Abstract

Objective

The endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous technique (EUS-RV) is a salvage method for failed selective biliary cannulation. Three puncture routes have been reported, with many comparisons between the intra-hepatic and extra-hepatic biliary ducts. We used the trans-esophagus (TE) and trans-jejunum (TJ) routes. In the present study, the utility of EUS-RV for biliary access was evaluated, focusing on the approach routes.

Methods and Patients

In 39 patients, 42 puncture routes were evaluated in detail. EUS-RV was performed between January 2010 and December 2014. The patients were prospectively enrolled, and their clinical data were retrospectively collected.

Results

The patients' median age was 71 (range 29-84) years. The indications for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) were malignant biliary obstruction in 24 patients and benign biliary disease in 15. The technical success rate was 78.6% (33/42) and was similar among approach routes (p=0.377). The overall complication rate was 16.7% (7/42) and was similar among approach routes (p=0.489). However, mediastinal emphysema occurred in 2 TE route EUS-RV patients. No EUS-RV-related deaths occurred.

Conclusion

EUS-RV proved reliable after failed ERCP. The selection of the appropriate route based on the patient's condition is crucial.

Keywords: EUS-RV, EUS, ERCP

Introduction

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the standard technique for relief of biliary diseases. Therapeutic ERCP requires deep cannulation, and although the success rate of deep cannulation is high (97-98.5%) with advanced techniques such as wire-guided cannulation, precutting procedures, and guide wire placement in the pancreatic duct, it is still not perfect (1-3). Therefore, some patients require percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) or surgical drainage. However, PTBD and surgical drainage are associated with considerable morbidity rates, patient discomfort, the need for repeated intervention, and occasional mortality (4-6).

The development of a linear array echoendoscope has enabled various endoscopic ultrasound-related diagnostic and therapeutic techniques to be performed, such as fine-needle aspiration (FNA) (7), pancreatic pseudocyst drainage (8), and celiac plexus neurolysis (9). In 2001, EUS-guided biliary drainage was reported for the first time (10). EUS-guided rendezvous technique (EUS-RV) were first reported in 2004 by Mallery (11). Recently, EUS-RV has been reported as an effective salvage technique after failed ERCP. In the literature, three puncture routes have been reported: trans-gastric (TG), trans-duodenal short position (TDS), and trans-duodenal long position (TDL). We use the trans-esophagus (TE) and trans-jejunum (TJ) routes at our facility.

However, no report has evaluated puncture routes such as the TE or TJ route in detail. Therefore, we evaluated the utility of EUS-RV for biliary access with particular focus on the approach route.

Materials and Methods

Patients

A total of 1883 ERCPs were performed at our institution between January 2010 and December 2014, and 39 (42 procedures) of these patients underwent EUS-RV for biliary access after failed ERCP. Failed ERCP was defined as biliary cannulation that failed despite the use of advanced cannulation techniques by a skilled endoscopist, inaccessible papilla, or choledochojejunostomy and failure to pass the stricture. EUS-RV was performed on the same day as failed ERCP or a few days later, depending on the patient's condition. All patients provided their informed consent for the procedures, and the local institutional review board approved the study. The patients were prospectively enrolled, and the clinical data were retrospectively collected for these 42 cases. An intention-to-treat analysis was used to evaluate the technical success rate.

Techniques

Antibiotics were permitted in all cases before and after the intervention. EUS was performed using a linear array echoendoscope (GF-UGT240, GU-UGT260; Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) connected to an ultrasound device (EU-ME2; Olympus Medical Systems or SSD-α10; Aloka, Tokyo, Japan). Following the evaluation of the biliary system, either an extrahepatic biliary duct (EHBD) or an intrahepatic biliary duct (IHBD) was punctured with a 19- or 22-gauge needle under EUS guidance (Fig. 1). A 19-gauge needle is better, as it can accommodate a 0.025-inch guide wire. After puncturing the bile duct, contrast medium was injected into the bile duct to confirm the anatomy. A 0.025-inch angle tip guide wire (VisiGlide2; Olympus Medical Systems) was then advanced through the needle and manipulated antegrade into the small bowel via the native ampulla or surgical anastomosis. The guide wire tends to stick because the sharp edge of the needle penetrates the covering membrane and sometimes strips it off. To avoid this, the guide wire should not be pulled back, and a thin guide wire should be used. The needle and echoendoscope were then exchanged for a duodenoscope while keeping the guide wire in place. The catheter was then inserted through the papilla alongside the antegradely placed guide wire. If this attempt failed, the guide wire was grasped with a loop cutter (Olympus Medical Systems) (Fig. 2) and pulled out through the working channel of the duodenoscope, followed by over-the-wire biliary cannulation. After successful bile duct cannulation, different types of biliary intervention, such as biliary sphincterotomy or biliary stenting, were performed, depending on the patient's condition.

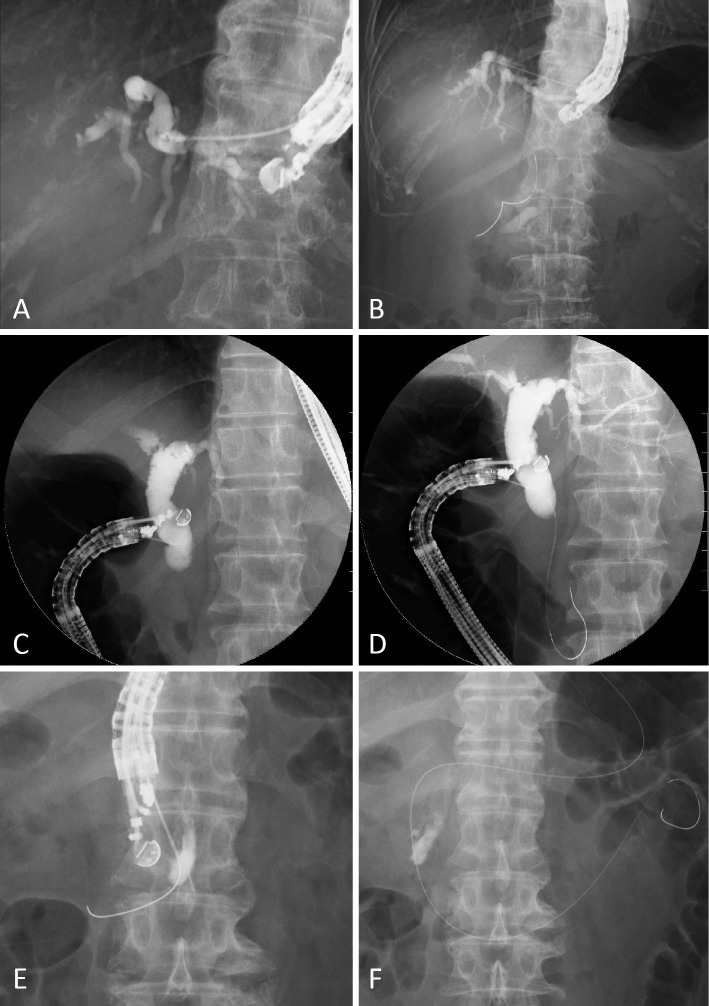

Figure 1.

EUS-Rendezvous technique. A, B: Trans-gastric route. The left intra-hepatic bile duct (B3) was punctured using the 19-G needle, and cholangiography was obtained (A). The guide wire was passed through the biliary stricture and papilla (B). The trans-esophagus and trans-jejunum routes are similar. C, D: Trans-duodenal long position. The extra-hepatic bile duct was punctured from the duodenum, and cholangiography was obtained (C). The guide wire passed through the papilla (D). E, F: Trans-duodenal short position. The extra-hepatic bile duct was punctured from the second portion of the duodenum, and the guide wire was passed through the papilla (E). The scope was exchanged for a duodenoscope while keeping the guide wire in place (F).

Figure 2.

Loop cutter (Olympus Medical Systems).

Data analyses

The main outcome measure of the study was technical success. The secondary outcome was complications. The severity of complications following endoscopic procedures was assessed according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines (12).

Results

Between January 2010 and December 2014, 1883 procedures included ERCP, and 39 patients (42 procedures) underwent EUS-RV after failed ERCP. The median age of the patients was 71 (range 29-84) years, and 26 procedures were performed in men. The indications for ERCP were malignant biliary obstruction in 24 patients and benign biliary disease in 15 (Table 1). The reasons for EUS-RV were surgically altered anatomy in 33.3% (14/39), failed passage through the stricture in 17.9% (7/39), failed cannulation in 17.9% (7/39), cancer infiltration in 12.8% (5/39), peri-ampullary diverticulum in 7.7% (3/39), and other technical reasons in 7.7% (3/39) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| N=39 | |

|---|---|

| Age, median[range] | 71[29-84] |

| Males : Females | 26:13 |

| Indications for ERCP Malignant biliary obstruction, n | 24 |

| Pancreatic cancer | 7 |

| Gastric cancer | 5 |

| Bile duct cancer | 3 |

| Cholangiocellular carcinoma | 3 |

| Gallbladder cancer | 2 |

| Colorectal cancer | 2 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 |

| Cancer of unknown primary | 1 |

| Benign biliary disease, n | 15 |

| Stone | 9 |

| Benign stricture | 4 |

| Stricture of choledochojejunostomy | 2 |

Table 2.

Reasons for EUS-RV.

| n(%) | |

|---|---|

| Surgically altered anatomy | 14(33.3) |

| TG+R-Y | 4 |

| DG+Billroth I | 3 |

| DG+Billroth II | 2 |

| PD+child | 3 |

| Others | 2 |

| Failed passing through the stricture | 7(17.9) |

| Failed cannulation | 7(17.9) |

| Cancer infiltration | 5(12.8) |

| Peri-ampullary diverticulum | 3(7.7) |

| Other technical reasons | 3(7.7) |

TG+R-Y: total gastrectomy+Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, DG: distal gastrectomy, PD: pancreatoduodenectomy

A total of 35 rendezvous procedures were performed in the same session as the initial ERCP attempt, and 7 were performed at a subsequent session. The success rate of bile duct puncture and cholangiography was 97.6% (41/42). In only one case, there was no bile duct dilation, and therefore puncture could not be performed. Regarding the choice of approach route, the TG route was most commonly selected in both the non-altered and altered anatomy groups. The TE route was selected as the next-most common route in both anatomy groups. The TJ route was performed only in the altered anatomy group. EUS-RV was successful in 19 of 26 non-altered anatomy patients (73.1%) and 14 of 16 altered anatomy patients (87.5%). The technical success rates were similar between the two group (p=0.268). The overall success rate of EUS-RV was 78.6% (33/42) (Table 3). In comparing the technical success rate among the approach routes [TE 90.9% (10/11), TG 75.0% (12/16), TDL 57.1% (4/7), TDS 75.0% (3/4), TJ100% (4/4)], no significant differences were noted (p=0.377) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Outcomes of EUS-RV.

| Non-altered anatomy N=26 | Altered anatomy N=16 | Total | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter of bile duct, median[range], mm | 5[2-16] | 5[3-8] | ||

| Procedure time, median[range], min | 60[20-186] | 63[20-122] | ||

| Approach route, %(n/N) | ||||

| Esophagus (TE) | 30.8(8/26) | 18.8(3/16) | 26.2(11/42) | |

| Gastric (TG) | 34.6(9/26) | 43.8(7/16) | 38.1(16/42) | |

| Duodenal bulb (TDL) | 26.9(7/26) | 0(0/16) | 16.7(7/42) | |

| Duodenum, second portion (TDS) | 7.7(2/26) | 12.5(2/16) | 9.5(4/42) | |

| Jejunum (TJ) | 0(0/26) | 25.0(4/16) | 9.5(4/42) | |

| The success rate of bile duct puncture and cholangiography, %(n/N) | 96.2(25/26) | 100.0(16/16) | 97.6(41/42) | ns |

| Technical success rate, %(n/N) | 73.1(19/26) | 87.5(14/16) | 78.6(33/42) | ns |

| Complication rate, %(n/N) | 11.5(3/26) | 25.0(4/16) | 16.7(7/42) | ns |

TE: transesophageal route, TG: transgastric route, TDL: transduodenal route long position, TDS: transduodenal route short position, TJ: transjejunum route, ns: not significant, N/A: not appricable

Table 4.

Comparison of Clinical Backgrounds and Success Rate of Approach Route.

| Success rate, % (n/N) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE | TG | TDL | TDS | TJ | ||||||||

| N=11 | N=16 | N=7 | N=4 | N=4 | p value† | |||||||

| Clinical backgrounds | ||||||||||||

| Malignant/Benign | 100.0 | 66.7 | 72.7 | 80.0 | 60.0 | 50.0 | 66.7 | 100.0 | - | 100.0 | ||

| (8/8) | (2/3) | (8/11) | (4/5) | (3/5) | (1/2) | (2/3) | (1/1) | (0/0) | (4/4) | |||

| Non altered/Altered | 87.5 | 100.0 | 66.6 | 100.0 | 57.1 | - | 100.0 | 50.0 | - | 100.0 | ||

| (7/8) | (3/3) | (6/9) | (6/6) | (4/7) | (0/0) | (2/2) | (1/2) | (0/0) | (4/4) | |||

| Ampulla/Anastomosis | 90.0 | 100.0 | 69.2 | 100.0 | 57.1 | - | 75.5 | - | 100.0 | - | ||

| (9/10) | (1/1) | (9/13) | (3/3) | (4/7) | (0/0) | (3/4) | (0/0) | (4/4) | (0/0) | |||

| Obstruction side EHBD/ IHBD | 100.0 | 75.0 | 70.0 | 83.3 | 100.0 | 40.0 | 66.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 | - | ||

| (7/7) | (3/4) | (7/10) | (5/6) | (2/2) | (2/5) | (2/3) | (1/1) | (4/4) | (0/0) | |||

| Over all technical success rate | 90.9(10/11) | 75.0(12/16) | 57.1(4/7) | 75.0(3/4) | 100.0(4/4) | 0.377 | ||||||

†Chi-square test.

TE: transesophageal route, TG: transgastric route, TDL: transduodenal route long position, TDS: transduodenal route short position, TJ: transjejunum route

There were nine patients in whom EUS-RV failed, with reasons described as follows: kinking of the guide wire (n=4), failed passage through the stricture (n=3), no bile duct dilation (n=1), and others (n=1). In this study, there were no cases in which access to the papilla could not be achieved or the guide wire was lost.

Three patients in whom EUS-RV failed due to kinking of the guide wire were salvaged with immediate repeat EUS-RV, the success of which was attributed to changing the puncture route. In all cases, the first EUS-RV involved puncture of the extrahepatic bile duct from the stomach or duodenum, and the second EUS-RV involved puncture of the left intrahepatic bile duct from the stomach or esophagus. Changing the puncture route prevented guide wire kinking and allowed easy manipulation. Another patient underwent EUS-biliary drainage. The remaining five patients underwent PTBD (n=3) or ERCP (n=2) within 3 days (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of Failed EUS-RV.

| Patient No | Age | Sex | Diagnosis | Reason for failed EUS-RV | Salvage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 79 | F | Gallbladder cancer | Kinking of a guide wire | Repeat EUS-RV |

| 2 | 84 | F | Gallbladder cancer | Kinking of a guide wire | Repeat EUS-RV |

| 3 | 78 | M | Pancreatic cancer | Kinking of a guide wire | Repeat EUS-RV |

| 4 | 64 | M | Colon cancer | Kinking of a guide wire | Repeat ERCP |

| 5 | 47 | M | Stricture of choledochojejunostomy | Failed passing through the stricture | PTBD |

| 6 | 74 | M | Cholangiocellular carcinoma | Failed passing through the stricture | PTBD |

| 7 | 56 | M | Colon cancer | Failed passing through the stricture | EUS-HDS |

| 8 | 29 | M | Cancer of unknown primary | No bile duct dilation | PTBD |

| 9 | 74 | F | Colon cancer | Others | Repeat ERCP |

EUS-RV: endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous technique, PTBD: percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, EUS-HDS: endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepatico jejunostomy

Complications

Complications were observed in 7 patients (16.7%, 7/42) in this study. The complication rate was 11.5% in non-altered anatomy patients (3/26) and 25.0% in altered anatomy patients (4/16), rates which were between the two groups (p=0.255) (Table 3). In comparing the complication rate among approach routes [TE 18.1% (2/11), TG 6.2% (1/16), TDL 14.3% (1/7), TDS 50.0% (2/4), TJ 25.0% (1/4)], no significant differences were noted (p=0.498) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Comparison of Complications of Approach Route.

| Approach route | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TE N=11 | TG N=16 | TDL N=7 | TDS N=4 | TJ N=4 | p value† | |

| Early complications, n (grade*) | Mediastinal emphysema, 2(moderate) | Retroperitoneal perforation, 1(moderate) | Cholangitis, 1(moderate) | Peritonitis, 1(moderate) Pancreatitis, 1(mild) | Peritonitis, 1(moderate) | |

| Late complications, n (grade*) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Over all complication rate, %(n/N) | 18.1(2/11) | 6.2(1/16) | 14.3(1/7) | 50.0(2/4) | 25.0(1/4) | 0.489 |

TE: transesophageal route, TG: transgastric route, TDL: transduodenal route long position, TDS: transduodenal route short position, TJ: transjejunum route

Early adverse events : within 14 days, Late adverse events : after 14 days.

*Severity grading system in ref (12).

†Chi-square test.

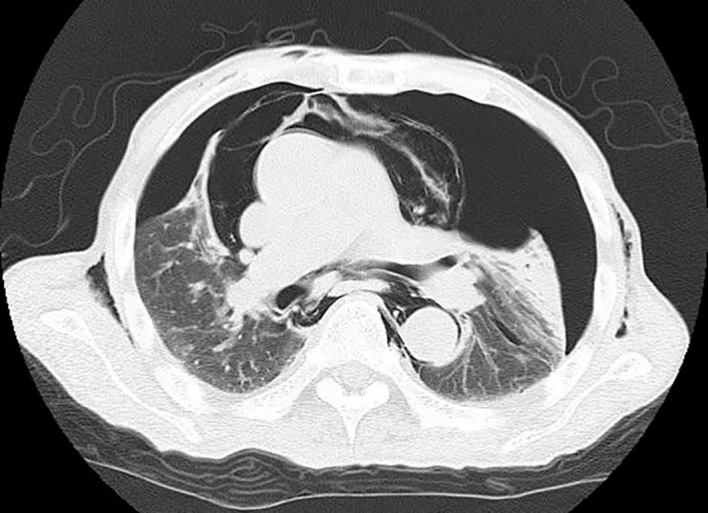

Moderate mediastinal emphysema occurred in two patients who underwent TE route EUS-RV. In both cases, the 19-gauge needle was changed to an ERCP tapered catheter from the puncture route for guide wire manipulation. Mediastinal emphysema and pneumothorax were observed in one patient with anastomotic biliary stricture who underwent EUS-RV via the TE route (Fig. 3). Chest drainage was performed, and antibiotics were given for 5 days. On day 2, the pneumothorax improved, and the patient was discharged home on day 6. Another patient was treated conservatively. Moderate mediastinal emphysema occurred in only two cases through a device that was bigger than a 19-gauge needle. There were no complications in any other EUS-RV cases approached via the TE route. One case of moderate cholangitis occurred, requiring PTBD the next day. One case of mild pancreatitis, two cases of moderate peritonitis, and one case of retroperitoneal perforation occurred, and all cases were treated conservatively. There were no late complications and no EUS-RV-related deaths (Table 6).

Figure 3.

Computed tomography revealed mediastinal emphysema and pneumothorax.

Discussion

Since the initial report on the use of EUS-RV after failed ERCP in 2004, several studies (13-22) have reported EUS-RV as an effective salvage technique for achieving biliary cannulation after failed ERCP. The EUS-RV techniques comprise three methods that are based on the approach route: TG, from the second portion of the duodenum in a short endoscopic position (TDS), and from the bulb of the duodenum in a long endoscopic position (TDL). No report has evaluated puncture routes such as the TE or TJ route in detail. In the current study, each EUS-RV technique was successful in all patients without significant morbidities. The previously published articles involving EUS-RV for biliary access after failed ERCP are reviewed in Table 7 (13-20). There were no significant differences in the rates of rendezvous success or complications among the approach routes.

Table 7.

EUS-RV for Biliary Access in the Reported Cases.

| Reference | Years | Number of cases | Puncture site | Puncture success(%) | Rendezvous success(%) | Total rendezvous success(%) | Complication (n) | Complication rate(%) | Total complication rate(%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 | 2008 | 12 | TDL | 12 | 100 | TDL | 58 | 58 | Pneumoperitoneum 1, Respiratory failure 1 | TDL | 13 | 13 |

| 14 | 2009 | 49 | TG | 35 | 100 | TG | 69 | 84 | Bleeding 1, Pneumoperitoneum 1 | TG | 14 | 16 |

| TDS | 14 | TDS | 57 | Pneumonia 1, Peritonitis 1, Abdominal pain 1, Pneumoperitoneum 1 | TDS | 21 | ||||||

| 15 | 2010 | 15 | TDS | 15 | 100 | TDS | 80 | 80 | Pancreatitis 1, sepsis 1 | TDS | 13 | 13 |

| 16 | 2011 | 50 | TG | 50 | 97 | TG | 75 | 75 | Pancreatitis 2, Hematoma 1, Bile leak 1, Infection 1, Perforation 1 | TG | 12 | 12 |

| 17 | 2012 | 40 | TG | 8 | 100 | TG | 44 | 73 | Pancreatitis 2, Abdominal pain 1, Pneumoperitoneum 1, Sepsis 1 | - | - | 13 |

| TDL | 16 | TD | 81 | |||||||||

| TDS | 13 | |||||||||||

| TJ | 3 | TJ | ||||||||||

| 18 | 2012 | 58 | TDL | 58 | 98 | TDL | 98 | 98 | Bile leakage 2 | TDL | 3 | 3 |

| 19 | 2013 | 14 | TG | 5 | 100 | TG | 100 | 100 | TG | 0 | 14 | |

| TDL | 4 | TDL | 100 | Biliary peritonitis 1 | TDL | 25 | ||||||

| TDS | 5 | TDS | 100 | Pancreatits 1 | TDS | 20 | ||||||

| 20 | 2015 | 20 | TG | 4 | 95 | TG | 75 | 80 | Hematoma 1, Pancreatitis 1 | TG | 50 | 15 |

| TDL | 5 | TDL | 60 | TDL | 0 | |||||||

| TDS | 10 | TDS | 100 | Pancreatitis 1 | TDS | 10 | ||||||

| Present study | - | 42 | TE | 11 | 98 | TE | 91 | 79 | Mediastinal emphysema 2 | TE | 18.1 | 16.7 |

| TG | 16 | TG | 75 | Retroperitoneal perforation 1 | TG | 6.2 | ||||||

| TDL | 7 | TDL | 57 | Cholangitis 1 | TDL | 16.7 | ||||||

| TDS | 4 | TDS | 75 | Peritonitis 1, Pancreatitis 1 | TDS | 50.0 | ||||||

| TJ | 4 | TJ | 100 | Peritonitis 1 | TJ | 25.0 | ||||||

| Total | 259 | TE | 11 | TE | 90.9 | 80.3 | 2 | TE | 18.1 | 11.6 | ||

| TG | 110 | TG | 73.6 | 11 | TG | 10.0 | ||||||

| TDL | 86 | TDL | 87.2 | 6 | TDL | 7.0 | ||||||

| TDS | 48 | TDS | 79.1 | 10 | TDS | 20.8 | ||||||

| TJ | 4 | TJ | 100.0 | 1 | TJ | 25.1 | ||||||

TE: transesophageal route, TG: transgastric route, TDL: transduodenal route long position, TDS: transduodenal route short position, TJ: transjejunum route

TG route EUS-RV was first described in 2004 (21). With this route, the intrahepatic bile duct (IHBD) of B2 or B3 is punctured from the cardia or lesser curvature of the stomach. The major advantage of this route is that puncture is made through the liver parenchyma, resulting in a tendency toward less bile leakage than with the TD route. Another advantage of this route is that the scope position is easy to maintain during scope changes. Given these advantages, we often choose this route.

In the present study, the success rate with the TG route was 75.0%, and the rate of complications was the lowest among the routes. B2 is easier for guide wire manipulation than B3. The TG route is known to be the safest route, therefore it is best to puncture B2 from the stomach. However, we sometimes may accidentally puncture the lower esophagus when attempting to puncture B2 from the stomach. With the TE route, it is easy to puncture B2; we therefore sometimes select the TE route for EUS-RV. However, two cases of mediastinal emphysema occurred among the patients who underwent TE route EUS-RV. We therefore avoid the TE route to prevent complications. In all cases in which moderate mediastinal emphysema occurred, the device that was passed along the aspiration route was bigger than a 19-gauge needle. Puncturing the esophagus must be avoided; however, if it occurs inadvertently and is noted later, nothing should be passed through the device except a needle.

TD route EUS-RV comprises two approach routes: TDL and TDS. TDL is the standard for EUS-guided choledochoduodenostomy (EUS-CDS) and is suitable for advancing the guide wire toward the proximal side. However, it is sometimes difficult to advance the guide wire toward the papilla. TDS involves puncturing from the second portion of the duodenum, between the superior duodenal angle (SDA) and papilla. The major advantage of this route is the ease of directing the guide wire toward the papilla. The disadvantages are the difficulty in maintaining the scope position and the risk of bile leakage. Kim et al. (15) reported that TDS EUS-RV after failed ERCP was successful in 12 of 15 patients (80%). Iwashita et al. (20) reported that TDS EUS-RV was the most appropriate technique given its high success rate (100%). However, it also had the highest complication rate (Table 7).

In the present study, only seven cases were treated via the TDL approach, and only four were treated via the TDS approach. We experienced kinking of a guide wire in each group. With the TDL approach, we were unable to shift the guide wire toward the papilla, and when we pulled the guide wire back into the needle, kinking occurred. With the TDS approach, the distance between the puncture site and the papilla was short, preventing us from pushing the guide wire. Therefore, when we pulled the guide wire back into the needle, kinking occurred. Both approaches required changing the approach route from the TD to the TG route due to an inability to advance the guide wire toward the papilla. The guide wire tends to stick because the sharp edge of the needle penetrates the covering membrane and sometimes strips it off. To avoid this, the guide wire should not be pulled back. If the angle of the needle and bile duct is not ideal and guide wire manipulation is difficult, changing the approach route may be effective, as seen in the present cases.

Four cases were treated via the TJ route in the present study. All four were altered anatomy cases, and the surgical procedure was total gastrectomy with Rouex-en-Y gastric bypass. The TJ route is similar to the TG route, so the scope position is easy to maintain during the procedure. The success rate was 100% in the TJ cases. However, we must take care to avoid trans-esophagus puncture as the TJ route involves puncturing the intrahepatic bile duct.

Other alternatives to biliary access after failed ERCP are PTBD, percutaneous rendezvous, and surgery. PTBD has been reported to have a high success rates of 87-100%. However, it is limited by external catheter placement and inherent morbidities and has a relatively high complication rate of 10-39% (23, 24). In cases of hepatic hilar stricture, multiple external catheters are sometimes necessary. Therefore, the patient's quality of life is markedly decreased. We therefore believe that EUS-RV is useful in cases of hepatic hilar stricture.

Percutaneous rendezvous is another salvage method in patients with failed ERCP, with reported clinical success and complication rates of 81-94.3% and 4.9-7.0%, respectively (25-27). The major disadvantage of this procedure is the requirement for both endoscopic and percutaneous interventions, which cannot always be performed simultaneously after failed ERCP cannulation if an interventional radiologist is not present. In contrast, EUS-RV can be performed in the same session as the failed ERCP if the procedure is anticipated and proper informed consent is obtained before the procedure. A randomized, controlled trial is required to compare the EUS-RV and percutaneous rendezvous techniques after failed ERCP.

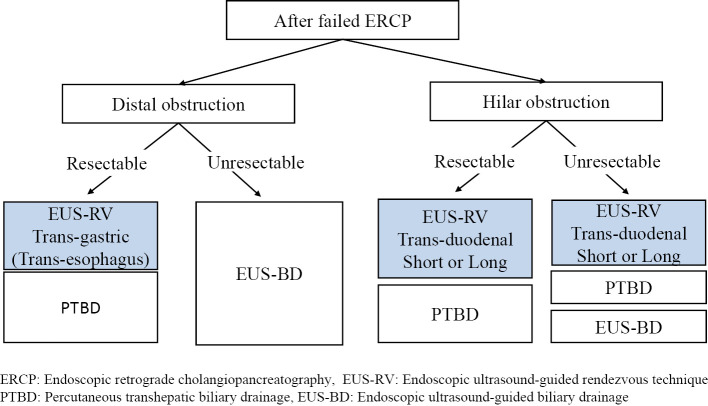

The overall success rate of EUS-RV is 80.3%, with a complication rate of 11.6% (Table 7). While EUS-RV is indeed a reasonable salvage method after failed ERCP, evidence remains insufficient to determine which approach route is the best. At present, the selection of the approach route differs among facilities. Taking the results of previous studies on EUS-RV into account, we have proposed a treatment algorithm using EUS-RV after failed ERCP, shown in Fig. 4. We believe that repeating ERCP on a different day is a reasonable alternative if immediate biliary therapy is not required in benign biliary disease. If EUS-RV is selected, we feel that the TD route is better for benign biliary diseases, such as stone removal.

Figure 4.

Proposed treatment procedure using endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage after failed ERCP.

The indications for EUS-guided biliary drainage should be limited to cases of unresectable malignant biliary obstruction (28). In patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction, such as those with pancreatic head cancer after failed ERCP, if the lesion is resectable and endoscopic access to the papilla is possible, we select EUS-RV. TDS might be difficult, as the scope position might be lost from D2 when the scope is pulled to puncture the EHBD above the obstruction. With TDL, it can be difficult to advance the guide wire toward the papilla. In the present study, the success rate of TE EUS-RV was high. However, this route carries a risk of mediastinal emphysema. As such, in distal malignant biliary obstruction cases, TG EUS-RV is preferable because of the low risk of biliary leakage.

In patients with hilar biliary obstruction, the TG or TE approach might be difficult, as the guide wire must pass through the stricture. Therefore, in hilar malignant biliary obstruction cases, TDS or TDL EUS-RV is preferable. In cases requiring multiple drainage, EUS-RV can be performed in the same session and can be used for multiple stenting at once. The selection of an approach route that maximizes the success rate is the most important factor for reducing the rate of complications associated with bile leakage, since proper biliary drainage can reduce bile leakage and treat bile peritonitis.

Our study has limitations because it was a retrospective, single-center study. A multicenter, randomized trial is essential to prove the superiority of this method.

Conclusion

EUS-RV provides safe and reliable transpapillary bile duct access after failed ERCP. EUS-RV may have an advantage in that it can be performed in the same session as ERCP as a one-step procedure without having to delay definitive therapy and without the pain and inconvenience of an external catheter. We believe that TG EUS-RV is preferable to other routes because of the low risk of complications and should therefore be performed when technically and anatomically possible. If a B2 puncture due to a TE approach is noted later, nothing should be passed through the device except for a needle in order to prevent complications. Further technological advances and the availability of dedicated tools are likely to improve the outcomes of EUS-RV. Large multicenter, randomized trials are needed to establish the therapeutic safety profiles of EUS-RV before this technique can be accepted as a standard alternative.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Sasahira N, Kawakami H, Isayama H, et al. Early use of double-guide wire technique to facilitate selective bile duct cannulation: the multicenter randomized controlled EDUCATION trial. Endoscopy 47: 421-429, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bailey AA, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, et al. A prospective randomized trial of cannulation technique in ERCP: effects on technical success and post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy 40: 296-301, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaffes AJ, Sriram PV, Rao GV, Santosh D, Reddy DN. Early institution of pre-cutting for difficult biliary cannulation: a prospective study comparing conventional vs. a modified technique. Gastrointest Endosc 62: 669-674, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, Hatfield AR, Cotton PB. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet 334: 1655-1660, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kama NA, Coskun T, Yuksek YN, Yazgan A. Factors affecting post-operative mortality in malignant biliary tract obstruction. Hepatogastroenterology 46: 103-107, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Winick AB, Waybill PN, Venbrux AC. Complications of percutaneous transhepatic biliary interventions. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 4: 200-206, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang KJ, Katz KD, Durbin TE, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc 40: 694-699, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seifert H, Faust D, Schmitt T, Dietrich C, Caspary W, Wehrmann T. Transmural drainage of cystic peripancreatic lesions with a new large-channel echo endoscope. Endoscopy 33: 1022-1026, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiersema MJ, Wiersema LM. Endosonography-guided celiac plexus neurolysis. Gastrointest Endosc 44: 656-662, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giovannini M, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Bories E, Lerong B, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bilioduodenal anastomosis: a new technique for biliary drainage. Endoscopy 33: 898-900, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mallery S, Matlock J, Freeman ML. EUS-guided rendezvous drainage of obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts: report of 6 cases. Gastrointest Endosc 59: 100-107, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc 71: 446-454, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brauer BC, Chen YK, Fukami N, Shah RJ. Single-operator EUS-guided cholangiopancreatography for difficult pancreaticobiliary access (with video). Gastrointest Endosc 70: 471-479, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maranki J, Hernandez AJ, Arslan B, et al. Interventional endoscopic ultrasound-guided cholangiography: long-term experience of an emerging alternative to percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. Endoscopy 41: 532-538, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim YS, Gupta K, Mallery S, Li R, Kinney T, Freeman ML. Endoscopic ultrasound rendezvous for bile duct access using a transduodenal approach: cumulative experience at a single center. A case series. Endoscopy 42: 496-502, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shah JN, Marson F, Weilert F, et al. Single-operator, single-session EUS-guided anterograde cholangiopancreatography in failed ERCP or inaccessible papilla. Gastrointest Endosc 75: 56-64, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iwashita T, Lee JG, Shinoura S, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous for biliary access after failed cannulation. Endoscopy 44: 60-65, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dhir V, Bhandari S, Bapat M, Maydeo A. Comparison of EUS guided rendezvous and precut papillotomy techniques for biliary access (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 75: 354-359, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kawakubo K, Isayama H, Sasahira N, et al. Clinical utility of an endoscopic ultrasound-guided rendezvous technique via various approach routes. Surg Endosc 27: 3437-3443, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Iwashita T, Yasuda I, Mukai T, et al. EUS-guided rendezvous for difficult biliary cannulation using a standardized algorithm: a multicenter prospective pilot study (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 83: 394-400, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kahaleh M, Yoshida C, Kane L, Yeaton P. Interventional EUS cholangiography: a report of five cases. Gastrointest Endosc 60: 138-142, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lai R, Freeman ML. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided bile duct access for rendezvous ERCP drainage in the setting of intradiverticular papilla. Endoscopy 37: 487-489, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van der Velden JJ, Berger MY, Bonjer HJ, Brakel K, Lameris JS. Percutaneous treatment of bile duct stones in patients treated unsuccessfully with endoscopic retrograde procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 51: 418-422, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Afghani E, et al. A comparative evaluation of EUS-guided biliary drainage and percutaneous drainage in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction and failed ERCP. Dig Dis Sci 60: 557-565, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Calvo MM, Bujanda L, Heras I, et al. The rendezvous technique for the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 54: 511-513, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wayman J, Mansfield JC, Matthewson K, Richardson DL, Griffin SM. Combined percutaneous and endoscopic procedures for bile duct obstruction: simultaneous and delayed techniques compared. Hepatogastroenterology 50: 915-918, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Neal CP, Thomasset SC, Bools D, et al. Combined percutaneous-endoscopic stenting of malignant biliary obstruction: results from 106 consecutive procedures and identification of factors associated with adverse outcome. Surg Endosc 24: 423-431, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hara K, Yama K, Mizuno N, et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage: Who, when, which, and how? World J Gastroenterol 22: 1297-1303, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]