Abstract

Pineapple (Ananas comosus L.) cultivation commonly relies on asexual reproduction which is easily impeded by many factors in agriculture production. Sexual reproduction might be a novel approach to improve the pineapple planting. However, genes controlling pineapple sexual reproduction are still remain elusive. In different organisms a conserved superfamily proteins known as ATP binding cassette (ABC) participate in various biological processes. Whereas, till today the ABC gene family has not been identified in pineapple. Here 100 ABC genes were identified in the pineapple genome and grouped into eight subfamilies (5 ABCAs, 20 ABCBs, 16 ABCCs, 2 ABCDs, one ABCEs, 5 ABCFs, 42 ABCGs and 9 ABCIs). Gene expression profiling revealed the dynamic expression pattern of ABC gene family in various tissues and different developmental stages. AcABCA5, AcABCB6, AcABCC4, AcABCC7, AcABCC9, AcABCG26, AcABCG38 and AcABCG42 exhibited preferential expression in ovule and stamen. Over-expression of AcABCG38 in the Arabidopsis double mutant abcg1-2abcg16-2 partially restored its pollen abortion defects, indicating that AcABCG38 plays important roles in pollen development. Our study on ABC gene family in pineapple provides useful information for developing sexual pineapple plantation which could be utilized to improve pineapple agricultural production.

Keywords: pineapple, sexual reproduction, ABC genes, expression profile, pollen abortion

Introduction

The ATP-binding cassette (ABC) gene family is one of the largest expressed gene subfamilies (Campa et al., 2008). Most ABC transporter subfamilies had highly conservative amino acid sequence domains: the nucleotide-binding domain (NBDs) and the transmembrane domains (TMDs) including five or six helices (Higgins and Linton, 2004). The NBD provides energy by hydrolyzing ATP, and the TMDs determines the substrate specificity (Schneider and Hunke, 1998). NBDs contains three exceptional motifs: the signature motif, the Walker A motif and the Walker B motif. The signature motif is unique to ABC proteins while the Walker A and Walker B motif are responsible for nucleotide binding (Davidson et al., 2008). ABC transporter proteins have been classified into two categories based on the length of structural domain: full-sized transporters (two NBDs and two TMDs) and half-sized transporters (one NBD) (Davidson et al., 2008). Protein structures were closely associated with function. The ABCE and ABCF subfamilies lack of TMDs domain and do not function as transporter. For example, the first human and mammalian ABC protein ABC50 which does not contain TMDs, were endowed with ribosome assembly (Richard et al., 1998; Tyzack et al., 2000). ABCE (Y39E4B.1) had been reported for regulating transcription and translation in eukaryotes (Zhao et al., 2004).

The majority of ABC family members are involved in transporting a variety of compounds through biological membranes, such as lipids, suberin, steroids, irons, amino acids and other metabolic substances (Klein et al., 1999). Disruption of ABC transporter proteins has huge impact on bacterial physiology such as toxic effect (Henderson and Payne, 1994). The ABC transporters also participated in plant development. In Arabidopsis, auxin regulate almost every biological processes from early embryonic development to leaf senescence (Paponov et al., 2005). AtPGP1 and AtPGP19, two of Arabidopsis multidrug-resistance-like ABC transporters control polar auxin transport and the double mutant atpgp1-1atpgp19-1 exhibits epinastic growth and small inflorescence size (Geisler et al., 2003). It was recently shown that AtABCG1 and AtABCG16 implicated in the integrity of exine and nexine of pollen wall and the formation of pollen-derived intine layer (Yadav and Reed, 2014). The microspores of double mutants abcg1abcg16 exhibit defects in pollen mitosis in postmeiotic stages of male gametophyte development as well as lack of intact nexine and intine pollen layers in Arabidopsis (Yim et al., 2016).

Pineapple (Ananas comosus L.), a perennial monocot from the Bromeliaceae family, is one of the famous tropical and edible flavorful fruits. Pineapple is usually diploid (2n = 50) and the haploid genome size is estimated to be 526 Mb (Arumuganathan and Earle, 1991). In agriculture production, pineapple planting is impeded by abiotic and/or biotic factors, such as cold, fusarium wilt, and other diseases (Pujol and Kado, 2000; Peckham et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014; Santos et al., 2016). In addition, pineapple is one of the self-incompatible species, and cultivated mostly by vegetative propagation. The pineapple varieties resulted by vegetative propagation greatly reduces fruit quality and heterogeneity (Fassinou Hotegni et al., 2015). These disadvantages of asexual cultivation could be effectively improved by sexual propagation. However, sexual propagation through clearing harmful mutations could improve the fruit quality of generations, which was more adaptive to effective evolutionary responses to natural selection (Otto, 2009; Neiman and Schwander, 2011; Levitis et al., 2017). Recent study shows that pollen development is crucial for sexual reproduction in plants and the quantity and quality of pollen received determines pollen limitation (Aizen and Harder, 2007; Rodger and Ellis, 2016). Overall, there is a serous limitation in pineapple vegetative propagation and sexual reproduction could become novel approach to overcome these problems. In view of the widely function were involved in reproduction development for ABC transporter proteins but how AcABC proteins function in pineapple reproduction is unknown, genome-wide identification, characterization and function study of the ABC transporter gene family in pineapple would become very meaningful.

Recently, sequencing and genome assembly of the entire genome of pineapple has been completed (Ming et al., 2015), which made it possible to systematically study of the ABC subfamily in pineapple. In this study, we performed the analyses of gene phylogeny, gene structure, and expression profiles of ABC proteins in different reproductive organs and different developmental stages in pineapple. We provided comprehensive information of ABC proteins in pineapple and determined the critical role of the stamen enriched gene AcABCG38 in pollen development. Present work may contribute to improve pineapple production though sexual reproduction.

Materials and Methods

Identification of ABC Transporter Genes in Pineapple Genome

The AcABC protein and genome sequence were downloaded from Phytozome v12.11. To identify the AcABC genes, the HMMER3.02 was used with default parameters settings to search the proteins sequences containing PFAM ABC domain (PF00005) (Verrier et al., 2008). To achieve accuracy in our analysis, we further used NCBI-CDD with E-value threshold 0.013 to analyze the conservative sequences and to remove any sequences which lack ABC annotation (Zhang et al., 2017). Isoelectric point (PI) and molecular weight (MW) of the AcABC family member proteins were obtained using ExPAsy website4 (Table 1).

Table 1.

The ABC gene family in pineapple.

| Group | Transcipt ID | Gene name | Topology | Ch | Length(aa) | MW(Kd) | pI | Main loca. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subfamily A, 5 members | ||||||||

| AOH | Aco007263.1 | AcABCA1 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG23 | 1885 | 209.74 | 7.28 | fruit.S7 |

| ATH | Aco028137.1 | AcABCA2 | TMD-NBD | scaffold_1582 | 967 | 107.06 | 7.81 | Flower |

| Aco006844.1 | AcABCA3 | TMD-NBD | LG01 | 961 | 106.43 | 6.95 | Stamen.S5 | |

| Aco006845.1 | AcABCA4 | TMD-NBD | LG01 | 890 | 99.17 | 8.62 | Ovule.S7 | |

| Aco014363.1 | AcABCA5 | TMD-NBD | LG05 | 947 | 106.5 | 8.76 | Flower | |

| Subfamily B, 18 members | ||||||||

| MDR | Aco010196.1 | AcABCB1 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG25 | 1252 | 144.98 | 9.32 | Ovule.S1 |

| Aco012952.1 | AcABCB2 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG03 | 1216 | 139.29 | 9.18 | Petal.S3 | |

| Aco027643.1 | AcABCB3 | TMD-NBD-TMD | scaffold_777 | 992 | 107.44 | 8.91 | Root | |

| Aco016500.1 | AcABCB4 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG11 | 1613 | 108.46 | 9.03 | Stamen.S4 | |

| Aco022110.1 | AcABCB5 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG04 | 1294 | 140.81 | 7.89 | fruit.S4 | |

| Aco001135.1 | AcABCB6 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG02 | 1239 | 136.8 | 8.75 | fruit.S4 | |

| Aco018951.1 | AcABCB7 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG12 | 1258 | 140.34 | 8.97 | Stamen.S2 | |

| Aco006827.1 | AcABCB8 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG01 | 1295 | 135.1 | 9.03 | Stamen.S3 | |

| Aco019592.1 | AcABCB9 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG10 | 978 | 138.8 | 8.68 | Flower | |

| Aco013278.1 | AcABCB10 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG24 | 1395 | 139.04 | 8.69 | Ovule.S6 | |

| Aco016496.1 | AcABCB11 | (TMD-NBD)2-NBD | LG11 | 1407 | 174.98 | 6.21 | Root | |

| Aco022325.1 | AcABCB12 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG19 | 1263 | 135.39 | 8.81 | fruit.S1 | |

| Aco003987.1 | AcABCB19 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG15 | 645 | 151.04 | 6.27 | Stamen.S3 | |

| Aco001486.1 | AcABCB20 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG18 | 1270 | 155.88 | 6.4 | Stamen.S1 | |

| Aco008863.1 | AcABCB13 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG09 | 1340 | 132.98 | 8.9 | Stamen.S2 | |

| TAP | Aco007808.1 | AcABCB14 | TMD-NBD | LG21 | 1653 | 70.41 | 7.98 | Stamen.S3 |

| Aco017569.1 | AcABCB15 | TMD-(NBD)2-TMD-NBD | LG09 | 756 | 179.38 | 6.29 | fruit.S4 | |

| Aco015743.1 | AcABCB16 | TMD2-NBD | LG09 | 741 | 82.03 | 9.05 | Ovule.S4 | |

| Aco017326.1 | AcABCB17 | TMD-NBD | LG01 | 755 | 82.29 | 8.86 | Ovule.S2 | |

| ATM | Aco011166.1 | AcABCB18 | TMD-NBD | LG04 | 309 | 82.67 | 9.32 | fruit.S7 |

| Subfamily C, 16 members | ||||||||

| Aco009750.1 | AcABCC1 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG10 | 1545 | 170.6 | 7.71 | Flower | |

| Aco014828.1 | AcABCC2 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG14 | 1543 | 173.73 | 6.83 | Ovule.S1 | |

| Aco027927.1 | AcABCC3 | (TMD-NBD)2 | scaffold_1613 | 1544 | 170.76 | 8.16 | Stamen.S5 | |

| Aco019200.1 | AcABCC4 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG13 | 1404 | 154.1 | 6.18 | Stamen.S4 | |

| Aco010163.1 | AcABCC5 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG25 | 1522 | 168.42 | 8.27 | Flower | |

| Aco019507.1 | AcABCC6 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG07 | 2068 | 228.97 | 7.1 | Ovule.S3 | |

| Aco009944.1 | AcABCC7 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG10 | 1463 | 163.87 | 8.43 | Stamen.S4 | |

| Aco015193.1 | AcABCC8 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG05 | 1463 | 163.62 | 8.82 | fruit.S3 | |

| Aco000353.1 | AcABCC9 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG12 | 1491 | 166.33 | 7.94 | Stamen.S5 | |

| Aco005539.1 | AcABCC10 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG11 | 1485 | 164.82 | 8.42 | Stamen.S1 | |

| Aco006625.1 | AcABCC11 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG01 | 1583 | 177.22 | 8.71 | Ovule.S2 | |

| Aco025745.1 | AcABCC12 | NBD | LG01 | 348 | 39.08 | 5.29 | Ovule.S1 | |

| Aco016941.1 | AcABCC13 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG02 | 1285 | 143.55 | 6.29 | Petal.S3 | |

| Aco017858.1 | AcABCC14 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG23 | 1261 | 140.25 | 6.04 | Sepal.S2 | |

| Aco012910.1 | AcABCC15 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG03 | 1514 | 169.94 | 8.6 | Leaf | |

| Aco016196.1 | AcABCC16 | TMD-NBD | LG17 | 309 | 33.65 | 9.69 | Ovule.S4 | |

| Subfamily D, 2 members | ||||||||

| Aco023353.1 | AcABCD1 | (TMD-NBD)2 | LG18 | 1342 | 149.88 | 9.16 | Stamen.S5 | |

| Aco010685.1 | AcABCD2 | TND-NBD | LG10 | 750 | 83.8 | 8.48 | Stamen.S3 | |

| Subfamily E, 1 members | ||||||||

| Aco010811.1 | AcABCE1 | NBD2 | LG10 | 605 | 68.22 | 8.04 | Stamen.S5 | |

| Subfamily F, 5 members | ||||||||

| Aco010200.1 | AcABCF1 | NBD3 | LG25 | 601 | 67.25 | 6.07 | Petal.S3 | |

| Aco006898.1 | AcABCF2 | NBD3 | LG22 | 603 | 67.03 | 6.37 | Leaf | |

| Aco009295.1 | AcABCF3 | NBD3 | LG22 | 719 | 79.99 | 5.92 | Stamen.S1 | |

| Aco018812.1 | AcABCF4 | NBD2 | LG13 | 742 | 81.44 | 5.87 | Stamen.S4 | |

| Aco000176.1 | AcABCF5 | NBD3 | LG12 | 717 | 79.54 | 6.07 | fruit.S2 | |

| Subfamily G,42 members | ||||||||

| PDR | Aco005449.1 | AcABCG1 | TMD-NBD-TMD2 | LG11 | 1234 | 140.02 | 7.35 | Sepal.S2 |

| Aco005451.1 | AcABCG2 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG11 | 1393 | 157.13 | 8.66 | Stamen.S1 | |

| Aco027149.1 | AcABCG6 | (NBD-TMD)2 | scaffold_1231 | 1419 | 159.96 | 8.93 | Sepal.S3 | |

| Aco009786.1 | AcABCG8 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG10 | 1347 | 151.89 | 8.83 | Flower | |

| Aco006783.1 | AcABCG12 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG01 | 1456 | 164.5 | 8.47 | fruit.S5 | |

| Aco006142.1 | AcABCG13 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG16 | 1476 | 166.35 | 6.59 | Sepal.S1 | |

| Aco023493.1 | AcABCG19 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG01 | 1416 | 160.42 | 7.85 | Stamen.S4 | |

| Aco015369.1 | AcABCG20 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG23 | 1449 | 161.94 | 8.62 | Stamen.S5 | |

| Aco021666.1 | AcABCG21 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG07 | 1282 | 145.07 | 8.65 | fruit.S1 | |

| Aco009791.1 | AcABCG31 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG10 | 1452 | 165.01 | 8.77 | Ovule.S7 | |

| Aco006143.1 | AcABCG36 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG16 | 1410 | 158.85 | 6.51 | Ovule.S4 | |

| Aco014323.1 | AcABCG39 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG05 | 1450 | 164.01 | 7.54 | Sepal.S2 | |

| Aco013658.1 | AcABCG41 | (NBD-TMD)2 | LG13 | 1452 | 164.64 | 7.72 | Stamen.S3 | |

| Aco015172.1 | AcABCG42 | NBD2-TMD-NBD-TMD | LG05 | 1584 | 177.88 | 8.91 | Stamen.S4 | |

| WBC | Aco010405.1 | AcABCG3 | NBD-TMD | LG03 | 727 | 80.78 | 9.09 | Root |

| Aco030876.1 | AcABCG4 | NBD-TMD | scaffold_1304 | 612 | 65.76 | 8.91 | Sepal.S3 | |

| Aco011308.1 | AcABCG5 | NBD-TMD | LG01 | 610 | 66.69 | 9.39 | fruit.S5 | |

| Aco021246.1 | AcABCG7 | NBD-TMD | LG10 | 691 | 75.26 | 8.96 | fruit.S1 | |

| Aco009154.1 | AcABCG9 | NBD-TMD | LG09 | 642 | 70.19 | 8.61 | Stamen.S3 | |

| Aco006105.1 | AcABCG10 | NBD-TMD | LG16 | 591 | 64.95 | 9.14 | Root | |

| Aco010632.1 | AcABCG11 | NBD-TMD | LG07 | 723 | 80.1 | 9.18 | Stamen.S2 | |

| Aco023881.1 | AcABCG14 | NBD | LG20 | 88 | 9.32 | 10.37 | / | |

| Aco007271.1 | AcABCG15 | NBD-TMD | LG23 | 677 | 75.25 | 9.59 | Ovule.S1 | |

| Aco020513.1 | AcABCG16 | NBD | LG01 | 283 | 31.43 | 11.09 | Leaf | |

| Aco010077.1 | AcABCG17 | NBD-TMD | LG25 | 714 | 78.57 | 8.54 | Ovule.S4 | |

| Aco001046.1 | AcABCG18 | Arf-NBD-TMD | LG02 | 896 | 100.18 | 8.27 | fruit.S7 | |

| Aco021024.1 | AcABCG22 | NBD-TMD | LG15 | 743 | 81.87 | 9.15 | Sepal.S1 | |

| Aco002328.1 | AcABCG23 | NBD-TMD | LG04 | 612 | 68.93 | 6.81 | Root | |

| Aco023879.1 | AcABCG24 | NBD | LG20 | 201 | 21.67 | 9.49 | Root | |

| Aco003255.1 | AcABCG25 | NBD-TMD | LG17 | 605 | 65.4 | 9.38 | Ovule.S7 | |

| Aco023619.1 | AcABCG26 | NBD-TMD | LG19 | 641 | 71.96 | 9.36 | Stamen.S4 | |

| Aco013155.1 | AcABCG27 | NBD-TMD | LG24 | 601 | 66.02 | 9.42 | Stamen.S3 | |

| Aco006887.1 | AcABCG28 | NBD | LG22 | 1089 | 120.53 | 9.12 | Ovule.S5 | |

| Aco007658.1 | AcABCG29 | NBD-TMD | LG08 | 721 | 79.81 | 8.84 | Flower | |

| Aco001237.1 | AcABCG30 | NBD-TMD | LG02 | 728 | 80.13 | 7.59 | Flower | |

| Aco031846.1 | AcABCG32 | NBD-TMD | scaffold_3635 | 372 | 39.56 | 8.97 | Stamen.S1 | |

| Aco004405.1 | AcABCG33 | NBD-TMD | LG05 | 605 | 64.96 | 8.82 | Sepal.S4 | |

| Aco000542.1 | AcABCG34 | NBD-TMD | LG12 | 642 | 70.76 | 10.47 | Leaf | |

| Aco010996.1 | AcABCG35 | NBD-TMD | LG04 | 707 | 77.84 | 8.43 | Sepal.S2 | |

| Aco005255.1 | AcABCG37 | NBD-TMD | LG07 | 720 | 79.28 | 8.97 | Petal.S3 | |

| Aco001503.1 | AcABCG38 | NBD-TMD | LG18 | 794 | 87.24 | 9.1 | Stamen.S3 | |

| Aco019952.1 | AcABCG40 | NBD | LG08 | 861 | 96.25 | 9.2 | Stamen.S4 | |

| Subfamily I, 9 members | ||||||||

| Aco008459.1 | AcABCI1 | NBD | LG19 | 224 | 24.87 | 9.69 | Petal.S3 | |

| Aco028846.1 | AcABCI2 | NBD | scaffold_627 | 301 | 32.04 | 8.48 | Stamen.S1 | |

| Aco018474.1 | AcABCI3 | NBD | LG21 | 431 | 48.82 | 7.17 | Stamen.S1 | |

| Aco005118.1 | AcABCI4 | NBD | LG07 | 283 | 30.25 | 8.56 | Sepal.S1 | |

| Aco001741.1 | AcABCI5 | NBD | LG18 | 307 | 33.24 | 8.68 | Stamen.S2 | |

| Aco007380.1 | AcABCI6 | NBD | LG23 | 326 | 34.26 | 6.62 | Stamen.S1 | |

| Aco006975.1 | AcABCI7 | NBD | LG22 | 291 | 32.74 | 5.48 | fruit.S4 | |

| Aco030323.1 | AcABCI8 | NBD | scaffold_1361 | 312 | 32.85 | 6.4 | Petal.S2 | |

| Aco004516.1 | AcABCI9 | NBD | LG05 | 350 | 38.23 | 8.2 | fruit.S3 | |

Columns one to nine show the subgroup names, gene transcript ID, gene name, proteins gross topology (domain, orientation, number of modules, from “-NH3” to “-COOH”), chromosome location, numbers of amino acid residues in the gene translation product, proteins size, protein isoeletric point and main expression location.

Phylogenetic Analysis

To understand the phylogenetic relationship of ABC proteins between pineapple and Arabidopsis, all the identified ABC amino acid sequences of pineapple and Arabidopsis were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. AcABC and AtABC protein sequences were aligned using MAFFT with default parameters5. Then, FastTree software was used to establish phylogenetic tree using 1,000 resamples, and constructed by maximum-likelihood using the JTT + CAT model. FastTree provides local support values by the Shimodaira-Hasegawa (SH) test, the resulting support values were closely correlated with the traditional bootstrap (r = 0.975) (Price et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2017). The local support values below 60 are hidden in the constructed tree. All amino acid sequences were used for phylogenetic and alignments analysis in the study were supplied in Supplementary Datasets S1, S2.

Gene Structure Analysis and Conserved Motif Identification

The exon–intron characteristics of the ABC genes family were exhibited using the Gene Structure Display Server6 (Guo et al., 2007). Through a comparison with the full-length predicted coding sequence (CDS). The motifs of the AcABCG proteins were determined with the appropriate number of motifs using the MEME program7. The lower E-value (the most statistically significant), the more accurate of expected motifs.

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

The wild-type Arabidopsis background Col-0 (CS60000) and the T-DNA insertions of AtABCG1 (abcg1-1: SALK_061511; abcg1-2: SALK_055389) and AtABCG16 (abcg16-1: SALK_087501; abcg16-2: SALK_119868C) were obtained from Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC)8. Pineapple (Ananas comosus) variety MD2 was collected by Qin Lab9. Pineapple were grown in plastic pots with soil mix [peat moss: perlite = 2:1 (v/v)] and placed in greenhouse at about 30°C with light availability of 60–70 mMolL-1 photons m-2s-1 under 70% humidity with 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod. Arabidopsis was grown with the conditions as described by Cai et al. (2017).

RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR

Tissue samples of MD2 were collected from different developmental stages of ovule, petal, sepal and stamen. The criterion of different stage samples was referenced to Su et al. (2017), including seven stages of ovule (Ov1-Ov7), three stages of petal (Pe1–Pe3), five stages of stamen (St1–St5) and four stages of sepal (Se1–Se4). Collected samples were quickly stored in liquid nitrogen until total RNA extraction. The RNA was extracted following manufacturer’s protocol using RNA extraction Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Shanghai, China). Total RNA was diluted with nuclease-free water and then mRNA was isolated, following by fragmentation, and the first and second strand cDNA synthesized. Double-stranded cDNA was then purified using 1.8× Agencourt AMPure XP Beads. Performing End Repair/dA-tail of cDNA Library followed by adaptor ligation using Blunt/TA Ligase Master Mix and diluted NEB Next Adaptor. Purifying the ligation reaction and approximate insert size was kept 25–400 bp with final library was set to 300–500 bp. Performing PCR Library construction followed by purity of the PCR reaction using Agencourt AMPure XP Beads and assessed library quality on a Bioanalyzer® (Agilent high sensitivity chip) and send to company for sequencing (NEB next Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina Biolabs). The RNA-seq data of root, leaf, flower and developing fruit were download from NCBI database10, and all of RNA-seq data were analyzed following Trapnell et al. (2012). Raw reads were filtered by TRIMMOMATIC v0.3 to remove the adapter sequence, the clean reads were then aligned using the Tophat software with default parameters. Alignment results were processed using Cufflinks, and FPKM values were calculated by using Cuffdiff (FC ≥ 2, FDR ≤ 0.05) for following Dai et al. (2017) analysis. R software was employed to construct the heat-map using FPKM values of RNA-seq for each gene. RNA-seq data were further validated by qRT-PCR analysis in different tissues (i.e., ovule Ov3, stamen St2, sepal Se3 and petal Pe3). qRT-PCR was carried out using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, China) on a Bio-Rad Real-time PCR system (Foster, United States), and the program was: 95°C for 30 s; 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s; 95°C for 15 s. Three technical replicates and at least three independent biological replicates were performed in each condition.

Vector Construction

The full-length of coding sequence of AcABCG38 were amplified using primers listed in Supplementary Table S4. The PCR fragment was cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced. The positive clone was recombined into the destination vector pGWB505 by LR reaction. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens (GV3101) with AcABCG38 was used to transform into the abcg1-2abcg16-2 double mutant and WT using a floral dip procedure (Clough and Bent, 1998). The multiple independent T1 plants were analyzed.

Alexander Red Staining

Arabidopsis were fixed in FAA for 24 h, and then picked the anthers on slide, heated until the pollens were dyed in red color. The stained anthers were taken picture by microscope (Carl-Zeiss, Germany).

Results

Identification and Characterization of the Pineapple ABC Transporters

To identify the ABC gene family in pineapple, the HMMER3.0 (Eddy, 2011) was used to get ABC protein sequences containing PFAM ABC domain (PF00005) in pineapple genome database downloaded from the Phytozome v12.1. To obtain accurate AcABC members, the conserved sequences of AcABC were analyzed using NCBI and sequences that lacked ABC annotation were removed. Finally, a total of 100 ABC genes were identified in the pineapple genome by BLAST and phylogenetic analysis with Arabidopsis ABC proteins. Those genes chromosomes distribution was showed in Supplementary Figure S1. The 100 pineapple proteins were grouped into eight subfamilies, including 5 ABCAs, 20 ABCBs 16 ABCCs, 2 ABCDs, 1 ABCEs, 5 ABCFs, 42 ABCGs and 9 ABCIs (Table 1). Although the ABCH subfamily were ubiquitously existed in insects, fishes, echinodermata and myxomycetes (Shao et al., 2013), and it was not identified in the pineapple genomes, this result is similar to the finding of other plant species (Pang et al., 2013). The pineapple ABC genes were named and further classified according to the sequence similarity of Arabidopsis ABC genes. AcABCAs were subdivided into two types: ATH (ABC1 homologous) and AOH (ABC1 homologous), and AcABCBs included three subgroups: MDR (multidrug resistance protein), TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing) and ATM (ABC transporter of the mitochondria); AcABCGs were also classified into two categories: WBC (white-brown complex homologue) and PDR (pleiotropic drug resistance) (Sánchezfernández et al., 2001). The amino acids numbers ranged from 88 aa (AcABCG14) to 2068 aa (AcABCC6) with the corresponding molecular weight varied from 9.32 to 228.97 Kd. The series of information about AcABCs including subgroup names, gene transcript ID, numbers of amino acid residues, proteins size, protein isoelectric point and main expression location were showed in Table 1.

Phylogenetic Analysis of ABC Family in Pineapple

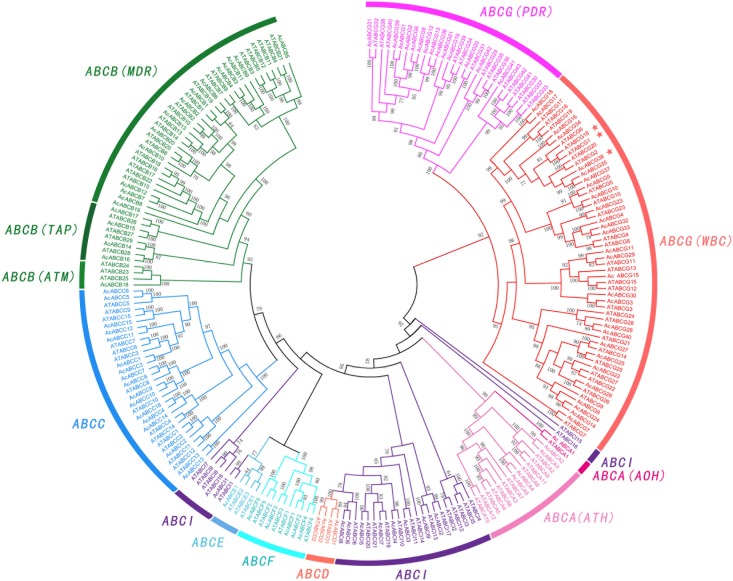

To further understand the relationship between the AcABCs and AtABCs, full-length protein sequences of pineapple and Arabidopsis ABCs were aligned using MAFFT, and a combined phylogenetic tree was constructed using FastTree. The result showed that the ABC genes of these two species can be divided into eight subfamilies (Figure 1). Among those subfamilies, ABCG had the largest members with 42 pineapple genes and 43 Arabidopsis genes. ABCB was the second largest subgroup, containing eighteen pineapple genes and twenty-eight Arabidopsis genes. The smallest subgroup was ABCD and ABCE, both contain only four members: two AcABCD genes and two AtABCD genes, and one AcABCEs and three AtABCEs. According to functional characteristic, the ABCA proteins were further classified into in two distinct types with two members in ATH and 22 in AOH. Similarly, the ABCBs subfamily were also divided into three groups (34 MDRs, 8 TAPs and 4 ATMs) and ABCGs were divided into two types (56 WBCs and 29 PDRs). While ABCI subfamily was divided into three clusters in phylogenetic tree (Figure 1). One of which contained only two Arabidopsis members (AtABCI15 and AtABCI16) without any pineapple members, indicating that the ABCI family could had undergone evolutionary divergence between dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous plants.

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic relationship of ABC gene among Pineapple (Ac) and Arabidopsis (At). All the AcABC protein sequences were aligned by using MAFFT and phylogenetic tree was constructed using FastTree. Different colors represented individual subfamily. Every subfamily had another classified names: ATH (ABC1 homologous), AOH (ABC1 homologous), MDR (multidrug resistance protein), TAP (transporter associated with antigen processing), ATM (ABC transporter of the mitochondria), WBC (white-brown complex homolog), PDR (pleiotropic drug resistance). AcABCG38, AtABCG1 and AtABCG16 were indicated by asterisk.

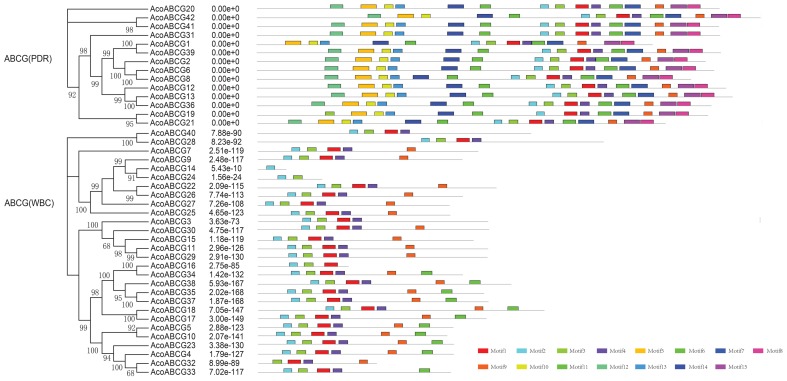

Gene Structure Analysis and Conserved Motif Identification

To investigate the structure diversity, we analyzed the predicted CDS of individual pineapple ABC gene family using Gene Structure Display Server (Guo et al., 2007). The result showed that the exons number of AcABC genes varied from 1 to 41. AcABCB15 had the maximum exons numbers, while seven AcABC genes (AcABCG4, AcABCG10, AcABCG14, AcABCG23, AcABCG32, AcABCG33 and AcABCG38) have only one exon with no UTR (Figure 2). To reveal the diversification of ABCG subfamily in pineapple, the putative motifs were predicted and identified by MEME with the motif numbers setting from 1 to 15 (Bailey and Elkan, 1994). The ABCG subfamily had two types: PDR and WBC. The numbers of motifs in each AcPDRs were approximately twice as many as that of AcWBCs (Figure 3). AcABCG14 belonging to AcWBCs had only one motif; while most of AcPDRs contained 15 motifs except for AcABCG1, AcABCG19, and AcABCG42.

FIGURE 2.

Intron–exon structure of AcABC genes in pineapple genome. Yellow bars indicates exon (CDS), Blue bars indicated UTR while plain lines showing introns. black lines represented introns. On the left panel is the phylogenetic trees of ABC transporter proteins in pineapple which was constructed by Maximum likelihood method. The numbers on the right indicate the genomic length of the corresponding genes. bp, base pair.

FIGURE 3.

The motif analysis of AcABCG proteins in pineapple. Motifs with specific colors can be find on respective AcABCG genes. The combined phylogenetic trees of AcABCG subfamily on the left panel. The motifs of corresponding proteins are shown on the right panel with specific colors on behalf of different motifs using the MEME motif search tool (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme). The order of the motifs corresponds to their position within individual protein sequences.

Expression Profiles of Pineapple ABC Genes in Different Tissues

To analyze the expression profiles, the expression level of 100 AcABC genes were analyzed based on their FPKM values from RNA-seq data of different tissues. On basis of the average log values of each gene in given tissue, a hierarchical cluster and expression patterns of these genes were generated (Figure 4). According to the expression specificity, those AcABC genes could be classified into five types. In type I, the genes expressed ubiquitously in most or all tissues such as AcABCB1, AcABCC2, AcABCE1, AcABCF1 and AcABCG31. Conversely, in type II, eleven genes demonstrated comparatively low expression levels in almost all tissues, especially, AcABCB3, AcABCG14 and AcABCG24 had extremely low expression. Sixty-three genes were moderately and evenly expressed in all organs in type III. The eleven genes in type IV had remarkably high expression levels in particular vegetative and reproductive organs (i.e., AcABCA5 and AcABCC4 in ovule and stamen, AcABCC7, AcABCC9, and AcABCG29 in ovule). The ten genes were highly and specifically expressed in one or two development stages of organs in type V (AcABCA4 in root, AcABCB5, AcABCB17 and AcABCAI2 in petal Pe3, AcABCC14 and AcABCG13 in flower and leaf, AcABCG20 in stamen St1, St2, and St5, AcABCG42 in stamen St1–St4 as well as AcABCG26 and AcABCG38 in stamen St3 and St4) (Figure 4). We found some genes, which belong to the same group, had analogical expression profiles. For example, the majority of the AcABCC genes were relatively highly expressed in all of tissues, and nearly all of the AcABCI members had similar expression levels. To further verify the reliability from RNA-seq data, the expression levels of four genes (AcABCA5, AcABCG38, AcABCD2 and AcABCI2) in four different tissues were selected for qRT-PCR validation. The results revealed that expression patterns of qRT-PCR were consistent with that from RNA-seq analysis (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Tissue-specific expression profiles of AcABC genes in pineapple. Heat-map of tissue-specific expression profiles of AcABC genes in pineapple. RNA-seq expression level can be understood using the given scale and roman numbers on right-side shows hierarchical clusters based on gene expression. The combined phylogenetic trees of pineapple ABC family on the left panel. Red color indicates high levels of transcript abundance, and green indicates low transcript abundance. The color scale is shown at the bottom. Samples are mentioned at the top of each lane: ovule S1–S7, sepal S1–S4, stamen S1–S5, petal S1–S3, root, leaf, flower, fruit S1–S7. “S” is abbreviation of word “stage.”

FIGURE 5.

Validation of AcABC genes RNA-seq by qRT-PCR analysis of four genes’ expression at five different tissues. Line graphs are constructed from relative gene expression (Left side Y-Axis) in different tissues (qRT-PCR) data and FPKM values (RNA-seq) data (Right side Y-Axis) for these tissues.

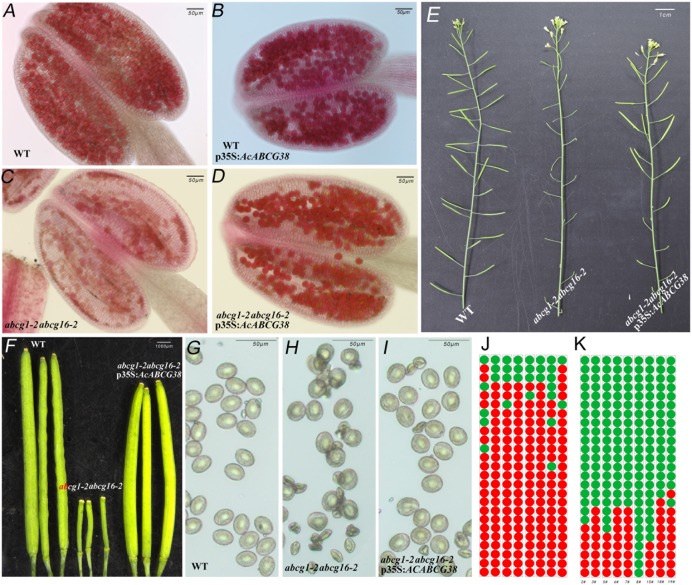

AcABCG38 Might Play Crucial Roles in Pollen and Anther Development

As showed in Figure 4, the expression profiling revealed that AcABC38 expressed highly in stamen St3 and St4, implying that this gene may be involved in stamen development. As previous reports, two ABC genes (AtABCG1 and AtABCG16) play significant roles in pollen development (Yadav and Reed, 2014; Yim et al., 2016). Base on phylogenetic analysis, our results showed that AtABCG1, AtABCG16 and AcABCG38 clustered the same subclade. Those results further indicated AcABCG38 functions in pollen development. Thereby, we cloned AcABCG38 gene and transformed into the Arabidopsis double mutant abcg1-2abcg16-2 to check it whether functions or not.

As showed in Figure 6, the abcg1-2abcg16-2 double mutant has short siliques, lower seed set (Figures 6E,F,J) and collapsed pollens (Figures 6C,H). Reciprocal crosses between abcg1-2abcg16-2 double mutant and wild type showed that the reduced fertility in abcg1-2abcg16-2 was due to defective male gametophyte function (Supplementary Table S1). Moreover, the transmission of abcg1 allele through pollen but not female reproductive organ was significantly reduced in abcg16-2/abcg16-2 background (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Table S2). While the transmission of abcg16 alleles through both male and female was not affected in abcg1-2/abcg1-2 background (Supplementary Table S3). These results suggested that AtABCG1 plays dominant role in controlling male gametophytic function.

FIGURE 6.

Over-expressing of AcABCG38 can partly recover the fertility and pollen development defects of double mutant abcg1-2abcg16-2. (A) Alexander red staining of WT anther. (B) Alexander red staining of p35S:AcABCG38 anther. (C) Alexander red staining of double mutant of abcg1-2abcg16-2 anther. (D) Alexander red staining of the abcg1-2abcg16-2 p35S:AcABCG38 line 8# anther. (E) Main branch of the plants with genotype as indicated (left: col-0, mid: abcg1-2abcg16-2, right: abcg1-2abcg16-2 p35S:AcABCG3 line 2#). (F) Siliques of plants with genotype as indicated (left: col-0, mid: abcg1-2abcg16-2, right: transgenic plant 8# in abcg1-2abcg6-2 background). (G) Mature pollens of col-0. (H) Mature pollens of abcg1-2abcg16-2 plant. (I) Mature pollens of the abcg1-2abcg16-2 p35S:AcABCG38 8#. (J) Seed set phenotype of the 25 siliques from bottom to top in main branch of the abcg1-2abcg16-2 plants. Red dots represent the short siliques with reduced seed set; green dots represent the normal siliques with full seed set. (K) Seed set phenotype of the 25 siliques from bottom to top in main branch of the individual abcg1-2abcg16-2 p35S:AcABCG38 lines.

In the T1 generation of the p35S:AcABCG38 transgenic plants, we selected nine individual lines that showed elongated siliques (Figures 6E,F,K) and less aborted pollens (Figures 6D,I) compared with the double mutant abcg1-2abcg16-2 (Figures 6C,E,F,H,J and Table 2), however, they had slightly shorter siliques and higher percentage of aborted pollen compared to WT plants (Figures 6A,E–G and Table 2). These results suggesting that overexpression of AcABCG38 can partially rescue the reduced fertility and pollen abortion phenotype in abcg1-2abcg16-2. The transcript level of AcABCG38 was also evaluated in individual transgenic lines using qRT-PCR to confirm the complemented phenotype with the increased AcABCG38 expression. The results showed that complemented line 8# exhibited the highest transcriptional level of AcABCG38 (Figure 6K, Table 2, and Supplementary Figure S2). Five independent AcABCG38-overexpressing transgenic plants in WT background showed comparable vegetative growth to WT plant and full seed set with normal pollens development as indicated by Alexander red staining (Supplementary Figure S3). Taken together, these results indicated that AcABCG38 plays vital roles in pineapple pollen development.

Table 2.

The abcg1-2abcg6-2 p35S:AcABCG38 plants have higher percentage of normal pollen than p35S:AcABCG38 plants.

| WT | abcg1-2-/- abcg16-2-/- | 2# | 3# | 5# | 6# | 7# | 8# | 15# | 18# | 19# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 1331 | 275 | 965 | 656 | 591 | 979 | 478 | 1044 | 1418 | 657 | 784 |

| Abnormal | 3 | 1015 | 434 | 449 | 476 | 551 | 353 | 275 | 633 | 448 | 393 |

| Total | 1334 | 1290 | 1399 | 1105 | 1066 | 1530 | 831 | 1319 | 2051 | 1105 | 1177 |

| Normal (%) | 99.48 | 21.3 | 69.0 | 59.4 | 55.4 | 64.0 | 57.3 | 79.2 | 69.1 | 59.5 | 66.6 |

The nine abcg1-2abcg6-2 p35S:AcABCG38 transgenic lines (2#, 3#, 5#, 6#, 7#, 8#, 15#, 18#, 19#) in T1 generation were used for pollen phenotype observation. The numbers of pollen grains were counted in culture medium by microscope.

Discussion

Diversity of ABC Transporters in Plants

It is reported that the ABC proteins are relatively conserved across different species but distinct between plants and animals (Xie et al., 2012; Pang et al., 2013). Compared with animal ABC transporters, plant ABC proteins exist numerous and diverse. A number of ABC genes are found in different plant species, e.g., the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana contains 129 ABC genes, maize 130 ABC transporters and rice 128 transporters (Ponte-Sucre, 2007; Pang et al., 2013). In this study, 100 AcABC proteins have been identified genome-wide. Additionally, those ABC proteins can be divided into as many as eight subfamilies, each subfamily can further be divided into a quantity of subsets (Shao et al., 2013). We also identified 18 AcABCB genes, 16 AcABCC genes and 42 AcABCG genes in pineapple genome, accounting for 76% of all AcABC members. Among those subfamilies, AcABCB genes includes 13 AcMDRs, 4 AcTAPs and 1 AcATMs in this study. Previous studies reported that MDRs are responsible for transporting varieties of substrates, such as lipid proteins, bactericin, peptides, cell surface components, auxin transport and so on (Noh et al., 2001; Sasaki et al., 2002; Moons, 2008). ATMs play a vital role in resistance to heavy metals toxicity in plants (Kim et al., 2006). In Arabidopsis, two proteins AtMRP4 and AtMRP5 particularly expressed in guard cells and control stomata conductance (Gaedeke et al., 2001; Frelet, 2003). Maize MRP (ZmABCC5), involved in resistance system, also plays role in anthocyanin transport (Goodman et al., 2004). As showed in Figure 4, the majority of AcABCC proteins were expressed in all organs in our study, suggesting their potential role in pineapple growth and development. ABCG subfamily participates in transporting lipid precursors of cutin and wax (Pighin et al., 2004). AcABCG contains 42 members and their expression profiles suggests that either they are highly expressed or specific to tissue. Those data clearly indicate that plants require numerous ABC proteins for growth and development. The reason maybe that plants develop a complicated transporter system to survival in diversity environment through a rapid divergence across a long process of natural evolution and selection.

AcABC Gene Expression Profiles Analysis

Recently, the release of pineapple genome sequence makes it available for researchers to explore pineapple specific agronomic traits (Ming et al., 2015). To explore the function of ABC transporters in pineapple, we downloaded the pineapple different tissues RNA-seq data, and analyzed the expression levels of 100 AcABC genes based on their FPKM values. As showed in Figure 4, a hierarchical cluster and expression patterns of these genes were generated. Those AcABC genes could express specifically. For example, AcABCB6 expressed in floral organs, AcABCB5 and AcABCB17 in Pe3 shows tissue-specific expression. AtABCB1 localized in the plasma membrane and participated in IAA-induced plant development (Sasaki et al., 2002). AcABCB1, clustered with AtABCB1 in same clades by phylogenetic analysis, expressed broadly in all pineapple tissues, suggesting that AcABCB1 could also be involved in auxin induced pineapple development.

Interesting, some AcABCs expressed remarkably in reproductive tissues, e.g., AcABCA5 and AcABCC4 in ovule and stamen; AcABCC7, AcABCC9 and AcABCG29 in ovule; and AcABCG31 was specific to floral organs; indicating their potential roles in pineapple flower development. AtABCG1 and AtABCG16 and redundantly in controlling Arabidopsis pollen development (Yadav and Reed, 2014; Yim et al., 2016) and suggests that AcABCG38 may also be involved in pollen development. The expression pattern of AcABCs together with the reported functions of corresponsive Arabidopsis orthologs could provide clue to understand the function of AcABCs in pineapple.

AcABC38 Regulates Pineapple Reproductive Development

Sexual propagation could be an effective and potential way to improve the pineapple agricultural production (Kondrashov, 1993). However, the function of genes in pineapple development are barely reported. Our study aims to identify ABC genes that are crucial for pineapple propagation. For instance, AcABCG26 and AcABCG38 were highly expressed in different stages of stamen (Figure 4). The expression profiles of these genes in reproductive organs at different developmental stages could determine its functional role. To validate functions of AcABCs, AcABCG38 was selected for functional study as it showed high expression in stamens at St3 and St4. Also Arabidopsis homologs of AcABCG38, AtABCG1 and AtABCG16 are known to work redundantly in pollen development (Yadav and Reed, 2014; Yim et al., 2016).

Over-expression of AcABCG38 in Arabidopsis double mutant abcg1-2abcg16-2 was able to partly rescue the defective pollen development phenotype, indicating that AcABCG38 might play important roles for pollen development in pineapple. The mechanism underlying the regulation of AcABCG38 on pineapple pollen development is still unknown and further studies could shed light on it. Present study of pineapple AcABC genes provide useful information on gene function and may act as foundation for future pineapple research.

Conclusion

The ABC transporter gene families are ubiquitous and important in all kind of life events for all life organism. Whereas the information about pineapple ABC gene family is not available. Here we identified 100 ABC genes in the pineapple genome and grouped them into eight subfamilies. Gene expression profiling revealed many tissue specific genes particularly in reproductive organs. Furthermore, over-expression of AcABCG38 in Arabidopsis double mutant abcg1-2abcg16-2 partly rescued the defective pollen development phenotype, indicating that AcABCG38 might have important function for pollen development in pineapple. Overall, the characterization and expression profile study of pineapple AcABC genes provide useful information for gene functional study as well as insights into future pineapple researches for improving pineapple sexual plant reproduction.

Author Contributions

Created and designed the experiments: PC, YiL, and YQ. Carried out the experiments: PC, LZ, and ZH. The analysis of data: YiL. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: PC, LZ, ZH, MY, BH, YaL, SA, ZZ, ZR, and LL. Wrote the paper: PC and YQ.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1605212; 31522009; 31470284 to YQ; 31600249 to LZ), Fujian Innovative Center for Germplasm Resources and Innovation Project of Characteristic Horticultural Crop Seed Industry (KLA15001D), FAFU International collaboration Project supported by Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2017J01601).

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2017.02150/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Distribution of ABC genes in pineapple genome. MapChart was used to located genes on chromosomes. Respective chromosome numbers are indicated at the top of each bar. The bar on the left is respective ABC genes. Every bar has different colors, and the length of bar represents the size chromosome in pineapple.

FIGURE S2 | Relative expression of AcABCG38 different transgenic lines in abcg1-2abcg6-2 background (there are nine transgenic lines for first generation, respectively, lines: 2#, 3#, 5#, 6#, 7#, 8#, 15#, 18#, 19#) and abcg1-2abcg16-2 (negative control). The result shows that there are consistent with rescued phenotype (i.e., line 8# have detected the highest expression, and it was the most perfectly recovered phenotype line (Figures 6D,E,K).

FIGURE S3 | Alexander red staining. Five transgenic lines in col-0 (A) and abcg1-2abcg16-2 background (B) respectively.

TABLE S1 | Reduced seed-set phenotypes in double mutants abcg1-2/abcg1-2 abcg16-2/abcg16-2 result from defective male reproductive function.

TABLE S2 | Transmission of abcg1 alleles proves through male gametes is significantly deviated from expect in abcg16-2/abcg16-2 background.

TABLE S3 | Transmission of abcg16 allele proves that AtABCG16 is not affected in abcg1-2/abcg1-2 background.

TABLE S4 | The primers of vectors construction and qRT-PCR.

DATASET S1 | All the AcABC and ATABC protein sequences.

DATASET S2 | The used alignments of all the AcABC and ATABC protein sequences.

References

- Aizen M. A., Harder L. D. (2007). Expanding the limits of the pollen-limitation concept: effects of pollen quantity and quality. Ecology 88 271–281. 10.1890/06-1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumuganathan K., Earle E. D. (1991). Nuclear DNA content of some important plant species. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 9 208–218. 10.1007/BF02672069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L., Elkan C. (1994). Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 2 28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H., Zhao L., Wang L., Zhang M., Su Z., Cheng Y., et al. (2017). ERECTA signaling controls Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture through chromatin-mediated activation of PRE1 expression. New Phytol. 214 1579–1596. 10.1111/nph.14521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campa D., Pardini B., Naccarati A., Vodickova L., Novotny J., Forsti A., et al. (2008). A gene-wide investigation on polymorphisms in the ABCG2/BRCP transporter and susceptibility to colorectal cancer. Mutat. Res. 645 56–60. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Zhang X., Liu X., Zhang L. (2017). Evolutionary analysis of MIKCc-type MADS-box genes in gymnosperms and angiosperms. Front. Plant Sci. 8:895. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998). Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X., Bai Y., Zhao L., Dou X., Liu Y., Wang L., et al. (2017). H2A.Z represses gene expression by modulating promoter nucleosome structure and enhancer histone modifications in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 10 1274–1292. 10.1016/j.molp.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson A. L., Dassa E., Orelle C., Chen J. (2008). Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72 317–364. 10.1128/MMBR.00031-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy S. R. (2011). Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLOS Comput. Biol. 7:e1002195. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassinou Hotegni V. N., Lommen W. J., Agbossou E. K., Struik P. C. (2015). Influence of weight and type of planting material on fruit quality and its heterogeneity in pineapple [Ananas comosus (L.) Merrill]. Front. Plant Sci. 5:798. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelet A. (2003). The plant multidrug resistance ABC transporter AtMRP5 is involved in guard cell hormonal signalling and water use. Plant J. 33 119–129. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.016012.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaedeke N., Klein M., Kolukisaoglu U., Forestier C., Müller A., Ansorge M., et al. (2001). The Arabidopsis thaliana ABC transporter AtMRP5 controls root development and stomata movement. EMBO J. 20 1875–1887. 10.1093/emboj/20.8.1875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler M., Kolukisaoglu H. U., Bouchard R., Billion K., Berger J., Saal B., et al. (2003). TWISTED DWARF1 a unique plasma membrane-anchored immunophilin-like protein, interacts with Arabidopsis multidrug resistance-like transporters AtPGP1 and AtPGP19. Mol. Biol. Cell 14 4238–4249. 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman C. D., Casati P., Walbot V. (2004). A multidrug resistance-associated protein involved in anthocyanin transport in Zea mays. Plant Cell 16 1812–1826. 10.1105/tpc.022574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo A. Y., Zhu Q. H., Chen X., Luo J. C. (2007). GSDS: a gene structure display server. Hereditas 29 1023–1026. 10.1360/yc-007-1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson D. P., Payne S. M. (1994). Vibrio cholerae iron transport systems: roles of heme and siderophore iron transport in virulence and identification of a gene associated with multiple iron transport systems. Infect. Immun. 62 5120–5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins C. F., Linton K. J. (2004). The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11 918–926. 10.1038/nsmb836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Y., Bovet L., Kushnir S., Noh E. W., Martinoia E., Lee Y. (2006). AtATM3 is involved in heavy metal resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 140 922–932. 10.1104/pp.105.074146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein I., Sarkadi B., Váradi A. (1999). An inventory of the human ABC proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1461 237–262. 10.1016/S0005-2736(99)00161-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov A. S. (1993). Classification of hypotheses on the advantage of amphimixis. J. Hered. 84 372–387. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a111358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitis D. A., Zimmerman K., Pringle A. (2017). Is meiosis a fundamental cause of inviability among sexual and asexual plants and animals? Proc. Biol. Sci. 284:20170939. 10.1098/rspb.2017.0939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming R., Vanburen R., Wai C. M., Tang H., Schatz M. C., Bowers J. E., et al. (2015). The pineapple genome and the evolution of CAM photosynthesis. Nat. Genet. 47 1435–1442. 10.1038/ng.3435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moons A. (2008). Transcriptional profiling of the PDR gene family in rice roots in response to plant growth regulators, redox perturbations and weak organic acid stresses. Planta 229 53–71. 10.1007/s00425-008-0810-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman M., Schwander T. (2011). Using parthenogenetic lineages to identify advantages of sex. Evol. Biol. 38 115–123. 10.1007/s11692-011-9113-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noh B., Murphy A. S., Spalding E. P. (2001). Multidrug resistance-like genes of Arabidopsis required for auxin transport and auxin-mediated development. Plant Cell 13 2441–2451. 10.1105/tpc.13.11.2441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto S. P. (2009). The evolutionary enigma of sex. Am. Nat. 174(Suppl. 1), S1–S14. 10.1086/599084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang K., Li Y., Liu M., Meng Z., Yu Y. (2013). Inventory and general analysis of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) gene superfamily in maize (Zea mays L.). Gene 526 411–428. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paponov I. A., Teale W. D., Trebar M., Blilou I., Palme K. (2005). The PIN auxin efflux facilitators: evolutionary and functional perspectives. Trends Plant Sci. 10 170–177. 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckham G. D., Kaneshiro W. S., Luu V., Berestecky J. M., Alvarez A. M. (2010). Specificity of monoclonal antibodies to strains of Dickeya sp. That cause bacterial heart rot of pineapple. Hybridoma 29 383–389. 10.1089/hyb.2010.0034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pighin J. A., Zheng H., Balakshin L. J., Goodman I. P., Western T. L., Jetter R., et al. (2004). Plant cuticular lipid export requires an ABC transporter. Science 306 702–704. 10.1126/science.1102331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponte-Sucre A. (2007). Availability and applications of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter blockers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76 279–286. 10.1007/s00253-007-1017-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. N., Dehal P. S., Arkin A. P. (2010). FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLOS ONE 5:e9490. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol C. J., Kado C. I. (2000). Genetic and biochemical characterization of the pathway in Pantoea citrea leading to pink disease of pineapple. J. Bacteriol. 182 2230–2237. 10.1128/JB.182.8.2230-2237.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard M., Drouin R., Beaulieu A. D. (1998). ABC50 a novel human ATP-binding cassette protein found in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-stimulated synoviocytes. Genomics 53 137–145. 10.1006/geno.1998.5480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger J. G., Ellis A. G. (2016). Distinct effects of pollinator dependence and self-incompatibility on pollen limitation in South African biodiversity hotspots. Biol. Lett. 12:20160253. 10.1098/rsbl.2016.0253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchezfernández R. O., Davies T. G. E., Coleman J. O. D., Rea P. A. (2001). The Arabidopsis thaliana ABC protein superfamily, a complete inventory. J. Biol. Chem. 276 30231–30244. 10.1074/jbc.M103104200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos C., Ventura J. A., Lima N. (2016). New insights for diagnosis of pineapple fusariosis by MALDI-TOF MS technique. Curr. Microbiol. 73 206–213. 10.1007/s00284-016-1041-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T., Ezaki B., Matsumoto H. (2002). A gene encoding multidrug resistance (MDR)-like protein is induced by aluminum and inhibitors of calcium flux in wheat. Plant Cell Physiol. 43 177–185. 10.1093/pcp/pcf025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider E., Hunke S. (1998). ATP-binding-cassette (ABC) transport systems: functional and structural aspects of the ATP-hydrolyzing subunits/domains. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22 1–20. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00358.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao R., Shen Y., Zhou W., Fang J., Zheng B. (2013). Recent advances for plant ATP-binding cassette transporters. J. Zhejiang A F Univ. 30 761–768. [Google Scholar]

- Su Z., Wang L., Li W., Zhao L., Huang X., Azam S. M., et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification of auxin response factor (ARF) genes family and its tissue-specific prominent expression in pineapple (Ananas comosus). Trop. Plant Biol. 10 86–96. 10.1007/s12042-017-9187-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C., Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., Kelley D. R., et al. (2012). Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7 562–578. 10.1038/nprot.2012.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyzack J. K., Wang X., Belsham G. J., Proud C. G. (2000). ABC50 interacts with eukaryotic initiation factor 2 and associates with the ribosome in an ATP-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 275 34131–34139. 10.1074/jbc.M002868200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verrier P. J., Bird D., Burla B., Dassa E., Forestier C., Geisler M., et al. (2008). Plant ABC proteins–a unified nomenclature and updated inventory. Trends Plant Sci. 13 151–159. 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Zhang L., Guo N., Zhang X., Zhang C., Sun G., et al. (2014). Functional properties of a cysteine proteinase from pineapple fruit with improved resistance to fungal pathogens in Arabidopsis thaliana. Molecules 19 2374–2389. 10.3390/molecules19022374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X., Cheng T., Wang G., Duan J., Niu W., Xia Q. (2012). Genome-wide analysis of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter gene family in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39 7281–7291. 10.1007/s11033-012-1558-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav V., Reed J. W. (2014). ABCG transporters are required for suberin and pollen wall extracellular barriers in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26 3569–3588. 10.1105/tpc.114.129049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim S., Khare D., Kang J., Hwang J. U., Liang W., Martinoia E., et al. (2016). Postmeiotic development of pollen surface layers requires two Arabidopsis ABCG-type transporters. Plant Cell Rep. 35 1863–1873. 10.1007/s00299-016-2001-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Wang D., Yang C., Kong N., Shi Z., Zhao P., et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification of the potato WRKY transcription factor family. PLOS ONE 12:e0181573. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z., Fang L. L., Johnsen R., Baillie D. L. (2004). ATP-binding cassette protein E is involved in gene transcription and translation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 323 104–111. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 | Distribution of ABC genes in pineapple genome. MapChart was used to located genes on chromosomes. Respective chromosome numbers are indicated at the top of each bar. The bar on the left is respective ABC genes. Every bar has different colors, and the length of bar represents the size chromosome in pineapple.

FIGURE S2 | Relative expression of AcABCG38 different transgenic lines in abcg1-2abcg6-2 background (there are nine transgenic lines for first generation, respectively, lines: 2#, 3#, 5#, 6#, 7#, 8#, 15#, 18#, 19#) and abcg1-2abcg16-2 (negative control). The result shows that there are consistent with rescued phenotype (i.e., line 8# have detected the highest expression, and it was the most perfectly recovered phenotype line (Figures 6D,E,K).

FIGURE S3 | Alexander red staining. Five transgenic lines in col-0 (A) and abcg1-2abcg16-2 background (B) respectively.

TABLE S1 | Reduced seed-set phenotypes in double mutants abcg1-2/abcg1-2 abcg16-2/abcg16-2 result from defective male reproductive function.

TABLE S2 | Transmission of abcg1 alleles proves through male gametes is significantly deviated from expect in abcg16-2/abcg16-2 background.

TABLE S3 | Transmission of abcg16 allele proves that AtABCG16 is not affected in abcg1-2/abcg1-2 background.

TABLE S4 | The primers of vectors construction and qRT-PCR.

DATASET S1 | All the AcABC and ATABC protein sequences.

DATASET S2 | The used alignments of all the AcABC and ATABC protein sequences.