Abstract

Child depression is an impairing condition for which psychotherapies have shown modest effects. Parental depression is a risk factor for development of child depression and might also be negatively associated with child depression treatment outcomes. To explore this possibility, we analyzed data from a study in which children were treated for depression after parental depressive symptoms had been assessed at baseline. Among children treated for depression in a randomized controlled trial, we identified 31 who had child- and parent-report pre- and post-treatment data on child symptoms and parent-report of pre-treatment parental depressive symptoms. Children were aged 8-13, 77% boys, and 52% Caucasian, 13% African-American, 6% Latino, and 29% multi-racial. Analyses focused on differences in trajectories of change (across weekly measurements), and post-treatment symptoms among children whose parents did (n=12) versus did not (n=19) have elevated depressive symptoms at baseline. Growth curve analyses showed markedly different trajectories of change for the two groups, by both child-report (p = .03) and parent-report (p = .03) measures: children of parents with less severe depression showed steep symptom declines, but children of parents with more severe depression showed flat trajectories with little change in symptoms over time. ANCOVAs showed lower post-treatment child symptoms for children of parents with less severe depression versus parents with more severe depression (p = 0.05 by child report, p = 0.01 by parent report). Parental depressive symptoms predict child symptom trajectories and poorer child treatment response, and may need to be addressed in treatment.

Keywords: Children, depression, parent depression, internalizing symptoms, psychotherapy

Child depression is among the most impairing pediatric conditions (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2007). It constitutes a major public health concern, requiring effective interventions. Despite the need for such interventions, a meta-analysis of 35 youth depression treatment studies found only modest treatment benefits for youths with depression, with a mean effect size of 0.34, demonstrating that youth depression treatment is lagging behind treatments for other child conditions (Weisz, McCarty, & Valeri, 2006). One potential way to improve treatments' effectiveness may be to expand their focus to also target parental depression, which is one of the most salient risk factors for development of depression in children (Beardslee, Versage, & Gladstone, 1998; Cummings & Davies, 1994; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Kane & Garber, 2004; Phares & Compas, 1992).

Studies have documented that children of parents with depression have elevated risk of psychopathology, including depression and internalizing problems, across both childhood and adolescence (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare, & Neuman, 2000; Weissman, Warner, Wickramaratne, Moreau, & Olfson, 1997). A meta-analysis found that maternal depression was significantly related to higher levels of internalizing problems in their children (Goodman et al., 2011). A longitudinal study found that, at 10-year follow-up, children of parents with a lifetime history of depression have higher rates of Major Depressive Disorder (a 3-fold increase) compared to children of parents without depression (Weissman et al., 1997). Furthermore, the higher rates of depression were sustained from adolescence to adulthood in a 20-year follow-up assessment (Weissman, Wickramaratne, et al., 2006). Studies have identified a lifetime history of maternal depression as a risk factor for children's impaired functioning, disorders, and symptoms—especially internalizing symptoms (Nelson, Hammen, Brennan, & Ullman, 2003). Studies focusing on mothers with a current diagnosis of depression have found that their children have elevated rates of psychopathology, including depression (Batten et al., 2012; Pilowsky et al., 2006). Studies focusing on paternal depression have also found that depression in fathers is associated with internalizing symptoms in children (Kane & Garber, 2004).

There are several possible explanations for the association between parental depression and child and adolescent depression. One possible explanation might be related to genes, as research suggests that the importance of genetic factors in the etiology of depression in children and adolescence increases with age (Rice, Harold, & Thapar, 2003). Another possible explanation might be related to parenting problems that are associated with parental depression. Studies have found that parents with depression are more likely to exhibit withdrawn (e.g., emotional and behavioral withdrawal from offspring) and intrusive (e.g., irritability towards offspring) behaviors than parents who have not experienced depression (Jaser et al., 2008). A review found that mothers with depression were more critical and rejecting, expressed more negative affect towards their children, and were less sensitive to their children's needs (Berg-Nielsen, Vikan, & Dahl, 2002). When assessing the relations between parental depression, parenting, and child depression, studies found that disrupted parenting accounted for the association between parental depressive symptoms and children's internalizing symptoms (Reising et al., 2013). The influence of parental depression on parenting may extend beyond the confines of parents' depressive episodes, as documented in a study where children of parents with a history of depression continued to be exposed to disrupted parenting behaviors outside of the depressive episode of their parents (Jaser et al., 2005).

The association between parental depression and youth depression is further emphasized by studies that assessed the association between improvement in parents' depression and children's psychopathology. A review found that reduction or remission of parental depressive symptoms was related to reduction in child symptoms, including depressive and internalizing symptoms, and that these child effects were maintained in follow-up assessments (Gunlicks & Weissman, 2008). For example, studies that targeted depression in mothers using medication found that improvement in mothers' depression was associated with reduction in their children's psychopathology, including reduced depressive symptoms (Pilowsky et al., 2008; Weissman, Pilowsky, et al., 2006; Weissman et al., 2015; Wickramaratne et al., 2011). Improvement in parental depression as a mediator of improvement of their children was not assessed in relation to child's internalizing or depressive symptoms; however, a study of children with conduct problems found that maternal depression partially mediated the relation between intervention and improvement in child behavior (Hutchings, Bywater, Williams, Lane, & Whitaker, 2012). Such information is crucial for the development of more effective treatments for youth depression.

Studies have also demonstrated that parental depression is associated with less favorable intervention outcome in adolescent offspring. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) prevention programs have outperformed usual care (UC) in preventing depression in adolescents whose parents have a history of depression (Clarke, Hawkins, Murphy, & Sheeber, 1995; Clarke et al., 2001). However, current parental depression has been found to moderate child outcomes, both at immediate post-intervention and at 33-month follow-up (Beardslee et al., 2013; Garber et al., 2009). Specifically, CBT performed significantly better than UC in preventing depression in adolescents if the parent was not currently depressed; however, among adolescents with a currently-depressed parent, no significant difference between CBT and UC was observed at post-intervention or at follow-up (Beardslee et al., 2013; Garber et al., 2009). Another intervention study with adolescents with depression comparing CBT, systemic-behavioral family therapy, and nondirective supportive therapy demonstrated differential treatment response as a function of maternal depression: CBT outperformed the other two conditions when the mothers were not depressed, but not when the mothers had depressive symptoms (Brent et al., 1998). As efforts focus on identifying ways to improve the effectiveness of treatments for youths with depression, such information is necessary to understanding all components involved in successfully treating youth depression.

Despite research demonstrating that parental depression is one of the most potent risk factors for the development of depression in children and that parental depression has a negative influence on treatment outcomes in adolescents with depression, studies have not assessed the influence of parental depression on treatment outcomes in children with depression. This influence is important to assess, because parental depression is associated with an earlier onset and a more malignant course of depressive disorders in offspring (Lieb, Isensee, Höfler, Pfister, & Wittchen, 2002). Also, parents are likely more involved in the treatment of their child offspring compared to adolescent offspring. Therefore, in the present study, we investigated whether pre-treatment levels of parental depressive symptoms might be relevant to treatment response in children with depression. We used secondary analyses of data from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which children aged 8-13 were treated for depression. We assessed whether parental depressive symptoms were associated with children's response to treatment for depression. Specifically, we assessed whether baseline levels of parental depressive symptoms significantly predicted children's pattern of symptom change over the course of treatment. We also explored whether children with parents who had elevated levels of depressive symptoms would have a different response to treatment than children of parents without elevated depressive symptoms. Based on studies of adolescents with depression, we predicted different trajectories of change in symptoms depending on parental depressive symptoms, with steeper slopes of symptom reduction during treatment for children whose parents did not have elevated depressive symptoms than for children whose parents had elevated symptoms. We also predicted significant group differences following treatment completion between children whose parents had elevated versus non-elevated levels of depressive symptoms, with lower post-treatment symptom levels in children whose parents did not have elevated depressive symptoms. Since studies have found low parent-child agreement on child symptoms (Cantwell, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 1997; Garber, Van Slyke, & Walker, 1998), we assessed both child- and parent-report of child symptoms.

Method

Participants

The current study included 31 participants (Table 1). Participants were between the ages of 8 and 13 (mean age: 10.52) and 22.6% were females. The ethnic composition of the sample included 51.6% White/Caucasian, 12.9% African-American/Black, 6.5% Hispanic/Latino, and 29% multi-racial. Child depression diagnoses included 45.2% Major Depressive Disorder, 16.1% Dysthymia, 19.4% Depressive Disorder Not Otherwise Specified, and 19.4% with no diagnosis but with clinically elevated depressive symptoms on a standardized assessment measure. Parents were between the ages of 25 and 62 (mean age: 42.17) and 74.2% were females. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards of the universities and centers where the study was conducted. Informed consent and assent were obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Table 1. Sample Characteristics and Group Differences At Baseline.

| Sample Characteristics | Group Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite N (%) / M (SD) | Elevated Parental Depression N (%) / M (SD) | Non-Elevated Parental Depression N (%) / M (SD) | Exact p | Statistic | |

| Gender | 1.00 | .00b | |||

| Boys | 24 (77.4) | 9 (75.0) | 15 (78.9) | ||

| Girls | 7 (22.6) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| Age | .96 | .05c | |||

| Mean | 10.52 (1.48) a | 10.50 (1.73)a | 10.53 (1.35)a | ||

| Range | 8-13 | 8-13 | 8-12 | ||

| Grade | .66 | 4.11b | |||

| 2 | 2 (6.5) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (5.3) | ||

| 3 | 3 (9.7) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (5.3) | ||

| 4 | 6 (19.4) | 1 (8.3) | 5 (26.3) | ||

| 5 | 6 (19.4) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| 6 | 7 (22.6) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| 7 | 6 (19.4) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| 8 | 1 (3.2) | 1 (8.3) | - | ||

| Ethnicity | .12 | 5.83b | |||

| Caucasian | 16 (51.6) | 4 (33.3) | 12 (63.2) | ||

| African-American | 4 (12.9) | 1 (8.3) | 3 (15.8) | ||

| Latino | 2 (6.5) | 2 (16.7) | - | ||

| Mixed | 9 (29.0) | 5 (41.7) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| Income | .26 | 4.01b | |||

| Less than 40,000 | 19 (61.3) | 9 (75.0) | 10 (52.6) | ||

| 40,000-79,000 | 4 (12.9) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| 80,000-119,000 | 5 (16.1) | - | 5 (26.3) | ||

| Missing | 3 (9.7) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| Parents' Marital Status | .45 | 4.76b | |||

| Married | 10 (32.3) | 3 (25.0) | 7 (36.8) | ||

| Divorced | 8 (25.8) | 5 (41.7) | 3 (15.8) | ||

| Never Married | 4 (12.9) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (10.5) | ||

| Separated | 4 (12.9) | 1(8.3) | 3 (15.8) | ||

| Widowed | 3 (9.7) | - | 3 (15.8) | ||

| Living with a partner | 2 (6.5) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (5.3) | ||

| Parent Gender | .62 | .25b | |||

| Males | 8 (25.8) | 2 (16.7) | 6 (31.6) | ||

| Females | 23 (74.2) | 10 (83.3) | 13 (68.4) | ||

| Parents Age | 42.2 (10.4)a | 36.9 (7.7) | 45.7 (10.7)a | .02 | 2.44c |

| Range | 25-62b | 25-51 | 28-62b | ||

| Treatment Length (Days) | 211.58 (119.8) | 259.33 (154.7) | 181.42 (82.5) | .08 | -1.83b |

| Range | 35-462 | 35-462 | 37-333 | ||

| Parent Depressive | 54.16 (11.4) | 66.92 (5.9) | 46.11 (4.4) | .00 | -11.24c |

| Symptoms Child Internalizing | |||||

| Symptoms | |||||

| Child Report | 58.94 (6.5) | 61.71 (7.4) | 57.18 (5.4) | .06 | -2.00c |

| Parent Report | 68.48 (10.2) | 67.96 (8.8) | 68.82 (11.2) | .82 | .23c |

| Co-Morbid Diagnoses | .25 | 1.31b | |||

| Anxiety Disorder | 18 (58.1) | 9 (75.0) | 9 (47.4) | .16 | 2.02b |

| Conduct-Related Disorder | 17 (54.8) | 9 (75.0) | 8 (42.1) | ||

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | 17 (54.8) | 7 (58.3) | 10 (52.6) | 1.00 | .00b |

1 missing.

Chi Square.

T-Test

Procedure

Children and their parents were participants in an RCT investigating the effectiveness of evidence-based treatment and UC for depression, anxiety, and conduct problems (Weisz et al., 2012). Child inclusion criteria for the RCT study were: (a) 7 to 13 years of age, and (b) DSM–IV diagnosis or clinically elevated problem levels in the areas of depression, anxiety, and/or disruptive conduct. The age range reflected, in part, the psychometrics of the study measures (e.g., some of the measures had not been validated for children younger than 7) and, in part, developmental requirements and constraints of the treatment manuals employed, which set the upper limit of the age range at 13. Diagnoses were obtained via the Children's Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes (Weller, Weller, Rooney, & Fristad, 1999a, 1999b) and elevated problem levels (i.e., T scores ≥ 65) were identified through relevant scales of the Child Behavior Checklist and the Youth Self-Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Exclusion criteria included (a) intellectual disability, (b) pervasive developmental disorder, (c) psychotic symptoms, (d) primary bipolar disorder, and (e) primary inattention or hyperactivity. The presenting problem constituting the treatment focus was determined using information about the diagnosis, symptoms, and child- and parent-identified top problems (patient priorities).

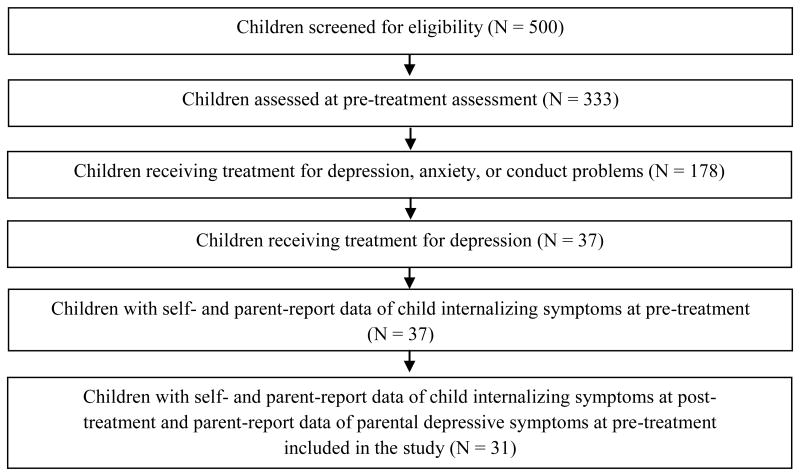

The groups in the current study were subsets of the 178 participants in the original study that received treatment for depression, anxiety, and conduct problems. To be included in the current study, participants had to be allocated to a treatment focusing on depression (n = 37) and have both child- and parent-report of pre- and post-treatment child symptoms and parents' report of their own pre-treatment symptoms (n = 31). Allocation to depression treatment reflected therapist judgment informed by clinical assessment, and standardized measures in the case of the two evidence-based treatment conditions (see below), and with child and parent input considered across study conditions. Children allocated to depression treatment were randomized to one of the study conditions detailed below (for further information see the parent study, Weisz et al., 2012). Figure 1 shows the participant flow from the RCT to the current study.

Figure 1.

Participant flow from enrollment for original RCT study to the current study.

Study Conditions

The RCT included three treatment conditions for depression, two CBT groups and one UC group. The CBT groups received treatment procedures from Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training (PASCET; (Weisz et al., 2005), an individual CBT protocol for depression. Some of the clinicians were randomly assigned to deliver these skills using the PASCET manual (n = 11; CBT1), while others delivered the same skills using a modular program that included additional treatment skills for additional problems (n = 14; CBT2; (Chorpita & Weisz, 2009). The UC (n = 6) group received treatment for depression from clinicians who used their preferred treatment approaches, unconstrained by the study; the UC approaches varied widely across clinicians, encompassing an eclectic range of relationship-building and supportive procedures.

Measures

Child Internalizing Symptoms

The Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) are parallel 118- item self- and parent-report measures of child behavioral and emotional problems. Children and parents rate each item on a 3-point scale: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true) and higher scores indicate increased level of symptoms. Both measures were administered prior to and following the treatment. Both measures generate a total problems scale, broadband syndrome scales, and eight narrowband syndrome scales. For the purpose of this study we averaged the T Scores of the two scales that involve depressive symptoms, Withdrawn/Depressed and Anxious/Depressed, referring to them as internalizing symptoms. The YSR and CBCL demonstrated good internal consistency for the scales and sample in this study (baseline alphas were .81 and .90 for YSR and CBCL, respectively). The YSR and CBCL have also previously shown strong content, criterion-related, and construct validity (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Weekly Child Problem Reports

The Brief Problem Checklist – Child and Parent (BPC; Chorpita et al., 2010), are parallel 12-item self- and parent-report measures assessing internalizing (6 items; scores can range from 0 to 12), externalizing (6 items; score range, 0-12), and total problems (12 items; score range, 0-24). The BPC was developed through application of item response theory and factor analysis to data from the YSR and CBCL, both previously described. Children and parents rate each item on a 3-point scale: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true or often true). In the RCT, the BPC was administered by telephone on a weekly basis to children and parents separately. In the present study, the BPC Internalizing scale (BPCI) was used to assess child- and parent-reported treatment trajectories. The six BPCI items include worries, sadness, self-consciousness, perceived worthlessness, fearfulness, and feeling guilty. Scores on the BPCI child-report are moderately correlated with the two YSR subscales (.65 and .46, respectively), and scores on the parent-report BPCI are moderately correlated with the two CBCL subscales (RS > .50). The BPCI demonstrated good internal consistency for the sample in this study (baseline alphas were .73 and .82 for child and parent, respectively). The BPC have also previously shown good validity with significant correlations between each BPC interview scale and the corresponding scales on the YSR and CBCL (Chorpita et al., 2010).

Parent Depressive Symptoms

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis, 1993). The BSI is a 52-item measure assessing parent psychopathology, including nine psychological symptom dimensions. Parents rate each item on a 5-point scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (a little bit), 2 (moderately), 3 (quite a bit) and 4 (extremely) for the previous week. For the purpose of this study we used the Depression Symptoms Dimension (BSI Depression), which reflects a representative range of indications of clinical depression. The depressive symptoms were assessed for the parent that was involved in the study prior to the treatment. T scores of 60 or higher were selected as representing elevated levels of depressive symptoms, as they place an individual at or above the 84th percentile of the normative population. The BSI Depression Dimension demonstrated good internal consistency (baseline alpha was .89) for the sample in this study. The BSI Depression Dimension has also shown strong convergent, discriminant, and construct validity (Derogatis, 1993).

Data Analyses

At baseline, the BSI parent depression variable was highly non-normally distributed; Shapiro Wilk's statistic = .79, p < .01. Specifically, its distribution had a strong positive skew. Values for the continuous BSI-Depression variable ranged from 0 to 2.67; however, the median and modal scores were 0.17 and 0, respectively. Due to non-normal distribution, interpretations of a continuous version of this variable would not be appropriate (Streiner, 2002). Thus, we created a binary BSI-Depression variable (using a median split) to address the significant positive skewness of the continuous version of the variable and used the BSI as a categorical (i.e., dichotomous) variable with “elevated” and “non-elevated” groups.

Baseline differences between children of parents with elevated versus non-elevated depressive symptoms were assessed using Chi Square for categorical variables and t-test for continuous outcomes. Baseline correlations were assessed using Pearson Correlation Coefficient for continuous variables and Point-Biserial Correlation for dichotomous and continuous variables.

We assessed whether parental depressive symptoms accounted for differences in children's pattern of symptom change across treatment by conducting growth curve modeling using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) in HLM 7.01 (Raudenbush, Bryk, & Congdon, 2012). This type of test is best conceptualized as comprising two levels (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1987; Singer & Willett, 2003). The level 1 model, or the intra-individual change model, examines person-specific growth rates. The level 2 model, or the inter-individual change model, captures between-person variability in the growth rates. At level 2, predictors may be added to the model to assess whether certain characteristics help explain differences in individuals' growth curves; in this study, we added parental depressive symptoms as a level 2 predictor. HLM has been used previously for evaluating treatment trajectories in small samples; for example, n=44 (Olatunji, Ciesielski, Wolitzky-Taylor, Wentworth, & Viar, 2012) and n=22 (White, Schry, Miyazaki, Ollendick, & Scahill, 2015); and has significant flexibility in accounting for missing data. For instance, HLM can incorporate all subjects for whom data are provided at two or more time points (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Thus, all 31 children were included in these models, despite variations in the number of weeks that children remained in treatment. Two HLM models were planned for this study. In the first model, child-reported symptoms (based on the BPCI) were specified as the outcome variable. Level 1 predictors were days into treatment (0 = 0 days into treatment, i.e. the first session; 100 = 100 days into treatment) and child age. The Level 2 predictor was dichotomous baseline parental depressive symptoms (elevated or non-elevated symptoms), created based on BSI-Depression subscale T scores (see description of measure above). The second model was identical to the first model, except that the outcome variable was parent-reported child symptoms (also based on the BPCI). In both models, a significant effect of the dichotomous parental depressive symptoms variable would indicate that baseline level of parental depressive symptoms predicted differences in children's symptom trajectories across treatment.

Prior to running the growth models described above, we ran the two preliminary models to determine whether a linear ([Days into treatment]), quadratic ([Days into treatment]2), or cubic ([Days into treatment]3) pattern best fit parent- and child-reported BPCI problem trajectories across treatment. These models followed the structure specified below (in the first model, child-report BPCI was the outcome variable; in the second, parent-report BPCI was the outcome variable):

Any significant growth trajectory term(s) in these preliminary models would be included in the final HLMs of interest.

Analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) following treatment completion was used to evaluate whether there were significant post-treatment differences in child- and parent-report of child symptoms between children whose parents had elevated versus non-elevated depressive symptoms, with pre-treatment child symptoms as the covariate. The outcome measures used in these analyses were YSR and CBCL internalizing symptoms. ANCOVA was used instead of HLM because HLM-based method would not offer information that is not available via the ANCOVA approach. ANCOVA is clearest and most straightforward analysis to address each of the analytic goals.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Of the total sample, 12 children had parents with elevated depressive symptoms on BSI Depression (elevated BSI), and 19 children had parents without elevated depressive symptoms on BSI Depression (non-elevated BSI). Table 1 includes baseline characteristics and Table 2 includes baseline correlations. No statistically significant differences between the groups were found for child's gender, child age, child grade level, child ethnicity, family income, parents' marital status, parents' gender, length of treatment, or child symptoms. Also, no statistically significant differences between the groups were found for child co-morbid diagnoses, including Conduct-Related Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorders (ADHD). As expected, there was a statistically significant difference between the groups on parental depressive symptoms. Also, there was a statistically significant difference between the groups for parents' age with large standard deviations, especially in the elevated BSI group. There was no significant correlation between child report of internalizing symptoms on the YSR and parent report of symptoms on the CBCL for the full sample (-.17, p = 0.37) and for the two groups considered separately (-.11, p = 0.73 for the elevated BSI group and -.21, p = 0.40 for the non-elevated BSI group).

Table 2. Baseline Correlations.

| Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| 1 | YSR Internalizing Symptomsa | 1 | ||||||

| 2 | CBCL Internalizing Symptomsa | -.17 | 1 | |||||

| 3 | BSIb | .34 | -.04 | 1 | ||||

| 4 | Genderbc | -.06 | -.19 | .05 | 1 | |||

| 5 | Ageb | -.10 | -.03 | -.01 | .26 | 1 | ||

| 6 | Gradeb | -.01 | -.05 | .02 | .25 | .95** | 1 | |

| 7 | Incomebd | -.20 | .37 | -.33 | .05 | -.17 | -.19 | 1 |

Note. YSR = Youth Self Report. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist. BSI = Brief Symptom Inventory.

p < .001.

Continuous variable.

Dichotomous variable.

Male = 1, Female = 2.

N=28

Parental Depressive Symptoms and Child Treatment Outcomes: I. Growth Curve Analyses

We tested whether elevated levels of parental depressive symptoms might be related to children's trajectories of change across treatment. Prior to running these models, we tested whether a linear, quadratic, or cubic growth term most parsimoniously described child-internalizing problems based on child- and parent-reports. In the model predicting child-reported child internalizing symptoms, only the linear growth term predicted symptom trajectories, coefficient = 2.76, t(29) = 7.13, p < .01 (ps = .19 and .16 for the quadratic and cubic terms, respectively). The same pattern emerged in the model predicting parent-reported child symptom trajectories, coefficient = 4.55, t(29) = 9.18, p < .01 (ps = .12 and .38 for the quadratic and cubic terms, respectively). Accordingly, only the linear growth terms were included in main study HLMs, described below.

Also, prior to running the models, we tested the variance linear slopes reflecting change in depressive symptoms to determine the appropriateness of subsequent tests for predictors (i.e., baseline parental depression). Significant variance emerged in children's individual trajectories of change in symptoms (i.e., variance components for the “Day” random slope were statistically significant in both parent- and child-report models, ps < .01; see Table 3), justifying our examining predictors and moderators of these trajectories. Thus, analyses were conducted as planned.

Table 3. Hierarchical Linear Modeling Predicting Child Depressive Symptoms, Using Weekly Symptom Ratings from Children (Model 1) and Parents (Model 2) Across Treatment.

| Model 1: DV = Youth-reported youth internalizing problems | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | t-ratio | df. | p-value |

| Intercept, π0 | |||||

| Intercept, β00 | -0.50 | 0.99 | -0.44 | 29 | 0.66 |

| Parental depressive symptoms, β01 | 2.30 | 0.70 | 3.49 | 29 | <0.01 |

| Days Into Treatment slope, π1 | |||||

| Intercept, β10 | -0.02 | 0.01 | -3.35 | 29 | <0.01 |

| Parental depressive symptoms, β11 | 0.01 | <0.00 | 2.35 | 29 | 0.02 |

| Child Age slope, π2 | |||||

| Intercept, β20 | -0.01 | 0.19 | -0.13 | 649 | 0.90 |

|

| |||||

| Random Effect | Variance Component | SD | χ2 | df | p-value |

|

| |||||

| Intercept, r0i | 3.65 | 1.91 | 551.23 | 29 | <0.01 |

| Day slope, r1 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 226.45 | 29 | <0.01 |

|

| |||||

| Model 2: DV = Parent-reported youth internalizing problems | |||||

| Fixed Effect | Coefficient | SE | t-ratio | df. | p-value |

|

| |||||

| Intercept, π0 | |||||

| Intercept, β00 | 1.50 | 1.64 | 0.09 | 29 | 0.37 |

| Parental depressive symtpoms, β01 | 1.49 | 0.79 | 1.85 | 29 | 0.04 |

| Days Into Treatment slope, π1 | |||||

| Intercept, β10 | -0.04 | 0.01 | -2.96 | 29 | 0.01 |

| Parental depressive symptoms, β11 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.32 | 29 | 0.03 |

| Child Age slope, π2 | |||||

| Intercept, β20 | 0.18 | 0.20 | 0.79 | 646 | 0.41 |

|

| |||||

| Random Effect | Variance Component | SD | χ2 | df | p-value |

|

| |||||

| Intercept, r0i | 5.46 | 2.34 | 401.26 | 29 | <0.01 |

| Day slope, r1 | <0.01 | 0.01 | 185.34 | 29 | <0.01 |

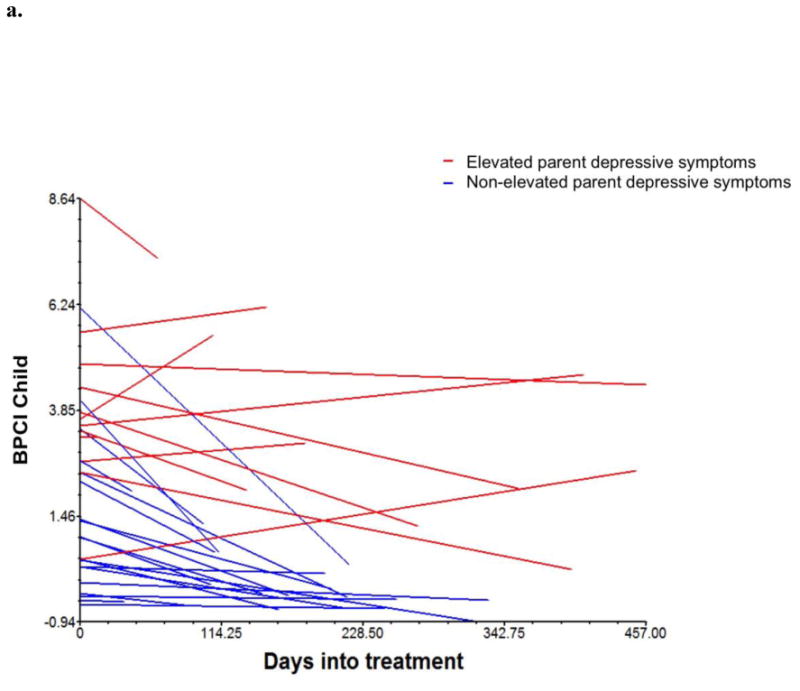

We first tested whether elevated versus non-elevated levels of parental depressive symptoms predicted child- and parent-reported trajectories of change across treatment. Results of Model 1, summarized in Table 3, showed a significant effect of baseline parental depressive symptoms, coefficient = 2.30, t(29) = 0.70, p < .01, indicating that parental depressive symptoms predicted differences in children's self-reported symptom trajectories across treatment on the BPCI-child report. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 2a, children of parents with elevated levels of depressive symptoms remained relatively stable in their self-reported symptoms over time (linear slope < .00, SE = .00, t = -.23, p = .83) whereas children of parents without elevated levels of depressive symptoms reported steep declines in their symptoms across treatment (linear slope = -.01, SE = .00, t = -4.40, p < .01).

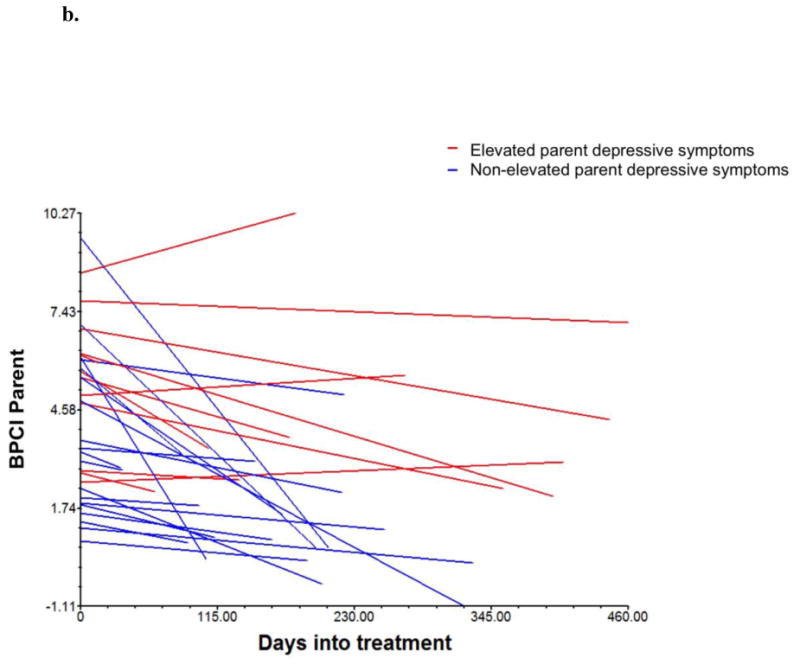

Figure 2a-2b.

Individual trajectories of child symptoms across treatment as a function of pre-treatment parental depressive symptoms, by child-report (2a) and parent-report (2b).

Mixed equation for both models:

The same pattern emerged based on Model 2, which included parents' weekly reports of child symptoms on the BPCI-parent report. Results of this model also showed a significant effect, coefficient = 1.49, t(29) = 1.79, p = .04. As in the child-report model, parental depressive symptoms predicted differences in parent-reported child symptom trajectories across treatment. Children of parents with elevated levels of depressive symptoms showed relatively flat symptom trajectories across treatment, linear slope < .00, SE = .00, t = -1.69, p = .16, whereas children of parents without elevated levels of depressive symptoms reported steep declines in symptoms across treatment, linear slope = -.02, SE = .01, t = -3.40, p = .01; see Figure 2b.

Parental Depressive Symptoms and Child Treatment Outcomes: II. ANCOVAS

We examined post-treatment outcome measures, using ANCOVA to control for pre-treatment child internalizing symptoms.1 We did not control for treatment condition due to the small sample size and because there were no significant differences between the treatment conditions in treatment outcome (i.e., children's internalizing symptoms). Analysis of child-reported internalizing symptoms on the YSR revealed that child symptom levels were lower at post-treatment for children of parents without elevated depressive symptoms (M = 52.13, SD = 3.50) than children of parents with elevated depressive symptoms (M = 56.46, SD = 6.10), F(1,28) = 4.09, p = .05, controlling for pre-treatment internalizing symptoms. Analysis of parent-reported child internalizing symptoms on the CBCL also showed a significant difference in the predicted direction. Child symptom levels were lower at post-treatment for children of parents without elevated depressive symptoms (M = 56.58, SD = 6.05) than children of parents who had elevated depressive symptoms (M = 62.83, SD = 8.21), F(1,28) = 7.55, p = .01.

Discussion

Despite research indicating that parental depression is a salient risk factor for development of depression in children, studies have not assessed the relation of parental depression to treatment outcome in children with depression. The influence of parental depression has been examined in relation to treatment outcome in children with anxiety (Berman, Weems, Silverman, & Kurtines, 2000; Liber et al., 2008) and adolescents with depression (Beardslee et al., 2013; Brent et al., 1998; Garber et al., 2009); however, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to address this question in relation to treatment of children with depression. The findings showed that, in a sample of clinically-referred children, parental depressive symptoms predicted child depression treatment trajectories, and that children of parents who had elevated levels of depressive symptomatology fared worse in depression treatment than children whose parents did not have elevated depression symptoms. These findings suggest that it may be important to consider parental depressive symptoms when treating child depression. Although these findings are preliminary, they highlight the potential value of a larger sample study.

Elevated levels of parental depressive symptoms predicted flatter child symptom trajectories during treatment and worse child outcomes at the end of treatment. If this finding were to prove robust in future research, it could raise important questions regarding the role of parents in child depression treatment. The fact that parent depression predicted worse child treatment response might reflect a depression-generated dampening of parents' ability to support their child's recovery (e.g., limited ability to help the child practice skills learned in therapy, or to model cognitive restructuring), parenting difficulties (as discussed previously), a more genetically-based and treatment-resistant form of child depression, a more chronic or recurrent course of parental depression, more extensive exposure to stressful life events, or multiple other explanations that warrant empirical attention (Beardslee et al., 2013).

The findings may also carry clinical implications for child depression treatment. It is possible that treatment of children whose parents are depressed might be made more effective by strengthening the dose of child CBT or by supplementing CBT with complementary treatment strategies to help the child learn to cope with the stress of living with a parent with depression (Jaser et al., 2005). Another option may involve offering a more comprehensive range of services to the family that include treatment for the parents to address their depression either prior to treating the child or as an adjunctive treatment (Beardslee et al., 2013). As previously discussed, studies that have targeted depression in mothers using medication have found that improvement in mothers' depression was associated with reduction in their children's psychopathology, including reduced depressive symptoms (Pilowsky et al., 2008; Weissman, Pilowsky, et al., 2006; Weissman et al., 2015; Wickramaratne et al., 2011). One other way may be to address the parent patterns that may be associated with parental depression, as previously discussed (Sander & McCarty, 2005). No study has addressed parental depression by targeting the parent or family patterns. However, pilot studies that treated child depression by addressing patterns that characterize families of children with depression, such as negative communication and low level of support, by either targeting only the family (Tompson et al., 2007) or by delivering individual child treatment along with parent training (Eckshtain & Gaynor, 2012, 2013), found positive treatment outcomes for child depression. Our findings that parental depressive symptoms predict child symptom trajectories and poorer child treatment response, together with the findings that existing treatments demonstrate only moderate outcomes, suggest that we need to focus on developing more effective treatments, which may include, but are not limited to, one or more of these options.

Baseline correlations documented low parent-child agreement on child symptoms for the full sample and for the two groups considered separately. Although some studies suggested that children often report more internalizing problems than parents (Grills & Ollendick, 2002) and that children are better reporters of internalizing problems (Epkins, 1996), we found that even though both children and parents reported elevated levels of symptoms, the parents reported higher levels than the children. Also, despite some studies suggesting that parental depression is associated with parent-child disagreement (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2005), we found low agreement in both the elevated parent BSI group and the non-elevated parent BSI group. This is consistent with two previous studies. One study assessed agreement on depressive symptoms in 5-13-year-old children in a psychiatric inpatient care facility and found that the children consistently rated themselves as less depressed than their parents (Kazdin, French, & Unis, 1983). Similarly, a study with youth ages 6 to 18 found that the mothers reported more depressive symptoms than the children (Garber et al., 1998). This finding emphasizes the importance of assessing both child- and parent-report of child symptoms when treating children with depression.

Study limitations include the small sample size, which limited power of the statistical analyses. The small sample also made it impossible to fairly test age and gender effects, which should certainly be addressed in future research with larger samples. Another limitation includes the inclusion of children from three treatment groups. The use of self- and parent-report measures and the lack of clinician-rated measures is another limitation. Also, another limitation, common in this field, is that we had information about parental depressive symptoms from only one parent. On the one hand, this produced a relatively conservative test of the association between parent depression and child outcome, but information from both parents would provide a more comprehensive perspective and would be valuable in future research. It would also be useful, in the future, to assess parental depression throughout child treatment, to evaluate the impact of continuity and change in parent symptomatology. In addition, parental depression may be associated with multiple other risk factors (e.g., low SES, high stress, even genetic risk), which might contribute to reduced success of child treatment and were not assessed in the current study. These risk factors warrant attention in future research with larger samples than that of the present study, including the assessment of processes and mechanisms that might explain the relation between parental depression and treatment outcome. Furthermore, the continuous version of the BSI-Depression variable was non-normally distributed with a strong positive skew. Thus, instead of using it as a continuous variable we created a binary BSI-Depression variable using a median split. The study limitations suggest strategies through which future research may sharpen the picture of the connection between parent depression and child depression treatment, and what may be done to improve child treatment outcomes.

In summary, we compared treatment trajectories and post-treatment internalizing symptoms in children who received treatment for depression and whose parents did, versus did not, have elevated depressive symptoms at baseline. We found that children of parents with less severe depression showed steep symptom declines during treatment and lower levels of post-treatment symptoms compared to children of parents with more severe depression who showed flat trajectories and higher levels of post-treatment symptoms. These results suggest that parental depressive symptoms predict child symptom trajectories and treatment response and should be considered when treating child depression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant K23MH093491 (D. Eckshtain, P.I.) from the National Institute of Mental Health, and the parent study was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Norlien Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: John Weisz receives royalties for some of the work cited in this paper, including the MATCH-ADTC treatment manual used in the study

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Analysis of child-reported internalizing symptoms using the Anxious/Depressed scale of the YSR revealed that child symptom levels were significantly lower at post-treatment for children of parents without elevated depressive symptoms (M = 50.89, SD = 2.42) than children of parents with elevated depressive symptoms (M = 56.17, SD = 6.26), F(1,28) = 9.08, p = .01, controlling for pre-treatment scores on the Anxious/Depressed scale. Analysis of child-reported internalizing symptoms using the Withdrawn/Depressed scale of the YSR showed that child symptom levels were in the predicted direction, albeit not significantly different at post-treatment for children of parents without elevated depressive symptoms (M = 53.37, SD = 5.33) than children of parents with elevated depressive symptoms (M = 56.75, SD = 7.78), F(1,28) = .81, p = .38.

Analysis of parent-reported child internalizing symptoms using the Anxious/Depressed scale of the CBCL showed a significant difference in the predicted direction. Child symptom levels were lower at post-treatment for children of parents without elevated depressive symptoms (M = 55.37, SD = 5.89) than children of parents who had elevated depressive symptoms (M = 63.50, SD = 8.85), F(1,28) = 10.09, p < .01, controlling for pre-treatment scores on the Anxious/Depressed scale. Analysis of parent-reported internalizing symptoms using the Withdrawn/Depressed scale of the CBCL revealed that child symptom levels were in the predicted direction at post-treatment for children of parents without elevated depressive symptoms (M = 57.79, SD = 7.57) than children of parents with elevated depressive symptoms (M = 62.17, SD = 9.17), F(1,28) = 3.19, p = .09.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Dikla Eckshtain, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School 185 Cambridge Street, Boston, MA 02114

Lauren Krumholz Marchette, Department of Psychiatry, Cambridge Health Alliance, Harvard Medical School 1493 Cambridge St, Cambridge, MA 02139

Jessica Schleider, Department of Psychology, Harvard University 1032 William James Hall, 33 Kirkland Street, Cambridge, MA 02138

John R. Weisz, Department of Psychology, Harvard University 1030 William James Hall, 33 Kirkland Street, Cambridge, MA 02138

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1503–1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batten LA, Hernandez M, Pilowsky DJ, Stewart JW, Blier P, Flament MF, Weissman MM. Children of treatment-seeking depressed mothers: A comparison with the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STARD) Child Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:1185–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Brent DA, Weersing VR, Clarke GN, Porta G, Hollon SD, Garber J. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: Longer-term effects. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1161–1170. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee WR, Versage EM, Gladstone TRG. Children of affectively ill parents: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1134–1141. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199811000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Nielsen TS, Vikan A, Dahl AA. Parenting related to child and parental psychopathology: A descriptive review of the literature. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:529–552. [Google Scholar]

- Berman SL, Weems CF, Silverman WK, Kurtines WM. Predictors of outcome in exposure-based cognitive and behavioral treatments for phobic and anxiety disorders in children. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31:713–731. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(00)80040-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Kolko DJ, Birmaher B, Baugher M, Bridge J, Roth C, Holder D. Predictors of treatment efficacy in a clinical trial of three psychosocial treatments for adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:906–914. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:147–158. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell DP, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Correspondence between adolescent report and parent report of psychiatric diagnostic data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:610–619. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199705000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Reise S, Weisz JR, Grubbs K, Becker KD, Krull JL. Evaluation of the Brief Problem Checklist: Child and caregiver interviews to measure clinical progress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:526–536. doi: 10.1037/a0019602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Weisz J. Modular Approach to Therapy for Children with Anxiety, Depression, Trauma, or Conduct problems (MATCH-ADTC) Satellite Beach, FL: PracticeWise, LLC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Hawkins W, Murphy M, Sheeber LB. Targeted prevention of unipolar depressive disorder in an at-risk sample of high school adolescents: A randomized trial of group cognitive intervention. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34:312–321. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199503000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Hornbrook M, Lynch F, Polen M, Gale J, Beardslee W, Seeley J. A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention for preventing depression in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Kazdin AE. Informant Discrepancies in the Assessment of Childhood Psychopathology: A Critical Review, Theoretical Framework, and Recommendations for Further Study. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:483–509. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Eckshtain D, Gaynor ST. Combining individual cognitive behaviour therapy and caregiver–child sessions for childhood depression: An open trial. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;17:266–283. doi: 10.1177/1359104511404316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckshtain D, Gaynor ST. Combined individual cognitive behavior therapy and parent training for childhood depression: 2- to 3-year follow-up. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2013;35:132–143. doi: 10.1080/07317107.2013.789362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epkins CC. Parent ratings of children's depression, anxiety, and aggression: A cross-sample analysis of agreement and differences with child and teacher ratings. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996;52:599–608. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199611)52:6<599::aid-jclp1>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Clarke GN, Weersing VR, Beardslee WR, Brent DA, Gladstone TRG, Iyengar S. Prevention of depression in at-risk adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:2215–2224. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Van Slyke DA, Walker LS. Concordance between mothers' and children's reports of somatic and emotional symptoms in patients with recurrent abdominal pain or emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:381–391. doi: 10.1023/a:1021955907190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE, Ollendick TH. Issues in parent-child agreement: The case of structured diagnostic interviews. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:57–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1014573708569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunlicks ML, Weissman MM. Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:379–389. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings J, Bywater T, Williams ME, Lane E, Whitaker CJ. Improvements in maternal depression as a mediator of child behaviour change. Psychology. 2012;3:795. [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, Fear JM, Reeslund KL, Champion JE, Reising MM, Compas BE. Maternal sadness and adolescents' responses to stress in offspring of mothers with and without a history of depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:736–746. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, Langrock AM, Keller G, Merchant MJ, Benson MA, Reeslund K, Compas BE. Coping with the stress of parental depression II: Adolescent and parent reports of coping and adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:193–205. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane P, Garber J. The relations among depression in fathers, children's psychopathology, and father-child conflict: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:339–360. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, French NH, Unis AS. Child, mother, and father evaluations of depression in psychiatric inpatient children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1983;11:167–180. doi: 10.1007/bf00912083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liber JM, van Widenfelt BM, Goedhart AW, Utens EMWJ, van der Leeden AJM, Markus MT, Treffers PDA. Parenting and parental anxiety and depression as predictors of treatment outcome for childhood anxiety disorders: Has the role of fathers been underestimated? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:747–758. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieb R, Isensee B, Höfler M, Pfister H, Wittchen HU. Parental major depression and the risk of depression and other mental disorders in offspring: A prospective-longitudinal community study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:365–374. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.4.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DR, Hammen C, Brennan PA, Ullman JB. The impact of maternal depression on adolescent adjustment: The role of expressed emotion. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:935–944. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.5.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Ciesielski BG, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Wentworth BJ, Viar MA. Effects of experienced disgust on habituation during repeated exposure to threat-relevant stimuli in blood-injection-injury phobia. Behavior Therapy. 2012;43:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Compas BE. The role of fathers in child and adolescent psychopathology: Make room for daddy. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:387–412. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Talati A, Tang M, Hughes CW, Garber J, Weissman MM. Children of depressed mothers 1 year after the initiation of maternal treatment: Findings from the STARD child study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1136–1147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Rush AJ, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, Weissman MM. Children of Currently Depressed Mothers: A STARD Ancillary Study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:126–136. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatry A. A. o. C. a. A. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1503–1526. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318145ae1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Vol. 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Congdon R. HLM for Windows (Version 7.01) [Computer Software] Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reising MM, Watson KH, Hardcastle EJ, Merchant MJ, Roberts L, Forehand R, Compas BE. Parental depression and economic disadvantage: The role of parenting in associations with internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22:335–343. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9582-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice F, Harold GT, Thapar A. Negative life events as an account of age-related differences in the genetic aetiology of depression in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44:977–987. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander JB, McCarty CA. Youth depression in the family context: Familial risk factors and models of treatment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2005;8:203–219. doi: 10.1007/s10567-005-6666-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL. Breaking up is hard to do: The heartbreak of dichotomizing continuous data. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;47:262–266. doi: 10.1177/070674370204700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompson MC, Pierre CB, Haber FM, Fogler JM, Groff AR, Asarnow JR. Family-focused treatment for childhood-onset depressive disorders: Results of an open trial. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;12:403–420. doi: 10.1177/1359104507078474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Rush AJ. Remissions in Maternal Depression and Child Psychopathology: A STARD-Child Report. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Warner V, Wickramaratne P, Moreau D, Olfson M. Offspring of depressed parents: 10 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54:932–940. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830220054009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Nomura Y, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Verdeli H. Offspring of Depressed Parents: 20 Years Later. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1001–1008. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Pilowsky DJ, Poh E, Batten LA, Hernandez M, Stewart JW. Treatment of maternal depression in a medication clinical trial and its effect on children. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2015;172:450–459. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13121679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J, Moore P, Southam-Gerow MA, Weersing VR, Valeri SM, McCarty CA. Therapist's Manual PASCET: Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Training Program. 3rd. Los Angeles, CA: University of California; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Chorpita BF, Palinkas LA, Schoenwald SK, Miranda J, Bearman SK, Gibbons RD. Testing standard and modular designs for psychotherapy treating depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in youth: A randomized effectiveness trial. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69:274–282. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, McCarty CA, Valeri SM. Effects of psychotherapy for depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:132–149. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller EB, Weller RA, Rooney MT, Fristad MA. Children's Interview for Psychiatric Syndomes—Parent Version (P-ChIPS) Arlington, VA US: American Psychiatric Association; 1999a. [Google Scholar]

- Weller EB, Weller RA, Rooney MT, Fristad MA. ChIPS. Arlington, VA US: American Psychiatric Association; 1999b. [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Schry AR, Miyazaki Y, Ollendick TH, Scahill L. Effects of verbal ability and severity of autism on anxiety in adolescents with ASD: One-year follow-up after cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44:839–845. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.893515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Pilowsky DJ, Hughes CW, Garber J, Malloy E, Weissman MM. Children of depressed mothers 1 year after remission of maternal depression: Findings from the STARD-Child study. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:593–602. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]