Abstract

Riemerella anatipestifer (RA), a major causative agent of septicemia anserum exsudativa in domesticated ducklings, has a protein secretion system known as the type IX secretion system (T9SS). It is unknown whether the T9SS contributes to the virulence of RA through secretion of factors associated with pathogenesis. To answer this question, we constructed an RA mutant deficient in sprT, which encodes a core protein of the T9SS. Deletion of sprT yielded cells that failed to digest gelatin, an effect that was rescued via complementation by a plasmid encoding wild-type sprT. Complement-mediated killing was significantly increased in the deletion mutant, suggesting that proteins secreted by the T9SS are necessary for complement evasion in RA. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis revealed that RAYM_01812 and RAYM_04099 proteins containing a subtilisin-like serine protease domain and exhibiting extracellular gelatinase activity were secreted by the T9SS. Animal experiments demonstrated that the virulence of mutant strain ΔsprT strain was attenuated by 42,000-fold relative to wild-type RA-YM. Immunization with the ΔsprT protected ducks from challenge with RA-YM, suggesting that the former can be used as a live attenuated vaccine. These results indicate that the T9SS is functional in RA and contributes to its virulence by exporting key proteins. In addition, subtilisin-like serine proteases which are important virulence factors that interact with complement proteins may enable RA to evade immune surveillance in the avian innate immune system.

Keywords: Riemerella anatipestifer, T9SS, sprT, virulence, gelatinase secretion

Introduction

Riemerella anatipestifer (RA) is a Gram-negative, non-spore-forming, rod-shaped bacterium belonging to the genus Riemerella and family Flavobacteriaceae of the phylum Bacteroidetes (Segers et al., 1993). It usually causes septicemia and serum exudate in ducks, geese, turkeys, and various other domestic and wild birds, resulting in serious economic losses worldwide (Sandhu, 2008). To date, 21 serotypes of RA have been identified and no significant cross-protection has been reported (Sandhu and Leister, 1991; Pathanasophon et al., 2002; Sandhu, 2008). Inactivated bacterins have been used in ducks to prevent RA infection. Live avirulent strains induce longer-lasting protection and are more convenient; however, there are few reports on attenuated live vaccines (Sandhu, 1991; Higgins et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2013). Chemotherapy is the most widely used approach for treating RA infection, but the increasing incidence of drug resistance (Yang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2016) compels the search for new strategies for controlling this disease.

Recently, a novel protein secretion system known as the T9SS or Por secretion system associated with gliding motility and secretion of virulence factors was discovered in many species of Bacteroidetes (Sato et al., 2010; Mcbride and Zhu, 2013; Ksiazek et al., 2015b; Abby et al., 2016; Lasica et al., 2017). The T9SS has been studied in the motile Flavobacterium johnsoniae as well as in the non-motile Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythia, the latter being the major causative agents of periodontitis. The core set of T9SS genes includes gldK, gldL, gldM, gldN, sprA, sprE, and sprT in F. johnsoniae and their orthologs porK, porL, porM, porN, sov, porW, and porT in P. gingivalis. Deletion of some components of the T9SS resulted in protein secretion defects (Rhodes et al., 2010, 2011; Sato et al., 2010; Shrivastava et al., 2013; Veith et al., 2013). Proteins secreted by the T9SS have an N-terminal signal peptide that enables transit across the cytoplasmic membrane via the Sec system, as well as a conserved CTD that is thought to target the proteins to the T9SS (Sato et al., 2010; Slakeski et al., 2011; Glew et al., 2012; Mcbride and Zhu, 2013). Genes encoding T9SS protein orthologs to those in F. johnsoniae and in P. gingivalis have been identified in the genome of RA strain RA-YM (RAYM_04711, RAYM_04706, RAYM_04701, RAYM_04696, RAYM_09602, RAYM_03704, and RAYM_03924) (Zhou et al., 2011). Although the pathogenicity of bacteria is closely related to protein secretion systems, it is unknown whether the T9SS contributes to RA virulence through the secretion of factors associated with pathogenesis or the stress response.

The T9SS component SprT is predicted to be a membrane-associated protein (Sato et al., 2005; Nguyen et al., 2009; Shrivastava et al., 2013). SprT is involved in gliding motility, extracellular chitinase activity, and localization of SprB adhesin in F. johnsoniae (Rhodes et al., 2010; Sato et al., 2010). PorT, orthologs to SprT, is essential for the secretion of gingipains in P. gingivalis (Sato et al., 2005, 2010; Nguyen et al., 2009). A previous study reported that sprT expression was regulated by the iron and ferric uptake regulator Fur, suggesting that the role of SprT protein is to ensure cell survival and fitness by providing transportation to proteins under iron-restricted conditions (Guo et al., 2017). To date, there have been no reports on the T9SS of RA. In this study, we constructed the sprT (RAYM_03924) gene deletion mutant ΔsprT and the complemented strain CΔsprT to investigate the relationship between the T9SS and the biological characteristics and virulence of RA.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Culture Conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. RA-YM was isolated and deposited at the Department of Veterinary Microbiology and Immunology of Huazhong Agricultural University. RA strains were grown on TSA (Difco, Detroit, MI, United States) or TSB (Difco) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Escherichia coli was grown at 37°C on a Luria-Bertani plate or in Luria-Bertani broth. Antibiotic concentrations were as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg/mL; chloramphenicol, 50 μg/mL; spectinomycin (Spc), 100 μg/mL; and diaminopimelic acid, 50 μg/mL.

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study.

| Strains, plasmids, and primers | Descriptions | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| RA-YM | Riemerella anatipestifer wild-type strain, serotype 1 | Preserved in the laboratory |

| ΔsprT | sprT gene deletion mutant strain, SpcR | This study |

| CΔsprT | Complemented RA-YM aaasprT strain, SpcR, AmpR | This study |

| E. coli DH5α | Competent cell | Transgen |

| E. coli X7213 | Competent cell | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMD18-T | TA cloning vector | Takara |

| pRE112 | Suicide vector | Preserved in the laboratory |

| pRE112-LSR | Suicide vector | This study |

| pRES-JX-bla | Shuttle vector | Preserved in the laboratory |

| RA-JX | Wild type plasmid of RA | Preserved in the laboratory |

| pRES-JX-bla-sprT | Shuttle vector | This study |

| pGEX-6P-1 | Expression vector | Preserved in the laboratory |

| pGEX-6P-1_01812 | Expression vector | This study |

| Primers (5′–3′) | ||

| Spc-F1 | CAGTGGAACGAAAACTCACGTT | This study |

| Spc-R1 | CAGTAGTTTTAAAAGTAAGCACCTG | This study |

| SprT-F1 | ACGGGTACCAGGTACTAAAGCCGAAAT | This study |

| SprT-R1 | ACGTGAGTTTTCGTTCCACTGCATGG CAGAAATACTAATG | This study |

| SprT-F2 | TGCTTACTTTTAAAACTACTATACAC GCTGATAGATGG | This study |

| SprT-R2 | CGAGCTCCAAACCTCGGTAAACAAA | This study |

| SprT-IS | ATGGACAGAATGGAAGGC | This study |

| SprT-IR | TTTTGGAGTGAATGGAGC | This study |

| Promoter-sprT1 | GGGTACCAAGTATTTTGGATAAATTAGACT | This study |

| Promoter-sprT2 | TATCTTTTTCATTAATCTTAAAAATTTACAGCCAC | This study |

| SprT-CF | TTTTTAAGATTAATGAAAAAGATATTTTTTTTAAC | This study |

| SprT-CR | GGCATGCTTATTCAAATTTTAGCACAAACA | This study |

| P01812-1 | CGGGATCCATGGCTCAAAACCAAAACACATC | This study |

| P01812-2 | CCCTCGAGCTTCTTGATAAATTTCTTAGTAA | This study |

RResistance.

Construction of Mutant Strain ΔsprT and Complemented Strain CΔsprT

The mutant strain ΔsprT was constructed by allelic exchange using the recombinant suicide plasmid pRE112. Briefly, a 585-bp left flanking region of the sprT gene (Leftarm) was amplified from RA-YM genomic DNA using primers SprT-F1 (introducing a KpnI site) and SprT-R1. A 1086-bp SpcR cassette was amplified from plasmid pIC333 using primers Spc-F and Spc-R. A 867-bp right flanking region of sprT gene (Rightarm) was amplified from RA-YM genomic DNA using primers SprT-F2 and SprT-R2 (introducing a SacI site). The left flanking region, SpcR cassette, and right flanking region were fused by overlap extension PCR using SprT-F1 and SprT-R2. The fused DNA fragment was inserted into pMD18-T to generate pMD18T-Leftarm-Spc-Rightarm, which was digested along with the pRE112 plasmid with KpnI and SacI to obtain the recombinant suicide plasmid pRE112-Leftarm-Spc-Rightarm (pRE112-LSR). This was transformed into E. coli X 7213. The transformants were used as the donor strain in conjugal transfer. The mutant strain was selected on TSA containing 100 μg/mL Spc. The sprT gene deletion mutant strain (ΔsprT) was confirmed by PCR.

The shuttle plasmid pRES-JX-bla was constructed as previously described (Guo et al., 2017) by adding the putative replication region of the RA plasmid RA-JX to the suicide vector. The promoter and coding sequences of sprT were amplified using primers Promoter-sprT1 (introducing a KpnI site) and Promoter-sprT2, SprT-CF, and SprT-CR (introducing a SphI site). The promoter and coding fragments were joined by overlap extension PCR. The product was digested with KpnI and SphI and inserted into pRES-JX-bla to generate plasmid pRES-JX-bla-sprT, which was transferred by conjugation into the mutant strain RA-YMΔsprT. Transconjugants were screened on TSA supplemented with ampicillin and verified by PCR.

Biochemical Characterization of Mutant Strain ΔsprT and Complemented Strain CΔsprT

Growth curves were generated for mutant strain ΔsprT, complemented strain CΔsprT, and wild-type strain RA-YM to determine whether sprT deletion influenced bacterial growth. The three strains were grown for about 48 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 on TSA plates and were inoculated into TSB. At mid-exponential phase, the culture was diluted with fresh medium to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0, and equal amounts of each bacterial culture were transferred to fresh TSB medium at a ratio of 1:1000 (v/v) and cultured at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. OD600 was measured at 1 h intervals for 20 h using a spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States).

Biochemical testing of the three strains was carried out using bacterial biochemical tubes (Hope Bio, Qingdao, China) with glucose, arabinose, sucrose, citrate, hydrogen sulfide, nitrate, carbamide, and gelatin. To visually characterize the presence of liquefied gelatin, RA-YM, ΔsprT, and CΔsprT cells were inoculated into TSB overnight. Cultures (5 μL) were spotted on nutrient gelatin plates and cultivated at 37°C for 24 h. Then, 2–3 mL acid mercuric chloride was added to the plates and color development was assessed after 5 min. Cells capable of liquefying gelatin, were identified by a transparent halo around the bacterial lawn (Frazier, 1926; Mcdade and Weaver, 1959; Thomas et al., 2014).

Serum Survival Assay

Blood was drawn from 12 healthy 30-day-old Cherry Valley ducks without anti-RA antibody and immediately placed on ice. After 2 h, the clotted blood was centrifuged at 2000 × g and 4°C for 10 min. The serum was collected as normal duck serum and stored at -80°C until use.

For the serum survival assay, mutant strain ΔsprT, complemented strain CΔsprT, and wild-type strain RA-YM were cultured in TSB to an OD600 of 0.8. The cells were washed and resuspended to 106 CFU/mL in HBSS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, United States) with 0.15 mM calcium and 1 mM magnesium (HBSS++). After incubation at 37°C for 30 min with or without duck serum, 10-fold serial dilutions of the mixture were spread onto TSA plates. Colonies were counted after incubation for 48 h. The serum survival assay was performed with bacteria resuspended in HBSS++ to prevent replication so that the viability of all strains could be evaluated (Rosadini et al., 2013). The reaction was also performed in the presence or absence of 10 mM Mg2+ EGTA to block the classical complement and lectin pathways and selectively activate the alternative complement pathway. Heat-inactivated serum used in this assay was generated by incubating normal duck serum at 56°C for 30 min. The survival rate was calculated as follows: (number of cells that survived serum treatment/number of cells that survived control treatment) × 100%. Differences among groups were evaluated by analysis of variance using SPSS v.18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean, and statistical significance was determined with the Student’s t-test. A P-value of <0.05 was defined as statistically significant, and P-value of <0.01 was defined as extremely significant.

Gelatin Enzyme Spectrum Assay

Gelatin zymography was used to evaluate the difference in gelatinase secretion between mutant strain ΔsprT, CΔsprT and wild-type strain RA-YM as previously described (Pickett et al., 1991; Toth and Fridman, 2001). Briefly, cells were grown to mid-log phase in TSB at 37°C with shaking, then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min. The culture medium was passed through a 0.22 μm polyvinylidene difluoride filter to remove residual cells, and the supernatant was precipitated with 70% (v/v) saturated ammonium sulfate solution. The precipitate was dissolved with phosphate buffer and samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel copolymerized with gelatin (1%) as the substrate at 4°C. The gel was washed for 2 min, proteins were renatured by incubation for 1 h at room temperature in 2.5% Triton X-100 solution, and then incubated at 37°C for 18–20 h in 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 5 mmol/L CaCl2. The gel was stained with 0.05% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 and then destained with 30% methanol and 10% acetic acid. Gelatinolytic activity was detected as unstained bands against the background of Coomassie-stained gelatin.

Liquid Chromatography Electrospray Ionization Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) Analysis

To detect proteins involved in gelatin hydrolysis, bands that differed between the RA-YM and ΔsprT gels were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. The bands were excised and digested overnight in 12.5 ng/μL trypsin in 25 mM NH4HCO3. The peptides were extracted three times with 60% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, and the extracts were pooled and dried completely in a vacuum centrifuge.

Experiments were performed on a Q Exactive mass spectrometer coupled to Easy nLC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). A 6 μL volume of each fraction was injected for nanoLC-MS/MS analysis. The peptide mixture (5 μg) was loaded onto a C18 reversed-phase Easy Column (length, 10 cm; inner diameter, 75 μm; and 3 μm resin) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in buffer A (0.1% formic acid) and separated with a linear gradient of buffer B (80% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid) at a flow rate of 250 nL/min controlled by IntelliFlow technology over 140 min. MS data were acquired using a data-dependent top 10 method by dynamically selecting the most abundant precursor ions from the survey scan (300–1800 m/z) for higher-energy collisional dissociation fragmentation. Determination of the target value was based on predictive Automatic Gain Control. The duration of dynamic exclusion was 60 s. Survey scans were acquired at a resolution of 70,000 at m/z 200, and the resolution for HCD spectra was set to 17,500 at m/z 200. Normalized collision energy was 30 eV and the underfill ratio, which specifies the minimum percentage of the target value likely to be reached at maximum fill time, was defined as 0.1%. The instrument was run with peptide recognition mode enabled.

MS/MS spectra were searched using MASCOT engine v.2.2 (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom) against the non-redundant International Protein Index Arabidopsis sequence database v.3.85 (released September 2011; 39,679 sequences) from the European Bioinformatics Institute1. The following options were used for protein identification: peptide mass tolerance = 20 ppm, MS/MS tolerance = 0.1 Da, enzyme = trypsin, missed cleavage = 2, fixed modification: carbamidomethyl (C); and variable modification: oxidation (M).

Expression and Purification of Recombinant RAYM_01812 Protein and Zymography

The coding sequence of the RAYM_01812 gene (without the signal peptide) was amplified using primers P01812-1 (introducing a BamHI site) and P01812-2 (introducing an XhoI site). The amplified fragment and vector pGEX-6P-1 were digested with BamHI and XhoI and ligated to generate the expression vector pGEX-6P-1_01812, which was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3). Recombinant RAYM_01812 protein was purified as previously described (Ksiazek et al., 2015a). Transformed E. coli was grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.8, and isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.2 mM. After cultivation at 25°C for 6 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in sodium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH7.5). Cells were disrupted twice in a French press at 100 MPa. After centrifugation at 6000 × g and 4°C for 15 min, the supernatant was separated from the cell pellet and filtered through a 0.45 μm pore size polyvinylidene difluoride membrane to remove residual cell debris. The protein fraction in the supernatant was purified using an ÄKTA purifier instrument and GST Trap HP crude affinity chromatography column (GST Trap FF, GE, China). The protein was eluted using Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.0) containing 10 mM reduced glutathione. The purified RAYM_01812 protein was incubated at 37°C for 0.5, 1, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h. Protein purity was evaluated by 12% SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

Gelatin zymography of the purified RAYM_01812 protein was performed as previously described (Ksiazek et al., 2015a). The protein was incubated at 37°C for 0.5, 1, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h, then mixed with non-reducing SDS sample buffer (1:1) and incubated at 20°C for 15 min. The mixture was resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE on gels containing gelatin at a final concentration of 1 mg/mL at 4°C. The following operations were analogous to those performed in the gelatin enzyme spectrum experiment. Gelatinolytic activity was visible unstained zones against a blue background.

Evaluation of Virulence of Mutant Strain ΔsprT and Complemented Strain CΔsprT in Vivo

Cherry Valley ducklings (10 days old) were obtained from Chunjiang Duck Farm (Wuhan, China) and allowed to adapt to the environment under controlled temperature (30°C) for 2 days. The ducklings had free access to food and water. The experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Experiment Committee of the Veterinary Faculty of Huazhong Agriculture University.

Ducklings (12 days old) were randomly divided into 18 groups (n = 10 per group) and challenged by intramuscular injection of bacteria at 1.0 × 104, 1.0 × 105, 1.0 × 106, 1.0 × 107, 1.0 × 108, or 1.0 × 109 CFU of mutant strain ΔsprT, complemented strain CΔsprT, or wild-type strain RA-YM. The mortality of the ducklings was monitored for 1 week post infection. The LD50 was calculated using an improved Karber’s method (Irwin and Cheeseman, 1939).

To evaluate bacterial invasion into organs, we compared bacterial load in the blood and target organs (spleen, liver, heart, and brain) and examined pathological lesions. Cherry Valley ducklings (12 days old) were randomly divided into two groups (n = 15 per group) and injected intramuscularly with 1 × 107 CFU bacteria (ΔsprT or RA-YM). The organs and blood were collected 24 or 48 h post infection and diluted appropriately. Colonies were counted with the plate pouring method. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean, and statistical significance was determined with the Student’s t-test. A P-value of <0.05 was defined as statistically significant, and P-value of <0.01 was defined as extremely significant. Spleen, liver, heart, and brain tissue sections were immersed in 10% formalin solution for histopathological analyses.

Vaccination and Challenge Studies

Cherry Valley ducklings (7 days old) were randomly divided into five groups (n = 20 per group). Groups 1–3 received a single injection of the mutant strain ΔsprT at doses of 4 × 105, 2 × 106, or 1 × 107 CFU. Group 4 was injected with phosphate-buffered saline. Group 5 was injected with trivalent RA oil-inactivated vaccine at the recommended dose (1 × 1010 CFU/mL, 0.5 mL) (Tianbang, Chengdu, China). Groups 4 and 5 were served as negative and positive controls, respectively. On day 14 post-immunization, the ducks in each group were injected with 2 LD50 or 10 LD50 of RA-YM to evaluate the level of protection conferred by ΔsprT. The protection rate was calculated using the following formula: [1 - (dead ducklings per group/total ducklings per group)] × 100.

Results

Construction and Characterization of Mutant Strain ΔsprT and Complemented Strain CΔsprT

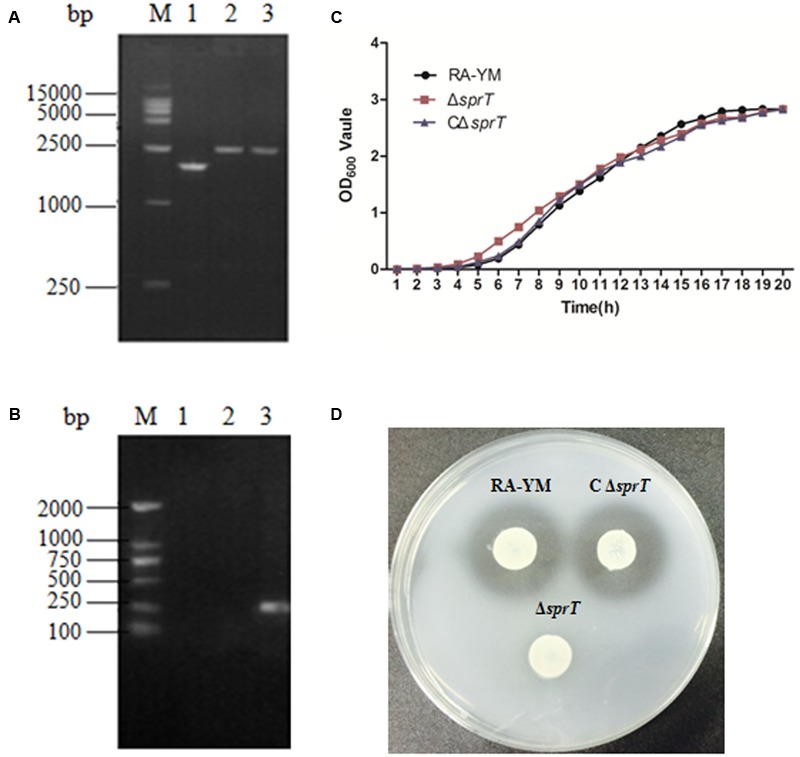

The deletion of the sprT gene after allelic exchange was confirmed by PCR amplification of the smaller fragment (1752-bp) in RA-YM as compared to the larger Leftarm-Spc-Rightarm fragment (2538-bp) in RA-YMΔsprT (Figure 1A). The deleted part of the sprT gene (300-bp) was not detected (Figure 1B). The identity of the complemented strain was also confirmed by PCR.

FIGURE 1.

Identification and characterization of mutant strain ΔsprT and complemented strain CΔsprT. (A) PCR amplification of mutant strain ΔsprT and wild-type strain RA-YM using primers SprT-F1 and SprT-R2. Lane M: DL2000 DNA marker; lane 1: Leftarm-Rightarm DNA fragment (1752-bp) from the wild type; lane 2: Leftarm-Spc-Rightarm DNA fragment (2538-bp) from ΔsprT; lane 3: pRE-LSR (positive control; 2538-bp). (B) PCR amplification of the deleted part of the sprT gene using primers SprT-IS and SprT-IR. Lane M: DL2000 DNA marker; lane 1: pRE-LSR (positive control) no fragment was amplified; lane 2: ΔsprT—no fragment was amplified; lane 3: RA-YM (300-bp). (C) Growth curves for RA-YM, ΔsprT and CΔsprT. (D) Liquefied gelatin following cultivation of RA-YM, ΔsprT, and CΔsprT on a nutrient gelatin plate.

There were no differences in biological characteristics between wild-type RA-YM, mutant ΔsprT, and complemented CΔsprT strains except in the early logarithmic growth phase, with ΔsprT exhibiting more rapid growth as compared to RA-YM, which had a similar growth rate as CΔsprT (Figure 1C). In biochemical tests, there was no difference among ΔsprT, RA-YM, and CΔsprT except in terms of gelatin liquefaction. All three strains showed negative test results for glucose, arabinose, sucrose, citrate, hydrogen sulfide, nitrate, and carbamide. RA-YM and CΔsprT were able to liquefy gelatin whereas ΔsprT was not. The capacity of different strains to liquefy gelatin on nutrient gelatin plates was in accordance with the results of biochemical tests. As shown in Figure 1D, there were transparent zones around RA-YM and CΔsprT, but not around ΔsprT, demonstrating that RA-YM and CΔsprT were able to liquefy gelatin whereas ΔsprT was not.

ΔsprT Mutant Exhibit Increased Sensitivity to Killing by Duck Serum

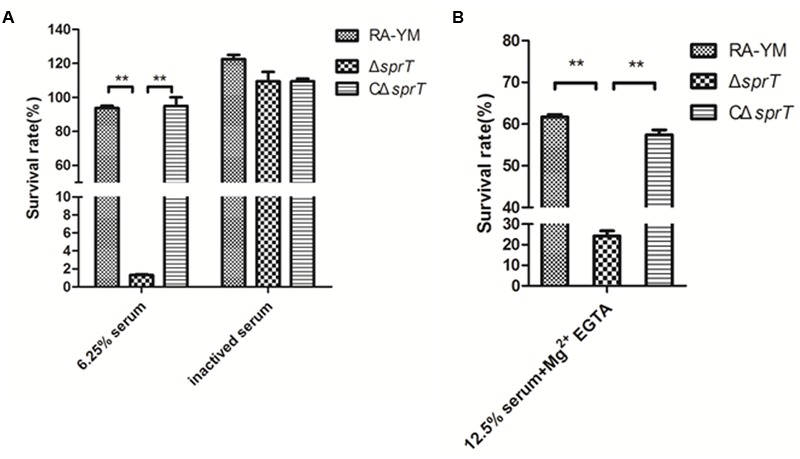

The serum survival assay was carried out to ascertain the ability of the mutant strain ΔsprT to resist complement-mediated killing as compared to the wild-type strain RA-YM. To exclude potential effects of variable growth rates among strains, the assay was performed with the cells resuspended in HBSS++, which prevents replication without affecting viability (data not shown). A range of serum concentrations was evaluated for wild-type strain RA-YM; the survival rate of RA-YM was 93.8% in 6.25% normal duck serum. In contrast, the survival rate of ΔsprT was 1.3% in 6.25% normal duck serum, whereas that of complemented strain CΔsprT was 95% in 6.25% normal duck serum, which was comparable to the wild-type value (Figure 2A). Heat inactivation abrogated the bactericidal effect of serum in ΔsprT, consistent with complement-mediated killing. Together, these results indicate that the T9SS is required for complement resistance in wild-type RA cells.

FIGURE 2.

Serum survival of wild-type strain RA-YM, mutant strain ΔsprT, and complemented strain CΔsprT. (A) Effect of sprT mutation on resistance of RA to duck serum. Strains were treated with 6.25% normal duck serum for 30 min at 37°C and plated for survival analysis. (B) Effect of sprT mutation on resistance of RA to alternative complement pathway-mediated killing. Cells were treated with 12.5% normal duck serum in the presence of Mg2+ EGTA for 30 min at 37°C and plated for survival analysis. Data were analyzed with Student’s t-test (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01).

The ΔsprT mutants were examined for their sensitivity to alternative complement pathway activation. Strains were treated with normal duck serum in buffer in the presence or absence of 10 mM Mg2+ EGTA, which inhibits classical/mannose-binding lectin pathway activation, and then examined for survival. Incubation with Mg2+ EGTA-containing buffer alone did not affect the viability of any of the strains (data not shown). When cells were incubated in 12.5% normal duck serum in the presence of Mg2+ EGTA, the survival rates of RA-YM ΔsprT, and CΔsprT were 61.7, 24.3, and 57.4%, respectively (Figure 2B). Taken together, these data indicate that the proteins secreted by T9SS suppress the alternative complement pathway in RA, possibly by binding factor H.

Gelatin Zymography Assay and LC–MS/MS Analysis

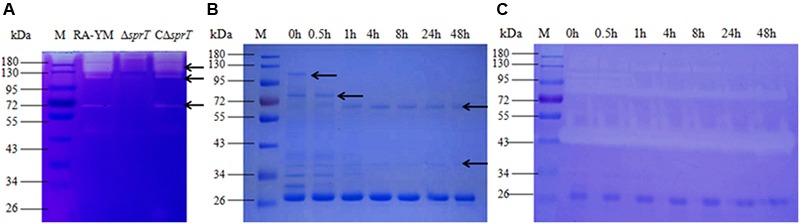

A gelatin zymography assay was performed to compare gelatinase secretion between mutant strain ΔsprT and wild-type strain RA-YM (Figure 3A). Distinct bands in the RA-YM culture supernatant were excised and analyzed by MS. The raw data were converted to XML files for an MS/MS ion search using Mascot and were assigned to the protein sequences of RA (strain ATCC 11845/DSM 15868/JCM 9532/NCTC 11014), as annotated by the Uniprot database. Positive hits were accepted with a Mascot score of at least 20. A total of 52 proteins were identified (Supplementary Table S1). T9SS proteins were predicted by running a Function Search analysis of the conserved CTDs of the TIGRfam families TIGR04131 and TIGR04183 (Sato et al., 2013; Kharade and McBride, 2014).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Gelatin zymography assay of wild-type strain RA-YM, mutant strain ΔsprT, and complemented strain CΔsprT. Regions of clearing reflect protease activity. Black arrows indicate distinct protease activity present in RA-YM and ΔsprT. These bands were excised for identification by MS. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinant RAYM_01812 protein incubated at 37°C for different times. M: protein marker; lane 1: purified GST-RAYM_01812 fusion protein; lanes 2–7: purified GST-RAYM_01812 fusion protein incubated at 37°C for 0.5 h (lane 2), 1 h (lane 3), 4 h (lane 4), 8 h (lane 5), 24 h (lane 6), and 48 h (lane 7). (C) Ability of purified RAYM_01812 protein to degrade gelatin after incubation at 37°C for different times. M: protein marker; lane 1: purified GST-RAYM_01812 fusion protein; lanes 2–7: gelatin zymography analysis of GST-01812 fusion protein incubated at 37°C for 0.5 h (lane 2), 1 h (lane 3), 4 h (lane 4), 8 h (lane 5), 24 h (lane 6), and 48 h (lane 7).

Among the 52 proteins, seven had CTDs belonging to TIGR04183 or TIGR04131, and may therefore be secreted by the T9SS (Table 2). RAYM_09380 and RAYM_02622 were hypothetical proteins and RAYM_05530 had a periplasmic ligand-binding sensor domain related to signal transduction. The four other proteins all had a Por_Secre_tail, but their functions differed according to their specific structural domains. RAYM_08375, containing a polycystic kidney disease (PKD) and two Sialidase_non-viral domains, was predicted to encode glycosyl hydrolase. RAYM_04099, containing a Peptidases_S8_Kp43_protease domain, encodes peptidase S8/S53 subtilisin kexin sedolisin. RAYM_03382, containing a metallophosphatase superfamily and calcineurin-like phosphoesterase domains, was predicted to encode phosphohydrolases. RAYM_01812, also containing Peptidases_S8_S53 superfamily and peptidase_S8 domains, encodes a subtilisin-like serine protease.

Table 2.

C-terminal domains (CTDs) of proteins identified in zymogram gels of RA-YM.

| Locus tag | Description | MW (KDa) | CTD present | TIGRfam |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAYM_09380 | Hypothetical protein | 131.7 | + | TIGR04131 |

| RAYM_03382 | Phosphohydrolases | 68.2 | + | TIGR04183 |

| RAYM_04099 | Subtilisin-like serine protease | 161.5 | + | TIGR04183 |

| RAYM_08375 | Glycosyl hydrolase | 117.3 | + | TIGR04183 |

| RAYM_01812 | Subtilisin-like serine protease | 62.3/77.8 | + | TIGR04183 |

| RAYM_05530 | Immunoreactive 84 kDa antigen PG93 | 83.1 | + | TIGR04183 |

| RAYM_02622 | Hypothetical protein | 117.1 | + | TIGR04183 |

RAYM_01812 was expressed as a fusion protein with a molecular mass of 102 kDa and the capacity for autoproteolytic cleavage (Figure 3B). The full-length recombinant RAYM_01812 protein (without GST label) had a mass of 76 kDa. Following removal of the NTP, preCTD and CTD regions, the active protease comprising only CD regions was left with a molecular mass of 38 kDa. Gelatin zymography analysis of purified RAYM_01812 revealed that three forms of the protein were capable of degrading gelatin (Figure 3C).

Virulence of Mutant Strain ΔsprT and Complemented Strain CΔsprT in Vivo

The LD50 for the mutant strain ΔsprT was 1.61 × 109 CFU, which was 4.21 × 104-fold lower than that of the parent strain RA-YM (3.82 × 104 CFU) and of CΔsprT (4.37 × 104 CFU). This indicated that the virulence of ΔsprT was potently suppressed, an effect that was rescued by complementation. Since the difference between RA-YM and CΔsprT was negligible, in subsequent experiments we compared only RA-YM and ΔsprT.

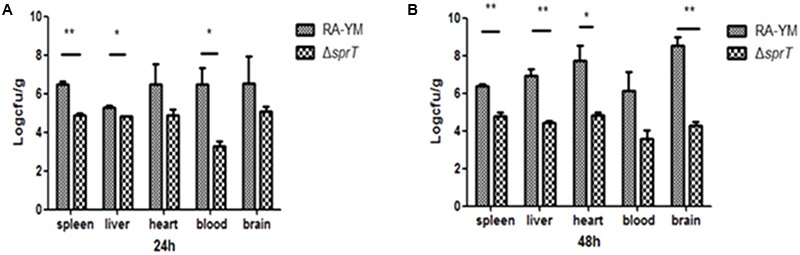

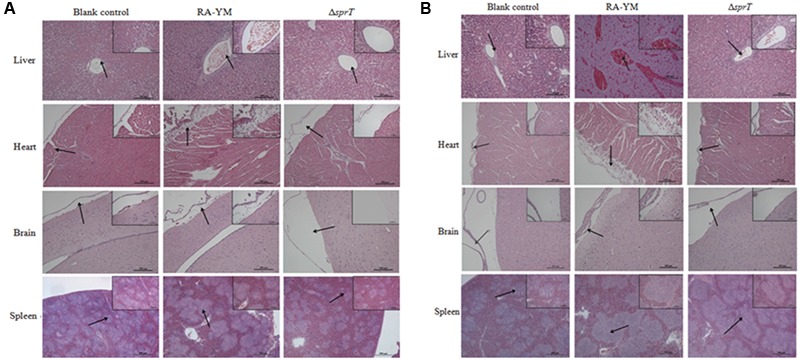

To examine the invasiveness of the bacteria in greater detail, bacterial load in the blood, spleen, liver, heart, and brain was quantified. The bacterial burden of ΔsprT in the blood, spleen, and liver was much lower than that of RA-YM at 24 and 48 h post challenge (Figure 4). We also compared tissue damage caused by RA-YM and ΔsprT. In the RA-YM group, there was obvious congestion in the hepatic sinusoid and central vein, fatty degeneration of hepatocytes, a large quantity epicardial fibrin exudate, and inflammatory cells; notably, the latter two were present also in the subarachnoid space. Additionally, lymphocyte proliferation of splenic white pulp was also observed. This phenotype was greatly attenuated in the ΔsprT and negative control groups at 24 h (Figure 5A) and 48 h (Figure 5B) post challenge.

FIGURE 4.

Bacterial load in blood and organs of ducklings infected with wild-type strain RA-YM or mutant strain ΔsprT. Tissue burden in groups infected with RA-YM or ΔsprT 24 h (A) and 48 h (B) post challenge. Data represent mean ± standard deviation of five animals. Data were analyzed with Student’s t-test (∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01).

FIGURE 5.

Histopathological analysis of ducklings infected with wild-type strain RA-YM or mutant strain ΔsprT. Tissue specimens were analyzed 24 h (A) and 48 h (B) post challenge.

Protective Effect of Vaccination with Mutant Strain ΔsprT against Virulent RA-YM

Finally, we evaluated whether the mutant strain ΔsprT could be used as a live attenuated vaccine. Ducks were administered 2 LD50 and 10 LD50 of virulent RA-YM by intramuscular injection 14 days after vaccination. At 24 h post-injection, clinical symptoms and death were observed in Group 4, whereas ducks in Groups 1–3 that were vaccinated with ΔsprT showed only mild symptoms. When ΔsprT was injected at a dose of 1 × 107 CFU per duck (Group 3), immune protective ratios were 100 and 88.9% as compared to 80 and 70%, respectively, in the vaccine group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Immune effect of the mutant strain ΔsprT.

| Group | Inoculation type | Survival of ducks/total ducks |

Protection rates (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 LD50 | 10 LD50 | 2 LD50 | 10 LD50 | ||

| 1 | ΔsprT (4 × 105 CFU) | 6/10 | 7/10 | 60 | 70 |

| 2 | ΔsprT (2 × 106 CFU) | 8/10 | 6/8 | 80 | 75 |

| 3 | ΔsprT (1 × 107 CFU) | 9/9 | 8/9 | 100 | 88.9 |

| 4 | PBS (negative control) | 1/10 | 0/10 | 10 | 0 |

| 5 | Oil-inactivated vaccine (5 × 109 CFU) | 8/10 | 7/10 | 80 | 70 |

Discussion

Specialized protein secretion systems in many pathogenic bacteria comprise virulence mechanisms for the secretion of extracellular enzymes, proteases, and virulence factors that destroy host cells and cause tissue necrosis. Eight such systems have been identified to date in Gram-negative bacteria (Economou et al., 2006). T1SS, T3SS, T4SS, and T6SS transport proteins from the cytoplasm across both membranes of the cell, whereas T2SS, T5SS, T8SS (the extracellular nucleation-precipitation pathway involved in curli biogenesis), and the chaperone-usher pathway (involved in pilus assembly) facilitate secretion across the outer membrane only. T9SS, which is also known as Por secretion system, is present in most genera and species of the phylum Bacteroidetes, including F. johnsoniae, P. gingivalis, T. forsythia, and the poultry pathogen RA (Mcbride and Zhu, 2013). P. gingivalis T9SS is involved in the secretion of virulence factors, such as Arg-gingipain, Lys-gingipain, and Skp-protein, which damage human tissues and dysregulate the immune response (Nakayama et al., 1995; Shi et al., 1999; Sato et al., 2013; Taguchi et al., 2015). T. forsythia also uses this pathway to disseminate proteins, such as KLIKK proteases (Narita et al., 2014; Ksiazek et al., 2015b). In this study, the virulence of the mutant strain ΔsprT was attenuated by more than 42,000-fold and bacterial load in the blood, spleen, brain, heart, and liver of ducks infected with ΔsprT were significantly reduced as compared to those of RA-YM-infected ducks. Moreover, this tendency was confirmed by histopathological results. Thus, our findings confirm that T9SS plays a critical role in the pathogenicity of RA. We also show that ΔsprT administration effectively protected the ducks from challenge with virulent RA-YM strains, suggesting that the mutant strain can be used as an attenuated vaccine target or live vaccine vector for controlling septicemia anserum exsudativa in ducks.

Bacterial virulence factors are secreted proteins that have pathogenic effects. PorT was reported to be involved in the secretion of gingipains and the mutant showed decreased Arg- and Lys-gingipains activities in both the whole-cell and supernatant fractions (Sato et al., 2005; Nguyen et al., 2009). Deleting porT in T. forsythia results in the lack of an S-layer, which functions as a protective coat, external sieve, and ion trap (Narita et al., 2014; Tomek et al., 2014). The F. johnsoniae sprT mutant is defective in extracellular chitinase activity (Sato et al., 2010). In RA, deletion of sprT yielded cells that failed to liquefy gelatin; this phenotype was rescued by complementation with wild-type sprT.

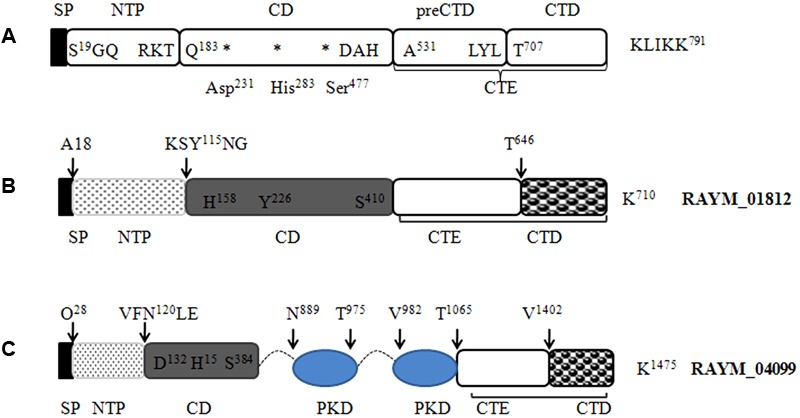

Our LC-MS/MS analysis revealed that RAYM_01812 and RAYM_04099 were secreted by the T9SS. A comparison of their sequences revealed a domain structure that included a typical N-terminal signal peptide, subtilisin-like protease catalytic domain and C-terminal extension (Figure 6) (Ksiazek et al., 2015a). RAYM_01812 and RAYM_04099 showed 32 and 20% identity with T. forsythia mirolase, a subtilisin-like serine protease (Ksiazek et al., 2015a); and 34 and 40% identity with Pseudoalteromonas sp. SM9913 deseasin MCP-01, a collagenolytic, cold-adapted serine protease (Chen et al., 2007). The PKD domain of RAYM_04099 was reported to be a collagen-binding domain that could improve the collagenolytic efficiency of the catalytic domain (Wang et al., 2010). These results indicate that RAYM_01812 and RAYM_04099 encode serine proteases. The conserved catalytic residues of the Peptidases_S8_S53 superfamily domain may be responsible for the hydrolysis of gelatin, which was confirmed for recombinant protein RAYM_01812 by gel electrophoresis and zymography. Gelatinolytic activity is the most significant biochemical property in virulent RA; this is the first report of a protease related to gelatin degradation and of subtilisin-like serine proteases in the culture supernatant of RA. In some Gram-negative bacteria, special proteinases contribute to host invasion (Backert and Meyer, 2006). For instance, gelatinase can degrade host collagen and generate nutrients for the pathogen, thereby enhancing the pathogen’s aggressiveness (Corbel et al., 2002). These proteins are either released into the extracellular matrix or directly injected into host cells (Juhas et al., 2008). Previous studies have shown that in Enterococcus, the gene encoding gelatinase was a virulence factor whose expression could directly influence bacterial pathogenicity (Sifri et al., 2002; Engelbert et al., 2004), and a serine protease known as dentilisin in Treponema denticola has been implicated in complement evasion by C3 cleavage (Yamazaki et al., 2006). Mirolase, a subtilisin-like serine protease, contributes to T. forsythia pathogenicity by degrading fibrinogen, hemoglobin, and the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 (Ksiazek et al., 2015a).

FIGURE 6.

Predicted protein domain structure of the S8 family of serine proteases in RA. Predicted structures of mirolase (A) (Ksiazek et al., 2015a), RAYM_01812 (B), and RAYM_04099 (C). Signal peptides were predicted using the Signal IP 3.0 Server.

To induce bacteremia, pathogenic bacteria must evade serum killing, which is mainly mediated by the complement system. The mechanism of complement resistance in bacteria involves protease digestion of complement components; recruitment of factors such as factor H and C4-binding protein—which inhibit complement activation—to the bacterial cell surface; and polysaccharide-mediated suppression of complement activation. In this study, we showed that SprT protein was required for full serum resistance and for defense against alternative complement pathway activation. Thus, proteins secreted by the T9SS are involved in complement resistance in RA. The ΔsprT mutant is likely defective in the secretion of virulence factors into the extracellular environment or in their expression on the cell surface, which facilitate evasion of complement-mediated killing. Additionally, secreted proteins may directly cleave antibodies and complement components or bind complement-inhibiting molecules; indeed, proteolytic inactivation of the complement system is a common strategy for avoiding host immune surveillance mechanisms. A number of studies have shown that proteolytic enzymes such as T. denticola dentilisin, P. gingivalis gingipains, T. forsythia karilysin, and P. intermedia interpain are primary weapons of defense against host innate immunity. Additional studies are needed to clarify the role of proteinases such as RAYM_01812 that are secreted through the T9SS in the degradation and functional inactivation of host complement components.

In summary, the results presented here demonstrate that the T9SS—which is involved in the secretion of the subtilisin-like proteases RAYM_01812 and RAYM_04099 with extracellular gelatinase activity—is critical for the virulence of RA. Given that the T9SS of RA is involved in serum resistance, we are now working to identify T9SS substrates and verify their roles in evading the complement system, which can provide insight into the virulence mechanism of this pathogen.

Author Contributions

YG and DH wrote the manuscript. Construction of the mutant strain ΔsprT, its virulence, and immune protection were determined by TW. The complemented strain was constructed by YG. The expression of the recombinant protein RAYM_01812 was performed by JG. Gelatin zymography and LC–MS/MS analysis were performed by DH. YX, XW, SL, ML, ZL, and DB designed and participated to the experiments. ZZ designed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31201933) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (no. 52902-0900206127).

Abbreviations

- CFU

Colony-forming units

- CTD

C-terminal domain

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salt solution

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry

- LD50

median lethal dose

- RA

Riemerella anatipestifer

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- T9SS

type IX secretion system

- TSA

tryptic soy agar

- TSB

tryptic soy broth

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02553/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abby S. S., Cury J., Guglielmini J., Néron B., Touchon M., Rocha E. P. C. (2016). Identification of protein secretion systems in bacterial genomes. Sci. Rep. 6:23080. 10.1038/srep23080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S., Meyer T. F. (2006). Type IV secretion systems and their effectors in bacterial pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9 207–217. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Xie B., Lu J., He H., Zhang Y. (2007). A novel type of subtilase from the psychrotolerant bacterium Pseudoalteromonas sp. SM9913: catalytic and structural properties of deseasin MCP-01. Microbiology 153 2116–2125. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006056-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbel M., Belleguic C., Boichot E., Lagente V. (2002). Involvement of gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) in the development of airway inflammation and pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 18 51–61. 10.1023/A:1014471213371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economou A., Christie P. J., Fernandez R. C., Palmer T., Plano G. V., Pugsley A. P. (2006). Secretion by numbers: protein traffic in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 62 308–319. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05377.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbert M., Mylonakis E., Ausubel F. M., Calderwood S. B., Gilmore M. S. (2004). Contribution of gelatinase, serine protease, and fsr to the pathogenesis of Enterococcus faecalis endophthalmitis. Infect. Immun. 72 3628–3633. 10.1128/IAI.72.6.3628-3633.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier W. C. (1926). A method for the detection of changes in gelatin due to bacteria. J. Infect. Dis. 39 302–309. 10.1093/infdis/39.4.302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glew M. D., Veith P. D., Peng B., Chen Y. Y., Gorasia D. G., Yang Q., et al. (2012). PG0026 is the C-terminal signal peptidase of a novel secretion system of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 287 24605–24617. 10.1074/jbc.M112.369223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Hu D., Guo J., Li X., Guo J., Wang X., et al. (2017). The role of the regulator fur in gene regulation and virulence of Riemerella anatipestifer assessed using an unmarked gene deletion system. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7:382. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins D. A., Henry R. R., Kounev Z. V. (2000). Duck immune responses to Riemerella anatipestifer vaccines. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 24 153–167. 10.1016/S0145-305X(99)00070-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin J. O., Cheeseman E. A. (1939). On an approximate method of determining the median effective dose and its error, in the case of a quantal response. J. Hyg. 39 574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhas M., Crook D. W., Hood D. W. (2008). Type IV secretion systems: tools of bacterial horizontal gene transfer and virulence. Cell Microbiol. 10 2377–2386. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01187.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharade S. S., McBride M. J. (2014). Flavobacterium johnsoniae chitinase ChiA is required for chitin utilization and is secreted by the type IX secretion system. J. Bacteriol. 196 961–970. 10.1128/JB.01170-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek M., Karim A. Y., Bryzek D., Enghild J. J., Thøgersen I. B., Koziel J., et al. (2015a). Mirolase, a novel subtilisin-like serine protease from the periodontopathogen Tannerella forsythia. Biol. Chem. 396 261–275. 10.1515/hsz-2014-0256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek M., Mizgalska D., Eick S., Thøgersen I. B., Enghild J. J., Potempa J. (2015b). KLIKK proteases of Tannerella forsythia: putative virulence factors with a unique domain structure. Front. Microbiol. 6:312. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasica A. M., Ksiazek M., Madej M., Potempa J. (2017). The type IX secretion system (T9SS): highlights and recent insights into its structure and function. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7:215. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Jiang H., Xiang R., Sun N., Zhang Y., Zhao L., et al. (2016). Effects of two efflux pump inhibitors on the drug susceptibility of Riemerella anatipestifer isolates from China. J. Integr. Agric. 15 929–933. 10.1016/S2095-3119(15)61031-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Wang X., Ding C., Han X., Cheng A., Wang S., et al. (2013). Development and evaluation of a trivalent Riemerella anatipestifer-inactivated vaccine. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 20 691–697. 10.1128/CVI.00768-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcbride M. J., Zhu Y. (2013). Gliding motility and Por secretion system genes are widespread among members of the phylum Bacteroidetes. J. Bacteriol. 195 270–278. 10.1128/JB.01962-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdade J. J., Weaver R. H. (1959). Rapid methods for the detection of gelatin hydrolysis. J. Bacteriol. 77 60–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K., Kadowaki T., Okamoto K., Yamamoto K. (1995). Construction and characterization of arginine-specific cysteine proteinase (Arg-gingipain)-deficient mutants of Porphyromonas gingivalis Evidence for significant contribution of arg-gingipain to virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 270 23619–23626. 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita Y., Sato K., Yukitake H., Shoji M., Nakane D., Nagano K., et al. (2014). Lack of a surface layer in Tannerella forsythia mutants deficient in the type IX secretion system. Microbiology 160 2295–2303. 10.1099/mic.0.080192-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K. A., Zylicz J., Szczesny P., Sroka A., Hunter N., Potempa J. (2009). Verification of a topology model of PorT as an integral outer-membrane protein in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Microbiology 155 328–337. 10.1099/mic.0.024323-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathanasophon P., Phuektes P., Tanticharoenyos T., Narongsak W., Sawada T. (2002). A potential new serotype of Riemerella anatipestifer isolated from ducks in Thailand. Avian Pathol. 31 267–270. 10.1080/03079450220136576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett M. J., Greenwood J. R., Harvey S. M. (1991). Tests for detecting degradation of gelatin: comparison of five methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29 2322–2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes R. G., Samarasam M. N., Shrivastava A., van Baaren J. M., Pochiraju S., Bollampalli S., et al. (2010). Flavobacterium johnsoniae gldN and gldO are partially redundant genes required for gliding motility and surface localization of SprB. J. Bacteriol. 192 1201–1211. 10.1128/JB.01495-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes R. G., Samarasam M. N., Van Groll E. J., McBride M. J. (2011). Mutations in Flavobacterium johnsoniae sprE result in defects in gliding motility and protein secretion. J. Bacteriol. 193 5322–5327. 10.1128/JB.05480-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosadini C. V., Ram S., Akerley B. J. (2013). Outer membrane protein P5 is required for resistance of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae to both the classical and alternative complement pathways. Infect. Immun. 82 640–649. 10.1128/IAI.01224-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu T. S. (1991). Immunogenicity and safety of a live Pasteurella anatipestifer vaccine in White Pekin ducklings: Laboratory and field trials. Avian Pathol. 20 423–432. 10.1080/03079459108418780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu T. S. (2008). “Riemerella anatipestifer infection,” in Diseases of Poultry 12th Edn eds Saif Y. M., Barnes H. J., Fadly A. M., Glisson J. R., McDougald L. R., Swayne D. E. (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.) 758–764. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu T. S., Leister M. L. (1991). Serotypes of ‘Pasteurella’ anatipestifer isolates from poultry in different countries. Avian Pathol. 20 233–239. 10.1080/03079459108418760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Naito M., Yukitake H., Hirakawa H., Shoji M., McBride M. J., et al. (2010). A protein secretion system linked to bacteroidete gliding motility and pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 276–281. 10.1073/pnas.0912010107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Sakai E., Veith P. D., Shoji M., Kikuchi Y., Yukitake H., et al. (2005). Identification of a new membrane-associated protein that influences transport/maturation of gingipains and adhesins of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Biol. Chem. 280 8668–8677. 10.1074/jbc.M413544200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Yukitake H., Narita Y., Shoji M., Naito M., Nakayama K. (2013). Identification of Porphyromonas gingivalis proteins secreted by the Por secretion system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 338 68–76. 10.1111/1574-6968.12028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segers P., Mannheim W., Vancanneyt M., De Brandt K., Hinz K. H., Kersters K., et al. (1993). Riemerella anatipestifer gen. nov., comb. nov., the causative agent of septicemia anserum exsudativa, and its phylogenetic affiliation within the Flavobacterium-Cytophaga rRNA homology group. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 43 768–776. 10.1099/00207713-43-4-768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Ratnayake D. B., Okamoto K., Abe N., Yamamoto K., Nakayama K. (1999). Genetic analyses of proteolysis, hemoglobin binding, and hemagglutination of Porphyromonas gingivalis Construction of mutants with a combination of rgpA, rgpB, kgp, and hagA. J. Biol. Chem. 274 17955–17960. 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava A., Johnston J. J., van Baaren J. M., McBride M. J. (2013). Flavobacterium johnsoniae GldK, GldL, GldM, and SprA are required for secretion of the cell surface gliding motility adhesins SprB and RemA. J. Bacteriol. 195 3201–3212. 10.1128/JB.00333-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifri C. D., Mylonakis E., Singh K. V., Qin X., Garsin D. A., Murray B. E., et al. (2002). Virulence effect of Enterococcus faecalis protease genes and the quorum-sensing locus fsr in Caenorhabditis elegans and mice. Infect. Immun. 70 5647–5650. 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5647-5650.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slakeski N., Seers C. A., Ng K., Moore C., Cleal S. M., Veith P. D., et al. (2011). C-terminal domain residues important for secretion and attachment of RgpB in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 193 132–142. 10.1128/JB.00773-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi Y., Sato K., Yukitake H., Inoue T., Nakayama M., Naito M., et al. (2015). Involvement of an Skp-like protein, PGN_0300, in the type IX secretion system of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 84 230–240. 10.1128/IAI.01308-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R., Hamat R. A., Neela V. (2014). Extracellular enzyme profiling of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia clinical isolates. Virulence 5 326–330. 10.4161/viru.27724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomek M. B., Neumann L., Nimeth I., Koerdt A., Andesner P., Messner P., et al. (2014). The S-layer proteins of Tannerella forsythia are secreted via a type IX secretion system that is decoupled from protein O-glycosylation. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 29 307–320. 10.1111/omi.12062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth M., Fridman R. (2001). “Assessment of gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9) by gelatin zymography,” in Metastasis Research Protocols. Methods in Molecular Medicine Vol. 57 eds Brooks S. A., Schumacher U. (New York, NY: Humana Press; ) 163–174. 10.1385/1-59259-136-1:163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veith P. D., Nor Muhammad N. A., Dashper S. G., Likić V. A., Gorasia D. G., Chen D., et al. (2013). Protein substrates of a novel secretion system are numerous in the Bacteroidetes phylum and have in common a cleavable C-terminal secretion signal, extensive post-translational modification, and cell-surface attachment. J. Proteome Res. 12 4449–4461. 10.1021/pr400487b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-K., Zhao G.-Y., Li Y., Chen X.-L., Xie B.-B., Su H.-N., et al. (2010). Mechanistic insight into the function of the C-terminal PKD domain of the collagenolytic serine protease deseasin MCP-01 from deep sea Pseudoalteromonas sp. SM9913: binding of the PKD domain to collagen results in collagen swelling but does not unwind the collagen triple helix. J. Biol. Chem. 285 14285–14291. 10.1074/jbc.M109.087023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T., Miyamoto M., Yamada S., Okuda K., Ishihara K. (2006). Surface protease of Treponema denticola hydrolyzes C3 and influences function of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Microbes Infect. 8 1758–1763. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F.-F., Sun Y.-N., Li J.-X., Wang H., Zhao M.-J., Su J., et al. (2012). Detection of aminoglycoside resistance genes in Riemerella anatipestifer isolated from ducks. Vet. Microbiol. 158 451–452. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Peng X., Xiao Y., Wang X., Guo Z., Zhu L., et al. (2011). Genome sequence of poultry pathogen Riemerella anatipestifer strain RA-YM. J. Bacteriol. 193 1284–1285. 10.1128/JB.01445-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.