Abstract

With growing interest in cancer therapeutics, anti-angiogenic therapy has received considerable attention and is widely administered in several types of human cancers. Nonetheless, this type of therapy may induce multiple signaling pathways compared with cytotoxics and lead to worse outcomes in terms of resistance, invasion, metastasis, and overall survival (OS). Moreover, there are important challenges that limit the translation of promising biomarkers into clinical practice to monitor the efficiency of anti-angiogenic therapy. These pitfalls emphasize the urgent need for discovering alternative angiogenic inhibitors that target multiple angiogenic factors or developing a new drug delivery system for the current inhibitors. The great advantages of nanoparticles are their ability to offer effective routes that target the biological system and regulate different vital processes based on their unique features. Limited studies so far have addressed the effectiveness of nanoparticles in the normalization of the delicate balance between stimulating (pro-angiogenic) and inhibiting (anti-angiogenic) factors. In this review, we shed light on tumor vessels and their microenvironment and consider the current directions of anti-angiogenic and nanotherapeutic treatments. To the best of our knowledge, we consider an important effort in the understanding of anti-angiogenic agents (often a small volume of metals, nonmetallic molecules, or polymers) that can control the growth of new vessels.

Keywords: Cancer, tumor vessels, tumor microenvironment, anti-angiogenic agents, nanotherapeutics, drug resistance, biomarkers, metastasis.

Introduction

There are many different types of therapies for cancer treatment. However, the choice of cancer therapy is determined by various factors such as the types of tumors (benign or malignant), the stage of diagnosis, and the potential ability of the patient to tolerate the prescribed treatments 1. At present, surgical resections are coupled with chemotherapy or radiotherapy to avoid the occurrence and growth of invisible occult microscopic tumors, even after complete surgical resection 2. However, these conventional strategies (i.e., chemotherapy and radiation) for cancer treatment have poor specificity, dose sensitivity and bioavailability. Furthermore, they do not greatly differentiate between cancerous and normal cells 3. As a result of continual treatment, the cancerous cells susceptible to certain drugs become resistant against them, which leads to further complications such as multidrug resistance (MDR), a situation where conventional therapies fail due to the resistance of tumor cells to one or more drugs 4.

One of the frontiers in the fight against cancer is the regulation of angiogenesis, i.e., the emergence of new blood vessels. Targeting angiogenesis can be an effective approach to prevent the development of new blood vessels and is an essential modality for normalizing the tumor-associated vasculature. Thus, it can prevent the development of tumors and can serve as a complementary therapeutic paradigm for cancer therapy 5, 6. However, different disease progression patterns can be induced by anti-angiogenic therapies, which may lead to worse outcomes in terms of drug resistance, invasion, and metastasis 7. In addition, the poor oral availability and short half-life of such therapies necessitate their regular parenteral administration 8. Currently, it is often attractive for medical applications to design therapeutic monitoring, targeted delivery and controlled drug release into a single platform 9. Owing to the unique properties of nanoparticles (NPs), nanotherapeutics have the potential to provide a more effective and safe mode to circumvent the discrepancies associated with conventional cancer therapies 10, 11. Moreover, “intelligent” vehicles possessing specific physicochemical properties (e.g., size, shape, and surface chemistry) and biological entities (protein, small interfering RNA (siRNA)) can be designed by manipulating nanocarrier characteristics to support therapeutic agents to avoid the clearance mechanisms of the living systems 12. Therefore, the association of anticancer drugs with NPs may provide a sensible method for the delivery and prevention of drug resistance 13, 14.

In this review, we first attempt to focus on the nature of tumor vessels and how they can be normalized under current conditions with anti-angiogenic agents in light of their benefits. Next, we describe the pitfalls associated with tumor abnormality and anti-angiogenic agents. Moreover, the potential advantages of NPs as an alternative therapeutic are also discussed. Finally, we illustrate the effectiveness of nanotherapeutics considering their design aspects.

Abnormality of tumor vessels and their microenvironment

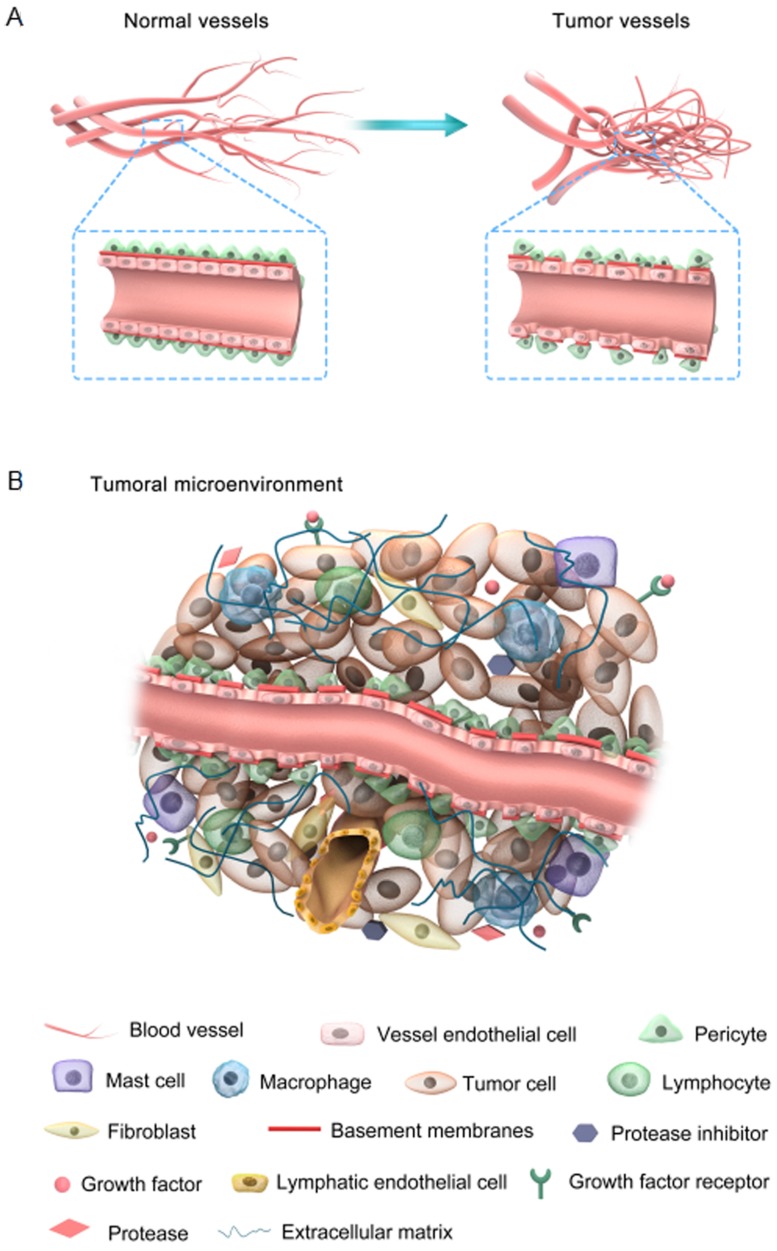

Tumor vessels display abnormal structure and function with an apparent chaotic organization due to the imbalanced expression of angiogenic factors and inhibitors 15. The features of both tumor and normal vessels are comparatively illustrated in Figure 1A. It is well understood that normal blood vessels show a hierarchical distribution of different blood vessels including arteries, veins, and capillaries. For example, endothelial cells (ECs) are aligned tightly as monolayers in the inner wall of vessels, acting as an endothelial barrier. The basement membranes of ECs are intact and uniform, intermediated by pericytes that are tightly associated with ECs. In contrast, tumor blood vessels are unorganized. Tumor ECs neither develop regular monolayers nor possess a normal endothelial barrier-like function, which leads to chaotic blood flow and vessel leakiness. Basement membranes of tumor ECs are discontinuous or absent with maximum gap diameters as large as several hundred nanometers 16. These membranes are abnormally and loosely associated with ECs and have various thicknesses. Tumor ECs are covered by fewer pericytes, which are mounted upon each other and loosely connected to the ECs.

Figure 1.

(A) Comparison between normal and tumor vessels; (B) Characteristic features of the tumor microenvironment.

The tumor microenvironment is mainly comprised of four components: the blood vasculature, the extracellular matrix (ECM), the supporting stromal cells, and a suite of signaling molecules (Figure 1B). Different cell surface receptors and extracellular matrix proteins are expressed on the surface of tumor-associated blood vessels. In addition, these vessels produce several chemokines, adhesion molecules, and growth factors that provoke lymph-angiogenesis 17, 18. In tumor tissues, there are no distinct functional lymphatic vessels due to their excessive condensation, particularly at the center of the tumor. However, functional lymphatic vessels exist in the tumor margin and peritumoral tissue. These peritumor lymphatics are hyperplastic, collecting fluid and mediating tumor metastasis through the lymphatic network 19. The excessive depletion and leakage of fluid from the tumor center and vessels, respectively, results in interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) and impaired blood supply, which ultimately lead to hypoxia induction, which mediates angiogenesis and drug resistance 20. However, the lymphatic network in normal tissue maintains a balance of interstitial fluid by draining the excessive fluid out of the tissues 21. Furthermore, the metabolic behavior of tumor cells is adapted to meet their proliferative demands with notable modifications such as enhanced rates of glycolysis in both aerobic and anaerobic conditions 22. Accordingly, the pH in tumors is lower than in normal tissues. This pH gradient is valuable for controlling cancer therapy, since different drugs and carriers are internalized through endocytosis and trapped within endosomal and lysosomal compartments 23. Briefly, abnormal tumor vessels together with physiological barriers may lead to a hostile tumor microenvironment, which is revealed by marked gradients in the rate of cell proliferation, high IFP and regions of hypoxia and acidosis 15. Note that the abovementioned abnormal conditions create a physiological barrier to the delivery of therapeutic agents to the tumor site and do not impair tumor cell proliferation and survival 5. Accordingly, normalization of the tumor vasculature and its microenvironment enhances the penetration of therapeutic agents into the tumor cells in a potentially lethal concentration.

Vascular normalization

In normal tissues, the balance of anti- and angiogenic factors is well maintained. Excess production of angiogenic stimulators (e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)) or reduced production of angiogenic inhibitors (e.g., thrombospondin-1) may result in the development of different types of malignancies, infectious disorders, and inflammations 24. Maintenance of angiogenic factors may lead to reducing the IFP and enhancing tumor oxygenation, and thus will eventually improve drug diffusion into targeted tissues 25. In general, a normalized vasculature possesses less leaky, less tortuous, and less dilated blood vessels that contain a well-structured and regular basement membrane. Investigating the molecular basis of such alternative patterns of vessel growth can be of great value towards the improved efficacy of anti-angiogenic therapy 26. Considerable success has been achieved in the last two decades. For example, targeting VEGF signaling has induced vessel normalization in tumors, pruning of unnecessary immature vessels, reduced vessel diameter, improved perfusion, and decreased vessel tortuosity 19, 27. A recent study showed that the blockage of the placental growth factor (PlGF), another important member of the VEGF family, normalized the tumor vessels in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) models to some extent through a reduction in vessel tortuosity and formation of hypoperfused string vessels 28. The findings confirmed that this type of PIGF blockage sequentially improved the efficacy of VEGF-targeted therapy 29, 30.

Other targeted factors, such as platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) (e.g., blockage of PDGFB) 31, angiopoietin (Ang) families 32, regulator of G-protein signaling 5 (Rgs5) 33, nitric oxide 34, integrins family 35 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) 36, may be inhibited and potentially contribute in the regulation of vessel normalization. In addition, several other agents causing vascular normalization, including several proteolytic enzymes, show their effects through indirect anti-angiogenic activity. For example, trastuzumab can mimic an anti-angiogenic cocktail and thus significantly decreases the volume, diameter, and permeability of tumor vessels and generates more regular networks 37. In a separate study, the haplodeficiency of oxygen-sensing prolyl hydroxylase domain protein PHD2 effectively normalized the endothelial lining, which further minimized vessel leakiness and favored improved tumor perfusion and oxygenation 38. Therefore, targeting angiogenic signaling pathways with judicious anti-angiogenic agents may increase the efficacy of vessel normalization, making them more efficient for the delivery of oxygen and drugs.

Current anti-angiogenic agents

The current anti-angiogenic agents, either recently approved for anti-cancer therapy or entering clinical investigations (Table 1), are manufactured with the aim of preventing tumor cells from obtaining nutrients by eradicating the available vessels in some tumor types and hindering the formation of new vessels6, 39. Because of the integral role of the vasculature in this process, one noticeable theoretical advantage of anti-angiogenic therapy would be that some of these steps may be compromised, particularly in primary tumors (e.g., via the destruction of the immature vasculature to prevent and/or suppress intravasation), as well as in distant sites (e.g., the prevention of the “angiogenic switch” in a vascular metastasis).

Table 1.

Existing anti-angiogenic drugs for cancer therapy.

| Anti-angiogenic drug | Main Targets | Clinical status | Indications | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bevacizumab [Avastin] | Anti-VEGFA antibody | Approved | Advanced metastatic cancers [Lung, colorectal, renal, breast, and recurrent glioblastoma]. | 19, 40 |

| Sunitinib [Sutent, SU11248] | Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Approved | Renal and advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. | 41 |

| Pazopanib [Votrient, Armala™, Gw786034] | Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Approved | Metastatic renal cell cancer. | 42 |

| Sorafenib [Nexavar, BAY 43-9006] | Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Approved | Metastatic renal and unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. | 43, 44 |

| Axitinib [AG-013736] | Multikinase inhibitor | Approved | Cancer of lung, gastrointestinal, thyroid, breast, renal and pancreas. | 45 |

| Cediranib [recentin™, AZD2171] | Multitargeted anti-angiogenic agents | Approved | Recurrent glioblastoma, non-small cell lung cancer and colorectal cancer. |

46 |

| Vatalanib [PTK787, ZK222584] |

Small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Approved | Metastatic neuro-endocrine tumors, tumors of brain and central nervous system, and colorectal cancer. | 47 |

| Brivanib [BMs-582664] | VEGFR1-3, FGFR1-3 | Approved | Multiple tumor types including colorectal and hepatocellular carcinoma. | 48 |

| Nintedanib [ BiBF 1120, Vargatef™] | Multitargeted anti-angiogenic agents | Approved | Non-small cell lung cancer. | 49 |

| Vandetanib [Zactima] | Multitargeted pan-VEGF-RTKIs | Approved | Medullary thyroid cancer. | 50 |

| Ziv-aflibercept (Zaltrap) | VEGF-A, VEGF-B and PIGF | Approved | Metastatic colorectal cancer. | 51 |

| Regorafenib (Stivarga) | Multikinase inhibitor | Approved | Metastatic colorectal cancer. | 51 |

| Temsirolimus (Torisel) | Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) | Approved | Advanced renal cell carcinoma. | 52 |

| Everolimus (Afinitor) | Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) | Approved | Pancreatic neuroendocrine and other solid tumors. | 53 |

| Ranibizumab [Lucentis] | Anti-VEGF | Preclinical | Treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. | 54 |

| Pegaptanib [Macugen] | Anti-VEGF | Preclinical | Patients with wet age-related macular degeneration. | 55 |

| DC101 | Anti-VEGFR2 | Preclinical | Induces pressure gradient across the vasculature and improves drug penetration in solid tumors. | 56 |

Furthermore, the anti-angiogenic vessel pruning strategy can effectively improve the potency of chemotherapy in several ways, for example, through the partial normalization of the tumor-associated vasculature by differentiation between the tumor-associated vasculature and tumor cells and their selective targeting, improved bioavailability, and enhanced drug delivery to the tumor site 19, 57. The activity of VEGF is commonly inhibited by bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody 58. Compared to a placebo, bevacizumab more effectively delayed progression time in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients 59. Owing to its improved efficacy, as confirmed by the randomized phase II trials, a combination therapy consisting of bevacizumab and irinotecan is highly recommended and has been approved for the treatment of recurrent glioblastoma 40. A separate study has shown that combining VEGF inhibitors and chemotherapy effectively prolonged the survival of patients suffering from metastatic colorectal cancer, advanced-level lung cancer, and metastatic breast cancer 60. However, clinical trials have revealed that bevacizumab monotherapy is less effective than combination therapy and is associated with bleeding, venous or arterial thromboembolic events and hypertension 61. Moreover, bevacizumab does not function directly to block angiogenesis but rather cures the disease condition through the normalization of tumor vasculature 19. VEGF signaling can also be blocked through the inhibition of VEGFR and PDGF by using a small molecule, for example, tyrosine kinases inhibitors (TKIs). To date, four different inhibitors for different applications have been approved by the FDA: sunitinib [Sutent, Pfizer] and pazopanib [Votrient] for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (RCC), sorafenib [Nexavar, Bayer] for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and metastatic RCC, and vandetanib [Zactima] for medullary thyroid cancer 26. Several other agents are also in clinical trials. For example, Avastin is used off-label for curing wet age-related macular degeneration, a disease condition that is characterized by the neovascularization of leaky vessels, and it is composed of an anti-VEGF aptamer (pegaptanib [Macugen] and a VEGF Fab (ranibizumab [Lucentis])) 54, 55.

Despite major advances in the clinical development of anti-angiogenic inhibitors, the appropriate dosing pattern and duration of the VEGF receptor for the treatment of cancer is yet to be established in further clinical trials. Previous studies have shown that anti-angiogenic inhibitors such as TKIs are often unable to obtain access to tumor-associated vessels; therefore, such inhibitors often exhibit a poor biodistribution and pharmacokinetic profile in addition to having critical side effects 62, 63. Furthermore, these inhibitors developed multidrug resistance and enhanced invasiveness during treatments that have limited effects on the OS, and authenticated prognostic biomarkers are unavailable for monitoring the response to a treatment 39, 64.

Targeting tumor abnormalities and antiangiogenic limitations by nanotherapeutics

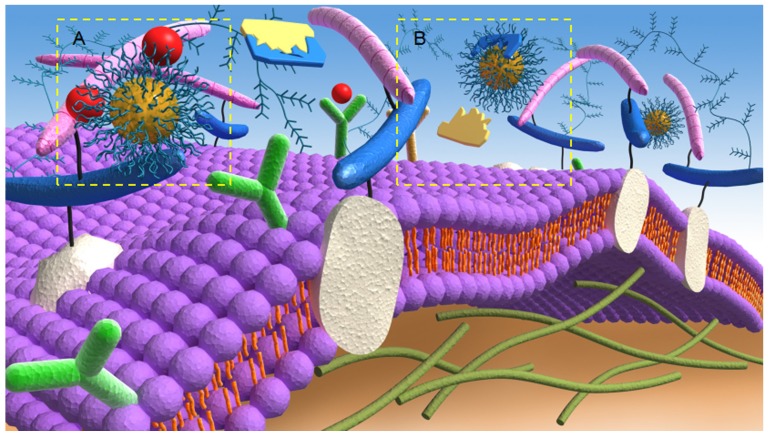

The main mechanism involved in the nanotherapeutic approach to anti-angiogenesis activity is the prevention of binding of pro-angiogenic factors to their respective receptors (Figure 2A). Since the ECs of tumors and normal tissues have different features, targeting the vasculature with therapeutic NPs can be optimized by the conjugation of antibodies/ligands, such as the anti-VEGFR-2 antibody, that are capable of binding these overexpressed antigens/receptors. These receptors stimulate gene expression and intracellular signaling that are involved in vital and critical cellular processes, such as cell growth, apoptosis, survival, metastasis, invasion, and tumor cell motility 65. Therefore, the binding of these antigens/receptors to functionalized NPs offer opportunities for tumor targeting and attack 66. For instance, after the specific binding between angiogenic growth factors and their relevant receptors, ECs are activated and release several proteases that can effectively degrade the basement membrane and ECM 5. Based on this fact, researchers have developed anticancer strategies that target the related proteolytic enzymes participating in the angiogenesis cascades. Such targeting can be considered to be another important mechanism of anti-angiogenesis via a nanotherapeutic approach to inhibit the activity of ECM proteolytic enzymes (Figure 2B). For example, Li et al. 67 designed a combination nanosystem of low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) and ursolic acid (UA) to inhibit matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) enzymes 68. In their system, they synthesized an amphiphilic LMWH-UA (LHU) conjugate and self-assembled nanodrugs, which possessed both anti-angiogenic activity and a very low level of anticoagulant activity, into the core (UA)/ shell (LMWH). The new nanosystem demonstrated superior stability and better pharmacokinetic and distribution characteristics and showed limited side effects. Moreover, the solubility can be increased through binding with hydrophilic LMWH, which may further assist intravenous administration.

Figure 2.

Anti-angiogenic mechanisms of targeting A) angiogenic growth factors and B) proteolytic enzymes of the extracellular matrix by nanotherapeutics.

Targeting antigen-antibody interactions may also improve tumor vessel permeability, which plays a critical role in drug diffusion. For example, anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) immunoliposomes facilitated intracellular drug delivery to the breast tumor sites and displayed higher therapeutic efficacy compared to non-targeted liposomes 69. Additionally, the abnormal vessel porosity can be avoided by using functionalized NPs. Studies have reported that NPs coated with a polyethylene glycol (PEG) layer are able to bypass the abnormal vessel porosity by minimizing non-specific cellular uptake and prolonging the circulation time 70. Finally, the combination of taxane therapy with NPs (or a hedgehog inhibitor (IPI-926)) has been used to overcome the reduced vascular density and perfusion rates of the tumors 71. Another combination system, such as a polyelectrolyte complex (PEC) micelle-based siRNA, efficiently enhanced drug delivery to tumor sites 72.

A hostile tumor microenvironment also has the ability to fuel tumor progression and drug resistance. Nanotherapeutics have been designed to deliver the drug in response to the tumor microenvironment (e.g., hypoxia, elevated IFP and acidic pH). For example, the hypoxia-sensitive polymeric micelles encapsulating doxorubicin (DOX) effectively targeted the hypoxic microenvironment 73, whereas the intermediate-sized nanoparticles (20-40 nm) blocked the VEGFR-2 signal and decreased the elevated IFP 74. Interestingly, pH-sensitive polyHis-PEG (poly (L-histidine)-polyethylene glycol) and gelatin NPs have been designed and demonstrated variable drug release kinetics at different pH values 75, 76.

On the other hand, nanotherapeutics demonstrate attractive solutions for the limitation of anti-angiogenic therapy by opening new prospects for drugs that cannot be used efficiently as conventional formulations due to poor oral availability, short half-life and continuous parenteral administration. For example, nanopolymeric Lodamin (TNP-470 conjugated to mono-methoxy-polyethylene glycol-polylactic acid) showed advantageous drug delivery characteristics, such as controllable drug release, prolonged systemic circulation lifetimes and targeting abilities 8. The association of anticancer drugs with NPs represents a logical way to combat cancer drug resistance. Several types of nanotherapeutics, including mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) 77, cyclosporin A (CyA) and doxorubicin in polyalkylcyanoacrylate NPs 78, and a combination of tamoxifen and paciltaxel NPs 79, have been developed in different ways to overcome multidrug resistance. These NPs, in addition to their ability to overcome MDR, have demonstrated desirable advances, such as increased intracellular uptake, decreased complex side effects and regular delivery of NPs to the target cells. Further details describing cancer anti-angiogenic barriers and limitations and how they can be addressed by using the advantages of nanoparticles are summarized in Table 2 and discussed in the following subsections.

Table 2.

Promising solutions by nanoparticles to overcome barriers for cancer therapy.

| Barrier for cancer therapy | Promising solutions | Example of used NPs | Outcome | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular vessel permeability | Activate the target by covalent conjugation of antibodies to NP surfaces. | Immunoliposomes (Anti-HER2) | Increased drug uptake and facilitated intracellular drug delivery. | 69 |

| Abnormal vessel porosity | Prolong drug systemic circulation. | Liposomes, polyethylene glycol (PEG) NPs. | Improved drug availability and leading to superior tumor uptake. | 70 |

| Reduce vascular density and perfusion rates | Reducing the interstitial fluid pressure in solid tumors. | Combination of Taxane therapy with NPs or using a Hedgehog inhibitor (IPI-926) | Improve the functional vascular density and enhance drug delivery to tumors. | 71 |

| Targeting and systemic treatment of cancer | Delivered into the target tissue. | Apolyelectrolyte complex (PEC) micelle-based siRNA delivery system. | Efficiently delivered and readily taken up by cancer cells. | 72 |

| Hypoxic microenviornments | Induce drug delivery. | Hypoxia-sensitive polymeric micelles encapsulating DOX | Effectively deliver the drugs into hypoxic cells. | 73 |

| Elevated interstitial fluid pressure | Increasing interstitial transport of drug. | Intermediate-sized nanoparticles (20-40 nm) targeting VEGFR-2 | Decreases the interstitial fluid pressure and enhanced drug delivery. | 74 |

| Acidic microenviornments | pH-sensitive NPs | -Poly His containing nanogel and hydrogel NPs. -Gelatin nanoparticles | Sped up drug release kinetics and increase drug efficacy. | 75, 76 |

| Multidrug-resistant (MDR) and drug-efflux pumps | Stimuli-responsive drug release. | Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) | Increase intracellular uptake and enhanced ability to overcome MDR. | 77 |

| Drug efflux and MDR phenotype | Bypass the efflux pumps through endocytosis. | Cycloporin A (CyA) and doxorubicin in polyalkylcyanoacrylate NPs. | Prevent complex side effects and regularly deliver NPs to the target cells. | 78 |

| Reduce the apoptotic threshold in MDR | Increase the apoptotic activity | Combination therapy of tamoxifen and paciltaxel nanoparticles. | Significant enhancement in antitumor efficacy without any toxicity. | 79 |

| Poor oral availability, short half-life and continuous parenteral administration | Increase intestinal absorption and drug selectivity | Nanopolymeric Lodamin (TNP-470 conjugated to mono-methoxy-polyethylene glycol-polylactic acid) | Selectively inhibited tumor growth and metastasis without any side effect. | 8 |

Inherent resistance against anti-angiogenic therapy

Cancer resistance remains the major obstacle in angiogenesis treatments of many cancer types and requires to be addressed cautiously. The development of tumor resistance towards anti-angiogenic agents can be either inherent or acquired. In contrast to acquired resistance, the phenomena of inheritance of resistance against the anti-angiogenic agent are multifaceted events with a greater influence on the tumor microenvironment 27, 80.

In addition, only few examples of inherent resistance against the anti-angiogenic therapies, mostly the tumors acquire resistance towards the therapies through the upregulation of signals that are responsible for tumor growth, progression, and metastasis 63. The mutated and developed mechanisms of resistant anti-angiogenic therapies may be related to the genetic instability of tumor cells that occurs in situations when only a single protumorigenic pathway is targeted. Another possibility of inherent resistance against the drug could be vascular co-option, in which the tumor-associated cells proliferate in the vicinity of existing blood vessels and receive nutrients from them, and hence avoid further angiogenesis 81. Various mechanisms, their predictive biomarkers and the consequent clinical evidence are described in Table 3 and can provide an explanation for acquired resistance. However, these mechanisms show that in over two decades of positive preclinical studies, only modest incremental changes have been demonstrated in the clinic 80, 82. Hence, it is imperative to understand why most patients stop responding, or do not respond at all, to angiogenic drugs and how such limitations can be overcome.

Table 3.

Mechanisms by which tumors acquire resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies.

| Mechanism of Resistance | Example of predictive marker | Clinical evidence | Referefnce(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulation of compensatory pro-angiogenic signals | Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) | Induction of FGF2 in patient's serum that progressed on anti-VEGF therapy. | 83 |

| Increase in pro-angiogenic factors by stromal cells | Tumor associated fibroblasts (TAFs) | Tumors resistant to anti-VEGF therapy produce TAFs which support tumor growth and angiogenesis. | 84 |

| Recruitment of bone marrow derived pro-angiogenic cells | Circulating endothelial cells (CECs) | Increased after AZD2171 and sunitinib treatments of renal cell cancer patients. | 83, 85 |

| Over expression of vascular pericytes coverage | Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) | Targeting tumor vasculature pericytes may lead to disturbance of vessel integrity and metastasis. | 86 |

| Induction of hypoxia | Hypoxia-induced factor-1 (HIF-1) | Increased the circulating levels of basic FGF and stromal cell-derived factor 1 alpha (SDF1α) that controlled by HIF-1 after VEGF blockade. | 87 |

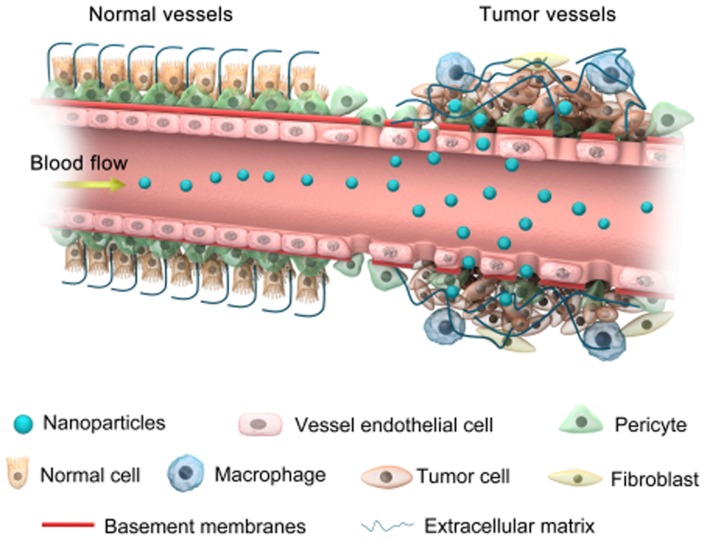

Progress in nanomedicines based on NPs is anticipated to overcome drug resistance 88. For example, the size of NPs, which can easily be controlled in different ways, allows them to intrinsically approach the metastasized tumors via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effects (Figure 3) without being recognized by the main target in drug resistance, P-glycoprotein 89. The optimum size of NPs also increases the ability to escape the immune system through non-fouling modification, which further achieves potent positive targeting of the site of the disease via molecular specific recognitions, efficient combating of cancer drug resistance, and enhanced drug bioavailability 90. Recently, studies have shown that poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO)-poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) NPs successfully co-delivered paciltaxel and ceramide drugs to the target site to overcome MDR in breast cancer cell lines 79.

Figure 3.

Accumulation of nanoparticles in tumor tissues via the EPR effect.

There has been a major challenge in VEGF targeting therapies due to the upregulated expression of several other pro-angiogenic factors, for example, FGF-2, which can function to develop tumor resistance against the anti-VEGF therapy 91, 92. Efforts have been made to find efficient therapies that can concurrently block the activities of both VEGF and FGF pathways to ensure the complete halting of tumor growth. Li et al. 93 applied a VF-Trap fusion protein to block the activities of both VEGF and FGF-2 and monitored the anti-angiogenic effects both in vitro and in animal models. Their results indicated that the VF-Trap fusion protein demonstrated an active inhibition of VEGF and FGF-2-induced EC proliferation and migration. The simultaneous blockade of VEGF and FGF-2 more efficiently inhibits retinal angiogenesis and tumor growth compared to the blockade of only VEGF.

Enhanced invasiveness, metastasis and the effects on overall survival

Recent research in preclinical settings has demonstrated that anti-angiogenic agents may enhance or facilitate metastatic disease growth and tumor invasiveness 7. In separate studies in mouse models, the treatment of glioblastoma and pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma with VEGF inhibitors promoted invasiveness in the primary tumors 94 and induced metastasis in the liver and lymph nodes 95. Since anti-angiogenic therapy contributes to hypoxia and might initiate an array of stromal and microenvironmental defense mechanisms 82, it may lead to a more aggressive and invasive tumor phenotype 63. In addition, both tumor- and host-mediated responses to anti-angiogenic therapy, at least in certain instances, can accelerate an invasive and a metastatic potential after treatment in distant organs 95, 96. Several reports indicated that anti-angiogenic agents mainly targeted the primary tumor and halted their growth, whereas their long-term effects were rarely observed and only caused a moderate improvement in progression-free survival (PFS) and slightly benefited OS 82, 97. Moreover, there is no compelling clinical evidence that the treatments will translate benefits to a long-term OS gain 98. An alternate possibility is that in the clinic, VEGF-targeted therapies can induce a more aggressive tumor phenotype leading to a lack in the OS advantage 99. A more convincing argument for this obvious incongruity is that tumors can establish resistance against anti-VEGF therapy 39, 100. Therefore, the outcome of using anti-angiogenic agents is nearly facilitating the tumor growth in existing and adjacent sites and does not frequently correspond to robust gains in the OS in most of the patients who in due course relapsed and progressed rapidly 63.

At present, there is not an apparent effective therapy for invasive and distributed metastatic cancer owing to the low accumulation of drug concentration at the target sites. For a case in point, different nanotherapeutics have been designed using metal oxides to recognize gliomas including receptor- and cell-mediated drug delivery systems 101. Poly (lactic acid) (PLA) NPs coated with functional polysaccharide have been used in vivo as an attractive drug carrier and enhanced NP accumulation at the tumor sites 102. Further studies established that the OS limitations were overcome by facilitating superior dose scheduling that improved the patient quality of life 103, 104. For instance, cisplatin-loaded, multilayered PLA nanofibers prevent local cancer recurrence and increase the OS with lower toxicity 105. More recently, the developed functionalized NPs such as IT-101, a conjugate of camptothecin and a cyclodextrin-based polymer, have significantly prolonged circulation lifetimes, successfully entered the tumor matrix, and allowed slow and controlled drug release 106. Preliminary results of a Phase-I clinical trial demonstrated that compatible doses of IT-101 exhibited a long-term stable disease curative effect (approximately 1 year and more)107. Similarly, the oral formulation of TNP-470 (Lodamin) administered for cancer therapy and prevention of liver metastasis has shown considerable results. The study revealed that Lodamin effectively inhibited primary tumor growth in melanoma and lung cancer models. Further, it effectively prevented liver metastasis without any risk of side effects, e.g., liver-toxicity, and extended mouse survival 8.

Response biomarkers for anti-angiogenic therapy

Due to the discrepancies associated with anti-angiogenic agents and their modest responses, it can be of great value to investigate and establish a set of biomarkers that can screen the populations of possible responders. Further, these biomarkers must have the potential to monitor disease progression and angiogenic activity of malignancies in response to treatment with great efficacy and accuracy. For instance, the results shown by combining the anti-angiogenic agent with chemotherapy are acceptable for treating all types of tumors. The setup failed to provide any progress in terms of survival when treating previously treated metastatic breast cancer 60. One possible explanation for this failure could be the formation of other pro-angiogenic factors by the resistant tumors 108. Therefore, it would be a more optimistic approach to identify biomarkers capable of predicting the efficacy of bevacizumab and other associated VEGF-targeted therapies. Several potential anti-angiogenic biomarkers have been studied, including dynamic measurements (e.g., changes in systemic blood pressure), genotypic markers (e.g., VEGF polymorphism), circulating markers (e.g., plasma levels of VEGF), blood cells (e.g., progenitor cells), tissue markers (e.g., IFP) and imaging parameters (e.g., Ktrans, a measure of capillary permeability in the vessels by using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)) 109. Although recent studies have provided promising data regarding consistent biomarkers for monitoring the efficiency of VEGF inhibitors, imperative challenges and key queries to be explained still exist, thus limiting their translation into clinical practice (Table 4).

Table 4.

Biomarkers for monitoring the efficiency of VEGF inhibitors and limitations.

| Biomarkers | Examples | Anti-angiogenic agent | Cancer type | Limitations | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating | Plasma VEGF | Bevacizumab, Vandetanib, or Sunitinib | Metastatic breast, non-small cell lung cancer, and hepatic cell carcinoma. | Is not specific for one drug and can't be notable as prognostic or predictive. | 110-112 |

| Blood cells | Progenitor Cells |

Bevacizumab, Sunitinib or Cediranib. | Hepatic cell carcinoma. | Only decreased in patients treated with sunitinib and did not affected in case of others. | 110 |

| Imaging | MRI (Ktrans) | Vatalanib, Sunitinib, Axitinib, or Cediranib | Multiple tumors. | Drop at different times after treatment and the optimal time of evaluation is not clear. | 110, 113 |

| Dynamic | Hyper-tension | Bevacizumab or Axitinib | Multiple tumors. | Not validated in large studies. | 114, 115 |

| Genotype | VEGF-634CC and VEGF-1498 TT genotypes | Bevacizumab | Metastatic breast cancer. | Dose-limiting markers. | 114 |

| Tissue | Interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) | Vatalanib or Imatinib | Mammary and colon carcinoma. | Not significantly reflect the features of tumors and depend on the host vasculature. | 116 |

Biomarkers that are specifically expressed or overexpressed in cancer cells can be a target for nanotherapeutics. For instance, lipocalin 2 (Lcn2, or NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin)) is a potential diagnostic biomarker for a variety of epithelial cancers. For example, in breast cancer, it promotes progression through the induction of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition and enhances angiogenesis through increasing the level of VEGF 117, 118. Therefore, Lcn2 can be considered a promising therapeutic target of the anti-angiogenesis strategy in cancer treatment. Guo et al. developed a novel Lcn2 siRNA delivery system utilizing a liposome as a carrier via intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) 119. The molecular ICAM-1-targeted Lcn2 siRNA-encapsulated liposome (ICAM-Lcn2-LP) connected human triple-negative breast cancer TNBC MDA-MB-231 cells that are extensively stronger than non-neoplastic MCF-10A cells. An effective silencing of Lcn2 by ICAM-Lcn2-LPs resulted in a substantial reduction in the production of VEGF from MDA-MB-231 cells, which caused a marked reduction in angiogenesis both in vitro and in vivo. In addition, other biomarkers such as somatostatin receptors (SSTRs) are overexpressed in glioma and can also be utilized as targets for anti-angiogenic nanotherapeutics 120.

The potential of biomarkers to identify and characterize a disease condition provides a clue for the development of several tags on one nanovector coupled with anti-angiogenic agents, as long as they do not interact with each other to reduce their systemic side effects 121. Currently, it is well established that applications of imaging modalities are promising approaches to noninvasively track the response to anti-angiogenic therapy 122. For example, perfluorocarbon NPs combined with various agents, such as fluorine isotope 19 (19F) or gadolinium (Gd), have been effectively attached to the αvβ3 integrin antibody. The structural formation was confirmed by visualization through MRI in mouse and rabbit models 123. Integrin targeting was optimized through the design of novel peptide moieties, possessing higher affinity for integrins than the current Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) tags in practice 124. Furthermore, an RGD-functionalized nanocarrier was used as a contrast agent that allows the detection of ongoing angiogenesis and the distinction between the angiogenesis intensities of different tumor models by directly targeting the αvβ3 receptor. With this technology, a combination of complementary and noninvasive imaging modalities, i.e., MRI and NIRF (near-infrared fluorescence) is provided to reliably monitor the response to anti-angiogenic therapy. Additionally, this technology could be used as a noninvasive contrast agent for angiogenic phenotyping 125. The abovementioned efforts conducted by various research groups have opened gateways for the noninvasive detection of different types of cancers in clinical trials, in addition to other diseases that are identified by abnormal vasculature, e.g., atherosclerosis and various cardiovascular diseases 126.

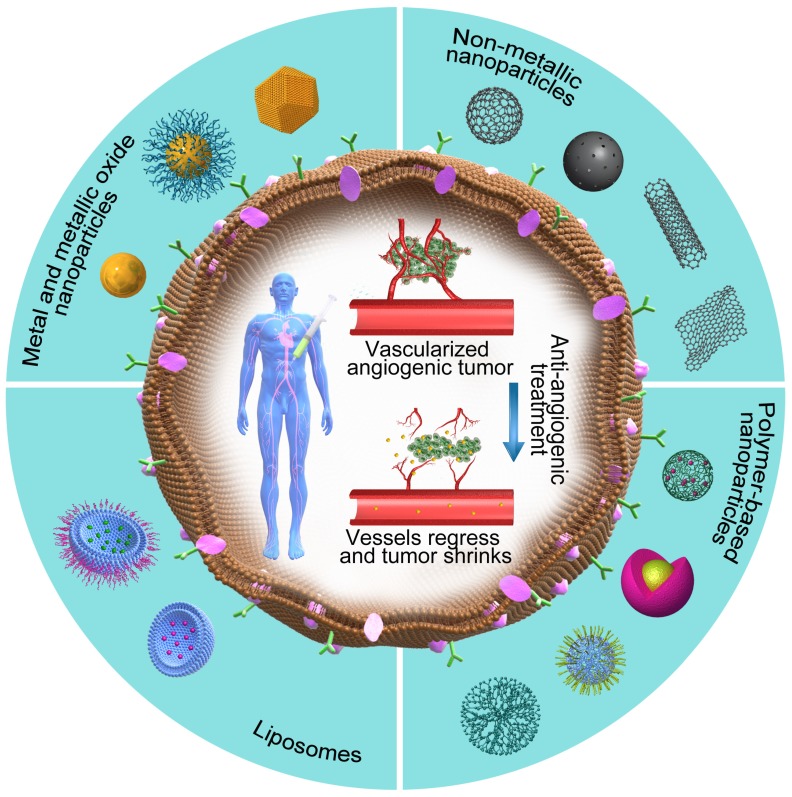

Nanotherapeutics as effective angiogenic inhibitors

Among several pro-angiogenic factors secreted by a variety of tumors, VEGF is a highly overexpressed and well-characterized tumor-derived pro-angiogenic factor 127. During its action, the anti-angiogenic nanotherapeutics attach to VEGF and prevent its binding with the respective receptor, thus avoiding the initiation of new blood vessels. Based on this concept, a variety of NPs with anti-angiogenic properties (Figure 4, Table 5) have been developed by researchers around the world in the past decade.

Figure 4.

The potential promises of nanotherapeutics. The outer part of the figure shows different categories of NPs that are used as anti-angiogenic therapeutics, whereas the core part shows the vessel regression and tumor shrinkage caused by anti-angiogenic nanotherapeutics.

Table 5.

Anti-angiogenic nanoparticles and their therapeutic effects.

| Categories | Examples | Advantages | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal NPs | Au NPs | Inhibits the activity of cell surface kinase, VEGFR2 and AKT phosphorylation. | 90, 134 |

| Ag NPs | Inhibited VEGF- and IL-1-induced vascular permeability in porcine retinal endothelial cells and induced cell survival in BRECs. | 135, 136 | |

| Copper | Inhibited HUVEC proliferation, migration, tube formation, and cell cycle. | 137, 138 | |

| Metallic oxide NPs | Cuprous oxide | Inhibited HUVEC proliferation, migration, tube formation, and cell cycle. | 129 |

| Cerium oxide | Inhibited VEGF165-induced cell proliferation and phosphorylation of VEGFR2. | 139, 140 | |

| Non-metallic NPs | Carbon | Potentially accumulated in tumor microenvironment and inhibits angiogenesis. | 141 |

| Silica | Showed anti-angiogenic effects on the retinal neovascularization and in orthotropic ovarian tumor-bearing nude female BALB/c mice. | 142 | |

| Polymeric nanoconjugates | HPMA copolymers | Reduced tumor growth rate in human melanoma and lung carcinoma. | 143 |

| PLGA | Reduced tumor metastasis through suppression of tumor necrosis factor. | 144 | |

| PEG-PLA | Improved the anti-angiogenic ability of PTX and inhibited the proliferation, migration and tube formation of HUVECs. | 145 | |

| Chitosan | Inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis in an aggressive breast cancer. | 146 | |

| Aptamer-based nanotherapeutics | Result in potent and selective inhibition of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. | 147 | |

| poly(b-amino esters) NPs | Leading to significant vascular regeneration in ischemic tissues. | 148 | |

| Lipid-based nanoparticles | Nanopolymeric micelles | Accumulate selectively in tumors, inhibiting tumor progression, angiogenesis and multiplication. | 8 |

| Nano-liposomes | Targeted to somatostatin receptors (SSTRs), improved the anti-angiogenic ability of PTX. | 120 |

From the materials aspect, these anti-angiogenic NPs can be mainly divided into three categories, i.e., metal/metallic oxide NPs 128, 129, non-metallic NPs 130, 131 and polymer-based NPs 132, 133. The following paragraphs will address the anti-angiogenic strategies of cancer nanotherapeutics considering these categories.

Metal and metallic oxide NPs

Nanoparticles have been extensively studied with vast applications in the biomedical field, including targeted drug delivery, optical bioimaging, biosensors, and immunoassay. For example, gold, (Au), silver (Ag), copper (Cu), and cerium oxide (CeO2) NPs are favorable prospects in anti-angiogenic treatments with their main action targeting VEGF. Studies have demonstrated that AuNPs show anti-angiogenic properties 149, 150. For example, Mukherjee et al. found that spherical bare AuNPs (5 nm) showed anti-angiogenic activity by effectively inhibiting the VEGF165-induced proliferation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). They further considered the anti-angiogenic activity of AuNPs to explore their mechanism of action by binding to VEGF165 via the heparin binding domain and repressing the role of the cell surface kinase receptor, which leads to the anti-angiogenesis cascade 90. Their further investigation revealed that AuNPs have the potential to bind bFGF and inhibit its activity, which also prompted anti-angiogenesis. Additionally, Mukherjee and coworkers found that the AuNP activity was greatly dependent on NP size. NPs with 20-nm diameters offered more binding space to VEGF165 and exhibited a larger inhibition efficacy compared to small-sized NPs (5 nm). Moreover, they demonstrated that 20 nm AuNPs with negative charges (-40 mV) exhibited superior anti-angiogenesis activity, which was ascribed to the electrostatic binding between the negatively charged AuNPs and the positively charged heparin binding domain of VEGF165 90. It is well established that the competitive binding of exogenous materials to the pro-angiogenic factors will inhibit the normal binding of these factors to their specific receptors and thus interrupt the subsequent angiogenesis cascade. A study examining the effect of AuNPs on the interaction of VEGF with its receptors using advanced visualization approaches such as quantum dot (NSOM/QD) imaging and near-field scanning optical microscope showed that the NPs inhibited VEGF165-induced VEGFR2 and serine/threonine kinase (AKT) phosphorylation 134. Recent studies have shown that AuNPs can be considered as therapeutic mediators for targeting tumor microenvironments and can disturb the crosstalk between stellate and cancer cells by inhibiting the growth in desmoplastic tissues and tumors 151, 152.

Silver NPs (AgNPs) are another important anti-angiogenic species in cancer nanotherapeutics. Both chemically and biologically synthesized AgNPs showed anti-angiogenic properties 135, 136. The mechanism of the anti-angiogenesis of AgNPs mainly exists in the inhibition of VEGF activity by AgNPs, which halts the VEGF-provoked proliferation and migration of ECs. Kalishwaralal et al. investigated the anti-angiogenesis effects of AgNPs that were synthesized from Bacillus licheniformis in bovine retinal endothelial cells (BRECs) via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT dependent pathway 153. The synthesized AgNPs successfully inhibited VEGF-provoked cell migration, proliferation, and cell-survival in the cell line under investigation. Copper (Cu), cupric oxide (CuO) and cuprous oxide (Cu2O) NPs are also regarded as potential anti-angiogenic materials 137, 138. In vitro and in vivo studies of the anti-angiogenic activity of CuO- and Cu-NPs demonstrated that the NPs inhibited HUVEC cell migration, proliferation, cell cycle (arrest in S-phase), and tube formation in a dose-dependent pattern 129. In addition, cerium oxide (CeO2) NPs were also investigated and showed anti-angiogenic properties through the inhibition of VEGF165-induced HUVEC capillary tube formation and proliferation 139, 140.

Non-metallic NPs

These types of NPs play a vital role in nanotherapeutics for cancer treatment. For example, silica and silicate-based NPs can either be utilized as anti-angiogenic agents or employed as vehicles for anti-angiogenic drugs or genes in cancer therapy 154. Jo et al. investigated the anti-angiogenic effects of silica NPs on retinal neovascularization through a series of in vitro and in vivo assays and found that the anti-angiogenic effects of these NPs were associated with the inhibition of VEGFR-2 phosphorylation 155. Chen et al. developed a delivery system of VEGF-small interfering RNA (siRNA) based on silica NPs 142. This delivery system was composed of a magnetic mesoporous silica core, a cap of polyethylenimine (PEI) for siRNA absorbance, a PEG corona for long circulation, and a fusogenic peptide (KALA). The authors demonstrated that the system showed highly efficient siRNA delivery and remarkable inhibition effects on angiogenesis without significant side effects on the major organs of orthotropic ovarian tumor-bearing nude female BALB/c mice.

In vitro and in vivo studies have indicated that various carbon-based NPs had anti-angiogenic properties in cancer therapies. These anti-angiogenic carbon-based nanomaterials include diamond and graphite NPs, graphene sheets, and multiwalled carbon nanotubes 156, 157. Similar to NPs of metal/metallic oxide and silica-based materials, the anti-angiogenesis mechanism of carbon-based NPs is associated with the inhibition of VEGF-induced proliferation and migration of ECs. Research has indicated that these carbon NPs could down-regulate the VEGF receptor, which ultimately results in a drop-off in hypoxia-mediated angiogenesis 141.

Polymer-based NPs

Nanoparticles of polymers from both synthetic and natural derivations have received utmost consideration in various aspects of the biomedical field, especially drug delivery systems for cancer therapies and other diseases. PEG and polylactic acid (PLA) are commercially available biodegradable polymers, which have been approved by the FDA for use as carriers for the controlled and targeted release of anticancer drugs. Fibronectin extra domain B (EDB) is specifically expressed on both glioma neovasculature ECs and glioma cells (GCs). This unique feature of EDB was addressed by Chen et al. They synthesized the EDB-targeted peptide APTEDB-modified PEG-PLA NPs (APT-NPs) and loaded paclitaxel (PTX) for the tumor neovasculature and tumor cells for dual-targeted chemotherapy 142. The in vitro tube formation assay and in vivo Matrigel angiogenesis analysis demonstrated that the anti-angiogenic ability of PTX was significantly improved by the APT-NPs. In a similar study, the joint group of Qiu and Di 145 fabricated PEG-PLA-based NPs modified by APRPG (Ala-Pro-Arg-Pro-Gly) peptide encapsulating inhibitors of angiogenesis (TNP-470) (TNP-470-NP-APRPG). In vitro assays suggested that TNP-470-NP-APRPG could effectively inhibit the proliferation, migration, and tube formation of HUVECs. Similarly, the in vivo studies demonstrated tumor growth retardation in SKOV3 ovarian cancer-bearing mice. These observations suggested a noteworthy decrease in the angiogenesis and anti-therapeutic efficiency of TNP-470-NP-APRPG.

Natural polymers such as chitosan and bacterial cellulose are extensively employed for broad-spectrum medical applications owing to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, high water holding potential, low immunogenicity, and negligible toxicity 158-160. Xu's group fabricated and evaluated the potential of chitosan NPs to inhibit the establishment of human hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts using the anti-angiogenic mechanism 161. Detailed mechanistic analysis using the biochemistry and molecular biology approaches such as immuno-histochemistry and qRT-PCR demonstrated that the anti-tumor activity of chitosan NPs were provided by an anti-angiogenic effect coupled with low concentrations of VEGF and VEGFR-2. The suppression of VEGFR-2 resulted in the blockage of VEGF and demonstrated anti-angiogenic activity towards EC proliferation. In addition to the anti-angiogenic properties of the materials, chitosan NPs are also employed as vehicles for delivering of anti-angiogenic agents, e.g., drugs and genes, to their target sites during cancer therapies. Pillé et al. fabricated chitosan-coated polyisohexylcyanoacrylate (PIHC) NPs to carry the anti-RhoA siRNA to the tumor site. In vivo studies demonstrated that the NPs significantly inhibited both angiogenesis and tumor growth in an aggressive breast cancer mouse xenograft model 146. It has been well established that VEGF165 is naturally present in two different isoforms, which work in an antagonistic fashion: the first isoform, VEGF165a, is angiogenic in nature, whereas the second one, VEGF165b, is anti-angiogenic 162. Researchers are inspired to develop potential therapeutics capable of selectively inhibiting VEGF165a and not VEGF165b, which would be a great advantage in improving the anti-angiogenic activity and therapeutic benefit. Kohane et al. 163 reported the selective binding of C-6 hydroxyl (C-6 OH) sulfated hyaluronic acid (HA) to the VEGF165 angiogenic isoform. They found that reduced sulfation of C-6 OH in the N-acetyl-glucosamine repeat unit of HA produced a polymer with a great affinity for VEGF165a compared to VEGF165b. This C-6 OH sulfated HA has potential application as a drug delivery particle in VEGF-targeted therapy.

Consequently, the effectiveness of NPs has contributed to the development of angiogenesis therapeutic research including cancer and has driven scientists to think 'outside of the box'. Much effort has been made to use nanotechnology to progress functional modalities to manage and improve vascular normalization in a preclinical setting. Although the preclinical outcomes are promising, they are not realizable with other modalities. Further confirmation research is required from the medical community to assess this progressive technology and develop it into a clinical verity.

Design considerations for nanotherapeutics

A sufficient concentration of a therapeutic drug must reach the target cancer cells for maximum efficacy, but at the same time, the drug should be highly selective in its action without exerting adverse effects on normal tissues. A logical method for efficient cancer drug delivery and targeting can be obtained by the association of anti-cancer drugs with functionalized NPs 145, 164. However, many factors can affect NP distribution, including size, chemical modification, surface properties, and shape 89, 165. Among these, the size of NPs remains a vital factor in the normalization of tumor vessels and the approach to the tumor sites 74. For highly and poorly permeable tumors, the optimal diameter size for enhanced accumulation in the tumor site can vary. The diameter range should be <100 nm for tumors with dense stroma 166. As such, NPs in the range of 10-200 nm are more appropriate for cancer treatment. Generally, NPs ≤10 nm can easily be filtered out through the kidneys, whereas NPs ≥200 nm are primarily accumulated within the extracellular spaces, and thus, both these sizes are unable to reach the target sites 167. In addition to the size of NPs, their shape is another key factor that significantly accounts for their efficacy. For example, studies have demonstrated that macromolecules possessing linear and semi-flexible structural configurations are distributed more effectively within the interstitial matrix compared to rigid-spherical particles of the same size 168. Moreover, the shape of NPs has a significant impact on the circulation time. For example, Yan et al. reported that the circulation time of filamentous micelles is approximately 10-fold greater compared to their spherical counterparts. Similarly, filamentous nanotubes with a small diameter of less than 2 nm demonstrated rapid renal clearance and showed a circulation time of less than 3 h 169. In addition, the chemical modification of NPs surface also provides the possibility for the attachment of tumor-targeting molecules 170. The effective goal of these modifications is the design of multifunctional NPs that can deliver therapeutic agents to a tumor, reducing nonspecific interactions and controlling the surface charge, which assists in avoiding the NP distribution to off-target moieties and sites. Nonetheless, no such accurate system is available at present that can completely prevent the non-specific interactions, and thus, particle loss is always observed to some extent 167. However, the main target of current research is to minimize these interactions to the maximum possible extent.

On the other hand, NPs can be designed to improve the efficiency of therapeutics and respond to features in the tumor microenvironment, such as partial oxygen pressure and acidity 10, 171. The characteristic lower pH of solid tumors compared to normal tissues provides a basis for the establishment of several pH-sensitive nanocarriers for delivering drugs to tumor sites 172, 173. In addition to pH responsiveness of tumors as an approach, NPs can also be directed towards the tumors through the application of other external stimuli, e.g., magnetic field and electric pulses 174, 175, ultrasound, heat, and light 176. A more recent advancement in NP formulation has been shown to deliver siRNAs to tumor sites in humans 72. Therefore, different types of NPs have been synthesized and evaluated for their potential to deliver a variety of anti-angiogenic materials (e.g., drugs).

Briefly, the main consideration in the development of anti-tumor drugs is to target specific proteins/cellular receptors that are expressed excessively in tumors and/or angiogenic blood vessels. Thus, the design of nanotherapeutics for such applications should be carried out carefully and must possess the following features: (1) competent differentiation between normal and cancerous cells and between the forms of proteins and cellular receptors that are involved in the respective signaling pathways, (2) the ability to quantitatively determine the expression level of multiple tumor types, and (3) the ability to block the activity of tumor angiogenic vessels and thus be utilized as a therapeutic intervention.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The deformed structure and functionalities of tumor-associated vasculature provide sufficient information to combat the challenges associated with anti-cancer therapies. Although such therapies demonstrate an effective treatment of cancer in certain settings, considerable benefits remain unrealized for most patients in terms of invasiveness, metastasis and overall survival. In addition, these therapies are often accompanied by side effects and toxicity to healthy cells. With a growing number of anti-angiogenic agents being approved or considered for approval, the need for biomarkers is more critical than ever for drug efficiency and safety. Strategies to curb drug resistance are also required. The progress of nanotechnology offers the best opportunities for researchers to develop new nanotherapeutics and continue to search for other alternative agents that, when clinically approved, will strongly impact and facilitate treatment decisions. In short, the future of cancer treatment by nanotherapeutics requires more knowledge regarding cancer cell metabolic behaviors, physiological barriers, and other allied subjects such as material properties to improve the efficiency of nanotherapeutics.

Vocabulary

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is related to a situation where conventional therapies fail due to the resistance of tumor cells to one or more drugs. The interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) describes a reduction in fluid mobility through the interstitium and usually occurs due to excessive compression in new blood vessels by tumor cells. The tumor microenvironment mainly comprises four components: the blood vasculature, the extracellular matrix (ECM), the supporting stromal cells, and a suite of signaling molecules. The biomarkers in this paper refer to markers that can predict the efficacy and accuracy of anti-angiogenic agents. Nanoparticles (NPs) are particles with a small size (mainly less than 100 nm) that is anticipated to overcome the limitations of anti-angiogenic agents.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (General Program, No. 21574050) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2015 M580640, 2016 M602291) for their financial support.

Abbreviations

- Ang

angiopoietin

- BRECs

bovine retinal endothelial cells

- CECs

circulating endothelial cells

- CyA

cyclosporin A

- DOX

doxorubicin

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- ECs

endothelial cells

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- FGF-2

fibroblast growth factor-2

- GCs

glioma cells

- GISTs

gastrointestinal stromal tumors

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HER-2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- ICAM-1

intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IFP

interstitial fluid pressure

- Lcn2

lipocalin 2

- LMWH

low-molecular-weight heparin

- MDR

multidrug resistance

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MSNs

mesoporous silica nanoparticles

- NGAL

neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin

- NIRF

near-infrared fluorescence

- NPs

nanoparticles

- OS

overall survival

- PDGFs

platelet-derived growth factors

- PEC

polyelectrolyte complex

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PEO

poly(ethylene oxide)

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PHD2

prolyl hydroxylase domain containing protein 2

- PIHC

polyisohexylcyanoacrylate

- PLA

polylactic acid

- PlGF

placental growth factor

- PolyHis-PEG

poly (L-histidine)-polyethylene glycol

- RCC

renal cell carcinoma

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SSTRs

somatostatin receptors

- TAFs

tumor associated fibroblasts

- TKIs

tyrosine kinases inhibitors

- UA

ursolic acid

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR-2

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2.

References

- 1.Wolinsky JB, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Local drug delivery strategies for cancer treatment: gels, nanoparticles, polymeric films, rods, and wafers. J Control Release. 2012;159:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellon JR, Come SE, Gelman RS. et al. Sequencing of chemotherapy and radiation therapy in early-stage breast cancer: updated results of a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1934–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghadjar P, Vock J, Vetterli D. et al. Acute and late toxicity in prostate cancer patients treated by dose escalated intensity modulated radiation therapy and organ tracking. Radiat Oncol. 2008;3:35. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-3-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holohan C, Van Schaeybroeck S, Longley DB. et al. Cancer drug resistance: an evolving paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:714–26. doi: 10.1038/nrc3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:417–27. doi: 10.1038/nrd3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heath VL, Bicknell R. Anticancer strategies involving the vasculature. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:395–404. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebos JM, Lee CR, Kerbel RS. Tumor and host-mediated pathways of resistance and disease progression in response to antiangiogenic therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5020–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benny O, Fainaru O, Adini A. et al. An orally delivered small-molecule formulation with antiangiogenic and anticancer activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:799–807. doi: 10.1038/nbt1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia F, Liu X, Li L. et al. Multifunctional nanoparticles for targeted delivery of immune activating and cancer therapeutic agents. J Control Release. 2013;172:1020–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang S, Shao K, Liu Y. et al. Tumor-targeting and microenvironment-responsive smart nanoparticles for combination therapy of antiangiogenesis and apoptosis. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2860–71. doi: 10.1021/nn400548g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vivek AK, Nichole LT, Shi S. et al. Highly angiogenic peptide nanofibers. ACS Nano. 2015;9:860–8. doi: 10.1021/nn506544b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang XQ, Lam R, Xu X. et al. Multimodal nanodiamond drug delivery carriers for selective targeting, imaging, and enhanced chemotherapeutic efficacy. Adv Mater. 2011;23:4770–5. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brannon-Peppas L, Blanchette JO. Nanoparticle and targeted systems for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang XJ, Chen C, Zhao Y. et al. Circumventing tumor resistance to chemotherapy by nanotechnology. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;596:467–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-416-6_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tredan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K. et al. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1441–54. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashizume H, Baluk P, Morikawa S. et al. Openings between defective endothelial cells explain tumor vessel leakiness. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1363–80. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farkkila A, Anttonen M, Pociuviene J. et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor VEGFR-2 are highly expressed in ovarian granulosa cell tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:115–22. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Logan P, Burnier J, Burnier MN. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression and inhibition in uveal melanoma cell lines. Ecancermedicalscience. 2013;7:336. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2013.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Annamaria R, Melillo G. Role of the hypoxic tumor microenvironment in the resistance to anti-angiogenic therapies. Drug Resist Updat. 2009;12:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jain RK, Stylianopoulos T. Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:653–64. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khazaei T, McGuigan A, Mahadevan R. Ensemble modeling of cancer metabolism. Front Physiol. 2012;3:135. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bae YM, Park YI, Nam SH. et al. Endocytosis, intracellular transport, and exocytosis of lanthanide-doped upconverting nanoparticles in single living cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33:9080–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain RK, Tong RT, Munn LL. Effect of vascular normalization by antiangiogenic therapy on interstitial hypertension, peritumor edema, and lymphatic metastasis: insights from a mathematical model. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2729–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Bock K, Cauwenberghs S, Carmeliet P. Vessel abnormalization: another hallmark of cancer? Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell. 2011;146:873–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukumura D, Jain RK. Tumor microvasculature and microenvironment: targets for anti-angiogenesis and normalization. Microvasc Res. 2007;74:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van de Veire S, Stalmans I, Heindryckx F. et al. Further pharmacological and genetic evidence for the efficacy of PlGF inhibition in cancer and eye disease. Cell. 2010;141:178–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer C, Jonckx B, Mazzone M. et al. Anti-PlGF inhibits growth of VEGF(R)-inhibitor-resistant tumors without affecting healthy vessels. Cell. 2007;131:463–75. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rolny C, Mazzone M, Tugues S. et al. HRG inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by inducing macrophage polarization and vessel normalization through downregulation of PlGF. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hellberg C, Östman A, Heldin CH. PDGF and vessel maturation. Cancer Res. 2010;180:103–14. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-78281-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Augustin HG, Young Koh G, Thurston G. et al. Control of vascular morphogenesis and homeostasis through the angiopoietin-Tie system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:165–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamzah J, Jugold M, Kiessling F. et al. Vascular normalization in Rgs5-deficient tumours promotes immune destruction. Nature. 2008;453:410–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashiwagi S, Tsukada K, Xu L. et al. Perivascular nitric oxide gradients normalize tumor vasculature. Nat Med. 2008;14:255–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cordes N, Cerniglia GJ, Pore N. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition modulates the microenvironment by vascular normalization to improve chemotherapy and radiotherapy efficacy. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Izumi Y, Xu L, di Tomaso E. et al. Tumour biology: herceptin acts as an anti-angiogenic cocktail. Nature. 2002;416:279–80. doi: 10.1038/416279b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazzone M, Dettori D, Leite de Oliveira R. et al. Heterozygous deficiency of PHD2 restores tumor oxygenation and inhibits metastasis via endothelial normalization. Cell. 2009;136:839–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ. Pathways mediating resistance to vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6371–5. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vredenburgh JJ, Desjardins A, Herndon JE. et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan in recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4722–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert JM, Thomas EH, Piotr T. et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Jozef M. et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1061–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM. et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:125–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V. et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;259:378–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michael AT, Ezra EWC, Yazdi KP. et al. Pharmacokinetics of single-agent axitinib across multiple solid tumor types. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;74:1279–89. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2606-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramalingam SS, Mack PC, Vokes EE. et al. Cediranib (AZD2171) for the treatment of recurrent small cell lung cancer (SCLC): A California Consortium phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:431–6. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sobrero AF, Paolo B. Vatalanib in advanced colorectal cancer: two studies with identical results. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1938–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hung H, Van Chanh N, Joseph F. et al. Brivanib alaninate, a dual inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and fibroblast growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases, induces growth inhibition in mouse models of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6146–53. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reck M, Kaiser R, Mellemgaard A. et al. Nintedanib (bibf 1120) plus docetaxel in nsclc patients progressing after first-line chemotherapy: lume lung 1, a randomized, double-blind phase iii trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2631–2. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brassard M, Rondeau G. Role of vandetanib in the management of medullary thyroid cancer. Biologics. 2012;6:59–66. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S24220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Lakomy R. et al. Addition of aflibercept to fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan improves survival in a phase III randomized trial in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer previously treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3499–506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P. et al. Temsirolimus, inter-feron alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2271–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T. et al. Everolimus for advanced pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. 2011. 2011;364:514–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Abouammoh M, Sharma S. Ranibizumab versus bevacizumab for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:152–8. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32834595d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hariprasad SM, Shah GK, Blinder KJ. Short-term intraocular pressure trends following intravitreal pegaptanib (Macugen) injection. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141:200–1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tong RT, Boucher Y, Kozin SV. et al. Vascular normalization by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 blockade induces a pressure gradient across the vasculature and improves drug penetration in tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3731–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bagri A, Berry L, Gunter B. et al. Effects of anti-VEGF treatment duration on tumor growth, tumor regrowth, and treatment efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3887–900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chauhan VP, Stylianopoulos T, Martin JD. et al. Normalization of tumour blood vessels improves the delivery of nanomedicines in a size-dependent manner. Nat Nanotechnol. 2012;7:383–8. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2012.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM. et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:427–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller KD, Chap LI, Holmes FA. et al. Randomized phase III trial of capecitabine compared with bevacizumab plus capecitabine in patients with previously treated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:792–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamba T, McDonald DM. Mechanisms of adverse effects of anti-VEGF therapy for cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:1788–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Quesada AR, Medina MA, Alba E. Playing only one instrument may be not enough: limitations and future of the antiangiogenic treatment of cancer. Bioessays. 2007;29:1159–68. doi: 10.1002/bies.20655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ebos JM, Kerbel RS. Antiangiogenic therapy: impact on invasion, disease progression, and metastasis. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:210–21. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shojaei F. Anti-angiogenesis therapy in cancer: current challenges and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2012;320:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith NR, Baker D, James NH. et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptors VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 are localized primarily to the vasculature in human primary solid cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3548–61. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Parveen S, Misra R, Sahoo SK. Nanoparticles: a boon to drug delivery, therapeutics, diagnostics and imaging. Nanomedicine. 2012;8:147–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li Y, Wu Y, Huang L. et al. Sigma receptor-mediated targeted delivery of anti-angiogenic multifunctional nanodrugs for combination tumor therapy. J Control Release. 2016;228:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang JS, Ren TN, Xi T. Ursolic acid induces apoptosis by suppressing the expression of FoxM1 in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Med Oncol. 2012;29:10–5. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park JW, Kirpotin DB, Hong K. et al. Tumor targeting using anti-her2 immunoliposomes. J Control Release. 2001;74:95–113. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00315-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Barenholz Y. Pharmacokinetics of pegylated liposomal Doxorubicin: review of animal and human studies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2003;42:419–36. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Griffon-Etienne G, Boucher Y, Brekken C. et al. Taxane-induced apoptosis decompresses blood vessels and lowers interstitial fluid pressure in solid tumors: clinical implications. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3776–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim SH, Jeong JH, Lee SH. et al. Local and systemic delivery of VEGF siRNA using polyelectrolyte complex micelles for effective treatment of cancer. J Control Release. 2008;129:107–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thambi T, Son S, Lee DS. et al. Poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(lysine) copolymer bearing nitroaromatics for hypoxia-sensitive drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2016;29:261–70. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang W, Huang Y, An Y. et al. Remodeling tumor vasculature to enhance delivery of intermediate-sized nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2015;9:8689–96. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b02028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Griset AP, Walpole J, Liu R. et al. Expansile nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and in vivo efficacy of an acid-responsive polymeric drug delivery system. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2469–71. doi: 10.1021/ja807416t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]