Abstract

Cationic antimicrobial peptides (CAMPs), such as polymyxins, are used as a last-line defense in treatment of many bacterial infections. However, some bacteria have developed resistance mechanisms to survive these compounds. Current pandemic O1 Vibrio cholerae biotype El Tor is resistant to polymyxins, whereas a previous pandemic strain of the biotype Classical is polymyxin-sensitive. The almEFG operon found in El Tor V. cholerae confers >100-fold resistance to antimicrobial peptides through aminoacylation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), expected to decrease the negatively charged surface of the V. cholerae outer membrane. This Gram-negative system bears striking resemblance to a related Gram-positive cell-wall remodeling strategy that also promotes CAMP resistance. Mutants defective in AlmEF-dependent LPS modification exhibit reduced fitness in vivo. Here, we present investigation of AlmG, the hitherto uncharacterized member of the AlmEFG pathway. Evidence for AlmG glycyl to lipid substrate transferase activity is demonstrated in vivo by heterologous expression of V. cholerae pathway enzymes in a specially engineered Escherichia coli strain. Development of a minimal keto-deoxyoctulosonate (Kdo)-lipid A domain in E. coli was necessary to facilitate chemical structure analysis and to produce a mimetic Kdo-lipid A domain AlmG substrate to that synthesized by V. cholerae. Our biochemical studies support a uniquely nuanced pathway of Gram-negative CAMPs resistance and provide a more detailed description of an enzyme of the pharmacologically relevant lysophosphospholipid acyltransferase (LPLAT) superfamily.

Keywords: aminoacyltransferase, bacterial membrane, bacterial pathogenesis, LABLAT, LPLAT, lipopolysaccharide, Vibrio cholera, antimicrobial peptide (AMP), antibiotic resistance, acyltransferase

Introduction

The lysophospholipid acyltransferase (LPLAT)2 superfamily is a massive collection of enzymes present throughout all domains of life, where most genomes encode multiple superfamily homologs. Foundational LPLAT enzymes generally catalyze transfer of acyl groups from donor molecules, like carrier proteins or coenzyme A, onto acceptor lipids, such as lyso-glycerophospholipids or lipid A, or glycerophospholipid precursors, such as dihydroxyacetonephosphate or glycerophosphate. Research on bacterial LPLATs has not only shown their impact on the chemical composition of membrane lipids, and how variation in composition contributes to organismal fitness, but has also demonstrated how specific environmental factors trigger remodeling of bacterial membranes through sensory pathways that coordinate regulation of LPLAT activities (1–3).

Lipid A biosynthesis late acyltransferases (LABLAT) compose a characteristic subgroup within the LPLAT superfamily and participate in secondary acylation of bacterial keto-deoxyoctulosonate (Kdo)-lipid A domains during the final steps of canonical biosynthesis. Biochemical characterization of LABLAT members was first performed with source material from Escherichia coli, where secondary acyltransferases esterify acyl groups to primary hydroxylacyl chains of nascently synthesized Kdo2-lipid IVA (4, 5). In E. coli these activities are encoded by lpxL or lpxM (Fig. 1A), which transfer lauroyl (C12:0, 12 carbons) or myristoyl (C14:0, 14 carbons) fatty acids from acyl carrier proteins to hydroxyacyl fatty acids at the 2′- and 3′-positions of the Kdo-lipid A di-glucosamine backbone, respectively (4, 5). Subsequent investigations of LABLAT homologs across numerous bacterial species show nuanced heterogeneity in acyl chain selectivity and variance in positional specificity in hydrocarbon transfer to target substrates (6–9).

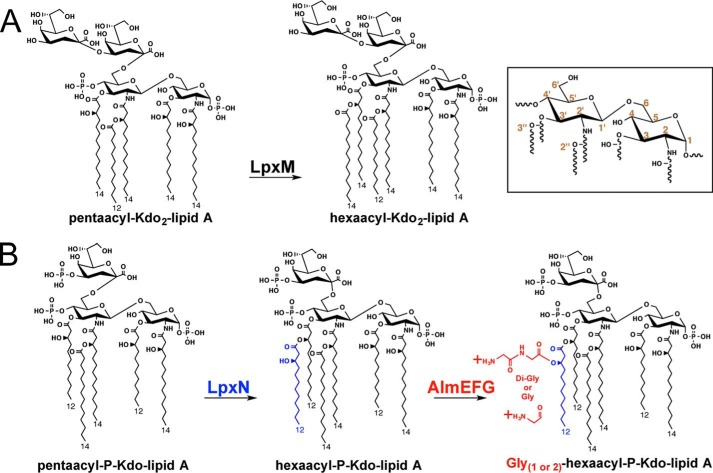

Figure 1.

Multiple differences in the predominant chemical structures of Kdo-lipid A domains of E. coli K-12 compared with V. cholerae biotype El Tor. Inset provides numeric classification legend for describing acyl chain position along the glucosamine disaccharide. A, E. coli possess a bi-functional Kdo transferase that transfers individual Kdo sugars to lipid IVA and Kdo-lipid IVA successively. The lipid A secondary acyltransferase LpxL and then LpxM acyltransferases produce the predominantly observed hexaacyl-Kdo2-lipid A. B, V. cholerae Kdo-lipid A domains contain hydroxylaurate chains at 3- and 3′-positions. V. cholerae expresses a monofunctional KdtA that transfers a single Kdo residue to lipid IVA and a Kdo kinase that phosphorylates Kdo-lipid IVA. V. cholerae LpxL (Vc0213) transfers a myristate (C14:0) to the 2′-position hydroxylacyl chain of the glucosamine disaccharide. LpxN (Vc0212) transfers a 3-hydroxylaurate (3-OH C12:0; blue) to the 3′-position hydroxyacyl chain to generate hexaacyl-monophosphoryl-Kdo lipid A. AlmEFG adds glycine to the 3-hydroxylaurate of hexaacyl-monophosphoryl-Kdo lipid A. Glycine and diglycine modified hexaacyl-monophosphoryl-Kdo-lipid A are highly abundant in V. cholerae biotype El Tor under standard growth conditions.

LpxN is a recently described member of the LABLAT subgroup found in the human intestinal pathogen Vibrio cholerae (Fig. 1B), which annually infects millions of people around the world, especially in Southeast Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa (10, 11). Subsequent elucidation of LpxN activity showed it transfers a 3-hydroxylaurate residue to the primary 3′-hydroxylacyl chain of V. cholerae Kdo-lipid A domains (10). LpxN deletion mutants are sensitive to polymyxin B by >100-fold relative to wild type, current pandemic V. cholerae El Tor strains (10, 11). Inactivating mutants of distantly related LABLAT members from other organisms such as Klebsiella, Escherichia, Salmonella, and Acinetobacter also display sensitivity to CAMPs (9, 10, 12, 13) but not to the same degree as LpxN inactivation, which produces an order of magnitude more sensitivity to CAMPS (10, 11).

Mass spectrometric structural analysis of Kdo-lipid A domains isolated from V. cholerae biotype El Tor showed evidence for attachment of glycine or diglycine residues to the 3-hydroxyl of LpxN-transferred 3-hydroxylauryl groups (14). A multiprotein pathway, AlmEFG (Fig. 1B), was identified as responsible for the observed Kdo-lipid A glycine modification. Discovery of the AlmEFG pathway resolved a decades long mystery in clinical surveillance of V. cholerae as to why current pandemic biotype El Tor is resistant to polymyxin B, but the previous pandemic biotype “Classical” is sensitive. Classical strains lack a functional AlmEFG pathway, due to an inactivating mutation in AlmF (Vc1578; Fig. 1), later determined to be a glycine-carrier protein (15). Further biochemical characterization of AlmE (Vc1579), a dual aminoacyl-adenyltransferase/carrier protein ligase, implicated its role in transfer of an activated glycine to the phosphopantetheinyl prosthetic group of holo-AlmF carrier molecules (15). AlmEFG glycine modification to V. cholerae surface lipids revealed an emergent paradigm in membrane remodeling between Gram-negatives and Gram-positives with respect to CAMPs defense, as Gram-positives similarly decorate their surface teichoic acids with aminoacyl groups (14–16).

In this report the biochemistry of a distant LABLAT homolog, AlmG (Vc1577), is explored, providing evidence to support its hitherto putative role as a glycyltransferase in the AlmEFG pathway. Evidence for AlmG glycyl to lipid substrate transferase activity is demonstrated in vivo by heterologous expression of V. cholerae pathway enzymes in a specially engineered E. coli strain. Development of a minimal Kdo-lipid A domain in E. coli was necessary to facilitate chemical structure analysis and to produce a mimetic Kdo-lipid A domain AlmG substrate to that synthesized by V. cholerae. With this report AlmG becomes the only characterized aminoacyl transferase in the LPLAT superfamily. Further mutational analysis of putative catalytic residues reveals an active site unique to AlmG, which indicates a chemical mechanism that may be distinct from other characterized LABLAT subgroups and LPLAT superfamily members.

Results

Rationale, genetic construction, and LPS analysis of E. coli that produce simplified Kdo-lipid A domains

It remains possible that AlmG might require idiosyncratic features of the Kdo-lipid A domain biosynthesized by V. cholerae, similar to the specific requirement of V. cholerae LpxL for a phosphorylated Kdo domain (17). To better investigate AlmG activity and any potential substrate requirements, we sought to engineer an E. coli strain that produced a simplified Kdo-lipid A domain containing a 3″-hydroxylauryl. This would allow definition of the minimum factors for Kdo-lipid A glycine modification in a non-native organism.

E. coli strain design started with deletion of the LpxM acyltransferase to produce a penta-acylated Kdo-lipid A domain, lacking the secondary myristoyl acyl chain. Our previous study showed V. cholerae LpxN can replace LpxM in E. coli (10), with a final lipid A product that contains a 3-hydroxylauoryl group at the 3″-position (Fig. 1B) (14), the substrate hydroxyl group for putative AlmG glycine transfer. Deletion of lpxT was also performed, which encodes a phosphotransferase dispensable for growth in E. coli (18), not found in V. cholerae, and complicates downstream analysis of 32P-radiolabeled lipids by thin-layer chromatography (19). Finally, mutants in the Kdo2-lipid A heptosyltransferase pathway of E. coli (supplemental Fig. S2), responsible for initiating LPS inner core oligosaccharide synthesis, were also targeted. Others have successfully disrupted the rfaDFC (also known as waaDFC) operon in E. coli with no apparent effect on viability (20, 21). Our rationale for the heptosyltransferase disruption step was multifold: (i) produce a minimal Kdo-lipid A domain; (ii) slow core-lipid A transport across the inner membrane to potentially increase efficiency of the predicted cytoplasmic glycine modification; and (iii) simplify downstream isolation of Kdo-lipid A material.

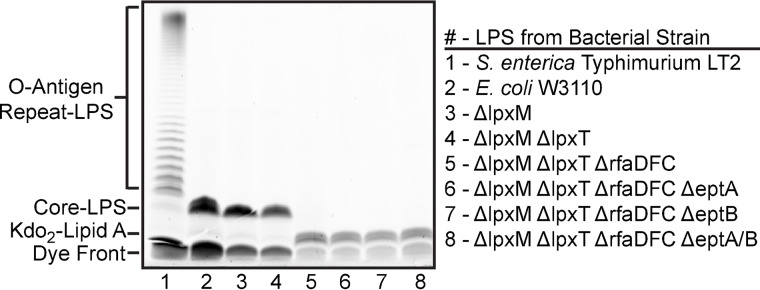

In the E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT mutant, we were able to cleanly delete the entire rfaDFC operon (supplemental Fig. S2) using a recombineering approach (22). Verification that core-oligosaccharide truncated Kdo2-lipid A species are produced by the engineered E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT ΔrfaDFC was assessed by ProQ Emerald detection of isolated LPS separated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2). Consistent with disruption of the heptosyl transfer reactions, and core-oligosaccharide synthesis, a smaller molecular weight species was readily apparent in isolated LPS from the ΔrfaDFC mutant versus parental strain E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT (Fig. 2; compare lanes 5 versus 4). For reasons discussed below, further mutations to E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT ΔrfaDFC were performed, and they maintained the core-oligosaccharide truncated phenotype (Fig. 2, lanes 6–8).

Figure 2.

Electrophoretic separation and ProQ Emerald dye visualization of isolated LPS. Numbered lanes below the LPS gel correspond to strains listed on the right. S. enterica serovar typhimurium LT2 is included as a control (lane 1), to show a typical O-antigen repeat pattern observed in Gram-negative LPS structures. Laboratory E. coli K-12 strains, including W3110 (lane 2), synthesize a truncated LPS molecule due to mutations in O-antigen synthesis genes. Smaller LPS molecules migrate further toward the bottom of these gels. All ΔrfaDFC mutant strains (compare lanes 2–4 with lanes 5–8) synthesize an even more truncated molecule, corresponding to the lack of core oligosaccharide, also known as deep rough mutation. The LPS profile shown is representative of at least three biological replicates.

Structural characterization of lipid material isolated from E. coli that produce minimal Kdo-lipid A domains mimetic of V. cholerae material

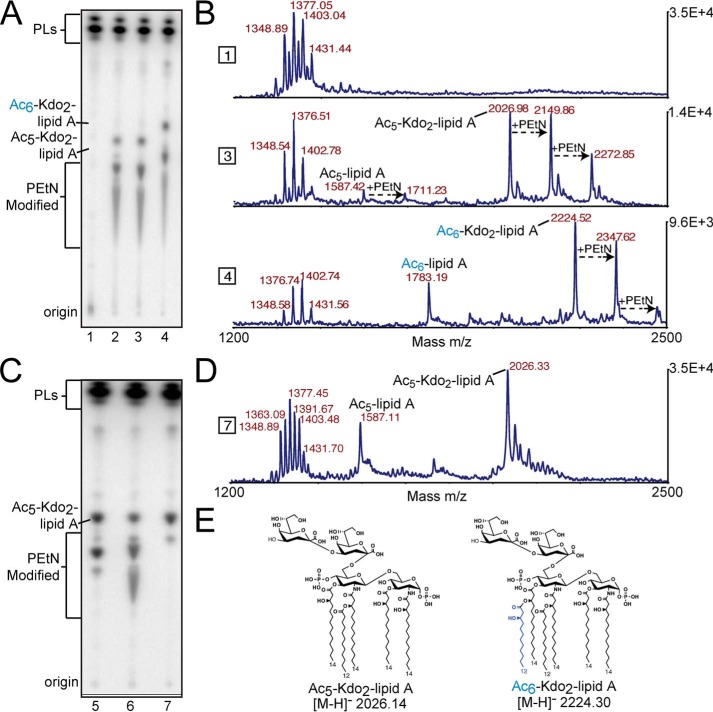

Observation of core-truncated Kdo2-lipid A made co-isolation of Kdo2-lipid A species with glycerophospholipids hypothetically possible with a simple two-phase chemical extraction. This would provide a more efficient workflow that circumvents additional steps used to chemically isolate and characterize lipid A material from Gram-negatives (23). Thin layer chromatography analysis of 32P-radioistopically labeled lipids, in a solvent system that resolves Kdo-lipid A species, showed E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT ΔrfaDFC contained lipid species not present in parental E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT (Fig. 3A; compare lane 2 versus 1). Expression of LpxN, the V. cholerae 3-hydroxylauryl transferase, increased the upward mobility of these lipid species as expected for hexa-acylation of penta-acylated material (Fig. 3A, compare lane 4 to 2 and 3).

Figure 3.

TLC and MALDI-MS structural analysis of biosynthetically engineered deep-rough E. coli that produce minimal Kdo-lipid A domains. Text labels along the plate depict origin where lipid material was spotted before TLC separation, as well as proposed lipid species. A, each lane represents lipid material from E. coli K12 W3110 ΔlpxMΔlpxT (lane 1), ΔlpxMΔlpxTΔrfaDFC (lane 2), ΔlpxMΔlpxTΔrfaDFC harboring pQlink (lane 3), or pQlink::LpxN (lane 4). B, MALDI-MS analysis of non-radiolabeled material in corresponding lanes in A. Right y axis denotes total counts, and the x axis is of the m/z range analyzed. C, each lane represents lipid material isolated from E. coli K12 W3110 ΔlpxMΔlpxTΔrfaDFCΔeptA (lane 5), ΔlpxMΔlpxTΔrfaDFCΔeptB (lane 6), or ΔlpxMΔlpxTΔrfaDFCΔeptAΔeptB (lane 7). D, MALDI-MS analysis of non-radiolabeled material in corresponding lanes in C. Right y axis denotes total counts, and the x axis is of the m/z range analyzed. E, major structures of penta-acylated or LpxN modified Kdo2-lipid A species in synthetically engineered E. coli. Other important structures can be found in supplemental Fig. S3.

MALDI-MS analyses of non-radioisotopically labeled lipids from these strains contain spectral peaks consistent with our interpretation of the structures deduced from TLC (Fig. 3B). Proposed structures of important singly charged molecular ions are included in (supplemental Fig. S3). The primary product of E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT ΔrfaDFC is a penta-acylated Kdo2-lipid A with an expected 2026.14 m/z (Fig. 3B). LpxN expression in this strain should produce a hexa-acylated Kdo2-lipid A with an expected 2224.3 m/z (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, MS-based structural analysis also indicated prevalent phosphoethanolamine-modified species (Fig. 3B; +123 m/z shift). A similar increase of phosphoethanolamine modification in rfa heptosyltransferase mutants has been previously reported (28). To simplify later experiments focused on AlmG-based glycine modification, deletion of both E. coli phosphoethanolamine transferases EptA and EptB was performed. TLC analysis shows a complete lack of phosphoethanolamine-modified Kdo-lipid A in E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT ΔrfaDFC ΔeptA ΔeptB (Fig. 3C). MALDI-MS analysis verified the chemical structure of isolated Kdo-lipid A material (Fig. 3, D and E). Construction of an E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT ΔrfaDFC ΔeptA ΔeptB mutant allowed production of a simple penta-acylated Kdo2-lipid A domain more facile to isolate than conventional lipid A isolation methods. Furthermore, we demonstrate here (Fig. 3, A and B), and in subsequent figures, that heterologous expression of LpxN allows production of hexa-acylated 3-hydroxylaurate Kdo2-lipid A in E. coli, the likely substrate for glycine modification by AlmEFG pathway enzymes.

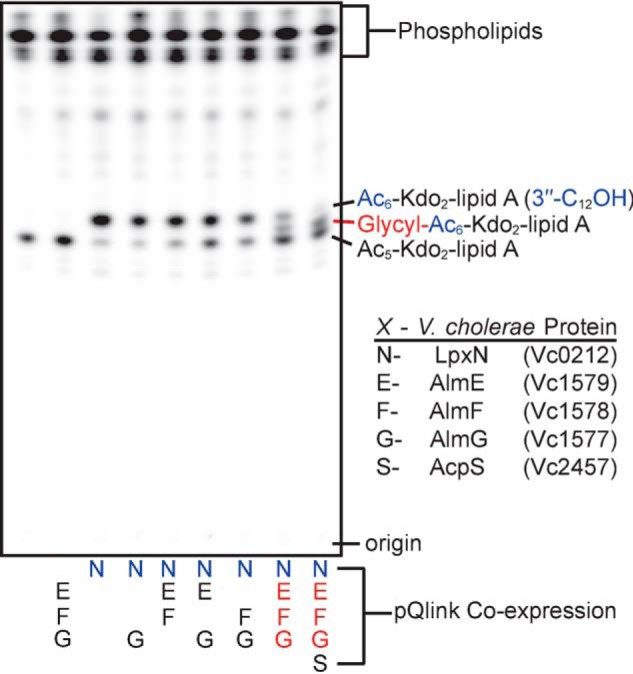

Analysis of lipids from E. coli-expressing V. cholerae enzymes shows requirement for AlmG in production of glycine-modified Kdo-lipid A domains

Combinations of AlmEFG and LpxN were co-expressed in the simplified Kdo2-lipid A-producing E. coli strain, to determine whether glycine modification was possible in an organism other than V. cholerae (Fig. 4). Combinatorial, co-expression constructs of V. cholerae proteins were created using the pQlink plasmid system, which enables IPTG-inducible expression of multiple, simultaneous gene products (24). Co-expression of AlmEFG and LpxN in E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT ΔrfaDFC ΔeptA ΔeptB resulted in expected TLC migration shifts for Kdo-lipid A material modified with glycine (Fig. 4, last two lanes). Glycine results in the addition of a positively charged residue, which in this TLC solvent system results in migration with lower mobile phase retention factors (spot shifts downward); similar to phosphoethanolamine-modified species (e.g. Fig. 3). The shift in phosphoethanolamine-modified species is more dramatic than glycine modification, as might be expected, due to the zwitterionic nature of phosphoethanolamine. Expression of the trio of AlmEFG proteins, without LpxN, did not affect migration of radiolabeled lipid species consistent with LpxN providing the appropriate 3-hydroxylauryl acyl chain as the site of glycine esterification (Fig. 4). Similarly AlmG is indispensable for glycine modification, where co-expression of LpxN, AlmF, and AlmE does not show evidence for glycine modification, consistent with the role of AlmG as a glycyltransferase. As Gly-AlmF is a co-substrate, the law of mass action would predict that increasing its intracellular concentration may push the AlmG-based glycine transfer reaction forward. Indeed, co-expression of Vc2457, which we previously identified as an AlmF-selective phosphopantetheinyltransferase (15), improved overall pathway efficiency as an increase in glycine modification was evident by TLC (Fig. 4, compare last two lanes). Vc2457 expression increases the available pool of holo-AlmF available for AlmE glycinylation (15).

Figure 4.

TLC analysis of isolated 32P-lipids from deep-rough E. coli that express V. cholerae glycine modification components. Each lane represents lipid material from E. coli K12 W3110 ΔlpxMΔlpxTΔrfaDFCΔeptAΔeptB harboring pQlink plasmids that heterologously express V. cholerae proteins indicated alphabetically below the plate (N, E, F, G, or S) and as detailed in the box legend (bottom right).

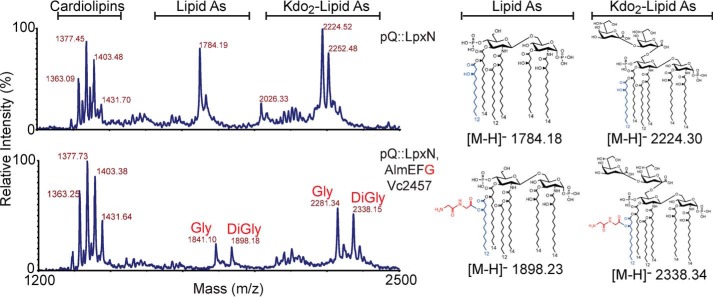

Predicted TLC structure assignments were supported by MALDI-MS (Fig. 5). Molecular ions consistent with 3″-hydroxylauryl containing lipid A and/or Kdo2-lipid A species were highly abundant upon expression of LpxN in E. coli ΔlpxM ΔlpxT ΔrfaDFC ΔeptA ΔeptB (Fig. 5; m/z 1784.2 and 2224.5). Co-expression of LpxN, AlmEFG, and Vc2457 reveals prominent spectral peaks indicative of glycine-modified (Fig. 5; m/z 1841.1 or 2281.3) and diglycine-modified (Fig. 5; m/z 1898.2 and 2338.2) lipid material, congruent with our TLC result (Fig. 4). Our previous structural analysis of V. cholerae biotype El Tor lipid A using more informative MSn also showed a mixed population of mono- and di-glycine-containing species (14). Efficiency of modification as observed by MALDI appears more robust than what was observed by TLC. Either di-glycinylated or mono-glycinylated lipid material might co-migrate with unmodified lipid in this solvent system, which complicates the use of TLC in determining overall modification efficiency. In this report MALDI and TLC data cohesively provide structural analysis in non-native E. coli that details the minimal requirements for glycine modification of Kdo-lipid A domains and the absolute requirement of AlmG in the final addition of glycine to target lipids. With our successful synthetic biology approach to characterization of the glycine modification pathway, we turned our attention to a more direct biochemical investigation of AlmG-based glycine transfer.

Figure 5.

MALDI-MS structural analysis of deep-rough E. coli that express V. cholerae glycine modification components. All spectra are from the same background strain of E. coli W3110 ΔlpxMΔlpxTΔrfaDFCΔeptAΔeptB. Lipids analyzed here correspond to strains from Fig. 4: W3110 ΔlpxMΔlpxTΔrfaDFCΔeptAΔeptB strains harboring pQlink plasmids expressing lpxN or lpxN, almEFG as indicated. MALDI-MS analyzed lipids were isolated from cultures grown without 32P. Left y axis denotes relative intensity and the x axis is of the m/z range analyzed.

Activity assessment of single-site AlmG alanine variants reveals an unusual catalytic domain within the LABLAT subgroup

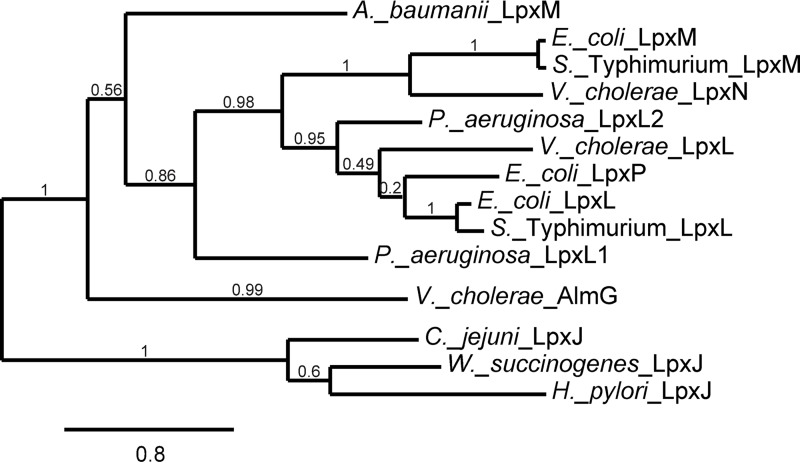

AlmG is distantly related to other members of the LABLAT subgroup, yet LABLAT members are the closest homologs in public databases of the apparently unique AlmG protein (Fig. 6; supplemental Fig. S4). A recently described clade within the LABLAT subgroup, LpxJ, responsible for transfer of acyl chains to secondary positions along associated Kdo-lipid A domains (6), is even more distantly related than AlmG (Fig. 6). Members of the expansive LPLAT superfamily typically feature an HX4(D/E) catalytic dyad proposed to be essential for activating hydroxyl nucleophiles for attack on thioester-linked acyl groups in transferase activity (25). AlmG contains two such candidate active-site dyads (106HX4D111 and 215HX4E220). This putative catalytic dyad is often positioned within a predicted hydrophobic cleft region, reasoned to be important for positioning of target lipid A acyl chain substrates (26–28). Based on current convention, the dyad at position His-106/Asp-111 is the most likely active-site dyad.

Figure 6.

Phylogram of experimentally verified representative members of the LABLAT subgroup. Maximum likelihood confidence values are reported for each branch. Branch lengths represent rate of difference in amino acid sequence, a distance legend is provided at the bottom. See under “Experimental procedures” and supplemental Fig. S4 for sequence information used to generate the phylogram.

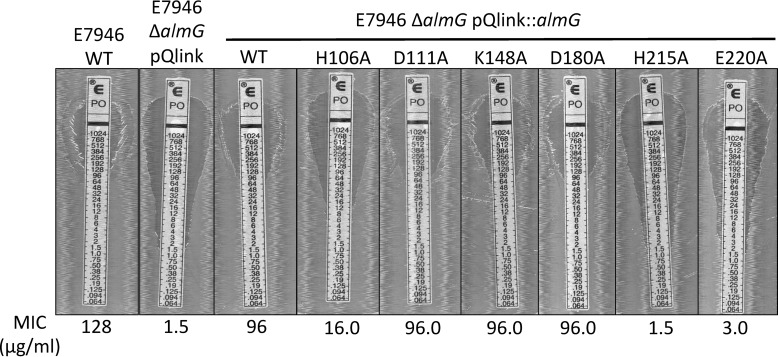

To assess the role of predicted catalytic residues, single residue alanine variants of AlmG were assessed. Glycine transfer activity was assessed via polymyxin B resistance in a V. cholerae ΔalmG mutant, an assay described in multiple studies that provides a rapid, physiologically relevant detection method for Kdo-lipid A chemical glycine modification in V. cholerae (14, 15, 29). Strains of V. cholerae El Tor ΔalmG were complemented with a pQlink vector, alone, expressing a wild-type copy of almG or single-site alanine variants (Fig. 7). No obvious growth phenotypes were observed in any strains tested. Contrary to other LABLATs, the His-106/Asp-111 dyad was not absolutely required for activity. Shockingly, the His-215/Glu-220 dyad was implicated as absolutely necessary for Kdo-lipid A domain glycine modification (Fig. 7). This site is not present in any other sequenced LABLAT member. Lys-148 was surprisingly dispensable for AlmG-based glycine transfer, a notable departure from the best biochemically characterized LABLAT subgroup member, LpxM from Acinetobacter baumannii, which has a spatially, chemically conserved arginine implicated in acyl transfer activity (30). D180A mutation also had no effect on AlmG glycine transferase activity. In sum, our AlmG functional assays, informed by the state of field biochemical data of conserved LABLAT catalytic motifs, conflate with its phylogeny (Fig. 6) to place AlmG as an unusual, potentially foundational clade within the LABLAT subgroup of the LPLAT superfamily. AlmG very likely uses His-215/Glu-220 for its apparent glycyltransferase activity, a catalytic element consistent with other LPLATs, albeit at a different site. A more detailed description of AlmG activity awaits further elucidation.

Figure 7.

Expression of single site AlmG alanine variants in V. cholerae ΔalmG strains. The determined MIC value is reported below each image. Strains tested include E7946 wild type (WT), a positive control, and E7946 ΔalmG strains harboring pQlink expression plasmids that contain no gene (negative control), wild-type copy (complemented), or single-site AlmG alanine variants as indicated above each image. Representative plates imaged from experiments performed in triplicate are shown.

Discussion

AlmG does not contain predicted transmembrane helical regions characteristic of bacterial integral membrane proteins (31), and it is most likely a peripheral membrane protein. The general hydropathy of AlmG is relatively high with multiple hydrophobic clusters predicted (32). Combined with a very basic theoretical pI (9.49), these features hint at favorable interactions with acidic, hydrophobic phospholipids of the inner bacterial membrane. As glycinylated AlmF is restricted to the cytosol (33), the substrate donor molecule for glycine transfer, AlmG's residence on the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane bilayer is most sensible. MALDI-MS and TLC analysis of lipid material from E. coli hosts expressing Alm, and other necessary enzymes, support the assignment of V. cholerae AlmG as a bona fide glycyltransferase of distant relation to LABLAT subgroup members, yet it is no more distant than the LpxJ clade (6).

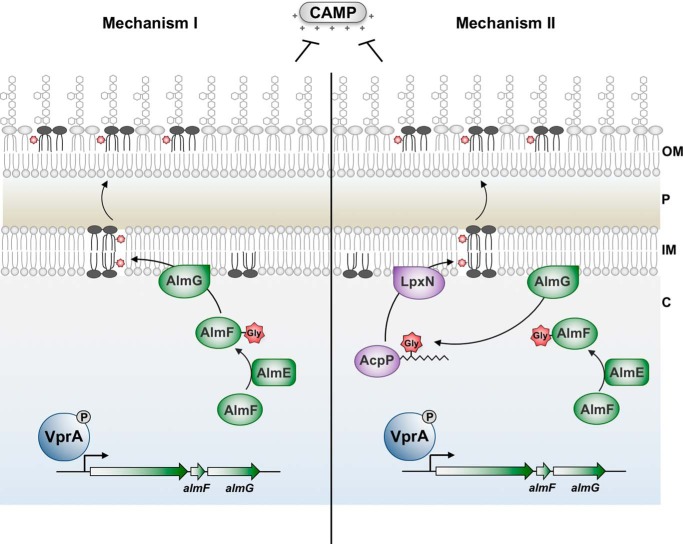

A recent report elegantly providing the first LPLAT structure, LpxM from A. baumannii, put forth compelling evidence for bifunctional activity of a LABLAT subgroup member (30). This secondary acyltransferase homolog catalyzes not only the transfer of hydrocarbon acyl chains to substrate Kdo-lipid A domains but also displays a thioesterase activity against co-substrate acyl-ACPs. Thioesterase activity in this context would release covalently bound hydrocarbon acyl chains on associated carrier proteins. Albeit tendentious, this indicates that LPLAT members, with A. baumannii LpxM bifunctionality, can liberate fatty acids for redirection into catabolic pathways, because acyl-ACPs are generally fated for anabolic reactions during growth. The signal for metabolic redirection would be lack of sufficient Kdo-lipid A substrate as might occur during metabolic starvation, and as reported A. baumannii LpxM thioesterase activity occurs when lipid co-substrates are in absentia (i.e. only acyl-ACP is bound). Interestingly, LpxM from A. baumannii presents the closest related member of the LABLAT family to AlmG, still quite a distant relation (Fig. 6). For the above reasons, an alternative mechanism of AlmG glycyl transfer is likely, where direct transfer to Kdo-lipid A domains may not occur. In combination with the dual active-site hypothesis for LpxM of A. baumannii, we present an alternative, plausible route for glycine modification of Kdo-lipid A domains. Glycine may be transferred to 3-hydroxylauryl ACPs, where LpxN transfers a resultant glycinylated acyl chain to Kdo-lipid A domains (Fig. 8). Isolation of a glycinylated 3-hydroxylauryl intermediate would provide convincing evidence for this mechanism.

Figure 8.

Unusual AlmG catalytic residues suggest an alternative mechanism for synthesis of glycine-modified Kdo-lipid A domains. Both hypothetical mechanisms begin with phosphorylated VprA directly promoting expression of the almEFG operon. In a two-step catalytic mechanism, AlmE (Vc1579) generates glycyl-AMP from glycine and ATP to activate glycine for transfer onto carrier protein holo-AlmF (Vc1578). Holo-AlmF is generated after 4′-phosphopantetheinyl of coenzyme A is transferred onto apo-AlmF by the phosphopantetheinyl transferase AcpS (Vc2457). In mechanism I (left), AlmG at the inner membrane uses glycyl-AlmF as the aminoacyl donor for transfer onto the secondary hydroxylauryl acyl chain of V. cholerae hexaacylated-monophosphoryl-Kdo-lipid A. At least two rounds of glycine transfer can occur. In mechanism II (right), AlmG uses glycyl-AlmF to transfer glycine onto hydroxyl-lauryl acyl carrier protein (AcpP; Vc2020). Two rounds of glycine transfer can occur. LpxN then transfers glycyl-3-hydroxylaurate from AcpP onto pentaacylated-monophosphoryl-Kdo-lipid A. In either mechanism, diglycine or glycine-modified lipid A is then transported to the bacterial surface to provide resistance against cationic antimicrobial peptides such as polymyxin. OM, outer membrane; P, periplasm; IM, inner membrane.

Our laboratory recently reported that V. cholerae El Tor has maintained a second LPS modification to promote polymyxin resistance through the addition of phosphoethanolamine residues to lipid A phosphate groups (34). The Vibrio EptA homolog is similar to pEtN transferases found in other pathogens, including Neisseria meningitidis, Salmonella enterica, Campylobacter jejuni, and pathogenic E. coli. Phosphoethanolamine transferase activity occurs in the periplasmic compartment. Substrate competition between lipid A modification enzymes has been reported (35). During development of the E. coli synthetic biology approach to study glycine modification in this report, EptA and EptB were capable of phosphoethanolamine transfer onto glycinylated Kdo-lipid A domains (supplemental Fig. 5 and 6). Similarly V. cholerae EptA is capable of phosphoethanolamine transfer to glycinylated substrates (34). Thus phosphoethanolamine and glycine transfer does not occur at the level of enzymatic substrate specificity. However, there is coordinated control of LPS glycine and phosphoethanolamine modifications in V. cholerae at the transcriptional level. The responsible regulatory network has not been sorted out, but we do know that expression of eptA is not controlled by the AlmEFG transcriptional regulator VprA (34, 36).

Aminoacylation of bacterial surface membranes is an emergent paradigm in microbial resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides. Gram-positive bacteria neutralize their cell walls by transferring d-alanine to surface teichoic acids, poly-phosphoribitol, or poly-phosphoglycerol chains linked to glycerophospholipids or N-acetylmuramic acid of surface-exposed peptidoglycan (16, 37–39). Although the genes dltBD of the dltDABC operon (40) have long been identified as responsible for the final chemical transfer step, from d-alanine-linked carrier proteins (DltC) to surface molecules, the precise molecular details of the DltBD reaction remain to be elucidated. Recent data have clarified that DltC, the carrier molecule of d-alanine, analogous to Gly-AlmF, is not exported, consistent with aminoacyl transfer activity being localized to the cytoplasm (41). Continued exploration of this system in Gram-positives will hopefully clarify these important steps, in a modification with tremendous physiological importance, particularly in pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus and other Firmicutes like Listeria, Bacillus, Enterococcus, or Streptococcus spp. (41).

Kdo-lipid A glycinylation is a unique Gram-negative strategy necessary for resistance to CAMPs (14). AlmEFG catalyzes the adenylation of an amino acid (like DltA), subsequent transfer to a carrier protein (like DltA to DltC), and final transfer to a surface component by dedicated transferase machinery (as DltBD). An important consideration regarding the activity of AlmG is apparent specificity for Gly-AlmF. Detailed molecular investigation of wild-type V. cholerae AlmE, demonstrated that its substrate holo-AlmF could, in addition to glycine, carry l-alanine as evidenced upon in vitro characterization (15). Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support the existence of l-Ala-AlmF in vivo (15). AlmG certainly does not use l-Ala-AlmF to decorate Kdo-lipid A domains as l-Ala-Kdo-lipid A is not apparent either in MALDI-MS analysis of isolated lipid material from E. coli or V. cholerae (e.g. Figs. 3 and 7 and supplemental Fig. 6) (14). Finally, as diglycine-modified Kdo-lipid A species are apparent in both E. coli (Fig. 3, 7, and supplemental Fig. 6) and V. cholerae (14), it would appear that if any flexibility exists in AlmG specificity, it involves chemistry for at least two rounds of glycine to lipid substrate transfer. Multiple rounds of amino acid transfer to the same molecule have not been reported with DltBD-like enzymes. As a final note, glycine-modified sugars of core-oligosaccharide LPS have also been reported in multiple organisms, including C. jejuni, Haemophilus influenzae, and Shigella flexneri (42–44); however, enzymes responsible for this observed activity await identification. A recent study on the chemical composition of V. cholerae exopolysaccharide also showed its decorated with glycine residues, catalyzed by a hitherto unidentified enzyme (45).

Evidence in this report supports the hypothesis that AlmG functions as a glycyltransferase and characterizes a potential founding member of an outlying clade within the LABLAT subgroup of the LPLAT superfamily. However, this distinction awaits deposition of more closely related sequences within public databases. The paucity of terrestrial bacterial sequences, with high similarity to AlmG, is remarkable. Genomes of marine bacteria are difficult to obtain as a result of sampling difficulties (46–48). Vibrio is one of the most facile groups of marine microorganisms to culture and is an important oceanic model organism. How fitting that an organism with dual lifestyles between the oceanic hydrosphere and centuries long evolution as a human pathogen provides our first glimpse of this newly described glycyl to lipid transfer activity.

Experimental procedures

Materials

General chemicals used in this report were purchased from Sigma or Thermo Fisher Scientific unless indicated otherwise. 32Pi used to label bacterial phospholipids was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences at a specific concentration of 10 μCi/μl.

Bacterial growth

Bacterial strains used or generated in this report are listed in supplemental Table S1. V. cholerae and E. coli were routinely grown at 37 °C on LB or LB agar unless otherwise indicated. As appropriate, antibiotics were supplemented in growth media at the following concentrations: 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 50 μg/ml kanamycin, 100 μg/ml ampicillin, and 10 μg/ml streptomycin.

Recombinant DNA

Plasmids (supplemental Table S2) and oligonucleotides (supplemental Table S3) are reported in the supplemental material. Genomic DNA was routinely isolated using the Easy DNA kit (Life Sciences). Custom primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. PCR reagents were purchased from Takara, New England Biolabs, or Stratagene, and PCR products were routinely isolated using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). To create pQlink plasmids used for co-expression of multiple genes, reagents purchased from Invitrogen were used for ligation-independent cloning, as described previously (24). All plasmids constructed in this study were initially transformed into chemically competent E. coli XL-1 Blue storage strain before transformation into the particular strain for a given experiment. Plasmid promoter and gene-insert sequences were verified by DNA sequencing at the ICMB Core Facility at the University of Texas at Austin or with Genewiz.

Alignment and phylogenetic analysis of representative LABLAT members with AlmG

Sequences were obtained either from NCBI or KEGG databases. Alignments were performed using Clustal Omega (49). Phylogram construction used the phylogeny.fr suite (50).

Synthetic biology of E. coli that produce minimal Kdo-lipid A domains

Construction of gene deletion strains of E. coli, except ΔrfaDFC, were performed via P1 vir phage transduction according to previously published methodologies, with Keio collection E. coli deletion mutants (GE Dharmacon). Lambda red recombineering was used to generate ΔrfaDFC mutants according to previously published protocols (22). Modifications to the general procedure include supplementation of outgrowth cultures with 1 mm arabinose and incubation at 30 °C. Markerless deletion mutants were subsequently generated according to published protocols with yeast Flp recombinase machinery encoded on a pcp20 suicide vector (22). In multiple deletion strains, P1 transduction was followed by marker removal, before subsequent deletions were introduced. Recombineering was always the last step, as ΔrfaDFC severely limits binding of P1 vir phage; phage tail proteins specifically interact with the core-oligosaccharide portion of LPS (51). Correct strain construction was verified by PCR, TLC analysis of 32P-radiolabeled, or MALDI-MS analysis of non-radiolabeled lipid products, and ProQ Emerald-based detection of gel separated LPS.

Procedure to visualize LPS by ProQ® Emerald fluorescent dye

Bacteria were grown in LB media at 30 °C until mid-exponential phase. Cell amounts were normalized based on optical density, harvested, and resuspended in Tricine-buffered Laemmli sample buffer (with 4% β-mercaptoethanol), followed by proteinase K digestion overnight at 55 °C to remove contaminant protein. Resultant material containing intact LPS is boiled at 100 °C before resolution by Tricine, SDS-10–20% PAGE. Electrophoresis was performed at 4 °C, typically for 2 h. In-gel oxidation of associated carbohydrate was followed with visualization of LPS using a fluorescence-based molecular probe according to the manufacturer's protocols (Pro-Q® Emerald Life Technologies, Inc.).

General procedure for co-isolation of glycerophospholipid and Kdo2-lipid A species

A single colony of bacteria was used to inoculate 5 ml of media (LB or G56 media, supplemented with 100 μm IPTG or antibiotic) and grown overnight at 37 or at 30 °C for ΔrfaDFC strains. The next day, a 10-ml culture was inoculated to a starting A600 of ∼0.05, grown in a 20 × 150-mm disposable glass culture tube. Growth media for TLC analysis was supplemented with 10 μCi/ml of 32P. Cells were grown to mid-exponential phase, to an A600 of 0.8–1.0. Cells were then harvested in 16 × 125-mm glass centrifuge tubes with PTFE-lined cap using a fixed angle clinical centrifuge at 1,500 × g for 12 min. Supernatant was removed into an appropriate radioactive waste container. Cell pellets were washed with 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and centrifuged again for 10 min at 1,500 × g. Supernatant was discarded, and cells were resuspended in 5 ml of single-phase Bligh-Dyer mixture consisting of chloroform/methanol/water (1:2:0.8, v/v/v), mixed by vortex, and incubated at room temperature for 20–30 min to ensure complete chemical cell lysis. These mixtures were centrifuged in a clinical centrifuge at 1,500 × g for 15 min. Supernatant, which contains glycerophospholipids, isoprenyl lipids, free lipid A, and Kdo-lipid A domains, was then transferred into clean 16 × 125-mm glass centrifuge tubes and converted into a two-phase Bligh-Dyer mixture by adding 1 ml of chloroform and 1 ml of methanol, yielding a chloroform/methanol/aqueous (2:2:1.8 v/v) mixture. This mixture was vortexed for ∼30 s and then centrifuged for 12 min in a clinical centrifuge at 1,500 × g to separate the organic and aqueous phases. The lower organic phase was removed into a clean glass centrifuge tube using a glass Pasteur pipette. A second extraction was performed by adding 2 ml of pre-equilibrated two-phase Bligh-Dyer lower phase (2:2:1.8; v/v/v; chloroform/methanol/PBS, pH 7.5) to the remaining upper phase. This material was vortexed and centrifuged as before. The lower phase was combined with the previous lower phase, and 7.6 ml of pre-equilibrated upper phase was added to yield a final two-phase Bligh-Dyer solution (chloroform/methanol/water; 2:2:1.8, v/v/v). Material was vortexed and centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 12 min, and the lower phase was transferred to a clean glass tube where isolated lipid material was dried using a nitrogen stream dryer. Dried samples were used right away or were transferred to smaller containers by resuspension in 4:1 v/v chloroform/methanol, then re-dried, and/or routinely stored as dried material at −20 °C until further use.

TLC to analyze 32P radioisotopically labeled phospholipids

TLC mobile phase solvent system was prepared in a clean TLC tank with ∼40 cm of chromatography paper to accommodate a 10 × 20- or 20 × 20-cm Silica Gel 60 plate. In this report, we used pyridine, 88% formic acid, water, 30:70:16:10, v/v/v, and allowed to pre-equilibrate for at least 3 h, usually overnight. 32P-Labeled sample was typically dissolved in 500 μl of 4:1 chloroform/methanol (v/v), vortexed, and bath sonicated to completely dissolve lipid material. 5 μl of lipid sample was added to a scintillation vial containing 5 ml of scintillation mixture and counted in a scintillation counter to enable calculation of total counts per min of sample. With a microcapillary pipette, 20,000–50,000 cpm per sample was spotted onto the silica plate origin and allowed to air dry (>15 min). TLC plates were then placed into a pre-equilibrated tank (solvent system indicated in figure legends) and run for ∼3 h until mobile phase reached the top of the plate. Plates were dried and exposed to a phosphorimaging screen.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry to structurally characterize isolated phospholipid species

Typically, the dried lipid A samples were transferred in microvials, where material was resuspended in ∼50 μl of chloroform/methanol (4:1, v/v) and vortexed/sonicated to obtain an ∼1–5 μg/μl lipid A solution when extracted from E. coli. Azothiothymine matrix was prepared by mixing a saturated 6-aza-2-thiothymine in 50% acetonitrile solution with saturated tribasic ammonium citrate (20:1, v/v). Mixtures were vortexed and centrifuged, before 0.5 μl was spotted on MALDI plate. 0.5 μl of lipid sample was typically deposited onto the previously spotted ATT matrix and mixed on plate. MALDI-MS data were calibrated using calibration 1 and calibration 2 mixtures from Anaspec peptide mass standards in negative mode. Spectra were acquired in the linear negative mode on a Voyager-DE (AB Biosystems) by scanning for optimal ion signals, with a minimum of 300 laser shots per spectra. Samples were diluted or concentrated as needed to generate high-quality spectra. Typical voltage parameters included 20,000 V, 95% grid voltage, 0.002 guide wire voltage, and a delay time of 150 ns. A low mass gate at 500 Da was also employed.

Polymyxin B MIC determination

Mid-exponential V. cholerae strains were diluted (1:50) in fresh media and sterilely applied to LB agar plates supplemented with 1 mm IPTG. Polymyxin B E-strip® tests were added to the plate and allowed to incubate overnight, where confluent bacterial growth occurs at antibiotic levels below the MIC.

Author contributions

J. C. H. and M. T. conceptualization; J. C. H. and C. M. H. data curation; J. C. H., C. M. H., and M. T. formal analysis; J. C. H. investigation; J. C. H., C. M. H., and M. T. methodology; J. C. H. writing original draft; J. C. H., C. M. H., and M. T. writing review and editing; M. T. supervision; M. T. funding acquisition; M. T. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jessica V. Hankins for the foundational work on Vibrio cholerae lipid A. We also thank the late Prof. Christian R. H. Raetz. Your last student finally graduated, so raise your glass from beyond. Stephen and Jeremy are eternally grateful for your mentorship. You're sorely missed. Cheers!

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant RO1 AI076322 (to M. S. T.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article was selected as one of our Editors' Picks.

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–6 and Tables 1–3.

- LPLAT

- lysophosphospholipid acyltransferase

- CAMP

- cationic antimicrobial peptide

- LABLAT

- lipid A biosynthesis late acyltransferase

- Kdo

- keto-deoxyoctulosonate

- IPTG

- isopropyl β-d-1 thiogalactopyranoside

- ACP

- acyl carrier protein

- MIC

- minimum inhibitory concentration

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine.

References

- 1. Oger P. M. (2015) Homeoviscous adaptation of membranes in archaea. Subcell. Biochem. 72, 383–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang Y.-M., and Rock C. O. (2008) Membrane lipid homeostasis in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 222–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ernst R., Ejsing C. S., and Antonny B. (2016) Homeoviscous adaptation and the regulation of membrane lipids. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 4776–4791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clementz T., Bednarski J. J., and Raetz C. R. (1996) Function of the htrB high temperature gene of Escherichia coli in the acylation of lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 12095–12102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vorachek-Warren M. K., Carty S. M., Lin S., Cotter R. J., and Raetz C. R. (2002) An Escherichia coli mutant lacking the cold shock-induced palmitoleoyltransferase of lipid A biosynthesis. Absence of unsaturated acyl chains and antibiotic hypersensitivity at 12 °C. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 14186–14193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rubin E. J., O'Brien J. P., Ivanov P. L., Brodbelt J. S., and Trent M. S. (2014) Identification of a broad family of lipid A late acyltransferases with non-canonical substrate specificity. Mol. Microbiol. 91, 887–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raetz C. R., and Whitfield C. (2002) Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 635–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raetz C. R., Reynolds C. M., Trent M. S., and Bishop R. E. (2007) Lipid A modification systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 295–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boll J. M., Tucker A. T., Klein D. R., Beltran A. M., Brodbelt J. S., Davies B. W., and Trent M. S. (2015) Reinforcing lipid A acylation on the cell surface of Acinetobacter baumannii promotes cationic antimicrobial peptide resistance and desiccation survival. MBio. 6, e00478–00415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hankins J. V., Madsen J. A., Giles D. K., Childers B. M., Klose K. E., Brodbelt J. S., and Trent M. S. (2011) Elucidation of a novel Vibrio cholerae lipid A secondary hydroxy-acyltransferase and its role in innate immune recognition. Mol. Microbiol. 81, 1313–1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ali M., Lopez A. L., You Y. A., Kim Y. E., Sah B., Maskery B., and Clemens J. (2012) The global burden of cholera. Bull. World Health Organ. 90, 209–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tran A. X., Lester M. E., Stead C. M., Raetz C. R., Maskell D. J., McGrath S. C., Cotter R. J., and Trent M. S. (2005) Resistance to the antimicrobial peptide polymyxin requires myristoylation of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium lipid A. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28186–28194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clements A., Tull D., Jenney A. W., Farn J. L., Kim S.-H., Bishop R. E., McPhee J. B., Hancock R. E., Hartland E. L., Pearse M. J., Wijburg O. L., Jackson D. C., McConville M. J., and Strugnell R. A. (2007) Secondary acylation of Klebsiella pneumoniae lipopolysaccharide contributes to sensitivity to antibacterial peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 15569–15577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hankins J. V., Madsen J. A., Giles D. K., Brodbelt J. S., and Trent M. S. (2012) Amino acid addition to Vibrio cholerae LPS establishes a link between surface remodeling in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8722–8727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henderson J. C., Fage C. D., Cannon J. R., Brodbelt J. S., Keatinge-Clay A. T., and Trent M. S. (2014) Antimicrobial peptide resistance of Vibrio cholerae results from an LPS modification pathway related to non-ribosomal peptide synthetases. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 2382–2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neuhaus F. C., and Baddiley J. (2003) A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of d-alanyl-teichoic acids in Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 686–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hankins J. V., and Trent M. S. (2009) Secondary acylation of Vibrio cholerae lipopolysaccharide requires phosphorylation of Kdo. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25804–25812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Needham B. D., and Trent M. S. (2013) Fortifying the barrier: the impact of lipid A remodelling on bacterial pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 467–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Needham B. D., Carroll S. M., Giles D. K., Georgiou G., Whiteley M., and Trent M. S. (2013) Modulating the innate immune response by combinatorial engineering of endotoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1464–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brabetz W., Müller-Loennies S., Holst O., and Brade H. (1997) Deletion of the heptosyltransferase genes rfaC and rfaF in Escherichia coli K-12 results in an re-type lipopolysaccharide with a high degree of 2-aminoethanol phosphate substitution. Eur. J. Biochem. 247, 716–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang J., Ma W., Wang Z., Li Y., and Wang X. (2014) Construction and characterization of an Escherichia coli mutant producing Kdo2-lipid A. Marine Drugs 12, 1495–1511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Datsenko K. A., and Wanner B. L. (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Henderson J. C., O'Brien J. P., Brodbelt J. S., and Trent M. S. (2013) Isolation and chemical characterization of lipid A from Gram-negative bacteria. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, e50623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scheich C., Kümmel D., Soumailakakis D., Heinemann U., and Büssow K. (2007) Vectors for co-expression of an unrestricted number of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, e43–e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hishikawa D., Shindou H., Kobayashi S., Nakanishi H., Taguchi R., and Shimizu T. (2008) Discovery of a lysophospholipid acyltransferase family essential for membrane asymmetry and diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2830–2835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heath R. J., and Rock C. O. (1998) A conserved histidine is essential for glycerolipid acyltransferase catalysis. J. Bacteriol. 180, 1425–1430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Röttig A., and Steinbüchel A. (2013) Acyltransferases in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77, 277–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Six D. A., Carty S. M., Guan Z., and Raetz C. R. (2008) Purification and mutagenesis of LpxL, the lauroyltransferase of Escherichia coli lipid A biosynthesis. Biochemistry 47, 8623–8637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Herrera C. M., Crofts A. A., Henderson J. C., Pingali S. C., Davies B. W., and Trent M. S. (2014) The Vibrio cholerae VprA-VprB two-component system controls virulence through endotoxin modification. mBio. 5, e02283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dovala D., Rath C. M., Hu Q., Sawyer W. S., Shia S., Elling R. A., Knapp M. S., and Metzger L. E. 4th (2016) Structure-guided enzymology of the lipid A acyltransferase LpxM reveals a dual activity mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E6064–E6071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krogh A., Larsson B., von Heijne G., and Sonnhammer E. L. (2001) Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Callebaut I., Labesse G., Durand P., Poupon A., Canard L., Chomilier J., Henrissat B., and Mornon J. P. (1997) Deciphering protein sequence information through hydrophobic cluster analysis (HCA): current status and perspectives. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 53, 621–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Petersen T. N., Brunak S., von Heijne G., and Nielsen H. (2011) SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods 8, 785–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herrera C. M., Henderson J. C., Crofts A. A., and Trent M. S. (2017) Novel coordination of lipopolysaccharide modifications in Vibrio cholerae promotes CAMP resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 10.1111/mmi.13835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herrera C. M., Hankins J. V., and Trent M. S. (2010) Activation of PmrA inhibits LpxT-dependent phosphorylation of lipid A promoting resistance to antimicrobial peptides: phosphorylation of lipid A inhibits pEtN addition. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 1444–1460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bilecen K., Fong J. C., Cheng A., Jones C. J., Zamorano-Sánchez D., and Yildiz F. H. (2015) Polymyxin B resistance and biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae are controlled by the response regulator CarR. Infect. Immun. 83, 1199–1209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Percy M. G., and Gründling A. (2014) Lipoteichoic acid synthesis and function in Gram-positive bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 68, 81–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pasquina L. W., Santa Maria J. P., and Walker S. (2013) Teichoic acid biosynthesis as an antibiotic target. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 16, 531–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brown S., Xia G., Luhachack L. G., Campbell J., Meredith T. C., Chen C., Winstel V., Gekeler C., Irazoqui J. E., Peschel A., and Walker S. (2012) Methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus requires glycosylated wall teichoic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18909–18914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Perego M., Glaser P., Minutello A., Strauch M. A., Leopold K., and Fischer W. (1995) Incorporation of d-alanine into lipoteichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis. Identification of genes and regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 15598–15606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reichmann N. T., Cassona C. P., and Gründling A. (2013) Revised mechanism of d-alanine incorporation into cell wall polymers in Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology 159, 1868–1877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Molinaro A., Silipo A., Castro C. D., Sturiale L., Nigro G., Garozzo D., Bernardini M. L., Lanzetta R., and Parrilli M. (2008) Full structural characterization of Shigella flexneri M90T serotype 5 wild-type R-LPS and its galU mutant: glycine residue location in the inner core of the lipopolysaccharide. Glycobiology 18, 260–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Engskog M. K., Deadman M., Li J., Hood D. W., and Schweda E. K. (2011) Detailed structural features of lipopolysaccharide glycoforms in nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae strain 2019. Carbohydr. Res. 346, 1241–1249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dzieciatkowska M., Brochu D., van Belkum A., Heikema A. P., Yuki N., Houliston R. S., Richards J. C., Gilbert M., and Li J. (2007) Mass spectrometric analysis of intact lipooligosaccharide: direct evidence for O-acetylated sialic acids and discovery of O-linked glycine expressed by Campylobacter jejuni. Biochemistry 46, 14704–14714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yildiz F., Fong J., Sadovskaya I., Grard T., and Vinogradov E. (2014) Structural characterization of the extracellular polysaccharide from Vibrio cholerae O1 El-Tor. PLoS ONE 9, e86751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yooseph S., Sutton G., Rusch D. B., Halpern A. L., Williamson S. J., Remington K., Eisen J. A., Heidelberg K. B., Manning G., Li W., Jaroszewski L., Cieplak P., Miller C. S., Li H., Mashiyama S. T., et al. (2007) The Sorcerer II Global Ocean Sampling expedition: expanding the universe of protein families. PLoS Biol. 5, e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hug L. A., Baker B. J., Anantharaman K., Brown C. T., Probst A. J., Castelle C. J., Butterfield C. N., Hernsdorf A. W., Amano Y., Ise K., Suzuki Y., Dudek N., Relman D. A., Finstad K. M., Amundson R., Thomas B. C., and Banfield J. F. (2016) A new view of the tree of life. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yilmaz P., Yarza P., Rapp J. Z., and Glöckner F. O. (2015) Expanding the world of marine bacterial and archaeal clades. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sievers F., and Higgins D. G. (2014) Clustal Omega, accurate alignment of very large numbers of sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 1079, 105–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dereeper A., Guignon V., Blanc G., Audic S., Buffet S., Chevenet F., Dufayard J.-F., Guindon S., Lefort V., Lescot M., Claverie J.-M., and Gascuel O. (2008) Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W465–W469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Liu J., Chen C.-Y., Shiomi D., Niki H., and Margolin W. (2011) Visualization of bacteriophage P1 infection by cryo-electron tomography of tiny Escherichia coli. Virology 417, 304–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.