Highlights

-

•

Role of splenectomy in MF.

-

•

Kept in mind possible presence of peritoneal implants of extramedullary hematopoiesis.

-

•

Pathogenesis of ascites formation in MF.

Keywords: Myelofibrosis, Splenomegaly, Splenectomy, Extramedullary hematopoiesis

Abstract

Introduction

Primary myelofibrosis (MF) is a myeloproliferative neoplasm that results in debilitating constitutional symptoms, splenomegaly, and cytopenias. In patients with symptomatic splenomegaly, splenectomy remains a viable treatment option for MF patients with medically refractory symptomatic splenomegaly that precludes the use of ruxolitinib.

Case presentation

We present the clinical case of a patient who was admitted to our Department to perform a splenectomy in MF as a therapeutic step prior to an allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT). A laparotomic splenectomy and excision of whitish wide-spread peritoneal and omental nodulations was performed. There were no operative complications and the surgery was completed with minimal blood loss. The histopathological exam revealed an extramedullary hematopoiesis in both spleen and peritoneal nodules.

Conclusion

In primary myelofibrosis it must always be kept in mind the possible presence of peritoneal implants of extramedullary hematopoiesis and ascites of reactive genesis. We report a rare case of peritoneal carcinomatosis-like implants of extramedullary hematopoiesis found at splenectomy for MF.

1. Introduction

Myelofibrosis (MF) is a hematopoietic stem cell disorder in the spectrum of myeloproliferative disorder that presents either as a primary disease or evolves secondarily from polycythemia vera (PV) or essential thrombocythemia (ET). MF is characterized by bone marrow fibrosis, cytopenias, abnormal cytokine expression, extramedullary hematopoiesis, systemic symptoms, anemia, splenomegaly and evolution to acute myeloid leukemia [1]. Besides medical therapies, the only curative option for patients with MF is allogeneic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) which is associated with high morbidity and mortality risks [2].

At present, splenectomy is indicated for MF patients with therapy-limiting thrombocytopenia and anemia and those with splenomegaly no longer responsive to Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor therapies and it remains a safe and effective therapy for those patients with a presplenectomy platelet count of ≥ 20 × 109/L [3].

Extramedullary hematopoiesis occurs if the bone marrow is no longer functional. It is a compensatory phenomen that results in the production of blood cell precursors outside the marrow in patients with thalessemia, myelofibrosis and in other anemic conditions.

Extramedullary hematopoiesis mimicking acute appendicitis and intestinal obstruction, rectal stenosis, gastric outlet obstruction and bladder outlet obstruction due to extramedullary hematopoiesis have been reported [4], [5], [6].

We report a rare case of peritoneal carcinomatosis-like implants of extramedullary hematopoiesis found at splenectomy for MF.

2. Case presentation

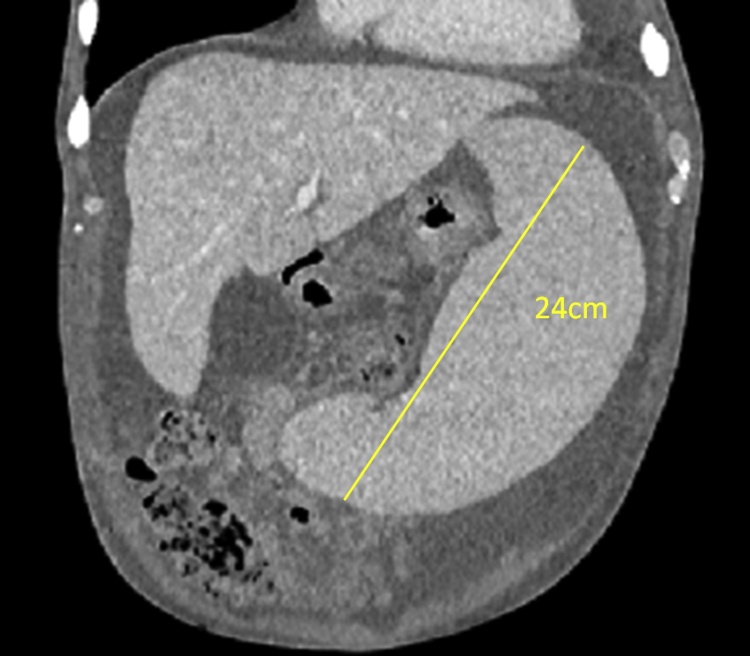

In June 2016, a 53 year-old man was admitted to our department to perform a planned splenectomy in idiopathic MF prior to ASCT. The patient had a significant past medical history of dilated cardiomyopathy diagnosed in 2014 after a severe episode of dyspnea with a residual left ventricular ejection fraction of 27%. New York Heart Association (NYHA) score was 3. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score was 3–4. ET was diagnosed about 25 years ago, confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy and treated with oncocarbide for 5 years. ET quicky evolved into idiopathic myelofibrosis coexisting with anemia which required weekly red blood cell transfusions. At the time of admission, abdominal examination showed a palpable spleen reaching the left iliac fossa and ascites. Declivous edemas were present as well. Laboratory tests revealed anemia (Hemoglobin: 9.8 g/dl); other routine exams including platelets, biochemical investigations and sierological viral markers were normal. Imaging evaluation including abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan showed significant splenomegaly (diameters: 24 × 15 × 11 cm) and widespread and abundant ascites (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

CT SCAN: splenomegaly (24 cm of maximum diameter) and abundant ascites.

A doppler flowmetry showed a slightly ectasic portal vein with a normal flow rate; no signs of thrombosis were evident.

Ascites, referred as cardiogenic, was treated with cycles of Levosimendan and diuretics with an improving of the residual ejection fraction from 27 to 35–40%.

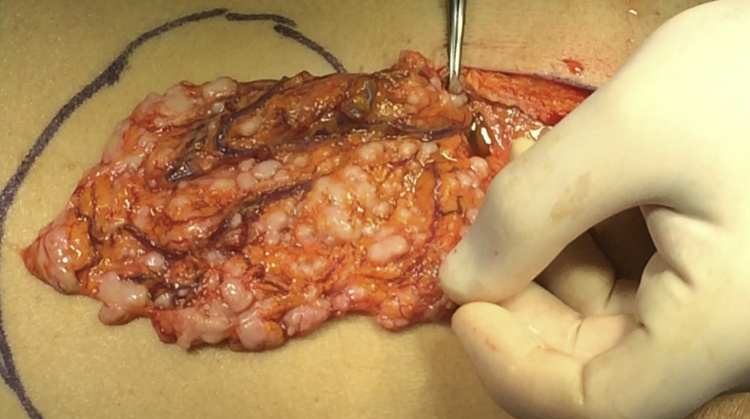

The surgical procedure was performed with a laparotomic approach through an upper midline incision. Abdominal exploration found 2500cc of ascites and whitish widespread peritoneal and omental nodulations of less than one centimeter of size (Fig. 2). Splenomegaly had extended downwards to the left iliac fossa dislocating the pancreas. The splenic vein and artery were both coarsely ectasic. Ascites was withdrawn for a physical-chemical examination and the nodules sent for histological examination.

Fig. 2.

INTRAOPERATIVE VIEW: omental nodulations.

Since the appearance of the nodulations was similar to carcinomatosis nodules, a careful exploration of the entire peritoneal cavity was made which proved to be negative.

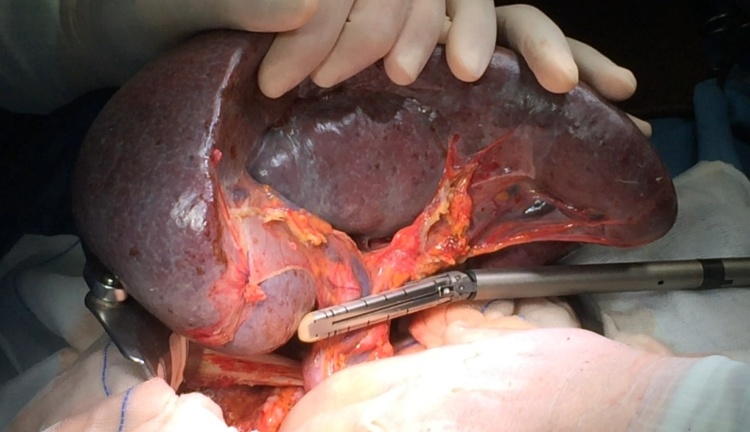

Splenectomy was performed after early splenic artery ligation to decrease the splenic volume as a first step of the procedure. After complete mobilization of the spleen with the aid of a radiofrequency device, the hilar vessels were divided with a vascular stapler, according to a technique elsewhere described [6] (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

INTRAOPERATIVE VIEW: Section of the splenic pedicle with a vascular stapler.

The operating time was 120 min and the estimated blood loss was 50 ml.

The postoperative course was normal. The patient was discharged on third post-operative day in overall good conditions. Upon pathological examination, spleen and peritoneal nodulations were determined to be extramedullary hematopoiesis foci in the context of MF.

The physical-chemical examination of ascites showed the exudative nature of the peritoneal collection, confirming the reactive genesis of the same.

The patient is alive and in healthy condition 6 months after the operation and 4 months after ASCT.

3. Discussion

MF is a myeloproliferative neoplasm that presents either as a primary disease or evolves secondarily from PV or ET, like in our case. In fact, ET was diagnosed about 25 years ago and treated with oncocarbide for 5 years. After a few years it evolved into idiopathic myelofibrosis. In such a pathology, splenectomy remains an effective and safe therapy for those with continued spleen-related mechanical symptoms refractory to JAK 1 and 2 inhibitor and for patients with severe cytopenias precluding ruxolitinib use [2].

In this case a severe anemia and a massive splenomegaly were present and the patient became transfusion dependent. Unfortunately, a treatment with JAK inhibitors reduced the splenic size but failed in relieving anemia. Therefore an indication to splenectomy was posed even if some concerns about the high operative risk due to cardiac comorbidities was present. In fact, the massive ascites showed at the preoperative CT scan had been interpreted as of cardiogenic origin. This hypothesis was supported by heart function tests, radiological and clinical findings such as moderate hepatomegaly and peripheral edema.

Ascites occurs in 2–10% of MF [8].

The pathogenesis of ascites formation in MF is essentially twofold: one is due to implants of myeloproliferative foci on the peritoneum with exudative ascites formation, and the other is due to portal hypertension [9]. In this latter case it should be distinguished a hypertension due to splenic hyperflow caused by splenomegaly, from a prehepatic obstruction as in the case of portal thrombosis or an intrahepatic obstruction due to hematopoiesis foci located in the liver [8], [10]. In our case, no arguments in favor of a portal hypertension were present, since portal flow resulted in the normal range and no images related to varices or portal thrombosis were detected at CT scan. In addition, despite a mild hepatomegaly, hepatic enzymes were normal and therefore the hypothesis of intrahepatic localization of hematopoiesis foci was a remote possibility.

As indicated above, ascites can be reactive to extramedullary hematopoiesis outbreaks whose implants may be located on the parietal and visceral peritoneum and on the greater omentum. This occurrence is known but very rare [11].

In literature, 2 forms of implants are described: a microscopic one, evident only at pathological examination, and a macro-infiltrative one. The latter gives rise to mostly singular implants that growing on visceral peritoneum can cause bowel stenosis or occlusion [4].

At preoperative CT scan, only the latter form can be seen as a pseudo tumor whose differential diagnosis has to be made among peritoneal tuberculosis, visceral tumors and nodules of extramedullary hematopoiesis [5], [7], [11], [12], [13].

In our case, no intra-abdominal nodules were reported at CT scan, although the presence of micro-infiltration could not be ruled out.

At laparotomy, the appearance of the peritoneal nodules alarmed us because of their similarity to carcinomatosis nodules as the spread of a primary tumor, however, not known. Though CT scan was negative for other tumoral lesions, we proceeded to a careful exploration of the entire peritoneal cavity which proved to be negative. The presence of such carcinomatosis-like nodules associated to MF was never been described to date. In the micro-infiltrative form, diagnosis has always been made through cell research at paracentesis, by percutaneous biopsy or at autopsy. Only in one case of a macro-infiltrative form, the patient was operated on but the diagnosis was suspected preoperatively because of a stenosing mass in the colon.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, our case was a rare case of extramedullary hematopoiesis in MF. No evidence of this finding was suspected preoperatively because serious patient's cardiac comorbidities have misled the correct pathogenesis of ascites. Facing a splenomegaly and massive ascites associated with MF, it must always be kept in mind all the pathogenetical hypotheses of ascites and thus the possible reactive genesis of implants of extramedullary hematopoiesis. Also among the macro-infiltrative forms of these implants there is also the possibility of a carcinomatosis-like shape, not known up to now.

The present work has been reported according to the SCARE criteria [14]

Author contribution

Marco Casaccia, ideated the study and drafted the article.

Rosario Fornaro, substantial contributions to conception and design.

Marco Frascio, revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Denise Palombo, acquisition of data and drafted the article.

Cesare Stabilini, revising it critically for important intellectual content.

Emma Firpo, acquisition of data.

Ezio Gianetta, final approval of the version to be submitted.

All authors approved the final draft.

Sources of funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare

Ethical approval

The paper is not a research study.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report.

Guarantor

Dr. Denise Palombo, UOC Clinica Chirurgica2, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria san Martino-IST, Monoblocco XI piano. Largo Rosanna Benzi, 10, 16132, Genova, Italy.

References

- 1.Tefferi A. Primary myelofibrosis: 2013 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 2013;88:141–150. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jain T., Mesa R.A., Palmer J.M., Lestang E., Peterlin P., Le Bris Y., Dubruille V., Delaunay J., Godon C. Is allogeneic stem cell transplantation for myelofibrosis still indicated at the time of molecular markers and JAK inhibitors era. Eur. J. Haematol. 2017;99:60–69. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aruch D., Schwartz M., Mascarenhas J., Kremyanskaya M., Newsom C., Hoffman R. Continued role of splenectomy in the management of patients with myelofibrosis. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16:e133–e137. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei X.Q., Zheng Z.H., Jin Y., Tao J., Abassa K.K., Wen Z.F. Intestinal obstruction caused by extramedullary hematopoiesis and ascites in primary myelofibrosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11921–11926. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holden C., Hennessy O., Lee W.K. Diffuse mesenteric extramedullary hematopoiesis with ascites: sonography, CT, and MRI findings. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006;186:507–509. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sunderland K., Barratt J., Pidcock M. Extramedullary hemopoiesis arising in the gut mimicking carcinoma of the cecum. Pathology. 1994;26:62–64. doi: 10.1080/00313029400169151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casaccia M., Torelli P., Cavaliere D., Santori G., Panaro F., Valente U. Minimal-access splenectomy: aviable alternative to laparoscopic splenectomy in massive splenomegaly. JSLS. 2005;9:411–414. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yotsumoto M., Ishida F., Ito T., Ueno M., Kitano K., Kiyosawa K. Idiopathic myelofibrosis with refractory massive ascites. Intern. Med. 2003;42:525–528. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel N.M., Kurtides E.S. Ascites in agnogenic myeloid metaplasia: association with peritoneal implant of myeloid tissue and therapy. Cancer. 1982;50:1189–1190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820915)50:6<1189::aid-cncr2820500627>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abu-Hilal M., Tawaker J. Portal hypertension secondary to myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia: a study of 13 cases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3128–3133. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinde S.V., Shenoy A.S., Balsarkar D.J., Shah V.B. Omental sclerosing extramedullary hematopoietic tumors in Janus kinase-2 negative myelofibrosis: caveat at frozen section. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2014;57:480–482. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.138785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzankov A., Krugmann J., Steurer M., Dirnhofer S. Idiopathic myelofibrosis with nodal, serosal and parenchymatous infiltration: case report and review of the literature. Acta Haematol. 2002;107:173–176. doi: 10.1159/000057636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elpek G.O., Bozova S., Erdoğan G., Temizkan K., Oğüs R.A. Extramedullary hematopoiesis mimicking acute appendicitis: a rare complication of idiopathic myelofibrosis. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:258–261. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agha, Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]