Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease and is associated with the worldwide epidemics of obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. NAFLD ranges from benign fat accumulation in the liver (steatosis) to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and cirrhosis which can progress to hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure. Mass spectrometry and magnetic resonance spectroscopy-coupled stable isotope-based flux studies provide new insights into the understanding of NAFLD pathogenesis and the disease progression. This review focuses mainly on the utilization of mass spectrometry-based methods for the understanding of metabolic abnormalities in the different stages of NAFLD. For example, stable isotopes-based flux studies demonstrated multi-organ insulin resistance, dysregulated glucose, lipids and lipoprotein metabolism in patients with NAFLD. We also review recent developments in the stable isotope-based technologies for the study of mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and fibrogenesis in NAFLD. We highlight the limitations of current methodologies, discuss the emerging areas of research in this field, and future directions for the applications of stable isotopes to study NAFLD and its complications.

Keywords: stable isotopes, citric acid cycle, fatty acid oxidation, oxidative stress, fibrosis, NAFLD

I. Introduction

The worldwide epidemic of obesity has resulted in an outbreak of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) which is the most common chronic liver disease in the United States and becoming a worldwide issue. According to recent estimates, NAFLD currently affects one third of the adult population, which is expected to produce severe economic, social and medical burdens. NAFLD involves a continuous perturbation in liver physiology and metabolism that starts with simple steatosis (fat accumulation in the liver) and may silently progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and fibrosis, eventually leading to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (Marengo, Jouness, & Bugianesi, 2016). The progressive nature of this disease has made NAFLD the second highest cause of liver transplantation. While simple steatosis can be reversed with lifestyle interventions that typically include a low-calorie diet, and exercise, currently there is no established therapy to treat NASH which affects 2–12% of the general population (National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2012; Wanless & Lentz, 1990; Williams, et al., 2011), 10–37% of obese individuals (Harnois, et al., 2006; Machado, Marques-Vidal, & Cortez-Pinto, 2006; Shalhub, et al., 2004; Wanless & Lentz, 1990), and over 60% of diabetics (Gupte, et al., 2004; Prashanth, et al., 2009). Because there is a poor understanding of disease progression and since we have a general lack of reliable therapies, NASH is associated with significant morbidity and mortality that requires special attention (McCullough, 2002; Sunny, Bril, & Cusi, 2016; Wieckowska, McCullough, & Feldstein, 2007).

One of the major road blocks in NAFLD therapy is related to the fact that currently there are no reliable non-invasive methods or biomarkers to differentiate various stages of NAFLD nor to assess the clinical response to a therapeutic intervention. Liver function and injury are currently evaluated using crude serum parameters that reflect biosynthetic function of the liver (prothrombin, albumin), hepatocellular damage (ALT, AST), detoxification (ammonia) and excretion (bilirubin). Although ultrasound and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) techniques are widely used to assess the hepatic fat content, there is still no non-invasive method to reliably characterize hepatic inflammation, ballooning and fibrosis. Histological evaluation of a liver biopsy is considered a “gold standard” for the diagnosis and staging of NAFLD. This invasive test can be associated with a number of the complications and is not a preferable test option for repeat assessments that are critically needed to evaluate therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, due to the anatomic heterogeneity of liver fibrosis, the biopsy is subject to significant sampling variability. Recently, several non-invasive approaches have been used to assess the hepatic fibrosis (Ajmera, et al., 2017; Goh, et al., 2016). In particular, the vibration controlled, transient elastography (FibroScan) and magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) have been applied to assess liver stiffness (Loomba, et al., 2014). Different circulatory mediators of oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis and apoptosis in association with liver histology have been used to identify markers of the disease activity and severity in patients with biopsy-proven NAFLD (Ajmera, et al., 2017; Soga, et al., 2011; Wieckowska, et al., 2006). Among them, several serum biomarkers panels, including cytokeratin 18 (Wieckowska, et al., 2006), FibroTest (Poynard, et al., 2012), and Fibrosis-4 (Dowman, Tomlinson, & Newsome, 2011) have been shown to have good correlations with the histological assessment of fibrosis. Still, there are currently no established biomarkers that could be used as a surrogate index of liver histology for non-invasive staging of NAFLD. In addition, existing test methods have limited use in understanding the mechanisms of the disease progression. It is also not clear why only a subset patients develop severe forms of NAFLD. Furthermore, about 20% of patients diagnosed with NASH are “fast progressers”, who advance to cirrhosis within 10 years (Singh, Khera, Allen, Murad, & Loomba, 2015). Since the heterogeneity in NAFLD progression is not always clear, a better understanding of the mechanisms of disease pathogenesis and risk factors associated with the severity of the disease could help assess risk stratification and treatment options for patients with NAFLD.

Stable isotope-based flux studies have been used to investigate different aspects of metabolic alterations in NAFLD and diseases progression. The objective of this brief review is to highlight the utility of stable isotope-based mass spectrometric methods to metabolic studies in patients with NAFLD, we also consider the existing challenges in the field.

II. Methodology

Definitions used in stable isotope-based flux studies

Before we discuss the instrumentation and biological application of stable isotopes in NAFLD research, we briefly explain terminology related to the use of stable isotopes. Molecules with a different distribution of stable isotopes are isotopomers, which can be differentiated by position and/or mass. Positional isotopomers, or structural isotopomers, have identical isotopic composition but distinct location of the heavy isotope(s) in the molecule. Mass isotopomers, also called isotopologues, are molecules that differ in the number of heavy isotopes resulting in a mass spectrum with a monoisotopic peak (M0) followed by distinct heavy isotopomer (Mi, where i is an integer > 0) peaks. For instance, [1-13C]acetate and [2-13C]acetate are positional isotopomers, while [1,2-13C]acetate and [1-13C]acetate (or [2-13C]acetate) are mass isotopomers.

Instrumentation

One of the critical steps in flux studies is the accurate measurement of the labeling pattern of metabolites based on their isotopomer distribution. There are two major technologies which are used to quantify isotopomers including magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. Stable isotope measurements with MRS provide information on both the magnitude of isotope enrichment and the positional enrichment in the molecule. In addition, MRS offers easy sample preparation but with slower throughput analysis as compared mass spectrometry-based techniques. The high cost and lower sensitivity seem to deter more widespread use of MRS in biomedical research. Nevertheless, with the continuous advancement of the technology, MRS is considered a methodology of major importance for the non-invasive assessment of the citric acid cycle (CAC) and anaplerotic fluxes (discussed below). In contrast, the higher sensitivity in combination with easier availability seems to have allowed mass spectrometry to become a technique of choice for stable isotope-based metabolic labeling studies. It is important to emphasize that in many cases these two methodologies complement each other. In this review, we will mainly focus on mass spectrometry-based flux studies and briefly mention MRS-based studies related to hepatic mitochondrial metabolism in NAFLD.

Basic principles of mass spectrometry-based flux studies

Since the invention of the first mass spectrometer, it became clear that mass spectrometry can detect different masses for the atoms of the same element. Later, it was recognized that the differences in atomic mass of the same element are determined by the distinct number of neutrons, defined as the isotopes of the element. With the technological advancements in the synthesis of stable isotope-containing molecules and mass spectrometry technology, the stable isotopes found extensive application in metabolic flux studies. Contemporary mass spectrometers offer a femtomole detection limit while chromatographic inlets enable high throughput online separation of metabolites from interfering signals; the critical factors in stable isotope-based flux studies. In addition the capability of performing tandem mass analysis, i.e. isolation and selective fragmentation of ions, provides the information on the positional isotopomer labeling. Thus, mass spectrometers allow accurate quantification of metabolite levels, mass isotopomer distribution, and, in some circumstances, can provide information on positional isotopomers.

Theoretically, the mass isotopomer distribution of a molecule is determined based on the frequencies of individual isotopes in the molecule, and can be predicted by combinatorial probability analysis. For example, one can easily calculate the baseline mass isotopomer distribution of molecule from its empirical formula and known values of heavy isotope contents in the nature. By comparing the predicted and the experimentally measured basal mass isotopomer distributions one can confirm the identity of metabolites of interest and ensure the absence of interfering signals that may affect the mass isotopomer distribution analysis.

In general, stable isotopes have been used in 2 types of flux studies: metabolic labeling and isotope dilution. The temporal changes in the isotope content of metabolites in a biosynthetic pathway or isotope dilution by the endogenously produced metabolites during the steady-state isotope infusion allow tracing and quantification of the flux in the pathway of interest. In metabolic labeling studies, the stable isotope containing precursor is incorporated into the biological product that results in an increased proportion of the heavy isotopomers in the mass isotopomer distribution envelope. Quantification of mass isotopomers is performed based on the intensity of each isotopomer of a given chromatographic peak within a defined mass range (for example Mi±0.1 m/z in GC-MS). Thus, the temporal change in the isotope content of metabolites in biosynthetic pathway allows tracing and quantification of the pathway of interest. The metabolic labeling-based fractional synthesis rate (FSR, pool−1)) of the product is calculated based on the precursor and product relationship. Thus, in a short-term labeling experiment, the FSR is derived from the ratio of pseudo-linear change in a product labeling and steady-state precursor labeling:

| (1) |

In a long-term experiment, the FSR is determined by assuming a one-compartment model and then fitting a time course labeling of a product [Epeptide (t)] into the mono-exponential rise-to-plateau curve (Kasumov, et al., 2013):

| (2) |

where, Ess is the plateau labeling of a product and k is the FSR.

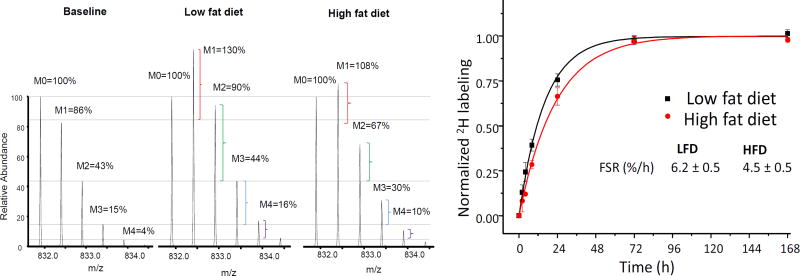

Although the latter model does not require the precursor enrichment, it does necessitate the collection of multiple samples to estimate the plateau labeling of a product (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

High resolution spectra of ApoB100 peptide in mouse plasma (A). The horizontal lines are added to aid the visualization of the changes in the isotope distribution. The natural isotope distribution of ApoB100 peptide (Baseline) in a control mouse on low fat diet before D2O administration. Changes in isotope destitution with increase in heavy isotopomers in a mouse on low fat diet and high fat diet after 72 hr of D2O intake reflect protein synthesis from 2H-labeled amino acids. Note that the magnitude of 2H-incorporation in the mice on a high fat diet is lower than control, indicating reduced turnover rate of ApoB100 which is calculated after the fitting the data to mono-exponential rise-to-curve, equation 2 (B).

In an isotope dilution experiment, the stable isotope-labeled metabolite is infused at a constant rate and the isotope dilution due to the endogenous production of this metabolite reflects its synthesis rate. In this case, the rate of appearance (Ra, µmol/kg/h) of a metabolite is calculated using the tracer dilution equation:

| (3) |

where I is rate of a tracer infusion (µmol/kg/h), EI and Ep are the enrichments (%) of the tracer in the infusate and plasma, respectively.

Thus, flux studies using stable isotope-labeled tracers measure the isotope enrichment in the products of interest which is determined by the precursor tracer enrichment and the rate of the metabolic pathway.

Choice of the tracer

When planning the tracer experiment, one needs to carefully select an appropriate tracer to address a biological question of interest. The critical factors that influence the choice of a tracer are: (i) the route of tracer administration, (ii) analytical utility, (iii) interpretation of the results, and (iv) the cost of the study. 13C, 2H, and 15N are commonly used tracers to study intermediary metabolism. Each of these tracers has advantages and disadvantages. 15N tracers have been used to study the urea and amino acid kinetics, though the transamination-induced loss of α-amino group in amino acids limits the latter applications. Because of the stability and resistance to non-enzymatic transformations, 13C-labeled tracers are extensively used in metabolic flux studies. 13C-stable isotope based tracer experiments have been carried out to study mitochondrial oxidative metabolism, including CAC and anaplerosis, fatty acid synthesis/oxidation (Bederman, et al., 2004; Kasumov, et al., 2005), glucose production/utilization (Chandramouli, et al., 1997; Wolfe, Allsop, & Burke, 1979), and protein turnover (Claydon & Beynon, 2012; Vukoti, et al., 2015). In many cases, 13C-labeled tracers require in-patient tracer administration. Although 13C tracers can be administered orally, they are subject to diet-induced metabolic fluctuations and it requires the large quantities of an expensive tracer. In addition, the kinetic analysis for each metabolite requires its own individual tracer. 13C-labeled compounds, specifically [U-13C] tracers can become expensive for large animal and human studies. In addition, administration of 13C-tracers may alter metabolic pathways via increased metabolites levels. Finally, problems associated with the data interpretation related to the difficulties in the true precursor enrichment assessment and in some cases the tracer recycling limits application of 13C-tarcers.

2H-Labeled glucose, fatty acids, amino acids and other tracer have been used as alternative low cost tracers in metabolic studies. One of the problems associated with these tracers is the potential loss of 2H during non-enzymatic reactions (e.g. in acetoacetate keto-enol tautomerization) and/or multiple enzymatic reactions (e.g. transamination). On the other hand, when 2H2O used as a tracer precursor, it rapidly labels all metabolic precursors for the synthesis of biopolymers, i.e. amino acids for proteins, deoxyribose for DNA, acetyl-CoA/NADPH for fatty acid and cholesterol, glycerol for the glycerides, and phosphoenolpyruvate/CAC intermediates for glucose synthesis. This has encouraged investigators to consider 2H2O as an alternative tracer for the synthesis of numerous small and large biomolecules. In addition, the 2H2O approach has major methodological advantages over other stable isotope methods based on metabolites pre-labeled with 2H, 13C or 15N. Specifically, multiple copies of 2H from 2H2O are transferred to the end products which increases the enrichment of newly synthesized molecule to a far greater extent than can be achieved by other tracers. This aspect can improve the assay accuracy because of the higher 2H-enrichment in analytes. The study design for heavy water-based turnover studies is relatively simple. As a safe and low-cost tracer, it can be given to free-leaving subjects, including humans by multiple oral doses over the course of a day in drinking water and does not require an intravenous infusion. In contrast to other tracers, 2H2O rapidly equilibrates with the total body water in all organs and organelles. Thus, oral administration of heavy water after a bolus load easily maintains a steady- state labeling of total body water for prolonged periods of time. Easy access to body water for 2H2O enrichment assay eliminates problems related to true precursor enrichment measurement that important for data interpretation (Wilkinson, et al., 2014). The major drawback of 2H2O utilization as a tracer is related to the fact it can be used to study only biosynthetic pathways but not for the analysis of substrate oxidation and CAC and anaplerosis flux. Despite these limitations, 2H2O has been extensively used to study glucose, fatty acid, triglyceride, and cholesterol and protein kinetics in patients with NAFLD and other diseases.

III. Flux Studies in NAFLD

Overview of NAFLD pathogenesis and disease progression

The liver plays a central role in whole organ energy metabolism. As the major site of lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis, the liver regulates glucose and lipid metabolism. Since amino acid catabolism provides a carbon source for gluconeogenesis, the liver also is involved in amino acid and protein metabolism (Newgard, 2012). NAFLD is the most common cause of perturbations in hepatic intermediary metabolism that may result in liver dysfunction. Although the precise factors that contribute to NAFLD are unknown, insulin resistance is considered to be a major underlying cause that initiates steatosis through multiple mechanisms (Goh & McCullough, 2016). In physiological conditions insulin regulates the supply of fatty acids to the liver and affects the balance between their oxidation and esterification in the liver (Gibbons, Islam, & Pease, 2000; Randle, Garland, Hales, & Newsholme, 1963). With the development of insulin resistance, the regulatory role of insulin in energy metabolism is compromised.

Although insulin resistance is commonly referred to as diminished insulin–mediated glucose uptake to tissues, impaired insulin sensitivity also affects glucose production, lipolysis and lipogenesis. Liver, muscle and adipose tissue are three major insulin-sensitive organs that are affected in NAFLD. Peripheral insulin resistance-associated inhibition of glucose disposal in muscle leads to hyperglycemia that further exacerbates systemic insulin resistance. Hepatic insulin resistance results in impaired insulin-mediated suppression of glucose production. Insulin resistance in adipose tissue results in enhanced lipolysis and increased plasma free fatty acid concentration with consequent greater influx fatty acids to the liver. Fatty acid uptake by the liver is not regulated and the liver extracts 25–40% of circulating fatty acids (Basso & Havel, 1970). Paradoxically, in the insulin resistance state, hepatic de novo lipogenesis is also stimulated by increased insulin levels. In addition, increased flux of dietary fatty acids to the liver coupled with alterations in triglyceride export from the liver may be involved in the hepatic accumulation of triglycerides. Although the role of individual lipid species in insulin resistance is debated (Luukkonen, et al., 2016; Perry, Samuel, Petersen, & Shulman, 2014; Summers, 2006), it is believed that hepatic lipid accumulation plays a key role in hepatic insulin resistance (Haque & Sanyal, 2002). In addition, lipids are involved in hepatic oxidative stress via increased fatty acid oxidation and generation pro-inflammatory mediators, including ceramides that are considered as the products of fatty acid oxidation spillover (Pagadala, Kasumov, McCullough, Zein, & Kirwan, 2012). Thus, according to the current paradigm surrounding the pathogenesis of NAFLD, insulin resistance-induced lipid accumulation (steatosis) is the “first hit” while oxidative stress and inflammation provides the “second hit” that drives the progression of steatosis to NASH.

According to this concept, in the insulin resistant state, the excessive hepatic fatty acid availability overloads the capacity of the major fatty acid metabolizing pathways (mitochondrial oxidation, triglyceride synthesis and secretion). In the liver, impaired insulin sensitivity also contributes to increased hepatic oxidation of fatty acids. Increased availability of fatty acids stimulates their mitochondrial, peroxisomal and microsomal oxidation through expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α, a nuclear receptor that transcriptionally regulates genes encoding enzymes involved in fatty acids oxidation in the liver (Reddy & Rao, 2006). Stimulation of both mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial oxidation may contribute to hepatic oxidative stress and injury through increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation (Schrader & Fahimi, 2006; Tsukamoto, 2002) (Figure 2), changes in mitochondrial function (discussed below), depletion of ATP, DNA damage, alterations in protein stability, the destruction of mitochondrial membrane via lipid peroxidation and release of various cytokines resulting in progression of the disease. Thus a number of studies in animals and humans point to the central role of oxidant stress in the propagation of NAFLD (Mota, Banini, Cazanave, & Sanyal, 2016; Musso, Cassader, & Gambino, 2016).

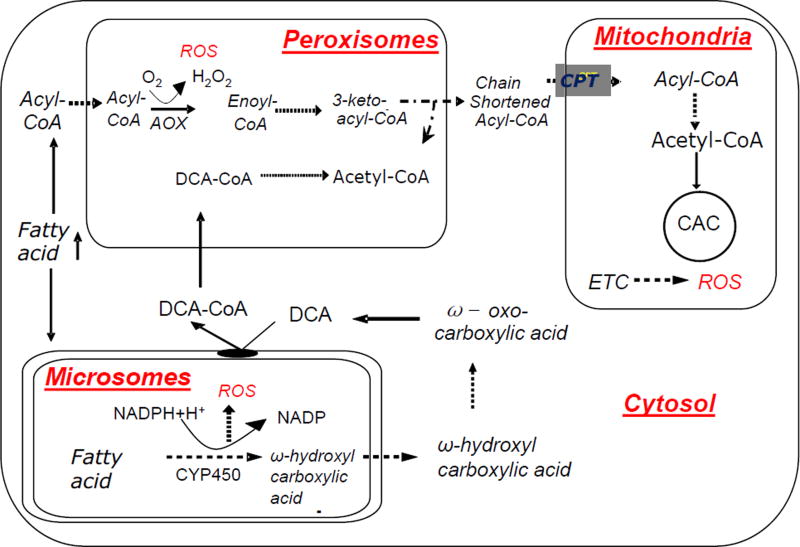

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in NAFLD. Enhanced extra-mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation is associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and it may contribute to hepatic oxidative stress in NAFLD. DCA: dicarboxylic acid, CAC: citric acid cycle, CPT: carnitine palmitoyl transferase, AOX: acyl-CoA oxidase, ETC: electron transfer chain.

Metabolic profiling has been applied to study different aspects of NAFLD pathogenesis and to stage disease progression. Although the static levels of biological biomarkers are important in the diagnosis and therapy of the disease, these measurements provide only limited insight into the mechanisms of the changes in the analyzed metabolites. The static levels of these molecules are the net results of their synthesis and degradation which are determined by the activities of connected producing/consuming enzymatic, non-enzymatic and transporting reactions. Often the magnitude of these kinetic changes surpasses the changes in static levels of these molecules, and therefore the kinetic results are more accurate indicators of physiological perturbations than simple static measurements. In addition, if both the synthesis and degradation of metabolites are equally increased or decreased, the simple measurements of their levels will not reveal any metabolic perturbations. In contrast, flux measurements – i.e. the temporal changes in metabolites, can yield an understanding of the dynamic changes in metabolic pathways. Thus, flux studies provide information on the activity of the pathway(s) that contributes to the static changes. The in vitro high-resolution respirometry (in liver biopsy samples) and in vivo splanchnic flux from hepatic vein and artery of NAFLD subjects have been used to assess hepatic substrate flux in patients with NAFLD (Hyotylainen, et al., 2016; Koliaki, et al., 2015). Although these methods are very useful in the understanding of hepatic metabolism, their invasive nature will limit their use in clinical applications. In contrast, minimally invasive stable isotope-labeled compounds are finding more practical applications in characterizing in vivo human biology by integrating physiological status/function in a time-dependent manner.

Because of the metabolic origin of NAFLD, research in this field has been mainly focused on the regulation of lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, glucose production and utilization, mitochondrial substrate oxidation, oxidative stress, and fibrosis. Stable isotopes have been used to study all of the aforementioned processes for the NAFLD diagnosis, staging, pathogenesis and progression. In contrast to radioisotopes, stable isotopes are safe to use in human studies and allow in vivo study of different pathways relevant to NAFLD pathogenesis. In this mini-review, we summarize the resent application of mass spectrometry technology-coupled with the stable isotope-based tracer methods in NAFLD research. In particular, we will review the recent literature on the application of stable isotope-based flux studies that have helped to better understand the role of insulin resistance in the initiation of steatosis, mitochondrial substrate metabolism and the role of oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and fibrosis in disease progression. We will also consider the application the stable isotope-based flux studies in disease staging with the possible assessment of hepatic fibrosis.

Insulin resistance in NAFLD

Clinically, systemic insulin resistance can be estimated based on fasting blood glucose and insulin levels or oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). However, the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp technique is considered the benchmark for the assessment of both systemic and organ-specific insulin sensitivity and resistance. This technique involves the infusion of insulin at a fixed rate while simultaneously titrating the glucose infusion to keep blood glucose levels constant (DeFronzo, Tobin, & Andres, 1979). At the steady state, the rate of glucose infusion is equal to the rate of glucose uptake by organs. Thus a greater glucose infusion rate indicates higher insulin sensitivity. Originated from radioactive tracer approach, the isotope dilution method utilizes [6,6-2H2]- or [U-13C]glucose to assess the whole body insulin resistance and hepatic glucose production. In the fasting state, the basal glucose production is calculated based on the isotope dilution approach. Under the metabolic and isotopic steady-state condition, the rate of disappearance of tracer glucose (Rd) is equal to the rate of appearance of endogenous glucose (Ra). Since Ra of endogenous glucose represents hepatic glucose production (HGP), one can calculate HGP by dividing the tracer infusion rate to the average plasma tracer-to-trace ratio (Equation 3). Glucose and insulin infusion during clamp allows assessing the hepatic insulin sensitivity to suppress HGP in response to increased insulin levels. In these non-steady states, the residual HGP is calculated by a modified version of the Steele equation (Radziuk, Norwich, & Vranic, 1978; Steele, Wall, De Bodo, & Altszuler, 1956). HGP represents the estimate of hepatic insulin sensitivity and to obtain the indices of hepatic insulin resistance, HGP needs to be related to insulin levels. Thus, based on this isotope dilution method, the level of hepatic insulin resistance is calculated as the product of HPG and corresponding insulin levels, i.e. fasting insulin or insulin levels at the plateau phase of the clamp.

While NAFLD is associated with systemic insulin resistance and skeletal muscle insulin resistance is a major component of systemic resistance to insulin action, due to prominent roles of adipose tissue and hepatic metabolism in NAFLD pathogenesis, here we will mainly focus on these two organs. The multi-stage clamp technique coupled with the combinations of [6,6-2H2]glucose or [U-13C]glucose with [2H]palmitate or [U-13C]glycerol have been used to assess simultaneously hepatic and adipose tissue muscle insulin resistance in NAFLD. After assessing the hepatic insulin resistance at the baseline (before insulin infusion), the insulin sensitivity of adipose tissue is measured by hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp technique. According to this protocol, low-dose insulin suppresses lipolysis of adipose tissue triglycerides. The rate of appearance of palmitate or glycerol is considered as an index of adipose tissue lipolysis (Korenblat, Fabbrini, Mohammed, & Klein, 2008). Thus, adipose tissue insulin resistance is determined based on the decrease in palmitate or glycerol Ra during stage 1 of a clamp (lower dose of insulin) relative to the basal state. In an elegant study, Sanyal and colleagues used [6,6-2H2]glucose and [U-13C]glycerol to assess the role of insulin resistance in the progression of NAFLD and demonstrated that NAFLD progression is associated with a gradual increase in hepatic, adipose tissue and muscle insulin resistance (Sanyal, et al., 2001). A recent study using the clamp, stable isotopes and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) microdialysis techniques confirmed that NASH patients have both hepatic and adipose tissue insulin resistance. In addition, this was the first study to demonstrate that SAT is dysfunctional in patients with NASH, suggesting the selective contribution of SAT to NASH (Armstrong, et al., 2014). Although the specific role of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) was not investigated in this study, due to VAT close proximity to the portal vein, it is believed that VAT is also an important contributor to metabolic derangements in NASH (Tordjman, et al., 2012).

Stable isotopes have been used to study the impact of steatosis on hepatic and peripheral insulin resistance (Gastaldelli, et al., 2007). For instance, [6,6-2H2]glucose in combination with 2H-palmitate infusion have been used to assess the role of hepatic fat content (measured by MRS) on hepatic, adipose tissue and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. This protocol revealed that adipose tissue insulin resistance in NAFLD patients is related to hepatic fat content, suggesting that steatosis also contributes to peripheral insulin resistance which further exacerbates NAFLD progression. The impaired insulin-induced suppression of adipose tissue lipolysis was inversely correlated with the intrahepatic triglyceride content; suggesting that NAFLD should be considered a hepatic manifestation of systemic insulin resistance.

Carbohydrate metabolism in NAFLD

The altered hepatic glucose production measurements that are described above determine the presence of hepatic insulin resistance, however, they cannot identify the mechanisms of increased glucose output in patients with NAFLD. For example, blood glucose levels are highly controlled and when the dietary glucose has been utilized, glycogen hydrolysis (glycogenolysis) and de novo glucose synthesis (gluconeogenesis, GNG) are the two pathways for glucose production. Different carbon sources, including, pyruvate/lactate and glycerol contribute to GNG. Measuring hepatic glucose production by 3H-glucose in combination with the positional 2H-enrichment analysis in glucose molecule incorporated from 2H2O in intracellular water during glucose production has been used to assess the source of blood glucose (Gastaldelli, et al., 2007). Alternatively, to avoid radioactive tracers, the combination of 2H2O with 13C-glucose was used to quantify hepatic glucose production (Jin, et al., 2015). In these studies, the relative contribution of GNG and glycogenolysis to glucose production can be determined based on the 2H-enrichments on C5 (GNG) vs C2 (GNG plus glycogenolysis) carbons of glucose (C5/C2) measured by GC-MS. The total GNG flux is calculated as the product of percentage GNG and endogenous glucose production. In addition, 2H-enrichment on C6 of glucose has been used to determine the contribution of phosphoenolpyruvate (lactate/pyruvate) to GNG (Landau, et al., 1995). The GNG from glycerol is calculated as the difference between the total GNG and GNG from lactate/pyruvate. This approach was recently used in combination with the global transcriptomic data from human liver biopsies to assess the effect of hepatic lipid content on the metabolic adaptability of the liver in substrate metabolism. It was found that increased hepatic fat content induces mitochondrial metabolism, lipolysis, glyceroneogenesis and shift in substrate selection from pyruvate to glycerol for GNG in patients with NAFLD (Hyotylainen, et al., 2016). In the early stages of insulin resistance, the tight balance between glyceroneogenesis and GNG from glycerol in patients with NAFLD maintained glycemic control at the expense of alterations in the global metabolic network. However, with the progression of insulin resistance, the metabolic adaptability is reduced and pyruvate/lactate became the major source for GNG. The authors speculate that a reduced metabolic adaptation may contribute to the co-morbidities associated with the severe forms of NAFLD. However, since this study did not differentiate steatosis from NASH, it is difficult to know whether reduced metabolic adaptation is involved in the disease progression. In contrast, despite the similar increase in GNG in patients with NAFLD in another study with the use of MRS, no selective dysregulation of individual glucose producing pathways was found (Jin, et al., 2015). The discrepancy between these results could be related to different methodologies (GC-MS vs. MRS) used in these studies.

Hepatic de novo lipogenesis and triglyceride metabolism in NAFLD

Because hepatic fat accumulation is central to both the initiation and the progression of NAFLD, one of the key end points in the evaluation of anti-NAFLD drug efficacy is hepatic fat accretion and dynamics. Hepatic fatty acid metabolism includes hepatic uptake, synthesis, oxidation and export of fatty acids. The imbalance between these processes results in triglyceride accumulation in the liver. There are three different sources of hepatic fat stores: excessive intake of dietary fat, free fatty acids derived from hydrolysis of adipose tissue and de novo lipogenesis (DNL, i.e. the biosynthesis of fatty acids from carbohydrates, ethanol and in some cases from amino acids) (Rui, 2014). In addition to hepatic lipids stores, DNL also contributes to lipid secretion by the hepatocytes. Stable isotopes have been used to quantify each of the pathways involved in hepatic lipid metabolism. Although most studies on DNL have focused on fatty acid synthesis, stable isotopes can also be applied to the study of fatty acid elongation/desaturation and triglyceride assembly (Lee, et al., 2015). In physiological conditions hepatic DNL is connected to the metabolic network involved in carbohydrate metabolism. DNL is tightly regulated at multiple levels, including transcriptional regulation of enzymes involved in the fatty acid synthesis and allosteric regulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase, an enzyme that catalyzes the production of malonyl-CoA from an acetyl-CoA precursor. Insulin and glucose transcriptionally regulate DNL by activating sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP1c) (Shimomura, Bashmakov, & Horton, 1999) and carbohydrate response element binding protein (ChREBP) (Yamashita, et al., 2001), respectively.

Existing human data suggest that DNL typically accounts for less than ~ 5% of hepatic and VLDL triglyceride content in fasted healthy subjects, this can be increased up to ~ 23% by a meal (Timlin, Barrows, & Parks, 2005). Hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia in NAFLD may transcriptionally induce DNL. Indeed, DNL is also increased under conditions associated with insulin resistance including NAFLD. In a classic study, Parks and colleagues used a multiple stable-isotope approach which ran over a 5 day labeling period to quantify the contribution of different sources of fatty acids, including DNL, to hepatic triglycerides accretion and secretion via VLDL in obese and insulin resistant patients with NAFLD who also underwent a liver biopsy for staging their condition (Donnelly, et al., 2005). The contributions of hepatic DNL and serum nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) to liver and VLDL pools were quantified using a constant infusion of [13C1]acetate and [13C4]palmitate, respectively, [2H31]glyceryl-tripalmitin was used to quantify the contribution of dietary fat. It was found that ~60% of hepatic fat was derived from NEFA, ~25% from DNL and ~15% from the diet. A similar labeling pattern of labeling was found in VLDL triglycerides (VLDL-TGs), not surprising since liver is the source of VLDL-TGs. The contribution of DNL to lipid-rich lipoproteins was not affected by fasting, indicating an insulin resistance-induced failure to respond to the nutritional state. This study design also allowed Parks and colleagues to dissect the contributions of both adipose tissue and dietary fat to serum NEFA pool which significantly changed from fasting to feeding. The adipose tissue had a higher contribution in the fasting state (~80% vs. ~60%), suggesting that adipose tissue is the major contributor of excess triglyceride accumulation in the liver. In insulin resistant states, failure of insulin to efficiently suppress the activity of hormone-sensitive lipase involved in adipose tissue lipolysis results in increased efflux of NEFA to plasma pool. This type of quantitative analysis of fatty acids sources in the liver and VLDL can be used to assess the efficacy of dietary and pharmacological interventions in NAFLD therapy.

In a follow-up study, this approach was used to compare the source of fatty acids in hepatic triglycerides in obese individuals with high versus low liver fat content (Lambert, Ramos-Roman, Browning, & Parks, 2014). The authors demonstrated that the proportion of hepatic triglycerides derived from the evening meal was not different between groups (~5%). However, the contribution of plasma free fatty acids to liver triglycerides was lower in NAFLD than compared to healthy subjects (38% vs. 52%). Interestingly, hepatic triglyceride synthesis from DNL in NAFLD group was significantly higher than in controls (23% vs. 10%). Overall, the contribution of DNL to NEFA in NAFLD was ~ 3.5-fold greater than in BMI-matched controls, clearly indicating that increased DNL is a major abnormality in NAFLD.

Stable isotopes have also been used to assess DNL based on stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1(SCD1) catalyzed palmitoleic acid (C16:1 n-7) synthesis in individuals with fatty liver (Lee, et al., 2015). Patients with increased hepatic fat content (~18%) had higher VLDL-TG palmitoleic acid compared to normal subjects. Based on the isotope incorporation data this is likely related to increased DNL, suggesting that NAFLD is also associated with increased fatty acid desaturation involved in chain elongation.

In a recent study, the 2H2O-based lipogenesis method was used in combination with 1H/13C MRS measurements of hepatic and muscle lipids to assess the role of skeletal muscle insulin resistance on hepatic DNL in elderly subjects in response to high carbohydrate feeding (Flannery, Dufour, Rabol, Shulman, & Petersen, 2012). Muscle insulin resistance was assessed based on reduced net muscle glycogen synthesis. Hyperlipidemia and hepatic steatosis in elderly subjects were associated with increased hepatic DNL suggesting that muscle insulin resistance contributes to NAFLD in elderly population through diversion of postprandial carbohydrate from glycogen storage into hepatic DNL.

VLDL-TG secretion is one of the key factors regulating of hepatic triglyceride content. Multiple stable isotope-based studies have demonstrated that VLDL-TG secretion is increased in NAFLD. Studies by Klein and his colleagues using [1,1,2,3,3-2H5]glycerol determined that VLDL-TG secretion rate was almost two-fold higher in obese patients with NAFLD than subjects with normal hepatic fat content but matched visceral adipose tissue, suggesting that intrahepatic fat, not visceral fat is linked to metabolic complications of obesity (Fabbrini, et al., 2009).

Hepatic fatty acid oxidation in NAFLD

Hepatic fatty acid oxidation-induced oxidative stress has been implicated in NAFLD progression from steatosis to NASH. Although the mitochondrion is the major organelle involved in fatty acid oxidation, both peroxisomes and microsomes also significantly contribute to fatty acid oxidation. Compared to other organs, the liver has a modest capacity for microsomal and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation. In contrast to mitochondrial oxidation, extra-mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation can operate relatively independent of the cellular energy demand. This characterizes extra-mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation as the pathways that eliminate poorly metabolized compounds, including the spillover of fatty acids. In physiological conditions, microsomal oxidation is a minor pathway of fatty acid metabolism, accounting for only ~4% of palmitate oxidation. During fasting, fat-feeding, or in pathological conditions like diabetes and inherited defects of mitochondrial β-oxidation, hepatic microsomal fatty acid oxidation increases and leads to the excretion of considerable quantities of dicarboxylic acids in urine. Microsomal fatty acid oxidation requires NADPH and O2 for ω-hydroxylation of the terminal methyl group by the cytochrome P450 (CYP 450) enzyme family, the process that is also associated with the generation of ROS. Dicarboxylic acids, generated by microsomal oxidation, are activated by microsomal membrane associated dicarboxyl-CoA synthase and are further oxidized in peroxisomes (Fig. 2). Peroxisomes are also responsible for chain-shortening of very-long-chain fatty acids, methyl-branched fatty acids and dicarboxylic acids. Although there are no in vivo measures of peroxisomal oxidation in the literature, data on isolated rat hepatocytes indicate that ~30% of palmitate oxidation is initiated in peroxisomes. The first and rate limiting step in peroxisomal β-oxidation is catalyzed by acyl-CoA oxidase (AOX) which also generates the pro-oxidant H2O2 as a side product. Thus, excessive upregulation of microsomal and peroxisomal oxidation could contribute to hepatic oxidative stress and injury in NAFLD through increased ROS generation by CYP450 and AOX, respectively (Schrader & Fahimi, 2006; Tsukamoto, 2002). However, very little is known on the partitioning of fatty acid oxidation in different organelles in NAFLD.

Because β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) is a side product of hepatic mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation, plasma concentrations of BHB have been used as an index of hepatic mitochondrial oxidation. However, as a static estimate of fatty acid oxidation, BHB levels may not reflect the NAFLD-induced changes in hepatic fatty acid oxidation and there are conflicting results in the literature in this regard. Sanyal and colleagues have shown that BHB levels are significantly higher in biopsy-proven NASH patients compared to healthy controls but not different from patients with simple steatosis (Sanyal, et al., 2001). However, no difference was found between patients with NAFLD and BMI-matched healthy controls (Kotronen, et al., 2009). It is important to note that NAFLD in these subjects was assessed based on liver fat content by MRS and it is unknown whether any of the patients had NASH. In another study a similar approach was used to assess the effect of biopsy-proven NASH on hepatic fatty acid oxidation in response to a lipid challenge through the intravenous infusion of Intralipid® with heparin. In the basal state, there were no differences in the BHB levels between patients with NASH and healthy controls, the Intralipid® infusion resulted in a significant increase of BHB in both groups (Dasarathy, et al., 2009). Based on the greater slope of the correlation between plasma free fatty acids and BHB levels in subjects with NASH, the authors concluded that hepatic mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation is increased in NASH. However, plasma levels of BHB measured in these studies reflect neither flux of BHB nor true measures of hepatic fatty acid oxidation. Therefore, more accurate stable isotope-based measurements of hepatic fatty acid oxidation are needed to assess the role of NAFLD in hepatic fatty acid oxidation. Although to the best of our knowledge, there is no stable isotope based study in patients with NAFLD, recently sex-specific differences in hepatic mitochondrial and whole body fatty acid oxidation in healthy men and women with similar liver fat content (<5%) were assessed after oral ingestion of [U-13C]palmitate. The appearance of 13C from dietary fat into BHB and CO2 was greater in women, suggesting that decreased hepatic and whole body fatty acid oxidation may explain the increased susceptibility for NAFLD in men (Pramfalk, et al., 2015).

13C-Breath tests have been used different aspects of hepatic functions, including mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (Bonfrate, Grattagliano, Palasciano, & Portincasa, 2015). The rationale is that after the oral ingestion of the 13C substrates they are primarily metabolized in the liver. The principles of the hepatic breath test concept are determined by several pharmacokinetic and metabolic factors. Thus, if the metabolic pathway is known, a substrate has a simple pharmacokinetics and short elimination half-life, and the 13CO2 generated is distributed in the whole body without compartmentalization, then the time course analysis of 13CO2 in the breath could be used to trace the activity of this pathway. For example, the 13C-octanoate breath test is commonly used to assess gastric emptying. 13C-octanate was also used to estimate mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in NAFLD (Schneider, et al., 2005; Shalev, et al., 2010). After intestinal absorption, octanoate, a medium chain fatty acid, directly enters into hepatic mitochondria independent of the carnitine palmitoyl transport (CPT) system. In the mitochondria, fatty acid β-oxidation generates acetyl-CoA that are further oxidized to CO2 in the CAC. If the intestinal absorption of octanoate is normal, then it is expected that the changes in the appearance of 13CO2 reflects the hepatic mitochondrial oxidation due to liver disease. However, so far the results of the 13C-octanoate breath test in patients with NAFLD have been mixed. Both increased and no change in the oxidation of octanoate have been reported in patients with NASH (Miele, et al., 2003; Schneider, et al., 2005), and surprisingly no differences were detected in the patients with early stage and advanced cirrhosis (van de Casteele, et al., 2003).

Unfortunately, there is a gap in the methods that are currently available, there is no established stable isotope-based method that can estimate the contribution of extra-mitochondrial oxidation of circulating fatty acids. The role of extra-mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in oxidative stress in patients with NAFLD is also unclear. Hepatic microsomal oxidation in humans has been estimated based on CYP2E1 activity measured via the generation of 6-hydroxychlorzoxazone in plasma after ingestion of chlorzoxazone (Chalasani, et al., 2003). Although CYP2E1 is a key enzyme involved in microsomal hydroxylation of fatty acids, this approach does not take into account other CYP450 enzymes catalyzing microsomal oxidation and therefore does not measure the flux of microsomal fatty acid oxidation. Although both microsomal and peroxisomal fatty acid oxidation can be measured in vitro in liver preparations and in vivo in animals using radioactive isotopes, none of these methods are applicable to human studies. Thus, there is an unmet need regarding the non-invasive quantification of mitochondrial and extra-mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in NAFLD.

Very-low density lipoprotein (VLDL) metabolism in NAFLD

Compared with carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, very little is known about the effect of NAFLD on protein metabolism. Because protein metabolism is regulated by insulin, it is expected that in NAFLD (associated with insulin resistance), hepatic protein metabolism is also could be altered. In physiological conditions, as an anabolic hormone, insulin transcriptionally promotes protein synthesis and controls nitrogen balance. However, very little is known about the effect of insulin resistance on hepatic protein metabolism. Because of its critical role in hepatic triglyceride export, protein research in NAFLD has mainly focused on ApoB metabolism. ApoB100 is synthesized in the human liver and involved in triglyceride secretion, while its truncated isoform ApoB48 is synthesized by the intestine and acts to facilitate dietary fat absorption via chylomicrons. In contrast to ApoB48, ApoB100 metabolism has been extensively studied in obesity and NAFLD to investigate both LDL and VLDL kinetics (Fabbrini, et al., 2008; Millar, et al., 2015). Co-translational lipidation of ApoB100 is facilitated by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP). In normal conditions, insulin regulates hepatic fatty acid availability and the balance between oxidation, esterification and triglyceride export with VLDL.

Insulin controls the secretion of VLDL via both triglyceride and ApoB100 metabolism. Insulin regulates VLDL secretion by decreasing ApoB100 synthesis and inhibiting the expression of MTP (Sparks & Sparks, 1990). When lipids are limiting, ApoB100 translocation is impaired because of its degradation in proteasomes. When the supply of lipids is not limiting, ApoB100 secretion is regulated by post-ER pre-secretory proteolysis (Fisher & Ginsberg, 2002). This pathway is stimulated by ROS and seems to be responsible for reduced VLDL secretion associated with oxidative stress (Brodsky & Fisher, 2008).

With the development of insulin resistance, the regulatory role of insulin in ApoB100 metabolism is disrupted (Sozio, Liangpunsakul, & Crabb). Multiple stable isotope-based studies have demonstrated that chronic hyperinsulinemia stimulates ApoB100 production and secretion of triglyceride-rich VLDL particles and it is believed that unmatched ApoB100 production and VLDL secretion results in hepatic steatosis. In particular, it has been shown that liver fat content in obese patients with NAFLD is strongly correlated with VLDL secretion rate as measured by ApoB100 labeling (Chan, et al., 2010; Sparks & Sparks, 1990; Sparks, Sparks, & Adeli, 2012), suggesting that hepatic steatosis is involved in enhanced VLDL secretion and hypertriglyceridemia. Interestingly, a low fat diet-based weight loss program resulted in both reduced liver fat content and VLDL-ApoB100 secretion indicating that weight loss-induced improvement in hypertriglyceridemia is associated with reduced ApoB100 synthesis.

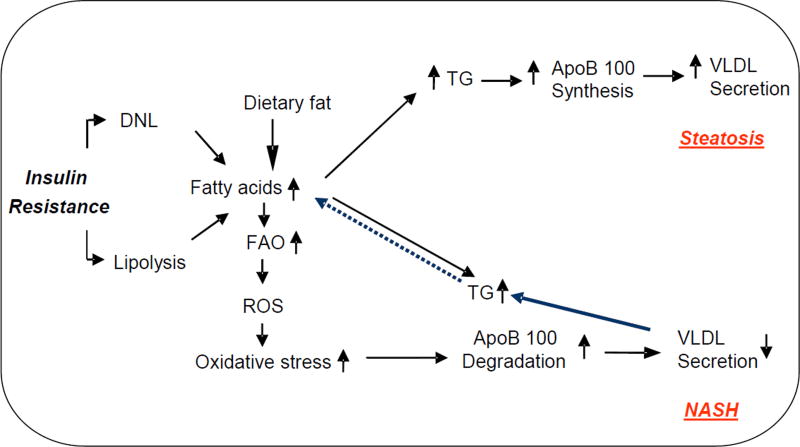

However, the published literature on VLDL secretion in patients with NAFLD has been conflicting; VLDL secretion has been reported to be increased (Fabbrini, et al., 2008), normal (Diraison, Moulin, & Beylot, 2003) and reduced (Charlton, Sreekumar, Rasmussen, Lindor, & Nair, 2002). Only one study in well characterized, biopsy-proven NAFLD patients demonstrated that ApoB100 synthesis is reduced in patients with NASH (Charlton, et al., 2002). There are also conflicting reports on the effect of 16-week exercise training in VLDL-ApoB100 kinetics. An early study demonstrated that exercise did not improve VLDL kinetics despite the beneficial effect on hepatic triglyceride content (Sullivan, Kirk, Mittendorfer, Patterson, & Klein, 2012). However, a recent study demonstrated that an exercise-induced reduction of hepatic fat content was associated with increased VLDL clearance (Shojaee-Moradie, et al., 2016). The major reason for these discrepancies is likely related to heterogeneity of the study population and the disease severity, VLDL secretion may be differentially altered by steatosis and NASH. Thus, it is plausible to propose that ApoB100 synthesis is increased in subjects with steatosis, because of an increased hepatic triglyceride production. However, an imbalance between triglyceride synthesis and secretion induces hepatic oxidative stress via fatty acid oxidation and inflammation, which may increase ApoB100 catabolism leading to the progression steatosis to NASH. Thus, it is expected that in patients with NASH, VLDL secretion is reduced because of ApoB100 degradation (Figure 3). Therefore the careful study of VLDL secretion in biopsy-proven steatosis and NASH is needed.

Figure 3.

The metabolic events leading to altered very-low density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion in NAFLD. While increased synthesis of ApoB100 leads to enhanced VLDL secretion in steatosis, oxidative stress-induced degradation of ApoB100 may result in reduced VLDL secretion in NASH. TG; triglyceride, ROS; reactive oxygen species, FAO; fatty acid oxidation.

Citric acid cycle and anaplerosis fluxes in NAFLD

Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a key role in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Data from patients with NASH show loss of hepatic mitochondrial cristae and the paracrystalline inclusion of unknown composition (Caldwell, et al., 1999; Sanyal, et al., 2001). Although biochemical mechanisms leading to these morphological lesions are unknown, these observations suggest mitochondrial damage. Furthermore, in vivo data in humans using various 13C-labeled substrates (methionine and ketoisocaproic acid) have suggested a lower rate of mitochondrial oxidation in patients with NAFLD (Banasch, Ellrichmann, Tannapfel, Schmidt, & Goetze, 2011; Portincasa, et al., 2006).

CAC plays a critical role in oxidative mitochondrial metabolism. Because of the central role of the liver in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, mitochondrial CAC and anaplerosis, an influx of metabolites into CAC, connects hepatic fatty acid and glucose metabolism. While CAC is essential in the oxidation of acetyl-CoA to CO2 and generation of reducing energy equivalents, anaplerotic fluxes sustain GNG. Attempts were made to quantify these pathways non-invasively using a chemical biopsy approach that is based on hepatic conjugation of phenylacetate with endogenously labeled glutamate, to this point this method is not been applied to NAFLD and other diseases. Instead, [2-13C]acetate and [U-13C]propionate-based magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) techniques were developed for direct non-invasive assessment of hepatic mitochondrial oxidative and anaplerotic fluxes in patients with NAFLD (Befroy, et al., 2014; Petersen, Befroy, Dufour, Rothman, & Shulman, 2016; Satapati, et al., 2015; Sunny, Parks, Browning, & Burgess, 2011). However, the contradicting results were obtained based on these two approaches. While tracing CAC flux using [U-13C]propionate-labeling of glucose shows excessive hepatic mitochondrial CAC (Sunny, et al., 2011), [2-13C]acetate-based labeling of the glutamate approach did not reveal any alterations in hepatic mitochondrial oxidation in patients with NAFLD (Petersen, et al., 2016). There are concerns related to the use of these methods. For example, metabolism of [U-13C]propionate could be affected by hepatic zonation and at higher concentrations propionate increases hepatic GNG. On the other hand, rapid extra-hepatic metabolism of [2-13C]acetate can result in significant labeling of glutamine and 13CO2 that may increase the 13C labeling of glutamate. Additional studies are needed in this area. Some hidden assumptions and practicality of different methodologies for evaluations of the fluxes through CAC and anaplerosis can be found in recent review on this topic (Previs & Kelley, 2015).

Glutathione metabolism in NAFLD

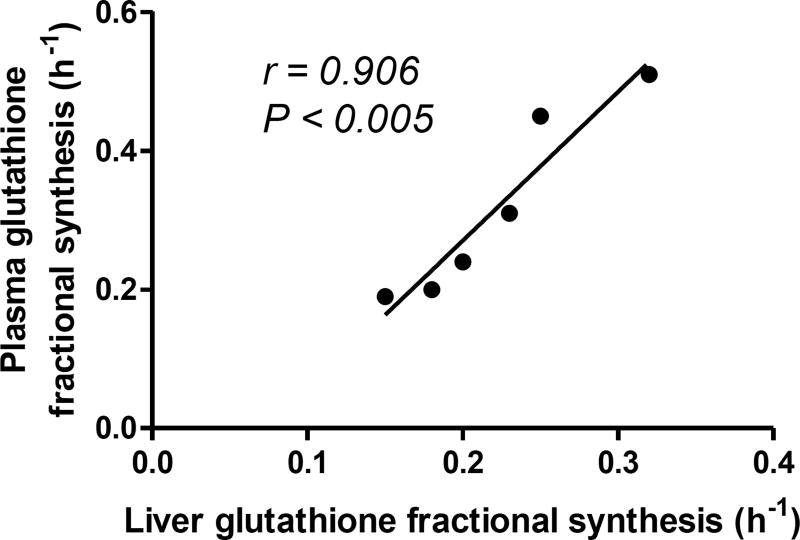

Patients with NAFLD have impaired respiratory coupling (Rector, et al., 2010) and increased NADH/NAD ratio (Satapati, et al., 2015) which may result in the reductive load of electron transport chain with consequent hepatic oxidative stress. Enhanced extra-mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation can also contribute to oxidative stress in NAFLD. Indeed, patients with NAFLD have increased levels of hepatic lipid peroxidation products (Koliaki, et al., 2015). Because of the significance of oxidative stress in NAFLD pathogenesis, there is of great interest in the non-invasive analysis of hepatic oxidative stress. Metabolomics approaches have helped identify plasma γ-glutamyl dipeptides as biomarkers of hepatic oxidative stress in NAFLD (Soga, et al., 2011). γ-Glutamyl dipeptides are derived from γ-glutamylcysteine, an intermediate in glutathione (GSH) synthesis. GSH is the major intracellular anti-oxidant tri-peptide of glutamate, cysteine and glycine, and it is synthesized from these amino acids in two steps by γ-glutamylcysteine synthase and GSH synthase. Under oxidative conditions, increased γ-glutamylcysteine synthase activity stimulates GSH synthesis via formation of γ-glutamylcysteine, the excess of which can produce γ-glutamyl dipeptides by the action of transpeptidase. Recently, hepatic glutathione synthesis was measured with [2-13C]glycine coupled with MRS. Although the feasibility of this approach in human studies was demonstrated in 3 healthy subjects, so far it has not been applied to patients with NAFLD. The low sensitivity of this method required high levels of tracer administration to achieve ~50–65% [2-13C]glycine enrichment in human plasma that resulted in a 3–5 fold increase in intracellular and plasma glycine levels (Skamarauskas, et al., 2014). Preclinical applications of this method showed increased glutathione flux in the CCl4-induced rat model of oxidative stress and NASH. Since glycine supplementation increases glutathione production (Ruiz-Ramirez, Ortiz-Balderas, Cardozo-Saldana, Diaz-Diaz, & El-Hafidi, 2014; Sekhar, et al., 2011), it is possible that this approach could overestimate the synthesis rate of glutathione. In contrast, recently based on the 2H2O-metabolic labeling approach, we demonstrated that a Western diet induced NAFLD in LDLR−/− mice was associated with reduced hepatic glutathione synthesis (Li, et al., 2016). Interestingly, NAFLD in this model also lead to impaired plasma glutathione flux that was strongly correlated with the hepatic glutathione turnover (Figure 4). Since, liver contributes to more than 90% of plasma glutathione (Lauterburg, Adams, & Mitchell, 1984), these results suggest that plasma GSH turnover could be used to non-invasively assess hepatic oxidative stress in patients with NAFLD. Studies are on the way to confirm these findings in the biopsy-proven patients with NAFLD.

Figure 4.

The fractional synthesis rate (FSR) of plasma glutathione in a diet-induced mouse model of NAFLD correlates with the FSR of hepatic glutathione.

Hepatic fibrosis in NAFLD

Enhanced fibrosis is the major characteristic of disease severity in NAFLD. Recently 2H2O metabolic labeling was applied to assess hepatic collagen synthesis in parallel with histopathologic fibrosis score in patients with chronic liver disease (Decaris, et al., 2015). The kinetics of multiple extracellular proteins, including different collagen isoforms were quantified. All extracellular proteins had higher turnover rates in subjects with increased fibrosis and the kinetics of collagen type I and VI had strongest positive correlations with histologic fibrosis. The turnover rate of plasma protein lumican, a proteoglycan involved in collagen fibrillogenesis, was correlated with the turnover rate of collagen suggesting that plasma lumican flux could be used as a “virtual biopsy” of hepatic fibrosis. Although, plasma lumican originates from multiple organs, lumican is overexpressed in the liver of patients with NASH (Charlton, et al., 2009). Based on the assumption that plasma lumican turnover may reflect haptic fibrogenesis activity, in the follow up study these authors quantified both hepatic collagen and plasma lumican kinetics with 2H2O in patients with NAFLD (Decaris, et al., 2017). Similar to an earlier study, authors found that hepatic collagen turnover increased in NASH patients with advanced fibrosis and it was correlated with plasma lumican turnover. Based on these two studies the authors propose to use plasma lumican flux as a surrogate marker of hepatic fibrogenesis.

Although the 2H2O metabolic labeling-approach is promising in regards quantification of hepatic fibrogenesis, one needs to consider several points when planning collagen turnover studies. In addition to multiple collagen isoforms, each type of collagen may form dimers, trimers and multimers. This could be associated with compartmentalization of collagen pools with different turnover rates. In addition, because of the slow turnover of collagen (02–0.6%/day) (Decaris, et al., 2015), it is critical to consider an appropriate labeling protocol to achieve “sufficient” product (collagen) labeling for accurate modeling of the data. For instance, it was recently shown that the heterogeneity in hepatic collagen pool may result in erroneous interpretations of turnover results if one does not take into account appropriate sampling time and a curve fitting model (linear vs. exponential) (Zhou, et al., 2015). Although it is always desirable to perform the turnover studies in the shortest possible time, it appears that the heterogeneity of collagen pools may require extra considerations when designing labeling protocols for accurate quantification of collagen turnover.

IV. Summary and future directions

Stable isotope-based studies have greatly contributed to our understanding of multiple aspects of NAFLD pathogenesis. Because of these studies, we now know that multi-organ insulin resistance is a major underlying mechanism of NAFLD. For example, impairments in insulin-mediated control of adipose tissue lipolysis, hepatic DNL and secretion of triglycerides all seem to contribute to steatosis. Stable isotope-based studies have also helped investigators to understand the role of altered mitochondrial metabolism in NAFLD pathogenesis. The recent studies on hepatic glutathione and collagen turnover suggest increased oxidative stress and fibrogenesis in patients with NASH. However, as we briefly discussed above, these methods need to be improved for accurate assessment of glutathione and collagen fluxes.

In addition, there are still multiple unanswered questions related to the progression of NAFLD and its complications. Particularly, there is currently no non-invasive isotope-based method for the accurate quantification of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Although extra-mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation is implicated in hepatic oxidative stress, at present, we cannot measure fluxes through individual fatty acid oxidation pathways in vivo. In contrast to VLDL, almost nothing is known about LDL and HDL metabolism in patients with NAFLD. While animal and human studies suggest that cholesterol and sphingolipids are involved in NAFLD progression detailed flux studies are missing in these areas. Although it is known that hepatic protein turnover is altered in severe liver diseases, very little is known about hepatic mitochondrial protein metabolism in NAFLD. It is also unknown how an increased lipid load and oxidative stress alters the stability and functionality of hepatic proteins involved in energy metabolism. The role of gut microbiota in NAFLD pathogenesis also requires further investigations. Last, very little is known about the effect of diet-induced epigenetic changes in NAFLD pathogenesis. Many of these questions could be investigated with stable isotopes, however, these would require further progress in mass spectrometry and MRS technology, and data modeling for accurate interpretation of stable isotope-based flux studies.

Acknowledgments

The research of TK was supported by AHA grant 15GRNT25500004 and NIH grants 1R01HL129120-01A1 and 5R01GM112044, and Northeast Ohio Medical University.

List of abbreviations

- AOX

acyl-CoA oxidase

- CAC

citric acid cycle

- DNL

de novo lipogenesis

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- FSR

fractional synthesis rate

- FT-ICR

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance

- IRMS

isotope ratio mass spectrometry

- HGP

hepatic glucose production

- GSH

glutathione

- GNG

gluconeogenesis

- GC-MS

gas chromatography mass spectrometry

- GC-C-IRMS

gas chromatography combustion isotope ratio mass spectrometry

- HPLC-MS

high-performance liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- MRE

magnetic resonance elastography

- MTP

microsomal triglyceride transfer protein

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- NEFA

nonesterified fatty acids

- OGTT

oral glucose tolerance test

- Ra

rate of appearance

- Rd

rate of disappearance

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TOF

time of flight

- SAT

subcutaneous adipose tissue

- SIM

selected ion monitoring

- VAT

visceral adipose tissue

- VLDL

very-low density lipoprotein

- VLDL-TG

VLDL triglycerides

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

TK and AM declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

SP is employed by and owns a stock in Merck.

References

- Ajmera V, Perito ER, Bass NM, Terrault NA, Yates KP, Gill R, Loomba R, Diehl AM, Aouizerat BE Network, N. C. R. Novel plasma biomarkers associated with liver disease severity in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2017;65:65–77. doi: 10.1002/hep.28776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong MJ, Hazlehurst JM, Hull D, Guo K, Borrows S, Yu J, Gough SC, Newsome PN, Tomlinson JW. Abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue insulin resistance and lipolysis in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:651–660. doi: 10.1111/dom.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banasch M, Ellrichmann M, Tannapfel A, Schmidt WE, Goetze O. The non-invasive (13)C-methionine breath test detects hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction as a marker of disease activity in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Eur J Med Res. 2011;16:258–264. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-16-6-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso LV, Havel RJ. Hepatic metabolism of free fatty acids in normal and diabetic dogs. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1970;49:537–547. doi: 10.1172/JCI106264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederman IR, Kasumov T, Reszko AE, David F, Brunengraber H, Kelleher JK. In vitro modeling of fatty acid synthesis under conditions simulating the zonation of lipogenic [13C]acetyl-CoA enrichment in the liver. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:43217–43226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Befroy DE, Perry RJ, Jain N, Dufour S, Cline GW, Trimmer JK, Brosnan J, Rothman DL, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Direct assessment of hepatic mitochondrial oxidative and anaplerotic fluxes in humans using dynamic 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Nat Med. 2014;20:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nm.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfrate L, Grattagliano I, Palasciano G, Portincasa P. Dynamic carbon 13 breath tests for the study of liver function and gastric emptying. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2015;3:12–21. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gou068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky JL, Fisher EA. The many intersecting pathways underlying apolipoprotein B secretion and degradation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell SH, Swerdlow RH, Khan EM, Iezzoni JC, Hespenheide EE, Parks JK, Parker WD., Jr Mitochondrial abnormalities in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:430–434. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalasani N, Gorski JC, Asghar MS, Asghar A, Foresman B, Hall SD, Crabb DW. Hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 activity in nondiabetic patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2003;37:544–550. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DC, Watts GF, Gan S, Wong AT, Ooi EM, Barrett PH. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as the transducer of hepatic oversecretion of very-low-density lipoprotein-apolipoprotein B-100 in obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1043–1050. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.202275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli V, Ekberg K, Schumann WC, Kalhan SC, Wahren J, Landau BR. Quantifying gluconeogenesis during fasting. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E1209–1215. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.6.E1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton M, Sreekumar R, Rasmussen D, Lindor K, Nair KS. Apolipoprotein synthesis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.) 2002;35:898–904. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton M, Viker K, Krishnan A, Sanderson S, Veldt B, Kaalsbeek AJ, Kendrick M, Thompson G, Que F, Swain J, Sarr M. Differential expression of lumican and fatty acid binding protein-1: new insights into the histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:1375–1384. doi: 10.1002/hep.22927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claydon AJ, Beynon R. Proteome dynamics: revisiting turnover with a global perspective. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:1551–1565. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O112.022186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasarathy S, Kasumov T, Edmison JM, Gruca LL, Bennett C, Duenas C, Marczewski S, McCullough AJ, Hanson RW, Kalhan SC. Glycine and urea kinetics in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in human: effect of intralipid infusion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G567–575. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00042.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaris ML, Emson CL, Li K, Gatmaitan M, Luo F, Cattin J, Nakamura C, Holmes WE, Angel TE, Peters MG, Turner SM, Hellerstein MK. Turnover rates of hepatic collagen and circulating collagen-associated proteins in humans with chronic liver disease. Plos One. 2015;10:e0123311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decaris ML, Li KW, Emson CL, Gatmaitan M, Liu S, Wang Y, Nyangau E, Colangelo M, Angel TE, Beysen C, Cui J, Hernandez C, Lazaro L, Brenner DA, Turner SM, Hellerstein MK, Loomba R. Identifying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients with active fibrosis by measuring extracellular matrix remodeling rates in tissue and blood. Hepatology. 2017;65:78–88. doi: 10.1002/hep.28860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol. 1979;237:E214–223. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1979.237.3.E214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diraison F, Moulin P, Beylot M. Contribution of hepatic de novo lipogenesis and reesterification of plasma non esterified fatty acids to plasma triglyceride synthesis during non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes & metabolism. 2003;29:478–485. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly KL, Smith CI, Schwarzenberg SJ, Jessurun J, Boldt MD, Parks EJ. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115:1343–1351. doi: 10.1172/JCI23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowman JK, Tomlinson JW, Newsome PN. Systematic review: the diagnosis and staging of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:525–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrini E, Magkos F, Mohammed BS, Pietka T, Abumrad NA, Patterson BW, Okunade A, Klein S. Intrahepatic fat, not visceral fat, is linked with metabolic complications of obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15430–15435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrini E, Mohammed BS, Magkos F, Korenblat KM, Patterson BW, Klein S. Alterations in adipose tissue and hepatic lipid kinetics in obese men and women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:424–431. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher EA, Ginsberg HN. Complexity in the secretory pathway: the assembly and secretion of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:17377–17380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery C, Dufour S, Rabol R, Shulman GI, Petersen KF. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance promotes increased hepatic de novo lipogenesis, hyperlipidemia, and hepatic steatosis in the elderly. Diabetes. 2012;61:2711–2717. doi: 10.2337/db12-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastaldelli A, Cusi K, Pettiti M, Hardies J, Miyazaki Y, Berria R, Buzzigoli E, Sironi AM, Cersosimo E, Ferrannini E, Defronzo RA. Relationship between hepatic/visceral fat and hepatic insulin resistance in nondiabetic and type 2 diabetic subjects. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:496–506. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons GF, Islam K, Pease RJ. Mobilisation of triacylglycerol stores. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2000;1483:37–57. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh GB, Issa D, Lopez R, Dasarathy S, Dasarathy J, Sargent R, Hawkins C, Pai RK, Yerian L, Khiyami A, Pagadala MR, Sourianarayanane A, Alkhouri N, McCullough AJ. The development of a non-invasive model to predict the presence of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:995–1000. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh GB, McCullough AJ. Natural History of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:1226–1233. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4095-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte P, Amarapurkar D, Agal S, Baijal R, Kulshrestha P, Pramanik S, Patel N, Madan A, Amarapurkar A, Hafeezunnisa Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:854–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque M, Sanyal AJ. The metabolic abnormalities associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:709–731. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnois F, Msika S, Sabate JM, Mechler C, Jouet P, Barge J, Coffin B. Prevalence and predictive factors of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in morbidly obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:183–188. doi: 10.1381/096089206775565122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyotylainen T, Jerby L, Petaja EM, Mattila I, Jantti S, Auvinen P, Gastaldelli A, Yki-Jarvinen H, Ruppin E, Oresic M. Genome-scale study reveals reduced metabolic adaptability in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Commun. 2016;7:8994. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin ES, Szuszkiewicz-Garcia M, Browning JD, Baxter JD, Abate N, Malloy CR. Influence of liver triglycerides on suppression of glucose production by insulin in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:235–243. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasumov T, Adams JE, Bian F, David F, Thomas KR, Jobbins KA, Minkler PE, Hoppel CL, Brunengraber H. Probing peroxisomal beta-oxidation and the labelling of acetyl-CoA proxies with [1-(13C)]octanoate and [3-(13C)]octanoate in the perfused rat liver. Biochem J. 2005;389:397–401. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasumov T, Dabkowski ER, Shekar KC, Li L, Ribeiro RF, Jr, Walsh K, Previs SF, Sadygov RG, Willard B, Stanley WC. Assessment of cardiac proteome dynamics with heavy water: slower protein synthesis rates in interfibrillar than subsarcolemmal mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1201–1214. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00933.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koliaki C, Szendroedi J, Kaul K, Jelenik T, Nowotny P, Jankowiak F, Herder C, Carstensen M, Krausch M, Knoefel WT, Schlensak M, Roden M. Adaptation of hepatic mitochondrial function in humans with non-alcoholic fatty liver is lost in steatohepatitis. Cell Metab. 2015;21:739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenblat KM, Fabbrini E, Mohammed BS, Klein S. Liver, muscle, and adipose tissue insulin action is directly related to intrahepatic triglyceride content in obese subjects. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1369–1375. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotronen A, Seppala-Lindroos A, Vehkavaara S, Bergholm R, Frayn KN, Fielding BA, Yki-Jarvinen H. Liver fat and lipid oxidation in humans. Liver Int. 2009;29:1439–1446. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JE, Ramos-Roman MA, Browning JD, Parks EJ. Increased de novo lipogenesis is a distinct characteristic of individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:726–735. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau BR, Wahren J, Chandramouli V, Schumann WC, Ekberg K, Kalhan SC. Use of 2H2O for estimating rates of gluconeogenesis. Application to the fasted state. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1995;95:172–178. doi: 10.1172/JCI117635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterburg BH, Adams JD, Mitchell JR. Hepatic glutathione homeostasis in the rat: efflux accounts for glutathione turnover. Hepatology. 1984;4:586–590. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JJ, Lambert JE, Hovhannisyan Y, Ramos-Roman MA, Trombold JR, Wagner DA, Parks EJ. Palmitoleic acid is elevated in fatty liver disease and reflects hepatic lipogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:34–43. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.092262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]