Abstract

Background

Increasingly, patients with multiple colorectal liver metastases (CLM) are surgically treated. Some studies have shown that patients with bilobar and unilobar multiple CLM have similar outcomes, but other have shown that patients with bilobar CLM have worse outcomes after resection. We aimed to compare clinical outcomes of surgical treatment of bilobar and unilobar CLM using propensity score matching.

Methods

The single-institution study included patients who underwent hepatectomy for ≥3 histologically confirmed CLM during 1998–2014. Clinicopathologic characteristics and long-term outcomes were compared between patients with bilobar and unilobar CLM in a propensity-score-adjusted cohort.

Results

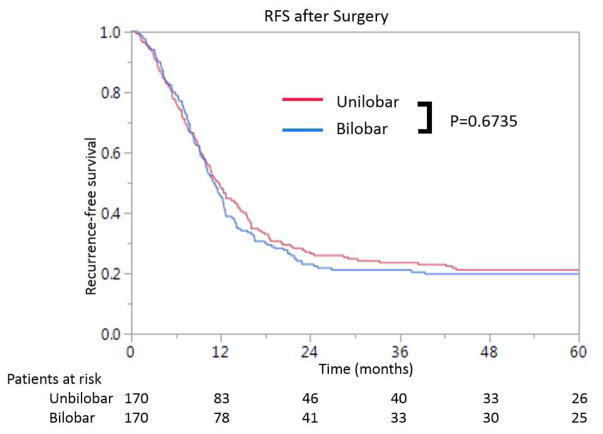

A total of 473 patients met the inclusion criteria, 271 (57%) with bilobar and 202 (43%) with unilobar CLM. In the propensity-score-matched population (bilobar, 170; unilobar, 170), no differences were observed according to the distribution of CLM except for a greater frequency of concomitant ablation, and R1 resection in the bilobar group. There was no difference between the bilobar and unilobar groups in 5-year overall survival rates (46% and 49%, respectively; P=0.740) or 3-year recurrence-free survival rates (21% and 24%, respectively; P=0.674).

Conclusions

Tumor distribution may not affect the curability of surgery for multiple CLM. Liver resection would be justified for selected patients with bilobar CLM.

Keywords: colorectal liver metastases, bilobar, liver resection, overall survival, recurrence-free survival

INTRODUCTION

In the early 1990s, when resection of colorectal liver metastases (CLM) became a standard practice, patients with more than 3 lesions were excluded.[1] Now, however, thanks to advances in patient selection, systemic therapy, and liver resectional techniques,[2] the presence of multiple lesions is no longer a contraindication to surgery for CLM.[3] Hepatic resection combined with perioperative chemotherapy has become the standard of care for patients with multiple CLM.[4]

Resection of bilobar multiple CLM remains a challenge because it can be difficult to achieve margin-negative resection while preserving sufficient functional liver parenchyma to avoid postoperative hepatic insufficiency.[5] In the current era of multimodality treatment, some reports indicate that bilobar CLM are associated with a poor prognosis after resection.[6–11] However, with advanced surgical techniques and strategies (e.g., portal vein embolization, 2-stage hepatectomy and/or liver-first sequencing), an increasing number of patients with bilobar CLM have undergone curative surgical resection.[5, 12–14] Some reports show that tumor distribution (bilobar or unilobar) does not influence the long-term outcome of patients with multiple CLM.[15–20]

Primary lymph node metastasis, number of CLM, and diameter of largest metastasis have been reported to be prognostic factors in patients with CLM,[21–23] and the number of CLM has been reported to be a particularly strong prognostic factor.[24] However, the impact of tumor distribution on prognosis has varied among studies,[6–11, 15–20] and no previous reports have had sufficient sample size to accurately evaluate the impact of tumor distribution on curability or prognosis. Hence, it is controversial whether bilobar distribution in itself is a poor prognostic factor or not.

Within this context, the primary aim of this study was to compare outcomes of surgically treated patients with bilobar CLM versus unilobar CLM using propensity score matching analysis

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population and Review of Patient Records

Approval of the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center was obtained for this retrospective study (PA17-0394). From a prospectively maintained database, we identified 1971 consecutive patients who underwent liver resection for histologically confirmed CLM during the period from January 1998 through November 2014. Patients who underwent repeat hepatectomy for recurrence (n=280), patients who did not undergo primary tumor resection or second-stage hepatectomy (n=75), patients without at least 2 years of follow-up after hepatectomy (n=205), and patients with fewer than 3 tumors (n=938) were excluded, resulting in a final cohort of 473 patients (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

All patients were evaluated preoperatively with a baseline history and physical examination. Decisions about treatment were made collectively at a multidisciplinary liver tumor conference. Following preoperative chemotherapy, patients underwent re-staging, and surgical resection was offered to those patients whose tumors were considered resectable, defined as ability to achieve a negative margin while preserving more than 20% to 30% of the total estimated liver volume, sparing 2 continuous hepatic segments, and maintaining vascular inflow and outflow and biliary drainage.[25] In patients with an anticipated insufficient standardized future liver remnant, preoperative portal vein embolization and staged hepatectomy were performed.[14] When it was not possible to design a resection that would permit complete tumor resection while leaving sufficient vascularized hepatic parenchyma to support postoperative hepatic function, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) combined with resection was performed.[26, 27]

The following data were recorded from the electronic medical record: sex, age, diagnosis, preoperative chemotherapy cycles and regimens, perioperative outcomes (estimated blood loss, blood transfusion, operative time, and surgical procedure), tumor characteristics (number of CLM and size of largest metastasis), and rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (RAS) mutation status. Postoperative complications were reviewed and classified according to the Clavien-Dindo classification. Complications classified as class IIIa or higher were defined as major.[28] Postoperative hepatic insufficiency was defined as a postoperative peak total bilirubin level in serum greater than 7 mg/dL.[29] Death from liver failure was calculated at 90 days after surgical resection or during the index admission.

Statistical Analyses

Propensity scores were calculated as the single composite variable from a non-parsimonious multivariate logit-linked binary logistic regression of the baseline characteristics. Bilobar vs. unilobar CLM was the dependent variable.[30, 31] The matching algorithm was based on logistic regression and included the following clinically relevant covariates: sex, age, body mass index, primary tumor site (colon or rectum), primary tumor lymph node status, time from primary diagnosis to CLM diagnosis, RAS status, number of CLM, and size of largest metastasis. Carcinoembryonic antigen level was not part of the propensity scores because of a large number of missing variables before preoperative chemotherapy. The matching procedure was performed as follows. First, caliper matching of the propensity score was applied with caliper size predefined as 0.2 of the standard deviation of the total sample. In a 1-pass procedure starting with a given patient with bilobar CLM, the closest match of a patient with unilobar CLM was identified. Next, covariates for bilobar vs. unilobar were compared. If covariates were equivalent or varied ≤10%, the pair of patients was retained for analysis and removed from the total sample to allow for the next matching cycle to take place. If covariates varied >10%, the pair was rejected. Then the first step of the matching process was repeated to identify the next closest match to the patient of the failed match according to the propensity score. Subsequently, a 1-to-1 match between the bilobar and unilobar groups was performed by the nearest-neighbor matching method within 0.2 standard deviations.

Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of hepatic resection to the date of death or last follow-up. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was measured from the date of hepatic resection to the date of radiographic detection of recurrence or last follow-up. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. All test were 2-sided, and P<0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed with JMP software (version 12.1.0; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of the 473 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 271 (57%) had bilobar CLM, and 202 (43%) had unilobar CLM (Fig. 1). The median follow-up time for all patients was 43.6 months including 41.7 months for the patients with bilobar CLM and 49.6 months for the patients with unilobar CLM. Clinicopathologic characteristics and perioperative data are summarized in Table 1 according to the distribution of the CLM. Fifty patients with bilobar CLM (18%) underwent 2-stage resection. Before propensity score matching, patients with bilobar CLM had a greater mean number of tumors and a larger maximum tumor diameter and were more likely to have primary tumor lymph node metastases, have undergone combined resection requiring RFA and experience an R1 (<1mm margin) resection compared to patients with unilobar CLM. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups with respect to preoperative chemotherapy or RAS status. Postoperative liver insufficiency occurred in 3 patients with bilobar CLM and 3 patients with unilobar CLM (P=0.718).

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic characteristics and perioperative outcomes in patients with unilobar and bilobar colorectal liver metastases (CLM)*

| Characteristic or outcome | Unilobar CLM | Bilobar CLM | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 202 | 271 | |

| Sex, M: F | 121: 81 | 155: 116 | 0.555 |

| Age, median (range), y | 56 (23–86) | 54 (18–79) | 0.196‡ |

| Body mass index, median (range), kg/m2 | 27.7 (16.4–47.0) | 27.0 (18.0–45.8) | 0.381‡ |

| Rectal primary tumor | 35 (17) | 49 (18) | 0.423 |

| Primary tumor lymph node metastasis | 130 (64) | 198 (73) | 0.043 |

| Synchronous CLM / Metachronous CLM | 113 (56) | 165 (61) | 0.280 |

| RAS status, wild-type/mutation/ unknown | 65/44/93 | 98/76/97 | 0.070 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 175 (87) | 243 (90) | 0.311 |

| ≥7 cycles | 76 (38) | 99 (37) | 0.808 |

| Use of bevacizumab | 113 (56) | 171 (63) | 0.116 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen level, median (range), ng/dl | 4.1 (0.5–1304) | 4.0 (0.5–7000) | 0.432‡ |

| Number of tumors, median (range) | 3 (3–30) | 5 (3–41) | <0.0001‡ |

| Size of largest metastasis, median (range), mm | 30 (4–150) | 25 (2–115) | 0.003‡ |

| Preoperative portal vein embolization | 32 (16) | 38 (14) | 0.582 |

| Major resection (≥ 3 Couinaud segments) | 162 (80) | 207 (76) | 0.320 |

| Resection with RFA | 1 (0.5) | 108 (40) | <0.0001 |

| Estimated blood loss ≥ 1000 g | 16 (8) | 14 (5) | 0.227 |

| Blood transfusion | 14 (7) | 13 (5) | 0.319 |

| Operative time ≥ 300 min | 48 (24) | 66 (24) | 0.882 |

| Major morbidity$ | 26 (13) | 31 (11) | 0.776 |

| Surgical margin status, R0: R1¥ | 195: 7 | 237: 34 | 0.002 |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 152 (75) | 192 (71) | 0.287 |

RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

Values in table are number of patients (percentage) unless indicated otherwise.

χ2 test, unless indicated otherwise.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Complication classified as Clavien-Dindo class IIIa or higher.

R0, no tumor cells <1 mm from the margin; R1, tumor cells <1 mm from the margin.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics after Propensity Score Matching

A total of 170 patients with bilobar CLM were matched with 170 patients with unilobar CLM. Clinicopathologic characteristics after the propensity score matching are summarized in Table 2. Although the propensity score matching significantly reduced standardized differences for most observed covariates, resulting in a substantial improvement in the covariate balance, the median number of CLM remained higher for patients with bilobar CLM (median 4 lesions) than for those with unilobar CLM (median 3 lesions) (P=0.016). However, the minimum (3 lesions) and the range (3–15) were similar between the groups.

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of patients with unilobar and bilobar colorectal liver metastases (CLM) after propensity score matching*

| Characteristic | Unilobar CLM | Bilobar CLM | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 170 | 170 | — |

| Sex, M: F | 96: 74 | 101: 69 | 0.583 |

| Age, median (range), y | 55 (23–86) | 55 (18–79) | 0.880‡ |

| Body mass index, median (range), kg/m2 | 27.8 (16.4–47.0) | 27.2 (18.0–45.8) | 0.671‡ |

| Rectal primary tumor | 33 (19) | 31 (18) | 0.781 |

| Primary tumor lymph node metastasis | 118 (69) | 116 (68) | 0.815 |

| Synchronous CLM / Metachronous CLM | 104 (61) | 93 (55) | 0.227 |

| RAS status, wild-type/mutation/ unknown | 53/39/78 | 58/37/75 | 0.933 |

| Preoperative chemotherapy | 151 (89) | 146 (86) | 0.414 |

| ≥7 cycles | 65 (38) | 62 (36) | 0.737 |

| Use of bevacizumab | 98 (58) | 92 (54) | 0.512 |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen level, median (range), ng/dl | 3.4 (0.5–1304) | 4.4 (0.5–3693) | 0.104‡ |

| Number of tumors, median (range) | 3 (3–15) | 4 (3–15) | 0.016‡ |

| Size of largest metastasis, median (range), mm | 25 (4–100) | 26 (2–95) | 0.656‡ |

Values in table are number of patients (percentage) unless indicated otherwise.

χ2 test, unless indicated otherwise.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Survival and Perioperative Characteristics after Propensity Score Matching

After propensity score matching, the median OS in the patients with bilobar CLM was 55.0 months (95% CI: 45.6–70.2) and the median OS in the patients with unilobar CLM was 57.7 months (95% CI: 49.0–80.0). Cumulative 3- and 5-year OS rates were 70% and 46%, respectively, in the patients with bilobar CLM, compared to 68% and 49%, respectively, in the patients with unilobar CLM(P=0.740) (Fig. 2A). The median RFS in the patients with bilobar CLM was 11.1 months (95% CI: 9.8–12.4) and the median RFS in the patients with unilobar CLM was 11.7 months (95% CI: 9.7–14.3). Cumulative 1- and 3-year RFS rates were 45% and 21%, respectively, in the patients with bilobar CLM, compared to 48% and 24%, respectively, in the patients with unilobar CLM (P=0.674) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Cumulative overall survival (A) and recurrence-free survival (B) in patients with multiple colorectal liver metastases (CLM) undergoing resection according to distribution of CLM after propensity score matching.

Perioperative characteristics and site of recurrence after the propensity score matching are shown in Table 3. Eleven patients with bilobar CLM (6%) underwent 2-stage resection. Patients with bilobar CLM were more likely than patients with unilobar CLM to require concomitant RFA (P<0.0001) and have R1 resection (P=0.007). Postoperative liver insufficiency occurred in 2 patients with bilobar CLM and 3 patients with unilobar CLM (P=0.651). Only 1 patient, with bilobar CLM, died of liver failure within 90 days after surgical resection. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups with respect to hepatic vs. extrahepatic site of recurrence.

Table 3.

Perioperative characteristics of patients with unilobar and bilobar colorectal liver metastases (CLM) after propensity score matching*

| Outcome | Unilobar CLM | Bilobar CLM | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 170 | 170 | |

| Preoperative portal vein embolization | 25 (15) | 20 (12) | 0.423 |

| Major resection (≥ 3 Couinaud segments) | 136 (80) | 120 (71) | 0.044 |

| Resection with RFA | 1 (1) | 86 (51) | <0.0001 |

| Estimated blood loss ≥ 1000 g | 13 (8) | 7 (4) | 0.163 |

| Blood transfusion | 11 (7) | 10 (6) | 0.811 |

| Operative time ≥ 300 min | 40 (24) | 41 (24) | 0.899 |

| Major morbidity$ | 22 (13) | 22 (14) | 0.862 |

| Surgical margin status, R0: R1¥ | 165: 5 | 153: 17 | 0.007 |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | 129 (76) | 133 (78) | 0.606 |

| Site of recurrence | |||

| Liver only | 52 (31) | 52 (31) | 0.812 |

| Liver + extrahepatic site | 21 (12) | 32 (19) | 0.124 |

| Extrahepatic site only | 58 (34) | 56 (33) | 0.329 |

RFA, radiofrequency ablation.

Values in table are number of patients (percentage) unless indicated otherwise.

χ2 test, unless indicated otherwise.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Complications classified as Clavien-Dindo class III or higher.

R0, no tumor cells <1 mm from the margin; R1, tumor cells <1 mm from the margin.

Subanalysis of Survival of Patients with Bilobar CLM

We also investigated the influence of RFA and R1 resection on survival in patients with bilobar CLM. Cumulative 3- and 5-year OS rates were 67% and 39%, respectively, in the patients who underwent combined resection and RFA, compared to 73% and 55%, respectively, in the patients without RFA (P=0.005) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Cumulative 1- and 3-year RFS rates were 36% and 16%, respectively, in the patients with RFA, compared to 54% and 26%, respectively, in the patients without RFA (P=0.012) (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Cumulative 3- and 5-year OS rates were 76% and 52%, respectively, in the patients with R1 resection, compared to 70% and 46%, respectively, in the patients with R0 resection (P=0.536) (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Cumulative 1- and 3-year RFS rates were 41% and 23%, respectively, in the patients with R1 resection, compared to 45% and 21%, respectively, in the patients with R0 resection (P=0.600) (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the prognostic significance of bilobar distribution on the outcomes of patients with CLM. Although patients with bilobar CLM were more likely to harbour poor prognostic features compared to unmatched patients with unilobar CLM, after controlling for these characteristics using propensity-score-matching methodology, the OS and RFS of patients who underwent resection of bilobar CLM were not significantly different from that of patients who underwent resection of unilobar CLM. These findings suggest that bilobar distribution does not independently influence the long term outcomes of patients with CLM undergoing resection and that bilobar CLM in itself is not a contraindication to liver resection.

In this study, patients with multiple CLM were more likely to have bilobar than unilobar tumor distribution (57% vs. 43%), and patients with bilobar CLM also had worse prognostic factors than those with unilobar CLM. Therefore, we used a propensity score adjustment to reduce the influence of confounding factors and to directly evaluate the influence of tumor distributions. After propensity score matching, we found that the patients with bilobar CLM were more likely to require RFA during resection and still result in R1 resection. Additionally, while the median number of lesions in the bilobar group was 4 vs. 3 in the unilobar group, both groups were clinically similar with a range of 3–15 lesions. These findings were not surprising as bilobar distribution makes it more difficult to achieve an R0 resection while leaving sufficient vascularized hepatic parenchyma.[26, 32] However, 11 patients with bilobar CLM (7%) after propensity score matching underwent 2-stage resection, which is associated with excellent outcomes in patients with advanced bilobar CLM.[14] In total, 153 patients (90%) with bilobar CLM had an R0 resection. In our matched cohort, OS and RFS in patients with bilobar CLM were not significantly different from OS and RFS in patients with unilobar CLM. This suggests that the distribution of CLM does not affect curability if the patients and surgical procedure are selected appropriately.

Previous studies have reported that combined resection with RFA is associated with worse survival.[27, 33] Indeed, in our subset analysis, we found that patients with bilobar CLM who underwent combined resection and RFA had worse outcomes compared to those who underwent resection alone. Interestingly, despite the fact that more patients in the bilobar group than the unilobar group required resection with RFA, this did not translate into differences in RFS or OS. Nevertheless, advanced surgical techniques and strategies should be considered in order to achieve margin-negative resection without RFA.[13, 14]

The influence of margin status on the survival outcomes of patients with CLM remains controversial. While some studies have suggested that an R1 resection is associated with worse survival,[22, 34] others have shown similar outcomes in patients with R1 resections, especially in those who demonstrate a good radiographic and pathologic response to preoperative chemotherapy.[35] In our subset analysis of patients with bilobar CLM undergoing resection, we found that R1 status was not associated with worse RFS or OS, presumably due to high rates of preoperative chemotherapy and careful patient selection. Not surprisingly therefore, despite patients with bilobar CLM having a higher rate of R1 resections compared to matched patients with unilobar CLM, there were no differences in OS or RFS in these matched cohorts Finally, R0 margin status has been reported to be most strongly associated with survival in patients with wild-type KRAS.[36] Unfortunately, a significant percentage of patients with bilobar CLM in our study (44%) had unknown RAS status. Therefore the relationship among RAS mutation, margin status and tumor distribution likely remains complex and future studies will be needed to further distinguish the impact of surgical margin status on OS after surgical resection of bilobar CLM from the impact of RAS status.

The strengths of this study are its relatively large sample size and detailed characterization of patient information which allows for consideration of various potential confounders through the use of comprehensive propensity score matching. Most previous reports were mainly based on the multivariate analyses of unadjusted populations,[15–19] and there was only one study looked at the clinical impact of CLM distribution using propensity score adjustment.[20] The present analysis successfully validated the outcomes of these studies using a larger population and statistically reasonable method, and accordingly, the current outcomes may strengthen the level of evidence regarding the clinical impact of CLM distribution. Although propensity score matching is an attempt to retrospectively account for pre-treatment decision factors in a statistical model, it must be acknowledged that no model can fully account for nuances of multidisciplinary treatment decision-making upfront.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged, namely its retrospective, single-institution design. As such, there is an inherent risk of selection bias based on our institutional referral pattern, patient population, and tumor board recommendations. Furthermore, a significant proportion of patients had unknown RAS status. On the other hand, the rest of the patient information was complete with little missing data. Finally, this study only includes patients who underwent resection. The selection of patients to undergo surgery may have differed among patients with unilobar versus bilobar CLM (e.g. progression during chemotherapy, unable to undergo second stage hepatectomy, etc.) leading unmeasured differences in the two groups. Despite these limitations, this analysis offers a robust comparison of unilobar versus bilobar CLM in a way that tries to remove the inherent disadvantage at which patients with bilobar CLM present.

In conclusion, our propensity-score-matched analysis indicates that the OS and RFS of patients who underwent resection of bilobar CLM were not significantly different from those of patients with unilobar CLM. Tumor distribution is therefore not an independent risk factors for worse outcomes and a multidisciplinary strategy with curative intent for liver resection is justified in well selected patients with bilobar CLM.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Cumulative overall survival (A) and recurrence-free survival (B) in patients with multiple bilobar colorectal liver metastases undergoing resection according to use of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or not after propensity score matching.

Supplementary Figure 2. Cumulative overall survival (A) and recurrence-free survival (B) in patients with multiple bilobar colorectal liver metastases undergoing resection according to resection type (R1 or R0) after propensity score matching.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize Ms. Ruth Haynes for administrative support in the preparation of this manuscript and thank Stephanie Deming, employees of the Department of Scientific Publications at MD Anderson Cancer Center, for copyediting the manuscript. This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Support Grant, CA01667.

Abbreviations

- CLM

colorectal liver metastases

- RFA

radiofrequency ablation

- RAS

rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- OS

overall survival

- RFS

recurrence-free survival

- CI

confidence intervals

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest associated with this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Steele G, Jr, Ravikumar TS. Resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Biologic perspective Ann Surg. 1989;210:127–38. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198908000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kopetz S, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam R, et al. The oncosurgery approach to managing liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Oncologist. 2012;17:1225–39. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adam R, et al. Managing synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:729–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chun YS, et al. Systemic chemotherapy and two-stage hepatectomy for extensive bilateral colorectal liver metastases: perioperative safety and survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1498–504. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0272-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gayowski TJ, et al. Experience in hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of clinical and pathologic risk factors. Surgery. 1994;116:703–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanebo HJ, et al. Patient selection for hepatic resection of colorectal metastases. Arch Surg. 1996;131:322–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430150100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fong Y, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–18. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakamoto Y, et al. Is surgical resection justified for stage IV colorectal cancer patients having bilobar hepatic metastases?--an analysis of survival of 77 patients undergoing hepatectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:784–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.21721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sorbye H, et al. Predictive factors for the benefit of perioperative FOLFOX for resectable liver metastasis in colorectal cancer patients (EORTC Intergroup Trial 40983) Ann Surg. 2012;255:534–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182456aa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin Q, et al. Determinants of long-term outcome in patients undergoing simultaneous resection of synchronous colorectal liver metastases. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shindoh J, et al. Portal vein embolization improves rate of resection of extensive colorectal liver metastases without worsening survival. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1777–83. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shindoh J, et al. Safety and efficacy of portal vein embolization before planned major or extended hepatectomy: an institutional experience of 358 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2369-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouquet A, et al. High survival rate after two-stage resection of advanced colorectal liver metastases: response-based selection and complete resection define outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1083–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cady B, et al. Surgical margin in hepatic resection for colorectal metastasis: a critical and improvable determinant of outcome. Ann Surg. 1998;227:566–71. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elias D, et al. Results of 136 curative hepatectomies with a safety margin of less than 10 mm for colorectal metastases. J Surg Oncol. 1998;69:88–93. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9098(199810)69:2<88::aid-jso8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minagawa M, et al. Extension of the frontiers of surgical indications in the treatment of liver metastases from colorectal cancer: long-term results. Ann Surg. 2000;231:487–99. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200004000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Homayounfar K, et al. Bilobar spreading of colorectal liver metastases does not significantly affect survival after R0 resection in the era of interdisciplinary multimodal treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:1359–67. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1455-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vigano L, et al. Liver resection in patients with eight or more colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2015;102:92–101. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukami Y, et al. Bilobar versus unilobar multiple colorectal liver metastases: a propensity score analysis of surgical outcomes and recurrence patterns. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:153–60. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nordlinger B, et al. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Francaise de Chirurgie Cancer. 1996;77:1254–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rees M, et al. Evaluation of long-term survival after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multifactorial model of 929 patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:125–35. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815aa2c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith MD, McCall JL. Systematic review of tumour number and outcome after radical treatment of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1101–13. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beppu T, et al. A nomogram predicting disease-free survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases treated with hepatic resection: multicenter data collection as a Project Study for Hepatic Surgery of the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:72–84. doi: 10.1007/s00534-011-0460-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kishi Y, et al. Three hundred and one consecutive extended right hepatectomies: evaluation of outcome based on systematic liver volumetry. Ann Surg. 2009;250:540–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b674df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawlik TM, et al. Combined resection and radiofrequency ablation for advanced hepatic malignancies: results in 172 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:1059–69. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2003.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdalla EK, et al. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818–25. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128305.90650.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dindo D, et al. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mullen JT, et al. Hepatic insufficiency and mortality in 1,059 noncirrhotic patients undergoing major hepatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:854–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.12.032. discussion 62–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Austin PC. Some methods of propensity-score matching had superior performance to others: results of an empirical investigation and Monte Carlo simulations. Biom J. 2009;51:171–84. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200810488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West SG, et al. Propensity scores as a basis for equating groups: basic principles and application in clinical treatment outcome research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:906–19. doi: 10.1037/a0036387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kishi Y, et al. Extended preoperative chemotherapy does not improve pathologic response and increases postoperative liver insufficiency after hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2870–6. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gleisner AL, et al. Colorectal liver metastases: recurrence and survival following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection-radiofrequency ablation. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1204–12. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.12.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sadot E, et al. Resection margin and survival in 2368 patients undergoing hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: surgical technique or biologic surrogate? Ann Surg. 2015;262:476–85. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andreou A, et al. Margin status remains an important determinant of survival after surgical resection of colorectal liver metastases in the era of modern chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1079–88. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318283a4d1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Margonis GA, et al. Tumor Biology Rather Than Surgical Technique Dictates Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1821–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Cumulative overall survival (A) and recurrence-free survival (B) in patients with multiple bilobar colorectal liver metastases undergoing resection according to use of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or not after propensity score matching.

Supplementary Figure 2. Cumulative overall survival (A) and recurrence-free survival (B) in patients with multiple bilobar colorectal liver metastases undergoing resection according to resection type (R1 or R0) after propensity score matching.