18:179–85. doi: 10.1080/09513590410001692465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burelli A, Cionini R, Rinaldi E, Benelli E, et al. Serum PSA levels are not affected by the menstrual cycle or the menopause, but are increased in subjects with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29:308–12. doi: 10.1007/BF03344101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mardanian F, Heidari N. Diagnostic value of prostate-specific antigen in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:999–1005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bili E, Dampala K, Iakovou I, Tsolakidis D, et al. The combination of ovarian volume and outline has better diagnostic accuracy than prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentrations in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOs) Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;179:32–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obiezu CV, Giltay EJ, Magklara A, Scorilas A, Gooren LJ, Yu H, et al. Serum and urinary prostate-specific antigen and urinary human glandular kallikrein concentrations are significantly increased after testosterone administration in female-to-male transsexuals. Clin Chem. 2000;46:859–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slagter MH, Scorilas A, Gooren LJ, de Ronde W, Soosaipillai A, Giltay EJ, et al. Effect of testosterone administration on serum and urine kallikrein concentrations in female-to-male transsexuals. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1546–51. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.067041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stenman UH, Leinonen J, Alfthan H, Rannikko S, et al. A complex between prostate-specific antigen and alpha 1-antichymotrypsin is the major form of prostate-specificantigen in serum of patients with prostatic cancer: assay of the complex improves clinical sensitivity for cancer. Cancer Res. 1991;51:222–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lilja H, Christensson A, Dahlén U, Matikainen MT, et al. Prostate-specific antigen in serum occurs predominantly in complex with alpha 1-antichymotrypsin. Clin Chem. 1991;37:1618–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu H, Diamandis EP, Wong PY, Nam R, Trachtenberg J. Detection of prostate cancer relapse with prostate specific antigen monitoring at levels of 0.001 to 0.1 microG./L. J Urol. 1997;157:913–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferguson RA, Yu H, Kalyvas M, Zammit S, Diamandis EP. Ultrasensitive detection of prostate-specific antigen by a time-resolved immunofluorometric assay and the Immulite immunochemiluminescent third-generation assay: potential applications in prostate and breast cancers. Clin Chem. 1996;42:675–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giai M, Yu H, Roagna R, Ponzone R, Katsaros D, Levesque MA, et al. Prostate-specific antigen in serum of women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;72:728–31. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang J, Yao C, Li X, Wu Z, Huang C, Fu Q, et al. Silver nanoprism etching-based plasmonic ELISA for the high sensitive detection of prostate-specific antigen. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;69:128–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikolenko GN, Stengelin MK, Sardesai L, Glezer EN, Wohlstadter JN. Abstract 2012: Accurate measurement of free and complexed PSA concentrations in serum of women using a novel technology with fg/mL sensitivity [abstract]. Cancer Res; Proceedings of the 106th Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research; 2015 Apr 18–22; Philadelphia, PA. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thaxton CS, Elghanian R, Thomas AD, Stoeva SI, Lee JS, Smith ND, et al. Nanoparticle-based bio-barcode assay redefines “undetectable” PSA and biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:18437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904719106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDermed JE, Sanders R, Fait S, Klem RE, Sarno MJ, Adams TH, et al. Nucleic acid detection immunoassay for prostate-specific antigen based on immuno-PCR methodology. Clin Chem. 2012;58:732–40. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.170290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson DH, Hanlon DW, Provuncher GK, Chang L, Song L, Patel PP, et al. Fifth-generation digital immunoassay for prostate-specific antigen by single molecule array technology. Clin Chem. 2011;57:1712–21. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.169540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rissin DM, Kan CW, Campbell TG, Howes SC, Fournier DR, Song L, et al. Single-molecule enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detects serum proteins at subfemtomolar concentrations. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:595–9. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosner W, Auchus RJ, Azziz R, Sluss PM, Raff H. Position statement: Utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:405–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zawadzki JK, Dunaif A. In: Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: towards a rational approach. Dunaif A, GJHFMGe, editors. Boston: Blackwell Scientidic; 1992. pp. 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knochenhauer ES, Key TJ, Kahsar-Miller M, Waggoner W, et al. Prevalence of the polycystic ovary syndrome in unselected black and white women of the southeastern United States: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3078–82. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salameh WA, Redor-Goldman NM, Clarke NJ, Reitz RE, Caulfield MP. Validation of total testosterone assay using high-turbulence liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: total and free testosterone reference ranges. Steroids. 2010;75:169–75. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeUgarte CM, Bartolucci AA, Azziz R. Prevalence of insulin resistance in the polycystic ovary syndrome using the homeostasis model assessment. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:1454–60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glezer EN, Stengelin M, Aghvanyan A, Nikolenko GN, et al. Abstract 2014: Cytokine immunoassays with sub-fg/mL detection limits. Abstract T2065. AAPS Annual Meeting; 2014; ( http://abstracts.aapps.org/published/) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tibshirani RJ. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J Royal Statist Soc B. 1996;58(1):267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the bootstrap. CRC press; 1994. Estimates of bias. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rittenhouse HG, Finlay JA, Mikolajczyk SD, Partin AW. Human kallikrein 2 (hK2) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA): two closely related, but distinct, kallikreins in the prostate. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1998;35:275–368. doi: 10.1080/10408369891234219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cleutjens KB, van der Korput HA, Ehren-van Eekelen CC, Sikes RA, Fasciana C, Chung LW, et al. A 6-kb promoter fragment mimics in transgenic mice the prostate-specific and androgen-regulated expression of the endogenous prostate-specific antigen gene in humans. Mol Endrocrinol. 1997;11:1256–65. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.9.9974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Zhang S, Murtha PS, Zhu W, Hou SS, Young CY. Identification of two novel cis-elements in the promoter of the prostate-specific antigen gene that are required to enhance androgen receptor-mediated transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3143–50. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.15.3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schuur ER, Henderson GA, Kmetec LA, Miller JD, Lamparski HG, Henderson DR. Prostate-specific antigen expression is regulated by an upstream enhancer. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7043–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.