Abstract

Background:

Prior studies have reported controversial conclusions regarding the risk of adverse cardiovascular events in patients using proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) combined with clopidogrel therapy, causing much uncertainty in clinical practice. We sought to evaluate the safety of PPIs use among high-risk cardiovascular patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in a long-term follow-up study.

Methods:

A total of 7868 consecutive patients who had undergone PCI and received dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) at a single center from January 2013 to December 2013 were enrolled. Adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-induced platelet aggregation inhibition was measured by modified thromboelastography (mTEG) in 5042 patients. Propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to control differing baseline factors. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to evaluate the 2-year major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs), as well as individual events, including all-cause death, myocardial infarction, unplanned target vessel revascularization, stent thrombosis, and stroke.

Results:

Among the whole cohort, 27.2% were prescribed PPIs. The ADP-induced platelet aggregation inhibition by mTEG was significantly lower in PPI users than that in non-PPI users (42.0 ± 30.9% vs. 46.4 ± 31.4%, t = 4.435, P < 0.001). Concomitant PPI use was not associated with increased MACCE through 2-year follow-up (12.7% vs. 12.5%, χ2 = 0.086, P = 0.769). Other endpoints showed no significant differences after multivariate adjustment, regardless of PSM.

Conclusion:

In this large cohort of real-world patients, the combination of PPIs with DAPT was not associated with increased risk of MACCE in patients who underwent PCI at up to 2 years of follow-up.

Keywords: Clopidogrel, Drug Interactions, Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Proton-pump Inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) mitigates the risk of stent thrombosis (ST) and ischemic events in patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).[1] Nonetheless, antiplatelet therapy is also associated with increased bleeding risk, and gastrointestinal bleeding accounts for a notable proportion of the bleeding complications of DAPT and probably leads to DAPT cessation, which further increases adverse cardiovascular events.[2] Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) are often concomitantly prescribed to patients in combination with DAPT to help reduce the occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding.[3] However, several pharmacokinetic studies and observational studies have demonstrated potential interaction of PPIs with clopidogrel via competition with liver cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (especially CYP2C19), leading to reduced antiplatelet activity and increased ischemic events.[2,4,5,6,7,8] New evidences showed that the interaction may have no clinical significance.[9,10] Limited by the controversial conclusions, the 2016 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline on DAPT in patients with coronary artery disease suggested no routine PPI use in the setting of DAPT.[11] However, the 2017 European Society of Cardiology focused update on DAPT in coronary artery disease recommended PPI in combination with DAPT.[1] Therefore, we performed a large prospective observational study to evaluate the interaction between PPIs and DAPT among high-risk cardiovascular patients who underwent PCI from both pharmacodynamic and clinical aspects. Propensity score matching (PSM) was implemented to eliminate the covariate imbalance.

METHODS

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Fuwai Hospital Institutional Ethical Review Board. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients or their guardians, in the case of children, prior to their enrollment in this study.

Study population

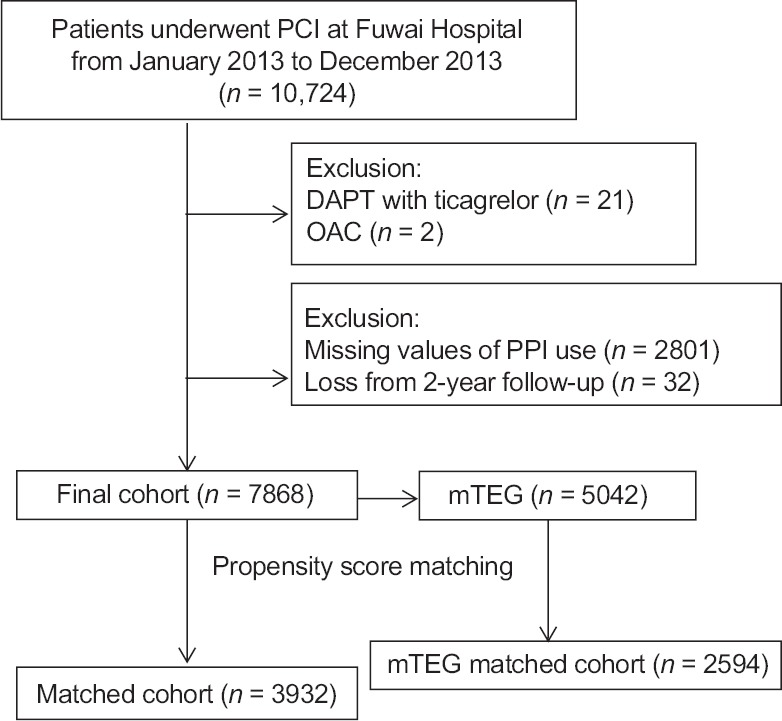

All 10,724 consecutive patients from a single center (Fu Wai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Beijing, China) who underwent PCI throughout 2013 were enrolled in the study. Of these, 21 patients were prescribed aspirin and ticagrelor, and two patients were prescribed oral anticoagulant after PCI. Ticagrelor is a P2Y12 inhibitor that does not need biotransformation and has no effect on the CYP2C19 isoenzyme. Thus, only patients treated with aspirin and clopidogrel were included (n = 10,701). Patients with missing values of PPI use and loss of follow-up were excluded [n = 2833, Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Patient flowchart for the study cohort. PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; DAPT: Dual antiplatelet therapy; OAC: Oral anticoagulants; PPI: Proton-pump inhibitors; mTEG: Modified thromboelastograph.

Procedure and medications

The PCI strategy and stent type were determined by the physician's discretion. Before the procedure, all patients who had not taken long-term aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors received oral 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel. After the procedure, patients were to take aspirin 100 mg/d indefinitely and clopidogrel 75 mg/d for at least 1 year after PCI. PPI use was determined at the physician's discretion and was recorded at the time of PCI. The specific PPI was not reported.

Data collection and study endpoints

Baseline clinical characteristics, past medical history, laboratory tests, PCI data, and discharge medications were collected. All patients were evaluated at a clinic visit or by phone at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months. The average follow-up was 875.3 days. The primary endpoint was major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) during follow-up. MACCE were defined as a composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction (MI), unplanned target vessel revascularization (TVR), ST, and stroke. MI was defined according to the clinical and laboratory parameters established in the third universal definition of MI.[12] Unplanned TVR was defined as any repeat PCI or surgical bypass of any segment of the target vessel for ischemic symptoms and events. ST was defined by the Academic Research Consortium, and definite and probable ST were included in the analysis.[13] Secondary endpoints included each component of the primary endpoint. Bleeding was quantified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium Definition (BARC) criteria, and types 2, 3, and 5 were included in the analysis.[14] Major bleeding was defined as type 3 and 5 according to the BARC criteria. All endpoints were adjudicated centrally by two independent cardiologists, and disagreement was resolved by consensus.

Blood sampling

According to the physician's discretion, platelet aggregation inhibition tests were performed by modified thromboelastography (mTEG, Haemonetics Corp., Massachusetts, USA). Blood was collected at least 6 h after using clopidogrel in a Vacutainer tube containing 3.2% trisodium citrate. The Vacutainer tube was filled to capacity and inverted 3–5 times to ensure complete mixing of the anticoagulant. The mTEG instrument uses 4 channels to detect the effects of antiplatelet therapy acting via the arachidonic acid and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) pathways.[15] An mTEG hemostasis analyzer (Haemonetics Corp., Massachusetts, USA) and automated analytical software (Haemonetics Corp., Massachusetts, USA) were used to measure the physical properties. ADP inhibition % of <30% was considered a clopidogrel low response (CLR).[16]

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentages) and were compared using the Chi-squared test. Continuous variables are presented as the means ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) and were compared using the t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test. Hazard ratios (HRs) are presented with the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and a two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kaplan-Meier analysis was applied to evaluate endpoints. The covariates for Cox proportional regression were those variables with significant differences at baseline or important clinical meaning.

To minimize the effect of confounding factors caused by differences in baseline characteristics between patients with and without PPI use, PSM was performed for both the whole population and the mTEG population. A propensity score was estimated for each patient using a logistic regression model. Patients were matched on estimated propensity scores, with replacement, using a nearest neighbor approach. A caliper width of 0.02 was used. For the total population, the dependent variable was PPI use, and the covariates were age, gender, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, prior cerebrovascular disease, prior MI, prior PCI, prior coronary artery bypass grafting, acute MI, ejection fraction, Killip class, estimated glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin, intra-aortic balloon pump, and warfarin use. For the mTEG population, the dependent variable was PPI use, and the covariates were age, gender, prior cerebrovascular disease, prior MI, prior PCI, acute MI, ejection fraction, estimated glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin, and intra-aortic balloon pump.

RESULTS

Study population and demographics

Among 7868 enrolled patients, 2142 (27.2%) patients were prescribed PPIs. PPI users were older and were more likely to be female with a higher rate of cerebrovascular disease and a lower rate of prior MI. These individuals presented more frequently with acute MI and needed more intra-aortic balloon pump support. With respect to laboratory tests, PPI-treated patients had worse heart and renal function, lower hemoglobin levels, and a faster erythrocyte sedimentation rate. PPI users received warfarin more often than non-PPI users. There were significant differences in the baseline levels between the two groups. After PSM, 1966 patients had an estimated propensity score that matched within the 0.02 caliper to 1966 patients without PPI use [Table 1].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics among all patients according to PPI use before and after PSM

| Parameters | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPI (n = 2142) | No PPI (n = 5726) | Statistics | P | PPI (n = 1966) | No PPI (n = 1966) | Statistics | P | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Gender (female) | 527 (24.6) | 1145 (20.0) | 19.768* | <0.001 | 485 (24.7) | 447 (22.7) | 2.031* | 0.154 |

| Age (years) | 60.2 ± 10.6 | 57.7 ± 10.3 | −9.402† | <0.001 | 60.2 ± 10.5 | 60.8 ± 9.9 | 1.908† | 0.057 |

| Past medical history | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 1362 (63.6) | 3653 (63.8) | 0.030* | 0.862 | 1259 (64.0) | 1286 (65.4) | 0.812* | 0.368 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1417 (66.2) | 3870 (67.6) | 1.453* | 0.228 | 1316 (66.9) | 1409 (71.7) | 10.340* | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 615 (28.7) | 1773 (31.0) | 3.742* | 0.053 | 571 (29.0) | 595 (30.3) | 0.702* | 0.402 |

| PAD | 66 (3.1) | 137 (2.4) | 2.941* | 0.086 | 63 (3.2) | 71 (3.6) | 0.494* | 0.482 |

| Prior CVD | 289 (13.5) | 570 (10.0) | 20.057* | <0.001 | 261 (13.3) | 260 (13.2) | 0.002* | 0.962 |

| Prior MI | 430 (20.1) | 1586 (27.7) | 47.539* | <0.001 | 404 (20.5) | 666 (33.9) | 88.138* | <0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 591 (27.6) | 1653 (28.9) | 1.248* | 0.264 | 500 (25.4) | 960 (48.8) | 230.530* | <0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 85 (3.9) | 276 (4.8) | 2.883* | 0.090 | 81 (4.1) | 152 (7.7) | 22.998* | <0.001 |

| Admission features | ||||||||

| Acute MI | 598 (27.9) | 1224 (21.4) | 37.488* | <0.001 | 486 (24.7) | 432 (22.0) | 4.144* | 0.042 |

| LVEF, % | 61.5 ± 7.9 | 62.2 ± 7.6 | 3.360† | 0.001 | 62.0 ± 7.7 | 61.6 ± 7.9 | −1.623† | 0.105 |

| Killip class ≥2 | 45 (2.1) | 72 (1.3) | 7.570* | 0.006 | 30 (1.5) | 37 (1.9) | 0.744* | 0.388 |

| SAP (mmHg) | 126.1 ± 17.5 | 126.3 ± 16.8 | 0.346† | 0.729 | 126.3 ± 17.4 | 126.9 ± 16.5 | 1.133† | 0.257 |

| Current smoking | 1247 (58.2) | 3384 (59.1) | 0.501* | 0.479 | 1134 (57.7) | 1109 (56.4) | 0.649* | 0.421 |

| Laboratory test | ||||||||

| BNP (pg/ml) | 649.8 (480.3–912.7) | 616.6 (474.9–847.3) | −2.879‡ | 0.004 | 649.3 (479.9–649.3) | 640.2 (490.6–895.6) | −0.124‡ | 0.901 |

| eGFR (ml/min) | 88.9 ± 15.9 | 91.8 ± 15.1 | 7.209† | <0.001 | 89.2 ± 15.5 | 88.6 ± 15.6 | −1.203† | 0.229 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 7 (3–16) | 7 (3–14) | −2.780‡ | 0.005 | 7 (3–16) | 7 (3–14) | −0.383‡ | 0.702 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 141.4 ± 16.0 | 144.2 ± 15.1 | 6.970† | <0.001 | 141.4 ± 16.0 | 141.4 ± 15.3 | 0.070† | 0.944 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||||||

| Thrombolysis | 85 (4.0) | 194 (3.4) | 1.534* | 0.215 | 79 (4.0) | 63 (3.2) | 1.870* | 0.171 |

| Syntax score | ||||||||

| 0–22 | 1871 (87.3) | 5078 (88.7) | 2.773* | 0.250 | 1726 (87.9) | 1800 (91.6) | 13.953* | 0.001 |

| 23–32 | 234 (10.9) | 555 (9.7) | 206 (10.5) | 145 (7.4) | ||||

| ≥33 | 37 (1.7) | 93 (1.6) | 31 (1.6) | 21 (1.1) | ||||

| Number of Stents | ||||||||

| 0 | 137 (6.4) | 318 (5.6) | 2.082* | 0.353 | 117 (6.0) | 121 (6.2) | 6.534* | 0.038 |

| 1 | 875 (40.8) | 2344 (40.9) | 784 (39.9) | 859 (43.7) | ||||

| ≥2 | 1130 (52.8) | 3064 (53.5) | 1065 (54.2) | 986 (50.2) | ||||

| IABP | 49 (2.3) | 74 (1.3) | 10.034* | 0.002 | 32 (1.6) | 29 (1.5) | 0.150* | 0.699 |

| Medication | ||||||||

| Warfarin | 9 (0.4) | 8 (0.1) | 5.687* | 0.017 | 4 (0.2) | 6 (0.3) | 0.401* | 0.527 |

| GPI | 360 (16.8) | 936 (16.3) | 0.240* | 0.624 | 322 (16.4) | 336 (17.1) | 0.358* | 0.550 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). *χ2 values; †t values; ‡z value. PPI: Proton-pump inhibitors; PSM: Propensity score matching; PAD: Peripheral artery disease; CVD: Cerebrovascular disease; MI: Myocardial infarction; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; SAP: Systolic blood pressure; BNP: Brain natriuretic peptide; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IABP: Intra-aortic balloon pump; GPI: Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors; SD: Standard deviation.

Adenosine diphosphate-induced platelet aggregation inhibition test

ADP-induced platelet aggregation inhibition was measured by mTEG in 5042 patients per the physician's discretion. The baseline characteristics of patients were compared according to PPI use in the mTEG population, and the two groups were better matched after PSM with 1297 patients selected from each group [Table 2].

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics among patients receiving mTEG according to PPI use before and after PSM

| Parameters | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPI (n = 1368) | No PPI (n = 3674) | Statistics | P | PPI (n = 1297) | No PPI (n = 1297) | Statistics | P | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Gender (female) | 341 (24.9) | 721 (19.6) | 16.857* | <0.001 | 324 (25.0) | 260 (20.0) | 9.052* | 0.003 |

| Age (years) | 59.9 ± 10.5 | 57.6 ± 10.3 | −7.145† | <0.001 | 59.9 ± 10.6 | 59.1 ± 10.5 | −2.0368† | 0.042 |

| Past medical history | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 890 (65.1) | 2343 (63.8) | 0.746* | 0.388 | 849 (65.5) | 854 (65.8) | 0.043* | 0.839 |

| Dyslipidemia | 916 (67.0) | 2507 (68.2) | 1.453* | 0.228 | 869 (67.0) | 879 (67.8) | 0.175* | 0.675 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 409 (29.9) | 1124 (30.6) | 0.228* | 0.633 | 394 (30.4) | 388 (29.9) | 0.066* | 0.797 |

| PAD | 48 (3.5) | 94 (2.6) | 3.289* | 0.070 | 46 (3.5) | 37 (2.9) | 1.008* | 0.315 |

| Prior CVD | 187 (13.7) | 342 (9.3) | 20.187* | <0.001 | 175 (13.5) | 179 (138) | 0.052* | 0.819 |

| Prior MI | 279 (20.4) | 1035 (28.2) | 31.282* | <0.001 | 263 (20.3) | 277 (21.4) | 0.458* | 0.498 |

| Prior PCI | 352 (25.7) | 1062 (28.9) | 4.979* | 0.026 | 317 (24.4) | 335 (25.8) | 0.664* | 0.415 |

| Prior CABG | 63 (4.6) | 171 (4.7) | 0.005* | 0.941 | 61 (4.7) | 62 (4.8) | 0.009* | 0.926 |

| Admission features | ||||||||

| Acute MI | 300 (21.9) | 698 (19.0) | 5.396* | 0.020 | 267 (20.6) | 228 (17.6) | 3.797* | 0.051 |

| LVEF (%) | 62.0 ± 7.8 | 62.4 ± 7.5 | 1.607† | 0.108 | 62.2 ± 7.6 | 62.4 ± 7.5 | 0.587† | 0.557 |

| Killip class ≥2 | 19 (1.4) | 30 (0.8) | 3.393* | 0.065 | 15 (1.2) | 14 (1.1) | 0.035* | 0.852 |

| SAP (mmHg) | 126.2 ± 17.3 | 126.5 ± 16.7 | 0.641† | 0.522 | 126.3 ± 17.3 | 127.3 ± 16.9 | 1.564† | 0.118 |

| Current smoking | 783 (57.2) | 2151 (58.5) | 0.703* | 0.402 | 738 (56.9) | 749 (57.7) | 0.191* | 0.662 |

| Laboratory test | ||||||||

| BNP (pg/ml) | 648.8 (474.6–909.2) | 615.7 (480.5–843.6) | −2.030‡ | 0.042 | 646.4 (474.1–911.6) | 610.6 (480.6–842.5) | −1.832‡ | 0.067 |

| eGFR (ml/min) | 89.6 ± 15.4 | 92.2 ± 14.7 | 5.408† | <0.001 | 89.6 ± 15.4 | 90.4 ± 15.1 | 1.354† | 0.176 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 7 (4–16) | 7 (3–14) | −2.983‡ | 0.003 | 7 (4–16) | 7 (3–13) | −3.795‡ | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 140.9 ± 15.9 | 144.2 ± 14.8 | 6.553† | <0.001 | 140.9 ± 15.9 | 144.3 ± 16.0 | 5.472† | <0.001 |

| Procedural characteristics | ||||||||

| Thrombolysis | 50 (3.7) | 134 (3.6) | <0.001* | 0.990 | 49 (3.8) | 50 (3.9) | 0.011* | 0.918 |

| Syntax score | ||||||||

| 0–22 | 1188 (86.8) | 3233 (88.0) | 1.615* | 0.446 | 1129 (87.0) | 1143 (88.1) | 0.796* | 0.672 |

| 23–32 | 153 (11.2) | 383 (10.4) | 143 (11.0) | 133 (10.3) | ||||

| ≥33 | 27 (2.0) | 58 (1.6) | 25 (1.9) | 21 (1.6) | ||||

| Number of stents | ||||||||

| 0 | 80 (5.8) | 207 (5.6) | 1.055* | 0.590 | 72 (5.6) | 66 (5.1) | 0.279* | 0.870 |

| 1 | 512 (37.48) | 1433 (39.0) | 485 (37.4) | 486 (37.5) | ||||

| ≥2 | 776 (56.7) | 2034 (55.4) | 740 (57.1) | 745 (57.4) | ||||

| IABP | 29 (2.1) | 36 (1.0) | 10.181* | 0.001 | 21 (1.6) | 19 (1.5) | 0.102* | 0.750 |

| Medication | ||||||||

| Warfarin | 2 (0.1) | 6 (0.2) | 0.018* | 0.892 | 2 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 0.668* | 0.414 |

| GPI | 222 (16.2) | 604 (16.4) | 0.033* | 0.857 | 202 (15.6) | 233 (18.0) | 2.654* | 0.103 |

Data are presented as n (%), mean ± SD or median (interquartile range). *χ2 values; †t values; ‡z value. PPI: Proton-pump inhibitors; mTEG: Modified thromboelastograph; PSM: Propensity score matching; PAD: Peripheral artery disease; CVD: Cerebrovascular disease; MI: Myocardial infarction; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction; SAP: Systolic blood pressure; BNP: Brain natriuretic peptide; eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; IABP: Intra-aortic balloon pump; GPI: Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors; SD: Standard deviation; 1 mmHg=0.133 kPa.

Before PSM, the ADP-induced platelet aggregation inhibition was lower in PPI users than in non-PPI users (42.0 ± 30.9% vs. 46.4 ± 31.4%, t = 4.435, P < 0.001). A greater proportion of patients had CLR in the group that received PPIs (41.3% vs. 36.1%, χ2 = 11.420, P = 0.001). After PSM, the differences were even larger, and 30 (2.3%) non-PPI users were identified as having a CLR, whereas 528 (40.7%) PPI users were identified as having a CLR (2.3% vs. 40.7%, χ2 = 566.262, P < 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Platelet function results among patients receiving mTEG according to PPI use before and after PSM

| Variables | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPI (n = 1368) | No PPI (n = 3674) | Statistics | P | PPI (n = 1297) | No PPI (n = 1297) | Statistics | P | |

| ADP-inhibition (%) | 37.6 (15.9–64.2) | 42.2 (20.4–73.2) | −4.402† | <0.001 | 37.7 (16.1–64.9) | 43.0 (23.0–75.0) | −4.750† | <0.001 |

| ADP-inhibition <30% | 565 (41.3) | 1327 (36.1) | 11.420* | 0.001 | 528 (40.7) | 30 (2.3) | 566.261* | <0.001 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (interquartile range). *χ2 values; †z values. mTEG: Modified thromboelastograph; PSM: Propensity score matching; PPI: Proton-pump inhibitors; ADP: Adenosine diphosphate.

Clinical outcomes

Before PSM, the occurrence of MACCE between PPI users and non-PPI users in the total population showed no significant difference (12.7% vs. 12.5%, χ2 = 0.086, P = 0.769), and no differences were observed in the incidence of all-cause death (1.4% vs. 1.3%, χ2 = 0.097, P = 0.755), MI (2.4% vs. 2.0%, χ2 = 0.950, P = 0.330), unplanned TVR (9.1% vs. 8.8%, χ2 = 0.199, P = 0.655), ST (1.2% vs. 0.9%, χ2 = 1.095, P = 0.295), stroke (1.4% vs. 1.4%, χ2 = 0.084, P = 0.772), bleeding (6.6% vs. 6.5%, χ2 = 0.060, P = 0.806), BARC 3 or 5 bleeding (0.5% vs. 0.5%, χ2 = 0.095, P = 0.758), and gastrointestinal bleeding events (1.7% vs. 1.2%, χ2 = 2.272, P = 0.132). After PSM, the occurrence of MACCE (12.4% vs. 12.7%, χ2 = 0.048, P = 0.827), all-cause death (1.3% vs. 1.4%, χ2 = 0.080, P = 0.777), MI (2.4% vs. 2.4%, χ2 = 0.000, P = 0.998), unplanned TVR (8.9% vs. 9.0%, χ2 = 0.006, P = 0.937), ST (1.1% vs. 0.9%, χ2 = 0.425 P = 0.515), stroke (1.4% vs. 1.1%, χ2 = 0.721, P = 0.396), bleeding (7.0% vs. 5.9%, χ2 = 1.860, P = 0.173), and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding events (0.5% vs. 0.2%, χ2 = 2.623, P = 0.105) did not significantly differ between the two groups, and there was only a trend for an increase in gastrointestinal bleeding events in PPI users (1.8% vs. 1.2%, χ2 = 2.960, P = 0.085) [Table 4a].

Table 4a.

Clinical outcomes among all patients according to PPI use before and after PSM

| Clinical endpoint | Before PSM | After PSM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPI (n = 2142) | No PPI (n = 5726) | χ2 | P | PPI (n = 1966) | No PPI (n = 1966) | χ2 | P | |

| Primary endpoint | ||||||||

| MACCE | 273 (12.7) | 716 (12.5) | 0.086 | 0.769 | 244 (12.4) | 249 (12.7) | 0.048 | 0.827 |

| Secondary endpoint | ||||||||

| All cause death | 30 (1.4) | 75 (1.3) | 0.097 | 0.755 | 25 (1.3) | 27 (1.4) | 0.080 | 0.777 |

| MI | 51 (2.4) | 116 (2.0) | 0.950 | 0.330 | 48 (2.4) | 48 (2.4) | <0.001 | 0.998 |

| Unplanned TVR | 195 (9.1) | 504 (8.8) | 0.199 | 0.655 | 174 (8.9) | 176 (9.0) | 0.006 | 0.937 |

| Stent thrombosis | 25 (1.2) | 52 (0.9) | 1.095 | 0.295 | 21 (1.1) | 17 (0.9) | 0.425 | 0.515 |

| Stroke | 31 (1.4) | 78 (1.4) | 0.084 | 0.772 | 28 (1.4) | 22 (1.1) | 0.721 | 0.396 |

| Safety endpoint | ||||||||

| Bleeding | 142 (6.6) | 372 (6.5) | 0.060 | 0.806 | 137 (7.0) | 116 (5.9) | 1.860 | 0.173 |

| BARC 3 or 5 | 10 (0.5) | 10 (0.5) | 0.095 | 0.758 | 10 (0.5) | 4 (0.2) | 2.623 | 0.105 |

| GI bleeding | 36 (1.7) | 71 (1.2) | 2.272 | 0.132 | 36 (1.8) | 23 (1.2) | 2.960 | 0.085 |

Data are presented as n (%). PPI: Proton-pump inhibitors; PSM: Propensity score matching; MACCE: Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MI: Myocardial infarction; TVR: Target vessel revascularization; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; GI: Gastrointestinal.

After multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, there was only a trend for an increase in BARC 3 or 5 bleeding and gastrointestinal bleeding in PPI users after PSM (HR: 0.586, 95% CI: 0.341–1.009, P = 0.054), and the other endpoints showed no significant differences after multivariate adjustment, regardless of PSM, between two groups [Table 4b].

Table 4b.

Multivariate Cox proportional regression analysis among all patients according to PPI use before and after PSM

| Clinical endpoint | Before PSM | After PSM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Primary endpoint | ||||

| MACCE | 1.049 (0.854–1.289) | 0.651 | 0.970 (0.808–1.165) | 0.745 |

| Secondary endpoint | ||||

| All cause death | 0.775 (0.410–1.465) | 0.433 | 0.935 (0.534–1.634) | 0.812 |

| MI | 0.838 (0.508–1.383) | 0.490 | 0.904 (0.597–1.368) | 0.634 |

| Unplanned TVR | 1.042 (0.822–1.322) | 0.733 | 0.992 (0.798–1.233) | 0.942 |

| Stent thrombosis | 0.964 (0.451–2.064) | 0.925 | 0.736 (0.380–1.425) | 0.363 |

| Stroke | 2.171 (0.896–5.258) | 0.086 | 0.730 (0.409–1.302) | 0.286 |

| Safety endpoint | ||||

| Bleeding | 1.094 (0.821–1.458) | 0.539 | 0.841 (0.651–1.086) | 0.184 |

| BARC 3 or 5 | 0.572 (0.218–1.502) | 0.257 | 0.341 (0.103–1.132) | 0.079 |

| GI bleeding | 0.800 (0.455–1.409) | 0.440 | 0.586 (0.341–1.009) | 0.054 |

PPI: Proton-pump inhibitors; PSM: Propensity score matching; HRs: Hazard ratios; CIs: Confidence intervals; MACCE: Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; MI: Myocardial infarction; TVR: Target vessel revascularization; BARC: Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; GI: Gastrointestinal.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective observational study, we investigated the impact of concomitant administration of PPIs with DAPT therapy among patients who underwent PCI. The major strength of this study was the use of a large sample size from a single-center database with a long follow-up duration of 2 years, and we evaluated the interaction between DAPT and PPIs in both pharmacodynamic and clinical aspects. To overcome this selection bias for PPI use, PSM was implemented so that the 2 cohorts could be meaningfully compared. The study has the following notable findings.

First, approximately 27.2% of the patients were prescribed PPIs; these patients were likely to be older and female and to have increased comorbid illness, such as diabetes mellitus or cerebral vascular disease, and they were more likely to present with lower hemoglobin, lower creatinine clearance, and higher BNP. The PPI use pattern suggests that physicians were prescribing PPIs to those who were at higher baseline bleeding risk in accordance with new recommendations.[11] Interestingly, patients with prior MI were less likely to be prescribed PPIs, possibly due to concerns regarding the interaction between PPI and clopidogrel.

Second, the inhibition of platelet aggregation assessed by mTEG was significantly lower in patents with concomitant PPI use than in those without. In addition, a significant association between CLR and treatment with PPIs was observed. In 2006, Gilard et al.[4,17] first reported the competitive effect of PPIs on CYP2C19 by means of a platelet phosphorylated vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein test, which might diminish the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel. While vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein phosphorylation evaluates the platelet activation from the P2Y12 ADP receptor, mTEG uses whole blood to evaluate the clot strength and ensures a quantitative analysis of platelet function, which is more likely to mirror the platelet behavior in human blood vessels and is capable of identifying patients undergoing PCI who are at risk for ischemic events.[18,19]

Third, the combination of PPIs with DAPT might not increase the risk of MACCE at up to 2 years of follow-up. This finding is consistent with those of randomized controlled trials, which suggested no association of PPI use with increased risk of ischemic events.[20,21,22] Some retrospective analyses suggested higher incidence rates of cardiovascular events in patients taking both DAPT and PPIs.[5,6,7] The reason might be a lack of adjustment for confounding factors. A meta-analysis that included a total of 23 studies and 222,311 patients showing increased cardiovascular risks with PPIs in the absence of clopidogrel also suggested that confounding and bias were strong possibilities.[21] The PLATO trial studied 9291 patients with concomitant clopidogrel use and found that the risk of 1-year cardiovascular events was higher (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04–1.38) in patients treated with PPIs than in patients who were not treated with PPI. Similarly, this increased risk in the PPI group was also reported with the use of ticagrelor, which is a P2Y12 inhibitor that does not need biotransformation and has no effect on the CYP2C19 isoenzyme. That study also indicated that PPI use is more of a marker for higher rates of cardiovascular events.[22]

There are several limitations of this study. The use of PPIs was not selected in a randomized fashion and was determined at the discretion of the physician. The indication for PPI treatment was not captured. Although PSM was performed, potential unmeasured confounding factors remain. Different PPI types might have variable interactions with the cytochrome P450 system, which is not specified in this study. In this observational study, we did not conduct a before and after analysis, which could provide more powerful evidence on the pharmacodynamic effect of PPIs on platelet aggregation inhibition by clopidogrel. In addition, PPI use might be discontinued during the 2-year follow-up.

In conclusion, the combination of PPIs with DAPT was not associated with increased risk of MACCE in patients who underwent PCI at up to 2 years of follow-up.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81470486), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China during the 13th 5-Year Plan Period (No. 2016YFC1301301).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Peng Lyu

REFERENCES

- 1.Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Byrne RA, Collet JP, Costa F, Jeppsson A, et al. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS: The task force for dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease of the European society of cardiology (ESC) and of the European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS) Eur Heart J. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx419. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandrasekhar J, Bansilal S, Baber U, Sartori S, Aquino M, Farhan S, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors and dual antiplatelet therapy cessation on outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention: Results from the PARIS registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;89:E217–25. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26716. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Paterson JM, Hellings C, Mamdani MM. Trends in the coprescription of proton pump inhibitors with clopidogrel: An ecological analysis. CMAJ Open. 2015;3:E428–31. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140078. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20140078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, et al. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: The randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:256–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.064. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, Szmitko PE, Austin PC, Tu JV, et al. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ. 2009;180:713–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082001. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, Fihn SD, Jesse RL, Peterson ED, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009;301:937–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.261. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stockl KM, Le L, Zakharyan A, Harada AS, Solow BK, Addiego JE, et al. Risk of rehospitalization for patients using clopidogrel with a proton pump inhibitor. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:704–10. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.34. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weisz G, Smilowitz NR, Kirtane AJ, Rinaldi MJ, Parvataneni R, Xu K, et al. Proton pump inhibitors, platelet reactivity, and cardiovascular outcomes after drug-eluting stents in clopidogrel-treated patients: The ADAPT-DES study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8 doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001952. pii: e001952. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ayub A, Parkash O, Naeem B, Murtaza D, Khan AH, Jafri W, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and other disease-based factors in the recurrence of adverse cardiovascular events following percutaneous coronary angiography: A long-term cohort. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2016;35:117–22. doi: 10.1007/s12664-016-0645-0. doi: 10.1007/s12664-016-0645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gargiulo G, Costa F, Ariotti S, Biscaglia S, Campo G, Esposito G, et al. Impact of proton pump inhibitors on clinical outcomes in patients treated with a 6- or 24-month dual-antiplatelet therapy duration: Insights from the prolonging dual-antiplatelet treatment after grading stent-induced intimal hyperplasia Study trial. Am Heart J. 2016;174:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.01.015. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, Brindis RG, Fihn SD, Fleisher LA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: A Report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines: An update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention, 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery, 2012 ACC/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease, 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction, 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes, and 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 2016;134:e123–55. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000404. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: A case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: A consensus report from the bleeding academic research consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobson AR, Petley GW, Dawkins KD, Curzen N. A novel fifteen minute test for assessment of individual time-dependent clotting responses to aspirin and clopidogrel using modified thrombelastography. Platelets. 2007;18:497–505. doi: 10.1080/09537100701329162. doi: 10.1080/09537100701329162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madsen EH, Saw J, Kristensen SR, Schmidt EB, Pittendreigh C, Maurer-Spurej E, et al. Long-term aspirin and clopidogrel response evaluated by light transmission aggregometry, verifyNow, and thrombelastography in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Chem. 2010;56:839–47. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.137471. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.137471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Le Gal G, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. Influence of omeprazol on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated to aspirin. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2508–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02162.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JK, Wu CK, Juang JM, Tsai CT, Hwang JJ, Lin JL, et al. Non-carriers of reduced-function CYP2C19 alleles are most susceptible to impairment of the anti-platelet effect of clopidogrel by proton-pump inhibitors: A pilot study. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2016;32:215–22. doi: 10.6515/ACS20160201A. doi: 10.6515/ACS20160201A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang XF, Han YL, Zhang JH, Wang J, Zhang Y, Xu B, et al. Comparing of light transmittance aggregometry and modified thrombelastograph in predicting clinical outcomes in Chinese patients undergoing coronary stenting with clopidogrel. Chin Med J. 2015;128:774–9. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.152611. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.152611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vaduganathan M, Cannon CP, Cryer BL, Liu Y, Hsieh WH, Doros G, et al. Efficacy and safety of proton-pump inhibitors in high-risk cardiovascular subsets of the COGENT trial. Am J Med. 2016;129:1002–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.03.042. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwok CS, Jeevanantham V, Dawn B, Loke YK. No consistent evidence of differential cardiovascular risk amongst proton-pump inhibitors when used with clopidogrel: Meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:965–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.085. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman SG, Clare R, Pieper KS, Nicolau JC, Storey RF, Cantor WJ, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitor use on cardiovascular outcomes with clopidogrel and ticagrelor: Insights from the platelet inhibition and patient outcomes trial. Circulation. 2012;125:978–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.032912. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.032912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]