Abstract

Background & Aims

Surveillance guidelines for serrated polyps (SPs) are based on limited data on longitudinal outcomes of patients. We used the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry to evaluate risk of clinically important metachronous lesions associated with SPs, detected during index colonoscopies.

Methods

We collected data from a population-based colonoscopy registry that has been collecting and analyzing data on colonoscopies across the state of New Hampshire since 2004, including rates of adenoma and serrated polyp detection. Patients completed a questionnaire to determine demographic characteristics, health history, and risk factors for CRC, and were followed from index colonoscopy through all subsequent surveillance colonoscopies. Our analyses included 5433 participants (median age 61 years; 49.7% male) with 2 colonoscopies (median time to surveillance, 4.9 years). We used multivariable logistic regression models to assess effects of index serrated polyps (SP, n=1016), high-risk adenomas (HRA, n=817), low-risk adenomas (n=1418), and no adenomas (n=3198) on subsequent HRA or large SPs (>1 cm) on surveillance colonoscopy (metachronous lesions). Synchronous SPs, within each index risk group, were assessed for size and by histology. Serrated polyps comprise hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps), and traditional serrated adenomas. In this study, SSA/Ps and traditional serrated adenomas are referred to collectively as STSAs.

Results

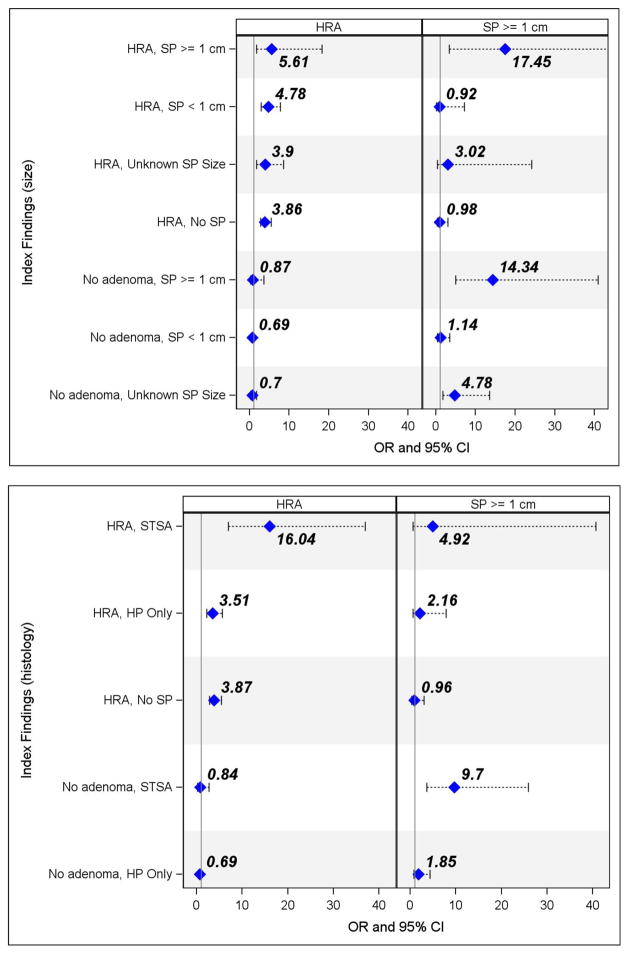

HRA and synchronous large SP (odds ratio [OR], 5.61; 95% CI, 1.72–18.28), HRA with synchronous STSA (OR, 16.04; 95% CI, 6.95–37.00), and HRA alone (OR, 3.86; 95% CI, 2.77–5.39) at index colonoscopy significantly increased the risk of metachronous HRA compared to the reference group (no index adenomas or serrated polyps). Large index SPs alone (OR=14.34; 95% CI, 5.03–40.86) or index STSA alone (OR, 9.70; 95% CI, 3.63–25.92) significantly increased the risk of a large metachronous SP.

Conclusions

In an analysis of data from a population-based colonoscopy registry, we found index large SP or index STSA with no index HRA increased risk of metachronous large SPs but not metachronous HRA. HRA and synchronous SPs at index colonoscopy significantly increased risk of metachronous HRA. Individuals with HRA and synchronous could therefore benefit from close surveillance.

Keywords: NHCR, colon cancer, early detection, risk factors

Introduction

Serrated polyps (SP) are precursor lesions for a significant proportion1 of all CRC and are therefore an important focus of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening and surveillance. Serrated polyps are detected in 9% to 21% of individuals presenting for colonoscopy2–5 and the management and timing of surveillance colonoscopy in individuals with serrated polyps is an important component of CRC prevention.

Morphologically, serrated polyps are a heterogeneous group. Based on the World Health Organization’s criteria, serrated polyps are classified as follows: hyperplastic polyp (HP), traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) and sessile serrated adenomas/polyp (SSA/P) with or without dysplasia1, 6–8. HPs, especially those that are small and distal, are believed to have minimal risk of malignant transformation1. However, SSA/P and TSA are accepted precursors of CRC and are collectively referred to as sessile and traditional serrated adenoma (STSA) throughout this manuscript. Unfortunately, SSA/Ps can be histologically difficult to distinguish from HPs9, 10 and this overlap has hampered efforts to develop evidence-based surveillance guidelines for individuals with serrated polyps.11,12

The U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer (USMSTF) has published recommendations for the surveillance of serrated polyps11. The authors state that any serrated polyps larger than 1 cm (potentially including HPs) may be clinically significant, but specific surveillance interval recommendations are provided for histologically confirmed SSA/P and TSA only. An expert panel has also published surveillance recommendations using other factors such as size of SPs, rather than relying on specific histologic diagnosis of HP or SSA/P1. The evidence supporting the recommendations of both the USMSTF and the expert panel is not entirely consistent, as stated by the authors of both publications. We therefore classified index serrated polyps by size into three categories (< 1 cm, ≥ 1 cm, and unknown) and by histology into two categories (HP and STSA).

Since CRC is an infrequent outcome among patients receiving screening or surveillance colonoscopy, CRC surveillance guidelines are based, in part, on metachronous risk of high risk adenoma (HRA), as a surrogate marker for future risk of CRC. Thus, data is needed regarding future HRA risk in individuals with index serrated polyps. Despite the large numbers of individuals with serrated polyps, there is a relative paucity of individuals with serrated lesions that may be clinically important such as SSA/Ps, TSAs or large HPs. Another challenge that can complicate efforts to examine the risk for metachronous lesions in individuals with SSA/Ps, TSAs or large HPs is the high frequency of synchronous conventional adenomas including HRA13–17. This makes it difficult to determine whether the risk for metachronous HRA arises from the serrated lesions or from the synchronous HRA, or whether the presence of synchronous serrated index polyps increases the risk as compared to HRA alone. Another salient question is whether any increased risk is due to the size or the histology of the serrated polyps. This interaction is further complicated by the fact that pathologists often take serrated polyp size and location into consideration while deciding between a diagnosis of HP or SSA/P. Longitudinal data for a large cohort of individuals with both index and surveillance colonoscopies is clearly needed to address the risk of metachronous HRA in individuals with serrated polyps.

The New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry (NHCR) is a population-based colonoscopy registry that has been collecting and analyzing data on colonoscopies across the state of New Hampshire since 2004. It collects data on all key colonoscopy quality measures, including adenoma detection rate and serrated polyp detection rate. Consenting patients are followed from index colonoscopy through all subsequent surveillance colonoscopies. In this analysis, we used longitudinal data from the NHCR to assess the risk of a HRA or a serrated polyp ≥ 1 cm on the patient’s surveillance colonoscopy (metachronous findings), based on findings from the patient’s index colonoscopy.

Methods

Consenting participants complete a self-administered NHCR patient questionnaire prior to colonoscopy, including demographic characteristics, health history, and known risk factors for CRC. The NHCR procedure form is completed during or immediately following colonoscopy by endoscopists or endoscopy nurses. The form records the indication for the colonoscopy, findings (location, size and specific treatment of polyps, cancer, or other findings), type and quality of bowel preparation, sedation medication, anatomical landmark reached during the procedure, withdrawal time, follow-up recommendations, and immediate complications. The NHCR requests pathology reports for all colonoscopies with tissue biopsies or excisions directly from the pathology laboratory used by each participating facility. Trained NHCR staff abstract and enter these pathology reports, including location, size, and histology of each polyp, into the NHCR database, linking polyp level pathology data to information from the colonoscopy procedure form. 18–20 All data collection and study procedures were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College, as well as by other relevant human subjects reviewing bodies at participating sites.

After matching colonoscopy and pathology data using the algorithm developed and described in our prior publication20, each lesion described on colonoscopy is assigned a single diagnosis. When multiple polyps are submitted in the same container, the same diagnosis is assigned to all polyps if there is only one pathologic diagnosis for all specimens. For example, if 3 polyps are submitted in a single container and the pathology diagnosis only mentions 'fragments of hyperplastic polyp' we assume a single diagnosis of HP for all 3 polyps. In the current study, most polyp diagnoses were a perfect match without the need for making assumptions as described above.

Cohort

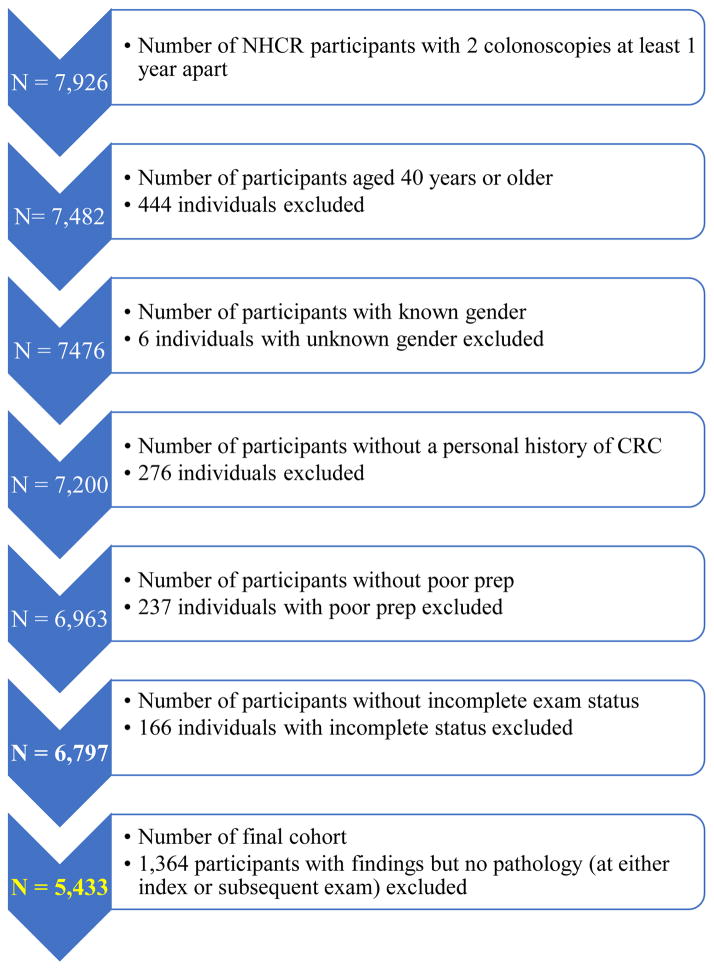

Between January, 2004, and June, 2015, we identified 7,926 NHCR patients with 2 colonoscopies that were at least 12 months apart. Individuals < 40 years (N=444), those with a personal history of CRC (N=276) and with missing gender information (N=6) were removed. Participants with poor quality bowel preparation (N =237) or an incomplete index or surveillance colonoscopy (cecum or terminal ileum was not reached or colonoscopy was aborted; N = 166) were excluded, as were 1,364 participants for whom pathology reports were missing at either index or surveillance colonoscopy. This left a final cohort of 5,433 participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cohort diagram

Definitions

We referred to the first of the participant’s 2 colonoscopies in the NHCR as their index colonoscopy. Our outcomes were metachronous HRA and large serrated polyps (≥ 1 cm), which we defined as findings on the surveillance colonoscopy, performed at least 12 months after the index examination. Since time intervals are not uniformly defined in the literature, we chose a 12 month interval to define surveillance based on previous studies examining both serrated polyps and conventional adenomas21–23. High risk adenoma (HRA) was defined at index or surveillance colonoscopy as a tubular adenoma ≥ 1 cm, 3 or more adenomas, or an adenoma with villous histology or high grade dysplasia. Low risk adenoma (LRA) was defined as 1 to 2 tubular adenomas < 1 cm11 without a villous component or high grade dysplasia. In this paper, we use the term serrated polyps to collectively refer to HP, SSA/P and TSA and use the term STSA to collectively refer to SSA/P and TSA as a single group for analysis throughout this manuscript. Serrated polyps at index colonoscopy were classified separately by size and histology.

Outcomes

The two findings of interest on the surveillance colonoscopy were metachronous HRA and/or serrated polyp ≥ 1 cm.

Index risk groups

The 5,433 NHCR participants were divided into three risk groups based on most advanced adenomatous findings at index colonoscopy: HRA (N= 817), LRA (N=1,418), and no adenomas (N=3,198). Within each risk group, patients were further categorized based on index serrated polyps, by size (< 1cm , ≥ 1cm, and unknown) and by histology (STSA and HP).

Statistical analysis

We report frequency distributions (N, %) and use chi-square tests to evaluate the associations of patient characteristics and index colonoscopy risk groups with metachronous findings. Two analyses were performed. The primary analysis compared participants with HRA (N=817) with or without synchronous serrated polyps and those with no adenoma (N=3,198) with or without synchronous serrated polyps at index colonoscopy. The secondary analysis included participants with LRA with and without synchronous serrated polyps (N=1,418) and those with no adenoma (N=3,198) with and without serrated polyps at index colonoscopy. For all analyses, participants with no polyps removed (N=2,124) as well as those where tissue on index colonoscopy was removed but the biopsy revealed non-adenomatous and non-serrated tissue (N=272) defined the common reference group of no adenoma and no serrated polyp (N=2,396).

Multivariable logistic regression models examined the effect of index findings on the two metachronous outcomes of HRA and serrated polyp ≥ 1 cm. Models were adjusted for patient characteristics, including age, gender, smoking status, BMI, and median time between colonoscopies. The model results are reported as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were conducted in SAS software, version 9.4 (Copyright, SAS Institute Inc. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

To determine if missed polyps accounted for metachronous lesions, we performed a sensitivity analysis of the risk for metachronous HRA or large SPs in NHCR participants who had an interim colonoscopy < 12 months after the index colonoscopy in addition to a colonoscopy > 12 months after index (these participants were not included in the current analysis). Furthermore, to address the question about residual or incompletely removed polyps, we compared the proportion of polyps that were considered by endoscopists to be partially or piecemeal excised/removed at the time of the index colonoscopy between the 2 groups.

Results

Among the 5,433 study participants, the median and interquartile range (IQR) age at index colonoscopy was 61 years (54–74 years) and the median (IQR) time between the index colonoscopy and surveillance colonoscopy was 4.9 years (3.0–5.3 years). Metachronous HRA were significantly more likely to occur in older participants (p < 0.0001) and those who were male (p < 0.0001). No significant associations were found between metachronous serrated polyps ≥ 1 cm and other patient related characteristics (Table 1). Frequency distributions are reported in Table 2 for the metachronous findings of interest (HRA and serrated polyps ≥ 1 cm) stratified by index findings of HRA and synchronous serrated polyps, the latter further categorized separately by size and by histology. At the index colonoscopy, 817 (15.0%) participants had a HRA and 1,016 (25.3%) had serrated polyps. Of the 4,015 participants in the HRA analysis, 299 (7.4%) had metachronous HRA and 49 (1.2%) had a metachronous large serrated polyp ≥ 1 cm (Table 2). At the time of the surveillance colonoscopy, 14 individuals were diagnosed with CRC.

Table 1.

Metachronous findings by patient characteristics from the index colonoscopy among 5,433 NHCR participants with 2 colonoscopies (1/2004 – 6/2015)

| Metachronous | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRA | SP ≥ 1 cm | ||||

| Total N = 5,433 | No N = 4,987 (91.8%) | Yes N = 446 (8.2%) | No N = 5,368 (98.8%) | Yes N = 65 (1.2%) | |

| Characteristics1 | N (col %) | N (col %) | N (col %) | N (col %) | N (col %) |

| Age at index colonoscopy (in years) | p<0.0001 | p=0.28 | |||

| 40–49 | 661 (12.2) | 630 (12.6) | 31 (6.9) | 656 (12.2) | 5 (7.7) |

| 50–59 | 2,241 (41.3) | 2,098 (42.1) | 143 (32.1) | 2,207 (41.1) | 34 (52.3) |

| 60–69 | 1,756 (32.3) | 1,586 (31.8) | 170 (38.1) | 1,743 (32.4) | 17 (26.2) |

| 70+ | 775 (14.3) | 673 (13.5) | 102 (22.9) | 766 (14.3) | 9 (13.8) |

| Gender | p<0.0001 | p=0.56 | |||

| Female | 2,731 (50.3) | 2,573 (51.6) | 158 (35.4) | 2,696 (50.2) | 35 (53.8) |

| Male | 2,702 (49.7) | 2,414 (48.4) | 288 (64.6) | 2,672 (49.8) | 30 (46.2) |

| Family history of CRC | p=0.07 | p=0.95 | |||

| No | 4,046 (80.4) | 3,706 (80.1) | 340 (83.7) | 4,000 (80.4) | 46 (80.7) |

| Yes | 988 (19.6) | 922 (19.8) | 66 (16.3) | 977 (19.6) | 11 (19.3) |

| Current smoking status | p=0.63 | p=0.19 | |||

| No | 4,346 (90.4) | 3,996 (90.5) | 350 (89.7) | 4,300 (90.5) | 46 (85.2) |

| Yes | 460 (9.6) | 420 (9.5) | 40 (10.3) | 452 (9.5) | 8 (14.8) |

| BMI | p=0.05 | p=0.83 | |||

| < 25 (Underweight and normal) | 1,293 (27.3) | 1,210 (27.6) | 83 (21.7) | 1,279 (27.2) | 14 (25.5) |

| 25 to < 30 (Overweight) | 1,854 (38.9) | 1,702 (38.8) | 152 (39.7) | 1,831 (38.9) | 23 (41.8) |

| 30 to < 35 (Obesity class I) | 1,051 (22.1) | 958 (21.9) | 93 (24.3) | 1,041 (22.1) | 10 (18.2) |

| 35 (Obesity classes II and III) | 567 (11.9) | 512 (11.7) | 55 (14.4) | 559 (11.9) | 8 (14.6) |

| Median time interval between colonoscopies (in years) | p=0.004 | p=0.06 | |||

| < 4.9 | 2,716 (50.0) | 2,464 (49.4) | 252 (56.5) | 2,676 (49.9) | 40 (61.5) |

| >= 4.9 | 2,717 (50.0) | 2,523 (50.6) | 194 (43.5) | 2,692 (50.1) | 25 (38.5) |

Abbreviation: NHCR = New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, CRC = colorectal cancer, BMI = body mass index, HRA=high risk adenoma, SP = serrated polyp

Missing (N): family history of CRC (399), current smoking status (627), BMI (668)

Table 2.

Metachronous findings by index colonoscopy findings characterized by high risk adenoma and serrated polyp (size and histology) among 4,015 NHCR participants with 2 colonoscopies (1/2004 – 6/2015)

| Metachronous | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRA | SP ≥ 1 cm | ||||

| Total N = 4,015 | No N = 3,716 (92.6%) | Yes N = 299 (7.4%) | No N = 3,966 (98.8%) | Yes N = 49 (1.2%) | |

| Index findings | N | N (row %) | N (row %) | N (row %) | N (row %) |

| Classification based on size of serrated polyps on index colonoscopy | |||||

| HRA (N =817) | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | |||

| SP ≥ 1 cm | 18 | 14 (77.7) | 4 (22.2) | 16 (88.8) | 2 (11.2) |

| SP < 1 cm | 140 | 111 (79.3) | 29 (20.7) | 139 (99.3) | 1 (0.7) |

| Unknown SP Size | 56 | 45 (80.4) | 11 (19.6) | 55 (98.2) | 1 (1.8) |

| No SP | 603 | 493 (81.8) | 110 (18.2) | 597 (99.0) | 6 (1.0) |

| No adenoma (N = 3,198) | |||||

| SP ≥ 1 cm | 65 | 63 (96.9) | 2 (3.1) | 57 (87.7) | 8 (12.3) |

| SP < 1 cm | 452 | 436 (96.5) | 16 (3.5) | 446 (98.7) | 6 (1.3) |

| Unknown SP Size | 285 | 274 (96.1) | 11 (3.9) | 278 (97.5) | 7 (2.5) |

| No SP | 2,396 | 2,280 (95.2) | 116 (4.8) | 2,378 (99.3) | 18 (0.7) |

| Classification based on histology of serrated polyps on index colonoscopy | |||||

| HRA (N =817) | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | |||

| STSA | 28 | 15 (53.6) | 13 (46.4) | 27 (96.4) | 1 (3.6) |

| HP Only | 186 | 155 (83.3) | 31 (16.7) | 183 (98.4) | 3 (1.6) |

| No SP | 603 | 493 (81.8) | 110 (18.2) | 597 (99.0) | 6 (1.0) |

| No adenoma (N = 3,198) | |||||

| STSA | 104 | 101 (97.1) | 3 (2.9) | 94 (90.4) | 10 (9.6) |

| HP Only | 698 | 672 (96.3) | 26 (3.7) | 687 (98.4) | 11 (1.6) |

| No SP | 2,396 | 2,280 (95.2) | 116 (4.8) | 2,378 (99.3) | 18 (0.7) |

Abbreviations: NHCR = New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, HRA=high risk adenoma, SP = serrated polyp, STSA = sessile and traditional serrated adenoma, HP = hyperplastic polyp

Participants with an index HRA were three times more likely to be diagnosed with metachronous HRA than the reference group with no adenomas and no serrated polyps (OR = 3.86, CI: 2.77 – 5.39) (Figure 2). Those with index HRA and a serrated polyp ≥ 1cm were over 5 times more likely to have a metachronous HRA than those in the reference group with no adenomas and no serrated polyps (OR = 5.61, 95% CI: 1.72 – 18.28). Patients with an HRA and synchronous STSA increased the risk of a metachronous HRA significantly (OR = 16.04, 95% CI: 6.95 – 37.00) compared to those with no adenoma and no serrated polyp on their index colonoscopy (Figure 2; Supplemental Table 1). Further, participants with HRA and synchronous STSA were over four times more likely to have a metachronous HRA on follow up than those with index HRA alone and no index SPs.

Figure 2.

Adjusted1 OR and 95% CI for metachronous high risk adenoma and serrated polyp ≥ 1cm by index colonoscopy findings of high risk adenoma and serrated polyp (size and histology) among 4,015 NHCR participants with 2 colonoscopies (1/2004–6/2015)

Abbreviations: OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, NHCR = New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, HRA=high risk adenoma, SP = serrated polyp, STSA = sessile or traditional serrated adenoma, HP = hyperplastic polyp

1Adjusted for patient age, gender, smoking status, BMI and median time between the 2 colonoscopies Reference line (1.00) = no adenoma and no serrated polyp; Blue diamond = OR and printed above diamond Note: All four panels scaled to 0–40; Index Findings (size) HRA, SP>1cm CI extends to 80 for SP ≥ 1 cm

After adjusting for co-variates, we observed that the risk for HRA on surveillance exam was not increased for the individuals with only STSA (adjusted OR=1.52 (0.74–3.11)) and those with only large serrated polyps (adjusted OR = 1.11, 95% CI: (0.40–3.14). The results of this adjusted analysis are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Adjusted1 OR and 95% CI for metachronous high risk adenomas among NHCR participants with large serrated polyps, STSA and no high risk adenomas on their index colonoscopy

| Metachronous HRA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index findings | N | No N (Row %) | Yes N (Row %) | OR2 95% CI |

| No HRA2 and SP ≥ 1 cm | 87 | 82 (94.3) | 5 (5.7) | 1.11 (0.40–3.14) |

| No HRA2 and STSA | 153 | 141 (92.2) | 12 (7.8) | 1.52 (0.74–3.11) |

| No HRA2, no LRA and no SP | 2,396 | 2,280 (95.2) | 116 (4.8) | Reference |

Abbreviation: NHCR = New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, HRA=high risk adenoma, SP = serrated polyp, STSA = sessile and traditional serrated adenoma

Adjusted for patient age, gender, smoking status, BMI and median time between the 2 colonoscopies

Includes low risk adenomas (LRA)

Participants with index large serrated polyps ≥1cm without synchronous HRA were much more likely to have metachronous serrated polyp ≥ 1cm (STSA: OR = 9.70, 95% CI: (3.63 – 25.92); serrated polyp ≥ 1cm: OR = 14.34, 95% CI(5.03 – 40.86)) than individuals with no adenoma and no serrated polyps at index colonoscopy (Figure 2; Supplemental Table 1).

With regards to the sensitivity analysis for missed polyps, we examined the risk of metachronous HRA and large SP in 105 NHCR participants who had an interim colonoscopy < 12 months after the index colonoscopy in addition to a colonoscopy ≥ 12 months; these 105 individuals were not included in the current analysis. There was no significant difference in risk for metachronous HRA or large serrated polyps between this group and the manuscript cohort (see Supplemental Table 2). To address the question about residual tissue, we compared the proportion of polyps that were considered by endoscopists to be partially or piecemeal excised/removed at the time of the index colonoscopy between the 2 groups. We found only 0.6% of the polyps were partially or piecemeal excised among the manuscript cohort as compared to 3.8% among those with an interim colonoscopy (p <0.0001). These data are in Supplemental Table 2.

For the secondary analysis, participants with an index LRA (N= 1,418) with synchronous small serrated polyps and those with LRA but without synchronous serrated polyps were nearly two to three times more likely to have a metachronous HRA than those with no adenoma and no serrated polyps (reference group) at index colonoscopy. Individuals with index LRA and synchronous large serrated polyps were at significantly higher risk for metachronous serrated polyps ≥ 1cm than those with no adenoma and no serrated polyps at index colonoscopy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusted1 OR and 95% CI for metachronous findings by index colonoscopy findings characterized by low risk adenoma and serrated polyp (size and histology) among 4,616 NHCR participants with 2 colonoscopies (1/2004 – 6/2015)

| Metachronous | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HRA N = 292 (6.3%) | SP ≥ 1 cm N = 55 (1.2%) | ||

| Total N= 4,616 | Adjusted | Adjusted | |

| Index findings | N (col %) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) |

| Classification based on size of serrated polyps on index colonoscopy | |||

| Low risk adenoma (N = 1,418) | |||

| SP ≥ 1 cm | 22 (0.5) | 1.83 (0.41–8.11) | 22.28 (5.50–90.34) |

| SP < 1 cm | 272 (5.9) | 2.09 (1.32–3.31) | 2.59 (0.93–7.17) |

| Unknown SP Size | 133 (2.9) | 2.90 (1.53–5.48) | 2.90 (0.64–13.16) |

| No SP | 991 (21.5) | 1.93 (1.41–2.62) | 0.31 (0.07–1.37) |

| No adenoma (N = 3,198) | |||

| SP ≥ 1 cm | 65 (1.4) | 0.83 (0.20–3.49) | 14.57 (5.19–40.88) |

| SP < 1 cm | 452(9.8) | 0.73 (0.42–1.28) | 1.20 (0.40–3.62) |

| Unknown SP Size | 285 (6.2) | 0.70 (0.28–1.76) | 4.82 (1.72–13.53) |

| No SP | 2,396 (51.9) | Reference | Reference |

| Classification based on histology of serrated polyps on index colonoscopy | |||

| Low risk adenoma (N = 1,418) | |||

| STSA | 49 (1.1) | 2.88 (1.67–7.13) | 9.33 (2.47–32.28) |

| HP Only | 378 (8.2) | 2.19 (1.45–3.31) | 2.80 (1.13–6.97) |

| No SP | 991 (21.5) | 1.93 (1.41–2.62) | 0.31 (0.07–1.37) |

| No adenoma (N = 3,198) | |||

| STSA | 104 (2.3) | 0.83 (0.26–2.70) | 10.29 (3.91–27.13) |

| HP Only | 698 (15.1) | 0.72 (0.43–1.19) | 1.96 (0.83–4.61) |

| No SP | 2,396 (51.9) | Reference | Reference |

Abbreviations: OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, NHCR = New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry, HRA=high risk adenoma, SP = serrated polyp, STSA = sessile and traditional serrated adenoma, HP = hyperplastic polyp

Adjusted for patient age, gender, smoking status, BMI and median time between the 2 colonoscopies

Discussion

Current surveillance recommendations for individuals with serrated polyps on colonoscopy are based on limited evidence. Our large cohort of over 5000 individuals with data from both index and surveillance colonoscopies allowed us to examine metachronous risk for individuals with index HRA or LRA, with synchronous serrated polyps stratified by size and histology separately. We observed that the presence of serrated polyps alone, regardless of whether the serrated polyps were classified by size or histology, was not associated with an increased risk for metachronous HRA.

Our analysis included 153 individuals with STSA without synchronous HRA and 87 with large (≥ 1 cm) serrated polyps without concurrent HRA, which allowed us to assess metachronous risk in individuals with clinically important serrated polyps without confounding by synchronous index HRA (see Table 4). The risk for HRA on surveillance exam was not increased for the individuals with only STSA (12/153; 7.8%) (OR=1.52 (0.74–3.11)) or those with large serrated polyps alone (5/87; 5.7%) (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: (0.40–3.14). Pereyra et al. reported a similar low risk of metachronous advanced neoplasia for individuals with only SSA/P (6.4%) but included only 47 such individuals in their analysis23. With a larger cohort of individuals with clinically important serrated polyps without concurrent HRA at index colonoscopy than other comparable studies,22, 23 our analysis yields a more reliable estimate of minimal risk for metachronous HRA in individuals with only serrated polyps on index colonoscopy.

Not surprisingly, index HRAs in our study predicted metachronous HRAs on surveillance colonoscopy. A recent smaller study of 157 individuals (compared to 1,016 in our sample) with serrated polyps on index colonoscopy also observed that index HRA were associated with metachronous HRA, while index serrated polyps were predictive of metachronous serrated polyps24. Thus, our data suggest that, unlike individuals with only conventional HRA on index colonoscopy, those with only clinically important serrated polyps on index exam may not be at increased short term risk for HRA at follow up colonoscopy.

Since lesions from both the adenomatous and the serrated pathway are present concurrently in many individuals14, data for adults with HRA and synchronous clinically important serrated polyps are needed to help guide surveillance. By analyzing individuals with HRA and no adenomas on index colonoscopy stratifed by serrated polyp histological type, we found that individuals with HRA and synchronous STSA were at much higher risk (more than 4 times) of metachronous HRA than those with HRA alone. Conversely, the presence of HRA and synchronous HPs or small serrated polyps at index colonoscopy was similar in risk to HRA alone for metachronous HRA. A possible implication of this finding is that among individuals with HRA at index colonoscopy, the subset of those who will gain the greatest benefit from close surveillance might be those with HRA and synchronous STSA.

Only a few large studies have examined the risk of metachronous neoplasia in individuals with serrated polyps on index colonoscopy25–29. A study of male veterans also found that individuals with proximal serrated polyps and HRA had a significantly greater risk for metachronous HRA compared to individuals with only HRA at baseline colonoscopy 29. However, the authors did not stratify serrated polyps by size or histology for the surveillance analysis and thus could not clarify whether the risk was for large serrated polyps or STSA or both. Another recent study also demonstrated that the metachronous HRA risk in individuals with index SSA/Ps was high only in those individuals who also had concurrent HRA23. However, due to a small number (<50) of HRA on surveillance colonoscopy, this study was unable to show a difference between individuals with index HRA and SSA/P and those with index HRA alone. Our large sample, consisting of 299 individuals with metachronous HRAs, afforded us enough power to clearly demonstrate a difference between these two groups.

We also examined the metachronous risk in individuals with low risk adenomas (LRA) and serrated polyps on index colonoscopy. The risk for metachronous HRA was lower for individuals with LRA and synchronous serrated polyps than those with HRA and synchronous serrated polyps. We found the risk of metachronous HRA to be similar for individuals with LRA with or without concurrent serrated polyps. In contrast, a recent study by Melson et al22 reported the rate of metachronous HRA to be higher in individuals with index low risk sessile serrated polyps with or without concurrent LRA as compared to individuals with LRA alone on index colonoscopy. One possible reason for the difference in findings is that the analysis by Melson et al pooled HRAs and large serrated polyps in the category of metachronous HRA for their outcome. Given potential differences between serrated polyps and conventional adenomas, we chose to examine the serrated and conventional outcomes separately.

While individuals with only large serrated polyps on index colonoscopy did not have an increased risk for metachronous HRA, they were 14 times more likely to have metachronous serrated polyp ≥1 cm than those with no adenoma and no serrated polyp. This has clinical relevance since previous studies have demonstrated an increased risk for CRC in individuals with large serrated polyps28, 30–33. However, this increased risk may occur over a protracted time period of 10 years or more,30, 34 and addressing variation in serrated polyp detection rates35 and completeness of resection36 may be more effective than a shorter surveillance interval at reducing risk in these individuals.

Strengths of our analysis include the ability to incorporate polyp size and histology, as suggested by the expert panel1 categorizing serrated polyps, allowing separation of analyses by serrated polyp size and histology. In addition, unlike the male-only VA study29, our analysis included equal numbers of men and women, improving the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, our reference group of participants with no findings provides useful comparison data to inform the development of surveillance guidelines in individuals with various combinations of findings at index colonoscopy.

There are some limitations to our study as well. Serrated polyp detection can be variable and lesions may have been missed at index colonoscopy3. We included colonoscopies from 1/2004 to 6/2015 and awareness regarding the importance of serrated polyp detection increased during the second half of this time period. While we relied on community pathologists’ diagnoses of the specific serrated polyp histology, which is recognized as irreproducible even among experts10, 37, we believe that our findings, by representing “real world practice,” have useful generalizability for practicing endoscopists. To address the issue of inconsistencies in the pathological interpretation of serrated polyps across pathology labs and pathologists, we classified study participants by size of serrated polyps as suggested by an expert panel1, in order to account for all serrated polyp ≥1 cm and minimize the impact of potential misclassification into various sub-types of serrated lesions12. It is surprising that we found a difference in risk associated with index STSAs and index large serrated polyps, since most of the latter are likely to be considered sessile serrated adenomas.12 We did not incorporate polyp location and morphology (flat vs polypoid) rather than histologic diagnosis per se. It is conceivable that the association with STSA in our study is related to right sided lesions and/or flat lesions, which are more likely to be missed or incompletely excised than the more distinct polypoid lesions amenable to complete resection. Finally, although our data highlight the risk of both HRA and serrated polyp ≥1 cm, and HRA and synchronous STSA, specific recommendations, such as intervals for surveillance, will require further study.

In conclusion, our data from a large cohort demonstrate that during a median follow up period of 4.9 years, individuals with synchronous HRA and STSA were at significantly increased risk for metachronous HRAs, compared to those with HRA alone at index colonoscopy. Individuals with index large serrated polyp ≥1 cm were more likely to have metachronous large serrated polyp ≥1 cm. Individuals with serrated polyp ≥1 cm have been identified by task forces as well as previous studies as being at higher risk for the development of metachronous CRC, with the task forces recommending 3 year surveillance intervals1, 11, 30 in individuals with serrated polyp ≥1 cm detected during colonoscopy. Our data, demonstrating that index serrated polyp ≥1 cm are associated with metachronous large serrated polyps and that STSA increase the risk for HRA in adults with HRA, support the recommendation that individuals with large and high risk serrated lesions require closer surveillance. Additional research is needed to further clarify the associations between index patient characteristics, polyp location, size, endoscopic appearance and histology, and the metachronous risk of advanced lesions and CRC in order to refine current surveillance recommendations for individuals undergoing colonoscopy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The project described was supported by Grants # R01CA131141, R21 CA191651 and Contract # HHSN261201400595P from the National Cancer Institute, as well as support from Norris Cotton Cancer Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

Abbreviations

- NHCR

New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry

- HRA

high risk adenoma

- STSA

sessile and traditional serrated adenoma

- HP

hyperplastic polyp

- LRA

low risk adenoma

- SP

serrated polyp

Footnotes

The contents of this work do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government

CONFLICT OF INTEREST The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Guarantors of the article: Joseph C. Anderson, M.D.; Julia E. Weiss, M.S.; Christina M. Robinson, M.S.; Amitabh Srivastava, M.D.; Lynn Butterly, M.D.

Specific Author Contributions

Conception and design: Anderson, Joseph C.; Weiss, Julia E.; Robinson, Christina M.; Butterly, Lynn, Srivastava, Amitabh, Amos, Christopher

Analysis and interpretation of the data: Anderson, Joseph C.; Weiss, Julia E.; Robinson, Christina M.; Butterly, Lynn, Srivastava, Amitabh, Amos, Christopher

Drafting of article: Anderson, Joseph C.; Weiss, Julia E.; Robinson, Christina M.; Butterly, Lynn

Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: Anderson, Joseph C.; Weiss, Julia E.; Robinson, Christina M.; Butterly, Lynn, Srivastava, Amitabh, Amos, Christophe

Final approval of the article: Anderson, Joseph C.; Weiss, Julia E.; Robinson, Christina M.; Butterly, Lynn, Srivastava, Amitabh, Amos, Christopher

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rex DK, Ahnen DJ, Baron JA, et al. Serrated lesions of the colorectum: review and recommendations from an expert panel. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2012;107:1315–29. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.161. quiz 1314, 1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JC, Butterly LF, Goodrich M, et al. Differences in detection rates of adenomas and serrated polyps in screening versus surveillance colonoscopies, based on the new hampshire colonoscopy registry. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2013;11:1308–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahi CJ, Hewett DG, Norton DL, et al. Prevalence and variable detection of proximal colon serrated polyps during screening colonoscopy. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2011;9:42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahi CJ, Li X, Eckert GJ, et al. High colonoscopic prevalence of proximal colon serrated polyps in average-risk men and women. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2012;75:515–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang J, Kalady MF, Appau K, et al. Serrated polyp detection rate during screening colonoscopy. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2012;14:1323–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snover DC, Ahnen DJ, Burt RW, et al. Serrated lesions of the colon and rectum and serrated polyposis. Tumours of the colon and rectum. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snover DC, Jass JR, Fenoglio-Preiser C, et al. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: a morphologic and molecular review of an evolving concept. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:380–91. doi: 10.1309/V2EP-TPLJ-RB3F-GHJL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tadros M, Anderson JC. Serrated polyps: clinical implications and future directions. Current gastroenterology reports. 2013;15:342. doi: 10.1007/s11894-013-0342-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalid O, Radaideh S, Cummings OW, et al. Reinterpretation of histology of proximal colon polyps called hyperplastic in 2001. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3767–70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farris AB, Misdraji J, Srivastava A, et al. Sessile serrated adenoma: challenging discrimination from other serrated colonic polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:30–5. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318093e40a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman DA, Rex DK, Winawer SJ, et al. Guidelines for colonoscopy surveillance after screening and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:844–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh H, Bay D, Ip S, et al. Pathological reassessment of hyperplastic colon polyps in a city-wide pathology practice: implications for polyp surveillance recommendations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1003–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiraoka S, Kato J, Fujiki S, et al. The presence of large serrated polyps increases risk for colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1503–10. 1510 e1–3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li D, Jin C, McCulloch C, et al. Association of large serrated polyps with synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:695–702. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Q, Tsoi KK, Hirai HW, et al. Serrated polyps and the risk of synchronous colorectal advanced neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2015;110:501–9. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.49. quiz 510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ng SC, Ching JY, Chan VC, et al. Association between serrated polyps and the risk of synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia in average-risk individuals. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2015;41:108–15. doi: 10.1111/apt.13003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buda A, De Bona M, Dotti I, et al. Prevalence of different subtypes of serrated polyps and risk of synchronous advanced colorectal neoplasia in average-risk population undergoing first-time colonoscopy. Clinical and translational gastroenterology. 2012;3:e6. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weaver DL, Rosenberg RD, Barlow WE, et al. Pathologic findings from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium: population-based outcomes in women undergoing biopsy after screening mammography. Cancer. 2006;106:732–42. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butterly LF, Goodrich M, Onega T, et al. Improving the quality of colorectal cancer screening: assessment of familial risk. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2010;55:754–60. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1058-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greene MA, Butterly LF, Goodrich M, et al. Matching colonoscopy and pathology data in population-based registries: development of a novel algorithm and the initial experience of the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:334–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martinez ME, Baron JA, Lieberman DA, et al. A pooled analysis of advanced colorectal neoplasia diagnoses after colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:832–41. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melson J, Ma K, Arshad S, et al. Presence of small sessile serrated polyps increases rate of advanced neoplasia upon surveillance compared with isolated low-risk tubular adenomas. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2016;84:307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereyra L, Zamora R, Gomez EJ, et al. Risk of Metachronous Advanced Neoplastic Lesions in Patients with Sporadic Sessile Serrated Adenomas Undergoing Colonoscopic Surveillance. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2016;111:871–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macaron C, Vu HT, Lopez R, et al. Risk of Metachronous Polyps in Individuals With Serrated Polyps. Diseases of the colon and rectum. 2015;58:762–8. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bensen SP, Cole BF, Mott LA, et al. Colorectal hyperplastic polyps and risk of recurrence of adenomas and hyperplastic polyps. Polyps Prevention Study Lancet. 1999;354:1873–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glazer E, Golla V, Forman R, et al. Serrated adenoma is a risk factor for subsequent adenomatous polyps. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2008;53:2204–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laiyemo AO, Murphy G, Sansbury LB, et al. Hyperplastic polyps and the risk of adenoma recurrence in the polyp prevention trial. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2009;7:192–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lazarus R, Junttila OE, Karttunen TJ, et al. The risk of metachronous neoplasia in patients with serrated adenoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:349–59. doi: 10.1309/VBAG-V3BR-96N2-EQTR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiner MA, Weiss DG, Lieberman DA. Proximal and large hyperplastic and nondysplastic serrated polyps detected by colonoscopy are associated with neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1497–502. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holme O, Bretthauer M, Eide TJ, et al. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer in individuals with serrated polyps. Gut. 2014 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu FI, van Niekerk de W, Owen D, et al. Longitudinal outcome study of sessile serrated adenomas of the colorectum: an increased risk for subsequent right-sided colorectal carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:927–34. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e4f256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oono Y, Fu K, Nakamura H, et al. Progression of a sessile serrated adenoma to an early invasive cancer within 8 months. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2009;54:906–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teriaky A, Driman DK, Chande N. Outcomes of a 5-year follow-up of patients with sessile serrated adenomas. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2012;47:178–83. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.645499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Erichsen R, Baron JA, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, et al. Increased Risk of Colorectal Cancer Development Among Patients with Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anderson JC, Butterly LF, Weiss JE, et al. Providing data for serrated polyp detection rate benchmarks: an analysis of the New Hampshire Colonoscopy Registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pohl H, Srivastava A, Bensen SP, et al. Incomplete Polyp Resection During Colonoscopy-Results of the Complete Adenoma Resection (CARE) Study. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:74–80. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aust DE, Baretton GB Members of the Working Group GIPotGSoP. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum (hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated adenomas, traditional serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps)-proposal for diagnostic criteria. Virchows Arch. 2010;457:291–7. doi: 10.1007/s00428-010-0945-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.