Abstract

INTRODUCTION

To examine the risk of AD among cancer survivors in a national database.

METHODS

Retrospective cohort of 3,499,378 mostly male US veterans ≥65 followed 1996–2011. We used Cox models to estimate risk of AD and alternative outcomes (non-AD dementia, osteoarthritis, stroke and macular degeneration) in veterans with and without a history of cancer.

RESULTS

Survivors of a wide variety of cancers had modestly lower AD risk, but increased risk of the alternative outcomes. Survivors of screened cancers, including prostate cancer, had a slightly increased AD risk. Cancer treatment was independently associated with decreased AD risk; those who received chemotherapy had a lower risk than those who did not.

DISCUSSION

Survivors of some cancers have a lower risk of AD but not other age-related conditions, arguing that lower AD diagnosis is not simply due to bias. Cancer treatment may be associated with decreased risk of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, epidemiology, inverse association, risk, chemotherapy, radiation, cancer therapy, survival bias

1.1 Introduction

The unexpectedly low risk of most cancers in patients with Parkinson’s disease is well established,1 and converging evidence shows an inverse relationship between cancer and Alzheimer’s disease (AD).2–7 There are a number of biological pathways that explain why predisposition to one family of diseases might protect against the other.8–10 There is also molecular evidence that AD and cancers express the same genes but in opposite directions.11 A meta-analysis of five studies showed a 50% decreased risk of AD in patients with a history of cancer, and a 36% decreased risk of cancer in patients with AD.12 Two studies using administrative databases have been large enough to examine the relationship between AD and individual cancer types, 4, 5 and significant inverse associations were seen with hematologic malignancies, lung cancer and colorectal cancer.

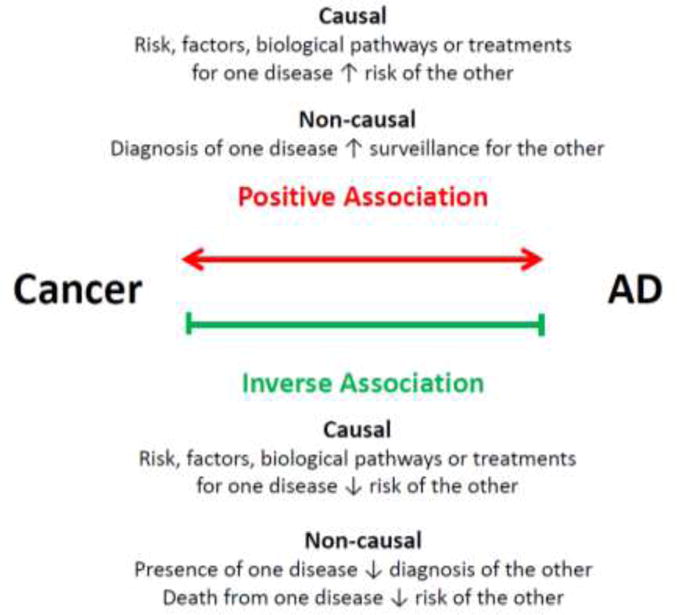

Untangling the relationship between chronic age-related conditions is fraught with bias. Patients with one disease may not live to get the other, and diagnosis with one serious condition may “mask” diagnosis with others. These factors do not seem to solely explain the relationship between cancer and AD, however, as decreased cancer risk is not seen in vascular dementia or stroke, other age-related conditions associated with impaired cognition and increased mortality.7 Furthermore, the lower risk of AD is found both in cancer survivors and non-survivors,3 and decreased risks of one disease are present both before and after diagnosis with the other.4 Nevertheless, the relation between these diseases is complex, and there is much to be discovered, including the role of cancer treatment.13 The most common hypotheses invoked to explain both positive and inverse associations between cancer and neurodegeneration are summarized in Figure 1. The Veterans Affairs (VA) clinical data, with detailed information on over five million US veterans, provides an opportunity to explore this relationship in greater depth.

Figure 1.

Hypotheses to explain epidemiologic associations between cancer and AD.

2.1 Methods

2.2 Study population

We assembled a retrospective cohort of veterans who received outpatient care between 1996 and 2011 in the US Veterans Affairs (VA) Healthcare System using national and regional patient care, healthcare utilization and claims databases. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the VA Boston Healthcare System with a waiver of informed consent.

Patients were eligible to enter the cohort if they were aged 65 or older and had been followed in the VA system for at least one year prior to study entry. We excluded veterans who had a diagnosis of any dementia defined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes (Table 1) or who received prescriptions for dementia-specific medications (galantamine, donepezil, rivastigmine, or memantine) any time prior to and including study baseline. ICD is a classification system of diagnostic codes used by clinicians to indicate the diagnoses relevant to each patient encounter. We required that patients have at least one visit to their primary care doctor in the year prior to study entry to be sure they were followed regularly in the VA.

Table 1.

Definition of exposure, outcomes and covariates

| Variable | ICD-9 codes |

|---|---|

| Cancer | 140–208, 238.6 |

| Any dementia | 290.0–290.3, 290.4–290.9, 291.2, 294.1, 294.11, 331.0–331.8, 331.9, 333.0, 333.4, 780.93, 797, 332.0, 294.8, 294.9, 438.0, 046.1, 046.3 |

| Non-AD dementia | 290.4–290.9, 291.2, 294.1, 294.11, 331.1–331.7, 331.82, 331.9, 333.0, 333.4, 780.93, 797, 332.0, 294.8, 294.9, 438.0, 046.1, 046.3, |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 331.0, 290.0, 290.2, 290.21, 290.3 |

| Stroke | 434.91, 434.11, 430, 431, 432.0–432.9, 434.01 |

| Osteoarthritis | 715.9 |

| Macular degeneration | 362.5 |

| Obesity | 278.0–278.9 |

| Hypertension | 401–405 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 272 |

| Diabetes | 250, 357.2, 362.01–362.07, 366.41 |

2.3 Exposure and Outcome

The exposure was diagnosis with cancer. Cancer was defined as having two or more codes for the same malignancy from a VA physician in order to avoid misclassification.14 We did not consider non-melanoma skin cancers in this analysis. The date of diagnosis was the first date the code was used in either an inpatient or outpatient encounter. To assess the validity of our cancer definition, we obtained data from the VA Central Cancer Registry (VACCR) on the most common cancers in our cohort: prostate, lung, colon, bladder and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The primary outcome for our analysis was a new diagnosis of AD. Patients were defined as having received an AD diagnosis if 1) an AD code was used in the outpatient setting by a primary care doctor, neurologist, neuropsychologist, geriatrician, or psychiatrist, and 2) there was no preceding code for another specific dementia (e.g. vascular dementia) or stroke. Alternative outcomes included non-AD dementia (any dementia that did not meet our definition for AD), stroke, osteoarthritis, and macular degeneration.

We defined the following known risk factors for dementia using ICD-9 codes documented for each participant prior to cohort entry: obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, coronary artery disease, and stroke. We used inpatient and outpatient CPT4 codes to identify patients who received chemotherapy and radiation.

2.4 Statistical Methods

We used Cox regression to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for the risk of subsequent AD and non-AD dementia in those with and without a history of specific cancers. We used cause-specific hazard models for analysis; thus the hazard ratios that we report are for risk among those still alive. We modeled cancer exposure and treatment as time-varying covariates. We used age in years as the timescale for the analysis. Patients were followed from entry age until they developed AD, died, or were lost to follow-up. To determine if there were substantial differences in the association between cancer and dementia by sex, we stratified the main analysis by sex. All analyses were adjusted for race (white, black, other, or unknown), cancer treatment (treatment with chemotherapy and/or radiation), dementia risk factors, years of follow-up in the VA prior to study entry and number of clinic visits in the year prior to study entry. To determine if the risk of AD after cancer diagnosis is similar to that of other age-related conditions, we repeated the main analysis with alternative outcomes. To explore the possibility of ascertainment bias, we calculated risks of AD and stroke over four intervals following cancer diagnosis (0–1 years, 1–2 years, 2–3 years, and >3 years). The reference group for each time interval was all members of the cohort of the same age who did not have a diagnosis of cancer. We repeated the main analysis using only registry-confirmed cases to assess the validity of our cancer definitions and adjust for cancer severity (clinical cancer stage and tumor grade). We considered a p value < 0.05 statistically significant. For analyses with many separate models, we corrected the threshold for statistical significance using the Bonferroni method. All analyses were conducted in SAS (version 9.2).

3.1 Results

Between 1996 and 2011, 3,499,378 veterans met inclusion criteria and contributed a total of 20,095,496.3 person-years at risk for AD. Of these, 771,285 (22%) were diagnosed with cancer. Baseline characteristics of veterans with and without cancer are displayed in Table 2. The population was predominantly white and only 1.9% were female (n=66,487). Veterans with a diagnosis of cancer had a similar median age to those without cancer, but had more non-cancer comorbidities (mean Charlson score 0.76 vs. 0.70; p<0.0001). They were more likely to be of black or unknown race and had substantially more visits to VA facilities in the year prior to entry. The most frequent cancers diagnosed were prostate (41.0%), lung (11.0%), colorectal (9.0%) and bladder (6.3%). Over a median of 5.7 years of follow-up (range 0.1–13.0), 285,735 veterans were given ICD-9 codes for non-AD dementia and 82,998 for AD.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of VA cohort by history of cancer at any time during follow-up (n=3,499,378)

| Characteristic | History of cancer (n =771,285) | No history of cancer (n=2,728,093) |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

|

| ||

| Median age, IQR | 71 (65,76) | 71 (65,77) |

|

| ||

| Male sex | 759,984 (98.6) | 2,669,695 (98.0) |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 547,372 (74.5) | 1,922,666 (70.5) |

| Black | 94,322 (12.2) | 182,268 (6.7) |

| Other | 5,790 (0.8) | 25,371 (0.9) |

| Unknown | 96,801 (12.6) | 587,788 (21.9) |

|

| ||

| Coronary artery disease | 211,296 (27.4) | 806,161 (29.6) |

|

| ||

| Hypertension | 533,943 (69.2) | 1,929,912 (70.7) |

|

| ||

| Diabetes | 205,233 (26.6) | 746,917 (27.4) |

|

| ||

| Stroke | 32,122 (4.2) | 110,514 (4.1) |

|

| ||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 355,939 (46.1) | 1,491,941 (54.7) |

|

| ||

| Obesity | 113,058 (14.7) | 418,995 (15.4) |

|

| ||

| Charlson Index | ||

| 0–1 | 639,252 (82.9) | 2,321,990 (85.1) |

| 2 | 84,487 (11.0) | 263,878 (9.7) |

| ≥3 | 47,546 (6.1) | 142,230 (5.2) |

|

| ||

| Median time (years) in VA prior to cohort entry (IQR) | 1.2 (1.1,2.0) | 1.3 (1.1,2.4) |

|

| ||

| ≥3 clinic visits in year prior to cohort entry | 529,890 (68.7) | 1,331,208 (48.8) |

Risks for diagnosis of any dementia and AD in male veterans with and without a prior cancer diagnosis are displayed in Table 3. There was no association between a history of all cancers combined and AD (HR=1.00). While prostate cancer was associated with a slightly increased AD risk (HR=1.08; 95%CI:1.04–1.11), the majority of tumor types were associated with decreased risk. This remained statistically significant after Bonferroni correction for lung cancer (HR=0.79; 95%CI=0.71–.89), lymphoma (HR=0.86; 95%CI=0.73–0.99) leukemia (HR=0.81;95%CI=0.68–0.97) and renal cancer (HR=0.79;95%CI:0.65–0.97). When we removed screened cancers, prostate, melanoma and colorectal, there was a significant inverse association between cancer and AD (HR=0.89;95%CI=0.88–0.90). There were no significant associations between cancer and AD among women veterans due to the much smaller sample size, but the patterns were similar, with screening-related cancers having an increased risk, and lung cancer a decreased risk (Table 4).

Table 3.

History of cancer and the risk of subsequent Alzheimer and non-Alzheimer dementia in a national cohort of male veterans (n=3,429,679)

| Number of cancer cases | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | At baseline | Incident cases | AD dementia (n=82,998) | Non AD dementia (n=285,735) |

| Any cancer (n=759,984) | 316,915 | 443,069 | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 1.17 (1.15–1.19)* |

| All cancers excluding prostate, colorectal and melanoma (n=346,194) | 122,277 | 223,917 | 0.89 (0.88–0.90)* | 1.21 (1.19–1.24)* |

| Prostate (n=315,262) | 154,405 | 160,857 | 1.08 (1.04–1.11)* | 1.09 (1.07–1.12)* |

| Lung (n=83,217) | 21,250 | 61,967 | 0.79 (0.71–.89)* | 1.29 (1.23–1.36)* |

| Colorectal (n=68,389) | 28,811 | 39,578 | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) | 1.08 (1.04–1.12)* |

| Bladder (n=48,576) | 19,273 | 29,303 | 1.01 (0.92–1.11) | 1.12 (1.06–1.17)* |

| Head and neck (n=36,440) | 17,898 | 18,542 | 0.91 (0.80–1.02) | 1.08 (1.02–1.14)* |

| Melanoma (n=30,139) | 11,422 | 18,717 | 1.11 (0.99–1.23) | 1.12 (1.06–1.18)* |

| Lymphoma (n= 25,949) | 11,329 | 14,620 | 0.86 (0.73–0.99)* | 1.11 (1.03–1.19)* |

| Leukemia (n=20,268) | 8,262 | 12,006 | 0.81 (0.68–0.97)* | 1.06 (0.98–1.15) |

| Renal (n=17,024) | 6,008 | 11,016 | 0.79 (0.65–0.97)* | 1.28 (1.18–1.39)* |

| Myeloma (n=9,452) | 3,572 | 5,880 | 0.80 (0.60–1.07) | 1.21 (1.07–1.36)* |

| Esophagus (n=9,123) | 2,453 | 6,670 | 0.74 (0.52–1.05) | 1.14 (0.98–1.32) |

| Pancreas (n=8,228) | 1,501 | 6,727 | 0.77 (0.51–1.14) | 1.25 (1.06–1.47)* |

| Liver (n=6,567) | 987 | 5,580 | 0.76 (0.46–1.23) | 1.45 (1.21–1.74)* |

| Stomach (n=6,111) | 1,681 | 4,430 | 0.86 (0.62–1.20) | 1.40 (1.22–1.61)* |

| Other (n=75,239) | 28,063 | 47,176 | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 1.27 (1.22–1.32)* |

Statistically significant associations. All analyses adjusted for number of clinic visits in year prior to baseline, follow-up time, cancer treatment, high cholesterol, hypertension, obesity, coronary arterial disease, diabetes, stroke, race. Confidence interval adjusted with Bonferroni correction. HR = Hazard Ratio; CI= confidence interval.

Table 4.

History of cancer and the risk of subsequent Alzheimer and non-Alzheimer dementia in a national veteran cohort of female veterans (n=66,487)

| Number of cancer cases | Hazard ratio (95% CI)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | At baseline | Incident cases | AD dementia (n=1,935) | Non AD dementia (n=5,755) |

| Any cancer (n=10,894) | 4,825 | 6,069 | 1.06 (0.93–1.21) | 1.14 (1.06–1.23)* |

| Non-screened cancers (n=5,642) | 2,213 | 3,429 | 0.96 (0.79–1.17) | 1.15 (1.04–1.27)* |

| Breast (n=3,782) | 1,998 | 1,784 | 1.14 (0.95–1.38) | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) |

| Lung (n=1,190) | 316 | 874 | 0.79 (0.45–1.40) | 1.36 (1.07–1.74)* |

| Colorectal (n=1,047) | 438 | 609 | 1.17 (0.83–1.63) | 1.30 (1.08–1.55)* |

| Other (n=4,875) | 2,073 | 2,802 | 0.97 (0.80–1.18) | 1.12 (0.96–1.31) |

Statistically significant associations. All analyses adjusted for number of clinic visits in year prior to baseline, follow-up time, cancer treatment, high cholesterol, hypertension, obesity, coronary arterial disease, diabetes, stroke, race. HR = Hazard Ratio; CI= confidence interval.

A sub-analysis in which we eliminated veterans with a history of cancer at baseline from the exposed cohort (data not shown) did not change the results substantially. In contrast to the inverse association seen between AD and many cancers, cancer history was uniformly associated with an increased risk of non-AD dementia, stroke, osteoarthritis and macular degeneration (Table 5).

Table 5.

History of cancer and the risk of non-dementia diagnoses in a national veteran cohort (N=3,499,378)

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer type | Stroke (n=214, 283) | Osteoarthritis (n=626,514) | Macular degeneration (n=365,430) |

| Any cancer | 1.34 (1.32–1.36) | 1.31 (1.29–1.32) | 1.37 (1.36–1.39) |

| Prostate | 1.08 (1.05–1.10) | 1.20 (1.18–1.21) | 1.16 (1.14–1.19) |

| Lung | 1.68 (1.61–1.76) | 1.42 (1.38–1.46) | 1.48 (1.42–1.53) |

| Colorectal | 1.21 (1.17–1.26) | 1.11 (1.08–1.14) | 1.23 (1.19–1.27) |

| Bladder | 1.35 (1.29–1.41) | 1.24 (1.20–1.28) | 1.41 (1.37–1.46) |

| Head and neck | 1.39 (1.32–1.47) | 1.18 (1.14–1.22) | 1.41 (1.35–1.47) |

| Melanoma | 1.25 (1.18–1.33) | 1.30 (1.25–1.34) | 1.43 (1.37–1.49) |

| Lymphoma | 1.18 (1.10–1.27) | 1.15 (1.10–1.20) | 1.17 (1.11–1.24) |

| Renal | 1.40 (1.29–1.52) | 1.38 (1.31–1.45) | 1.44 (1.35–1.53) |

Adjusted for sex, number of clinic visits in year prior to baseline, follow-up time, cancer treatment, high cholesterol, hypertension, obesity, coronary arterial disease, diabetes, stroke, race and confidence interval with Bonferroni Correction. Statistically significant associations are marked in bold.

We repeated the analysis in the 227,274 patients with the five registry-confirmed cancers and results did not change substantially, even after adjustment for cancer severity. The risk of AD was lower for those with stage 4 cancer (0.68; 95%CI 0.54–0.85) than for those with stages 2 (HR=0.82;95%CI 0.69–0.98) and 3 (HR=0.83; 95%CI:0.67–1.03). Patients who received cancer treatment were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with AD (HR=0.85;95%CI:0.79–0.92; Table 6). The effect was seen in those who received only chemotherapy, but not in those who received only radiation, compared to all others in the cohort. Cancer treatment did not decrease the risk of non-AD dementia or the alternative outcomes.

Table 6.

Subset analysis of the effect of cancer treatment on risk of subsequent Alzheimer and non-Alzheimer dementia among veterans with registry-confirmed cancer (n=227,274)*

| Treatment | AD cases n (%)

|

HR (95% CI) | Non-AD dementia cases, n (%)

|

HR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer treatment | Cancer treatment | |||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

|

| ||||||

| Any Treatment N=62,232 |

968 (1.6) |

4,010 (2.4) |

0.85 (0.79–0.92) | 4,278 (6.9) |

15,391 (9.3) |

1.00 (0.97–1.04) |

|

| ||||||

| Chemotherapy only N=22,217 |

347 (1.6) |

4,631 (2.3) |

0.80 (0.71–0.91) | 1,592 (7.2) |

18,077 (8.8) |

0.97 (0.91–1.02) |

|

| ||||||

| Radiation only N=31,909 |

553 (1.7) |

4,425 (2.3) |

0.98 (0.89–1.08) | 2,301 (7.2) |

17,368 (8.9) |

1.05 (1.01–1.10) |

Subset included all confirmed prostate, lung, colorectal, bladder cancers, and lymphoma

Adjusted for sex, cancer stage and grade, number of clinic visits in year prior to baseline, follow-up time, cancer treatment, high cholesterol, hypertension, obesity, coronary arterial disease, diabetes, stroke, and race. Statistically significant associations are marked in bold.

The risk of AD did appear to change as the time from cancer diagnosis increased in some cancers, but not in others (Supplemental Table 1). For prostate cancer and melanoma, AD risk was elevated for three years and then declined. The decreased risk of AD in patients with lung cancer was greatest in the year after cancer diagnosis but then remained lower than expected in all subsequent time periods, as it did in hematologic malignancies. The risk of stroke was highest in the year following cancer diagnosis and remained increased for the first three years (Supplemental Table 2). Although risks were lower in subsequent periods, they remained elevated in all subtypes except prostate and hematologic malignancies.

4.1 Discussion

In this retrospective cohort of 3.5 million elderly veterans, survivors of most cancers had a reduced risk of subsequent AD, while survivors of screening-related cancers had an increased risk. In contrast, survivors of all cancers had a higher risk of non-AD dementia, stroke, osteoarthritis and macular degeneration. These findings add to the existing evidence of an unusual epidemiologic association between neurodegenerative dementia and cancer.

In contrast to other studies, we did not find an inverse relationship between AD and overall cancer. This was largely driven by the higher risk of AD in survivors of prostate cancer, which accounted for 41% of malignancies in this mostly-male cohort, as opposed to 10.7% of cancer cases in the Northern Italian4 and 14.1% in the Cardiovascular Health Study.7 An analysis in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), found a measurable delay in AD onset in cancer survivors that was independent of APOE4 status; individuals diagnosed with multiple cancers had an even longer delay.15

The inverse relation between cancer and AD in our cohort is more modest than in others. This may be due in part to the high prevalence of cerebrovascular risk factors and cardiovascular disease in our population, as prior studies have shown a null or increased risk of AD in patients with vascular dementia and stroke.3, 7 Our results also likely differ due to our reliance on administrative data for the identification of dementia. In a number of other studies, incident AD was identified by population screening and rigorous evaluation by dementia experts.3, 7, 16 Diagnosis of AD in the clinical setting is more challenging than for stroke or cancer, which have a clear time of onset and for which definitive tests are available, leading to differences in detection and coding.

4.2 Consideration of survival and ascertainment bias

We found clear signs of survival bias in our analysis: malignancies with the worst prognosis had the lowest AD risk, and cancer appeared more “protective” in those with more advanced disease. This raises the issue of the competing risk of death. One group recently showed that accounting for competing risks eradicates the inverse association between cancer and AD.17 However, the decision about whether to account for competing risks depends on the question the analysis is trying to answer.18 When the goal is to measure the association between two diseases for the purpose of determining a causal relationship, then it is appropriate to ignore the competing risk, as is routinely done when using Cox models in an elderly cohort. Furthermore, if the inverse association between AD and many cancers is simply due to the competing risk of death, one would expect to see the same decreased risk of non-AD dementia and the other age-associated conditions. A SEER-Medicare study that examined the association between 400 disease pairings found many positive associations, but almost all inverse associations were between cancer and AD or PD.19 Together, this evidence supports a unique relationship between cancer and neurodegeneration.

It is intriguing that the cancers in which we observed a null or increased risk of AD are those for which early detection is common, and therefore have a better prognosis and are more likely to be diagnosed with other medical conditions (ascertainment bias). This may be particularly relevant in VA, which has effective cancer screening programs.20 In a study of dementia coding in VA, we found that dementia experts are much more likely to code for a specific diagnosis like AD than primary care providers.21 Patients with better prognoses may be more likely to be referred to a dementia specialist for further workup than those with more severe disease. We found that for prostate cancer and melanoma, the increased risk of AD was clustered in the few years after cancer diagnosis and did not persist over time. In contrast, people with lung cancer and hematologic malignancies had a decreased risk of AD that persisted throughout follow-up. It thus seems difficult to attribute these associations to ascertainment bias. We note that an increased risk of cancers for which early detection is possible is also seen in PD (melanoma, breast, and thyroid cancers) despite the overall inverse association.1, 22

4.3 Strengths and limitations

Given the large size of our overall cohort, we had adequate power to explore the relationship between many individual types of cancer and cancer treatment and subsequent AD. We were able to control for multiple potential confounders and assess alternative outcomes. We were also able to look at the way in which cancer treatment modifies the relationship between cancer and AD. A number of limitations should be considered when interpreting our results. First, there is substantial under-diagnosis of dementia in this clinical database; thus, we were not able to eliminate all prevalent cases of dementia at baseline. Our exposure, primary and secondary outcomes, and potential confounders were derived from diagnostic codes. We have previously shown that about 30% of patients with dementia in the VA are given only non-specific dementia codes, and that a substantial number of these meet criteria for AD on chart review. Thus, there is likely substantial misclassification of dementia in our cohort. However, we have already shown that the inverse association between AD and cancer is present in a cohort with exquisite definition of both diseases.3 A final limitation is the fact that we did not have linked Medicare data and thus had no information on cancers that were diagnosed and treated outside of the VA.

5 Cancer treatment and AD risk

Cancer treatment was associated with a lower risk of AD but an increased risk of the alternative outcomes; patients who received only chemotherapy had a lower risk than those who received only radiation. Chemotherapy might serve as a marker of cancer severity, denoting poorer survival or decreased detection of other diseases; however, it did not confer a lower risk of the alternative outcomes, suggesting a special relationship with AD. Another possibility is that cancer therapy somehow decreases AD risk. Commonly used drugs like taxanes stabilize microtubules and lead to clinical improvement in mouse models of AD,23, 24 while anthracyclines can dissolve tangles.25 A number of targeted cancer therapies are currently being studied for AD, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors26 and retanoid X receptors.27 However, because a number of studies suggest that some cancer therapy may worsen cognition, 28, 29 30 a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms is needed before launching into clinical trials of repurposed oncology drugs.

Epidemiologic studies can at best generate hypotheses about causal relationships and will always be limited by bias and confounding factors. A deeper approach is required, such as that taken by a recent study using the ADNI cohort that examined the association of cancer and neuroimaging biomarkers, and found no evidence of increased grey matter density in regions associated with AD.15 Regardless of epidemiologic observations, investigation of the substantial genetic and biological overlap between AD and cancer is already yielding insights into the pathophysiology, treatment and prevention of both diseases, and should become an active area of research. Comparative systems biology may be a particularly appropriate method to further unravel this mystery.31

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by VA Merit Review Award I01CX000934-01A1 (Driver).David Swanson was supported by NIH T32 NS048005. Rebecca Betensky was funded in part by the Harvard NeuroDiscovery Center and the Harvard Catalyst (NIH UL1 TR001102).

References

- 1.Bajaj A, Driver JA, Schernhammer ES. Parkinson’s disease and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:697–707. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catala-Lopez F, Suarez-Pinilla M, Suarez-Pinilla P, et al. Inverse and direct cancer comorbidity in people with central nervous system disorders: a meta-analysis of cancer incidence in 577,013 participants of 50 observational studies. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2014;83:89–105. doi: 10.1159/000356498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Driver JA, Beiser A, Au R, et al. Inverse association between cancer and Alzheimer’s disease: results from the Framingham Study. BMJ. 2012;344:e1442. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Musicco M, Adorni F, Di Santo S, et al. Inverse occurrence of cancer and Alzheimer disease: a population-based incidence study. Neurology. 2013;81:322–328. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829c5ec1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ou SM, Lee YJ, Hu YW, et al. Does Alzheimer’s disease protect against cancers? A nationwide population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2013;40:42–49. doi: 10.1159/000341411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roe CM, Behrens MI, Xiong C, Miller JP, Morris JC. Alzheimer disease and cancer. Neurology. 2005;64:895–898. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152889.94785.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roe CM, Fitzpatrick AL, Xiong C, et al. Cancer linked to Alzheimer disease but not vascular dementia. Neurology. 2010;74:106–112. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c91873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behrens MI, Lendon C, Roe CM. A common biological mechanism in cancer and Alzheimer’s disease? Current Alzheimer research. 2009;6:196–204. doi: 10.2174/156720509788486608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driver JA. Understanding the link between cancer and neurodegeneration. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2012;3:58–67. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tabares-Seisdedos R, Rubenstein JL. Inverse cancer comorbidity: a serendipitous opportunity to gain insight into CNS disorders. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2013;14:293–304. doi: 10.1038/nrn3464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibanez K, Boullosa C, Tabares-Seisdedos R, Baudot A, Valencia A. Molecular evidence for the inverse comorbidity between central nervous system disorders and cancers detected by transcriptomic meta-analyses. PLoS genetics. 2014;10:e1004173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catala-Lopez F, Crespo-Facorro B, Vieta E, Valderas JM, Valencia A, Tabares-Seisdedos R. Alzheimer’s disease and cancer: current epidemiological evidence for a mutual protection. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42:121–122. doi: 10.1159/000355899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganguli M. Cancer and Dementia: It’s Complicated. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2015;29:177–182. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farwell WR, Scranton RE, Lawler EV, et al. The association between statins and cancer incidence in a veterans population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:134–139. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nudelman KN, Risacher SL, West JD, et al. Association of cancer history with Alzheimer’s disease onset and structural brain changes. Frontiers in physiology. 2014;5:423. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White RS, Lipton RB, Hall CB, Steinerman JR. Nonmelanoma skin cancer is associated with reduced Alzheimer disease risk. Neurology. 2013;80:1966–1972. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182941990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanson HA, Horn KP, Rasmussen KM, Hoffman JM, Smith KR. Is Cancer Protective for Subsequent Alzheimer’s Disease Risk? Evidence From the Utah Population Database. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2016 doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pintilie M. Analysing and interpreting competing risk data. Stat Med. 2007;26:1360–1367. doi: 10.1002/sim.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Ukraintseva S, Arbeev K, Kulminski A, Yashin AI. Morbidity risks among older adults with pre-existing age-related diseases. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48:1395–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long MD, Lance T, Robertson D, Kahwati L, Kinsinger L, Fisher DA. Colorectal cancer testing in the national Veterans Health Administration. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2012;57:288–293. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butler D, Kowall NW, Lawler E, Michael Gaziano J, Driver JA. Underuse of diagnostic codes for specific dementias in the Veterans Affairs New England healthcare system. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:910–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rugbjerg K, Friis S, Lassen CF, Ritz B, Olsen JH. Malignant melanoma, breast cancer and other cancers in patients with Parkinson’s disease. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2012;131:1904–1911. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishihara T, Hong M, Zhang B, et al. Age-dependent emergence and progression of a tauopathy in transgenic mice overexpressing the shortest human tau isoform. Neuron. 1999;24:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang B, Maiti A, Shively S, et al. Microtubule-binding drugs offset tau sequestration by stabilizing microtubules and reversing fast axonal transport deficits in a tauopathy model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:227–231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406361102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pickhardt M, Gazova Z, von Bergen M, et al. Anthraquinones inhibit tau aggregation and dissolve Alzheimer’s paired helical filaments in vitro and in cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3628–3635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410984200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufman AC, Salazar SV, Haas LT, et al. Fyn inhibition rescues established memory and synapse loss in Alzheimer mice. Annals of neurology. 2015;77:953–971. doi: 10.1002/ana.24394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cramer PE, Cirrito JR, Wesson DW, et al. ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models. Science. 2012;335:1503–1506. doi: 10.1126/science.1217697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahles TA, Root JC, Ryan EL. Cancer- and cancer treatment-associated cognitive change: an update on the state of the science. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30:3675–3686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald BC, Conroy SK, Ahles TA, West JD, Saykin AJ. Gray matter reduction associated with systemic chemotherapy for breast cancer: a prospective MRI study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:819–828. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1088-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee PE, Tierney MC, Wu W, Pritchard KI, Rochon PA. Endocrine treatment-associated cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors: evidence from published studies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158:407–420. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3906-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saykin AJ, Shen L, Yao X, et al. Genetic studies of quantitative MCI and AD phenotypes in ADNI: Progress, opportunities, and plans. Alzheimer’s & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2015;11:792–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.