Abstract

Cronobacter species are important food-borne opportunistic pathogens which have been implicated in the cause of necrotizing enterocolitis, sepsis, and meningitis in neonates and infants. However, these bacteria are routinely found in foodstuffs, clinical specimens, and environmental samples. This study investigated the genetic diversity, antimicrobial susceptibility, and biofilm formation of Cronobacter isolates (n = 40) recovered from spices and cereals in China during 2014–2015. Based on the fusA sequencing analysis, we found that the majority (23/40, 57.5%) of Cronobacter isolates in spices and cereals were C. sakazakii, while the remaining strains were C. dublinensis (6/40, 15.0%), C. malonaticus (5/40, 12.5%), C. turicensis (4/40, 10.0%), and C. universalis (2/40, 5.0%). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis produced 30 sequence types (STs) among the 40 Cronobacter isolates, with 5 STs (ST4, ST13, ST50, ST129, and ST158) related to neonatal meningitis. The pattern of the overall ST distribution was diverse; in particular, it was revealed that ST148 was the predominant ST, presenting 12.5% within the whole population. MLST assigned 12 isolates to 7 different clonal complexes (CCs), 4, 13, 16, 17, 72, 129, and 143, respectively. The results of O-antigen serotyping indicated that C. sakazakii serotype O1 and O2 were the most two prevalent serotypes. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing showed that the 40 Cronobacter isolates were susceptible to most of the antibiotics tested except for ceftriaxone, meropenem, and aztreona. Of the 40 Cronobacter strains tested, 13 (32.5%) were assessed as weak bioflim producers, one (2.5%) was a moderate biofilm producer, one (2.5%) was strong biofilm producer, and the others (62.5%) were non-biofilm producers. MLST and O-antigen serotyping have indicated that Cronobacter strains recovered from spices and cereals were genetically diverse. Isolates of clinical origin, particularly the C. sakazakii ST4 neonatal meningitic pathovar, have been identified from spices and cereals. Moreover, antimicrobial resistance of Cronobacter strains was observed, which may imply a potential public health risk. Therefore, the surveillance of Cronobacter spp. in spices and cereals should be strengthened to improve epidemiological understandings of Cronobacter infections.

Keywords: Cronobacter spp., Multilocus sequence typing, serotyping, antimicrobial susceptibility, biofilm formation

Introduction

The Cronobacter genus, belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae, includes seven species: C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, C. dublinensis, C. muytjensii, C. turicensis, C. universalis, and C. condimenti (Iversen et al., 2008; Joseph et al., 2012). Among them, three species in the genus Cronobacter, including C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, and C. turicensis have been implicated in fatal neonatal infections resulting in sepsis, necrotizing enterocolitis and meningitis, with a high mortality rate and probability of neurological sequelae (Hunter and Bean, 2013; Ogrodzki and Forsythe, 2015). Although neonatal infections caused by Cronobacter spp. were highlighted, recent studies indicated that these bacteria can cause illness in both infants and adults, especially for newborns, the elderly, and individuals with weakened immune systems (Patrick et al., 2014; Alsonosi et al., 2015). Outbreaks of Cronobacter infections have been reported in many countries in recent years (Friedemann, 2009; Holý et al., 2014; Patrick et al., 2014).

The genus Cronobacter includes many ubiquitous species that are found in foodstuffs or raw materials, and clinical specimens as well as environmental samples (Reich et al., 2010; Alsonosi et al., 2015; Song et al., 2016; Brandão et al., 2017), but the exact reservoir and routes of transmission has still not been ascertained (Sani and Odeyemi, 2015). Understanding the transmission routes (e.g., waterborne, foodborne, or environmental) and vehicles (e.g., powdered infant formula, vegetables, meat, spices, or cereals) of a Cronobacter outbreak is of great public health importance. Thus, evaluation of a wide variety of foods might be necessary to reveal possible routes for transmission of infections caused by the genus Cronobacter.

Molecular typing techniques have become an important tool to study the genetic diversity of Cronobacter spp. and to trace individual strains that cause human infections. In recent years, a number of molecular typing techniques such as MLST (Baldwin et al., 2009), PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) (Vlach et al., 2017), pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (Lou et al., 2014), amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) (Turcovský et al., 2011), and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) (Drudy et al., 2006), have been established to differentiate these pathogens. Among these typing techniques, MLST is currently considered to be the best tool for epidemiological studies of Cronobacter spp. due to its high reproducibility and discriminatory ability. Serotyping is another important diagnosis tool widely used for identifying food-borne pathogens. Recent studies indicated that Cronobacter spp. have been differentiated into 17 serotypes by PCR-based O-antigen serotyping assays targeting the wzx (O-antigen flippase) and the wzy (O-antigen polymerase) genes (Jarvis et al., 2011, 2013; Sun et al., 2011, 2012a,b). The development of these molecular techniques is greatly helpful to distinguish Cronobacter species and may further assist in epidemiological investigation of outbreaks of Cronobacter infections.

Owing to the improper and abusive usage of antimicrobial agents, the emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant strains have become a serious threat to public health worldwide. Current studies indicated that Cronobacter spp. seemed to be less resistance to commonly used antibiotics compared to other foodborne pathogens such as Listeria monocytogenes, Campylobacter jejuni, and Salmonella spp. (Wang et al., 2013; Han et al., 2016; Komora et al., 2017). However, drug resistant strains of Cronobacter spp. were found in several studies (Lee et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2015; Fei et al., 2017), some of which were characterized as multidrug-resistant strains (Kilonzo-Nthenge et al., 2012). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the antibiotic resistance of Cronobacter spp. recovered from various food samples in order to classify the patterns of resistance and to formulate an effective strategy to prevent the potential spread of these strains.

In recent years, attachment and biofilm formation of foodborne pathogens has become a matter of increasing concern for food safety research because the high likelihoods of potential cross-contamination may lead to serious food safety problems (Simoes et al., 2010). Recently, some researchers have found that strains of Cronobacter spp. were able to form biofilms on many kinds of materials such as stainless steel, polyvinyl chloride, silicone, and polycarbonate (Jo et al., 2010; Park and Kang, 2014). Established biofilms are very difficult to remove due to the tolerance to sanitizing agents, and thereby pose a potential health risk to human health because microorganisms within biofilms might result in a persistent release of bacteria to foods and environment. The aim of the present study was to investigate the genetic diversity, by MLST and serotyping, the antimicrobial susceptibility, and biofilm formation of 40 Cronobacter isolates from spices and cereals.

Materials and methods

Strain collection, culture condition, and DNA extraction

A total of 40 Cronobacter isolates recovered from spices and cereal food samples in China between September 2014 and June 2015 were analyzed (Table 1). Twenty-one strains were from spices and 19 from cereals. These strains have been confirmed as Cronobacter spp. by genus specific PCR confirmation based on the outer membrane protein A (OmpA) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) gene, and 16S rRNA sequencing in our previous work (Li Y. H. et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017). The bacterial strains were routinely grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB; QingDao Hope Bio-technology Co., Ltd, Qingdao, China) at 37°C overnight without shaking. Then genomic DNA was extracted with the EZNA Genomic DNA Isolation Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Doraville, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Table 1.

Molecular identification and biofilm formation profiles of Cronobacter strains used in this study.

| Origin | Strain | IDa | fusA allele | fusA sequencing | STb | CC | Serotypec | Biofilm formation 595 nm | Biofilm formation category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPICES | |||||||||

| White pepper | XZCRO001 | 1705 | 148 | C. dublinensis | 498 | NF | 0.141 ± 0.012 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| White pepper | XZCRO002 | 1706 | 8 | C. sakazakii | 495 | Csak O1 | 0.142 ± 0.004 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| White pepper | XZCRO003 | 1707 | 18 | C. sakazakii | 136 | Csak O2 | 0.158 ± 0.012 | Weak | |

| White pepper | XZCRO004 | 1708 | 36 | C. sakazakii | 224 | Csak O7 | 0.141 ± 0.018 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Red pepper powder | XZCRO005 | 1709 | 20 | C. dublinensis | 522 | Cdub O1 | 0.145 ± 0.014 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Prickly ash powder | XZCRO006 | 1710 | 18 | C. sakazakii | 500 | Csak O7 | 0.143 ± 0.017 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Prickly ash powder | XZCRO007 | 1711 | 149 | C. sakazakii | 501 | NF | 0.174 ± 0.020 | Weak | |

| Prickly ash powder | XZCRO008 | 1712 | 26 | C. turicensis | 502 | Ctur O3 | 0.129 ± 0.007 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Dried bay leaves | XZCRO009 | 1713 | 22 | C. turicensis | 72 | 72 | Ctur O3 | 0.132 ± 0.003 | Non-biofilm producer |

| Chinese cinnamon | XZCRO010 | 1714 | 22 | C. turicensis | 72 | 72 | Ctur O3 | 0.134 ± 0.007 | Non-biofilm producer |

| Aniseed powder | XZCRO011 | 1715 | 7 | C. malonaticus | 504 | Cmal O2 | 0.171 ± 0.020 | Weak | |

| Prickly ash powder | XZCRO012 | 1716 | 68 | C. sakazakii | 143 | 143 | Csak O3 | 0.173 ± 0.010 | Weak |

| White pepper | XZCRO013 | 1717 | 144 | C. dublinensis | 570 | NF | 0.202 ± 0.021 | Weak | |

| Fennel | XZCRO014 | 1718 | 146 | C. universalis | 512 | Cuni O1 | 0.734 ± 0.034 | Strong | |

| Red pepper powder | XZCRO015 | 1719 | 147 | C. turicensis | 506 | NF | 0.142 ± 0.017 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Red pepper powder | XZCRO039 | 1743 | 67 | C. sakazakii | 148 | 16 | Csak O1 | 0.139 ± 0.010 | Non-biofilm producer |

| Cumin | XZCRO040 | 1744 | 67 | C. sakazakii | 148 | 16 | Csak O1 | 0.137 ± 0.015 | Non-biofilm producer |

| Black pepper | XZCRO041 | 1745 | 13 | C. malonaticus | 511 | Cmal O1 | 0.135 ± 0.017 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Prickly ash powder | XZCRO042 | 1746 | 17 | C. sakazakii | 158 | Csak O1 | 0.143 ± 0.012 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| CEREALS | |||||||||

| Mung bean flour | XZCRO016 | 1720 | 40 | C. malonaticus | 371 | NF | 0.145 ± 0.016 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Red bean flour | XZCRO017 | 1721 | 20 | C. dublinensis | 524 | Cdub O1 | 0.177 ± 0.030 | Weak | |

| Maize flour | XZCRO018 | 1722 | 40 | C. malonaticus | 371 | NF | 0.135 ± 0.003 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Soybean flour | XZCRO019 | 1723 | 17 | C. sakazakii | 158 | Csak O1 | 0.127 ± 0.004 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Buckwheat flour | XZCRO020 | 1724 | 12 | C. sakazakii | 17 | 17 | Csak O2 | 0.155 ± 0.006 | Weak |

| Proso millet | XZCRO021 | 1725 | 36 | C. sakazakii | 224 | Csak O7 | 0.126 ± 0.015 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Black soya bean | XZCRO022 | 1726 | 67 | C. sakazakii | 148 | 16 | Csak O1 | 0.123 ± 0.011 | Non-biofilm producer |

| Wheat flour | XZCRO023 | 1727 | 67 | C. sakazakii | 148 | 16 | Csak O1 | 0.175 ± 0.018 | Weak |

| Buckwheat flour | XZCRO024 | 1728 | 7 | C. malonaticus | 129 | 129 | Cmal O2 | 0.172 ± 0.009 | Weak |

| Mung bean flour | XZCRO025 | 1729 | 20 | C. dublinensis | 175 | NF | 0.140 ± 0.009 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Mung bean flour | XZCRO026 | 1730 | 1 | C. sakazakii | 4 | 4 | Csak O2 | 0.146 ± 0.005 | Non-biofilm producer |

| Glutinous rice | XZCRO027 | 1731 | 1 | C. sakazakii | 508 | Csak O2 | 0.147 ± 0.015 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Oatmeal flour | XZCRO028 | 1732 | 12 | C. sakazakii | 17 | 17 | Csak O2 | 0.129 ± 0.009 | Non-biofilm producer |

| Black rice | XZCRO029 | 1733 | 20 | C. dublinensis | 176 | Cdub O1 | 0.136 ± 0.010 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Maize flour | XZCRO030 | 1734 | 8 | C. sakazakii | 50 | Csak O1 | 0.129 ± 0.012 | Non-biofilm producer | |

| Wheat flour | XZCRO031 | 1735 | 18 | C. sakazakii | 136 | Csak O2 | 0.154 ± 0.008 | Weak | |

| Barley flour | XZCRO032 | 1736 | 8 | C. sakazakii | 68 | Csak O2 | 0.159 ± 0.005 | Weak | |

| Maize flour | XZCRO033 | 1737 | 1 | C. sakazakii | 509 | Csak O2 | 0.152 ± 0.003 | Weak | |

| Oatmeal flour | XZCRO034 | 1738 | 146 | C. universalis | 510 | Cuni O1 | 0.160 ± 0.005 | Weak | |

| Wheat flour | XZCRO035 | 1739 | 14 | C. sakazakii | 13 | 13 | Csak O2 | 0.146 ± 0.017 | Non-biofilm producer |

| Soybean flour | XZCRO043 | 1747 | 67 | C. sakazakii | 148 | 16 | Csak O1 | 0.381 ± 0.012 | Moderate |

| Negative control | 0.125 ± 0.008 | ||||||||

ID, Strain identification code in the Cronobacter PubMLST database.

Newly determined alleles and STs are in bold type.

NF, Not found.

Multilocus sequence typing and sequence analysis

MLST was performed by PCR amplification and sequencing of the fragments of typically 7 housekeeping genes (atpD, fusA, glnS, gltB, gyrB, inf B, and ppsA) (Baldwin et al., 2009). Alleles and STs were assigned in accordance with the Cronobacter MLST database website (http://pubmlst.org/cronobacter/). The fusA allele sequence analysis was also performed with the aim to identify and differentiate the isolates into species as previously described (Alsonosi et al., 2015; Brandão et al., 2017).

O-antigen serotype analysis

The serotypes of Cronobacter isolates obtained from spices and cereals in the present study were determined using the PCR-based O-antigen serotyping technique as previously described (Sun et al., 2012a,b; Jarvis et al., 2013). Primers and PCR cycling conditions used for serotyping of Cronobacter strains are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Lists of primers and PCR cycling conditions used for serotyping of Cronobacter strains.

| Serogroup | Target gene | Primer sequence | PCR cycling conditions | Amplicon size (bp) | References | No. of strains | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| spices | cereals | ||||||

| CsakO1 | wzy | CCCGCTTGTATGGATGTT | 95°C, 5 min; (94°C, 30 s; 53°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 30; 72°C, 7 min | 364 | Sun et al., 2012b | 4 | 5 |

| CTTTGGGAGCGTTAGGTT | |||||||

| CsakO2 | wzy | ATTGTTTGCGATGGTGAG | 95°C, 5 min; (94°C, 30 s; 53°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 30; 72°C, 7 min | 152 | Sun et al., 2012b | 1 | 8 |

| AAAACAATCCAGCAGCAA | |||||||

| CsakO3 | wzy | CTCTGTTACTCTCCATAGTGTTC | 95°C, 5 min; (94°C, 30 s; 53°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 30; 72°C, 7 min | 704 | Sun et al., 2012b | 0 | 1 |

| GATTAGACCACCATAGCCA | |||||||

| CsakO4 | wzy | ACTATGGTTTGGCTATACTCCT | 95°C, 5 min; (94°C, 30 s; 53°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 30; 72°C, 7 min | 890 | Sun et al., 2012b | 0 | 0 |

| ATTCATATCCTGCGTGGC | |||||||

| CsakO5 | wzy | GATGATTTTGTAAGCGGTCT | 95°C, 5 min; (94°C, 30 s; 53°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 30; 72°C, 7 min | 235 | Sun et al., 2012b | 0 | 0 |

| ACCTACTGGCATAGAGGATAA | |||||||

| CsakO6 | wzy | ATGGTGAAGGGAACGACT | 95°C, 5 min; (94°C, 30 s; 53°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 30; 72°C, 7 min | 424 | Sun et al., 2012b | 0 | 0 |

| ATCCCCGTGCTATGAGAC | |||||||

| CsakO7 | wzy | CCCGCTTGTATGGATGTT | 95°C, 5 min; (94°C, 30 s; 53°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 30; 72°C, 7 min | 364 | Sun et al., 2012b | 2 | 1 |

| CTTTGGGAGCGTTAGGTT | |||||||

| CmalO1 | wzx | AGGGGCACGGCTTAGTTCTGG | 95°C, 2 min; (95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 25; 72°C, 5 min | 323 | Jarvis et al., 2011 | 1 | 0 |

| CCCGCTTGCCCTTCACCTAAC | |||||||

| CmalO2 | wzx | TGGCCCTTGTTAGCAAGACGTTTC | 95°C, 2 min; (95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 25; 72°C, 5 min | 394 | Jarvis et al., 2011 | 1 | 1 |

| ATCCACATGCCGTCCTTCATCTGT | |||||||

| CdubO1 | wzx | TCGTTTTGATGCTCTCGCTGCG | 95°C, 2 min; (95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 25; 72°C, 5 min | 435 | Jarvis et al., 2013 | 1 | 2 |

| ACAAATCGCGTGCTGGCTTGAA | |||||||

| CdubO2 | wzx | CTCGGTTCATGGATTTGCGGC | 95°C, 2 min; (95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 25; 72°C, 5 min | 227 | Jarvis et al., 2013 | 0 | 0 |

| CAGCGTGAAAACAGCCAGGT | |||||||

| CturO1 | wzx | AGGGGCACGGCTTAGTTCTGG | 95°C, 2 min; (95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 25; 72°C, 5 min | 323 | Jarvis et al., 2013 | 0 | 0 |

| CCCGCTTGCCCTTCACCTAAC | |||||||

| CturO2 | wzy | TTTCTTGTTATTGCCTGTGT | 95°C, 5 min; (94°C, 30 s; 50°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x 30; 72°C, 5 min | 438 | Sun et al., 2012a | 0 | 0 |

| AACAAAATCAGCGAGACTAA | |||||||

| CturO3 | wzx | GCATCCCTTCAGAGTAGCGCA | 95°C, 2 min; (95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x25, 72°C, 5 min | 236 | Jarvis et al., 2013 | 3 | 0 |

| ACCACCTGCCATTGTCCTACTG | |||||||

| CuniO1 | wzx | CATTCTCGCTTCCGCAGTTGC | 95°C, 2 min; (95°C, 30 s; 55°C, 30 s; 72°C, 1 min) x25, 72°C, 5 min | 145 | Jarvis et al., 2013 | 1 | 1 |

| CCCAACCATCATTAGGGCCGAG | |||||||

| Uncertain | – | – | – | – | 4 | 3 | |

| Total | 21 | 19 | |||||

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Cronobacter strains was investigated by the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method using Mueller-Hinton agar (Hangzhou Microbial Reagent Co., Ltd, Hangzhou, China) according to the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2012). Thirteen antibiotics were tested: ampicillin (10 μg), ticarcillin-clavulanic acid (75:10 μg), cefixime (5 μg), amikacin (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), nitrofurantoin (300 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), meropenem (10 μg), aztreonam (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), trimethoprim (5 μg). All Cronobacter isolates and the two quality control strains (Escherichia coli ATCC 29522 and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213) were grown in nutrient agar plates (Hangzhou Microbial Reagent Co., Ltd, Hangzhou, China) at 37°C overnight during antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Biofilm formation assay

Microtiter plate assays (MPA) were performed to investigate the biofilm-forming ability of Cronobacter strains with minor modification, as previously described (Lee et al., 2012). Briefly, overnight cultures (1 ml) of Cronobacter strains (n = 40) were transferred to fresh TSB at 37°C for about 2 h in a shaking incubator. Subsequently, 200 μl of cell suspension (OD600 ≈ 0.3) was transferred into sterile 96-well flat bottom polystyrene microplates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA). The plates were incubated statically at 37°C for 48 h. Then the microtiter plates were gently washed three times with 250 μl of sterile distilled water and dried at room temperature. The biofilm was stained with 200 μl of 0.1% crystal violet solution for 30 min and washed three times with 250 μl sterile water. After drying, the crystal violet was liberated by 200 μl of 95% ethanol following 10 min incubation at room temperature. Finally, the sterile TSB was used as negative control and the optical density (OD) value of each well was measured at 595 nm with a microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). All the experiments were performed three times.

The cutoff OD (ODc) was defined as three standard deviations (SD) above the mean OD of the negative controls. Based on the ODc, the Cronobacter isolates were classified into four categories: (1) non-biofilm producers: OD of test isolate ≤ ODc; (2) weak biofilm producers: ODc < OD of test isolate ≤ (2 × ODc); (3) moderate biofilm producers: (2 × ODc) < of test isolate ≤ (4 × ODc); (4) strong biofilm producers: OD of test isolate > (4 × ODc).

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test was used to compare serotypes, antimicrobial susceptibility rates, or biofilm-formation abilities between Cronobacter isolates from spices and cereals. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 17.0 software package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Species identification

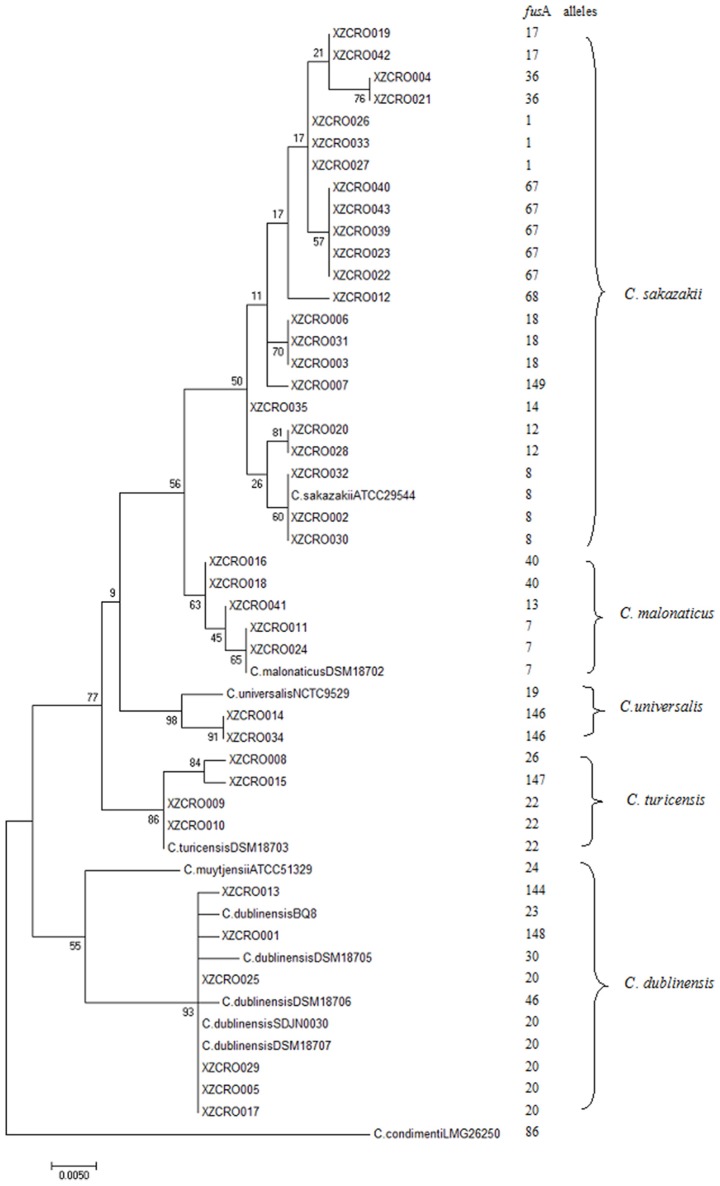

A total of 40 Cronobacter strains previously isolated from spices and cereal food samples were characterized by the fusA allele sequences analysis, and then all the allele sequences were submitted to the Cronobacter PubMLST database. A total of 21 fusA alleles (1, 7–8, 12–14, 17–18, 20, 22, 26, 36, 40, 67–68, 100, 144, and 146–149) were identified using the Cronobacter PubMLST database, four of which (146–149) were previously unreported (Table 1). Based on the fusA allele sequences analysis, a high diversity of Cronobacter species was observed, with five species of Cronobacter identified (Tables 1, 3). The most frequently observed isolates were C. sakazakii (n = 23), followed by C. dublinensis (n = 6), C. malonaticus (n = 5), C. turicensis (n = 4), and C. universalis (n = 2). No strains of C. muytjensii or C. condimenti were identified. The phylogenetic tree based on the fusA allele sequences demonstrates a very clear clustering across the genus Cronobacter with the 40 strains in five out of the seven species (Figure 1), which is in agreement with the results obtained from fusA allele sequences analysis.

Table 3.

Summary of fusA alleles, MLST sequence types, and serotypes among different Cronobacter species.

| Bacterial species | No. of strains | fusA allelesa | MLST sequence typesa | Serotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. sakazakii | 23 | 1, 8, 12, 14, 17, 18, 36, 67, 68, 149 | 4, 13, 17, 50, 68, 134, 136, 143, 148, 158, 224, 495, 500, 501, 508, 509 | CsakO1, CsakO2, CsakO3, CsakO7 |

| C. malonaticus | 5 | 7, 13, 22, 40 | 129, 371, 504, 511, | CmalO1, CmalO2 |

| C. dublinensis | 6 | 20, 100, 144, 148 | 175, 176, 498, 524, 570 | CdubO1 |

| C. turicensis | 4 | 22, 26, 147 | 72, 502, 506 | CturO3 |

| C. universalis | 2 | 146 | 510, 512 | CuniO1 |

New alleles and new STs are indicated in bold character.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood tree based on the fusA alleles (438 bp) for the differentiation of Cronobacter species in this study. This tree is drawn to scale using the ClustalX (V.2.0) and the MEGA (v.7.02) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Multilocus sequence typing

A total of 30 different STs among the 40 isolates were found, 14 (ST495, ST498, ST500-ST502, ST505, ST506-ST512, and ST570) of which were novel to the Cronobacter PubMLST database (Tables 1, 3). The most frequent STs in our study were ST148, identified five times, followed by ST17, ST72, ST136, ST158, ST224, ST371, and ST524 that included two isolates each, while the remaining 22 STs were identified only once. Of these frequent STs, the ST136, ST148, ST158, ST224, and ST524 were found in both spices and cereal samples; whereas ST17 and ST371 could only be found in cereal samples and ST72 found in spices samples. MLST assigned 12 isolates into 7 different CCs: CC4 (n = 1), CC13 (n = 1), CC16 (n = 1), CC17 (n = 1), CC72 (n = 1), CC129 (n = 1), and CC143 (n = 1), while the remaining 28 isolates were not assigned (Table 1).

Serotyping by PCR

Of the 40 Cronobacter isolates, 33 (82.5%) were clearly identified by PCR-based O-antigen serotyping methods, while seven (17.5%) isolates were undefined since O-antigen gene could not be amplified. O-antigen serotyping classified these strains into 9 serotypes: C. sakazakii serotype O1 (n = 9), C. sakazakii serotype O2 (n = 9), C. sakazakii serotype O3 (n = 1), C. sakazakii serotype O7 (n = 3), C. dublinensis O1 (n = 3), C. malonaticus O1 (n = 1), C. malonaticus O2 (n = 2), C. turicensis O3 (n = 3), and C. universalis O1 (n = 2) (Tables 1, 2).

The serotype distribution of isolates from spices and cereals is shown in Table 2. A significant difference in the distribution of Cronobacter serotypes was observed between spices and cereals (P < 0.05). Analysis of the relationship between serotypes and MLST profiles revealed a connection between ST and serotype. For example, all strains genotyped as C. sakazakii ST158 were identified as C. sakazakii serotype O1, and C. sakazakii ST148 identified as C. sakazakii serotype O2. In contrast, isolates of the same serotype but different STs were found in this study. For example, isolates belonging to ST50, ST148, ST158, and ST495 were characterized as C. sakazakii serotype O1. Similarly, isolates belonging to ST4, ST13, ST17, ST68, ST136, and ST509 were characterized as C. sakazakii serotype O2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

All of the 40 Cronobacter isolates were susceptible to 10 of the 13 antibiotic agents tested including ampicillin, cefixime, amikacin, gentamicin, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, nitrofurantoin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim, and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid. However, 70.0% (28/40) of the strains were resistant to ceftriaxone, among which 27.5% (11/40) of the strains were found in spices and 42.5% (17/40) of the strains were found in cereals. Besides ceftriaxone, 25.0% (10/40) of the strains were resistant to meropenem, eight (XZCRO006:ST500, XZCRO007:ST501, XZCRO011:ST504, XZCRO012:ST143, XZCRO013:ST570, XZCRO014:ST512, XZCRO015:ST506, and XZCRO042:ST158) of which were detected in spices, while the remaining 2 isolates (XZCRO019:ST158, and XZCRO020:ST17) in cereals. In addition, 2 isolates (XZCRO009:ST72, and XZCRO040:ST148) from spices and only 1 isolate (XZCRO027:ST508) from cereals were resistant to aztreonam (Table 4). No multidrug resistance (isolates resistant to three or more antimicrobial agents) strains were observed in both spices and cereals. Majority of Cronobacter isolates with the same ST showed a similar drug-resistance profile. However, isolates with the same ST sometimes showed different drug-resistance profile. For example, the 5 strains (XZCRO022, XZCRO023, XZCRO039, XZCRO040, and XZCRO043) of Cronobacter belonged to ST148, but only one strain was resistant to aztreonam (XZCRO040:ST148). When susceptibility results were compared according to their sources, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of antimicrobial resistance between isolates from spices and cereals for any of the agents tested (P > 0.05).

Table 4.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of the 40 Cronobacter strains recovered from spices and cereals by agar disc diffusion method.

| Antibiotic | No. of resistant strains (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Spices (n = 21) | Cereals (n = 19) | Total (n = 40) | |

| Ampicillin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cefixime | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Amikacin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gentamicin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tetracycline | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chloramphenicol | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trimethoprim | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ticarcillin-clavulanic acid | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aztreonam | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.5) | 3 (7.5) |

| Meropenem | 8 (20.0) | 2 (5.0) | 10 (25.0) |

| Ceftriaxone | 11 (27.5) | 17 (42.5) | 28 (70.0) |

Biofilm-formation ability of Cronobacter spp.

The biofilm-formation ability among the 40 isolates was detected by the MPA, and the results were shown in Table 1. Overall, a wide variation was found among the Cronobacter strains in the quantity of biofilm produced. The results indicated that 15 (37.5%) of the 40 tested isolates, belonging to 12 of the 30 previously identified STs, were capable to produce biofilm on polystyrene microtiter plates (Table 1). Using the proposed cutoff criteria, a cutoff value of 0.149 at OD595 nm was used to categorize the test strains as non-biofilm, weak, moderate, and strong biofilm producers. According to the result of microtiter plate test, one isolate belonging to ST512 scored as the most efficient biofilm producer, one isolate belonging to ST148 as moderate biofilm producer, and the other 13 isolates as weak biofilm producers (Table 1). However, no correlation between biofilm formation and STs was observed. Cronobacter strains identified as the same ST sometimes showed different biofilm-formation ability. For example, 5 strains (XZCRO22, XZCRO23, XZCRO39, XZCRO040, and XZCRO043) of Cronobacter were identified as ST148 in our study, only 1 of which (XZCRO043) was categorized as moderate biofilm producer, and 2 (XZCRO39 and XZCRO040) as weak biofilm producer, whereas the other 2 isolates (XZCRO22 and XZCRO23) were categorized as non-biofilm producers. In addition, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the amount of biofilm detected for Cronobacter spp. between spices and cereals.

Discussion

Cronobacter spp. have been isolated from many kinds of foodstuffs including plant materials such as vegetables, flours, herbs, and spices (Huang et al., 2015; Brandão et al., 2017), however the prevalence of Cronobacter spp. in such foodstuffs varied greatly among different studies. In a study of the prevalence of Cronobacter spp., these bacteria were detected in 26.7% (12/45) of herbs and spices in India (Singh et al., 2015). In another study, the prevalence of Cronobacter spp. was particularly low in spices samples (3.6%, 1/28) and dry cereals (4.9%, 6/123) in Netherlands (Kandhai et al., 2010). Cronobacter spp. was detected in herbs and spices, cereal mixes for children in Brazil (Brandão et al., 2017), where its prevalence was 36.7% (11/30) and 23.3% (7/30), respectively. In our previous studies, the overall prevalence of Cronobacter spp. in spices and cereals was determined to be 29.7% (19/64) (Li et al., 2017) and 21.0% (21/100) (Li Y. H. et al., 2016), respectively. However, in most of these studies, the MLST profiles of strains isolated from spices and cereals were not demonstrated. This study describes the genetic diversity, antimicrobial susceptibility, and biofilm formation of Cronobacter spp. recovered from spices and cereals in China during 2014–2015.

Based on the fusA sequence analysis, we found that the majority (57.5%) of Cronobacter isolates recovered from spices and cereals were C. sakazakii. The remaining strains were C. dublinensis (15.0%), C. malonaticus (12.5%), C. turicensis (20.0%), and C. universalis (5.0%). These findings are in agreement with previous studies which showed that C. sakazakii was the predominant Cronobacter species in different sources (Fei et al., 2015; Sulaiman et al., 2016; Brandão et al., 2017). Recent studies indicated that C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, and C. turicensis were the three pathovars of Cronobacter spp. that associated with several neonatal infections and adult infections (Hunter and Bean, 2013; Ogrodzki and Forsythe, 2015). Unfortunately, these three pathovars of Cronobacter spp. were identified from spices and cereals in this study. These results underline the importance of sanitary-hygienic and epidemiological surveillance in spices and cereals to reduce the risk of Cronobacter infections.

The application of MLST analysis of Cronobacter isolates would be helpful to better understanding the genetic diversity, virulence, and epidemiology of genus Cronobacter. In this study, a total of 40 Cronobacter strains were genotyped with the 7-loci MLST scheme. MLST analysis revealed 16, 4, 5, 3, and 2 STs in C. sakazakii, C. malonaticus, C. dublinensis, C. turicensis, and C. universalis, respectively (Table 3). This finding was in agreement with previous studies reporting that the majority of STs were identified in C. sakazakii (Xu et al., 2015; Brandão et al., 2017). At the time of writing (August 2017), the Cronobacter PubMLST database contained 2097 isolates and consisted of 609 defined STs, with 225 clinical isolates belonging to 53 STs. The most frequent STs of clinical relevance in the Cronobacter PubMLST database were C. sakazakii ST4 (88/225), followed by C. malonaticus ST7 (30/225) and C. sakazakii ST8 (14/225). Among the 30 STs identified in our study, only 5 STs (ST4, ST13, ST50, ST129, and ST158) were of clinical origin, with 4 (ST4, ST13, ST50, and ST158) and 1 (ST129) ST(s) for C. sakazakii, and C. malonaticus, respectively. Among these 5 STs we identified, ST158, corresponding to C. sakazakii, was found in both spice (prickly ash powder) and cereal (soybean flour) samples, while ST4, ST13, ST50, and ST129 could only be found in cereal samples from mung bean flour, wheat flour, maize flour, and buckwheat flour, respectively. These findings underline that spices and cereals can also be potential sources of Cronobacter infections, which might pose great risks to human health.

Recent studies indicated a strong association between C. sakazakii CC4 (such as ST4, ST 15, ST97, and etc.) and neonatal infections as well as C. malonaticus CC7 (such as ST 7, ST 84, ST 159, and etc.) and adult infections (Joseph and Forsythe, 2011; Hariri et al., 2013; Forsythe et al., 2014). Moreover, a goeBURST analysis of 1007 Cronobacter isolates performed in 2014 indicated that 19.4% (n = 195) and 5.7% (n = 58) of strains in the Cronobacter PubMLST database were C. sakazakii CC4 and C. malonaticus CC7, with 45.1% (88/195) and 56.9% (33/58) strains obtained from clinical sources, respectively (Forsythe et al., 2014). These findings remark the importance of surveillance of Cronobacter belonging to C. sakazakii CC4 and C. malonaticus CC7, which are the dominant pathovars of Cronobacter associated with neonatal, pediatric and adult infections. However, these two CCs are not only found in powdered infant formula and related products but also in many other kinds of foodstuffs. For instance, in a study of the prevalence of Cronobacter contamination in 90 samples of retail foods in Brazil, two strains isolated from maize flour were characterized as C. sakazakii CC4 (Brandão et al., 2017). In another study, 4 C. sakazakii CC4 isolates were recovered from rice flour, noodle and potable water, and 10 C. malonaticus CC7 isolates from rice flour, dried shrimp, chocolate, cookie, and potable water (Cui et al., 2014). In our study, only one C. sakazakii CC4 isolate was obtained from cereals, and no strains of C. malonaticus CC7 were found in both cereals and spices.

For serotyping, a total of nine serotypes were found among the 40 isolates, including nine serotypes from spices and six from cereals. Among the nine serotypes found, C. sakazakii serotype O1 (n = 9) and O2 (n = 9) were the most two frequently observed serotypes, which was in accordance with previous studies (Alsonosi et al., 2015; Fei et al., 2015). Most Cronobacter isolates (n = 33) were clearly serotyped in this study, except for 3, 2, 1, and 1 isolate(s) in C. dublinensis, C. malonaticus, C. sakazakii, and C. turicensis, respectively. Previous studies also suggested that serotyping of Cronobacter strains were sometimes uncertain. For instance, 51 Cronobacter strains were isolated from hospitalized patients, one of which (identified as C. muytjensii ST28) could not be determined when the PCR serotyping scheme was carried out (Alsonosi et al., 2015). In another study, a total of 111 Cronobacter isolates from Chinese ready-to-eat foods were serotyped based on the O-antigen serotyping, two of which (one identified as C. malonaticus and the other as C. dublinensis) were uncertain (Xu et al., 2015). The appearance of unidentified serotypes may be due to the high genetic diversity of Cronobacter spp., which may result in a failure determination when the serotyping methods were performed in such studies. Recently, Ogrodzki and Forsythe established a new capsular typing scheme based on sequencing of gnd and galE genes, which would be greatly helpful in distinguishing between Cronobacter species (Ogrodzki and Forsythe, 2015).

The increasing emergence of antibiotic resistant foodborne pathogens has been of great concern to public health in recent years. Results of the present study showed that frequency of antibiotic resistance in Cronobacter isolates recovered from spices and cereals was lower than strains of other foodborne pathogens such as L. monocytogenes, C. jejuni, and Salmonella spp. (Wang et al., 2013; Han et al., 2016; Komora et al., 2017). However, more attention should be paid to the inspection and control of strains of Cronobacter spp. because the resistance of these bacteria to many kinds of antimicrobial agents has been reported (Kilonzo-Nthenge et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014; Fei et al., 2017), even though the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles may vary in different studies performed in various samples collected from different locations.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed that the 40 isolates were susceptible to most antibiotics tested, except for ceftriaxone, meropenem, and aztreonam. Cephalosporins, the commonly used antimicrobial agents worldwide, were sometimes categorized into “generations” by their antimicrobial properties. The results of the present study suggested that a high resistance (70%) of Cronobacter spp. particularly C. sakazakii to ceftriaxone (third generation), whereas all isolates were sensitive to cefixime (third generation). Compared to our study, a little lower incidence (65%) of resistance to ceftriaxone was reported by Zhang et al. (2013) in imported dairy products; in contrast, antimicrobial resistance was not observed in another study performed by Li Z. et al. (2016) in retail milk-based infant and baby foods. Besides ceftriaxone, resistance of Cronobacter spp. to other cephalosporins, including cefazolin (first generation), cephalothin (first generation), and cefoxitin (second generation), has been reported in Iraq (Mossawi and Joubori, 2015) and UK (Gosney, 2008). The different performance of antimicrobial resistance on Cronobacter spp. among various cephalosporins might be due to extensive use or misuse of these antimicrobial agents which increased drug resistance of these bacteria. In our study, a total of 10 (25%) Cronobacter isolates were resistant to meropenem; in contrast, all of the tested isolates from dairy products including powdered infant formula in China, Iraq, and Japan were susceptible to meropenem (Oonaka et al., 2010; Pan et al., 2014; Li Z. et al., 2016). Apart from isolates originating from food, several clinical isolates were found susceptible to meropenem in Taiwan (Tsai et al., 2013).

In contrast to previous studies whereas resistance of Cronobacter spp. to ampicillin has been reported (Oonaka et al., 2010; Li et al., 2014; Fei et al., 2017), ampicillin-resistant strains were not found in this study. Besides ampicillin, Cronobacter isolates showed 100% susceptibility to tetracycline, ciprofloxacin and chloramphenicol, whereas the other researchers reported a high resistance of Cronobacter spp. to these antibiotics (Kilonzo-Nthenge et al., 2012). In one study conducted in the USA, high resistance of C. sakazakii isolated from domestic kitchens to tetracycline (66.6% of isolates) and ciprofloxacin (57.1%) was observed. In another study in South Korea, Lee et al. (2012) reported that 3.4 and 1.8% of Cronobacter isolates recovered from various types of foods were resistant to chloramphenicol and tetracycline, respectively.

In the present study, 37.5% of the Cronobacter isolates from spices and cereals were able to form biofilm on polystyrene surfaces; however majority of these isolates (32.5%) were weak biofilm producers and less were moderate (2.5%) or strong (2.5%) biofilm producers. Similar results have been reported earlier in Mexico wherein 26% of Cronobacter spp. was capable of forming biofilms (Cruz et al., 2011). In contrast, a high proportion of biofilm-producing isolates of Cronobacter spp. recovered from various food in South Korea was observed (Lee et al., 2012). Differences in biofilm formation between various Cronobacter isolates could be due to strain variations that recovered from different sources and geographical locations. Moreover, the capacity of biofilm formation of Cronobacter strains is generally influenced by environmental conditions such as culture media and carbon source, and storage humidity levels (Jung et al., 2013).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated a high genetic diversity of Cronobacter isolates recovered from spices and cereals, providing useful information on molecular epidemiology of Cronobacter infections. MLST analysis revealed that C. sakazaki was the most common species recovered from spices and cereals, followed by C. dublinensis C. malonaticus, C. turicensis, and C. universalis. The presence of isolates of clinical relevance including C. sakazakii ST4 (CC4) revealed that spices and cereals are likely to be the potential sources for human infection with Cronobacter spp. Although most Cronobacter strains were susceptible to the antimicrobial agents used in this study, further studies on the antimicrobial resistance of these foodborne pathogens are important to ensure effective treatment of human infections caused by Cronobacter spp.

Author contributions

YL and JS: Contributed to the conception of the study; YL and HY: Wrote the manuscript; YL and YZ: Analyzed and interpreted the data; YL, HJ, and YJ: Conducted the experiments; Each author substantially contributed to the work reported here.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31401595), the Scientific Research Foundation for Excellent Talents of Xuzhou Medical College (D2014002), and a project funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

References

- Alsonosi A., Hariri S., Kajsík M., Oriešková M., Hanulík V., Röderová M., et al. (2015). The speciation and genotyping of Cronobacter isolates from hospitalised patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34, 1979–1988. 10.1007/s10096-015-2440-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin A., Loughlin M., Caubilla-Barron J., Kucerova E., Manning G., Dowson C., et al. (2009). Multilocus sequence typing of Cronobacter sakazakii and Cronobacter malonaticus reveals stable clonal structures with clinical significance which do not correlate with biotypes. BMC Microbiol. 9:223. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandão M. L. L., Umeda N. S., Jackson E., Forsythe S. J., de Filippis I. (2017). Isolation, molecular and phenotypic characterization, and antibiotic susceptibility of Cronobacter spp. from Brazilian retail foods. Food Microbiol. 63, 129–138. 10.1016/j.fm.2016.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). (2012). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Second Informational Supplement M100-S22. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz A., Xicohtencatl-Jones J., González-Pedrajo B., Bobadilla M., Eslava C., Rosas I. (2011). Virulence traits in Cronobacter species isolated from different sources. Can. J. Microbiol. 57, 735–744. 10.1139/w11-063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J. H., Du X. L., Liu H., Hu G. C., Lv G. P., Xu B. H., et al. (2014). The genotypic characterization of Cronobacter spp. isolated in China. PLoS ONE 9:e102179. 10.1371/journal.pone.0102179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drudy D., O'Rourke M., Murphy M., Mullane N. R., O'Mahony R., Kelly L., et al. (2006). Characterization of a collection of Enterobacter sakazakii isolates from environmental and food sources. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 110, 127–134. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei P., Jiang Y. J., Feng J., Forsythe S. J., Li R., Zhou Y. H., et al. (2017). Antibiotic and desiccation resistance of Cronobacter sakazakii and C. malonaticus isolates from powdered infant formula and processing environments. Front. Microbiol. 8:316. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei P., Man C., Lou B., Forsythe S. J., Chai Y. L., Li R., et al. (2015). Genotyping and source tracking of Cronobacter sakazakii and C. malonaticus isolates from powdered infant formula and an infant formula production factory in China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 5430–5439. 10.1128/AEM.01390-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe S. J., Dickins B., Jolley K. A. (2014). Cronobacter, the emergent bacterial pathogen Enterobacter sakazakii comes of age; MLST and whole genome sequence analysis. BMC Genomics 15:1121. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann M. (2009). Epidemiology of invasive neonatal Cronobacter (Enterobacter sakazakii) infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28, 1297–1304. 10.1007/s10096-009-0779-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosney M. (2008). Enterobacter sakazakii bacteraemia with multiple splenic abscesses in a 75-year-old woman: a case report. Age Ageing 37, 236–238. 10.1093/ageing/afn006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. F., Zhu D. M., Lai H. M., Zeng H., Zhou K., Zou L. K., et al. (2016). Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance profiling and genetic diversity of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from broilers at slaughter in China. Food Control 69, 160–170. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.04.051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri S., Joseph S., Forsythe S. J. (2013). Cronobacter sakazakii ST4 strains and neonatal meningitis, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 175–177. 10.3201/eid1901.120649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holý O., PetrŽelová J., Hanulík V., Chromá M., Matoušková I., Forsythe S. J. (2014). Epidemiology of Cronobacter spp. isolates from patients admitted to the Olomouc University Hospital (Czech Republic). Epidemiol. Mikrobiol. Imunol. 63, 69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Pang Y. H., Wang H., Tang Z. Z., Zhou Y., Zhang W. Y., et al. (2015). Occurrence and characterization of Cronobacter spp. in dehydrated rice powder from Chinese supermarket. PLoS ONE 10:e0131053. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C. J., Bean J. F. (2013). Cronobacter: an emerging opportunistic pathogen associated with neonatal meningitis, sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Perinatol. 33, 581–585. 10.1038/jp.2013.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen C., Mullane N., Mccardell B., Tall B. D., Lehner A., Fanning S., et al. (2008). Cronobacter gen. nov., a new genus to accommodate the biogroups of Enterobacter sakazakii, and proposal of Cronobacter sakazakii gen. nov., comb. nov., Cronobacter malonaticus sp. nov., Cronobacter turicensis sp. nov., Cronobacter muytjensii sp. nov., Cronobacter dublinensis sp. nov., Cronobacter genomospecies 1, and of three subspecies, Cronobacter dublinensis subsp. dublinensis subsp. nov., Cronobacter dublinensis subsp. lausannensis subsp. nov. and Cronobacter dublinensis subsp. lactaridi subsp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micriobol. 58, 1442–1447. 10.1099/ijs.0.65577-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis K. G., Grim C. J., Franco A. A., Gopinath G., Sathyamoorthy V., Hu L., et al. (2011). Molecular characterization of Cronobacter lipopolysaccharide O-antigen gene clusters and development of serotype-specific PCR assays. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4017–4026. 10.1128/AEM.00162-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis K. G., Yan Q. Q., Grim C. J., Power K. A., Franco A. A., Hu L., et al. (2013). Identification and characterization of five new molecular serogroups of Cronobacter spp. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10, 343–352. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S. H., Baek S. B., Ha J. H., Ha S. D. (2010). Maturation and survival of Cronobacter biofilms on silicone, polycarbonate, and stainless steel after UV light and ethanol immersion treatments. J. Food. Prot. 73, 952–956. 10.4315/0362-028X-73.5.952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S., Cetinkaya E., Drahovska H., Levican A., Figueras M. J., Forsythe S. J. (2012). Cronobacter condimenti sp nov., isolated from spiced meat, and Cronobacter universalis sp nov., a species designation for Cronobacter sp genomospecies 1, recovered from a leg infection, water and food ingredients. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Micriobiol. 62, 1277–1283. 10.1099/ijs.0.032292-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph S., Forsythe S. J. (2011). Predominance of Cronobacter sakazakii sequence type 4 in neonatal infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 1713–1715. 10.3201/eid1709.110260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. H., Choi N. Y., Lee S. Y. (2013). Biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide (EPS) production by Cronobacter sakazakii depending on environmental conditions. Food Microbiol. 34, 70–80. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandhai M. C., Heuvelink A. E., Reij M. W., Beumer R. R., Dijk R., van Tilburg J. J. H. C., et al. (2010). A study into the occurrence of Cronobacter spp. in the Netherlands between 2001 and 2005. Food Control 21, 1127–1136. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.01.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kilonzo-Nthenge A., Rotich E., Godwin S., Nahashon S., Chen F. (2012). Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Cronobacter sakazakii isolated from domestic kitchens in middle Tennessee, United States. J. Food Prot. 75, 1512–1517. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komora N., Bruschi C., Magalhães R., Ferreira V., Teixeira P. (2017). Survival of Listeria monocytogenes with different antibiotic resistance patterns to food-associated stresses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 245, 79–87. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. D., Park J. H., Chang H. (2012). Detection, antibiotic susceptibility and biofilm formation of Cronobacter spp. from various foods in Korea. Food Control 24, 225–230. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.09.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Chen Q. M., Zhao J. F., Jiang H., Lu F. X., Bie X. M., et al. (2014). Isolation, identification and antimicrobial resistance of Cronobacter spp. isolated from various foods in China. Food Control 37, 109–114. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.09.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Jiang H., Jiao Y., Xu W., Zou X. Q., Pei S. F. (2017). Isolation and identification of Cronobacter spp. from dried spices and condiments. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 38, 125–130. 10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2017.19.024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Zhang Y. F., Zhang Q. C., Xu W., Zou X. Q., Pei S. F., et al. (2016). Isolation and identification of Cronobacter spp. from cereal foods. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 37, 154–158, 164. 10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2016.15.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Ge W., Li K., Gan J., Zhang Y., Zhang Q., et al. (2016). Prevalence and characterization of Cronobacter sakazakii in retail milk-based infant and baby foods in Shaanxi, China. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 13, 221–227. 10.1089/fpd.2015.2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou X. Q., Si G. J., Yu H., Qi J. J., Liu T., Fang Z. G. (2014). Possible reservoir and routes of transmission of Cronobacter (Enterobacter sakazakii) via wheat flour. Food Control 43, 258–262. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.03.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mossawi M. A., Joubori Y. H. (2015). Detection of Cronobacter sakazakii (Enterobacter sakazakii) in powdered food infants (PIF) and raw milk in Iraq. Baghdad Sci. J. 12, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodzki P., Forsythe S. (2015). Capsular profiling of the Cronobacter genus and the association of specific Cronobacter sakazakii and C. malonaticus capsule types with neonatal meningitis and necrotizing enterocolitis. BMC Genomics 16:758. 10.1186/s12864-015-1960-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oonaka K., Furuhata K., Hara M., Fukuyama M. (2010). Powder infant formula milk contaminated with Enterobacter sakazakii. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 63, 103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z., Cui J., Lyu G., Du X., Qin L., Guo Y., et al. (2014). Isolation and molecular typing of Cronobacter spp. in commercial powdered infant formula and follow-up formula. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 11, 456–461. 10.1089/fpd.2013.1691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. H., Kang D. H. (2014). Fate of biofilm cells of Cronobacter sakazakii under modified atmosphere conditions. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 57, 782–784. 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.01.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick M. E., Mahon B. E., Greene S. A., Rounds J., Cronquist A., Wymore K., et al. (2014). Incidence of Cronobacter spp. infections, United States, 2003-2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 1520–1523. 10.3201/eid2009.140545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich F., König R., von Wiese W., Klein G. (2010). Prevalence of Cronobacter spp. in a powdered infant formula processing environment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 140, 214–217. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sani N. A., Odeyemi O. A. (2015). Occurrence and prevalence of Cronobacter spp. in plant and animal derived food sources: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Springerplus 4:545. 10.1186/s40064-015-1324-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoes M., Simoes L. C., Vieira M. J. (2010). A review of current and emergent biofilm control strategies. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 43, 573–583. 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.12.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N., Goel G., Raghav M. (2015). Prevalence and characterization of Cronobacter spp. from various foods, medicinal plants, and environmental samples. Curr. Microbiol. 71, 31–38. 10.1007/s00284-015-0816-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Shukla S., Lee G., Park S., Kim M. (2016). Detection of Cronobacter genus in powdered infant formula by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assayusing anti-Cronobacter antibody. Front. Microbiol. 7:1124. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman I. M., Jacobs E., Segars K., Simpson S., Kerdahi K. (2016). Genetic characterization of Cronobacter sakazakii recovered from the environmental surveillance samples during a sporadic case investigation of foodborne illness. Curr. Microbiol. 73, 273–279. 10.1007/s00284-016-1059-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Arbatsky N. P., Wang M., Shashkov A. S., Liu B., Wang L., et al. (2012a). Structure and genetics of the O-antigen of Cronobacter turicensis G3882 from a new serotype, C. turicensis O2, and identification of a serotype-specific gene. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 66, 323–333. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.01013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Wang M., Liu H., Wang J., He X., Zeng J., et al. (2011). Development of an O-antigen serotyping scheme for Cronobacter sakazakii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2209–2214. 10.1128/AEM.02229-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Wang M., Wang Q., Cao B., He X., Li K., et al. (2012b). Genetic analysis of the Cronobacter sakazakii O4 to O7 O-antigen gene clusters and development of a PCR assay for identification of all C. sakazakii O serotypes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 3966–3974. 10.1128/AEM.07825-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. Y., Liao C. H., Huang Y. T., Lee P. I., Hsueh P. R. (2013). Cronobacter infections not from infant formula, Taiwan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 19, 167–169. 10.3201/eid1901.120774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turcovský I., Kuniková K., Drahovská H., Kaclíková E. (2011). Biochemical and molecular characterization of Cronobacter spp. (formerly Enterobacter sakazakii) isolated from foods. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 99, 257–269. 10.1007/s10482-010-9484-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlach J., Javurková B., Karamonová L., BlaŽková M., Fukal L. (2017). Novel PCR-RFLP system based on rpoB gene for differentiation of Cronobacter species. Food Microbiol. 62, 1–8. 10.1016/j.fm.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. H., Ye K. P., Wei X. R., Cao J. X., Xu X. L., Zhou G. H. (2013). Occurrence, antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation of Salmonella isolates from a chicken slaughter plant in China. Food Control 33, 378–384. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.03.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Li C., Wu Q., Zhang J., Huang J., Yang G. (2015). Prevalence, molecular characterization, and antibiotic susceptibility of Cronobacter spp. in Chinese ready-to-eat foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 204, 17–23. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. M., Zeng J., Wei H. Y., Fu P. B., Han X. (2013). Study on antibiotic resistance of Cronobacter sakazakii isolated from imported dairy product. Chin. J. Food Hyg. 25, 320–323. 10.13590/j.cjfh.2013.04.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]