HIV testing is crucial to HIV prevention. Routine testing allows those infected with HIV to discover their status earlier. Early awareness of HIV status could prompt individuals to begin antiretroviral treatment to decrease their viral load, which ultimately can prevent transmission to others in the community by over 90% (Cohen et al., 2011). Additionally, HIV-positive patients who know their status engage in fewer risky behaviors, further decreasing spread of HIV to others in the community (Marks, Crepaz, Senterfitt, & Janssen, 2005). Although patients want and expect HIV testing (McAfee et al., 2013), physicians unfortunately fail to recognize this desire and do not regularly offer testing (Arya et al., 2014). Physicians believe that patients will be uncomfortable discussing HIV testing, will be offended if offered the test, and will refuse the test (Arya et al., 2014; Korthuis et al., 2011). Prompting patients to request HIV testing may mitigiate this disconnect between patient desires and expectations, and physician beliefs and behaviors, thereby increasing testing rates and improving the prevention of HIV.

Text messaging can effectively engage patients in their health and enhance patient-physician communication (Cole-Lewis & Kershaw, 2010). Text message prompts, therefore, could educate patients about HIV and cue them to initiate an HIV testing conversation with their physician, improving both patient-physician communication and HIV testing rates. To our knowledge, text messaging as an intervention to increase HIV testing by promoting patient-physician communication about HIV and HIV testing has not been substantially investigated. The objectives of our study were to determine if patients would be comfortable requesting HIV testing and if they could be encouraged to do so by a text message prompt.

METHODS

The study was conducted between June, 2014 and February, 2015 in a publicly funded community health center (CHC) serving predominantly low-income, racial, and ethnic minority patients in northwest Houston. The CHC’s primary care clinic, staffed by family medicine physicians, provides a continuum of care for more than 40,000 visits in a fiscal year. These family medicine physicians see an average of 144 patients per day.

We recruited participants from a convenience sample of patients in the central waiting room of the CHC’s primary care clinic. Posters advertising the study and the gift card incentive were placed in the waiting room to increase participant recruitment. Participants were eligible if they were 18 years or older and fluent in English. Participants provided verbal consent after the researcher explained the study and answered any questions that they had. Participants completed a self-administered survey in the waiting room. The three main survey questions of interest were 1) “Have you ever talked to your doctor at this clinic about being tested for HIV?” 2) “How comfortable would you be asking your doctor for an HIV test?” and 3) “Would you be comfortable receiving a text message about getting tested for HIV?” We also asked participants if they had text messaging on their mobile phones in addition to standard demographic questions. We offered a $10 gift card to participants upon survey completion. The Institutional Review Board of Baylor College of Medicine approved this study.

Two research assistants independently entered survey answers into a Microsoft Access database (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA) and imported the data into Stata 13 (StataCorp; College Station, TX). The research assistants catalogued discrepancies in data entry and the research team mediated these discrepancies. Standard descriptive statistics were used for data analysis. When analyzing participants’ answers, we combined the responses “comfortable” and “very comfortable” into “comfortable” in order to characterize participants’ comfort level. Similarly, we combined “not at all comfortable” and “somewhat comfortable” into “not comfortable.”

RESULTS

Of the 285 participants who completed the survey, we report data from the 265 who answered all three questions. Of these, 263 provided their ages. The ages ranged from 18 to 82, with a median of 54. Of the participants who provided their gender (n = 264), more than two-thirds were female (68%). The majority of participants were non-Hispanic African American (40%) or Hispanic (23%). About half of participants (51%) had attained a high school education or less. Most participants (74%) had a yearly income of less than $20,000.

As shown in Table 1, more than half of all participants had never talked to their physicians about HIV testing (n = 146, 55%); however, most stated that they would be comfortable asking their physicians for the test (n = 146, 55%). Furthermore, of participants who had text messaging capacity (n = 225), more than half would be comfortable receiving an HIV-testing text-message prompt (n = 130, 58%).

Table 1.

Participant Experience and Comfort with HIV Testing Discussions (N = 265)

| Survey Question | Answer Choices | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Have you ever talked to your doctor at this clinic about being tested for HIV?” | Yes | 100 | 38 |

| No | 146 | 55 | |

| I don’t remember | 19 | 7 | |

| “How comfortable would you be asking your doctor for an HIV test?” | Not at all comfortable | 28 | 11 |

| Somewhat comfortable | 28 | 11 | |

| Comfortable | 96 | 36 | |

| Very comfortable | 113 | 43 | |

| “Would you be comfortable receiving a text message about getting tested for HIV?” | Yes | 130 | 49 |

| No | 95 | 36 | |

| I don’t have text messaging | 40 | 15 |

Of those who had never talked to their physicians about HIV testing (n = 146), nearly three-quarters (n = 108, 74%) indicated they would be comfortable asking their physicians for the HIV test. Of these 108 participants, the majority had text messaging (n = 88, 81%). Fifty-seven of these participants (65%) would be comfortable receiving an HIV-testing text-message prompt.

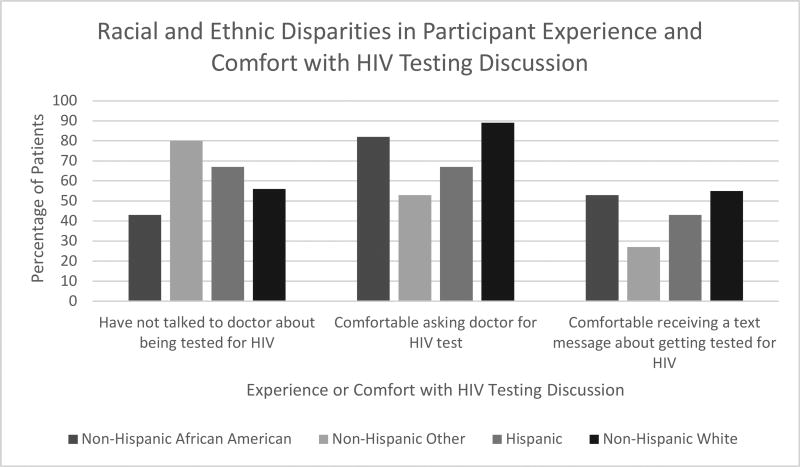

Because HIV has a disproportionate impact on minority communities, we analyzed patient experience and comfort with HIV testing discussions by race and ethnicity. More than half of all racial and ethnic minority participants had not talked to their physicians about the HIV test (n = 99, 54%). Similarly, 56% (I = 45) of non-Hispanic White participants had not talked to their physicians about the HIV test. Three-quarters of minority participants (n = 136) were comfortable asking their physicians for the HIV test. In comparison, almost all non-Hispanic White participants were comfortable asking for the HIV test (n = 71, 89%). About one-half of minority participants (n = 86, 47%) and one-half of non-Hispanic White participants (n = 44, 55%) were comfortable receiving an HIV-testing text-message prompt (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Participant Experience and Comfort with HIV Testing Discussion.1

1 Figure includes a total of 265 participants who answered the three main survey questions of interest and provided demographic information.

DISCUSSION

HIV testing is a critical step in HIV prevention (Marks et al., 2005). Despite this benefit of HIV testing, we found that a majority of participants had not previously talked with their physicians about HIV testing, although most participants indicated they would be comfortable initiating this discussion. We also found that a majority of participants would be comfortable receiving a text message with HIV testing content. Moreover, among those who had never had an HIV testing discussion with their physicians, more than one-third would be comfortable receiving a text message about HIV testing.

Using text messages to activate patients to initiate HIV testing discussions may help overcome the disconnect in patient-physician HIV testing communication and improve HIV testing rates. In order for text messages to activate patients, the content of the message should provide information about the importance of HIV testing and provide a direct cue to talk to their physicians. A text message sent at an opportune moment – such as immediately before a patient enters the examination room – could be a timely cue to activate patients to bring up HIV testing with her/his physician. An example of the text message could be, “All adults in our clinic should get tested for HIV. Ask Dr. Jones for the test at your appointment today.”

A text message campaign may be especially effective for minority patients, a population that is at high risk for HIV and more likely to be tested for HIV at a later stage of the disease; i.e., they are more likely to be diagnosed with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) within one year of their HIV diagnosis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Ninety-four percent of African Americans and 92% of Hispanics own mobile phones (Anderson, 2015), and more than 85% of them use text messaging (Duggan, 2013). Furthermore, the typical mobile phone owner opens 99% of text messages (Lane, 2010), supporting the potential effectiveness of text messaging for communicating important health-related information. We found that nearly half of minority participants would be comfortable receiving an HIV-testing text-message prompt, suggesting that a text message campaign could help promote HIV education, increase HIV testing rates, and reduce HIV transmission in these populations.

Preliminary evidence suggests that patients will follow through with requesting the HIV test when prompted to do so. A text messaging intervention in South Africa encouraging patients to seek HIV testing found that over half of participants who were texted subsequently obtained testing (de Tolly, Skinner, Nembaware, & Benjamin, 2012). Notably, this study did not focus on improving patient-physician communication regarding HIV testing, a known barrier to HIV testing in U.S. healthcare settings (Arya et al., 2014; Korthuis et al., 2011). To our knowledge, no study has explored the potential for a mobile health campaign to improve patient-physician communication about HIV testing and subsequent HIV testing rates.

For the few participants who are uncomfortable asking for the HIV test, text message prompts to discuss testing may not be as effective. While nearly all White patients (89%) were comfortable asking for the test, comparatively fewer minority patients (75%) were comfortable doing so. Minority patients’ discomfort may stem from disparities in patient-physician communication. Compared to Whites, minorities have less effective and less frequent communication with their physicians (Johnson, Roter, Powe, & Cooper, 2004) and, therefore, may be more reluctant to ask for the HIV test. Barriers, such as stigma and embarrassment, also may prevent patients from asking for testing. Efforts to further understand and reduce patient discomfort are warranted, especially as minorities tend to have delayed HIV diagnoses (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015).

While sending text messages to patients may be an innovative tool for promoting HIV prevention, patient-focused interventions may be bolstered by campaigns aimed at providers (Arya, Phillips, Street, & Giordano, 2016). Delivering tailored interventions to providers to improve their communications with racially and socioeconomically diverse populations can increase these providers’ confidence in managing patient interactions (Sullivan et al., 2011). Such interventions may encourage providers, who report being unsure of how to initiate conversations about HIV testing (Arya et al., 2014), to offer their patients the test. Teaching providers communication strategies for discussing the benefits of HIV testing with their patients may result in patients being more receptive to HIV testing. Thus, focusing on both patients and providers may improve their communication and result in more informed and engaged patients (Rao, Anderson, Inui, & Frankel, 2007).

There were limitations to our study. Our population was small and consisted of predominantly racial and ethnic minority patients from one clinic. As such, our findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Notably, our findings are salient for exploring HIV testing interventions targeting racial and ethnic minorities who are at high risk for HIV and late testing (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Because our study used a convenience sample and participants opted-in to take the survey, response bias may be present. No data were collected on the number of patients approached for recruitment and, of those, the number of those who elected to participate. Our study population may have been more inclined to participate actively in their healthcare and/or answer questions pertaining to HIV, potentially explaining why we found that the majority of patients would be comfortable discussing HIV with their physicians. No chart review was performed to obtain objective data on participants’ prior HIV testing. The gift card incentive we offered may also have influenced study participation among this low-income population; however, we do not believe that this modest $10 incentive was coercive.

CONCLUSION

Our findings from a predominantly racial and ethnic minority population support the potential of a text message campaign for promoting HIV testing by improving patient-physician communication about routine HIV testing. Racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to be tested late for HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015), highlighting the need for targeted HIV testing campaigns among these populations. Furthermore, promoting HIV testing is particularly important for cities, such as Houston, that continue to be burdened by high HIV prevalence (Houston Health Department, HIV Surveillance Program, 2015). Text messages that encourage patients to request the HIV test could help accomplish the Healthy People 2020 goals of using health communication strategies and technology to improve population health and increasing both the proportion of individuals tested for HIV and the proportion of those living with HIV who know their status (“2020 Topics and Objectives,” 2017). Research is now needed to determine the optimal content for such a text message campaign and determine its efficacy for improving HIV testing discussions among patients and their physicians. Text messages for HIV testing may be a needed addition to the toolbox for HIV prevention in minority communities.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alexandra Trenary, Sajani Patel, and Ashley Phillips for their contributions to data collection. The authors would like to thank the Harris Health System and their patients for their participation in this study. This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23MH094235 (PI: Arya). This work was supported in part by the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (#CIN 13-413) of the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Monisha Arya, Baylor College of Medicine, and Health Communications Investigator, Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affair Medical Center Houston, TX, USA.

Anna Huang, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

Disha Kumar, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Vagish Hemmige, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, USA.

Richard L. Street, Jr., Department of Communication, Texas A&M University, College Station, and Professor, Baylor College of Medicine, and Chief, Health Decision-Making and Communication Program, Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affair Medical Center, Houston, Texas, USA.

Thomas P. Giordano, Baylor College of Medicine, and Chief, Clinical Epidemiology and Comparative Effectiveness Program, Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness, and Safety, Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affair Medical Center, Houston, Texas, USA.

References

- 2020 Topics and Objectives. [Retrieved May 6, 2017];2017 Feb 24; from https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives.

- Anderson M. [Retrieved May 5, 2017];Technology device ownership: 2015. 2015 Oct 29; from http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/10/29/technology-device-ownership-2015/

- Arya M, Patel S, Kumar D, Zheng M, Amspoker A, Kallen M, Giordano T. Why physicians don’t ask: Interpersonal and intrapersonal barriers to HIV testing-- making a case for a patient-initiated campaign. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2014;5:1–7. doi: 10.1177/2325957414557268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya M, Phillips AL, Street RL, Giordano TP. Physician preferences for physician-targeted HIV testing campaigns. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC) 2016;15(6):470–476. doi: 10.1177/2325957416636475. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325957416636475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas. 2015;2014(26) Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-us.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Fleming TR. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Text messaging as a tool for behavior change in disease prevention and management. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2010;32(1):56–69. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxq004. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxq004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Tolly K, Skinner D, Nembaware V, Benjamin P. Investigation into the use of short message services to expand uptake of human immunodeficiency virus testing, and whether content and dosage have impact. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health: The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association. 2012;18(1):18–23. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2011.0058. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2011.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M. Additional demographic analysis. Pew Research. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/09/19/additional-demographic-analysis/

- Houston Health Department, HIV Surveillance Program. HIV infection in Houston: An epidemiologic profile 2010–2014. Houston, TX: 2015. Retrieved from http://www.houstontx.gov/health/HIV-STD/HI_%20Epi_Profile_20160506_this.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis PT, Berkenblit GV, Sullivan LE, Cofrancesco J, Cook RL, Bass M, Sosman JM. General internists’ beliefs, behaviors, and perceived barriers to routine hiv screening in primary care. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2011;23(3_supplement):70–83. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.70. https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2011.23.3_supp.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane N. Conversational advertising. SinglePoint. 2010 Retrieved from http://mobilesquared.co.uk/media/27820/Conversational-Advertising_SinglePoint_2010.pdf.

- Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999) 2005;39(4):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAfee L, Tung C, Espinosa-Silva Y, Rahman M, Fatima K, Clark R, Pearce D. A survey of a small sample of emergency department and admitted patients asking whether they expect to be tested for HIV routinely. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2013;12(4):247–252. doi: 10.1177/2325957413488197. https://doi.org/10.1177/2325957413488197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, Frankel RM. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Medical Care. 2007;45(4):340–349. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254516.04961.d5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000254516.04961.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MF, Ferguson W, Haley H-L, Philbin M, Kedian T, Sullivan K, Quirk M. Expert communication training for providers in community health centers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(4):1358–1368. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0129. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2011.0129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]