Abstract

Age-related hearing loss is experienced by one-third of individuals 65 years and older and can be socially debilitating. Historically, there has been poor correlation between age-related threshold changes, loss of speech understanding, and loss of cochlear hair cells (HCs). We examined changes in ribbon synapse number at four ages in Fisher Brown Norway (FBN) rats, an extensively studied rat model of aging. In contrast to previous work in mice/Wistar rats, we found minimal ribbon synapse loss before 20 months (m), with significant differences in 24m and 28m rats at 4 kHz. Significant outer HC loss was observed at 24m and 28m in low to mid-frequency regions. Age-related reductions in ABR wave I amplitude and increases in threshold were strongly correlated with ribbon synapse loss. Wave V/I ratios increased across age for click, 2, 4, and 24 kHz. Together, we find that ribbon synapses in the FBN rat cochlea show resistance to aging until ~60% of their lifespan, suggesting species/strain differences may underpin decreased peripheral input into the aging central processor.

1. Introduction

Presbycusis, or age-related hearing loss, is arguably the third most common malady of industrialized populations. It is a complex, multifaceted condition involving primary changes to the auditory periphery and maladaptive, compensatory changes in the central auditory pathway. Epidemiological studies have shown that the prevalence of hearing loss in the United States (US) doubles every decade of life, affecting 30% of the US population aged 65 to 74 years, and 50% of the population over 75 years of age (Lin, Thorpe et al. 2011). US census data suggest that the population of those over 65 will grow from 14% in 2014 to near 21% by 2040 (https://aoa.acl.gov/), dramatically increasing the number of patients suffering from age-related hearing loss. Loss of speech understanding resulting from presbycusis is socially debilitating and can lead to isolation and depression (Dalton, Cruickshanks et al. 2003).

The peripheral auditory system, housed in the cochlea of the inner ear, contains outer hair cells (OHCs) and inner hair cells (IHCs) which convert sound waves into electrical signals. IHCs are connected to type I spiral ganglion neurons (SGNs) by ribbon synapses (also known as IHC-SGN synapses), which are a unique glutamatergic synapse found in hair cells (HCs), retinal photoreceptors, and pinealocytes (for review Matthews and Fuchs 2010). In the mammalian cochlea, each type I SGN synapses with one IHC (Spoendlin 1969, Kiang, Rho et al. 1982, Liberman 1982), but each IHC is connected to 10–30 SGNs by a ribbon synapse (Liberman 1980, Bohne, Kenworthy et al. 1982, Stamataki, Francis et al. 2006). Within each synapse, the ribbon complex is made of proteins such as ribeye, basson, and C-terminal binding protein 2 (Ctbp2), and allows a large number of vesicles to dock at the presynaptic terminal to facilitate rapid release of glutamate in response to Ca2+ influx (reviewed in Moser, Brandt et al. 2006). On the postsynaptic side, bipolar SGNs, whose dendrites are unbranched, express AMPA receptors (Safieddine and Eybalin 1992, Matsubara, Laake et al. 1996, Glowatzki and Fuchs 2002). Loss of IHC-SGN synapses, caused by aging, toxic drugs, or acoustic trauma, reduces spontaneous and driven excitatory input to the central auditory nervous system (CANS) resulting in complex, compensatory plastic changes that are frequently characterized by a down-regulation of glycinergic and GABAergic inhibition (Caspary, Ling et al. 2008, Roberts, Eggermont et al. 2010, Auerbach, Rodrigues et al. 2014, Gold and Bajo 2014). In a normal, young adult cochlea, the majority (>95%) of Ctbp2-labeled presynaptic regions overlap with the postsynaptic density on axon terminals of SGNs that express AMPA receptors containing the GluR2 subunit (Matsubara, Laake et al. 1996, Furman, Kujawa et al. 2013, Sergeyenko, Lall et al. 2013).

The auditory brainstem response (ABR) is an evoked far-field potential elicited by acoustic stimuli, whose sequential waves reflect acoustic transmission from the acoustic nerve to pre-collicular or collicular auditory structures (Buchwald and Huang 1975, Starr and Hamilton 1976). Tonotopic organization is a shared feature among most CANS structures, reflecting the cochlea’s frequency-specific place map, with responses to higher frequencies at the base and lower frequencies at the apex (Greenwood 1990, Muller 1991). ABR responses to pure-tone and click stimuli have historically been used in human and animals to assess acoustic thresholds, with responses to click stimuli thought to most closely approximate behavioral thresholds in human subjects (Jerger and Mauldin 1978, Gorga, Worthington et al. 1985, van der Drift, Brocaar et al. 1987, Williamson, Zhu et al. 2015, Frisina, Ding et al. 2016).

Historically, auditory research has found poor correlations between age-related loss of speech understanding, age-related changes in pure-tone auditory thresholds, and age-related loss of cochlear HCs (Starr, Picton et al. 1996). Hearing threshold sensitivity, as measured by pure tones, is also not directly affected by degeneration of SGNs when scattered across the cochlea (Schuknecht and Woellner 1953, Schuknecht and Woellner 1955). However, recent studies suggest that loss of ribbon synapses connecting IHCs and SGNs may be a more salient marker for functional auditory losses (Kujawa and Liberman 2009). Thus, age-related loss of IHC-SGN synapses, which decreases excitatory auditory input to the brain, may be a critical factor signaling CANS compensatory changes, where in an attempt to “re-up” the gain, inhibitory neurotransmission is selectively down-regulated (Caspary, Ling et al. 2008, Roberts, Eggermont et al. 2010, Auerbach, Rodrigues et al. 2014, Gold and Bajo 2014). Studies in CBA/CaJ and UM-HET4 mice, as well as Wistar rats, have shown that age-related loss of IHC-SGN synapses could be detected many weeks before there were changes in auditory thresholds measured by ABR (Sergeyenko, Lall et al. 2013, Altschuler, Dolan et al. 2015, Mohrle, Ni et al. 2016).

The present study correlated age-related IHC-SGN synapse changes with evoked auditory potential changes from the CANS of Fisher Brown Norway (FBN) rats. In 1994, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) recommended the FBN strain as a superior model for aging research. FBN rats are a F1 hybrid of Fischer 344 (F344) and Brown-Norway rats, and have a longer median lifespan relative to mice and other rat strains. Specifically, FBN rats have a 50% longer median life span than F344 rats [34 months (m) vs. 25m, respectively] with fewer pathologic lesions late in life (Lipman, Chrisp et al. 1996, Lipman 1997). The FBN rat model has been extensively used to demonstrate age-related changes in inhibitory neurotransmission and temporal processing of acoustic information in central auditory structure (Milbrandt and Caspary 1995, Caspary, Holder et al. 1999, Caspary, Schatteman et al. 2005, Ling, Hughes et al. 2005, Turner and Caspary 2005, Turner, Hughes et al. 2005, Caspary, Hughes et al. 2006, Caspary, Ling et al. 2008, Schatteman, Hughes et al. 2008, Wang, Turner et al. 2009, de Villers-Sidani, Alzghoul et al. 2010, Hughes, Turner et al. 2010, Richardson, Ling et al. 2011, Wang, Brozoski et al. 2011, Richardson, Ling et al. 2013, Gold and Bajo 2014). Previous studies have shown that the FBN strain has severe presbycusis at low frequency regions with ~75% OHC loss observed in the apical turn and less than ~25% OHC loss in the high frequency basal turn at 32m (Keithley, Ryan et al. 1992, Caspary, Ling et al. 2008). This differs from humans and other rodent strains which have presbycusis in high frequency regions (Willott 1991, Frisina and Frisina 1997, Frisina and Walton 2006).

The present study recorded ABR potentials from rats at four ages (4–6m, 20m, 24m, and 28m) followed by analysis of HCs and IHC-SGN synapses in the same ears using methods similar to Sergeyenko et al (2013).

2. Methods

2.1 Animals

Male FBN rats aged 4–6m (n=9), 20m (n=9), 24m (n=8), and 28m (n=7) were obtained from the NIA aged rodent colony (Bethesda, MD) and housed by Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) before arriving at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine (SIUSOM). Ambient sound levels were measured by Charles River personnel with no information regarding frequency spectra provided. Sound pressure levels (SPLs) varied in rooms housing FBN rats at Charles River depending on the closeness of the racks to the washer and vacuum systems. With both systems off, ambient SPLs varied between 56–60 dB. A cage washer was on 5–6 hrs/day, while a vacuum system ran a total of 1–2 hrs/day in “spurts” of 20 min. SPLs with the washer alone, were between 72–75 dB. With both systems on, SPLs at the nearest rack could reach as high as 81 dB. It is assumed that most of the energy was at low frequencies, not likely to damage rodent hearing. This was the case for SIUSOM animal facilities, which showed ambient, unweighted SPLs between 2.0–49 kHz at 39 dB. No energy above 30 dB was observed in the 1.0–2.0 kHz bin. A distant cage washer had little effect on background levels down to 1.0 kHz, but levels below 1.0 kHz could reach 79 dB with cage-washer and air handler rumble. The SIUSOM animal rooms housing FBN rats were assessed using a Bruel & Kjaer (B&K, Norcross, GA) pulse sound measurement system (Pulse 13.1 software) with a 3560C module and a B&K 4138 microphone. All animal studies were performed in accordance with approved animal protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at SIUSOM.

2.2 Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) Measurements

Prior to ABR recordings, rats were anesthetized with an intramuscular injection of a 3:1 mixture of ketamine and xylazine at a dose of 105 mg/kg ketamine and 7 mg/kg xylazine (dose for 20m and 24m rats were reduced by 10% and 28m rats by 20%). Anesthesia depth was checked by heart rate and toe pinch. After reaching a stable anesthesia state (~220 pulses/min for 4–6m rat, ~200 pulses/min for 20m and 24m, and ~180 pulse/min for 28m rat), the rat’s head was shaved. One recording electrode was inserted into the skin at the vertex, with a second reference electrode inserted just under the mastoid of the left ear. A ground wire was attached to the hind leg. An electrostatic speaker [EC1, Tucker Davis Technologies (TDT) System III, (Alachua, FL)] was fitted to a tube placed and fixed in the left ear canal. ABRs were recorded in a double-wall soundproof booth (Industrial Acoustic, Bronx, NY).

Acoustic signals were generated using a 16-bit D/A converter [RX6, TDT System III (Alachua, FL)], controlled by customized Auditory Neurophysiology Experiment Control Software (ANECS, Blue Hills Scientific, Boston, MA). Clicks and pure tones for generating ABRs were delivered in 5 dB steps between 0 and 80 dB. Stimuli were clicks and 2, 4, 12, and 24 kHz pure tone bursts presented 512 times at a rate of 20/s, 3 ms duration with a 1 ms rise/fall time. Electroencephalographic far-field potentials were amplified 200,000 times and filtered between 300 Hz and 10 kHz with data collected and analyzed offline. ABR thresholds, latencies, and amplitudes were obtained based on the average waveforms. The peak of wave I was used to measure the threshold and latency. The amplitude change between the peak and trough of wave I at 80 dB was considered the wave I amplitude. The same criteria was applied to wave V. The ratio of wave V to wave I was calculated at the same intensity for each animal at tested pure-tone frequencies and click. Aged rats with thresholds higher than 80 dB at certain frequencies were excluded from amplitude analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (San Diego, CA).

2.3 Immunostaining

Temporal bones were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA) for 2–3 hours at room temperature, followed by decalcification in 120 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 3–4 weeks as previously described (Montgomery and Cox 2016). Samples were stored in 10 mM Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) at 4°C until use. Cochlea were dissected into apical, middle, and basal turns using a whole-mount method and routine immunostaining procedures were performed on free-floating cochlear turns as previously described (Montgomery and Cox, 2016) with the one exception that the primary antibody incubation was performed at 37°C in a hybridization oven. The following primary antibodies were used: mouse IgG1 anti-Ctbp2 (1:500, cat#BDB612044, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), mouse IgG2a anti-GluR2 (1:200, cat#MAB397, Millipore, Billerica, MA), and rabbit anti-myosin VIIa (1:200, cat#25-6790, Proteus BioSciences, Inc., Ramona, CA). The following secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen (Waltham, MA) and used at a 1:1000 dilution: Alexa-488 goat anti-mouse IgG2a (cat#A21131), Alexa-568 goat anti-rabbit (cat#A11036), and Alexa-647 goat anti-mouse IgG1 (cat #A21240). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (1:2000, cat#H1399, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Images were taken using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope and image analysis was performed using Leica LAS AF LITE software.

2.4 Ribbon synapse and HC quantification

IHC-SGN ribbon synapses and HCs from the same ear were quantified in immunostained cochlear whole mounts in a subgroup of ABR tested animals [4–6m (n=5), 20m (n=4), 24m (n=5), and 28m (n=5)]. Samples chosen for immunostaining were randomly chosen by a researcher blinded to the ABR results. Confocal microscopy was used to identify the 2, 4, 12, and 24 kHz regions using low magnification 10× images and a rat cochleogram (Viberg and Canlon 2004). In each frequency region, 100× z-stack images were taken for quantification of synapses and 40× z-stacks were taken for quantification of HCs. IHC-SGN synapses (containing both pre- and post-synaptic components) and orphan synapses (containing only the presynaptic protein) were quantified in seven IHCs in each frequency region. HC quantification was counted in a 200 μm segment for each frequency region. For each set of counts, the N value represents an individual animal. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 (San Diego, CA). Percent of lifespan for FBN rats was calculated using survival data provided by the NIA aged rodent colony handbook which was based on Turtutto et al., (1999).

3. Results

In auditory studies, ABR wave I is thought to represent the far-field response from the acoustic nerve, and to be an accurate reflection of the magnitude of synchronized peripheral input to brainstem auditory structures. Later ABR waves IV/V [from pre-Inferior Colliculus (IC) and IC] likely reflects time-locked peripheral excitatory input and a combination of synchronized ascending excitatory activity in homeostatic balance with inhibitory events. With aging, the later ABR waves reflect an age-related compensatory down-regulation of brainstem inhibitory function in response to the age-related loss of peripheral input (Caspary, Ling et al. 2008, Roberts, Eggermont et al. 2010, Auerbach, Rodrigues et al. 2014, Gold and Bajo 2014).

3.1 ABR measurements

The present study examined wave I ABR thresholds and latencies across four age groups of FBN rats. All groups showed shallow “U” shaped ABR audiometric thresholds (Figure 1), similar to those seen in other rodent ABR threshold studies (Kelly and Masterton 1977, Borg 1982, Heffner, Heffner et al. 1994). For 4–6m old FBN rats, click stimuli had the lowest threshold (23.6 ± 1.2 dB) compared to other frequencies tested. Lowest threshold among pure tone frequencies was at 12 kHz (29.4 ± 2.6 dB), with higher thresholds at 4 and 24 kHz (45.6 ± 3.1 dB and 46.7 ± 3.1 dB, respectively), and highest threshold at 2 kHz (61.3 ± 3.0 dB) (Figure 1). There was an expected, significant, and progressive age-related increase in thresholds for clicks and all frequencies (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the individual differences among the different age groups. Statistical differences were found between the 4–6m and the 24m groups for clicks (p < 0.05), 2 kHz (p < 0.05), 4 kHz (p < 0.05), and 12 kHz (p < 0.01), with no differences at 24 kHz. Significant differences were also seen between the 4–6m and 28m old groups for all frequencies tested (Table 1, p < 0.01). Data also indicate a trend of age differences at 20m (p = 0.055) in response to click, but frequency specific changes were not detected until 24m in FBN rats (Table 1).

Figure 1.

ABR thresholds of FBN rats increased with age. All groups showed lowest threshold at 12 kHz. Significant differences were detected between groups for click (two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s posthoc test, p < 0.001) and all frequencies tested (p < 0.001 for 2 kHz, 4 kHz, and 12 kHz; p < 0.01 for 24 kHz). N = 9 (4–6m), 9 (20m), 8 (24m), 7(28m). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.01. Detailed between group comparisons (Table 1).

Table 1.

Wave I Threshold comparison among different age groups

| P value | Click | 2K | 4K | 12K | 24K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Paired comparison by Tukey’s posthoc test | 4–6m vs 20m | 0.055Δ | 0.830 | 0.542 | 0.472 | 0.798 |

|

| ||||||

| 4–6m vs 24m | 0.015* | 0.021* | 0.044* | 0.003** | 0.18 | |

|

| ||||||

| 4–6m vs 28m | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.002** | |

|

| ||||||

| 20m vs 24m | 0.899 | 0.105 | 0.463 | 0.101 | 0.595 | |

|

| ||||||

| 20m vs 28m | 0.001** | 0.001** | 0.002** | 0.002** | 0.017* | |

|

| ||||||

| 24m vs 28m | 0.001** | 0.078 | 0.084 | 0.346 | 0.234 | |

|

| ||||||

| ANOVA | Total |

F(3,29) = 24.12 4.96e-08*** |

F(3,28) = 12.46 2.342e-05*** |

F(3,29) = 9.95 0.0001*** |

F(3,29) = 11.71 3.375e-05*** |

F(3,29) = 5.96 0.0027** |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p value very close to statistical significant; two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test.

Age-related changes were seen in the shape of the ABR waveforms. Figure 2A shows exemplar 12 kHz evoked ABR waveforms from a 4–6m and a 28m old FBN rat. Note the significant overall decrease in waveform amplitude between young and aged ABRs (Figure 2A). Wave I ABR amplitudes between different ages of FBN rats are summarized in Figure 2B. Significant, progressive age-related decreases were found across ages for click evoked wave I ABR amplitudes (two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test, p < 0.001) (Figure 2B, Table 2). Pure-tone evoked ABRs showed smaller amplitude changes, but statistically significant differences were still detected in all frequencies tested at 28m (Figure 2B, Table 2, two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test, p < 0.05 for 4 kHz and 24 kHz, p < 0.01 for 12 kHz). Similar to wave I click-evoked amplitude changes, click-evoked wave V ABR waveforms showed significant decreases with age (Figure 2C, Table 3, two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test, p < 0.01). No age-related changes in pure tone-evoked wave V amplitude were noted across the frequencies investigated (Figure 2C, Table 3). Relatively unchanged wave V amplitudes and significantly decreased wave I amplitudes resulted in a significant increase in the wave V/I ratios. Significant age-related increases (group main effect) in the V/I ratio were found for click-evoked ABRs and for 2 kHz, 4 kHz, and 24 kHz (Figure 2D, Table 4, two-way ANOVA, p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

ABR waveform amplitudes of FBN rats at four ages. (A) Sample ABR waveforms elicited by 12 kHz at 80 dB from a young (4–6m) and an aged (28m) rat. Decreased amplitude of all waves was detected when comparing waveforms between young and aged rats. Arrows indicated the peak (P) and trough (N) measurements of wave I (P1, N1) and V (P5, N5) for the young animal waveform. (B, C) Wave I and V amplitudes from click, 2 kHz, 4 kHz, 12 kHz, and 24 kHz for the four age groups (no data from 28m at 2 kHz presented due to the high threshold of the aged rats), respectively. There were significant age-related differences in wave I amplitudes for click (p < 0.001), 2 kHz (p < 0.05), 4 kHz (p < 0.05), 12 kHz (p < 0.01), and 24 kHz (p < 0.05). Wave V amplitude remained relatively less changed except for the click evoked response (p < 0.01). There was a p = 0.05 decrease at 12 kHz among four groups. (D) Wave V/I amplitude ratio for click, 2 kHz, 4 kHz, 12 kHz, and 24 kHz from the four age groups. Wave V/I ratio for 12 kHz showed no age-related change. There were significant age-related increases in the wave V/I ratios for click, 2 kHz, 4 kHz, and 24 kHz (p < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.01. N = 9 (4–6m), 9 (20m), 8 (24m), 7(28m). Detailed group comparisons (Tables 2–4).

Table 2.

Wave I amplitude comparison among different age groups

| P value | Click | 2K | 4K | 12K | 24K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Paired comparison by Tukey’s posthoc test | 4–6m vs 20m | 0.0030** | 0.04525* | 0.7451 | 0.2468 | 0.6660 |

|

| ||||||

| 4–6m vs 24m | 0.0010** | 0.08381 | 0.0864 | 0.0111* | 0.09522 | |

|

| ||||||

| 4–6m vs 28m | 0.0010** | N/A | 0.0115* | 0.0065** | 0.0252* | |

|

| ||||||

| 20m vs 24m | 0.2698 | 0.8999 | 0.4356 | 0.4455 | 0.5410 | |

|

| ||||||

| 20m vs 28m | 0.0018** | N/A | 0.0915 | 0.2997 | 0.2178 | |

|

| ||||||

| 24m vs 28m | 0.0940 | N/A | 0.7607 | 0.8999 | 0.8999 | |

|

| ||||||

| ANOVA | Total |

F(3,27) = 21.02 3.1325e-07*** |

F(2,18) = 4.04 0.0356* |

F(3,29) = 4.53 0.0101* |

F(3,29) = 5.59 0.0038** |

F(3,29) =3.72 0.0222* |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test.

Table 3.

Wave V amplitude comparison among different age groups

| P value | Click | 2K | 4K | 12K | 24K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Paired comparison by Tukey’s posthoc test | 4–6m vs 20m | 0.1539 | 0.8999 | 0.8283 | 0.4493 | 0.5543 |

|

| ||||||

| 4–6m vs 24m | 0.0090** | 0.1386 | 0.2456 | 0.0857 | 0.8999 | |

|

| ||||||

| 4–6m vs 28m | 0.0040** | N/A | 0.1448 | 0.0714 | 0.3327 | |

|

| ||||||

| 20m vs 24m | 0.5335 | 0.1647 | 0.6645 | 0.7209 | 0.6818 | |

|

| ||||||

| 20m vs 28m | 0.2335 | N/A | 0.4847 | 0.6440 | 0.8999 | |

|

| ||||||

| 24m vs 28m | 0.8676 | N/A | 0.8999 | 0.8999 | 0.4556 | |

|

| ||||||

| ANOVA | Total |

F(3,27) = 6.27 0.0023** |

F(2,18) = 2.47 0.1124 |

F(3,29) = 2.11 0.1210 |

F(3,29) = 2.92 0.0508Δ |

F(3,29) = 1.38 0.2693 |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p value very close to statistical significant; Two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test.

Table 4.

Wave V/I ratio comparison among different age groups

| P value | Click | 2K | 4K | 12K | 24K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Paired comparison by Tukey’s posthoc test | 4–6m vs 20m | 0.8999 | 0.41 | 0.8999 | 0.8999 | 0.8999 |

|

| ||||||

| 4–6m vs 24m | 0.8548 | 0.0291* | 0.8770 | 0.8999 | 0.0555Δ | |

|

| ||||||

| 4–6m vs 28m | 0.0090** | N/A | 0.0503Δ | 0.8999 | 0.2984 | |

|

| ||||||

| 20m vs 24m | 0.8999 | 0.2516 | 0.8999 | 0.8999 | 0.0377* | |

|

| ||||||

| 20m vs 28m | 0.0357* | N/A | 0.0614 | 0.7452 | 0.2273 | |

|

| ||||||

| 24m vs 28m | 0.0500Δ | N/A | 0.22473 | 0.8999 | 0.8554 | |

|

| ||||||

| ANOVA | Total |

F(3,27) = 4.32 0.0131* |

F(2,18) = 3.98 0.0371* |

F(3,29) = 3.06 0.0437* |

F(3,29) = 0.32 0.8126 |

F(3,29) = 3.86 0.0194* |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p value very close to statistical significant; Two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test.

Analyses performed on wave I latency revealed no significant differences among the four groups (p > 0.05) or between specific group pairs, with the exception of across frequency differences between 20m and 28m old animals (two-way ANOVA, p < 0.05, data not shown).

3.2 Cochlear Pathology

After completion of ABR studies, temporal bones were collected for preparation of HC and IHC-SGN ribbon synapse quantification using immunostaining and confocal microscopy. HCs were identified using the well-characterized HC marker myosin VIIa (Hasson, Heintzelman et al. 1995) and a rat cochleogram was used to convert the 2, 4, 12, and 24 kHz regions to distance along the cochlear duct (Viberg and Canlon 2004).

Previous studies from 32m old FBN rat cochlea using a method developed by Dr. Bohne (Eldredge, Mills et al. 1973, Ou, Harding et al. 2000) described profound OHC loss and minimal IHC loss in the apical turn (Caspary, Schatteman et al. 2005, Turner and Caspary 2005). The present study done in 4–28m old FBN rats found no age-related loss of IHCs and modest OHC loss across all ages examined (Figure 3). All ages showed a well-organized organ of Corti with three rows of OHCs and one row of IHCs (Figure 3A–D). No significant change in IHC number was observed at any age or frequency distribution along the cochlea (Figure 3E). Significant age-related changes in OHC number were detected at 24m in the 2 kHz region (23.3 ± 3.3% loss) and at 28m in the 2 kHz region (29.4 ± 1.5% loss), in the 4 kHz region (12.8% ± 2.1% loss), and in the 12 kHz region (11.5% ± 1.1% loss) (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

Cytocochleogram of FBN rat cochleae at four ages. Representative maximum projection confocal images show a well-organized organ of Corti with three rows of OHCs and one row of IHCs at (A) 4–6m, (B) 20m, (C) 24m, and (D) 28m of age. HCs are labeled by myosin VIIa (myo7a, green). (E) No significant change in IHC number was observed at any age or frequency distribution along the cochlea [two-way ANOVA F (9, 45) = 1.454]. (F) Significant age-related changes in OHC number was detected at 24m in the 2 kHz region and at 28m in the 2 kHz, 4 kHz, and 12 kHz regions. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 5 for 4–6m; 4 for 20m; 5 for 24m and 5 for 28m. Two-way ANOVA [F (9, 45) = 6.698] followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test,*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

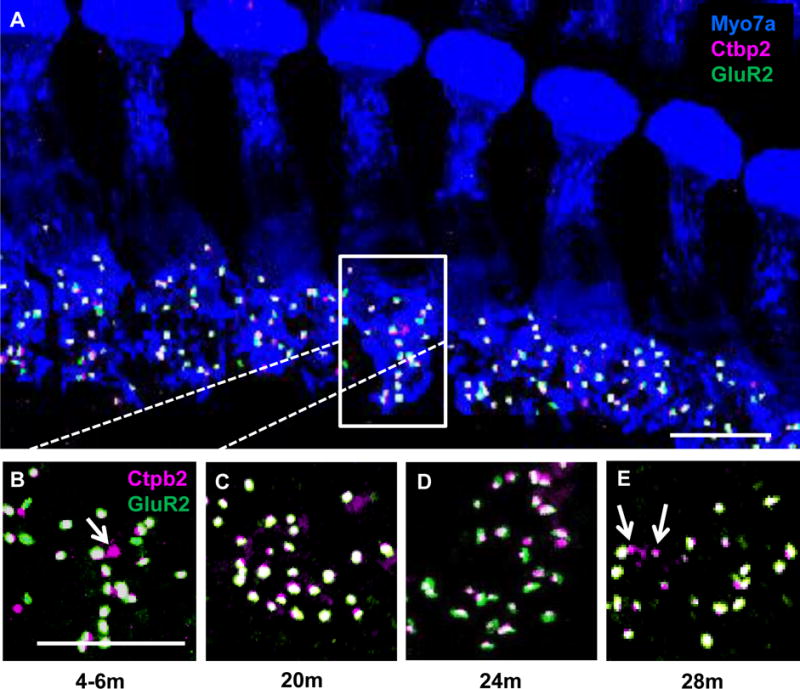

Age-related changes to IHC-SGN ribbon synapses were examined in 4–28m FBN rats using myosin VIIa to label the cytoplasm of IHCs (Figure 4A). Quantification of intact IHC-SGN synapses per IHC required the presence of both the presynaptic component (labeled by Ctbp2) and the postsynaptic component (labeled by GluR2). Quantification of orphan synapses included those with the presynaptic ribbon without an opposing postsynaptic receptor. These measurements provide a quantitative assessment of the peripheral input to the central auditory pathway.

Figure 4.

IHC-SGN synapse changes at 4 kHz in the FBN rat cochlea at four ages. Representative maximum projection confocal images showing age-related changes in synapses located on IHCs [myosin VIIa, Myo7a (blue)]. Presynaptic regions are labeled by Ctbp2 (magenta), and postsynaptic glutamate receptors are labeled by GluR2 (green). (A) Merged image showing seven IHCs from the 4 kHz region in a 4–6m rat. Box indicates synapses in one IHC, with the higher magnification image shown in (B). Representative high magnification images of IHC-SGN synapse from the 4 kHz region of 20m (C), 24m (D), and 28m (E) FBN rat cochleae. Arrows indicate orphan synapses. Scale bar in A = 10 μm and B = 5 μm.

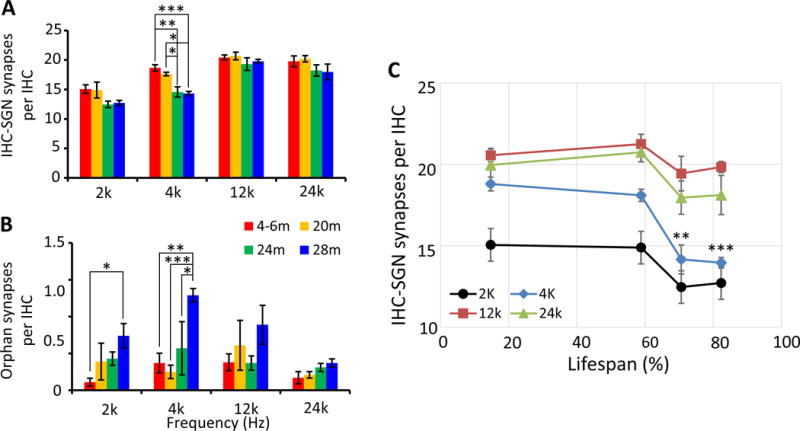

IHC-SGN synapse loss was only detected in the 4 kHz region, which correlated with significant age-related increases in ABR thresholds at 24m and 28m of age. At 4 kHz, a significant 24.7% ± 1.9% age-related loss of synapses was observed for 24m old rats with a 25.7% ± 0.7% loss seen for 28m old animals (Figures 4A–E, 5A). There was a 3.5 fold increase in orphan synapses in the 4 kHz region in 28m old rats compared to 4–6m old animals (Figure 5B). At 2 kHz, the only significant difference detected was in orphan synapses which increased 6.5 fold in 28m old rats compared to 4–6m old animals (Figure 5B). When the number of ribbon synapses was graphed as percent of lifespan, ribbon synapse loss at 4 kHz was observed at 75% of the FBN lifespan (Figure 5C) which is approximately 60 years of age in humans (Sengupta 2013).

Figure 5.

Quantification of IHC-SGN synapse number in FBN rat cochleae at four ages. Number of IHC-SGN synapses (A) and orphan synapses (B) per IHC at 2, 4, 12, and 24 kHz in FBN rats at four ages. There was a significant reduction in IHC-SGN synapses at 24m (p < 0.001) and 28m at 4 kHz (p < 0.001). In the 2 kHz region, there were significantly more orphan synapses in 28m samples compared to 4–6m (p < 0.05) samples. In the 4 kHz region, there were significantly more orphan synapses in 28m samples compared to 4–6m (p < 0.01), 20m (p < 0.001), and 24m (p < 0.05) samples. (C) The number of IHC-SGN synapses were plotted against the percentage of lifespan. Significant synapse loss was observed starting at 75% of the FBN lifespan at 4 kHz. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. N = 5 for 4–6m; 4 for 20m; 5 for 24m and 5 for 28m. Two-way ANOVA [F (9, 45) = 0.8485 for A and F (9, 45) = 1.190 for B] followed by a Tukey’s posthoc test,*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

3.3 Correlation of ABR with ribbon synapses

Since quantification of IHC-SGN ribbon synapses and HCs were performed on the same ears in a subgroup of rats that had the ABR testing (n = 4–5 for each age group), regression analyses were conducted in this matched data to determine any possible correlations among ABR wave I amplitude, ABR threshold, IHC-SGN synapse number, and HC number.

As shown in Figure 6A, significant correlations between wave I amplitudes and wave I ABR thresholds were seen across frequencies. Without dividing animals into different age groups, highly positive correlations were detected for clicks and each pure-tone frequency, with p values all less than 0.05 (Table 5, p < 0.05 for 2 kHz, p < 0.001 for click, 4 kHz, 12 kHz, and 24 kHz, Pearson correlation coefficient test). Significant positive correlations were also found between wave I amplitudes and IHC-SGN synapse number at 4 kHz (p < 0.001) and 24 kHz (p < 0.05, Pearson correlation coefficient test) for all ages (Figure 6B, Table 5).

Figure 6.

ABR wave I amplitude significantly correlates with wave I threshold and the number of IHC-SGN synapses regardless of age. (A) Negative correlations were found between wave I amplitude and ABR threshold with the highest correlation at 4 kHz (p < 0.05 for 2 kHz; p < 0.001 for 4 kHz, 12 kHz, 24 kHz and click). (B) Positive correlations were detected between wave I amplitude and the number of IHC-SGN synapses for 4 kHz (R2= 0.54, p < 0.001), 24 kHz (R2= 0.32, p < 0.05), but not 2 kHz (R2= 0.15, p = 0.21). Data were analyzed using a Pearson correlation coefficient test. N = 12 for 2 kHz, 18 for 4 kHz, 19 for 12 kHz, and 19 for 24 kHz. (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation between wave I Amplitude, ABR Threshold and IHC-SGN Synapses

| Wave I Amplitude | 2K | 4K | 12K | 24K | Click |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | R2 = 0.37, *p = 0.02708 | R2 = 0.78, ***p = 1.24E-06 | R2 = 0.68, ***p = 1.35E-05 | R2 = 0.70, ***p = 9.14E-06 | R2 = 0.61, ***p = 2.2E-04 |

| IHC-SGN Synapse | R2 = 0.15, p = 0.21 | R2 = 0.54, ***p = 5.1E-04 | R2 = 0.20, Δp = 5.8E-02 | R2 = 0.32, *p = 1.2E-02 | N/A |

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

p value very close to statistical significant. Pearson correlation coefficient test.

In addition to these correlations, we also found notable negative correlations between wave V/I ratios with OHC number at 4 kHz (Figure 7A, p < 0.001, Pearson correlation coefficient test) and wave V/I ratio with IHC-SGN synapse number at 24 kHz (Figure 7B, p < 0.001, Pearson correlation coefficient test). In the present study, no data indicated any correlation among IHC number with any ABR wave parameters (data not shown).

Figure 7.

ABR wave V/I ratio significantly correlates with OHC and IHC-SGN synapses. Correlation between wave V/I ratio and OHC numbers or IHC-SGN synapses were calculated at 2, 4, 12, and 24 kHz regardless of age. Significant negative correlations were found between wave V/I ratio and OHC numbers at 4 kHz (A) (p < 0.01, Pearson correlation coefficient test, N = 17); and between wave V/I ratio and IHC-SGN synapse number at 24 kHz (B) (p < 0.001, Pearson correlation coefficient test, N = 19).

4. Discussion

The present study found significant age-related IHC-SGN ribbon synapse loss at 4 kHz which correlated with age-related increases in wave I ABR thresholds at 24m and 28m of age. Age-related increases in ABR thresholds were also observed at 2 and 12 kHz in 24m rats and for all tested frequencies in 28m rats with no significant IHC-SGN synapse changes. Age-related loss of OHCs was detected at 24m for 2 kHz and at 28m for three frequencies, while IHCs remained intact for all frequencies regardless of age. As expected, ABR wave I amplitudes, representing the far-field response from the acoustic nerve complex, showed relatively larger age-related reductions than did the later wave V, which reflects responses from pre-IC and/or IC generators. This differential is reflected by age-related increases in the ABR wave V/I ratio. Similar to previous reports, regression analysis showed a strong correlation between IHC-SGN synapse numbers and ABR wave I amplitudes measured in the same animals (Kujawa and Liberman 2009, Sergeyenko, Lall et al. 2013, Altschuler, Dolan et al. 2015, Mohrle, Ni et al. 2016). There was little correlation between ABR wave I amplitudes and OHC counts. Together these data demonstrate that IHC-SGN synapses in the FBN rat may be more resistant to aging than in CBA/CaJ and UM-HET4 mice and female Wistar rats (Sergeyenko, Lall et al. 2013, Altschuler, Dolan et al. 2015, Mohrle, Ni et al. 2016), suggesting that there are likely species and strain differences underpinning the age of onset and magnitude of the decreased peripheral input caused by age-related IHC-SGN synapse loss.

The present study was carried out in the NIA supplied FBN F1 hybrid strain [F344 × Brown Norway (F344BN)] which has a long life span with 50% mortality at 36m of age (Lipman, Chrisp et al. 1996, Lipman 1997). This strain has been extensively used in studies of central auditory aging and has been compared with other rat models of aging (Milbrandt and Caspary 1995, Caspary, Holder et al. 1999, Caspary, Schatteman et al. 2005, Ling, Hughes et al. 2005, Turner and Caspary 2005, Turner, Hughes et al. 2005, Caspary, Hughes et al. 2006, Caspary, Ling et al. 2008, Schatteman, Hughes et al. 2008, Wang, Turner et al. 2009, de Villers-Sidani, Alzghoul et al. 2010, Hughes, Turner et al. 2010, Richardson, Ling et al. 2011, Wang, Brozoski et al. 2011, Richardson, Ling et al. 2013, Gold and Bajo 2014). The present study was driven by the need to better understand the relative timing and magnitude of the impact of aging on the auditory peripheral in the FBN rat, a strain where the impact of age-related “hidden hearing loss” has been extensively described as a compensatory loss of inhibitory function at multiple levels of the CANS (Caspary, Ling et al. 2008, Burianova, Ouda et al. 2009, Richardson, Ling et al. 2013).

Similar to previous rodent ABR threshold and aging studies, young FBN rats showed click and pure tone thresholds between 20 and 40 dB SPL with groups showing best thresholds near the rodent acoustic fovea between 12 kHz and 24 kHz (Mikaelian 1979, Hunter and Willott 1987, Caspary, Schatteman et al. 2005, Popelar, Groh et al. 2006, Bielefeld, Coling et al. 2008, Wang, Turner et al. 2009, Sergeyenko, Lall et al. 2013, Tang, Zhu et al. 2014, Altschuler, Dolan et al. 2015, Mohrle, Ni et al. 2016). Consistent with many of the rodent aging studies noted above, we found an age-related 22 dB SPL progressive parallel elevation between young (4–6m) and old (28m) rats. ABR wave I and V amplitudes progressively decreased with age with greatest changes seen for click, 2 kHz, 4 kHz, and 24 kHz (consider the V/I ratio in Figure 2D). As first suggested by Hunter and Willott and confirmed by others across species, the V/I ratio increased progressively with age and showed the largest increases for click at 80 dB SPL (Willott 1991). However, the unchanged V/I ratio suggests that 12 kHz is the frequency most likely resistant to the effects of aging.

A ~12% OHC loss was detected in cochleae from 28m old FBN rats in the 4 and 12 kHz regions. At 2 kHz, a greater OHC loss (~23%) was detected at 24m which increased to ~29% at 28m, consistent with previous studies which reported that FBN rats have severe presbycusis at low frequency regions (Keithley, Ryan et al. 1992, Caspary, Ling et al. 2008) In contrast, IHCs remained intact at all ages and for all frequency regions examined. IHC findings for FBN rats were similar to findings for Sprague-Dawley, F344, and Long-Evans rats, suggesting that aged rats maintained IHC numbers throughout their life span (Keithley and Feldman 1979, Turner and Caspary 2005, Popelar, Groh et al. 2006). However, the present study observed a far lower level of OHC loss than previously reported (Caspary, Schatteman et al. 2005, Turner and Caspary 2005). This difference may have occurred because the FBN cytocochleograms in the two earlier studies were from 32m old animals as opposed to 28m old animals in the present study. In addition, the present study used immunostaining with a known HC marker and confocal microscopy, while the previous report used an older method where HCs were identified by location and presence of a cuticular plate without the use of markers (Boettcher, Spongr et al. 1992, Spongr, Boettcher et al. 1992). It is also possible that genetic strain drift occurred between the time periods when the two FBN studies were conducted since this more commonly occurs in hybrid strains, like FBN, than in inbred strains (http://www.informatics.jax.org/nomen/strains.shtml).

IHC-SGN ribbon synapse numbers remained constant at 12 and 24 kHz across all ages examined. Yet at 4 kHz, there was a ~25% loss of synapses observed in 24m and 28m rats, as well as an increase in orphan synapses in 28m rats. There was also an increase in orphan synapses seen at 2 kHz in 28m rats. Orphan synapses, where the presynaptic ribbon is present but the postsynaptic glutamate receptor is not detected, are likely transient signs of damage. Previous studies have shown that immediately following noise exposure that induces a temporary ABR threshold shift, orphan synapses increase and then return to baseline by one week post noise (Wan, Gomez-Casati et al. 2014, Liberman, Suzuki et al. 2015, Liberman, Suzuki et al. 2015). This suggests that postsynaptic receptors degenerate first and it takes several days for the presynaptic ribbon complex to degrade. Thus, it is surprising that we were able to detect any increases in orphan synapses in the current study since no damaging insult, noise or drug, was present in these studies.

The presence of orphan synapses and the loss of paired IHC-SGN synapses suggests degeneration of SGN fibers; however, several studies have shown that it takes months to years before degeneration of SGN cell bodies is detected (Kujawa and Liberman 2009, Lin, Furman et al. 2011, Sergeyenko, Lall et al. 2013). We did not measure SGN cell bodies in the present study since all analyses were conducted on the same ear and different methods are needed for ribbon synapse and SGN quantifications. While there are no reports of SGN quantification in FBN rats, previous studies have shown different patterns of age-related SGN loss in the two parental strains of the FBN line, Brown Norway and F344 rats. Aged (36m) Brown Norway rats maintained SGNs in most frequency regions with significant (~25%) SGN loss observed in the low frequency apical region (Keithley, Ryan et al. 1992). F344 rats (aged 24–27m) showed significant loss of SGNs across frequency regions except for the apex (Keithley, Ryan et al. 1992).

Quantification of IHC-SGN synapses in the present study covered ~70% of the FBN cochlea. While previous studies have shown that FBN rats have a low frequency, apical presbycusis with little to no HC loss in basal regions (Keithley, Ryan et al. 1992, Caspary, Schatteman et al. 2005, Turner and Caspary 2005, Caspary, Ling et al. 2008), it is unknown what, if any, changes may occur in IHC-SGN synapses at frequencies higher than 24 kHz. We were not able to address this question in the present study due to technical challenges in the whole mount dissection of the basal cochlear turn.

The present ABR findings show age-related wave I amplitude and wave V/I ratio changes that correlated well with the age-related IHC-SGN synapse loss observed. This relationship between IHC-SGN synapses and ABR wave I amplitudes in the FBN rat differed from previous studies in the timing and magnitude of IHC-SGN synapse loss. Previous studies have defined “hidden hearing loss” as the loss of IHC-SGN synapses and acoustic nerve fibers with no detectable change in ABR thresholds (Liberman and Kujawa 2014). In FBN rats, IHC-SGN synapse loss was detected in one frequency region at the same age as the increase in ABR threshold for that frequency. In addition, there were no significant changes in IHC-SGN synapses at the three other tested frequencies that did show an increase in ABR threshold. However in CBA/CaJ mice, Sergeyenko et al. (2013) showed synapse loss at 32 weeks of age (~8m) at 4 kHz, with an age-related progression in severity and spread to other frequency regions, while ABR thresholds showed no change until 96 weeks of age (~22m). Similarly in UM-HET4 mice, IHC-SGN synapse loss was detected across cochlear frequency regions at 22–24m, while ABR thresholds only increased at 4 kHz at this age. The ABR thresholds later increased in all frequency regions at 27–29m. Younger ages, between 7 and 22m were not examined in UM-HET4 mice (Altschuler, Dolan et al. 2015). In female Wistar rats, only click ABRs were examined showing remarkably low, 10 dB thresholds for this rat strain. Increased thresholds were seen at 19–21m, with IHC-SGN synapse loss described in 6.5–10m old rats (Mohrle, Ni et al. 2016). These conflicting results are most likely attributable to mouse versus rat species and rat strain differences. However, age-related differences in IHC-SGN synapses and ABR thresholds may also reflect the differences in the animal facility environment, including ambient noise, vibration, and ultrasonic noise produced by ventilated cage racks and motion detectors respectively (Jeremy Turner personal communication). To better compare the percentage of synapse or cell loss between species, conversion to percent of lifespan was performed. The oldest age analyzed in the current FBN rat study was 80% of lifespan, which is comparable to 80 week old CBA/CaJ mice in the Sergeyenko et al. (2013) study. At this age there was a ~25% loss of IHC-SGN synapses in the 4 and 12 kHz regions and a ~20% loss at 30 kHz in CBA/CaJ mice, which is comparable to the ~25% loss of synapses seen at 4 kHz in FBN rats. As detailed below, the present findings in FBN rat are suggestive of complex and multiple causes of presbycusis including metabolic/strial changes, which could explain differences between the studies described above.

The causes of presbycusis were classically described by Schukenecht as resulting from four sources: sensory (loss of HCs), neural (loss of SGNs), metabolic (atrophy of the stria resulting in loss of endocochlear potential), or mechanical (stiffening of the basilar membrance or middle ear changes) (Schuknecht 1969). Later, mixed causes were also documented (Schuknecht and Gacek 1993). The observed increase in ABR thresholds in 24m and 28m old rats is only partially explained by the peripheral damage detected for OHCs and IHC-SGN synapses. The evidence of hearing loss at 12 kHz and 24 kHz in 24m and 28m old rats in the absence of IHCs, OHCs, or IHC-SGN synapse loss is suggestive of other age-related pathologies. Previous studies in quiet raised gerbils have shown an age-related degeneration of the stria vascularis, along with a decreased endocochlear potential (Schulte and Schmiedt 1992, Schulte, Muller-Schwarze et al. 1995, Gratton, Schmiedt et al. 1996). Both the FBN and F344 rat models of aging show age-related parallel shifts in their ABR threshold measures, suggestive of strial pathology (Bielefeld et al., 2010) even in the face of data suggesting age-related loss of OHCs and IHC-SGN synapses in the apical turn. The F344 rat, one of the parental strains of FBN, shows strial degeration at 24m (Buckiova, Popelar et al. 2006, Buckiova, Popelar et al. 2007), while Bielefeld et al., (2008) showed relatively minor endocochlear potential changes at this age. This suggests that metabolic changes within the stria vascularis of 24–28m old FBN rats combined with the observed low frequency OHC and IHC-SGN synapse loss may underpin the observed hearing loss.

Taken together, our data suggest that IHC-SGN synapses in the FBN rat are more resistant to aging than CBA/CaJ and UM-HET4 mice and there are likely species and strain differences underlying the cause of decreased peripheral input in age-related hearing loss. As all these studies suggest, but rarely state, the relative maintenance of the amplitude of later ABR waves likely reflects significant age-related, down-regulation of inhibitory processes in the auditory brainstem and at higher levels resulting in larger than expected super-threshold responses at multiple levels of the CANS with age (Willott, Milbrandt et al. 1997, Amenedo and Diaz 1998, Syka 2002, Caspary, Ling et al. 2008, Burianova, Ouda et al. 2009, Wang, Turner et al. 2009, Gold and Bajo 2014). This loss of inhibition, in part, underpins the loss of temporal resolving power and loss of speech understanding seen in the elderly (Bertoli, Smurzynski et al. 2002, Alain, McDonald et al. 2004, Caspary, Ling et al. 2008).

Highlights.

The FBN rat model of aging had age-related increases in ABR thresholds

ABR threshold shifts and IHC-SGN (ribbon) synapse loss were detected at the same age

Significant IHC-SGN synapse loss was only detected at 4 kHz

Outer hair cell loss was observed at 24 and 28 months in low to mid-frequency regions

Age-related reductions in ABR wave I amplitude correlated with IHC-SGN synapse loss

Wave V/I ratios increased across age, indicating central compensation

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC000151-34 to DMC); Office of Naval Research (N00014-13-1-0569 to BCC); and a SIUSOM Team Development Grant (to DMC and BCC). The SIUSOM research imaging facility equipment was supported by award number S10RR027716 from the National Center for Research Resources-Health. The authors would like to thank Dr. Thomas Brozoski for his consultation on statistical analysis. We would also like to give our special thanks to National Institute on Aging for providing the FBN rats in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alain C, McDonald KL, Ostroff JM, Schneider B. Aging: a switch from automatic to controlled processing of sounds? Psychol Aging. 2004;19(1):125–133. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler RA, Dolan DF, Halsey K, Kanicki A, Deng N, Martin C, Eberle J, Kohrman DC, Miller RA, Schacht J. Age-related changes in auditory nerve-inner hair cell connections, hair cell numbers, auditory brain stem response and gap detection in UM-HET4 mice. Neuroscience. 2015;292:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amenedo E, Diaz F. Aging-related changes in processing of non-target and target stimuli during an auditory oddball task. Biol Psychol. 1998;48(3):235–267. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(98)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach BD, Rodrigues PV, Salvi RJ. Central gain control in tinnitus and hyperacusis. Front Neurol. 2014;5:206. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2014.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertoli S, Smurzynski J, Probst R. Temporal resolution in young and elderly subjects as measured by mismatch negativity and a psychoacoustic gap detection task. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113(3):396–406. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeld EC, Coling D, Chen GD, Li M, Tanaka C, Hu BH, Henderson D. Age-related hearing loss in the Fischer 344/NHsd rat substrain. Hear Res. 2008;241(1–2):26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher FA, V, Spongr P, Salvi RJ. Physiological and histological changes associated with the reduction in threshold shift during interrupted noise exposure. Hear Res. 1992;62(2):217–236. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90189-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohne BA, Kenworthy A, Carr CD. Density of myelinated nerve fibers in the chinchilla cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 1982;72(1):102–107. doi: 10.1121/1.387994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg E. Auditory thresholds in rats of different age and strain. A behavioral and electrophysiological study. Hear Res. 1982;8(2):101–115. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(82)90069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald JS, Huang C. Far-field acoustic response: origins in the cat. Science. 1975;189(4200):382–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1145206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckiova D, Popelar J, Syka J. Collagen changes in the cochlea of aged Fischer 344 rats. Exp Gerontol. 2006;41(3):296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckiova D, Popelar J, Syka J. Aging cochleas in the F344 rat: morphological and functional changes. Exp Gerontol. 2007;42(7):629–638. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burianova J, Ouda L, Profant O, Syka J. Age-related changes in GAD levels in the central auditory system of the rat. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44(3):161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Holder TM, Hughes LF, Milbrandt JC, McKernan RM, Naritoku DK. Age-related changes in GABA(A) receptor subunit composition and function in rat auditory system. Neuroscience. 1999;93(1):307–312. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Hughes LF, Schatteman TA, Turner JG. Age-related changes in the response properties of cartwheel cells in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus. Hear Res. 2006;216–217:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Ling L, Turner JG, Hughes LF. Inhibitory neurotransmission, plasticity and aging in the mammalian central auditory system. J Exp Biol. 2008;211(Pt 11):1781–1791. doi: 10.1242/jeb.013581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Schatteman TA, Hughes LF. Age-related changes in the inhibitory response properties of dorsal cochlear nucleus output neurons: role of inhibitory inputs. J Neurosci. 2005;25(47):10952–10959. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2451-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):661–668. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.5.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Villers-Sidani E, Alzghoul L, Zhou X, Simpson KL, Lin RC, Merzenich MM. Recovery of functional and structural age-related changes in the rat primary auditory cortex with operant training. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(31):13900–13905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007885107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge DH, Mills JH, Bohne BA. Anatomical, behavioral, and electrophysiological observations on chinchillas after long exposures to noise. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1973;20:64–81. doi: 10.1159/000393089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina DR, Frisina RD. Speech recognition in noise and presbycusis: relations to possible neural mechanisms. Hear Res. 1997;106(1–2):95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina RD, Ding B, Zhu X, Walton JP. Age-related hearing loss: prevention of threshold declines, cell loss and apoptosis in spiral ganglion neurons. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8(9):2081–2099. doi: 10.18632/aging.101045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina RD, Walton JP. Age-related structural and functional changes in the cochlear nucleus. Hear Res. 2006;216–217:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman AC, Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Noise-induced cochlear neuropathy is selective for fibers with low spontaneous rates. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110(3):577–586. doi: 10.1152/jn.00164.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glowatzki E, Fuchs PA. Transmitter release at the hair cell ribbon synapse. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5(2):147–154. doi: 10.1038/nn796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JR, V, Bajo M. Insult-induced adaptive plasticity of the auditory system. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:110. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorga MP, Worthington DW, Reiland JK, Beauchaine KA, Goldgar DE. Some comparisons between auditory brain stem response thresholds, latencies, and the pure-tone audiogram. Ear Hear. 1985;6(2):105–112. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton MA, Schmiedt RA, Schulte BA. Age-related decreases in endocochlear potential are associated with vascular abnormalities in the stria vascularis. Hear Res. 1996;94(1–2):116–124. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(96)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood DD. A cochlear frequency-position function for several species–29 years later. J Acoust Soc Am. 1990;87(6):2592–2605. doi: 10.1121/1.399052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson T, Heintzelman MB, Santos-Sacchi J, Corey DP, Mooseker MS. Expression in cochlea and retina of myosin VIIa, the gene product defective in Usher syndrome type 1B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(21):9815–9819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner HE, Heffner RS, Contos C, Ott T. Audiogram of the hooded Norway rat. Hear Res. 1994;73(2):244–247. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes LF, Turner JG, Parrish JL, Caspary DM. Processing of broadband stimuli across A1 layers in young and aged rats. Hear Res. 2010;264(1–2):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter KP, Willott JF. Aging and the auditory brainstem response in mice with severe or minimal presbycusis. Hear Res. 1987;30(2–3):207–218. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerger J, Mauldin L. Prediction of sensorineural hearing level from the brain stem evoked response. Arch Otolaryngol. 1978;104(8):456–461. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1978.00790080038010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keithley EM, Feldman ML. Spiral ganglion cell counts in an age-graded series of rat cochleas. J Comp Neurol. 1979;188(3):429–442. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keithley EM, Ryan AF, Feldman ML. Cochlear degeneration in aged rats of four strains. Hear Res. 1992;59(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JB, Masterton B. Auditory sensitivity of the albino rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91(4):930–936. doi: 10.1037/h0077356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang NY, Rho JM, Northrop CC, Liberman MC, Ryugo DK. Hair-cell innervation by spiral ganglion cells in adult cats. Science. 1982;217(4555):175–177. doi: 10.1126/science.7089553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Adding insult to injury: cochlear nerve degeneration after “temporary” noise-induced hearing loss. J Neurosci. 2009;29(45):14077–14085. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2845-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman LD, Suzuki J, Liberman MC. Dynamics of cochlear synaptopathy after acoustic overexposure. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2015;16(2):205–219. doi: 10.1007/s10162-015-0510-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman LD, Suzuki J, Liberman MC. Erratum to: dynamics of cochlear synaptopathy after acoustic overexposure. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2015;16(2):221. doi: 10.1007/s10162-015-0510-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC. Morphological differences among radial afferent fibers in the cat cochlea: an electron-microscopic study of serial sections. Hear Res. 1980;3(1):45–63. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(80)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC. Single-neuron labeling in the cat auditory nerve. Science. 1982;216(4551):1239–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7079757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman MC, Kujawa SG. Hot Topics—Hidden hearing loss: Permanent cochlear-nerve degeneration after temporary noise-induced threshold shift. J Acoust Soc Am. 2014;135(2311) [Google Scholar]

- Lin FR, Thorpe R, Gordon-Salant S, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(5):582–590. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HW, Furman AC, Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Primary neural degeneration in the Guinea pig cochlea after reversible noise-induced threshold shift. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2011;12(5):605–616. doi: 10.1007/s10162-011-0277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling LL, Hughes LF, Caspary DM. Age-related loss of the GABA synthetic enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase in rat primary auditory cortex. Neuroscience. 2005;132(4):1103–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman RD. Pathobiology of aging rodents: inbred and hybrid models. Exp Gerontol. 1997;32(1–2):215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(96)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman RD, Chrisp CE, Hazzard DG, Bronson RT. Pathologic characterization of brown Norway, brown Norway × Fischer 344, and Fischer 344 × brown Norway rats with relation to age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51(1):B54–59. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51A.1.B54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara A, Laake JH, Davanger S, Usami S, Ottersen OP. Organization of AMPA receptor subunits at a glutamate synapse: a quantitative immunogold analysis of hair cell synapses in the rat organ of Corti. J Neurosci. 1996;16(14):4457–4467. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04457.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews G, Fuchs P. The diverse roles of ribbon synapses in sensory neurotransmission. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(12):812–822. doi: 10.1038/nrn2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikaelian DO. Development and degeneration of hearing in the C57/b16 mouse: relation of electrophysiologic responses from the round window and cochlear nucleus to cochlear anatomy and behavioral responses. Laryngoscope. 1979;89(1):1–15. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197901000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milbrandt JC, Caspary DM. Age-related reduction of [3H]strychnine binding sites in the cochlear nucleus of the Fischer 344 rat. Neuroscience. 1995;67(3):713–719. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00082-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohrle D, Ni K, Varakina K, Bing D, Lee SC, Zimmermann U, Knipper M, Ruttiger L. Loss of auditory sensitivity from inner hair cell synaptopathy can be centrally compensated in the young but not old brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;44:173–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SC, Cox BC. Whole Mount Dissection and Immunofluorescence of the Adult Mouse Cochlea. J Vis Exp. 2016;(107) doi: 10.3791/53561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser T, Brandt A, Lysakowski A. Hair cell ribbon synapses. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326(2):347–359. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0276-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller M. Frequency representation in the rat cochlea. Hear Res. 1991;51(2):247–254. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou HC, Harding GW, Bohne BA. An anatomically based frequency-place map for the mouse cochlea. Hear Res. 2000;145(1–2):123–129. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popelar J, Groh D, Pelanova J, Canlon B, Syka J. Age-related changes in cochlear and brainstem auditory functions in Fischer 344 rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(3):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BD, Ling LL, Uteshev VV, Caspary DM. Extrasynaptic GABA(A) receptors and tonic inhibition in rat auditory thalamus. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e16508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson BD, Ling LL, Uteshev VV, Caspary DM. Reduced GABA(A) receptor-mediated tonic inhibition in aged rat auditory thalamus. J Neurosci. 2013;33(3):1218–1227a. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3277-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LE, Eggermont JJ, Caspary DM, Shore SE, Melcher JR, Kaltenbach JA. Ringing ears: the neuroscience of tinnitus. J Neurosci. 2010;30(45):14972–14979. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4028-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safieddine S, Eybalin M. Co-expression of NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptor mRNAs in cochlear neurones. Neuroreport. 1992;3(12):1145–1148. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199212000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatteman TA, Hughes LF, Caspary DM. Aged-related loss of temporal processing: altered responses to amplitude modulated tones in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus. Neuroscience. 2008;154(1):329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF. Mechanism of inner ear injury from blows to the head. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1969;78(2):253–262. doi: 10.1177/000348946907800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Gacek MR. Cochlear pathology in presbycusis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102(1 Pt 2):1–16. doi: 10.1177/00034894931020S101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Woellner RC. Hearing losses following partial section of the cochlear nerve. Laryngoscope. 1953;63(6):441–465. doi: 10.1288/00005537-195306000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuknecht HF, Woellner RC. An experimental and clinical study of deafness from lesions of the cochlear nerve. J Laryngol Otol. 1955;69(2):75–97. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100050465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte BA, Muller-Schwarze D, Tang R, Webster FX. Bioactivity of beaver castoreum constituents using principal components analysis. J Chem Ecol. 1995;21(7):941–957. doi: 10.1007/BF02033800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte BA, Schmiedt RA. Lateral wall Na, K-ATPase and endocochlear potentials decline with age in quiet-reared gerbils. Hear Res. 1992;61(1–2):35–46. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(92)90034-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P. The Laboratory Rat: Relating Its Age With Human’s. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(6):624–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeyenko Y, Lall K, Liberman MC, Kujawa SG. Age-related cochlear synaptopathy: an early-onset contributor to auditory functional decline. J Neurosci. 2013;33(34):13686–13694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1783-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoendlin H. Innervation patterns in the organ of corti of the cat. Acta Otolaryngol. 1969;67(2):239–254. doi: 10.3109/00016486909125448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spongr VP, Boettcher FA, Saunders SS, Salvi RJ. Effects of noise and salicylate on hair cell loss in the chinchilla cochlea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(2):157–164. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880020051015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamataki S, Francis HW, Lehar M, May BJ, Ryugo DK. Synaptic alterations at inner hair cells precede spiral ganglion cell loss in aging C57BL/6J mice. Hear Res. 2006;221(1–2):104–118. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr A, Hamilton AE. Correlation between confirmed sites of neurological lesions and abnormalities of far-field auditory brainstem responses. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1976;41(6):595–608. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(76)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr A, Picton TW, Sininger Y, Hood LJ, Berlin CI. Auditory neuropathy. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 3):741–753. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syka J. Plastic changes in the central auditory system after hearing loss, restoration of function, and during learning. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(3):601–636. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Zhu X, Ding B, Walton JP, Frisina RD, Su J. Age-related hearing loss: GABA, nicotinic acetylcholine and NMDA receptor expression changes in spiral ganglion neurons of the mouse. Neuroscience. 2014;259:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JG, Caspary DM. Plasticity and Signal Representation in the Auditory System. J. Syka and M. M. Merzenich; New York, Springer US: 2005. Comparison of Two Rat Models of Aging; pp. 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JG, Hughes LF, Caspary DM. Affects of aging on receptive fields in rat primary auditory cortex layer V neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94(4):2738–2747. doi: 10.1152/jn.00362.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turturro A, Witt WW, Lewis S, Hass BS, Lipman RD, Hart RW. Growth curves and survival characteristics of the animals used in the Biomarkers of Aging Program. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(11):B492–501. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.b492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Drift JF, Brocaar MP, van Zanten GA. The relation between the pure-tone audiogram and the click auditory brainstem response threshold in cochlear hearing loss. Audiology. 1987;26(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viberg A, Canlon B. The guide to plotting a cochleogram. Hear Res. 2004;197(1–2):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan G, Gomez-Casati ME, Gigliello AR, Liberman MC, Corfas G. Neurotrophin-3 regulates ribbon synapse density in the cochlea and induces synapse regeneration after acoustic trauma. Elife. 2014:3. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Brozoski TJ, Ling L, Hughes LF, Caspary DM. Impact of sound exposure and aging on brain-derived neurotrophic factor and tyrosine kinase B receptors levels in dorsal cochlear nucleus 80 days following sound exposure. Neuroscience. 2011;172:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Turner JG, Ling L, Parrish JL, Hughes LF, Caspary DM. Age-related changes in glycine receptor subunit composition and binding in dorsal cochlear nucleus. Neuroscience. 2009;160(1):227–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson TT, Zhu X, Walton JP, Frisina RD. Auditory brainstem gap responses start to decline in mice in middle age: a novel physiological biomarker for age-related hearing loss. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;361(1):359–369. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF. Aging and the auditory system: anatomy, physiology, and psychophysics San Diego, CA, Sigular Pulishing Group, Inc 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF, Milbrandt JC, Bross LS, Caspary DM. Glycine immunoreactivity and receptor binding in the cochlear nucleus of C57BL/6J and CBA/CaJ mice: effects of cochlear impairment and aging. J Comp Neurol. 1997;385(3):405–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]