Abstract

Aims

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection have a higher incidence of gastroduodenal diseases and therefore are recommended to receive eradication therapies. This study aimed to assess the efficacy of a 7-day standard triple therapy in patients with CKD (eGFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2) and to investigate the clinical factors influencing the success of eradication.

Methods

A total of 758 patients with H. pylori infection receiving a 7-day standard first-line triple therapy between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2014, were recruited. Patients were divided into two groups: CKD group (N = 130) and non-CKD group (N = 628).

Results

The eradication rates attained by the CKD and non-CKD groups were 85.4% and 85.7%, respectively, in the per-protocol analysis (p = 0.933). The eradication rate in CKD stage 3 was 84.5% (82/97), in stage 4 was 88.2% (15/17), and in those who received hemodialysis was 87.5% (14/16). There were no significant differences in the various stages of CKD (p = 0.982). The adverse events were similar between the two groups (3.1% versus 4.6%, p = 0.433). Compliance between the two groups was good (100.0% versus 99.8%, p = 0.649). There was no significant clinical factor influencing the H. pylori eradication rate in the non-CKD and CKD groups.

Conclusions

This study suggests that the H. pylori eradication rate and adverse rate in patients with CKD are comparable to those of non-CKD patients.

1. Introduction

A high incidence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Taiwan has been reported in the United States Renal Data System 2010 Annual Data Report [1]. This is a threat to the national health of the people. As per Hwang et al.'s report [2], the overall awareness of CKD is low in Taiwan: 9.7% for CKD stages 1–3 and 3.5% for stages 1–5. People need to be educated to address the risk factors associated with CKD, such as diabetes mellitus, glomerulonephritis, hypertension, older age, smoking, obesity, herbal medicine use, chronic lead exposure, and hepatitis C in public health program. Patients with CKD often have a higher incidence of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) than the general population, with a substantially increased PUD risk during the 10 years following diagnosis [3, 4]. Furthermore, CKD patients have higher peptic ulcer bleeding (PUB) complications, such as recurrent bleeding, infection, and mortality than the general population [5–8].

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) plays an important role in the development of chronic gastritis, gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and gastric cancer [9–12]. According to the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, although there is a lower H. pylori infection rate in patients with CKD (58.5%) and ESRD (56.2%) and PUD than in those with PUD without CKD (70.2%) [13], early H. pylori eradication (≤90 days) is highly suggested because it is associated with a protective role against the exacerbation of kidney malfunction and overall mortality [14].

The metabolism of certain drugs such as antibiotics could be altered in patients with CKD. Therefore, the influence on H. pylori eradication rate and adverse events of triple therapy need to be further studied. To our knowledge, the reports on H. pylori eradication in patients with CKD are scarce in Taiwan. This study aimed to assess the efficacy of a 7-day standard triple therapy in patients with CKD undergoing hemodialysis and to investigate the clinical factors influencing the success of eradication.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

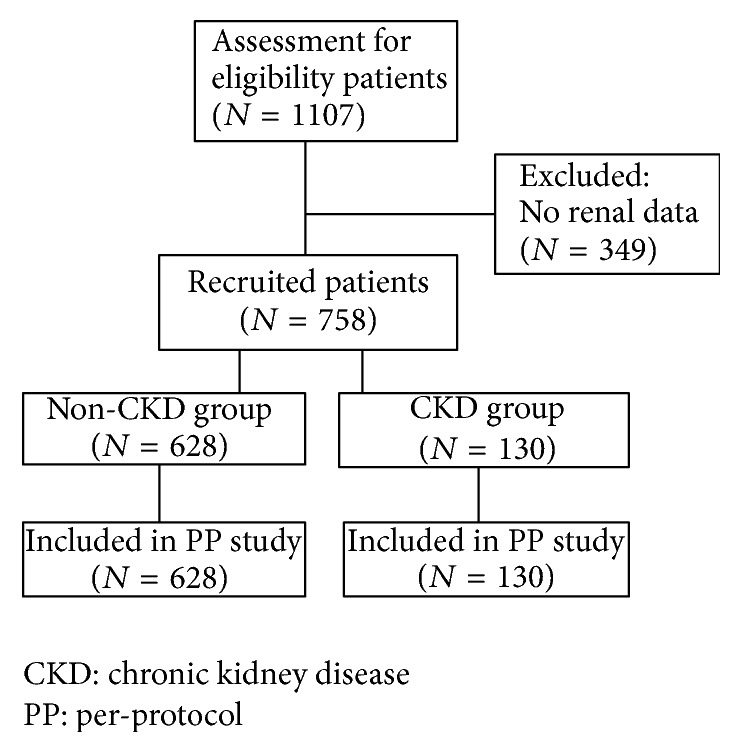

A total of 1107 patients infected with H. pylori receiving a first-line triple therapy were retrospectively studied between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2014, at outpatient clinics in Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan. Of these patients, 758 were recruited in the per-protocol (PP) study after excluding 349 patients due to incomplete chart recording. All patients were at least 18 years of age and had received endoscope examinations that showed either peptic ulcers or gastritis. Patients were then divided into two groups: CKD group (n = 130) and non-CKD group (n = 628) (Figure 1). Patients in the non-CKD group received a standard triple therapy [proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) twice daily, 500 mg clarithromycin twice daily, and 1 g amoxicillin twice daily for 7 days], whereas ESRD patients in the CKD group received PPI twice daily and half the dose of clarithromycin and amoxicillin twice daily for 7 days.

Figure 1.

Disposition of patients.

Based on the revised 4-variable MDRD Study equation [15], all individuals with a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 for 3 months were classified as having CKD, irrespective of the presence or absence of kidney damage. The rationale for including these individuals was that reduction in kidney function to this or lower level represents loss of half or more of the adult level of normal kidney function, which may be associated with a number of complications such as the development of cardiovascular diseases [16].

H. pylori eradication failure was confirmed if patients had either one positive 13C-UBT or any two positive results of the rapid urease test, histology, and culture after first-line eradication therapy. According to our hospital requirements, all registered patients were followed up to assess drug compliance and adverse effects as soon as they finished their medications. These patients then underwent either an endoscopy or a urea breath test 4–8 weeks later. Poor compliance was defined as failure to finish 80% of all medication due to adverse effects [17].

Demographic information including age, sex, social history of smoking, alcohol consumption, previous peptic ulcer history, and laboratory data (AST, ALT, total bilirubin, albumin, BUN, Cr, sodium, potassium, calcium, hemoglobin, cholesterol, and triglyceride) were collected via electrical medical records. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (IRB 201700772B0). The Ethics Committee waived the requirement for informed consent, and each patient's medical records were anonymized and not identified before access. All patients provided their written informed consent before endoscopic interventions.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome variables were eradication rate, presence of adverse events, and level of patient compliance. Using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 18 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), Chi-square tests with or without Yates' correction for continuity and Fisher's exact tests were used when appropriate to compare the major outcomes between groups. Eradication rates were analyzed by PP approaches. The PP analysis excluded patients with unknown H. pylori status following therapy and those with major protocol violations. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To determine the independent factors that affected treatment response, the clinical and laboratory parameters were analyzed by univariate and multivariate analyses.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows patient flowchart. The demographic data of the two groups are summarized in Table 1. In comparison to patients in the non-CKD group, patients in the CKD group were older (68.6 ± 10.0 versus 58.2 ± 11.3, p < 0.001) and had a higher incidence of peptic ulcer history (30% versus 16.9%, p = 0.001), higher BUN levels (33.2 ± 22.2 mg/dl versus 14.2 ± 20.0 mg/dl, p < 0.001), higher potassium levels (5.9 ± 2.7 mEq/L versus 4.2 ± 2.9 mEq/L, p = 0.024), lower chloride levels (97.5 ± 24.4 mEq/L versus 104.5 ± 10.4 mEq/L, p = 0.029), lower hemoglobin levels (11.4 ± 2.2 g/dL versus 13.7 ± 3.1 g/dL, p < 0.001), and lower cholesterol levels (168.1 ± 29.5 mg/dL versus 189.2 ± 38.8 mg/dL, p = 0.001). The eradication rates attained by the CKD and non-CKD groups were 85.4% (111/130) and 85.7% (538/628), respectively, in the PP analysis (p = 0.933) (Table 2). The eradication rates in the different stages of CKD were as follows: 84.5% in stage 3, 88.2% in stage 4, and 87.5% in hemodialysis (p = 0.982) (Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographic data and endoscopic appearances of the two patient groups.

| CKD (n = 130) n (%) |

Control non-CKD (n = 628) n (%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) (mean ± SD) | 68.6 ± 10.0 | 58.2 ± 11.3 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male/female) | 53/77 | 303/325 | 0.120 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 14 (10.8) | 94 (15.0) | 0.213 |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | 14 (10.8) | 101 (16.1) | 0.124 |

| Previous history of peptic ulcer, n (%) | 39 (30.0) | 106 (16.9) | 0.001 |

| Endoscopic findings, n (%) | |||

| Gastritis | 35 (26.9) | 214 (34.1) | |

| Gastric ulcer | 60 (46.2) | 190 (30.3) | 0.002 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 22 (16.9) | 169 (26.9) | |

| Gastric and duodenal ulcer | 13 (10.0) | 55 (8.8) | |

| Laboratory data (mean ± SD) | |||

| AST (U/L) | 29.1 ± 13.8 | 28.8 ± 21.4 | 0.921 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25.2 ± 15.4 | 31.4 ± 29.4 | 0.051 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 0.564 |

| Albumin (g/dl) | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 0.089 |

| Total protein (g/dl) | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 7.7 ± 6.8 | 0.716 |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 33.2 ± 22.2 | 14.2 ± 20.0 | <0.001 |

| Na (mEq/L) | 137.0 ± 18.9 | 139.3 ± 11.2 | 0.231 |

| K (mEq/L) | 5.9 ± 2.7 | 4.2 ± 2.9 | 0.024 |

| Ca (mEq/L) | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 11.0 ± 13.0 | 0.480 |

| Cl (mEq/L) | 97.5 ± 24.4 | 104.5 ± 10.4 | 0.029 |

| GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 39.0 ± 16.6 | 90.1 ± 19.3 | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.4 ± 2.2 | 13.7 ± 3.1 | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 168.1 ± 29.5 | 189.2 ± 38.8 | 0.001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | 152.6 ± 80.0 | 126.4 ± 79.9 | 0.055 |

CKD: chronic kidney disease, AST: aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: alanine aminotransferase, BUN: blood urea nitrogen, GFR: glomerular filtration rate, Na: sodium, K: potassium, Cl: chloride, and Ca: calcium.

Table 2.

Major outcomes of eradication therapy.

| Eradication rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CKD (n = 130) | Non-CKD (n = 628) | p value | |

| Per-protocol | 85.4% (111/130) | 85.7% (538/628) | 0.933 |

| Adverse event | 3.1% (4/130) | 4.6% (29/628) | 0.433 |

| Compliance | 100.0% (130/130) | 99.8% (627/628) | 0.649 |

CKD: chronic kidney disease.

Table 3.

Helicobacter pylori eradication rates in different stages of kidney disease.

| CKD stage | Stage 3 (n = 97) |

Stage 4 (n = 17) |

Hemodialysis (n = 16) | Total (n = 130) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eradication rate | 84.5% (82) | 88.2% (15) | 87.5% (14) | 85.4% (111) | 0.982 |

CKD: chronic kidney disease.

3.1. Adverse Events and Compliance

Since amoxicillin and clarithromycin are primarily eliminated via the renal route, these antibiotics need a dosage adjustment based on GFR in patients with renal failure. Therefore, we prescribed the half-dose triple therapy with clarithromycin and amoxicillin to eradicate H. pylori in patients with ESRD. The adverse events were similar between the two groups (3.1% versus 4.6%, p = 0.433) (Table 2). These adverse events included abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, dizziness, headache, and nausea/vomiting. However, these adverse events were mild and did not disturb the patients' daily activities. Both groups had good drug compliances (100% in the CKD group versus 99.8% in the non-CKD group, p = 0.649). Only one patient did not complete the triple eradication therapy in the non-CKD group: a 68-year-old male patient who stopped taking medications after developing severe vomiting following the triple eradication therapy at day 3.

3.2. Factors Influencing the Efficacy of Anti-H. pylori Therapy

In the univariate analysis of the CKD and non-CKD groups, there was no significant clinical factor influencing the H. pylori eradication rate in patients with CKD (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of the clinical factors influencing the efficacy of H. pylori eradication.

| Principle parameter | CKD (n = 130) | p value | Non-CKD (n = 628) | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | Eradication rate (%) | Case number | Eradication rate (%) | ||||

| Age | ≥60 years | 90/107 | 84.1 | 0.376 | 216/309 | 69.9 | 0.397 |

| <60 years | 21/23 | 91.3 | 277/319 | 86.8 | |||

| Sex | Female | 66/77 | 85.7 | 0.898 | 286/325 | 88.0 | 0.084 |

| Male | 45/53 | 84.9 | 252/303 | 83.2 | |||

| Smoking | (−) | 98/116 | 84.5 | 0.402 | 460/534 | 86.1 | 0.420 |

| (+) | 13/14 | 92.9 | 78/94 | 83.0 | |||

| Alcohol consumption | (−) | 98/116 | 84.5 | 0.402 | 455/527 | 86.3 | 0.274 |

| (−) | 13/14 | 92.9 | 83/101 | 82.2 | |||

| Previous history of peptic ulcer | (−) | 98/116 | 84.5 | 0.871 | 448/522 | 85.8 | 0.806 |

| (+) | 13/14 | 92.9 | 90/106 | 84.9 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Laboratory data | |||||||

| Na (mEq/L) | ≥130 | 44/53 | 83.0 | 0.524 | 285/327 | 87.2 | 0.348 |

| <130 | 2/2 | 100 | 6/6 | 100 | |||

| K (mEq/L) | ≥5 | 10/11 | 90.9 | 0.616 | 6/6 | 100 | 0.337 |

| <5 | 46/54 | 85.2 | 312/360 | 86.7 | |||

| Ca (mEq/L) | ≥8 | 25/29 | 86.2 | 0.574 | 176/195 | 90.3 | 0.743 |

| <8 | 2/2 | 100 | 1/1 | 100 | |||

| Albumin (g/dl) | ≥3.5 | 29/34 | 85.3 | 0.679 | 194/218 | 89.0 | 0.321 |

| <3.5 | 1/1 | 100 | 8/8 | 100 | |||

| BUN (mg/dl) | ≥20 | 37/46 | 76.1 | 0.102 | 29/32 | 90.6 | 0.552 |

| <20 | 21/22 | 95.4 | 253/291 | 86.9 | |||

| GFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) | ≥30 | 82/97 | 84.5 | 0.639 | 538/628 | 85.7 | — |

| <30 | 29/33 | 87.9 | 0 | ||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | ≥200 | 6/6 | 100 | 0.237 | 97/110 | 88.2 | 0.776 |

| <200 | 29/36 | 80.6 | 175/201 | 87.1 | |||

| Triglyceride (mg/dl) | ≥150 | 14/17 | 82.4 | 0.687 | 76/85 | 89.4 | 0.419 |

| <150 | 20/23 | 87.0 | 183/213 | 85.9 | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ≥10 | 67/79 | 84.8 | 0.922 | 408/473 | 86.3 | 0.745 |

| <10 | 21/25 | 84.0 | 30/34 | 88.2 | |||

CKD: chronic kidney disease, BUN: blood urea nitrogen, GFR: glomerular filtration rate, Na: sodium, K: potassium, Cl: chloride, and Ca: calcium.

4. Discussion

Patients with chronic renal failure generally have a higher incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms than the general population, which is associated with not only H. pylori infection but also high urea levels, impairment of gastrointestinal motility, amyloid protein deposition [18, 19], and decreased sensory disturbance. Furthermore, patients with CKD are at a higher risk of gastric mucosal damage than those with normal renal function because of coexisting comorbidities such as diabetes and coronary artery diseases [20, 21], hypergastrinemia [22], and poor systemic circulation, resulting in enhanced inflammation of the gastrointestinal mucosa.

Till now, the eradication of H. pylori infection was recommended as a critical step in preventing and treating PUD not only in patients with normal renal function but also in those with renal failure [23–25]. Although triple regimen showed disappointing results (80%) in Taiwan due to high clarithromycin resistance (22%) and is not recommended by Taiwan consensus, it still remains the most widely used 1st-line H. pylori eradication therapy [26, 27]. Since medical expenses in Taiwan are generally covered by the Taiwanese National Health Insurance administration, standard triple therapy is still the recommended first-line empiric regimen. Therefore, we recommend replacing this standard triple therapy with a 4-drug combination treatment. This course may be sequential, concomitant, or hybrid and may involve extension of the triple therapy to 14 days to improve the eradication rates [28–31].

Several studies reported various eradication rates by triple therapy regimens ranging from 72.7% to 94.1% in hemodialysis-dependent patients [32–35]. In the clinical trial by Makhlough et al., the eradication rate of a standard triple therapy in CKD stage 3 was 50% (1/2), in CKD stage 4 was 75% (3/4), and in hemodialysis was 80% (12/15) [36]. In our study, which included larger case numbers than previous studies on CKD, the eradication rate in CKD stage 3 was 84.5% (82/97), in CKD stage 4 was 88.2% (15/17), and in hemodialysis was 87.5% (14/16). There is no significant difference in the various stages of CKD (p = 0.982). Therefore, the successful rate of eradication was similar in the different stages of CKD.

In this study, the adverse events were similar between the two groups (3.1% versus 4.6%, p = 0.433). The most common side effect was abdominal bloating. The physician should not be afraid of the adverse effect of these anti-H. pylori drugs. Instead, they should be more motivated to eradicate H. pylori in patients with CKD considering the potential complications and mortality in these patients who suffer from PUB [13, 14]. With respect to the dosage, Ehsani Ardakani et al. reported that half-dose triple therapy with clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and omeprazole is as effective as full-dose triple therapy in patients with ESRD [37]. Also, they found that more patients developed a bitter taste in their mouths as well as abdominal distension in the full-dose group (73.6% versus 39.7%, p = 0.014) compared with the half-dose group (41.2% and 18.3%, p = 0.04). To lower toxicity, adverse events, and cost of the half-dose regimen in this subset of patients, adjusting the dose of the eradication protocol according to the renal function of patient is advised [38, 39].

There are some limitations to this study. First, it is a single-center retrospective study. Second, the number of patients with CKD is small. Third, no information on antibiotic resistance to H. pylori was available. H. pylori culture was not routinely conducted before triple therapy. Fourth, the follow-up of H. pylori eradication status was conducted 4–8 weeks after therapy. Checking an effective response at 4 weeks seemed too early since this may lead to pseudonegative results especially at 4 weeks after the end of therapy.

5. Conclusion

This study suggests that H. pylori eradication rate and adverse events in the CKD group were comparable to those of the non-CKD group. Neither group achieved >90% eradication rates with the standard triple therapy. Therefore, further studies are warranted to search for an optimal regimen for treating patients with CKD and H. pylori infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Miss Ching-Yi Lin for her assistance in this study.

Contributor Information

Chen-Hsiang Lee, Email: lee900@adm.cgmh.org.tw.

Seng-Kee Chuah, Email: chuahsk@seed.net.tw.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Collins A. J., Foley R. N., Herzog C., et al. Annual Data Report 2010. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2011;57 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.10.007. A8, e1-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hwang S.-J., Tsai J.-C., Chen H.-C. Epidemiology, impact and preventive care of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan. Nephrology. 2010;15(supplement 2):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrow D., Delegge M. H. Risk factors for gastrointestinal ulcer disease in the US population. Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 2010;55(1):66–72. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0708-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang C.-C., Muo C.-H., Wang I.-K., et al. Peptic ulcer disease risk in chronic kidney disease: Ten-year incidence, ulcer location, and ulcerogenic effect of medications. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087952.e87952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang J.-Y., Ho K.-Y., Yeoh K.-G., et al. Peptic ulcer and gastritis in uraemia, with particular reference to the effect of Helicobacter pylori infection. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 1999;14(8):771–778. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverstein F. E., Gilbert D. A., Tedesco F. J., Buenger N. K., Persing J. The national ASGE survey on upper gastrointestinal bleeding. II. Clinical prognostic factors. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 1981;27(2):80–93. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(81)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branicki F. J., Boey J., Fok P. J., et al. Bleeding duodenal ulcer. A prospective evaluation of risk factors for rebleeding and death. Annals of Surgery. 1990;211(4):411–418. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199004000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang C.-M., Hsu C.-N., Tai W.-C., et al. Taiwan Acid-Related Disease (TARD) Study Group. Risk factors influencing the outcome of peptic ulcer bleeding in chronic kidney disease after initial endoscopic hemostasis: A nationwide cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95, article e4795 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuah S.-K., Tsay F.-W., Hsu P.-I., Wu D.-C. A new look at anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2011;17(35):3971–3975. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i35.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasbarrini G., Pretolani S., Bonvicini F., et al. A population based study of Helicobacter pylon infection in a European country: The San Marino study. Relations with gastrointestinal diseases. Gut. 1995;36(6):838–844. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.6.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suerbaum S., Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(15):1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talley N. J., Fock K.-M., Moayyedi P. Gastric Cancer Consensus conference recommends Helicobacter pylori screening and treatment in asymptomatic persons from high-risk populations to prevent gastric cancer. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;103(3):510–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang S.-S., Hu H.-Y. Lower Helicobacter pylori infection rate in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease patients with peptic ulcer disease. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 2014;77(7):354–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J.-W., Hsu C.-N., Tai W.-C., et al. The association of helicobacter pylori eradication with the occurrences of chronic kidney diseases in patients with peptic ulcer diseases. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164824.e0164824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2002;39(Suppl 1):S1–S266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Clinical Guideline Centre (UK) Chronic Kidney Disease (Partial Update): Early Identification And Management of Chronic Kidney Disease in Adults in Primary And Secondary Care. london, UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tai W.-C., Liang C.-M., Lee C.-H., et al. Seven-day nonbismuth containing quadruple therapy could achieve a grade a success rate for first-line helicobacter pylori eradication. BioMed Research International. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/623732.623732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoonjans R., Van Vlem B., Vandamme W., et al. Dyspepsia and gastroparesis in chronic renal failure: The role of Helicobacter pylori. Clinical Nephrology. 2002;57(3):201–207. doi: 10.5414/CNP57201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strid H., Simrén M., Stotzer P.-O., Abrahamsson H., Björnsson E. S. Delay in gastric emptying in patients with chronic renal failure. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2004;39(6):516–520. doi: 10.1080/00365520410004505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block G. A., Raggi P., Bellasi A., Kooienga L., Spiegel D. M. Mortality effect of coronary calcification and phosphate binder choice in incident hemodialysis patients. Kidney International. 2007;71(5):438–441. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakamura S., Sasaki O., Nakahama H., Inenaga T., Kawano Y. Clinical characteristics and survival in end-stage renal disease patients with arteriosclerosis obliterans. American Journal of Nephrology. 2002;22(5-6):422–428. doi: 10.1159/000065267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gür G., Boyacioglu S., Gül Ç., et al. Impact of helicobacter pylori infection on serum gastrin in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation . 1999;14(11):2688–2691. doi: 10.1093/ndt/14.11.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang S.-S., Hu H.-Y. Association between early helicobacter pylori eradication and a lower risk of recurrent complicated peptic ulcers in end-stage renal disease patients. Medicine (United States) 2015;94(1):p. e370. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cocchiara G., Romano M., Buscemi G., Maione C., Maniaci S., Romano G. Advantage of Eradication Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Before Kidney Transplantation in Uremic Patients. Transplantation Proceedings. 2007;39(10):3041–3043. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.07.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itatsu T., Miwa H., Nagahara A., et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in hemodialysis patients. Renal Failure. 2007;29(1):97–102. doi: 10.1080/08860220601039122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheu B.-S., Wu M.-S., Chiu C.-T., et al. Consensus on the clinical management, screening-to-treat, and surveillance of Helicobacter pylori infection to improve gastric cancer control on a nationwide scale. Helicobacter. 2017;22(3) doi: 10.1111/hel.12368.e12368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsay F.-W., Tseng H.-H., Hsu P.-I., et al. Sequential therapy achieves a higher eradication rate than standard triple therapy in Taiwan. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2012;27(3):498–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gatta L., Vakil N., Vaira D., Scarpignato C. Global eradication rates for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of sequential therapy. British Medical Journal. 2013;347(7920) doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4587.f4587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liou J.-M., Chen C.-C., Chen M.-J., et al. TaiwanHelicobacter consortium. sequential versus triple therapy for the first‐line treatment of helicobacter pylori: a multicentre, open‐label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2013;381:205–213. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gisbert J. P., Calvet X. Update on non-bismuth quadruple (concomitant) therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 2012;5(1):23–34. doi: 10.2147/ceg.s25419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu P.-I., Wu D.-C., Wu J.-Y., Graham D. Y. Modified sequential Helicobacter pylori therapy: proton pump inhibitor and amoxicillin for 14 days with clarithromycin and metronidazole added as a quadruple (hybrid) therapy for the final 7 days. Helicobacter. 2011;16(2):139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00828.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y.-L., Sheu B.-S., Huang J.-J., Yang H.-B. Noninvasive stool antigen assay can effectively screen Helicobacter pylori infection and assess success of eradication therapy in hemodialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2001;38(1):98–103. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsukada K., Miyazaki T., Katoh H., et al. Seven-day triple therapy with omeprazole, amoxycillin and clarithromycin for Helicobacter pylori infection in haemodialysis patients. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2002;37(11):1265–1268. doi: 10.1080/003655202761020524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sezer S., Ibiş A., Özdemir B. H., et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with nutritional status in hemodialysis patients. Transplantation Proceedings. 2004;36(1):47–49. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang W.-C., Yi J.-O., Park H.-S., et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a 7-day low-dose triple therapy in hemodialysis patients. ClinExpNephrol. 2010;14:469–473. doi: 10.1007/s10157-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makhlough A., Fakheri H., Farkhani A., et al. A comparison between standard triple therapy and sequential therapy on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in uremic patients: a randomized clinical trial. Advanced Biomedical Research. 2014;3(1):p. 248. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.146372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.EhsaniArdakani M. J., Aghajanian M., Nasiri A. A., Mohaghegh-Shalmani H., Zojaji H., Maleki I. Comparison of half-dose and full-dose triple therapy regimens forHelicobacter pylori eradication in patients with end-stage renal disease. GastroenterolHepatol Bed Bench. 2014;7:151–155. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spyker D. A., Rugloski R. J., Vann R. L., O'Brien W. M. Pharmacokinetics of amoxicillin: dose dependence after intravenous, oral, and intramuscular administration. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1977;11(1):132–141. doi: 10.1128/AAC.11.1.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodvold K. A. Clinical pharmacokinetics of clarithromycin. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 1999;37(5):385–398. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199937050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]