Background and Description

In June 2015, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Board of Directors commissioned the Sponsoring Institution 2025 (SI2025) project to develop a future vision for ACGME-accredited institutional sponsors of residency and fellowship programs. To accomplish this task, the ACGME Board of Directors appointed a 19-member SI2025 Task Force composed of members of the ACGME Board of Directors, senior health care executives, education leaders, Designated Institutional Officials (DIOs), residents, and representatives of the public to guide the project (table 2).

Table 2.

SI2025 Task Force Members

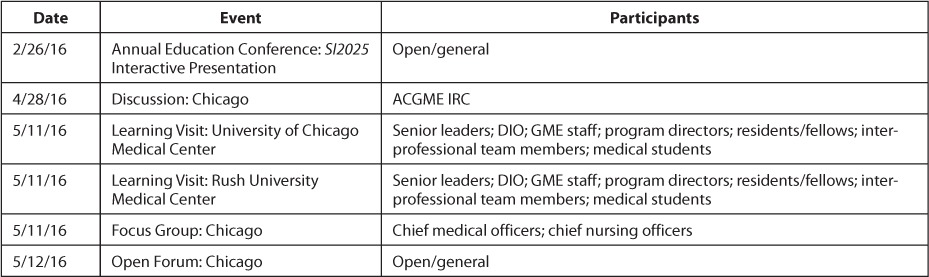

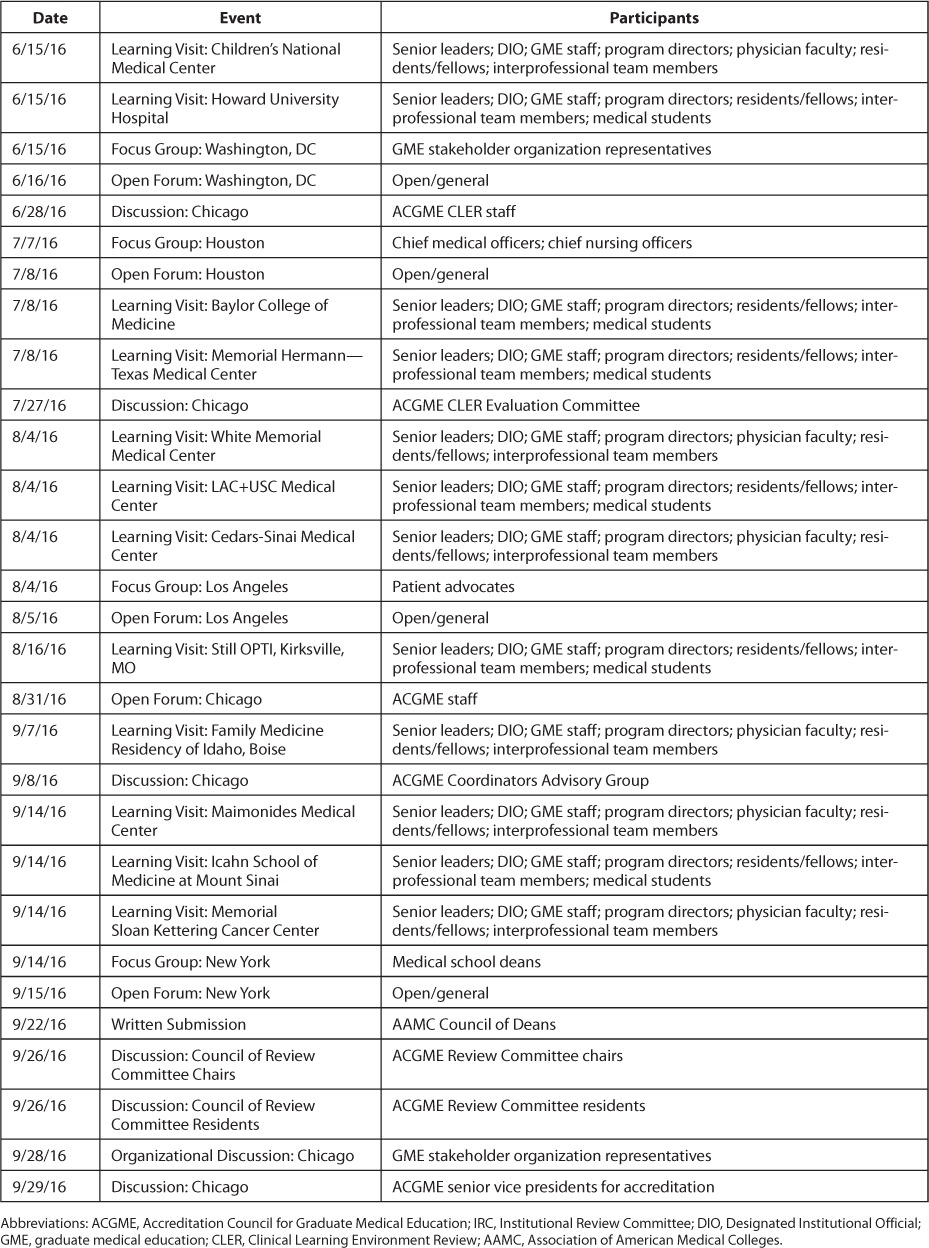

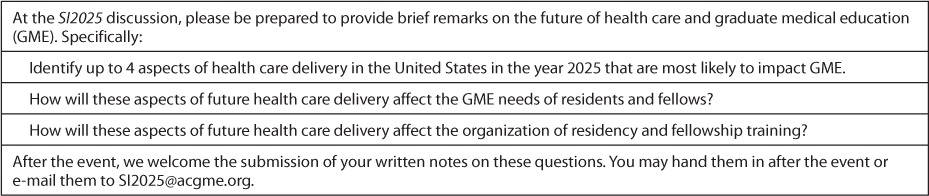

During its first meeting February 11–12, 2016, the Task Force began its work by planning a series of listening activities across the nation, to be completed over 9 months in 2016. The majority consisted of regional listening sessions, in which the Task Force led focus groups and open forum discussions, as well as “learning visits” at existing Sponsoring Institutions (SIs; table 3).1 In all, the Task Force met with 1065 diverse participants, including residents, fellows, DIOs, program directors, patient advocates, medical school deans, medical students, faculty members, interprofessional health care team members, and policy experts. All conversations were designed to engage participants in a common visioning activity: to characterize the potential structures and functions of SIs in a medical education system that will produce the physician workforce as it will have evolved in the health care system of the year 2025. Written instructions, including 3 fundamental questions, were developed to serve as the basis for all of the discussions (table 4).

Table 3.

List of SI2025 Listening Activities

Table 3.

List of SI2025 LIstening Activities (continued)

Table 4.

Advance Instructions for Participants in SI2025 Listening Activities

Listening sessions were held in Chicago, IL; Washington, DC; Houston, TX; Los Angeles, CA; Kirksville, MO; Boise, ID; and New York, NY to ensure a representative range of perspectives. Participants imagined the ways in which future aspects of the US health care system might shape their local environments, as well as graduate medical education (GME) on the national level. In these sessions, Task Force members heard from SIs that were remarkably heterogeneous in size, structure, and mission. Participants in the listening sessions drew upon their various backgrounds, including their experiences in their own SIs. The SIs that participated were themselves diverse, including publicly and privately owned entities that ranged from overseeing a single ACGME-accredited program to more than 100. Additionally, the Task Force heard from participants who were not directly involved in SIs—or, in some cases, any GME activities—but who offered their perspectives as stakeholders in health care.

The Task Force recognized that while it heard differing views of the future of health care and GME, the listening activities were designed to provide a diverse sample of individuals' experience with health care and education in the United States. Therefore, the information gathered by the Task Force is subject to unknown bias. The Task Force sought to reduce such bias by interviewing a large number of diverse individuals from a broad range of health care and GME settings.

The listening activities explored the opportunities and threats that future SIs will face in urban, suburban, and rural settings, as well as the impact of future changes to health care delivery on the various patient populations served by participating sites for GME. To complement the information gathered in the regional listening sessions, Task Force members, in collaboration with ACGME staff, received verbal and written feedback from a number of stakeholders internal and external to the ACGME.

After the conclusion of these activities, the Task Force met October 5–6, 2016, and February 16–17, 2017, to synthesize its findings and to develop a consensus view of the future context of GME. The Task Force used its findings from the field to agree on recommendations that were to be presented to the ACGME Board of Directors. This report represents a summary of the Task Force's fieldwork, its internal deliberations, and its recommendations.

§

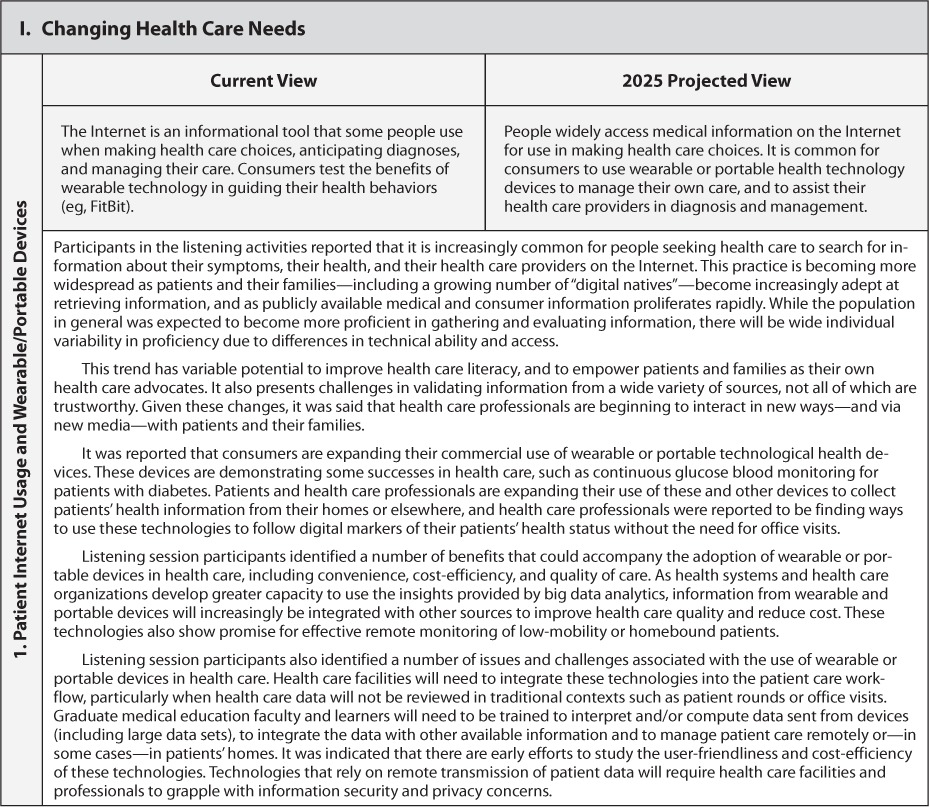

Out of the Task Force's listening activities emerged patterns of observations, perspectives, and predictions about health care and the education of health care professionals from 2016 to 2025. The “Findings” section of this document is based on these patterns as identified in the cumulative experience of the Task Force in its listening activities and in written feedback from some of the individuals interviewed. Findings were synthesized by the staff to the Task Force, and then presented to the Task Force for its review, revision, and approval. The Task Force synthesizes and interprets the findings presented in the “Summary of Findings” section of this report.

The findings were grouped into 8 themes that denote key changes envisioned by listening session participants over the next decade2:

Changing Health Care Needs

Changes in Health Care Delivery

Evolution in Health Care Systems

Evolution in the Role of the Physician

Evolution in the Role of Other Health Care Professionals

Evolution in Graduate Medical Education

Uncertainties in the Models for GME Funding; and

The Role of GME in the Continuum of Medical Education

The “Findings” section articulates a collective perspective on these themes in health care, education, and GME in 2025 by way of comparison with 2016. The Task Force agreed that the listening sessions also revealed a separate, significant set of distinct issues regarding the future of the practice of medicine. This set of findings describes attributes of the profession—and professionalism—that will be subject to conflict or competition in the future.

Each finding represents viewpoints expressed by multiple participants in the listening activities, and, as such, attempts to voice the collective wisdom of a broad community of stakeholders regarding the trends and forces affecting GME. Thus, the findings articulate neither the opinions of any single interviewee nor the individual perspectives of Task Force members or ACGME staff. As a reflection of the aggregated contributions of hundreds of individuals, the findings may or may not be consistent with other attempts to describe the future of health care and medical education.

The Task Force recognizes that 2025 is not a distant horizon. Indeed, one can already trace some early aspects of the Task Force's predictions in the present day. Nonetheless, the Task Force expects the direction and velocity of change to transform SIs in key ways over the next decade.

In its “Summary of Findings,” the Task Force identifies democratization, commoditization, and corporatization as 3 major drivers of change that appear to be guiding the future of health care, and thereby shaping the conditions to which GME will need to adapt. The Task Force recognizes that while these are not the only forces prompting change, the 3 phenomena were recognized as particularly noteworthy in the context of the summary and its recommendations. The report's “Summary of Findings” section describes the 3 forces and their potential impact on health care, the practice of medicine, and the educational needs of residents and fellows. This section also discusses the implications of a separate set of findings related to the future of the profession of medicine, and offers a means of addressing these concerns in present and future GME. The “Summary of Findings” section ends with the conclusions that form the basis for the Task Force's recommendations.

The “Recommendations” section concludes the report by describing ways in which the ACGME can prepare GME stakeholders for the future of health care and education in SIs with new structures and functions.

§

Readers are encouraged to view the components of this report as modular; that is, many sections are interrelated or self-contained, and it is not necessary to read them in a particular sequence. Some may find it useful to start with the particular findings; others may prefer to skip to the recommendations before reading the details derived from the listening activities.

Identification of Findings

Each of the SI2025 project findings reflects viewpoints expressed by multiple individuals interviewed during the SI2025 listening activities that occurred in 2016. As such, the findings represent neither the opinions of any single interviewee, nor the individual perspectives of Task Force members or Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) staff, nor the views of the ACGME. As a reflection of the collective opinions of more than 1000 individuals, these findings may or may not be consistent with other attempts to describe the future of health care and medical education. While the 52 findings are grouped in 9 thematic categories—including a discrete category of concerns for the future of the medical profession—the order of the findings is arbitrary, and many of the findings are interrelated.

Summary of Findings

The findings in the previous section represent the collective viewpoints of participants in the SI2025 listening activities, who described potential developments in health care and the education of physicians in the coming decade. The listening activities provided a wealth of information about emerging conditions and trends from which to develop a vision for Sponsoring Institutions (SIs) that is rooted in the context of projected future health care and educational environments.

At its October 2016 and February 2017 meetings, the Task Force explored the findings and a projected evolutionary path for graduate medical education (GME). The diverse perspectives of the listening session participants as well as the Task Force (in both the sessions and its deliberations) imparted a broadly informed understanding of future physicians' professional responsibilities to patients, to their colleagues, and to fellow members of their interprofessional health care teams.

To further conceptualize the expected changes to health care and GME, the Task Force returned to the broad categories of the findings related to health care and GME in 2025:

Changing Health Care Needs

Changes in Health Care Delivery

Evolution in Health Care Systems

Evolution in the Role of the Physician

Evolution in the Role of Other Health Care Professionals

Evolution in Graduate Medical Education

Uncertainties in the Models for GME Funding

The Role of GME in the Continuum of Medical Education

Democratization, Commoditization, and Corporatization of Health Care: 3 Major Forces Shaping Health Care and the 21st-Century Physician

Utilizing the 8 broad categories of findings as a basis for further discussion, the Task Force identified 3 major driving forces that appear to be shaping changes to the health care system over time:

rapid democratization;

increasing commoditization; and

advancing corporatization.

While these 3 concepts are viewed by the Task Force as major driving forces, they are not viewed as the only causes of change—nor are they mutually exclusive. However, each figured dominantly in the forecasts of the groups interviewed. The Task Force concluded that the model for GME in 2025 will need to account for the impact of these forces of change.

Democratization

“[The act of making] (something) available to all people; [the act of making] it possible for all people to understand (something).”3

The democratization of medical knowledge and patient care emerged as a major theme in the Task Force's interpretation of its findings. This phenomenon concerns the real and potential technologically enabled diffusion of information and health care services throughout health care professions, communities, and populations. This is not to imply that there will necessarily be sweeping improvements to health care access and accessibility. As noted in the Task Force's findings, health care disparities are predicted to persist in many communities due to social, economic, and geographic factors. It remains to be seen whether the force of democratization, as defined here, will be harnessed to improve health care significantly for underserved patient populations.

In the listening sessions, there was general agreement that responsibilities for diagnosis and treatment of human disease are shared among different types of health care professionals in 2016. The roles of other health care professionals, patients, families, and artificial intelligence–assisted technology in relation to medical knowledge and patient care will continue to evolve over the coming decade.

Many patients and their families will have the ability to access electronically ever more sophisticated and personalized health information. Concomitant with expanded information access will be proprietary tools (eg, smartphone applications or “apps”) that convert complex medical knowledge into user-friendly information for the purposes of (1) guiding health care decisions; (2) assisting in formulating treatment plans; (3) facilitating health care planning; and (4) enabling self-care. Participants in the listening sessions agreed that many patients and their families will have greater control over flows of detailed health information in a manner that may enhance their participation in their health care, whether in collaboration with health care professionals and teams, or independently.

In 2025, there will be continuing differential accessibility of health information by individuals and populations, as well as continuing differential proficiency in utilizing such information. Patients' proficiency in using health information will become increasingly important, as it will increasingly determine the timing and method of patients' access to care, as well as their ability to communicate electronically and/or asynchronously with their providers. Nevertheless, most patients and families will be in greater proximity—and, in general, will have greater potential access—to a large volume of detailed information related to their own health care. The expansion of access and the creation of user-friendly technological tools is expected to improve the overall health literacy of the US population over the next decade. With respect to health care in 2016, participants in listening sessions commonly reported instances in which patients enter clinical encounters armed with considerable knowledge relevant to their care, which in some cases rivals the rote knowledge of their health care providers. As a consequence of proliferating open information sources, increasing popularity of portable/wearable devices, and increasing portability of health records, it will be increasingly routine for patients and family members to engage in independent inquiries of protected or public health information in preparation for clinical encounters with their providers.

Health information that patients and their families bring to clinical encounters can frequently add value and efficiency to the provision of health care; it also can complicate communication and the delivery of appropriate care when information is incorrect, misleading, or misinterpreted. Physicians and other health care professionals will increasingly be compelled to integrate the medical knowledge of patients and their families into the health care they provide. Physicians' ability to ensure the effective use of this information—including the ability to recognize and communicate its virtues, flaws, and limitations—will become an increasingly recognized skill.

Democratization is also predicted to have a continuing impact on other health care professions and on health care delivery systems. The scope of practice associated with many health care professions is expected to widen. As a result, more health care professionals will be expected to acquire advanced medical knowledge and skills, and to assume greater responsibility and independence in their provision of health care services. Some services, which in 2016 were only available in dedicated inpatient and ambulatory health care facilities, will be readily available through retail outlets—many of which may not be part of the traditional health care sector—in 2025. Technology enhanced with artificial intelligence will offer important contributions that enhance the reach and productivity of health care teams, and will challenge traditional definitions of health care professions.

Considered together, these trends speak to substantial changes to the health care system. For patients, the major potential upside of these changes is the expansion and accessibility of health care services made possible by advanced technology, a larger workforce, and effective teamwork. So that patients and families are optimally positioned to benefit from these advantages, health care professionals will need to be able to address the complexity that may be introduced by the multiplicity of settings, providers, and technological tools involved in the care of a given patient. Physicians will frequently be required to coordinate and utilize an unprecedented volume of health information from a variety of sources. Some health care professionals who participated in the listening activities stated that they are presently challenged to keep pace with the high volume and intensity of the medical knowledge to which they are exposed, and that they expect this difficulty to increase in the coming years.

Based on its conversations, the Task Force found that medical education—and graduate medical education in particular—was not well equipped in 2016 to accommodate the progressive democratization of medical knowledge, and the enhanced interpersonal and communication skills it will require of physicians and other health care professionals. Many listening session participants expressed that health care professionals will need to acquire the knowledge and skills needed to effectively assimilate the changing (and increasingly highly informed) perspectives of patients and their families into the work done by health care teams.

Commoditization

“ . . . [A] process in which goods or services become relatively indistinguishable from competing offerings over time. Generally speaking, commoditized products within specific categories are so similar to one another that the only distinguishing feature is pricing.”4

The Task Force agreed that the findings pointed toward a general trend of commoditization in health care, wherein health-related goods or services become so commonplace that patients and their families (as health care consumers) make choices by price, and not by the perceived quality of a provider's health care services (ie, the “brand”). This driving force is enabled by standardization and automation in health care.

Participants in the listening sessions reported that the rapid standardization of health care services will play a determinative role in how patients use the health system of 2025. By dictating the form and substance of many health care transactions, standardization will facilitate the expansion of certain health care services into new retail settings; it will formalize the respective roles of health care team members in new ways; and it will utilize technology to automate and/or guide portions of care processes. As a result, there will be fewer perceived differences in the quality of health care delivered by different providers or in different locations.

In 2016, commoditization can be observed in the delivery of certain common health care services, such as those related to cataract removal. Some health care consumers increasingly seek routine health care services (eg, immunizations) in pharmacies, “big-box” stores, other retailers, or at home. It is anticipated that over the next decade, the number and types of organizations offering these types of services will increase, and a larger and more complex range of services will be provided in nontraditional settings such as ambulatory care facilities, retail chain stores, community centers, and patients' homes.

While many examples of commoditization concern primary care services, the listening sessions also indicated commoditization of services that involve subspecialty care and/or hospitalization. Over the coming decade, for example, payment models will likely feature increasing bundling of services related to a particular health care intervention (eg, joint replacement), which will potentially encourage the provision of health care services in nontraditional and/or lower-cost settings.

Several listening session participants projected that with the expansion of some health care services into new settings, it is likely that the increasing standardization of care will provide new opportunities for health care professionals to provide some services without the direct or indirect supervision of a physician. It was projected that there will continue to be a need for ongoing oversight of care provided by health care team members, and that physicians and other health care team leaders will need to apply critical thinking skills to prevent, identify, and resolve errors in health care environments in which care is increasingly standardized and/or automated.

In the listening sessions, participants offered various perspectives on the future of health care finance, but many of their perspectives shared a common assumption: that health care consumers will assume a greater share of health care costs due to higher health insurance premiums, deductibles, copayments, and/or coverage restrictions. In the emerging health care system, consumers who are facing increasing health care expenses will weigh cost heavily when making health care decisions, thereby reinforcing patients' tendencies to make health care decisions based primarily on cost. Thus, market conditions and consumer decisions are likely to have a role in advancing the commoditization of health care.

In summary, the Task Force heard in its listening activities that commoditization will shape health care delivery in 2025 in a manner that expands health care into new settings; emphasizes the need for highly coordinated, team-based health care; uses technology to support clinical decision-making; and requires health care professionals to optimize systems to ensure patient safety while containing health care costs. The future GME system will need to prepare physicians whose sense of professionalism has evolved in relation to these dramatic changes.

Corporatization

“To subject to corporate ownership or control.”5

Since as early as the 1980s,6 it has been observed that health care in the United States increasingly embraces a corporate model. In previous decades, the corporatization of health care concerned the privatization of hospitals and the influence of national and multinational corporate interests in the health care marketplace. From 2016 to 2025, the corporatization of health care will be manifest in the ongoing consolidation of health care services and facilities under the management of large and complex health care systems.

During the listening sessions, the Task Force heard a strong signal that the practice of medicine—and, therefore, physician education—needs to adapt to keep pace with accelerating corporatization. It was apparent in the Task Force's conversations (and supported by data external to SI2025) that the practice of medicine is rapidly moving away from individual and group physician practices affiliated with hospitals, and toward large corporate systems of ownership that span inpatient and outpatient care settings. Listening session participants thought that corporatization is already altering the practice of medicine substantially; and also that the medical education system has not adequately responded to the changes.

In 2016, graduating residents, fellows, and other learners in the health care professions are transitioning from their educational programs into salaried positions in large health systems. Through mergers, acquisitions, and the creation of new facilities, many health systems are expanding their geographic coverage to serve regions of the country, to improve the stability of revenue streams, to manage cost increases, and to spread fixed costs over a larger base. It is expected that in 2025, almost all newly graduated residents and fellows will enter practice under the employment of large corporate systems. The Task Force expressed concern that without changes to the model for GME, it cannot be ensured that they will acquire skills needed to manage patient care optimally in these environments.

There is a perception that the anticipated rise of large health systems will require complex distribution and coordination of patient care responsibilities among members of health care teams, including physicians. Many physicians will be expected to be proficient in supervising and/or coordinating care within large systems. Most physicians will be expected to use clinical data for the purpose of quality improvement. While their specific roles will vary, physicians will generally be expected to perform effectively in teams and to contribute to achieving organizational goals related to operational performance and patient care.

It was observed in the listening sessions that populations in rural and urban areas of the United States are unlikely to be served fully by corporate health systems, particularly when business interests are not aligned with the economic realities of providing health care in a manner that meets these populations' health care needs. Physicians in 2025 should be prepared to address ongoing disparities in health care, including those that are created or reinforced by corporatized health care.

Teamwork, team management, organizational development, project management, data management, and leadership development—some of which are already enshrined in the ACGME competencies of practice-based learning and improvement and systems-based practice—are among the skills complex organizations will expect from physicians in their employ. The Task Force found that residents and fellows will require substantial educational experience in these and other areas to prepare them to succeed in their future practice environments.

By changing professional expectations, corporatization may challenge traditional definitions of professionalism in medicine. Rapidly growing health care corporations that engage in GME are likely to attempt to retain graduates of their residency and fellowship programs as practicing physicians, and therefore are likely to make efforts to instill professional values that are associated with a highly skilled and productive workforce. Some listening session participants expressed apprehension over the corporatization of GME and its potential for conflict with traditional views of physician autonomy and leadership in the future. There was significant concern that corporate priorities will threaten some important concerns of the medical profession such as engaging in public service and meeting community needs. To many, it was not apparent that physicians will be able to advocate for their patients effectively within large corporate structures.

Concern for Preserving Professional Attributes and Other Aspects of the Profession of Medicine

In its listening activities, the Task Force heard a number of concerns from participants about how the profession of medicine will be defined in 2025. Many of these concerns related to humanistic and altruistic aspects of physicians' sense of professionalism; others related to the definition of the profession in relation to patients, other health care professions and professionals, and the health system. All of the concerns intersect in some way with physicians' sense of professionalism, and/or in the joy derived from the fulfillment of physicians' professional roles. The concerns are summarized in the findings as follows:

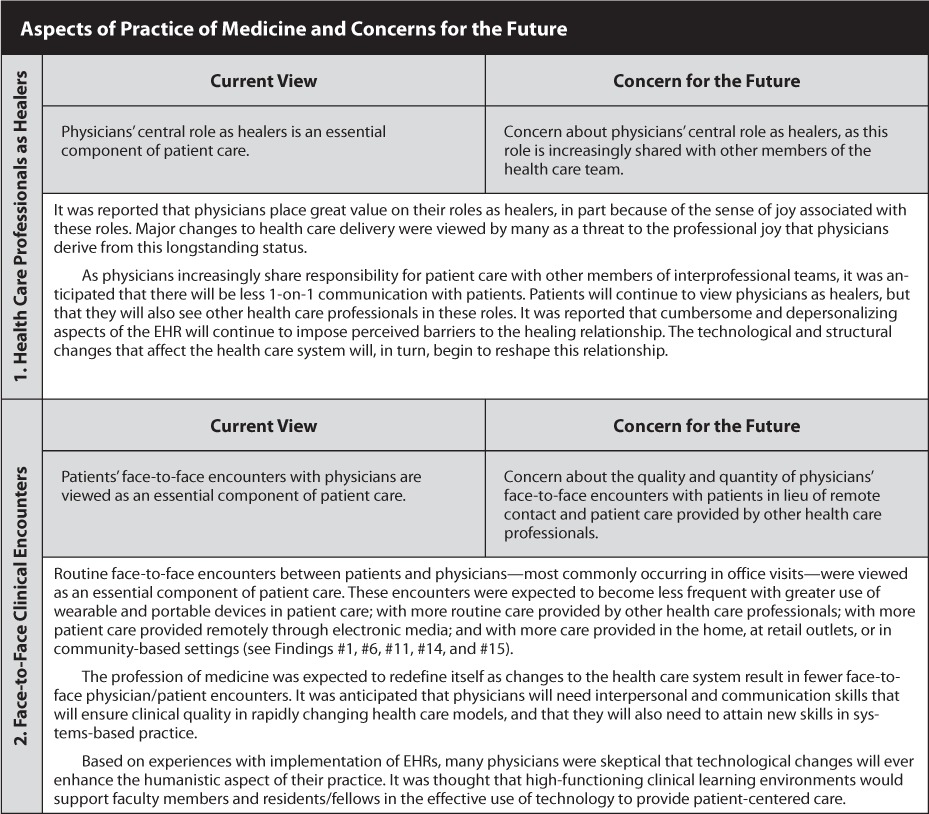

Health Care Professionals as Healers

Face-to-Face Clinical Encounters

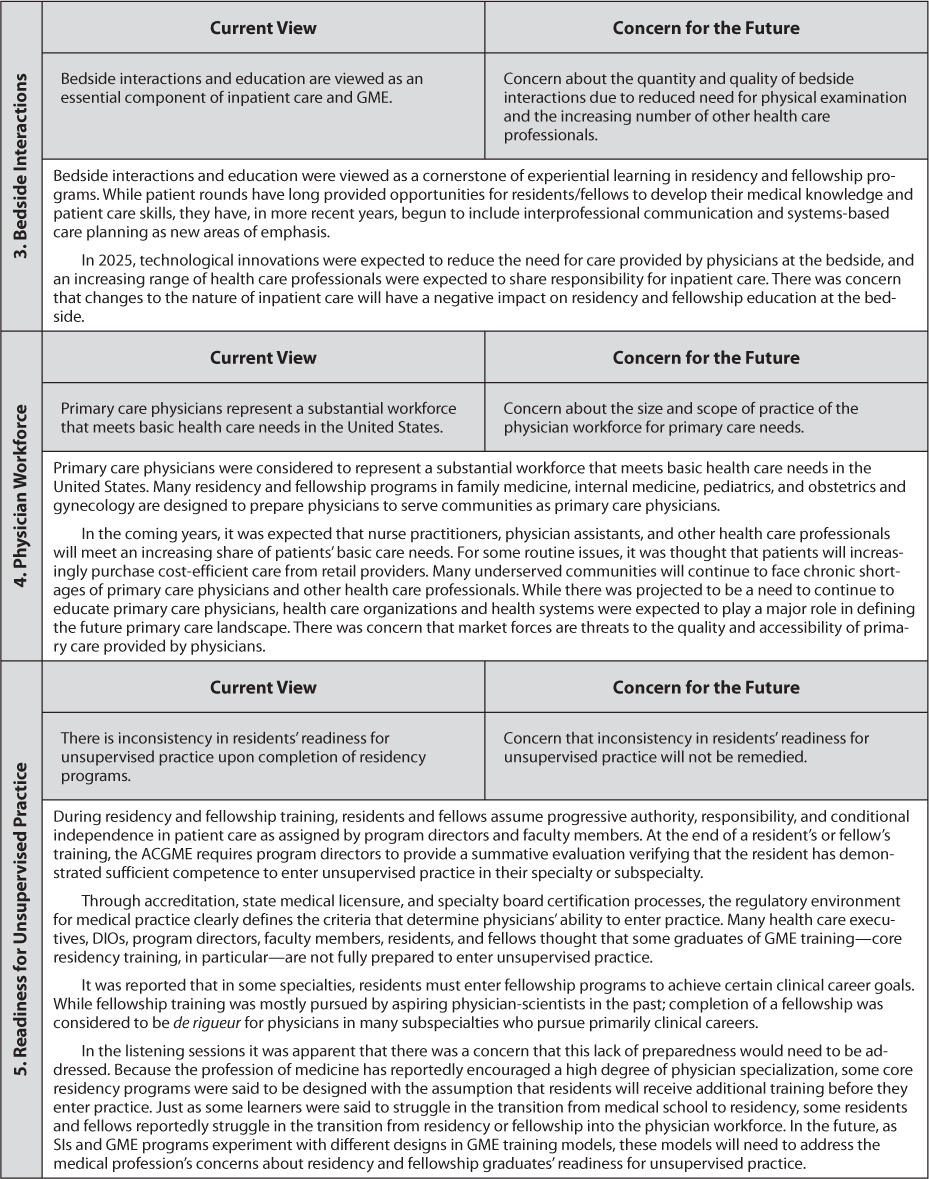

Bedside Interactions

Physician Workforce

Readiness for Unsupervised Practice

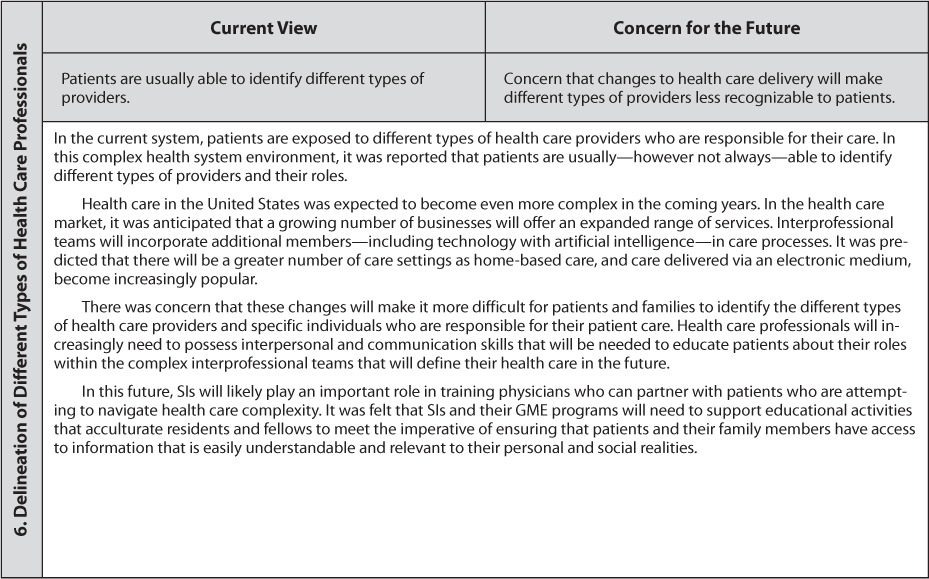

Delineation of Different Types of Health Care Professionals

Many listening session participants expressed their desire to retain positive aspects of health care and education that are perceived to be under threat by changing expectations imposed on GME by the evolving health care environment. A number of participants identified tension or conflict between attributes of the medical profession and some emerging health care trends.

Reflecting on these concerns, the Task Force concluded that in order for the profession of medicine to retain qualities and values regarded to be essential, it will be necessary to promote the following physician attributes:

▪ healers who are able to make effective use of technology and information systems to enhance their healing relationship with patients;

▪servant-leaders who collaborate with others and prioritize the needs of others in decision-making;

▪advocates who promote patient-centered care, who meet the needs of the populations they serve, who recognize and address social determinants of health, and who recognize and address disparities in health care; and

▪team members who work and communicate with health care professionals toward effective coordination of patient care.

Based on the Task Force's conversations, these attributes may be central concepts of professionalism for physicians functioning in the health care system of 2025. The meta-forces of democratization, commoditization, and corporatization have the potential to facilitate or impede the development of these physician attributes. Many listening session participants felt that the profession of medicine should advance these qualities through the educational and clinical systems overseen by SIs.

Conclusions

While the 3 driving forces of democratization, commoditization, and corporatization do not operate exclusively in the health care sector, the Task Force isolated their predicted likely impact on particular aspects of health care and the education of health care professionals in 2025.7 The Task Force also considered the attributes of professionalism that will characterize physicians in this future state. It was apparent from the findings that these and other forces would strongly influence the roles of future SIs.

In the GME system of 2025, some aspects of academic medicine—such as scientific discovery and technical innovation—are expected to follow a historical model with relatively little disruption; other aspects of physicians' professional formation—such as those described above—will need to transform.

With the aim of summarizing the information gathered and synthesizing it into a framework for the future conditions of GME, the Task Force drew the following conclusions from the SI2025 findings:

The evolution of health care will increase in complexity and pace during the next decade due to driving forces such as democratization, commoditization, and corporatization, as demonstrated in the findings of the SI2025 listening sessions.

This evolution illustrates a need to better align the resources of GME (ie, residents/fellows, program directors, faculty, GME leadership, and educational infrastructure) with efforts to improve health care.

The GME community should play constructive roles in the profession of medicine's adaptation to the rapidly evolving US health care environment.

The talent and creativity exhibited by the residents, fellows, and medical students who participated in the listening sessions are inspiring. Clinical learning environments should incorporate and recognize learners' skills and abilities in efforts to address clinical and educational challenges.

The insights and findings of the SI2025 project point to an emerging essential role for the institutional sponsor of GME (ie, ACGME-accredited SIs) to coordinate, facilitate, and lead GME changes that are consistent with the evolution of health care and the health of the US population over the next decade.

Recommendations

The Task Force makes the following recommendations based on (1) its experience of listening to a large number of stakeholders across the United States, and (2) its deliberations concerning the listening session findings and their implications for graduate medical education (GME)—and more specifically, for the role of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in accrediting Sponsoring Institutions (Sis) in the United States. This section fulfills the ACGME Board of Directors' charge to the Task Force to make recommendations concerning the future direction of ACGME institutional accreditation.

The recommendations reflect the conclusions of the “Summary of Findings” section of this report, as well as the following considerations:

▪ ACGME has been accrediting SIs of GME since 1992 and will likely continue this function.

▪ ACGME-accredited SIs serve an important role in ensuring the quality of GME.

▪ ACGME's future must be defined by the value it provides for patients, physicians, and clinical learning environments.

ACGME-Accredited Sponsoring Institutions of Today

Currently, the primary responsibilities of ACGME-accredited SIs are (1) to provide an oversight and administrative structure for ACGME-accredited residency/fellowship programs; (2) to ensure appropriate educational and clinical resources; (3) to manage the appointment of residents/fellows; (4) to maintain the quality of residents'/fellows' educational experiences and environment; and (5) to address the well-being of residents/fellows and faculty members. Key activities of present-day SIs include managing a variety of issues related to residents'/fellows' appointment to their programs; supporting the functions of the Designated Institutional Official (DIO), Graduate Medical Education Committee (GMEC), and, in most cases, a GME office; creating and maintaining appropriate communication mechanisms for GME stakeholders; and oversight efforts related to the ACGME Institutional and the Common and Specialty-Specific Program Requirements. The SI is accountable for communications with external organizations on its own behalf and that of its ACGME-accredited programs. Many SIs also assist in the administration of unaccredited residencies/fellowships, and of ACGME-accredited programs that are based in other SIs, but which assign residents/fellows for external educational experiences (ie, rotations).

In many of today's SIs, institutionally led educational activities include orientation events for new residents/fellows and ongoing educational activities as required by law or policy. In most SIs, day-to-day resident/fellow education is primarily designed and overseen by the leadership of the residents'/fellows' respective programs. SIs oversee education in their programs to ensure their compliance with ACGME Common and Specialty-Specific Program Requirements. SIs vary in the extent to which their GME leaders communicate with executive leadership of sites that participate in their GME programs.

ACGME-Accredited Sponsoring Institutions of 2025

The Task Force concludes that SIs in the year 2025 will need to have evolved into more complex entities. Sponsoring Institutions will have retained many—if not all—of the administrative and educational responsibilities detailed above. They will also have become responsible for at least 2 additional functions:

-

SIs will have begun to offer enhanced inter- and multidisciplinary educational programming and experiences for residents, fellows, and faculty that support the development of physicians in their professional roles.

SIs in 2025 will need to have developed enhanced educational experiences and programming to promote the development of skills and behaviors common to physicians across specialties. Based on input from the listening sessions, topics for such education should include, at a minimum: the use of electronic health records in decision support and management; engagement in health systems performance (eg, patient safety, quality improvement, and high-value care); professionalism and leadership skills; and interdisciplinary and interprofessional team-based performance skills and behaviors.

-

Graduate medical education leadership of SIs will have assumed increasing accountability for the value of GME. Graduate medical education leaders will have become successful in coordinating SIs' GME efforts with tactical or strategic organizational goals, in coordination with executive leaders of participating sites for GME.

The Task Force defines the value of GME as the contribution made to the improvement of health care as the result of educating residents/fellows. Not all of this value correlates with a monetary equivalent. While some types of value are undoubtedly financial, SIs' residency/fellowship programs may add value by contributing to an organizational mission in a way that does not directly produce savings or revenue.

To enhance the value of GME, SIs will need GME leaders who can engage the talents and enhance the skills of residents, fellows, and faculty in improving health care. These leaders will need to be able to demonstrate the added value of GME to the executive leadership and governance of its clinical partners. Leaders of SIs will increasingly need to collaborate with GME stakeholders (eg, quality and safety officers, departmental and program leadership, residents and fellows) to design enhanced educational experiences that provide value to the clinical enterprise. GME leaders will be responsible for ensuring the contribution of GME to health care at participating sites.

The Task Force recommends that the ACGME should guide the necessary evolution of ACGME-accredited SIs that will able to fulfill additional functions in 2025 as described above. In doing so, the ACGME should focus on 3 approaches:

Accreditation: The ACGME can introduce revisions to its Institutional Requirements to bring about desired changes to SIs. While changes to accreditation requirements can be very effective in producing limited and/or focused changes, the needs of the future SI are not entirely known. Using accreditation as the primary mechanism for driving change could limit SIs in developing innovative, creative methods for fulfilling their emerging responsibilities, and could create resistance from SIs facing other challenges in the broader regulatory environment.

Enhanced Recognition: The ACGME can offer enhanced recognition to SIs for their efforts to enhance education or add value to GME. Enhanced recognition could be conferred for reaching objective targets associated with progress toward meeting the responsibilities of a future-oriented SI. This approach could accelerate change without imposing additional requirements.

Education: ACGME educational programming can provide valuable assistance to SIs as they evolve into their future state. Changes made through education alone would depend on the motivation of SIs and the quality of the educational programming. This approach offers the most flexibility, and also draws upon the expertise and leadership of the GME community.

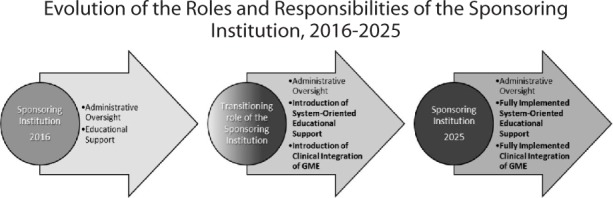

The Task Force recognizes that the projected evolution of the SI will unfold over several years, and will require a series of steps to achieve widespread and sustainable change (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Based on the results of the SI2025 project, the Task Force affirms that the ACGME should support SIs in training physicians who will be prepared to meet the needs of patients and their families in 2025. Therefore, the Task Force makes the following recommendations:

Recommendation I

The ACGME should follow a 3-step, 8-year process to revise the Institutional Requirements. The ACGME should introduce and develop standards for SIs that are consistent with the future state envisioned in the findings of SI2025.

It is recommended that the 2017–2018 revisions to the Institutional Requirements incorporate the evolution of the clinical learning environment that is represented in the revised Common Program Requirements.

In 2020, the Institutional Requirements should be revised to include expectations for robust systems-based educational support and for some strategic integration of GME and clinical learning environments.

In 2024, the Institutional Requirements should be revised to include expectations for high-performing, fully implemented educational programs around systems-based practice, and for complete strategic integration of GME within its clinical learning environments.

Recommendation II

The ACGME should develop and implement a new initiative designed to recognize SIs that are complying with Institutional Requirements while also leading in the areas of enhanced, systems-based educational support and integration of GME within clinical learning environments.

The knowledge gained from this initiative should be used in revising the Institutional Requirements, as outlined in Recommendation I. It should also be used to drive GME performance improvement by highlighting local, community-based innovation as a driver of excellence in patient care. This initiative will need to demonstrate value to SIs as well as their participating sites. If possible, this initiative should be developed in collaboration with organizations that advance health care quality.

Recommendation III

The ACGME should promote the development and implementation of educational programs that develop the skills of GME and health care leaders, faculty, residents, and fellows. These programs should emphasize activities that prepare participants to contribute effectively to the future health care system.

These educational programs should support: (1) the preparation of physicians to practice in complex health care systems; (2) an understanding of the ways by which executive leadership and their governance effect change in these complex health systems; and (3) innovation in GME that is interdisciplinary and interprofessional. If possible, this initiative should be developed in collaboration with organizations that advance health care quality.

Recommendation IV

The ACGME should develop a mechanism to continually evaluate the health care environment to ensure close alignment of ACGME expectations for SIs with the rapidly changing health care system and societal health care needs.

Continual surveillance would provide ACGME with the information needed for ongoing improvement in institutional accreditation. This recommendation provides opportunities for the ACGME to engage GME stakeholders on an ongoing basis, and to partner with other organizations to improve health care and education.

Summary

These recommendations describe a model for institutional accreditation that seeks to:

▪ ensure appropriate minimum requirements for SIs in the year 2025;

▪ support SIs in creating robust, future-oriented educational programming and experiences;

▪ create a pathway for the development of SIs that will allow them to oversee and support the education of 21st-century physicians; and

▪ provide flexibility to adjust the model in response to unpredicted changes.

This approach will prepare SIs to train a physician workforce that will succeed in their subsequent unsupervised practice, and to take a leading role in improving health care and population health in the United States.

Footnotes

1None of the information gathered in SI2025 listening activities was used in ACGME accreditation processes.

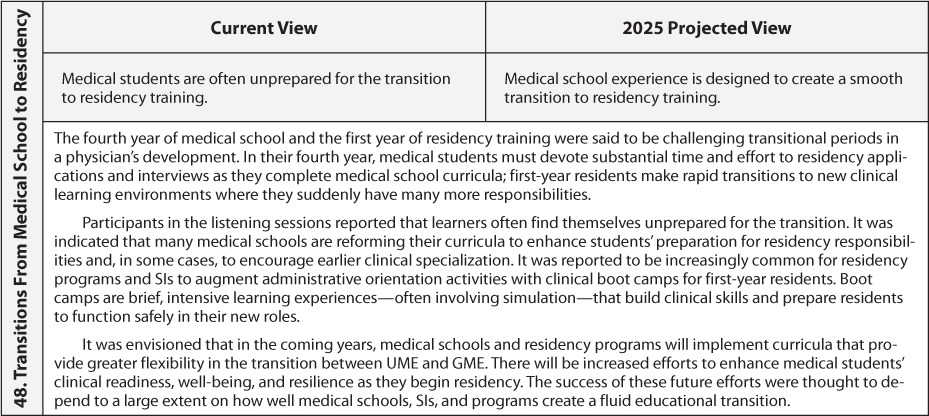

2 An additional set of Task Force observations—“Aspects of 2016 Practice of Medicine and Concerns for the Future”—differs from the findings, in that it does not, strictly speaking, address conditions of health care and graduate medical education in 2025. Rather, this section describes important concerns about the future of the profession, and about how professionalism will be defined over the next decade.

3 Merriam-Webster. “Democratize.” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/democratize. Accessed October 24, 2017.

4Investopedia LLC. “Commoditize.” http://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/commoditize.asp. Accessed October 24, 2017.

5 Merriam-Webster “Corporatize.” https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/corporatize. Accessed October 24, 2017.

6 McKinlay JB, Stoeckle JD. Corporatization and the social transformation of doctoring. Int J Health Serv. 1988;18(2):191–205.

7 The Task Force identified the 3 forces as the primary drivers of change in graduate medical education from 2016 to 2025. Numerous other phenomena will have substantial impacts on the future of graduate medical education, as noted in the “Findings.”