Abstract

While recent research suggests that people with schizophrenia anticipate less pleasure for non-social events, considerably less is known about anticipated pleasure for social events. In this study, we investigated whether people with and without schizophrenia differ in the amount and updating of anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated interactions as well as the influence of emotional displays. Thirty-two people with schizophrenia and 29 controls rated their anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated interactions with smiling, scowling, or neutral social partners that had either positive or negative outcomes. Compared to controls, people with schizophrenia anticipated a lower amount of pleasure during interactions with smiling, but not neutral social partners that had positive outcomes. However, the groups did not differ in the amount or updating of anticipated pleasure during interactions that had negative outcomes. Both groups anticipated more pleasure over the course of repeated interactions with smiling partners and less pleasure over the course of repeated interactions with scowling partners compared to interactions with neutral partners. We discuss how less anticipated pleasure for interactions with smiling social partners may be linked to difficulties in social engagement among people with schizophrenia.

Keywords: emotional displays, social functioning, learning, social engagement

1. Introduction

Whether meeting a friend for coffee or looking forward to seeing family around the holidays, many people anticipate pleasure from positive social encounters. Unfortunately, people with schizophrenia may not anticipate as much pleasure from the social world as those without schizophrenia. Indeed, people with schizophrenia often report less anticipated pleasure for future positive events compared to people without schizophrenia (Kring and Elis, 2013). However, nearly all of this research has focused on anticipated pleasure for non-social events. Less is known about anticipated pleasure for social events among people with schizophrenia, even as deficits in social engagement and social functioning are common (e.g., Robertson et al., 2014). In this study, we investigated anticipated pleasure for social interactions with either positive or negative outcomes, and whether emotional displays during social interactions might be associated with anticipated pleasure.

Recent work in affective and clinical science has parsed the experience of pleasure into consummatory (in the moment) and anticipatory components (e.g., Kring and Caponigro, 2010; Kring and Elis 2013). Studies assessing consummatory social pleasure have found that people with and without schizophrenia reported similar positive affect following a social role-play (Aghevli, Blanchard, and Horan, 2003) as well as when around other people in daily life (Oorschot et al., 2011). This is especially important as positive appraisals about past social interactions has been shown to predict the likelihood of future interactions among people with schizophrenia, suggesting that intact consummatory social pleasure may play an important role in promoting social engagement (Granholm et al., 2013). Further, a recent study examining the motivation for daily goals set by people with and without schizophrenia found that goals set in both groups were equally motivated by a desire for relatedness (Gard et al., 2014a). Despite behavioral evidence of intact consummatory social pleasure, studies using self-report measures, most commonly the Social Anhedonia Scale (SAS; Eckblad et al., 1982), have found that people with schizophrenia report less pleasure than controls from social activities (e.g., Blanchard et al., 1998; Horan, Blanchard, and Kring, 2006). This discrepancy may be explained by that fact that self-report measures, like the SAS, require participants to generate a mental representation of a hypothetical situation and then rate their pleasure experience, which creates an additional cognitive demand. Studies in the lab or in daily contexts, on the other hand, ask participants to rate their pleasure experience during or immediately after an actual experience or stimulus, likely reducing the cognitive demand for generating and maintaining a mental representation.

Studies of anticipated pleasure have largely focused on self-reported pleasure from future sensory and non-social events using the Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS; Gard et al., 2006). In a review of 23 studies using the TEPS, about half found that people with schizophrenia reported less anticipatory pleasure than controls (Frost and Strauss, 2016). Like the SAS, the TEPS also require participants to generate a mental representation of future events in order to rate anticipated pleasure, which likely creates an additional cognitive demand. In a study that assessed anticipated pleasure in daily life, Gard and colleagues (2007) found that, compared to controls, people with schizophrenia anticipated less pleasure for goal-directed activities. However, in a later study, Gard and colleagues found that people with schizophrenia reported greater anticipated pleasure daily life activities (Gard et al., 2014b). Methodological differences may account for these discrepancies: in the early study, participants responded to pages; in the later study, participants talked to an experimenter over the phone. In the lab, Wang and colleagues (2015) found that compared to controls, people with schizophrenia anticipated less pleasure for cues indicating potential monetary rewards. Edwards and colleagues (2015) asked people with and without schizophrenia to rate their anticipated pleasure for cues corresponding to positive images at high and low intensity levels. Relative to their rating of consummatory pleasure, people with schizophrenia anticipated greater pleasure for cues indicating low intensity stimuli and anticipated less pleasure for cues indicating high intensity positive stimuli. In sum, self-reported anticipated pleasure using the TEPS is the most commonly used approach, and the findings are mixed. Although there are fewer lab and daily life studies, on balance, these studies have more consistently found that people with schizophrenia anticipate less pleasure for future positive events.

While there have been several studies of consummatory social pleasure, there have been fewer studies of anticipated pleasure in the social domain. To date, only one study (Engel, Fritzsche, and Lincoln, 2016) investigated anticipated pleasure for social events in schizophrenia. In this study, people with and without schizophrenia were assigned to either a social inclusion (positive outcome) or social exclusion (negative outcome) condition in a computer game (Cyberball) and then asked to make a single rating of anticipated pleasure about being included or excluded from the upcoming game. In the inclusion condition, people with schizophrenia reported less anticipated pleasure than controls. No group differences were found in the exclusion condition.

In the current study, we sought to extend our understanding of anticipated pleasure in several ways. First, while the Engel and colleagues study (2016) found group differences in the amount of anticipated pleasure for positive outcomes based on one rating, they did not take advantage of the multiple trials in the game to also assess the extent to which people with schizophrenia updated anticipated pleasure based on the outcomes of experiences. Studies have consistently found that people with schizophrenia have comparative difficulties in using rewarding non-social (e.g., Gold et al., 2012; Strauss, Waltz, and Gold, 2014) and social outcomes (e.g., Campellone, Fisher, and Kring, 2016) to update subsequent decision-making, and as a result may be less likely to make decisions that result in future rewarding outcomes. We reasoned that people with schizophrenia will have difficulty using a positive social interaction outcome, such as a pleasant conversation with a friend, to update their anticipated pleasure for the next interaction, and as a result be less inclined to seek out a future interaction.

Second, for common sense reasons, most studies of anticipated pleasure have focused on positive events or outcomes, leaving open the question of whether deficits in anticipated pleasure are specific to positive outcomes. While people typically do not anticipate pleasure for negative outcomes, such outcomes may lessen anticipated pleasure. For example, a stressful meeting with a co-worker may lessen anticipated pleasure for the next work meeting. We reasoned that investigating anticipated pleasure for interactions with positive and negative outcomes would allow us to assess whether deficits in anticipated pleasure among people with schizophrenia are specific to positive outcomes, or also extend to negative outcomes. Indeed, evidence from Engel and colleagues (2016) suggests that deficits in anticipated social pleasure may be specific to positive social outcomes, consistent with studies using negative, non-social (Gold et al., 2012; Strauss, Waltz, and Gold, 2014) and social outcomes (e.g., Campellone, Fisher, and Kring, 2016) to update decision-making to avoid future negative outcomes.

Another factor that may influence anticipated pleasure in social interactions are emotional displays, which convey a social partner’s feelings and intentions during an interaction (e.g., Keltner and Kring, 1998; Van Kleef, 2009). Smiles have been shown to activate brain regions associated with the anticipation of reward (Rademacher et al., 2010) and facilitate learning from rewarding outcomes (Heerey, 2014). Scowls, on the other hand, signal rejection (e.g., Heerdink et al., 2015) and for others to keep their distance (Marsh et al., 2005), and as such may be associated with less anticipated pleasure in social interactions. Even though people with schizophrenia have difficulties accurately labeling emotional displays (e.g., Kohler et al., 2010), other evidence suggests people with schizophrenia implicitly use the information conveyed in emotional displays to guide subsequent behavior (e.g., Hooker et al., 2011; Kring et al., 2014; Campellone, Fisher, and Kring, 2016). Thus, people with schizophrenia may be able to implicitly use the information signaled by emotional displays to guide anticipated pleasure in social contexts.

1.1 Present Study

We tested three hypotheses and one exploratory aim. First, based on the Engel et al. (2016) study, we predicted that people with schizophrenia would anticipate less pleasure than controls from social interactions with positive, but not negative outcomes. We then explored group differences in the updating of anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated interactions with positive and negative outcomes. Second, given recent evidence (Hooker et al., 2011; Kring et al., 2014; Campellone, Fisher, and Kring, 2016), we predicted that people with schizophrenia would not differ from controls in their anticipated pleasure for social interactions with smiling and scowling social partners. Third, we predicted that anticipated pleasure for social interactions with positive, but not negative outcomes would be associated with social functioning among people with schizophrenia. To explore whether the association between anticipated pleasure and social functioning was influenced by social partner emotional displays, we also conducted these correlations separately for social partners with emotional (smile/scowl) and neutral displays.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Thirty-two people meeting DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria for schizophrenia (n= 20) or schizoaffective disorder (n= 12) and 29 healthy controls were recruited from outpatient mental health clinics and community advertisements. We calculated our sample size using G*Power software (Faul et al., 2007), using the effect size from Engel et al. (2016) as a basis for estimating the sample size. Participants were between the ages of 18 and 60, had no history of neurological disorders or serious head trauma, were fluent in English, had an estimated IQ > 70, and did not meet criteria for depression, mania, hypomania, or substance abuse in the past month or substance dependence in the last six months. Participants received $15 per hour for their participation in the study. Twenty-nine people in the schizophrenia group were taking medications; of these, 26 were taking atypical anti-psychotics.

2.2 Clinical Assessment

Diagnoses were confirmed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID-I/P; First et al., 2002a), and the absence of diagnoses for the control group was confirmed using the SCID non-patient version (SCID-I/NP; First et al., 2002b). We assessed negative symptoms using the Clinical Assessment Interview for Negative Symptoms (CAINS; Kring et al., 2013), and general symptoms using Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Lukoff et al., 1986). Given that the CAINS is a newer assessment instrument, we compared the scores for each CAINS subscale to those from the validation paper that contained a large, diverse, and representative sample of people with schizophrenia (n = 162; Kring et al., 2013). The current sample was very similar to the validation study sample on both the Motivation and Pleasure (MAP, Means: 15.0 and 14.2) and Expressivity scales (EXP, Means: 5.7 and 4.9). Functioning in the areas of work, self-care, family relationships, and social networks was assessed with the Role Functioning Scale (RFS; McPheters, 1984).

2.3 Social Interaction Task – Modified Trust Game

After providing informed consent, participants played a modified version of the Trust Game (Campellone, Fisher, and Kring, 2016) created using E-Prime 2.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA) and presented on a laptop computer. Instructions were designed to be self-explanatory and participants completed the task alone in a quiet testing room.

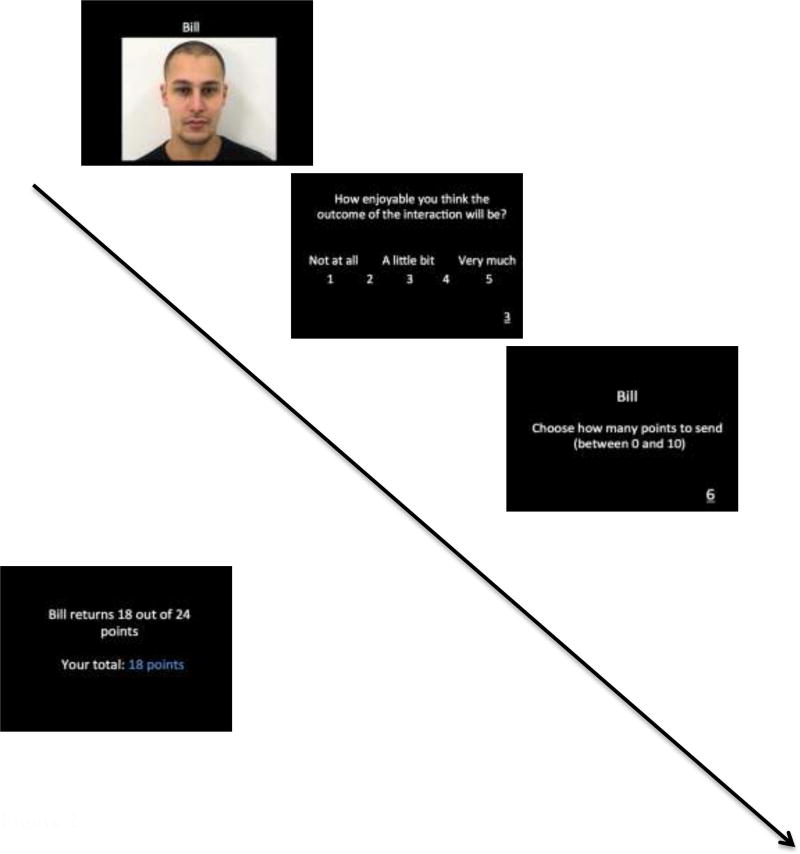

During the game, participants interacted with four simulated social partners, each identified by name and a dynamic 5s video of them expressing either an emotional (smile or scowl) or neutral facial display (see Figure 1). After seeing the partner’s name and display, participants were asked to rate the amount of pleasure they anticipated from the forthcoming outcome of this interaction by entering a number on the keyboard that corresponded to a 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) scale presented on the screen. Next, participants decided how many points to send to this partner, choosing an amount between 0 and 10 on the keyboard. The amount of points sent by the participant was then quadrupled, increasing the total number of available points. At this point, the social partner returned anywhere between 0 and 40 points to the participant.

Figure 1.

Example of a task trial. Participants first saw a dynamic clip and name of a social partner. Next, participants rated their anticipated pleasure for the outcome of the social interaction. Then, participants decided how many points to send to that partner and saw the outcome of the interaction, which showed the number of points returned by the social partner.

Participants interacted with each simulated social partner 10 times for a total of 40 trials. Interactions between participants and simulated social partners were conducted entirely using the computer monitor and keyboard and the only information that participants were provided about each social partner was their name, display, and the interaction outcome. The total amount of points a participant received did not accumulate across trials and was reset after each interaction. The order of interactions was pseudo-randomized so that participants never interacted with the same partner on consecutive trials.1

2.4 Social Interaction Outcomes and Displays

Social interaction outcomes were predetermined so that two social partner interactions resulted in positive outcomes (average return was equal to double the amount of points sent) and the other two social partner interactions resulted in negative outcomes (average return was equal to half the amount of points sent). For the two social partners with whom interactions resulted in positive outcomes, one exhibited a dynamic smile and the other exhibited no emotion (i.e., neutral display). For the two social partners with whom interactions resulted in negative outcomes, one exhibited a dynamic scowl and the other no emotion. Each social partner exhibited the same display for all interactions. Thus, ratings of anticipated pleasure reflected the degree to which participants anticipated enjoying the social partner’s decision to either honor (positive interaction outcome as indicated by more points returned on average) or reject (negative interaction outcome as indicated by fewer points returned on average) the trust placed in them.

Social partner emotional displays consisted of dynamic, 5s video clips of actors from the Amsterdam Dynamic Facial Expression Set (ADFES; Van der Schalk et al., 2011). The actors received instruction from coaches trained in the Facial Action Coding System (FACS; Ekman, Friesen, and Hagar, 2002). We chose 4 actors (2 men, 2 women), with one member of each gender expressing an emotion and the other expressing no emotion (i.e., a neutral display). Pairing of social partner gender and emotional display was counterbalanced so that half the sample within and across groups saw a male actor scowling and female actor smiling while the other half saw a male actor smiling and female actor scowling. The male and female videos were comparably rated by an independent sample (n = 12) of healthy adults on attractiveness, trustworthiness, and emotional intensity.

2.5 Statistical Analysis Plan

For our hypotheses and exploratory aim about group differences in the amount and updating of anticipated pleasure as well as the impact of emotional displays, we modeled changes in anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated social interactions using two, separate linear mixed effects regression models: one for interactions with positive outcomes and one for interactions with negative outcomes. A mixed-effect regression model can accommodate the nesting that occurs in the repeated measurement of the same people over time by modeling the random distribution of individual differences in level (random effect for intercept) and change over time (random effect for slope). These random effects are mixed with standard fixed-effects or model predictors, which yield a single regression coefficient for the sample (e.g. group status). We included the following fixed effect model predictors of anticipated pleasure ratings over the course of repeated social interactions with positive and negative outcomes: group (schizophrenia, control), emotion (smile/scowl, neutral), time (repeated social interactions). We also modeled all possible higher order interactions.

Within these models, a significant group main effect would indicate a group difference in the amount of anticipated pleasure while a significant Group X Time interaction would indicate that people with and without schizophrenia differed in their updating of anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated interactions. A Group X Emotion interaction, on the other hand, would indicate that people with and without schizophrenia differed in their anticipated pleasure for interactions with social partners with emotional and non-emotional displays. Model analyses were conducted using the lme4 package in R version 3.1.0 (R Core Team, 2013). For significant effects, we reported unstandardized beta coefficient estimates, standard errors, and effect sizes (Cohen’s d). For significant main and interaction effects, we tested conducted follow-up tests of simple effects using independent (for between subject effects) or paired samples t-tests (for within subject effects).

To investigate our third hypothesis, we computed correlations between the Social Network subscale of the RFS and the average ratings of anticipated pleasure for social interactions with positive and for interactions with negative. In addition, within each interaction outcome condition, we separately presented correlations for each social partner (emotional/non-emotional display).

3. Results

Demographic and clinical information is presented in Table 1. Participant gender, education, age, and estimated full-scale IQ were not significantly different between people with and without schizophrenia nor were they related to any study variables. Among people with schizophrenia, neither negative symptoms nor general symptoms were associated with anticipated pleasure for interactions with positive (CAINS MAP: r(32) = −0.28, ns, CAINS EXP: r(32) = −0.20, ns, BPRS: r(32) = 0.01, ns) or negative outcomes (CAINS MAP: r(32) = −0.02, ns, CAINS EXP: r(32) = −0.09, ns, BPRS: r(32) = −0.10, ns). Further, people with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder did not differ on any clinical variables or task performance, and we thus refer to this group as the schizophrenia group. There were no gender differences within either group for the amount of anticipated pleasure for interactions with positive and negative outcomes. Finally, there were no significant interactions between participant and social partner gender.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical variables

| Schizophrenia (n = 32) | Controls (n = 29) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 47.5 (11.9) | 46.2 (10.7) |

| Education | 14.7 (2.6) | 15.3 (1.8) |

| Parental Education | 14.7 (2.5) | 13.3 (3.3) |

| Sex (M/F) | 17/15 | 14/15 |

| WTAR | 105.4 (13.0) | 106.1 (9.9) |

| BPRS Total Score | 46.5 (13.7) | -- |

| CAINS | ||

| MAP scale | 15.0 (5.7) | -- |

| EXP scale | 5.7 (3.7) | -- |

| RFS | ||

| Work | 4.2 (2.0) | -- |

| Self-Care | 5.5 (1.2) | -- |

| Family | 4.9 (1.9) | -- |

| Social Networks | 4.7 (1.7) | -- |

WTAR = Wechsler Test of Adult Reading, Scale; BPRS = Brief Psychotic Rating Scale; CAINS = Clinical Assessment Inventory for Negative Symptoms; MAP = Motivation and Pleasure; EXP = Expressivity, RFS = Role Functioning Scale

3.1 Positive Social Interaction Outcomes

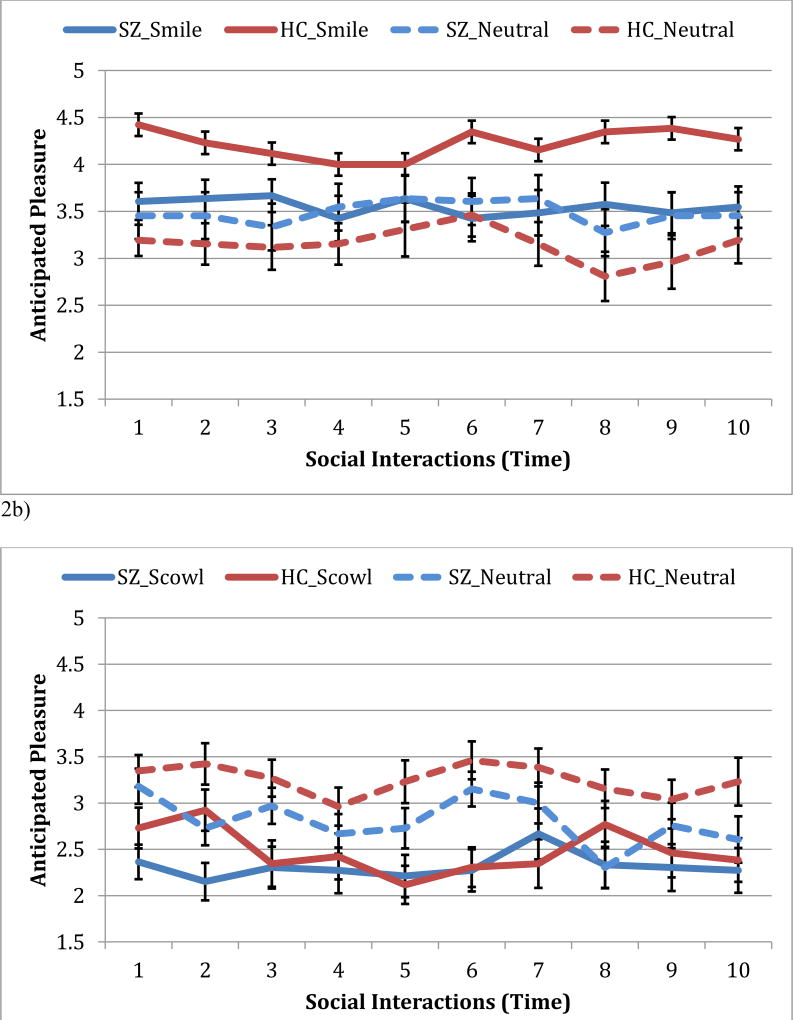

We did not find support for our first hypothesis or exploratory aim as the linear mixed effects regression model for interactions with positive outcomes revealed no group differences in either the amount or the updating of anticipated pleasure. However, we found partial support for our second hypothesis regarding group differences in the impact of emotional displays on anticipated pleasure. Specifically, we found a significant main effect of emotion that was qualified by both significant Time X Emotion interaction (see Figure 2a). Thus, while anticipated pleasure varied from interaction to interaction, both groups similarly used the used the information conveyed by a smile to update anticipated pleasure over the course of all 10 repeated interactions. The Group X Emotion interaction was also significant (see Figure 2a). Specifically, compared to controls, people with schizophrenia anticipated a lower amount of pleasure from positive outcome-interactions with smiling social partners, t(59) = 1.99, p = 0.05, d = 0.37, but not neutral social partners, t(59) = 0.29, p = 0.78 (see Figure 2a). No other effects were significant (p’s > 0.11).

Figure 2.

Anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated social interactions for people with and without schizophrenia. Figure 2a shows anticipated pleasure for social interactions resulting in positive outcomes with smiling and neutral social partners. Figure 2b shows anticipated displeasure for social interactions resulting in negative outcomes with scowling and neutral social partners. Note: SZ = schizophrenia, HC = healthy controls.

3.2 Negative Social Interaction Outcomes

Our results from the linear mixed effects regression model for interactions with negative outcomes revealed no group differences in the amount and updating of anticipated pleasure, consistent with expectations. In addition, the groups did not differ with respect to the impact of emotional displays on anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated social interactions (see Table 2). However, similar to our findings for interactions with positive outcomes, we found a significant emotion main effect that was qualified by a significant Time X Emotion interaction. Unpacking this Time X Emotion interaction, we found that both people with and without schizophrenia anticipated less pleasure over the course of repeated interactions with scowling, t(59) = 2.10, p = 0.04, d = 0.53 compared to neutral social partners, t(59) = −0.59, p = 0.56, d = 0.15 (see Figure 2b). No other effects were significant (p’s > 0.32).

Table 2.

Linear mixed effects regression results for predicted anticipated pleasure during social interactions with positive and negative outcomes.

| Interactions with Positive Outcomes |

Interactions with Negative Outcomes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | d [95% CI] | B | SE | t | d [95% CI] | |

| Intercept | 3.35 | 0.14 | -- | -- | 3.11 | 0.16 | -- | -- |

| Time | 0.01 | 0.01 | −1.63 | 0.42 [−0.09 to 0.02] | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.01 | 0.26 [−0.76 to 0.25] |

| Group | −0.10 | 0.20 | −0.49 | −0.13 [−0.38 to 0.63] | −0.28 | 0.22 | −1.27 | −0.33 [−0.83 to 0.18] |

| Emotion | 0.53*** | 0.13 | 4.11 | 1.05 [0.51 to 1.59] | −0.48*** | 0.13 | −3.71 | −0.95 [−1.48 to −0.42] |

| Group X Time | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.59 | −0.15 [−.65 to 0.35] | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.08 [−0.59 to 0.42] |

| Group X Emotion | −0.37* | 0.18 | −2.09 | −0.54 [−1.05 to −0.02] | −0.12 | 0.18 | −0.67 | 0.17 [−0.33 to 0.67] |

| Time X Emotion | −0.03* | 0.01 | −2.49 | −0.64 [−1.15 to −0.12] | 0.02* | .01 | 2.03 | 0.52 [−1.03 to −.01] |

| Group X Time X Emotion | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.68 | 0.17 [−0.33 to 0.68] | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 [−0.48 to 0.52] |

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

3.3 Correlations with Social Functioning

As predicted, we found that the average anticipated pleasure for interactions with positive outcomes was associated with social functioning, r(32) = 0.39, p = 0.02. Examining these associations separately for each social partner, we found that a significant association between anticipated pleasure and social functioning for interactions with smiling social partners, r(32) = 0.36, p = 0.04, but not neutral partners, r(32) = 0.32, p = 0.07. Average anticipated pleasure for interactions with negative outcomes was not significantly associated with social functioning, r(32) = 0.30, ns, nor for either scowling, r(32) = 0.08, ns, or neutral, r(32) = 0.32, ns, social partners.

4. Discussion

To date, there have been few studies of anticipated social pleasure in schizophrenia. Yet, people with schizophrenia often have lower levels of social engagement, which may be in part reflect diminished anticipated pleasure for social interactions. In this study, we investigated anticipated pleasure for social interactions with positive and negative outcomes among people with and without schizophrenia. To better elucidate the nature of anticipated social pleasure, we investigated both the amount and updating of anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated social interactions. Further, given that social partners often display emotion during interactions, and that emotional displays have been shown to influence anticipated pleasure for non-social outcomes (e.g., Rademacher et al., 2010), we investigated whether social partner emotional displays were associated with anticipated pleasure for social interaction outcomes.

For interactions with positive outcomes, we found that people with schizophrenia anticipated less pleasure than controls, but only during social interactions with smiling partners. Moreover, greater anticipated pleasure for social interactions with smiling partners was associated with better social functioning, pointing to its importance. In most contexts, smiles promote social engagement by signaling that someone is trustworthy (e.g., Scharlemann et al., 2001) and inviting social approach behavior (e.g., Knutson, 1996). Research with healthy people has shown that greater anticipated pleasure is linked to a greater likelihood of engaging in a particular course of action (e.g., Mellers and McGraw, 2001). Therefore, if people with schizophrenia anticipate comparatively less social pleasure from interactions with smiling social partners, then they may also be comparatively less likely to engage in social interactions with smiling social partners.

We did not find group differences in updating anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated interactions with positive outcomes as both groups anticipated more pleasure over the course of repeated interactions with smiling compared to neutral social partners. While exploratory, this finding is important as it suggests that decreases in the amount of anticipated pleasure was not due to difficulties learning from interactions with positive outcomes, but rather a failure to “catch up” to the anticipatory pleasure ratings made by controls. Further, while speculative, this finding also suggests that overcoming barriers to initial social engagement may pose the bigger challenge and that engaging in subsequent interactions may be comparatively easier due to intact updating. Why might people with schizophrenia anticipate a lower amount of pleasure for interactions with smiling partners, but still appear to have no difficulty in updating their pleasure over the course of repeated interactions? One possibility is that engaging in repeated interactions with the same social partners provided participants in both groups the opportunity to calibrate anticipated pleasure for subsequent social interactions, allowing all participants to use previous outcomes to guide their anticipated pleasure. Thus, people with schizophrenia may have been just as able as controls to use the outcome from a prior positive interaction to bolster anticipated pleasure for subsequent interactions.

Another speculative possibility is that people with schizophrenia may have more accurately predicted their pleasure for interactions with positive outcomes than controls. Research has shown that healthy people often overestimate the amount of pleasure for future positive events (e.g., Wilson and Gilbert, 2005), which has been posited to be adaptive and important for subsequent engagement in motivated behavior in healthy people (Mellers and McGraw, 2001; Greitemeyer, 2009; Miloyan and Suddendorf, 2015). People with schizophrenia, as was shown in the study by Edwards and colleagues (2015), may in fact underestimate their anticipated pleasure relative to their consummatory pleasure for high intensity positive stimuli. In other words, their anticipated pleasure may more closely approximate the in the moment experience of pleasure, with a possible consequence being diminished drive to engage in motivated behavior. In our study, it may be that interactions with smiling social partners were similar to the highly pleasant non-social stimuli in the Edwards and colleagues study, and that people with schizophrenia may have more accurately predicted (or even underestimated) the amount of pleasure for these interactions. If this is true, smiles may not facilitate social engagement in people with schizophrenia the way that they do in healthy people (e.g., Knutson, 1996). Unfortunately, we did not assess pleasure in response to these interactions and thus cannot compare these two ratings. Future studies should assess both anticipated and consummatory pleasure from social interactions in people with and without schizophrenia to more clearly determine whether group differences in anticipated pleasure amount may reflect an overestimation, underestimation, or potentially a combination of the two.

To determine whether potential deficits in anticipated pleasure were specific to social interactions with positive emotional displays and outcomes, we also investigated anticipated pleasure for interactions with negative emotional displays and outcomes. As expected and consistent with Engel and colleagues (2016), we did not find group differences in the amount of anticipated pleasure for negative social interaction outcomes. Our design also allowed us to assess the updating of anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated interactions with negative outcomes, and we also found no differences between people with and without schizophrenia. Together, our findings suggest that deficits in anticipated pleasure do not extend to negative social outcomes. Furthermore, our findings of no group differences in anticipated pleasure for negative social outcomes are in line with findings from previous studies that have shown intact use of negative non-social (e.g., Gold et al., 2012) and social (e.g., Campellone, Fisher, and Kring, 2016) outcomes to inform decision-making among people with schizophrenia. Thus, it appears that using negative outcomes to inform behavior may be a relative strength among people with schizophrenia.

These findings also add to the growing body of work suggesting that in some contexts people with schizophrenia modify their behavior based on the emotional display of another person (e.g., Hooker et al., 2011; Kring et al., 2014; Campellone, Fisher, and Kring, 2016). In the current study, we extended previous work by simultaneously investigating how people with and without schizophrenia use the information signaled by positive and negative emotional displays to inform the amount and updating of anticipated pleasure. Our results suggest that both groups used the information signaled by smiles and scowls to update anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated interactions relative to neutral displays. However, people with schizophrenia appear to have a specific difficulty in using smiles (but not scowls) to inform the amount of anticipated pleasure. While speculative given the nature of the interactions in this study, one possibility for this finding is that smiling displays were less rewarding for people with schizophrenia. While work in healthy people has shown that smiles activate reward areas of the brain (e.g., Rademacher et al., 2010), people with schizophrenia often show comparatively less activation in these brain areas during reward receipt (e.g., Radua et al., 2015). If people with schizophrenia found smiles to be less rewarding, this may have thus influenced their anticipated pleasure for these interactions. However, our results suggest the people with and without schizophrenia found scowls to be similarly un-rewarding.

Our findings have important implications for understanding the nature of decreased social engagement and poor social functioning in schizophrenia. A critical next step of this research will be to expand the investigation of anticipated pleasure for social interactions outside of the lab and into the lives of people with schizophrenia, similar to the approaches taken in previous studies (Granholm et al., 2013; Oorschot et al., 2013; Gard et al., 2014b). Two key unanswered questions are: 1) whether our findings of intact updating, but decreased amount of anticipated pleasure for positive outcomes is evident in daily life and predict real-world social engagement, and 2) whether a decrease in the amount of anticipated pleasure for social interactions with positive outcomes is due to an underestimation relative to healthy people, as Edwards and colleagues (2015) work suggests. Answering these questions could inform targeted approaches to promoting real-world social engagement by making people with schizophrenia more aware of a tendency to underestimate their anticipation of pleasure from future social interactions.

As with any study, it is important to acknowledge limitations. First, our study investigated how people with schizophrenia anticipated pleasure over the course of repeated simulated (computer) social interactions with positive and negative outcomes, not actual social interactions. Even though participants interacted with dynamic, virtual social partners, it is not the same as actual people. Future studies ought to extend this work to interactions between people in different social contexts. Second, the outcomes of the social interactions were expressed in terms of points. Future studies might seek to increase the social nature of interaction outcomes, possibly by using emotion displays as outcomes (e.g., Vrticka et al., 2008), or assess anticipated social pleasure in the context of participant’s daily lives (e.g., Granholm et al., 2013). Third, we did not assess consummatory pleasure, nor state positive or negative affect prior to the start of the task, which have been shown to influence the social interaction appraisal in people with schizophrenia (Granholm et al., 2013). By investigating both pleasure components as well as measuring affect, future studies can determine how these components might independently contribute as well as interact to influence social engagement among people with schizophrenia. Fourth, the pairing of emotional display (e.g., smile/scowl) and outcome (e.g., positive/negative) were always matched, and thus is unclear whether anticipated pleasure would track with social partner emotional display or interaction outcome when these two sources of information are in conflict (e.g., smile and negative outcome). Lastly, while our study extended the investigation of anticipated pleasure in people with schizophrenia by including anticipation of negative events and stimuli, our assessment did not include anticipated displeasure from these outcomes, which may be a distinct construct.

In summary, we found that anticipated pleasure for social interactions was largely intact among people with schizophrenia as group differences were limited to the amount of anticipated pleasure for interactions with smiling social partners. Our findings extend the literature on anticipatory pleasure in schizophrenia by showing that the amount and updating of anticipated pleasure, as well as the use of scowls to inform anticipated pleasure for interactions with negative outcomes was the same for people with and without schizophrenia.

Highlights.

People with schizophrenia often anticipate less pleasure for future positive non-social events and outcomes

In this study, we extended previous work by investigating anticipated pleasure for social interactions with positive and negative outcomes

We found that people with schizophrenia anticipated less pleasure for positive social outcomes, but only during interactions with smiling social partners

Anticipated pleasure for negative social interaction outcomes was intact

Deficits in anticipated pleasure for interactions with smiling social partners may contribute to decreased social engagement in people with schizophrenia

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Janelle Painter, Erin Moran, and Jasmine Mote for their help in collecting this data. We also thank Aaron Fisher who provided consultation on the analyses. We would also like to thank all the participants in this study.

Funding

US National Institutes of Mental Health grant 5T32MH089919 to TRC and 1R01MH082890 to AMK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The focus of this paper is on anticipated pleasure, results from the decision-making component of this study and an additional reversal learning phase, are published elsewhere (see Campellone, Fisher, and Kring, 2016).

Contributors

TRC designed the study as well as collected and analyzed the data. TRC and AMK wrote the manuscript.

References

- Aghevli MA, Blanchard JJ, Horan WP. The expression and experience of emotion in schizophrenia: a study of social interactions. Psychiatry Res. 2003;119:261–270. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.) Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barch DM, Dowd EC. Goal representations and motivational drive in schizophrenia: The role of prefrontal-striatal interactions. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:919–934. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JJ, Mueser KT, Bellack AS. Anhedonia, positive and negative affect, and social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24(3):413–424. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campellone TR, Fisher A, Kring AM. Using social outcomes to inform decision-making in schizophrenia: Implications for symptoms and functioning. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;25:310–321. doi: 10.1037/abn0000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RC, Wang Y, Huang J, Shi Y, Wang Y, Hong X, Ma Z, Li Z, Lai MK, Kring AM. Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure in schizophrenia: cross-cultural validation and extension. Psychiatry Res. 2010;175(1):181–183. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CJ, Cella M, Tarrier N, Wykes T. Predicting the future in schizophrenia: The discrepancy between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:462–469. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckblad ML, Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Mishlove M. The revised social anhedonia scale. Unpublished Test 1982 [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV, Hager JC. Facial action coding system: The manual on CD-ROM. Instructor's Guide. Salt Lake City: Network Information Research Co; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Engel M, Fritzsche A, Lincoln TM. Anticipation and experience of emotions in patients with schizophrenia and negative symptoms. An experimental study in a social context. Schizophr Res. 2016;170:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Patient Edition. Biometrics Research; New York: 2002a. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. Non-Patient Edition. Biometrics Research; New York: 2002b. [Google Scholar]

- Frost KH, Strauss GP. A review of anticipatory pleasure in schizophrenia. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2016;3(3):232–247. doi: 10.1007/s40473-016-0082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Gard MG, Kring AM, John OP. Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure: a scale development study. J Res Pers. 2006;40(6):1086–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Kring AM, Gard MG, Horan WP, Green MF. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: Distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophr Res. 2007;93:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Sanchez AH, Starr J, Cooper S, Fisher M, Rowlands A, Vinogradov S. Using self-determination theory to understand motivation deficits in schizophrenia: the ‘why’of motivated behavior. Schizophr Res. 2014a;156(2):217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard DE, Sanchez AH, Cooper K, Fisher M, Garrett C, Vinogradov S. Do people with schizophrenia have difficulty anticipating pleasure, engaging in effortful behavior, or both? J Abnorm Psychol. 2014b;123:771–782. doi: 10.1037/abn0000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Waltz JA, Matveeva TM, Kasanova Z, Strauss GP, Herbener ES, Gollins A, Frank MJ. Negative symptoms and the failure to represent the expected reward value of actions: Behavioral and computational modeling evidence. Arch Gen Psych. 2012;69:129–138. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granholm E, Ben-Zeev D, Fulford D, Swendsen J. Ecological momentary assessment of social functioning in schizophrenia: impact of performance appraisals and affect on social interactions. Schizophr Res. 2013;145(1):120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greitemeyer T. The effect of anticipated affect on persistence and performance. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2009;35(2):172–186. doi: 10.1177/0146167208326124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerdink MW, van Kleef GA, Homan AC, Fischer AH. Emotional expressions as social signals of rejection and acceptance: Evidence from the affect misattribution paradigm. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2015;56:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Heerey EA. Learning from social rewards predicts individual differences in self-reported social ability. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2014;143(1):332. doi: 10.1037/a0031511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Kring AM, Blanchard JJ. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: a review of assessment strategies. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:259–273. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker CI, Tully LM, Verosky SC, Fisher M, Holland C, Vinogradov S. Can I trust you? Negative affect priming influences social judgments in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:98–107. doi: 10.1037/a0020630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, Kring AM. Emotion, social function, and psychopathology. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2:320–342. [Google Scholar]

- Knutson B. Facial expressions of emotion influence interpersonal trait inferences. J Nonver Behav. 1996;20:165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Turner TH, Bilker WB, Brensinger CM, Siegel SJ, Kanes SJ, Gur RE, Gur RC. Facial emotion recognition in schizophrenia: Intensity effects and error patterns. Am J Psych. 2003;160:1768–1774. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler CG, Walker JB, Martin EA, Healey KM, Moberg PJ. Facial emotion perception in schizophrenia: A meta-analytic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:1009–1019. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Barch DM. The motivation and pleasure dimension of negative symptoms: neural substrates and behavioral outputs. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;24(5):725–736. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Caponigro JM. Emotion in schizophrenia where feeling meets thinking. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19(4):255–259. doi: 10.1177/0963721410377599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Elis O. Emotion deficits in people with schizophrenia. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:409–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Gur R, Blanchard J, Horan WP, Reise S. The clinical assessment interview for negative symptoms (CAINS): Final development and validation. Am J Psych. 2013;170:165–172. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, Siegel EH, Barrett LF. Unseen affective faces influence person perception judgments in schizophrenia. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2:443–454. doi: 10.1177/2167702614536161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J. Manual for the expanded Brief Psychotic Rating Scale. Schizophr Bull. 1986:594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh AA, Ambady N, Kleck RE. The effects of fear and anger facial expressions on approach-and avoidance-related behaviors. Emotion. 2005;5(1):119. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPheeters HL. Statewide mental health outcome evaluation: A perspective of two southern states. Comm Ment Health J. 1984;20:44–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00754103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellers BA, McGraw AP. Anticipated emotions as guides to choice. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001;10:210–214. [Google Scholar]

- Miloyan B, Suddendorf T. Feelings of the future. Trends Cog Sci. 2015;19(4):196–200. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oorschot M, Lataster T, Thewissen V, Lardinois M, Wichers M, van Os J, Delespaul P, Myin-Germeys I. Emotional experience in negative symptoms of schizophrenia—no evidence for a generalized hedonic deficit. Schizophr Bull. 2011;39:217–225. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rademacher L, Krach S, Kohls G, Irmak A, Grunder G, Spreckelmeyer KN. Dissociation of neural networks for anticipation and consumption of monetary and social rewards. Neuroimage. 2010;49:3276–3285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson BR, Prestia D, Twamley EW, Patterson TL, Bowie CR, Harvey PD. Social competence versus negative symptoms as predictors of real world social functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2014;160:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlemann JPW, Eckel CC, Kacelnik A, Wilson RK. The value of a smile: Game theory with a human face. J Econ Psychol. 2001;22:617–640. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Waltz JA, Gold JM. A review of reward processing and motivational impairment in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:S107–S116. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Schalk J, Hawk ST, Fischer AH, Doosje BJ. Moving faces, looking places: The Amsterdam Dynamic Facial Expressions Set (ADFES) Emotion. 2011;11:907–920. doi: 10.1037/a0023853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Kleef GA. How emotions regulate social life: The emotions as social information (EASI) model. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Vrticka P, Andersson F, Granjean D, Sander D, Vuilleumier P. Individual attachment style modulates human amygdala and striatum activation during social appraisal. PLoS One. 2008;3:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Huang J, Yang XH, Lui SS, Cheung EF, Chan RC. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: Deficits in both motivation and hedonic capacity. Schizophr Res. 2015;168:465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TD, Gilbert DT. Affective forecasting: Knowing what to want. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:131–134. [Google Scholar]