Abstract

Objective: To investigate the correlation between changes of contralesional cortical excitability evaluated by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and functional recovery in patients with hemiparetic stroke. Methods: Eight inpatients (mean age: 75.9±13.8 years) with mild to moderate hemiparesis were enrolled. TMS was delivered to the optimal scalp position over the contralesional (ipsilateral to the paresis) primary motor cortex (M1) to activate the unaffected flexor carpi radialis muscle (FCR) while the patient picked up a wooden block with the affected hand. The amplitude of the motor-evoked potential (MEP) was measured and then was divided by the resting MEP amplitude (MEP ratio). For evaluation of motor function, we tested grip strength (GS), performed the upper extremity motor section of the Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA-UE), and performed the Purdue Pegboard Test (PPT) when the patients were admitted to our hospital (T1) and 2 months after admission (T2). Results: The MEP ratio was significantly decreased at the second examination. The partial correlations between the MEP ratio and FMA-UE at T1, and PPT of an affected hand at T2 were observed while controlling for the period after stroke onset as the confounding variable. Conclusion: The reduction of contralesional cortical hyperactivity is related to the functional recovery in part, but not related with the period after stroke onset. This suggests that enhanced reduction of contralesional M1 hyperactivity contributes to functional recovery after stroke.

Keywords: Motor evoked potential, motor recovery, stroke

It has been reported that excitability of both the ipsilesional and/or contralesional motor cortex shows physiological plasticity during functional recovery after stroke1-4). Marshall et al.1) investigated the longitudinal course up to 6 months of cerebral motor activation induced by finger movement task during post-stroke recovery by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) activation. They showed an evolution in the sensorimotor cortical activation from an early (20 days after stroke) contralesional hyperactivation to a later (4 months after stroke) ipsilesional hyperactivation concomitant to recovery. This result suggests that a dynamic bihemispheric reorganization of motor networks occurs during the recovery process. Other functional brain imaging studies have also identified such time-dependent cortical plastic activities during the re-acquisition of motor function2-4). Although these imaging studies clearly show that cortical excitability changes during the recovery process and contribute to the function recovery after stroke, less attention has been paid to the enhanced activity of contralesional motor cortex that is observed during early phase after the onset of stroke.

Although Traversa et al.5) observed a longitudinally increased amplitude of ipsilesional relaxed motor evoked potential (MEP), they did not observe the changes in contralesional MEP amplitude along with functional recovery that was detected in brain imaging studies. On the other hand, the paired-pulse TMS studies that induced contralesional intracortical inhibition (ICI) showed increased excitability of contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) in stroke patients6-8). With regard to neuronal hyperactivity in the contralesional motor cortex after stroke, there are several possible mechanisms such as the reduced interhemispheric inhibition (IHI) by the ipsilesional cortex6) or the mirror movements observed in the unaffected side9). In other words, these also suggest that stroke induced contralesional cortical hyperactivity, as a consequence, may excessively inhibit ipsilesional cortical activity. Thus, we hypothesized that the enhanced contralesional activity might be the possible disturbance for the early motor recovery of the affected side. The contralesional cortical excitability during the motor task by an affected side may reflect the extent of the inhibitory modulation from contralesional to ipsilesional cortex. Therefore, we examined longitudinally contralesional cortical activity while stroke patients were performing volitional hand motor task by an affected side, and measured motor function of the upper extremity, then finally evaluated the correlation between contralesional cortical excitability and an affected side motor function. The significant correlation may reveal the novel therapeutic approach to enhance post-stroke functional recovery in the field of rehabilitation.

Methods

Subjects

Eight stroke patients (2 men and 6 women with a mean age of 75.9±13.8 years) with subacute or chronic and mild to moderate hemiparesis participated in this study (Table 1). Inclusion criteria were 1) unilateral stroke involving the corticospinal tract; 2) less than 4 months after the first stroke event; and 3) a mild-moderate upper limb motor deficit with the score of Fugl-Meyer Assessment (FMA-UE) >2110,11). All the subjects were able to pick object up by an affected hand. According to the international guideline12), we excluded patients who have a history of induced seizures or epilepsy and major head trauma, as well as patients with metal in the skull, cranial cavity or a cardiac pacemaker. All subjects gave written consent to participation, and the study was performed with approval from the ethics committee of Daisen Rehabilitation Hospital and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of stroke patients on admission

| Patient no. | Age | Sex | Days post-stroke | Paretic side | Type of stroke | Stroke location | FMA-UE | PPT (total # of peg) | GS (kg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U | A | U | A | ||||||||

| FMA, Fugl-Meyer Assessment; PPT, Perdue Pegboard Test; UE, upper extremity; U, unaffected side; A, affected side | |||||||||||

| 1 | 78 | F | 48 | L | Ischemic | Medulla oblongata | 64 | 13 | 11 | 22.4 | 6.8 |

| 2 | 48 | F | 34 | R | Ischemic | Corona radiata | 36 | 13 | 0 | 27.8 | 3.6 |

| 3 | 63 | F | 96 | R | Hemorrhagic | Thalamus | 36 | 12 | 0 | 27.8 | 4.2 |

| 4 | 85 | F | 119 | L | Hemorrhagic | Basal ganglia | 53 | 9 | 4 | 8.3 | 3.9 |

| 5 | 88 | M | 36 | L | Ischemic | Parietal | 61 | 10 | 8 | 21.6 | 20.6 |

| 6 | 76 | M | 47 | R | Hemorrhagic | Temporofrontal | 63 | 7 | 5 | 30.6 | 18.6 |

| 7 | 86 | F | 15 | R | Ischemic | Corona radiata | 52 | 4 | 2 | 13.4 | 9.6 |

| 8 | 83 | F | 18 | R | Hemorrhagic | Basal ganglia | 54 | 5 | 5 | 13.6 | 15.5 |

| Mean | 75.9 | 51.6 | 52.4 | 9.1 | 4.4 | 20.7 | 10.4 | ||||

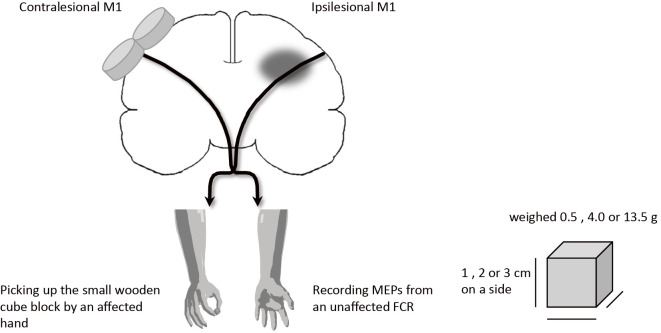

Experimental Procedures

TMS was delivered to the optimal scalp position over the contralesional motor cortex for activation of the unaffected flexor carpi radialis muscle (FCR) while the patient picked up a small wooden cube in the affected hand and the resting motor threshold (MT) was measured. Although FCR is a muscle that mainly acts to flex and abduct the hand, the stroke patients often achieve the picking object up task by an affected hand with recruitment of this muscle activity. The cube block consisted of 1, 2 or 3 cm on a side and its weight was 0.5, 4.0 or 13.5 g, respectively (Fig. 1). The block was small enough that it did not cause an increase in the background EMG activity of the unaffected FCR. The background EMG activity was measured as integrated EMG for the 1.0 second before and during picking up a cube block. Electrical signals were recorded from the unaffected FCR muscle by using bipolar surface electrodes placed longitudinally over the muscle on cleaned skin, with a reference electrode placed distal to the medial epicondyle (Ag-AgCl, 5 mm in diameter, interelectrode distance of 20 mm). EMG signals were amplified (500-1,000 x), filtered with a band-pass filter (10-500 Hz), sampled at 1 K Hz (PowerLab, USA), and analyzed on a personal computer.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the experimental setup.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

TMS was performed with a 70 mm figure-of-eight coil connected to a MagStim200 stimulator (Magstim, UK). The coil was placed over the contralesional motor cortex at the optimal location to elicit the best motor response in the unaffected FCR muscle. MT was defined as the minimum stimulus intensity that induced a reliable MEP of 50 μV at rest in at least five out of 10 responses13). The MEP was recorded at 110% of resting MT14) in consideration of patient burden and 10 trials were collected except for the failed picking cube up. Peak to peak MEP amplitude was measured and averaged, and then it was divided by the MEP amplitude obtained at rest to calculate the MEP ratio.

Motor Function Test

Motor function of the upper extremity was evaluated by using the FMA-UE, by performing the Purdue pegboard test (PPT), and by assessing grip strength (GS). To estimate hand dexterity, the PPT assesses the total number of pegs replaced in a pegboard during 30 seconds for each hand15). A digital hand dynamometer was used to measure hand grip power. These tests were done when the patients were admitted to our hospital (T1) and 2 months later (T2).

Statistical analysis

Values are shown as mean±standard deviations (SD). Average values of each variable were compared by using the paired t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The relationships between MEP ratio and each of motor function tests (GS, FMA-UE, and PPT) at T1 and T2 in both sides were examined by calculating partial correlation coefficients while controlling for the period after stroke onset as the confounding variable. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

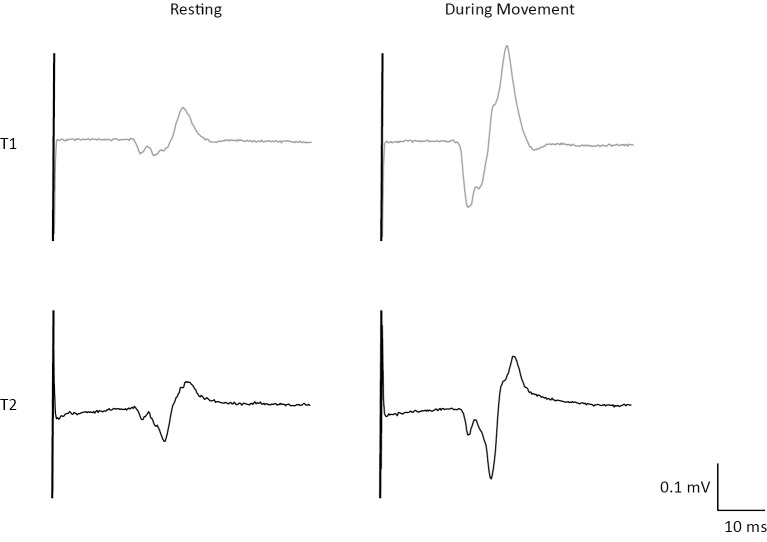

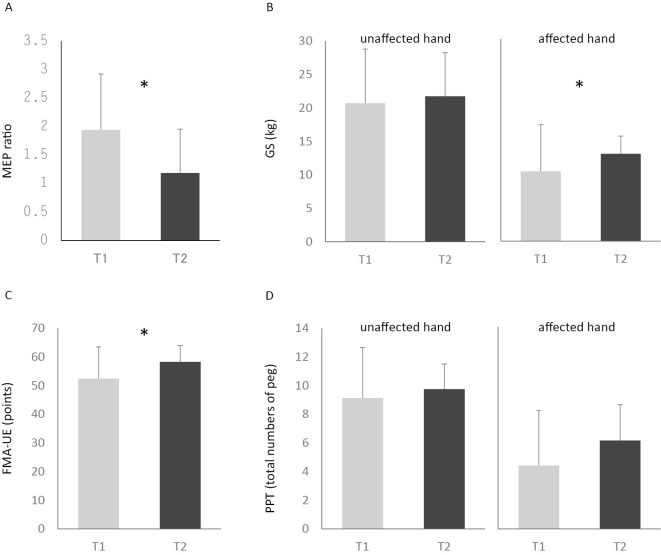

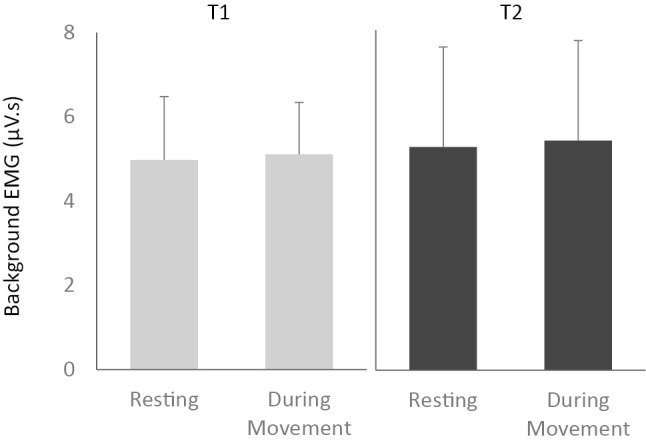

The period from stroke onset to T1 was 51.6±37.0 days and that to T2 was 104.6±48.1 days. There was no significant difference of unaffected side EMG activity between that at rest and that when the patient picked up the block with the affected hand (T1: p=0.44, T2: p=0.87, Fig. 2). The stimulator outputs for the resting MT were 49.6 ±11.8 % at T1 and 50.3±9.8 % at T2, respectively. Although the resting MEP did not change significantly (0.11±0.04 at T1 vs. 0.14±0.07 mV at T2), the MEP amplitudes during the task were 0.2±0.08 mV at T1 and 0.14±0.1 mV at T2, and the MEP ratio decreased significantly from 1.94±0.99 at T1 to 1.19±0.77 at T2 (p<0.05, Fig. 3 and 4 A). The GS of the affected hand increased from 10.35±6.95 kg at T1 to 12.96±7.45 kg at T2 and the FMA-UE score also increased from 52.4±11.1 to 58.3±5.7, respectively. Both of these scores showed significant improvement (GS: p<0.05, FMA-UE: p<0.05, Fig. 4 B and C), however there was no significant difference in PPT between T1 (4.4±3.8) and T2 (6.1±2.5) (p=0.07).

Figure 2.

Background EMG of the unaffected FCR at rest and while picking up a wooden cube with the affected hand at T1 (gray bar) and T2 (black bar).

Figure 3.

Representative examples of raw MEP data trace from the FCR muscle in one subject. Traces show the resting MEP and the MEP during movement of affected hand at T1 (gray) and T2 (black).

Figure 4.

A: Averaged MEP ratio during movement of the affected hand at T1 (gray bar) and T2 (black bar): *p< 0.05. B-D: Results of motor function at T1 (gray bar) and T2 (black bar): *p<0.05.

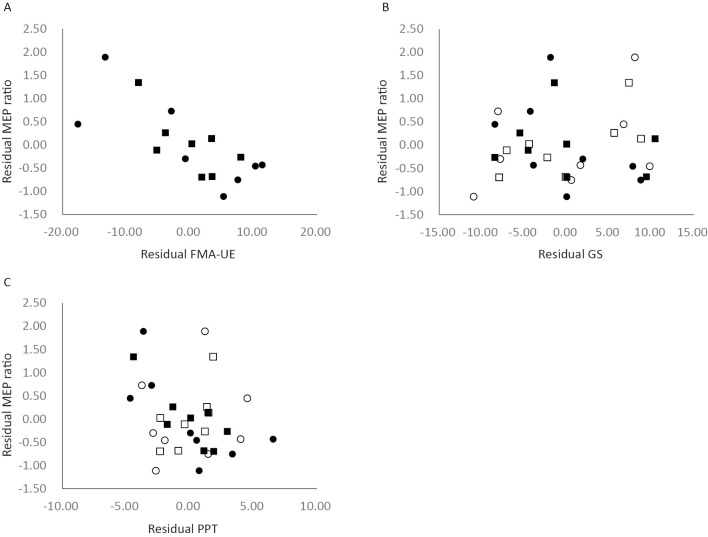

The partial correlation between the MEP ratio and FMA-UE was significant at T1, but not at T2 (FMA-UE at T1: r=-0.765, 95% CI -0.96 to -0.13, p<0.05, FMA-UE at T2: r=-0.69, 95% CI -0.94 to 0.03, p=0.09, Fig. 5 A). We also observed significant correlation between MEP ratio and PPT of an affected hand at T2 (PPT at T1: r=-0.689, 95% CI -0.94 to 0.03 p=0.09, PPT at T2: r=-0.81, 95% CI -0.96 to -0.24, p<0.05, Fig. 5 C). However, there were no significant correlations between MEP ratio and both GS and unaffected PPT (Fig. 5 B, C).

Figure 5.

Plot showing the partial correlation between the MEP ratio and motor function tests controlling for the period after stroke onset (A-C): black circles (T1) and squares (T2), affected hand; white circles (T1) and squares (T2), unaffected hand.

Discussion

1. Changes of contralesional cortical activity and function after stroke

TMS has been used as a noninvasive method to investigate motor cortical activity and its reorganization after stroke. Reorganization of motor circuits in the cerebral cortex is thought to contribute to the functional recovery. In this study, we had evaluated the relationship between contralesional cortical activity and affected side motor function. We found that the MEP ratio was significantly decreased at T2, along with improvement of affected side motor function except for PPT. The decrease of the MEP ratio at T2 suggests that activity of the contralesional motor cortex decreased over the 2-month period after admission. In other words, contralesional motor cortical activity was higher at T1 than at T2. Contralesional cortical hyperactivity after stroke was previously described in humans and was found to decrease throughout the recovery period5,14). There are also many brain activation studies those showed the time-dependent cortical plastic activities during motor function recovery1-4). For example, Tombari et al.2) investigated the longitudinal changes of hand motor cortical activation patterns in stroke patients (20 days, 4 months, and 12 months after stroke) by fMRI, and reported that early bilateral primary sensorimotor cortical hyperactivity was transient and that the level of activity finally converged with that of the ipsilesional sensorimotor cortex by 1 year after the stroke. A near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) study also showed that movement of the affected hand activated the bilateral sensorimotor cortices soon after stroke (<25 days from the onset), whereas the pattern of activation returned toward normal at a later period (>35 days)3). From these studies, it might be possible that a transiently observed motor cortical hyperactivation in the contralesional hemisphere plays as a trigger for the post stroke neural reorganization followed by functional recovery. In this study, we found significant partial correlations, controlling by the period after onset, between the MEP ratio and FMA-UE at T1, and PPT at T2, but no correlation between the MEP ratio and GS. All of these results suggest that reduction of contralesional cortical hyperactivity is related to the functional recovery in part, but not related to the period after stroke. It was interesting that the motor recovery was not achieved in parallel even when the MEP ratio was decreased. Further studies are necessary for better understanding how the changes in MEP amplitude after stroke affect the performance of different type motor task.

2. Contralesional cortical hyperactivity and the possible neuronal mechanism

In this study, although resting MEP did not change significantly between T1 and T2, MEP during motor task which was normalized to resting MEP decreased at T2. Same as us, the study that recorded resting MEP of contralesional hemisphere with the stimulus intensity of 110% MT did not show significant change up to about 4 months after the onset5). Manganotti et al.7) also reported that no significant difference in MEP amplitude at single TMS (120% MT) was observed between 5-7 days and 30 days after stroke in the unaffected hemisphere, but they further indicated that contralesional intracortical inhibition (ICI) by paired-pulse TMS returned to normal values later in good function recovery group. These results indicate that the resting MEP may not be a sufficient indicator for the evaluation in which contralesional cortical activity is related to the affected side motor functional recovery, and changes in motor disinhibition on the unaffected side might be related to motor recovery8). Therefore, in this study, it is appropriate to measure contralesional MEP during affected hand motor task.

Mirror movements those observed during volitional motor behavior by affected side are characteristic in patients with hemiplegic stroke and are supposed to reflect some aspects of the recovery process16-18). However, this neural mechanism is not clearly understood. Tsuboi et al.19) reported that reduction of commissural inhibition from the ipsilesional side might be a possible mechanism underlying mirror movements. Although activation of the contralesional motor cortex seems to be correlated with the severity of mirror movements20), we observed enhanced contralesional cortical activity without unaffected hand mirror movement-like accompanying movements at T1. Excessive IHI from the contralesional to ipsilesional hemisphere during voluntary movement of the affected hand could have an adverse influence on motor recovery21), so persistent hyperactivity of the contralesional motor cortex would delay the recovery of motor function.

3. Clinical implications

This study showed that the functional improvement was related to the decrease of the MEP ratio in the contralesional hemisphere. This indicates that the downregulation or normalization of contralesional cortical hyperexcitability that observed early phase after stroke might be a reasonable approach to cure motor deficits. Repetitive TMS (rTMS) is a noninvasive method of suppressing or facilitating cortical activity. For example, applying 1 Hz low-frequency rTMS to the motor cortex can induce downregulation of cortical activity with modification of cortical synaptic efficiency22). In addition, it has been shown that applying low-frequency rTMS to the contralesional hemisphere can improve motor function of the affected upper limb in patients with acute23) and chronic stroke24,25). However, the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying such functional recovery are not well understood. One plausible mechanism is correction of an imbalance of cortical excitability between two hemispheres23). Matsuura et al.26) recently showed that application of inhibitory rTMS to the contralesional motor cortex facilitates functional recovery of paretic limbs in acute stroke patients by enhancing paretic movement-related neural activity in the ipsilesional motor area. It is also suggested that the transcranial direct current stimulation is a powerful tool to inhibit cortical excitability27,28). Further investigations will be required to better understand the mechanism of cortical sensorimotor network repair to enhance motor recovery after stroke and to establish novel methods for enhancing the outcome with these tools.

4. Study limitations

Previous study reported that the evolution of intracortical excitability may vary between patients with different lesion site6,8) and clinical characteristics29). In this sense, the first limitation of the present study was its small sample size. However, we were able to show the clear statistical significance of differences in the variables examined, including the MEP ratio on the contralesional side. Although the PPT did not show the statistically significant improvement at T2, we observed a significant correlation between changes of the MEP ratio and PPT of the affected hand. This contradictory result might be due to that PPT is the task that requires more fine dexterity than that in GS or FMA-UE and this assumes influence on the results between subjects those show the different extent of motor functional recovery. Also, clinical characteristics of the subjects such as the type and location of stroke varied in this study, but our inclusion criteria were strictly applied and the results were thought to be consistent. The second limitation is which muscle is the most appropriate to record MEP for the present task in our subjects. Further studies are necessary in order to determine the muscle that allows us to record MEP constantly in stroke hemiplegic patients. In addition, because it is reported that MEP amplitude increases with increasing stimulation intensity30), we may need to consider the stimulation intensity we used in this study is appropriate. Finally, we could not determine the extent of individual training performed by each subject during the study period, except for a daily session with the physical therapist. Therefore, we would need to accurately monitor the quality and quantity of personal training in a future study to evaluate its influence on contralesional motor activity.

Conclusion

The MEP ratio for contralateral M1 was significantly correlated with affected side motor function, suggesting that decreased activity of contralesional M1 contributes to functional recovery. Therefore, suppression of hyperactivity in the contralesional motor cortex may be the key to enhancing functional recovery after stroke.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Masahiro Tomita (Director of Daisen Rehabilitation Hospital) and the staff of our department for their support and helpful comments. This study was supported by a research grants from the Japanese Physical Therapy Association to AM and MEXT KAKENHI Grant Number 17075002 to FM.

References

- 1. Marshall RS, M Perera G, et al.: Evolution of cortical activation during recovery from corticospinal tract infarction. Stroke. 2000; 31: 656-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tombari D, Loubinoux I, et al.: A longitudinal fMRI study: in recovering and then in clinically stable sub-cortical stroke patients. Neuroimage. 2004; 23: 827-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takeda K, Gomi Y, et al.: Shift of motor activation areas during recovery from hemiparesis after cerebral infarction: a longitudinal study with near-infrared spectroscopy. Neurosci Res. 2007; 59: 136-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Calautti C, Leroy F, et al.: Displacement of primary sensorimotor cortex activation after subcortical stroke: a longitudinal PET study with clinical correlation. Neuroimage. 2003; 19: 1650-1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Traversa R, Cicinelli P, et al.: Neurophysiological follow-up of motor cortical output in stroke patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000; 111: 1695-1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shimizu T, Hosaki A, et al.: Motor cortical disinhibition in the unaffected hemisphere after unilateral cortical stroke. Brain. 2002; 125: 1896-1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manganotti P, Patuzzo S, et al.: Motor disinhibition in affected and unaffected hemisphere in the early period of recovery after stroke. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002; 113: 936-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bütefisch CM, Wessling M, et al.: Relationship between interhemispheric inhibition and motor cortex excitability in subacute stroke patients. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008; 22: 4-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wittenberg GF, Bastian AJ, et al.: Mirror movements complicate interpretation of cerebral activation changes during recovery from subcortical infarction. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2000; 14: 213-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fugl-Meyer AR, Jääskö L, et al.: The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1975; 7: 13-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Velozo CA and Woodbury ML: Translating measurement findings into rehabilitation practice: an example using Fugl-Meyer Assessment-Upper Extremity with patients following stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011; 48: 1211-1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rossi S, Hallett M, et al.; The Safety of TMS Consensus Group: Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009; 120: 2008-2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rossini PM, Barker AT, et al.: Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994; 91: 79-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Traversa R, Cicinelli P, et al.: Follow-up of interhemispheric differences of motor evoked potentials from the ‘affected' and ‘unaffected' hemispheres in human stroke. Brain Res. 1998; 803: 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tiffin J and Asher EJ: The Purdue pegboard; norms and studies of reliability and validity. J Appl Psychol. 1948; 32: 234-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nelles G, Cramer SC, et al.: Quantitative assessment of mirror movements after stroke. Stroke. 1998; 29: 1182-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Formisano R, Pantano P, et al.: Late motor recovery is influenced by muscle tone changes after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005; 86: 308-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu D, Qian L, et al.: Effects on decreasing upper-limb poststroke muscle tone using transcranial direct current stimulation: a randomized sham-controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013; 9: 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tsuboi F, Nishimura Y, et al.: Neuronal mechanism of mirror movements caused by dysfunction of the motor cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2010; 32: 1397-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim Y-H, Jang SH, et al.: Bilateral primary sensori-motor cortex activation of post-stroke mirror movements: an fMRI study. Neuroreport. 2003; 14: 1329-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murase N, Duque J, et al.: Influence of interhemispheric interactions on motor function in chronic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2004; 55: 400-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maeda F, Keenan JP, et al.: Modulation of corticospinal excitability by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000; 111: 800-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khedr EM, Adbel-Fadeil MR, et al.: Role of 1 and 3 Hz repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor function recovery after acute ischemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2009; 16: 1323-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fregni F, Boggio PS, et al.: A sham-controlled trial of a 5-day course of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the unaffected hemisphere in stroke patients. Stroke. 2006; 37: 2115-2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kakuda W, Abo M, et al.: A multi-center study on low-frequency rTMS combined with intensive occupational therapy for upper limb hemiparesis in post-stroke patients. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2012; 9: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsuura A, Onoda K, et al.: Magnetic stimulation and movement-related cortical activity for acute stroke with hemiparesis. Eur J Neurol. 2015; 22: 1526-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hesse S, Werner C, et al.: Combined transcranial direct current stimulation and robot-assisted arm training in subacute stroke patients: a pilot study. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2007; 25: 9-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nowak DA, Grefkes C, et al.: Interhemispheric competition after stroke: brain stimulation to enhance recovery of function of the affected hand. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2009; 23: 641-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huynh W, Vucic S, et al.: Exploring the evolution of cortical excitability following acute stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2016; 30: 244-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rossini PM, Burke D, et al.: Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord, roots and peripheral nerves: Basic principles and procedures for routine clinical and research application. An updated report from an I.F.C.N. Committee. Clin Neurophysiol. 2015; 126: 1071-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]