Abstract

We report two cases of Vascular Eagle’s Syndrome, which demonstrate two distinct mechanisms of cerebral ischemia. In the first case, hemodynamic transient cerebral ischemia arose as a direct result of compression of the internal carotid artery (ICA). In the second, embolic large left middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarction as a result of a thrombus from a pseudoaneurysmal dilatation of the left ICA.

Keywords: Eagle Syndrome, Carotid Thromboembolism, Carotid Pseudoaneurysm, Positional Cerebral Ischemia, Thromboembolic Stroke, Brain, Carotid Artery, MRI, CT, CT Angiography

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 69-year-old male presented with a history of intermittent left arm weakness and numbness upon turning his head to the right. This was not always reproducible on examination and he was otherwise neurologically intact. His past clinical history was significant for a right carotid endarterectomy 14 months prior to his presentation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and a 20 pack-year smoking history. CT arteriogram (CTA) demonstrated expected post-surgical changes at the endarterectomy site and an elongated styloid process that crossed the internal carotid medial to the angle of the mandible and extended to the hyoid bone (Figure 1). Moreover, the anterior and right posterior communicating arteries were absent and this was best demonstrated on the three 3-dimensional (3D) CTA (Figure 2).

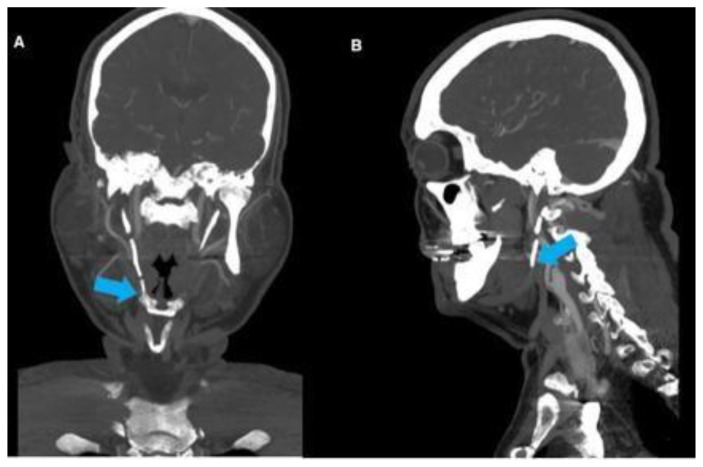

Figure 1.

69-year-old male with compression of the right ICA secondary to Eagle’s syndrome.

FINDINGS: Coronal (Fig. 1A) and Sagittal (Fig. 1B) contrast enhanced CT of the head and neck demonstrate post-endarterectomy appearance of the right ICA with an ipsilateral significantly elongated styloid process (arrows).

TECHNIQUE: Coronal (Fig. 1A) and Sagittal (Fig 1B) CTA, 3 mm slice thickness using Visipaque (320 mgl/ml) injected at a rate of 5 ml/sec for a total volume of 65 ml.

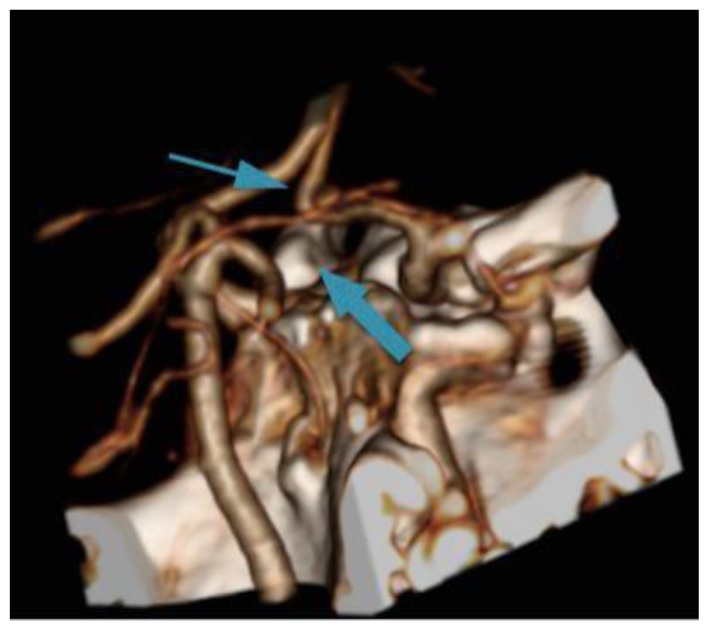

Figure 2.

69-year-old male with compression of the right ICA secondary to Eagle’s Syndrome.

FINDINGS: 3D CTA of the Circle of Willis demonstrates absent AComm (thin arrow) and absent PComm arteries (thick arrow). The arrows are pointing to the usual anatomical locations of both vessels.

TECHNIQUE: 3D reconstruction from a 3 mm slice thickness CTA using Visipaque (320 mgl/ml) injected at a rate of 5 ml/sec for a total volume of 65 ml

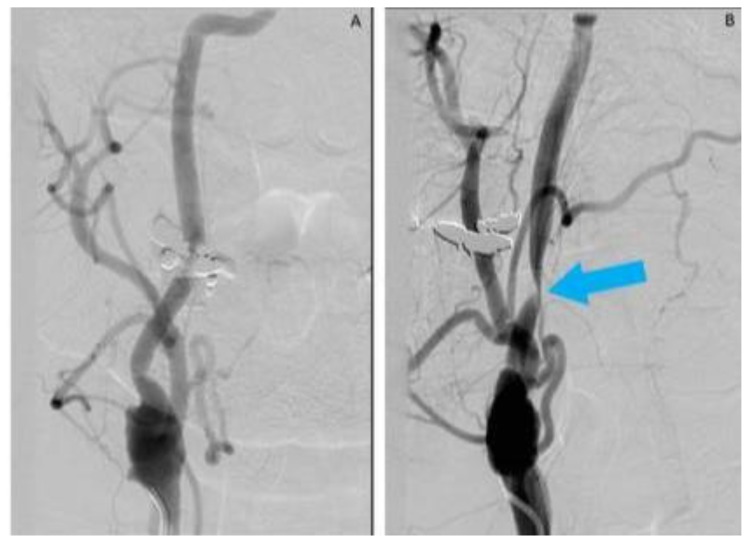

Catheter angiography demonstrated no significant ICA narrowing with the head in neutral position (Figure 3A). When the head was turned to the right, catheter angiography showed significant right ICA stenosis where the ossified stylohyoid crossed the ICA (Figure 3B). The patient experienced pre-syncopal episode and left arm weakness in that position during the angiography.

Figure 3.

69-year-old male with compression of the right ICA secondary to Eagle’s syndrome.

FINDINGS: Catheter angiogram in the arterial phase demonstrates normal filling in the post-endarectomy right ICA (Fig. 3A). When the patient turns his head to the right (Fig. 3B), severe right ICA stenosis is noted (arrow).

TECHNIQUE: Catheter angiogram of right common carotid artery using Omnipaque 300 (300mgl/ml) with the injection rate of 5 ml/sec for total volume of 12 ml.

Case 2

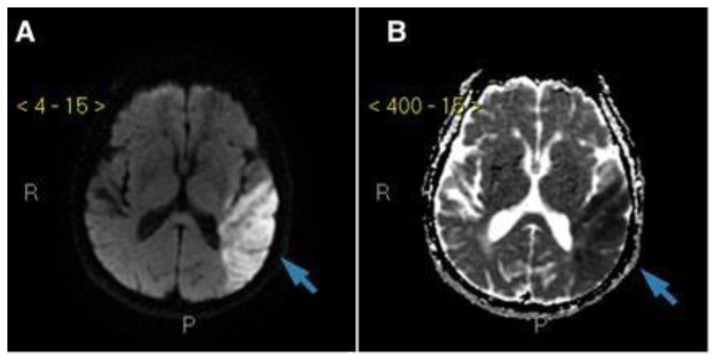

An 85-year-old male presented to a community hospital with receptive and expressive aphasia, right facial droop, right hemiparesis and right-side gaze preference. His motor symptoms resolved over a number of days but his aphasia persisted so he was referred to a tertiary care centre for assessment. His past medical history was significant for a left lobar hemorrhage 5 years ago, chronic renal disease and dyslipidemia. He was a non-smoker. EKG and Echocardiography demonstrated neither atrial fibrillation nor cardiac thrombus. CTA demonstrated an 8 mm pseudoaneurysm of the left ICA at the level of the second cervical vertebra containing a thrombus along with an ossified stylohyoid ligament adjacent to the pseudoaneurysm (Figures 4 and 5A). Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) on a three-tesla magnetic resonance imaging (3-T MRI) showed a left middle cerebral artery territory infarction (Figure 6). Follow-up imaging with CT arteriogram one year later demonstrated resolution of the pseudoaneurysmal thrombus, which had likely embolized to cause the infarction (Figure 5B).

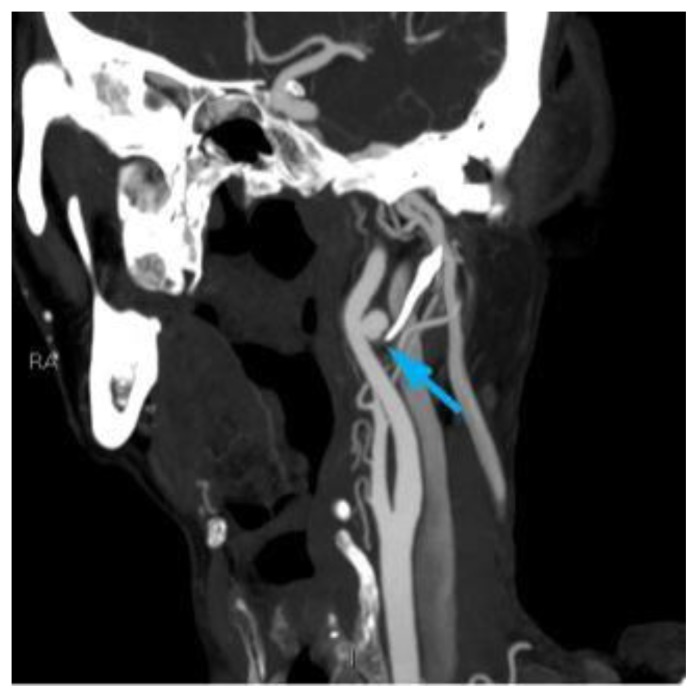

Figure 4.

85-year-old male with compression and a pseudoaneurysmal dilatation of the left ICA secondary to Eagle’s syndrome.

FINDINGS: Sagittal CTA of the neck demonstrates an 8 mm left ICA pseudoaneurysm with a thrombus. The tip of the elongated styloid process abutting the posterior aspect of the ICA (arrow) is also noted.

TECHNIQUE: Sagital CTA, 3 mm slice thickness using Visipaque (320 mgl/ml) injected at a rate of 5 ml/sec for a total volume of 65 ml

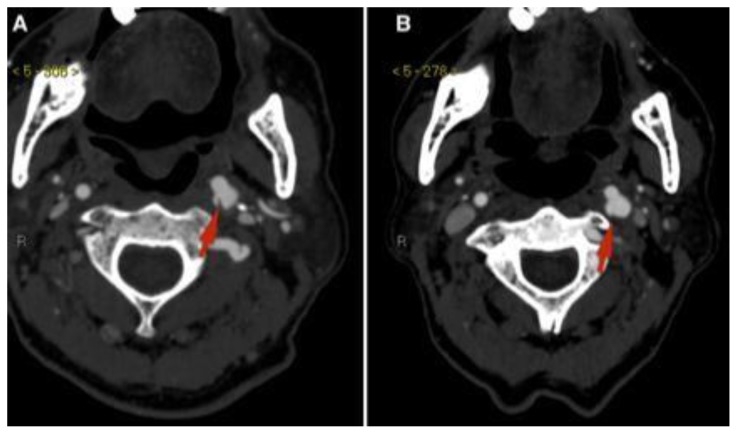

Figure 5.

85-year-old male with compression and a pseudoaneurysmal dilatation of the left ICA secondary to Eagle’s syndrome.

FINDINGS: Axial CTA of the neck demonstrates an 8 mm left ICA pseudoaneurysm with a thrombus (figure 5A) and the resolution of the thrombus one year later (figure 5B) pointed by the red arrows.

TECHNIQUE: Axial CTA, 3 mm slice thickness using Visipaque (320 mgl/ml) injected at a rate of 5 ml/sec for a total volume of 65 ml

Figure 6.

85-year-old male with thromboembolic infarction in the territory of the left MCA caused by a left ICA thromboembolism secondary to Eagle’s syndrome.

FINDINGS: Axial diffusion-weighted image (figure 6A) and axial apparent diffusion coefficient (figure 6B) 3T-MRI scan of the head demonstrating diffusion restriction suggesting infarction in the territory of the left MCA (arrows).

TECHNIQUE: Axial diffusion-weighted and apparent diffusion coefficient 3T-MRI of the head.

DISCUSSION

Etiology & Demographics

Watt Eagle, an American Otolaryngologist, first described Eagle’s Syndrome in the late 1930s [1–4]. Eagle’s Syndrome is the combination of either an elongated styloid process or calcified stylohyoid ligament with one of two symptom complexes [1–4]. It can be subdivided into the classical and carotid types. Approximately 4% of the population incidentally have a lengthened styloid process but are said to have Eagle’s Syndrome only if it causes classical or carotid type symptoms [5]. A normal styloid process is no longer than 3 cm. [5].

Clinical & Imaging Findings

In the classical subtype the extended styloid process compresses adjacent cranial nerves (namely CN V3, VII, IX, X, XII) causing dysphagia, odynophagia, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, dysphonia, ipsilateral anterior neck pain radiating to the face, or globus sensation [1,6,7]. In the carotid subtype the extended styloid compresses the internal or common carotid artery resulting in cerebral ischemic symptoms such as weakness, numbness, aphasia or visual changes [1,6,8]. While Carotid Eagle’s Syndrome is an uncommon cause of ischemic stroke it should be considered if ischemic symptoms vary with head position, if the styloid process is palpable in the tonsillar fossa or if palpation over the styloid process causes ischemic symptoms [6]. The elongated styloid process is visible on plain films but CT angiography is the gold standard for diagnosis as it allows for assessment of carotid artery and cranial nerve compression [9]. Conventional angiography can be used in cases where ischemic symptoms are positional or if the CT angiography is equivocal but Carotid Eagle’s syndrome is strongly suspected.

Treatment & Prognosis

In the classical subtype patients can be reassured that the syndrome is benign and pain can be managed with over-the-counter analgesics [10 – 12]. In the carotid subtype or in classical subtype with refractory symptoms, the elongated styloid process can be resected via either an intraoral or pharyngeal approach [10 – 12]. The intraoral approach requires ipsilateral tonsillectomy and carries the risk of retropharyngeal infection, airway edema and tenuous vascular control [10 – 12]. The pharyngeal approach carries the risk of injury to the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve [10 – 12]. As such most surgeons prefer a pharyngeal approach via an anterior sternocleidomastoid incision [5, 12].

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnosis of Eagle’s syndrome is broad and largely based on pathologies that can mimic its symptomatology. Pain located predominantly in the face and anterior neck may be secondary to third-molar impaction, arthritic degeneration of the cervical spine, or temporomandibular joint dysfunction; however, these conditions are unlikely to produce the other associated cranial nerve deficits that may be associated with classical Eagle’s syndrome [13]. Glossopharyngeal and trigeminal neuralgia may also present predominantly with odynophagia and facial pain, respectively [13]. In these cases, the pain tends to be sharp and stabbing in quality, rather than the dull, constant, pain reported by patients with classical Eagle’s syndrome [10 – 12]. Finally, tumors of the head and neck may produce a constellation of neck pain and lower cranial nerve dysfunction and should be considered in the differential for Eagle’s syndrome [13]. Positional cerebral ischemia, as seen in the first case, is virtually pathognomic for carotid Eagle syndrome [6].

Case Discussion

In both patients, the elongated styloid process came into contact with the internal carotid artery leading to symptomatic cerebral ischemia. In the first patient, the likely cause of ischemic symptoms was direct compression of the carotid artery by the elongated styloid process. The patient’s right-sided cerebral perfusion was entirely dependent on the right internal carotid artery because of the absent anterior and right posterior communicating arteries. As such, when the right internal carotid was compressed by the elongated styloid, hemodynamic right cerebral ischemia occurred resulting in left-sided symptoms (Figure 3). The patient declined surgical treatment, therefore, he was counselled regarding neck positioning and was followed-up with conservative treatment. In the second patient, the likely cause of ischemic stroke was embolization from pseudoaneurysmal thrombus as he had no evidence of cardiac disease and had very limited carotid atherosclerotic disease. The pulsations of the ICA along with the close relationship to the elongated styloid process probably led to repetitive micro-trauma to the ICA leading to the pseudoaneurysm formation with internal thrombus. The patient was managed medically with daily low dose Aspirin to prevent further ischemic events.

This patient had no new events while on Aspirin and one year imaging follow up showed resolution of the thrombus (Figure 5B).

TEACHING POINT

In an ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack without apparent cause, radiologists should make sure to look specifically at the styloid process on a CT head. In cases with an elongated styloid process or ossified stylohyoid ligament, Eagle’s Syndrome might be the cause of the stroke.

Table 1.

Summary table of Vascular Eagle’s Syndrome.

| Etiology | Unknown |

| Incidence | 4% of general population have elongated styloid process, 4% of those with elongated styloid process are symptomatic (classical or carotid type) |

| Gender ratio | 1:1 |

| Age predilection | Occurs most frequently in patients older than 40 |

| Risk factors | Prior Tonsillectomy, calcium metabolism disorders (ex. Chronic kidney disease), Trauma (8) |

| Treatment | Resection of elongated styloid process |

| Prognosis | Resection is curative |

| Imaging Findings | Plain Film – Elongated styloid process CT – Elongated styloid process +/− signs of vascular compression, pseudoaneurysm or nerve compression Conventional Angiography - +/− compression of carotid artery with head turning or pseudoaneurysm |

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis table for Vascular Eagle’s Syndrome.

| Differential Diagnosis | Radiography | CT | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eagle’s Syndrome |

|

|

|

| Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction |

|

|

|

| Third-molar impaction |

|

||

| Cervical spondylosis |

|

|

|

| Glossopharyngeal & Trigeminal neuralgias |

|

||

| Head & Neck neoplasm |

|

|

ABBREVIATIONS

- AComm

Anterior Communicating Artery

- CTA

CT Angiography

- ICA

Internal Carotid Artery

- MCA

Middle Cerebral Artery

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- PComm

Posterior Communicating Artery

REFERENCES

- 1.Eagle W. Symptomatic elongated styloid process; report of two cases of styloid process carotid artery syndrome with operation. Archives of otolaryngology. 1949;49:490–503. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1949.03760110046003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eagle W. Elongated styloid process: report of two cases. Archives of otolaryngology. 1937;25:584–87. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1937.00650010656008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eagle W. Elongated styloid process. Further observation and a new syndrome. Archives of otolaryngology. 1948;47:630–40. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1948.00690030654006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eagle W. Elongated styloid process; symptoms and treatment. Archives of otolaryngology. 1958;67:172–76. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1958.00730010178007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piagkou M, Anagnostopoulou S, Kouladouros K, Piagkos G. Eagle’s syndrome: a review of the literature. Clinical anatomy. 2009;22:545–558. doi: 10.1002/ca.20804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantinides F, Vidoni G, Bodin C, Di Lenarda R. Eagle’s syndrome: signs and symptoms. Journal of craniomandibular and sleep practice. 2013;1:56–60. doi: 10.1179/crn.2013.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aral IL KI, Gungor N. Eagle’s syndrome masquerading as pain of dental origin. Case report. Australian dental journal. 1997;42:18–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1997.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farhat HI, Elhammady MS, Ziayee H, Aziz-Sultan MA, Heros RC. Eagle syndrome as a cause of transient ischemic attacks. Journal of neurosurgery. 2009;110:90–3. doi: 10.3171/2008.3.17435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beder E OO, Karatayli OS, Anadolu Y. Three-dimensional computed tomography and surgical treatment for Eagle’s syndrome. Ear nose & throat journal. 2006;85:443–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chrcanovic BR, Custodio AL, de Oliveira DR. An intraoral surgical approach to the styloid process in eagle’s syndrome. Oral and maxiollofacial surgery. 2009;13:145–51. doi: 10.1007/s10006-009-0164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin TJ, Friedland DR, Merati AL. Transcervical resection of the styloid process in eagle syndrome. Ear nose & throat journal. 2008;87:399–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muderris T, Bercin S, Sevil E, Beton S, Kiris M. Surgical Management of elongated styloid process: intraoral versus transcervical. European archives of otolaryngology. 2014;271:1709–1713. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinheiro TG, Soares VY, Ferreira DB, Raymundo IT, Nascimento LA, Oliveira CA. Eagle’s Syndrome. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology. 2013;17(3):347–350. doi: 10.7162/S1809-977720130003000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]