Abstract

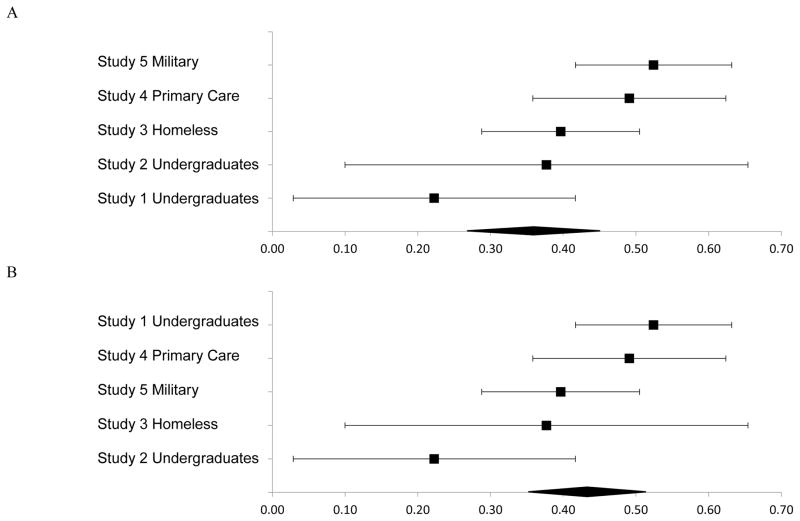

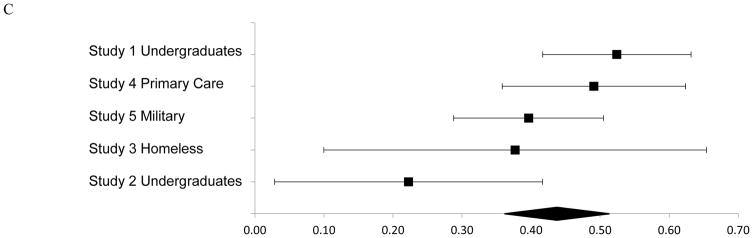

Perceived social problem-solving deficits are associated with suicide risk; however, little research has examined the mechanisms underlying this relationship. The interpersonal theory of suicide proposes two mechanisms in the pathogenesis of suicidal desire: intractable feelings of thwarted belongingness (TB) and perceived burdensomeness (PB). This study tested whether TB and PB serve as explanatory links in the relationship between perceived social problem-solving (SPS) deficits and suicide-related behaviors cross-sectionally and longitudinally. The specificity of TB and PB was evaluated by testing depression as a rival mediator. Self-report measures of perceived SPS deficits, TB, PB, suicidal ideation, and depression were administered in five adult samples: 336 and 105 undergraduates from two universities, 53 homeless individuals, 222 primary care patients, and 329 military members. Bias-corrected bootstrap mediation and meta-analyses were conducted to examine the magnitude of the direct and indirect effects, and the proposed mediation paths were tested using zero-inflated negative binomial regressions. TB and PB were significant parallel mediators of the relationship between perceived SPS deficits and ideation cross-sectionally, beyond depression. Longitudinally and beyond depression, in one study, both TB and PB emerged as significant explanatory factors, and in the other, only PB was a significant mediator. Findings supported the specificity of TB and PB: depression and SPS deficits were not significant mediators. The relationship between perceived SPS deficits and ideation was explained by interpersonal theory variables, particularly PB. Findings support a novel application of the interpersonal theory, and bolster a growing compendium of literature implicating perceived SPS deficits in suicide risk.

Keywords: problem solving, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, suicidal ideation, interpersonal theory of suicide

Suicide is a leading cause of death in the United States (U.S.; CDC, 2015) and it is estimated that suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts occur at even greater rates. For instance, in 2013, an estimated 9.3 million adults (3.9% of the U.S. population) thought about suicide, 1.3 million attempted suicide, and 41,149 died by suicide (CDC, 2015). In order to improve suicide prevention strategies and treatments, it is important to better understand modifiable factors that predict risk, and the mechanisms that may be driving their relationship with suicide risk.

Social problem-solving deficits, or difficulties identifying problems and generating appropriate solutions, is one of the most robust cognitive risk factors associated with suicide-related behaviors (c.f. cognitive rigidity; D’Zurilla & Nezu, 1982, 1990; Rudd, Rajab, & Dahm, 1994; Shneidman, 1957). Deficits in social problem-solving ability may be characterized by a negative problem orientation (viewing problems as threats, doubting problem-solving abilities, tendency to be frustrated when facing problems), an impulsive/careless style (attempting to solve problems hurriedly or not in a thorough manner), and/or an avoidant style (passivity, inaction, procrastination, overdependence on others). Indeed, social problem-solving deficits have been consistently identified as a suicide risk factor across various demographic groups (McAuliffe et al., 2006; McLaughlin, Miller, & Warwick, 1996; Pollock & Williams, 2004; Roskar, Bucik, & Valentin, 2007; Speckens & Hawton, 2005). For example, Pollock and Williams (2004) and Linehan and colleagues (1987) both found that suicide attempters demonstrated greater passivity in their problem-solving approach in comparison to non-suicidal psychiatric inpatients, consistent with an avoidant problem-solving style. In another study of suicide attempters’ problem-solving approach, higher rates of impulsivity and carelessness, and a tendency to adopt a negative outlook on problems were found (Ghahramanlou-Holloway, Bhar, Brown, Olsen, & Beck, 2012). Across twenty-two studies examining social problem-solving deficits among suicide attempters, ideators, and non-suicidal controls, social problem-solving deficits were consistently found in attempters, including the inability to generate multiple solutions and tendency to view problems as threats to well-being (Speckens & Hawton, 2005). Conversely, enhanced problem-solving abilities have been associated with decreased suicide risk (e.g., Hirsch, Chang, & Jeglic, 2012). Of particular import, treatments targeting problem-solving abilities have been demonstrated to decrease suicide risk among individuals with a history of suicide attempts (e.g., Cognitive Therapy, Ghahramanlou-Holloway et al., 2012; Problem-Solving Therapy, Stewart, Quinn, Plever, & Brett, 2009). Although converging evidence suggests that general social problem-solving deficits are important suicide-related correlates, little research has examined the mechanisms underlying their relationship.

Research investigating potential underlying mechanisms has implicated nonspecific autobiographical memory recall in the link between social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk (Evans, Williams, O’Loughlin, & Howells, 1992). However, findings are mixed, with some studies failing to find support for memory deficits as the explanatory factor (Kremers, Spinhoven, Van der Does, & Van Dyck, 2006). Others have proposed that depressive symptoms explain this association (Reinecke et al., 2001); however, here too, findings have been inconclusive. Some studies have reported null mediation findings (e.g., Harrington et al., 2000), and one review noted that most studies only entered depression as a covariate and did not test for mediation (Speckens & Hawton, 2005). Thus, the mechanisms underlying the relationship between social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk have yet to be fully established.

One theory that may illuminate the link between these variables is the interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Building on early theories of social needs (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), the interpersonal theory proposes that individuals desire suicide when they simultaneously experience intractable feelings of perceived burdensomeness (i.e., belief that one’s life places a burden on family, friends, and/or society) and thwarted belongingness (i.e., feeling that one is disconnected from others). Further, this theory proposes that those who die by suicide not only desire suicide, but also possess the capability for suicide (i.e., increased pain tolerance and fearlessness about death). Core predictions of the interpersonal theory have been supported across a variety of populations (Christensen, Batterham, Soubelet, & Mackinnon, 2012; Chu et al., under review; Cukrowicz, Jahn, Graham, Poindexter, & William, 2013; Hagan, Podlogar, Chu, & Joiner, 2015; Silva et al., 2016; Stanley, Hom, Rogers, Hagan, & Joiner, 2016). Although a systematic review that did not include a meta-analytic component found that some theory predictions have remained heretofore untested (e.g., the role of hopelessness about the tractability of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness; Ma, Batterham, Calear, & Han, 2016), a more recent meta-analysis conducted by Chu and colleagues (under review) found support for the interpersonal theory propositions, albeit effect sizes were small. Indeed, both Ma et al. (2016) and Chu et al. (under review) suggest that more research on the theory is needed—a call to which the present study responds. Given that the interpersonal theory posits that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are proximal predictors of suicidal desire, it is possible that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness explain the relationship between social problem-solving deficits, a distal suicide risk factor, and suicide risk.

Although no studies have directly examined the relationship between social problem-solving deficits and thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, researchers have long established the importance of successful interpersonal functioning in psychological well-being (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 2012). Indeed, there has been research linking greater levels of social problem-solving ability with successful interpersonal functioning. This is not surprising as those who are able to adaptively cope with interpersonal challenges may also have greater social confidence and skills, and consequently, develop and maintain a stronger social support network (D’Zurilla & Nezu, 2010; D’Zurilla, Nezu, & Maydeu-Olivares, 2002; Lui, Lee, Greenwood, & Ross, 2012). These individuals may be more likely to rely on their social network in times of distress, which may mitigate feelings of thwarted belongingness and further ameliorate suicide risk. Those who do not actively pursue solutions may not engage social support networks appropriately or fear being rebuffed (Chao, 2011; Friedman, 2006; Jakupcak et al., 2014), which could contribute to an increased sense of isolation from others.

Further, effective interpersonal functioning and stronger bonds with others may increase feelings that one is valued, an integral part of society, and not a burden on others. Indeed, research on social role valorization highlights the negative impact of being devalued by society, including being cast into a negative social role and as a burden on society (Wolfensberger, 2000). Additionally, researchers have found that the ability to solve problems and manage daily stressors may result in increased feelings of self-efficacy and a reduced perception of being a burden on others (Marks, Allegrante, & Lorig, 2005; Robinson-Smith, Johnston, & Allen, 2000). As noted above, those who do not pursue solutions may fear negative social consequences, such as criticisms from others, which may contribute to increased perceptions of burdensomeness on others. These findings suggest that the ability to problem solve effectively may diminish perceived burdensomeness and, in turn, suicide risk.

Altogether, results suggest that conversely, individuals with perceived deficits in social problem-solving ability (i.e., passivity and impulsivity, a negative mindset when facing problems) may be less interpersonally effective, which could lead to greater interpersonal conflict, decreased social connection, and increased feelings of thwarted belongingness. Additionally, an ineffective problem-solving approach may diminish feelings of self-efficacy and social value, thereby increasing feelings of perceived burdensomeness.

Present Study

Although social problem-solving deficits have been linked to interpersonal difficulties and suicide risk, there is a paucity of information on how thwarted interpersonal needs may explain these associations from the perspective of the interpersonal theory. This manuscript addresses this gap in the literature by examining the mediating roles of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicidal ideation in five different samples. As research has indicated that perceived burdensomeness may be a more robust predictor of suicidal ideation than thwarted belongingness cross-sectionally (e.g., Bryan et al., 2010; Chu et al., 2016a) and prospectively (Chu et al., 2016c), we tested perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness as both parallel and individual mediators of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and ideation. We hypothesized that perceived problem-solving deficits would be positively associated with thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal ideation, and thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would mediate the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and ideation. Specifically, perceived social problem-solving deficits would emerge as a distal suicide risk factor and the interpersonal theory variables would be proximal risk factors (Figure 1).

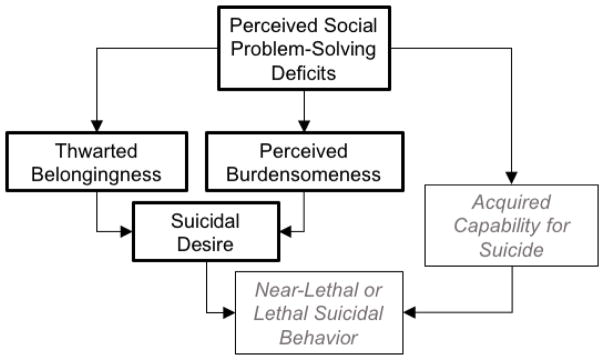

Figure 1.

Hypothesized explanatory model for the association between perceived social problem-solving deficits and near-lethal or lethal suicidal behavior from the perspective of the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide (Joiner, 2005). Constructs denoted in gray were not specifically evaluated in this study.

To strengthen findings, we evaluated the specificity of the two proposed mediators. First, we examined whether perceived social problem-solving deficits (independent variable) and thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (mediators) were interchangeable in their roles. We predicted that perceived social problem-solving deficits would not mediate the relationship between the interpersonal theory variables and ideation. Next, we tested an alternative explanatory mechanism—depressive symptoms—that has been linked to both social problem-solving deficits and suicidal symptoms (Speckens & Hawton, 2005). We postulated that depressive symptoms would not account for their relationship, which supports the robustness of our two proposed mediators. Additionally, in Studies 1, 2, and 5 where the suicide-related dependent variable demonstrated excess zeroes, we examined the proposed mediation pathways using zero inflated negative binomial regressions; we expected that the pattern of findings would remain the same even after accounting for excess zeroes. Finally, we conducted meta-analyses to examine the strength of the direct and indirect relationships between these variables across the five studies. For brevity and clarity, in all study methods and results, we refer to thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as TB and PB, respectively.

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at East Tennessee State University approved the study procedures for Study 1 (“ETSU PEAKS: Local Baseline Evaluation,” protocol #: c0210.26e-ETSU), Study 3 (“Characterization of Rural, Middle, and Older Adult Primary Care Patients with Chronic Medical Problems,” protocol #: 08-222s), and Study 4 (“Characterization of Rural, Middle, and Older Adult Primary Care Patients with Chronic Medical Problems,” protocol #: 08-222s). Study 2 was approved by the IRB at Florida State University (“Memory Perspective & Mental Rehearsal: Role of Cognitions in Suicidal Behavior,” protocol #: 2013.10048). Study 5 was approved by the IRB of Texas A&M University (IRB title and protocol # not available) and the USAMRMC (Human Research Protection Office).

Study 1: Undergraduate Students

First, we examined the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicidal symptoms through the pathways of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in an undergraduate student sample. We predicted that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would significantly account for the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk.1

Study 1 Method

Participants

Participants were 336 undergraduates attending a large university located in the Southeastern U.S. (participant details in Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Information for All Studies (N, %).

| Variables | Study 1 (N=336) | Study 2 (N=105) | Study 3 (N=53) | Study 4 (N=222) | Study 5 (N=329) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undergraduates | Undergraduates | Homeless Individuals | Primary Care Patients | Service Members | |

| Age Mean (SD) | 21.8 (5.3) years | 19.3 (2.5) years | 49.0 (11.6) years | 44.1 (12.4) years | 22.2 (2.8) years |

| Age Range | 17–58 years | 18–35 years | 23–69 years | 19–79 years | 18–37 years |

| Female | 225, 66.6% | 70, 65.4% | 16, 30.2% | 137, 61.7% | 56, 17.0% |

|

| |||||

| Ethnicity and Race | |||||

|

| |||||

| Hispanic/Latino | 6, 1.8% | 82, 76.6% | 2, 3.8% | 7, 3.2% | 35, 10.6% |

| Caucasian/White | 294, 87.5% | 86, 80.4% | 39, 73.6% | 193, 86.9% | 200, 60.8% |

| African American/Black | 18, 5.41% | 8, 7.5% | 8, 15.1% | 16, 7.2% | 84, 25.5% |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 10, 3.0% | 6, 5.6% | 0, 0% | 1, 0.5% | 5, 1.5% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | n/a | 1, 0.9% | 3, 5.7% | 2, 0.9% | 4, 1.2% |

| Other | n/a | 3, 2.9% | n/a | n/a | 1, 0.3% |

| Missing | 8, 2.4% | 1, 0.9% | 1, 1.9% | 3, 1.4% | n/a |

|

| |||||

| Suicidal Symptom History | |||||

|

| |||||

| Lifetime Suicidal Ideation | 50, 14.8% | 14, 13.1% | 11, 20.8% | 123, 55.4% | 132, 40.1% |

| No History of Suicide Attempts | 304, 90.5% | 88, 83.8% | 44, 83.0% | 181, 81.5% | 162, 49.2% |

| Lifetime Suicide Attempt | 22, 6.6% | 17, 15.9% | 9, 17.0% | 41, 18.5% | 167, 50.8% |

| 1 Previous Attempt | 11, 3.3% | 10, 9.5% | n/a | n/a | 103, 31.3% |

| 2+ Previous Attempts | 11, 3.3% | 7, 6.7% | n/a | n/a | 64, 19.5% |

| Missing | 10, 3.0% | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Note. N/A = data were not available.

Procedure

All participants provided electronic informed consent prior to initiating study procedures, which involved completing an online battery of questionnaires, and were compensated with course credit. Participants received a debriefing form that included mental health resources. Study 1 data have been previously used to investigate the relationship between suicide risk and traumatic events (Chang & Hirsch, 2015; Chang et al., 2017a; 2017b; 2015c), and risk factors for depression (Chang et al., 2015a; 2015b; Muyan et al., 2015).

Measures

Suicide Risk

The Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised (SBQ-R; Osman et al., 2001) is a 4-item measure of suicidal behaviors including lifetime history of ideation and future likelihood of suicidal behavior. Each question is scored on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 7. Items were summed for a total score and higher scores indicated higher frequency or severity of risk. Total scores ranged from 3 to 18; however, for zero inflated models, the suicide risk total score was adjusted by subtracting 3 points from all scores in order to obtain a low-end zero score. This measure has demonstrated good internal consistency across samples, including college undergraduates and adult psychiatric inpatients (0.76–0.88), and adequate discriminant validity when discriminating suicidal versus non-suicidal inpatients (standardized estimate=0.79; Osman et al., 2001). In this study, internal consistency was good (α=0.81).

Perceived social problem-solving ability

The Social Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised-Short Form (SPSI-R-SF; D’Zurilla et al., 2002) was used to assess perceived social problem-solving deficits. This 25-item questionnaire is scored using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 4. The SPSI-R-SF assesses two constructive or adaptive social problem-solving dimensions and three dysfunctional dimensions, yielding a total score and five subscales scores (positive problem orientation, rational problem solving, negative problem orientation, impulsive/careless style, and avoidant style; D’Zurilla et al., 2002). Low scores on positive dimensions and high scores on negative dimensions indicate greater deficits in social problem-solving ability. The five-factor structure of the SPSI-R-SF has been validated (CFI=0.91; D’Zurilla et al., 2002; Maydeu-Olivares & D’Zurilla, 1997). Across collegiate, clinical, and community samples (D’Zurilla et al., 2002; Hawkins, Sofronoff, & Sheffield, 2009; Morera et al., 2006; Nezu, Nezu, & Perri, 1989; Spence, Sheffield, & Donovan, 2002), the SPSI-R-SF has demonstrated good internal consistency (α=0.73–0.79), and test-retest reliability over three weeks (r=0.91). Given the focus of this study on general problem-solving deficits as distal suicide risk factors, we used the SPSI-R-SF total score, which was calculated by reverse-scoring the positive items and summing all negative and reverse-scored positive items. Thus, higher total scores are indicative of greater perceived social problem-solving deficits. Internal consistency was excellent (α=0.92).

Thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-18 (INQ-18; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012) was used to assess TB and PB. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7 (Van Orden et al., 2012). The 9-item TB subscale (INQ-TB) measures the extent to which the individual feels connected to other people, and the 9-item PB subscale (INQ-PB) assesses perceptions that one is a burden on others. Each subscale score ranges from 9 to 63. Where indicated, items were reverse scored; higher scores indicate greater severity. In this study, the PB and TB scales both exhibited excellent internal consistency (both αs=0.92).

Rival mediator

A comprehensive measure of depression symptoms was not available in this sample (a point that we discuss below and remedy in Study 2); however, the National College Health Association Measure (NCHA, Original Version; American College Health Association, 2009) is a 123-item measure of physical and mental health-related activities and behaviors, and each item was designed to be used individually. In this study, one item assessing depressive symptoms (i.e., impacting academic functioning) in the preceding year was used.

Statistical analyses

First, variables of interested were evaluated descriptively and Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were generated to examine between-variable associations. Prior to conducting primary analyses, data across all samples were screened for outliers and violations of normality. In Study 1, two variables evidenced potentially problematic levels of skew and kurtosis (SBQ-R total, INQ-TB); therefore, robust Maximum Likelihood (MLR) was selected as the estimation method for our analyses. Full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) maximizes the likelihood of the model given the data and assumes multivariate normality. Thus, FIML was used to handle missing data. When data are non-normal, FIML can be used (with MLR) to obtain standard errors and test statistics robust to non-normality (Brown, 2006).

Structural equation analyses using MPlus 7 were used to the test the following models: (A) TB and PB (INQ) as parallel mediators of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits (SPSI-SF-R) and suicide risk (SBQ-R), controlling for depressive symptoms; (B) TB as an individual mediator of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk, controlling for depressive symptoms; (C) PB as an individual mediator of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk, controlling for depressive symptoms; (D) perceived social problem-solving deficits as the mediator of the association between TB and PB and suicidal ideation, controlling for depressive symptoms; and (E) depressive symptoms as the mediator of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk, controlling for TB and PB. Previous research has shown age and sex differences in suicide risk (Beautrais, 2001; Van Orden et al., 2010); therefore, age and sex were covaried in all models.

In all five mediation models, 10,000 bootstrapped samples were drawn from the data, and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals were used to estimate the indirect effects of each of the resampled datasets. This statistical approach estimates path coefficients and generates bootstrapped confidence intervals for total and specific indirect effects of X on Y through one or more mediator variable(s) M, while adjusting all paths for the potential influence of covariates not proposed as mediators in the model. If a true zero falls between the upper and lower confidence intervals, there is no significant indirect effect of the mediators.

In line with recommendations from Brown (2006) and Hu and Bentler (1999), several indices were used to evaluate model fit. The chi-square statistic (χ2) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), were used as indices of absolute fit, with non-significance of χ2 indicating perfect fit and SRMR values less than 0.10 indicating adequate fit and less than 0.08 indicating good fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is a parsimony-corrected fit statistic and RMSEA values less than 0.05 are interpreted as good fit and values between 0.06 and 0.08 indicate adequate fit. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) were used as indices of comparative fit, with CFI and TLI values between .90 and .95 indicating adequate model fit.

Finally, given prior research highlighting the need for tests of zero inflation in suicide-related research in non-clinical samples (Cukrowicz et al., 2013), we examined our suicide-related outcome variables for excess zeroes. Inspection of the histogram for our outcome variable, suicide risk, indicated relatively large numbers of zero-value responses as a proportion of the total Study 1 sample size (SBQ-R = 197/336). Thus, consistent with Cukrowciz et al. (2013), zero-inflated models were employed as these models allow for simultaneous estimation of both the zero and positive responses in the data (Greene, 2012). Due to the combination of overdispersion and excess zeros in the data, ZINB regressions were conducted using Stata 13 to confirm the α, β, c, and c’ pathways of our proposed mediator models (see Figure 2). Vuong’s test (Vuong, 1989) was employed to verify the utility of the ZINB model by evaluating the ZINB regression against the standard negative binomial regression (Atkins & Gallop, 2007); statistical significance of Vuong’s test supports the ZINB model.

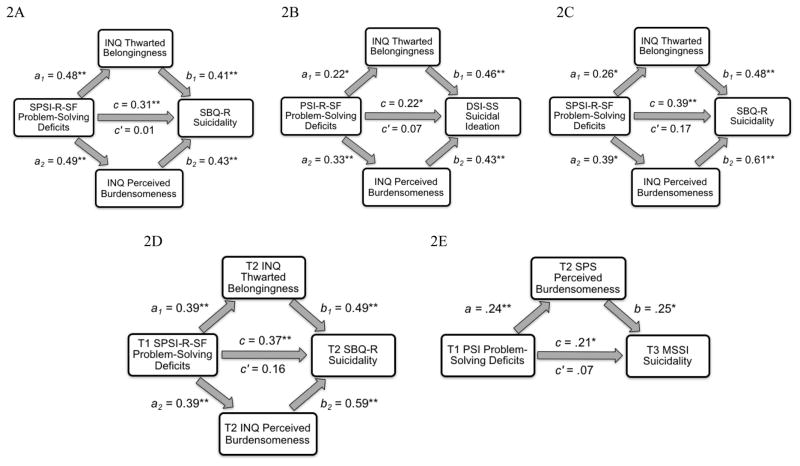

Figure 2.

Standardized regression coefficients for the cross-sectional relationship between deficits in problem-solving ability and suicidal ideation as mediated by thwarted interpersonal needs in Study 1 (2A), Study 2 (2B), Study 3 (2C), Study 4 (2D; T1 = Time 1, baseline. T2 = Time 2, 6–12 months after baseline), and Study 5 (2E; T1 = Time 1, baseline. T2 = Time 2, 1 month after baseline. T3 = Time 3, 6 months after baseline).

Note. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001. SPSI = Social Problem-Solving Inventory. INQ = Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. SBQ-R = Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire-Revised. PSI-R-SF = Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised-Short Form. DSI-SS = Depressive Symptom Inventory – Suicidality Subscale. SBQ-R = Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire-Revised.

Power

With regard to power, previous research has indicated that a sample size of 53 is required to be adequately powered (0.80) to detect moderate effect sizes for the α path and large effect sizes for the β path using a bias-corrected bootstrap mediation approach (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). Thus, with our sample size of 336, we were adequately powered for mediation analyses. Additionally, based on Monte Carlo simulations (Wolf, Harrington, Clark, & Miller, 2013), there was sufficient power to evaluate model fit indices in Study 1.

Study 1 Results

Preliminary Analyses

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between all Study 1 variables are in Table 2. As hypothesized, deficits in perceived social problem-solving deficits were significantly and positively related to TB, PB, and suicide risk (r=0.32–0.49, ps<0.001).

Table 2.

All Study Variable Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations.

| Study 1 – Undergraduates | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | -- | -- | N | Mean | SD | Range | Skew |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. INQ-18 Thwarted Belongingness | -- | 334 | 24.34 | 11.80 | 9–57 | 0.41 | |||||

| 2. INQ-18 Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.781** | -- | 334 | 20.24 | 10.95 | 9–61 | 0.90 | ||||

| 3. SBQ-R Suicide Risk | 0.406** | 0.433** | -- | 336 | 4.74 | 2.73 | 3–14 | 1.58 | |||

| 4. SPSI-R Social Problem-Solving Deficits | 0.481** | 0.488** | 0.319** | -- | 334 | 31.13 | 13.30 | 4–78 | 0.37 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Study 2 – Undergraduates | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | -- | -- | N | Mean | SD | Range | Skew |

|

| |||||||||||

| 1. INQ-15 Thwarted Belongingness | -- | 105 | 21.37 | 11.21 | 9–59 | 1.19 | |||||

| 2. INQ-15 Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.467** | -- | 105 | 8.41 | 4.69 | 6–32 | 1.45 | ||||

| 3. DSI-SS Suicidal Ideation | 0.457** | 0.431** | -- | 105 | 0.39 | 1.03 | 0–5 | 2.21 | |||

| 4. PSI-R-SF Social Problem-Solving Deficits | 0.219* | 0.330** | 0.221* | -- | 105 | 41.74 | 12.31 | 16–84 | 0.97 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Study 3 – Homeless Individuals | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | -- | -- | N | Mean | SD | Range | Skew |

|

| |||||||||||

| 1. INQ-15 Thwarted Belongingness | -- | 53 | 36.09 | 13.40 | 9–63 | −0.18 | |||||

| 2. INQ-15 Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.539** | -- | 53 | 15.98 | 9.97 | 5–42 | 0.90 | ||||

| 3. SBQ-R Suicide Risk | 0.476** | 0.612** | -- | 53 | 7.32 | 4.00 | 3–16 | 0.65 | |||

| 4. SPSI-R Social Problem-Solving Deficits | 0.360* | 0.391* | 0.391* | -- | 53 | 37.36 | 17.43 | 4–80 | 0.12 | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| Study 4 – Primary Care Patients | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | N | Mean | SD | Range | Skew |

|

| |||||||||||

| 1. T1 INQ-15 Thwarted Belongingness | -- | 216 | 31.24 | 14.00 | 9–63 | 0.06 | |||||

| 2. T1 INQ-15 Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.634** | -- | 222 | 15.86 | 10.67 | 6–42 | 0.91 | ||||

| 3. T1 SBQ-R Suicide Risk | 0.519** | 0.614** | -- | 217 | 6.25 | 3.66 | 3–18 | 1.01 | |||

| 4. T2 INQ-15 Thwarted Belongingness | 0.525** | 0.480** | 0.472** | -- | 98 | 27.17 | 13.44 | 9–57 | 0.43 | ||

| 5. T2 INQ-15 Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.411** | 0.593** | 0.480** | 0.701** | -- | 99 | 14.15 | 10.39 | 6–42 | 1.28 | |

| 6. T2 SBQ-R Suicide Risk | 0.465** | 0.556** | 0.755** | 0.487** | 0.586** | -- | 99 | 5.98 | 3.61 | 3–18 | 1.22 |

| 7. T1 SPSI-R Social Problem-Solving Deficits | 0.455** | 0.479** | 0.381** | 0.392** | 0.392** | 0.365** | 221 | 34.90 | 18.39 | 1–96 | 0.66 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Study 5 – Military Service Members | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | N | Mean | SD | Range | Skew |

|

| |||||||||||

| 1. T1 SPS Thwarted Belongingness | -- | 329 | 11.72 | 4.50 | 3–21 | −0.04 | |||||

| 2. T1 SPS Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.711** | -- | 329 | 8.44 | 3.48 | 4–16 | 0.33 | ||||

| 3. T1 MSSI Suicidal Ideation | 0.423** | 0.521** | -- | 329 | 23.39 | 10.32 | 0–51 | −0.22 | |||

| 4. T2 SPS Thwarted Belongingness | 0.427** | 0.325** | 0.282** | -- | 251 | 9.35 | 4.06 | 3–21 | 0.40 | ||

| 5. T2 SPS Perceived Burdensomeness | 0.255** | 0.399** | 0.313** | 0.652** | -- | 251 | 6.80 | 2.82 | 3–16 | 0.95 | |

| 6. T3 MSSI Suicidal Ideation | 0.156* | 0.173* | 0.239** | 0.262** | 0.245* | -- | 139 | 3.78 | 8.37 | 0–40 | 1.29 |

| 7. T1 PSI Social Problem-Solving Deficits | 0.377** | 0.471** | 0.369** | 0.198* | 0.237** | 0.214* | 308 | 108.32 | 25.39 | 35–175 | −0.15 |

Note.

p < 0.05;

p ≤ 0.001.

INQ = Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. SBQ-R = Suicidal Behavior Questionnaire – Revised. DSI-SS = Depressive Symptom Inventory- Suicidality Subscale. PSI-R-SF = Problem Solving Inventory-Revised-Short-Form. SPSI-R = Social Problem Solving Inventory-Revised. SPS = Suicide Probability Scale. MSSI = Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation. PSI = Problem Solving Inventory. Study 4: T1 = Time 1. T2 = Time 2, 6 months after T1. Study 5: T2 = Time 2, 1 month after T1. T3 = Time 3, 6 months after T1.

TB and PB as Parallel Mediators

We examined TB and PB as parallel mediators of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk, controlling for age and sex. This model demonstrated excellent model fit (χ2(1) = 0.005, p = 0.94; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.01 (0.01, 0.03), CFI/TLI = 0.99, 0.96; SRMR = 0.01). All α and β pathways in the mediation model were significant. The direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for TB and PB, indicating mediation. The indirect effect of TB and PB on the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk, controlling for age and sex, was estimated to be between 0.0287 and 0.0648, indicating significance as the 95% confidence interval did not cross zero. The pattern of findings remained the same after controlling for depressive symptoms with the overall regression model explaining a significant amount of variance in suicide risk (R2=0.26, b=0.040, SE=0.01, 95%CI=0.0244, 0.0567; Figure 2A; see Table 3 for details).

Table 3.

Summary of the Main Results for Models in All Studies.

| Study 1 – Undergraduates | SPS->TB | TB->SI | SPS->PB | PB->SI | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A: Main | R2=0.26, F[6,318]=18.61*** | b=0.42***, SE=0.04 | b=0.03*, SE=0.02 | b=0.40***, SE=0.04 | b=0.07**, SE=0.02 | b=0.03, SE=0.01 | b=0.042, SE=0.008 | 0.0256, 0.0586 |

| B: TB | R2=0.24, F[5,319]=19.75*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.040**, SE=0.01 | b=0.032, SE=0.008 | 0.0183, 0.0478 |

| C: PB | R2=0.26, F[5,319]=21.94*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.040**, SE=0.01 | b=0.038, SE=0.01 | 0.0231, 0.0555 |

|

| ||||||||

| Study 2 – Undergraduates | SPS->TB | TB->SI | SPS->PB | PB->SI | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | 95%CI | |

|

| ||||||||

| A: Main | R2=0.44, F[6,98]=12.96*** | b=0.25**, SE=0.09 | b=0.02***, SE=0.005 | b=0.13**, SE=0.04 | b=0.03**, SE=0.01 | b=0.002, SE=0.004 | b=0.026, SE=0.02 | 0.0021, 0.0073 |

| B: TB | R2=0.43, F[5,99]=14.78*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.003, SE=0.004 | b=0.006, SE=0.003 | 0.0018, 0.0125 |

| C: PB | R2=0.44, F[5,99]=15.38*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.002, SE=0.004 | b=0.007, SE=0.003 | 0.0023, 0.0159 |

|

| ||||||||

| Study 3 – Homeless Individuals | SPS->TB | TB->SI | SPS->PB | PB->SI | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | 95%CI | |

|

| ||||||||

| A: Main | R2=0.54, F[6,46]=8.88*** | b=0.20**, SE=0.11 | b=0.06**, SE=0.04 | b=0.21**, SE=0.08 | b=0.16**, SE=0.06 | b=0.04, SE=0.03 | b=0.046, SE=0.03 | 0.0015, 0.1017 |

| B: TB | R2=0.50, F[5,47]=9.54*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.058*, SE=0.03 | b=0.0237, SE=0.02 | −0.0169, 0.0151 |

| C: PB | R2=0.53, F[5,47]=10.55*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.0387, SE=0.0275 | b=0.0433, SE=0.02 | 0.0070, 0.0936 |

|

| ||||||||

| Study 4 – Primary Care Patients | SPS->TB | TB->SI | SPS->PB | PB->SI | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | 95%CI | |

|

| ||||||||

| A: Main | R2=0.44, F[6,182]=27.79*** | b=0.34***, SE=0.05 | b = 0.06**, SE=0.02 | b=0.25***, SE=0.04 | b=0.16***, SE=0.03 | b=0.004, SE=0.01 | b=0.0224, SE=0.0084 | 0.0093, 0.0431 |

| B: TB | R2=0.35, F[5,183]=19.99*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.0177, SE=0.01 | b=0.0084, SE=0.005 | 0.0110, 0.0204 |

| C: PB | R2=0.43, F[5,188]=27.98*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.0079, SE=0.01 | b=0.0189, SE=0.01 | 0.0068, 0.0374 |

| D: Main | R2=0.33, F[6,80]=6.61*** | b=0.28***, SE=0.07 | b=0.03**, SE=0.03 | b=0.22***, SE=0.05 | b=0.15***, SE=0.04 | b=0.001, SE=0.02 | b=0.0324, SE=0.01 | 0.0111, 0.0720 |

| E: TB | R2=0.25, F[5,81]=5.34*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.0223, SE=0.02 | b=0.0113, SE=0.0087 | 0.0003, 0.0391 |

| F: PB | R2=0.33, F[5,83]=8.07*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.0044, SE=0.02 | b=0.0298, SE=0.01 | 0.0088, 0.0629 |

|

| ||||||||

| Study 5 – Military Service Members | SPS->TB | TB->SI | SPS->PB | PB->SI | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | 95%CI | |

|

| ||||||||

| A: Main | R2=0.36, F[6,225]=20.63*** | b=0.07***, SE=0.01 | b=0.19*, SE=0.04 | b=0.06***, SE=0.01 | b=1.22***, SE=0.20 | b=0.05, SE=0.03 | b=0.0928, SE=0.02 | 0.0676, 0.1348 |

| B: TB | R2=0.26, F[5,226]=15.75*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.0986**, SE=0.03 | b=0.0532, SE=0.01 | 0.0300, 0.0835 |

| C: PB | R2=0.35, F[5,227]=24.75*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.0525*, SE=0.03 | b=0.0971, SE=0.02 | 0.0678, 0.1335 |

| D: Main | R2=0.10, F[7,111]=1.82 | b=0.04**, SE=0.01 | b=−0.06, SE = 0.23 | b=0.02*, SE=0.01 | b=0.80*, SE=0.36 | b=0.0163, SE=0.03 | b=0.009, SE=0.01 | −0.0074, 0.0496 |

| E: TB | R2=0.06, F[6,112]=1.17 | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.0201, SE=0.04 | b=0.0047, SE=0.01 | −0.0035, 0.0319 |

| F: PB | R2=0.10, F[6,113]=3.34* | -- | -- | -- | -- | b=0.016, SE=0.03 | b=0.0175, SE=0.01 | 0.0047, 0.0425 |

Note.

p < 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001.

SPS = perceived social problem-solving deficits. TB = thwarted belongingness. PB = perceived burdensomeness. SI = suicidal ideation.

A) Cross-Sectional Main Test: TB and PB as parallel mediators of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving ability (IV) and suicidal ideation (DV), controlling for depression, age and sex. For Study 5, results from Time 1 are presented.

B) Cross-Sectional TB Individually: TB as the mediator of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving ability (IV) and suicidal ideation (DV), controlling for depression, age and sex. For Study 5, results from Time 1 are presented.

C) Cross-Sectional PB Individually: PB as the mediator of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving ability (IV) and suicidal ideation (DV), controlling for depression, age and sex. For Study 5, results from Time 1 are presented.

D) Longitudinal Main Test: see A). Study 4 (SPS Time 1 -> TB/PB Time 2 -> SI Time 2); Study 5 (SPS Time 1 -> TB/PB Time 2 -> SI Time 3).

E) Longitudinal TB Individually: see B). Study 4 (SPS Time 1 -> TB Time 2 -> SI Time 2); Study 5 (SPS Time 1 -> TB Time 2 -> SI Time 3).

F) Longitudinal PB Individually: see C). Study 4 (SPS Time 1 -> PB Time 2 -> SI Time 2); Study 5 (SPS Time 1 -> PB Time 2 -> SI Time 3).

ZINB regression model results were consistent with hypotheses. TB (estimate = 0.049, SE = 0.009, p < 0.001, Wald χ2 = 35.60) and PB (estimate = 0.053, SE = 0.008, p < 0.001, Wald χ2 = 34.33), individually, were both significantly associated with suicide risk. The model with social problem solving deficits as a predictor of suicide risk, controlling for age and sex, was significant, with Wald χ2 equal to 18.54, p < 0.001. Social problem-solving deficits were significantly associated with suicide risk (estimate = 0.033, robust SE = 0.008, p < 0.001). When TB and PB were included into the model, the Wald χ2 value was significant (16.10, p < 0.001). However, the main effect of social problem solving deficits on suicide risk was no longer significant (estimate = 0.015, SE = 0.008, p = 0.08). While the ZINB results are consistent with our proposed pathways, Vuong’s test (Vuong, 1989) was not significant (p < 0.001), which supports the ZINB models.

Specificity of TB and PB as Mediators

Mediation analyses reversing the variables in the α path indicated that the effect of TB (β=−0.001; 95%CI=−0.003, 0.001) and PB (β=−0.001; 95%CI=−0.0029, 0.001) on suicide risk was not significantly mediated by perceived social problem-solving deficits, which supports the specificity of the roles of the independent variable (social problem-solving deficits) and the mediators (TB, PB). Depressive symptoms did not mediate the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk, controlling for TB, PB, age and sex (b=−0.004, SE=0.060; 95%CI=−0.029, 0.008).

TB and PB as Individual Mediators

When TB was tested as an individual mediator, the direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk remained significant after accounting for TB and the indirect effect of TB was significant, estimated to be between 0.0183 and 0.0478 (R2=0.0807, κ2=0.1479). The overall model was significant (R2=0.24) and the goodness-of-fit ranged from poor to excellent (χ2(1) = 1.43, p = 0.33; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.06 (0.04, 0.09), CFI/TLI = 0.81, 0.77; SRMR = 0.07). A similar pattern emerged for PB: the direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk remained significant after accounting for PB and the indirect effect of PB was significant, estimated to be between 0.0231 and 0.0555 (R2=0.0850, κ2=0.1639). For PB as an individual mediator, the overall model was significant (R2=0.26) and goodness-of-fit ranged from good to excellent (χ2(1) = 1.05, p = 0.10; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.05 (0.03, 0.06), CFI/TLI = 0.89, 0.90; SRMR = 0.06).

Study 1 Discussion

Study 1 tested our hypotheses in an undergraduate student sample. Our hypotheses were supported—consistent with previous research (McAuliffe et al., 2006; McLaughlin, Miller, & Warwick, 1996), greater perceived social problem-solving deficits were associated with higher levels of thwarted interpersonal needs and, in turn, more severe suicide risk. Our findings were consistent with the interpersonal theory and showed that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness were significant explanatory links. In line with these findings, the model including both thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as mediators exhibited excellent fit. Individually, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness only partially mediated the association between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk.

Consistent with prior research suggesting that perceived burdensomeness may be a stronger predictor than thwarted belongingness (e.g., Bryan et al., 2010), our findings indicated that the individual mediator model with perceived burdensomeness accounted for a similar amount of variance in suicide as the model with both mediators. Additionally, the two models with perceived burdensomeness demonstrated good to excellent fit, while the individual mediator model with thwarted belongingness exhibited poorer fit indices. These findings may indicate that the inclusion of thwarted belongingness does not significantly improve our ability to predict variance in suicide risk or that perceived burdensomeness is a more robust predictor of risk.

Of note, this pattern of results remained significant even after accounting for depression, sex and age. Prior research has demonstrated that depressive symptoms are not only robustly linked to suicide risk (Ellis & Rutherford, 2008), but also to social problem-solving deficits (Speckens & Hawton, 2005). Therefore, that our findings remained significant even after controlling for depression highlights the robustness of the interpersonal theory variables. Additionally, analyses with depression as the mediator indicated that depression did not mediate the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk, controlling for thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Further, the proposed pathways in our mediation models were supported when analyses were conducted to account for an excess of zeroes in our suicide risk outcome variable. These findings, altogether, further bolster the specificity and robustness of our proposed hypotheses.

Study 1 had four primary limitations. First, the sample was undergraduate students who are generally high functioning; thus, results may not generalize to clinical populations. Second, by virtue of their student status, it could be that individuals in Study 1 had higher baseline levels of perceived social problem-solving deficits (e.g., navigating the social sphere of a university, including courses and living with peers). Third, data for Study 1 were cross-sectional, limiting our ability to establish temporality in the meditational pathways, although it is emphasized that reversing the independent and mediator variables did not produce a significant model. Finally, in this sample, only one item was used to measure depressive symptoms and the use of more robust measures of depression would strengthen these results. Given that this is the first study, to our knowledge, to examine this hypothesis in an undergraduate sample, replication is needed.

Study 2: Undergraduate Students

In Study 2, we sought to replicate Study 1 in a different sample of undergraduate students. As in Study 1, we hypothesized that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would, again, emerge as significant explanatory factors.

Study 2 Method

Participants

Participants were 105 students recruited from the undergraduate psychology subject pool at a large, public university located in the Southern U.S. (details in Table 1). Notably, data for Studies 1 and 2 were collected from different universities.

Procedure

Respondents provided informed consent, filled out a series of self-report questionnaires, and were provided with mental health resources during debriefing. Data for Study 2 were obtained as part of a larger study on autobiographical recall and suicidal ideation (see Chu et al., 2015a for details). These data have previously been used to examine the relationship between suicide risk and fear of negative evaluation (Chu et al., 2015b) and psychopathy (Brislin, Buchman-Schmitt, Patrick, & Joiner, 2016; Buchman-Schmitt et al., 2016).

Measures

Suicidal ideation

The Depressive Symptom Inventory-Suicidality Subscale (DSI-SS; Metalsky & Joiner, 1997), a 4-item self-report measure, was used to assess the frequency and intensity of suicidal thoughts in the previous two weeks. Scores range from 0 to 3 with higher scores reflect an increased severity of suicidal ideation. Prior studies have reported good validity and psychometric properties (Joiner, Pfaff, & Acres, 2002). Both the DSI-SS and SBQ-R, which was utilized in Study 1, have been identified to have particularly strong psychometric properties relative to other self-report measures of suicide risk (Batterham et al., 2015). In this study, the internal consistency of the DSI-SS was good (α=0.80).

Perceived social problem-solving ability

The Problem-Solving Inventory-Revised-Short Form (PSI-R-SF; Maydeu-Olivares & D’Zurilla, 1997) is a 16-item, 6-point Likert-type self-report measure of perceived social problem-solving capabilities. The PSI-R-SF assesses two adaptive problem-solving abilities (problem-solving self-efficacy, problem-solving skills). Previous research indicates that these two scales are consistent with the construct of social problem-solving ability (Maydeu-Olivares & D’Zurilla, 1997). In this study, total score, which was calculated by reverse-coding positive items and summing all items, was used to represent perceived social problem-solving deficits. Consistent with Heppner (1988), Form B was used in this study. In this sample, internal consistency was excellent (α=0.90).

Thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness

The 15-item INQ (Van Orden et al., 2012) was used to assess TB and PB. Similar to the INQ-18 used in Study 1, a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 7 was used. In the 15-item version, the 6-item INQ-PB ranges from 6 to 42 and the 9-item INQ-TB ranges from 9 to 63. Internal consistency was excellent for both the INQ-TB and INQ-PB (αs=0.91,0.94, respectively).

Rival mediator

The Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-2; Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996) was used to measure depressive symptom severity. The 21 items are rated on 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. In this study, a total score was generated by summing all the items except item 9, which assesses suicidal thoughts and wishes, as this item overlaps with the dependent variable. Internal consistency was excellent (α=0.90).

Statistical analyses

The approach in Study 2 was the same as that of Study 1. However, in Study 2, depressive symptoms (BDI-2) was entered as the rival mediator. With regard to the normality of residuals, one variable (DSI-SS) in this sample evidenced significant skew (Skew = 2.10; Kolmogoroz-Smirnov statistic = 0.291, p<0.001), which was addressed using MLR. Again, FIML was used to handle missing data. With a sample of 105, we were adequately powered for mediation analyses (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). In Study 2, there was also a relatively large proportion of zero responses in our outcome variable (88/105); thus, ZINB regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the proposed paths in our mediation models.

Study 2 Results

Preliminary Analyses

Study variable details are provided in Table 2. Consistent with hypotheses and Study 1, significant positive correlations emerged between perceived social problem-solving deficits and TB, PB, and suicidal ideation (r=0.22–0.33, ps<0.05).

TB and PB as Parallel Mediators

As in Study 1, when TB and PB were entered as parallel mediators of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicidal ideation, controlling for age and sex. Again, the goodness-of-fit ranged from adequate to excellent (χ2(1) = 1.03, p = 0.51; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.05 (0.03, 0.06), CFI/TLI = 0.96, 0.87; SRMR = 0.03). All α and β pathways in this mediation model were significant. The direct effect of deficits in problem-solving ability on suicidal ideation was not significant after accounting for TB and PB and the indirect effect of TB and PB on the relationship between deficits in problem-solving ability and suicidal ideation was estimated to be between 0.0035 and 0.0164, which is significant. Again, the pattern of findings remained the same after controlling for depressive symptoms and the overall regression model explained significant variance in suicidal ideation (R2=0.44, b=0.026, SE=0.002, 95%CI=0.0021, 0.0073; Figure 2B; Table 3).

Again, ZINB regression model results supported bootstrap mediation analyses. Thwarted belongingness (estimate = 0.07, SE = 0.021, p = 0.001, Wald χ2 = 22.52) and perceived burdensomeness (estimate = 0.175, SE = 0.061, p = 0.004, Wald χ2 = 18.57), individually, were both significantly associated with suicidal ideation. The model with social problem solving deficits as a predictor of suicidal ideation, controlling for age and sex, was significant, with Wald χ2 equal to 18.07, p < 0.001. Social problem-solving deficits were significantly associated with suicidal ideation (estimate = 0.029, robust SE = 0.011, p = 0.006). When thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness were included into the model, the Wald χ2 value was significant (13.67, p < 0.001). However, the main effect of social problem solving deficits on suicidal ideation was no longer significant (estimate = 0.021, SE = 0.024, p = 0.38). Again, Vuong’s test (Vuong, 1989) was not significant (p = 0.72), which does not support the ZINB model.

Specificity of TB and PB

Again, we tested for specificity. The effect of TB (β=0.008; 95%CI=−0.017, 0.011) and PB (β=0.012; 95%CI=−0.003, 0.032) on suicidal ideation was not significantly mediated by perceived social problem-solving deficits, which supports the specificity of the roles of the independent variable (perceived social problem-solving deficits) and the mediators (TB, PB). Further, depressive symptoms did not mediate the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicidal ideation, controlling for TB, PB, age and sex (b=0.0002, SE=0.002; 95%CI=−0.0031, 0.0042).

TB and PB as Individual Mediators

Finally, we evaluated TB and PB as individual mediators. When TB was entered as an individual mediator, the overall regression model was significant (R2=0.43) and the direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicidal ideation was not significant after accounting for TB (see Table 3). The indirect effect of TB was significant and estimated to be between 0.0018 and 0.0125 (R2=0.0335, κ2=0.0971). The majority of the fit statistics for this model indicated adequate fit (χ2(1) = 1.96, p = 0.27; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.09 (0.08, 0.11), CFI/TLI = 0.90, 0.79; SRMR = 0.10). Similarly, for analyses examining PB as an individual mediator, the overall regression model was significant (R2=0.44) and the direct effect was not significant after accounting for PB. The indirect effect of PB was significant and estimated to be between 0.0023 and 0.0159 (R2=0.0850, κ2=0.1639). This model exhibited excellent fit (χ2(1) = 1.81, p = 0.41; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.02 (0.01, 0.04), CFI/TLI = 0.98, 0.96; SRMR = 0.01).

Study 2 Discussion

Results from Study 2, which were consistent with Study 1 and the interpersonal theory of suicide, contributed additional support for our study hypotheses. Specifically, among another sample of undergraduate students, perceived social problem-solving deficits were associated with thwarted interpersonal needs and greater levels of suicidal thoughts. These findings are consistent with prior research findings that perceived social problem-solving deficits are correlated with suicide-related behaviors (McAuliffe et al., 2006). As before, our findings indicated that the interpersonal theory constructs provide a mechanistic explanation. In contrast to Study 1, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness were both significant individual and parallel mediators. Nonetheless, consistent with Study 1, while the model with thwarted belongingness as an individual mediator exhibited somewhat poor fit, the two-mediator model and the perceived burdensomeness-only model both exhibited excellent fit and accounted for a similar amount of variance in suicide risk. This again implies that perceived burdensomeness may be a more important indicator of risk.

Additionally, we found support for the specificity of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness as parallel mediators, as perceived social problem-solving deficits did not significantly mediate the relationship between the interpersonal theory variables and suicidal ideation, and depression did not significantly account for the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicidal ideation. Importantly, the measure of depressive symptoms used in this study exhibited excellent internal consistency, which bolsters these findings. Further, as in Study 1, the proposed pathways of the mediation models were supported by analyses accounting for the excess zeroes, which provides additional support for our findings.

Limitations of Study 2 must be acknowledged. For one, although young adults have high rates of suicidal ideation and are, thus, an important population for research, this sample was relatively high-functioning as all participants were university students; future research using samples from high-risk populations (e.g., military, inpatient) would be useful. As in Study 1, undergraduate students have more opportunities for social connection. Thus, research in samples with fewer interpersonal resources is an important next step. Finally, Study 2 used a cross-sectional design, which precludes confirmation of temporality.

Study 3: Homeless Individuals

Given that Studies 1 and 2 were limited to undergraduate students with greater opportunities for interpersonal connection, we aimed to replicate these findings among a sample of homeless individuals with a smaller network of interpersonal resources. We expected a similar pattern of findings for Study 3, such that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would serve as explanatory links.

Study 3 Method

Participants

Participants were 53 adults recruited from a Southeastern U.S. community day center that provides services, including primary and mental healthcare, to homeless individuals (see Table 1).

Procedure

All participants provided informed consent, and were compensated upon completion of a battery of questionnaires. Respondents were provided with mental health and suicide prevention resources. Of note, these data have not been previously published.

Measures

Suicide risk

The SBQ-R was used in analyses and internal consistency was good (α=0.81).

Perceived social problem-solving ability

The SPSI-R-SF was used and internal consistency was excellent (α=0.95).

Thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness

The INQ-PB and INQ-TB subscales of the INQ-15 both exhibited good-to-excellent internal consistency (αs=0.91,0.86, respectively).

Rival mediator

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke & Spitzer, 2001) is a 9-item measure of depressive symptoms. Item 9, which measures suicidal ideation and death, was removed to avoid redundancy with the dependent variable. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. Internal consistency was excellent (α=0.91).

Statistical analyses

The analytical approach remained unchanged. Missing data in this study were addressed using FIML and given the sample size of 53, we were adequately powered for mediation analyses (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). However, in this study, we were significantly underpowered to evaluate model fit indices (Wolf, Harrington, Clark, & Miller, 2013). In Study 3, although inspection of the histogram for our outcome variable did not reveal an excess of zero responses (15/53), we were underpowered (<0.80) to conduct ZINB regressions to confirm whether a zero-inflated model better fits these data.

Study 3 Results

Preliminary Analyses

See Table 2 for variable details. Significant positive correlations emerged between perceived social problem-solving deficits, TB, PB, and suicide risk (r=0.36–0.39, ps<0.05).

TB and PB as Parallel Mediators

As in Studies 1 and 2, TB and PB were first examined as parallel mediators, controlling for age and sex. As before, all α and β pathways in the mediation model were significant (Table 3). The direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for TB and PB (p=0.20). The indirect effect of TB and PB on the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk was significant and estimated to be between 0.0056 and 0.0987 (Figure 2C). Notably, the pattern of findings remained the same after accounting for depressive symptoms and the overall regression model explained a significant portion of the variance in suicide risk (R2=0.52; b=0.0456, SE=0.03, 95%CI=0.0015, 0.1017).

Specificity of TB and PB

With regard to specificity, the effect of TB (β=0.012; 95%CI=−0.021, 0.095) and PB (β=0.059; 95%CI=−0.003, 0.179) on suicide risk was not significantly mediated by social problem-solving ability, which supports the specificity of the mediators. Depressive symptoms did not mediate the relationship between social problem-solving ability and suicide risk, controlling for TB, PB, age and sex (b=−0.0037, SE=0.013; 95%CI=−0.0284, 0.0282).

TB and PB as Individual Mediators

When TB was entered as an individual mediator, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of variance in suicide risk, controlling for depression, age and sex (R2=0.50). The direct effect of social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk remained significant after accounting for TB and the indirect effect of TB was estimated to be between −0.0169 and 0.1017, which is not significant as the 95% confidence interval crossed zero. For analyses examining PB as an individual mediator, the overall regression model was significant (R2=0.53) and the direct effect of social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for PB (p=0.17). The indirect effect of PB was significant and estimated to be between 0.0070 and 0.0936 (R2=0.1257, κ2=0.2191).

Study 3 Discussion

Again, in Study 3, our results were consistent with previous research and provided support for our hypotheses. That is, among a sample of homeless individuals, perceived social problem-solving deficits were associated with more severe suicide risk and thwarted interpersonal needs. As before, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness accounted for the relationship between perceived social-problem-solving deficits and suicide risk. In this sample, individually, thwarted belongingness was not a significant mediator while perceived burdensomeness emerged as a significant mediator. The two models with perceived burdensomeness accounted for more variance in suicide risk than the model with thwarted belongingness as the main predictor. Again, these findings appear to be supportive of previous research indicating perceived burdensomeness may be more robust (Bryan et al., 2010). As in the previous studies, a rival mediator—depressive symptoms—did not demonstrate a mediating effect, highlighting the specificity of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.

This was the first study, to our knowledge, to examine the relationship between constructs of the interpersonal theory and suicide-related behaviors in a sample of homeless individuals. Findings from Study 3 are especially important given the high rates of psychiatric diagnoses and suicidal ideation and behavior among homeless individuals, particularly those with a history of mental illness (Prigerson, Desai, Liu-Mares, & Rosenheck, 2003), and the lack of research on suicidal symptoms in this population. Additionally, homeless individuals tend to have fewer interpersonal resources (Hwang et al., 2009); thus, our findings are exceptionally relevant for impacting psychological well-being in this population.

Despite replicating findings from Studies 1 and 2 in a demographically distinct sample, several limitations should be noted. Namely, the sample size used in Study 3, though adequate for bootstrap bias-corrected mediations (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007), was limited and diminished our ability to detect smaller effects, to examine any potential impact of excess zeroes on our study conclusions, and to evaluate model fit. Thus, future studies using larger samples will be needed to verify these findings in this population. Further, this sample, though high-risk and greatly understudied, may not generate generalizable findings; replication of this research in other samples is needed. Finally, as in Studies 1 and 2, Study 3 also utilized cross-sectional data, thus reducing our ability to determine the predictive validity of our hypotheses.

Study 4: Primary Care Patients

Given that Studies 1, 2, and 3 were cross-sectional, we sought to examine the predictive utility of our hypothesis in Study 4 using a longitudinal study design. Specifically, we investigated the prospective relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk in a sample of adult primary care patients. As before, we predicted that study variables would be significantly related and the interpersonal theory variables would emerge as significant parallel mediators, cross-sectionally and longitudinally.

Study 4 Method

Participants

Participants were 222 adult patients receiving treatment from a Southeastern primary care clinic located in the U.S. that serves low-income and uninsured individuals (Table 1).

Procedure

Patients completed self-report measures at baseline (Time 1; n=216–222) and at follow-up (Time 2; n=98–99). Although patients were asked to complete assessments after 6 months, the follow-up period ranged from 6 to 12 months (M=8) due to difficulties establishing contact with participants and desire to minimize the amount of missing data. All participants provided informed consent at both time points and were monetarily compensated upon study completion. Data used for Study 4 have been previously used to evaluate the links between insomnia (Chu et al., 2017) and neuroticism (Walker, Chang, & Hirsch, in press) and suicide risk.

Measures

Suicide risk

The SBQ-R was used and internal consistency was good at Times 1 and 2 (αs=0.86,0.84, respectively).

Perceived social problem-solving ability

The SPSI-SF-R was measured at Time 1 and internal consistency was excellent (α=0.93).

Thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness

The INQ-15 was used and internal consistency was good-to-excellent for the INQ-TB and INQ-PB at Time 1 (αs=0.89,0.93, respectively) and Time 2 (αs=0.89,0.94, respectively).

Rival mediator

The PHQ-9 (without item 9-suicide risk) was used to measure depressive symptoms at Time 1 and internal consistency was excellent (α=0.91).

Statistical analyses

Study 4’s analytical approach was the same as that of Studies 1, 2 and 3; however, with the longitudinal design, we were able to evaluate our hypotheses cross-sectionally at Time 1 and then prospectively, across Times 1 and 2. Further, independent t-tests were used to compare those who did and did not complete the measures at Time 2 as 124 participants did not complete Time 2. A test of missing data indicated that data were not missing at random, Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) χ2(33) = 47.21, p = 0.052. To address this issue, FIML was used to handle missing data. As our sample size ranged from 98 to 222, we were sufficiently powered for mediation analyses (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). As in Study 3, all participants in Study 4 endorsed at least some suicidal thoughts and other related risk factors, thus, our outcome variable did not exhibit an excess of zero responses at Time 1 (46/222) or Time 2 (16/98).

Study 4 Results

Preliminary Analyses

See Table 2 for details on Study 4 variables. As expected, significant positive correlations emerged between perceived social problem-solving deficits and TB, PB, and suicide risk at all time points (r=0.37–0.48, ps<0.001). Individuals who participated at Time 2 and those who only completed Time 1 did not significantly differ on demographic and key study variables at Time 1, including age (t(213)=−2.180, p=0.10), sex (t(220)=−0.67, p=0.50), ethnicity (t(219)=1.11, p=0.27), perceived social problem-solving deficits (t(219)=1.25, p=0.21), thwarted belongingness (t(214)=0.81, p=0.50), perceived burdensomeness (t(220)=0.80, p=0.42), and suicide risk (t(215)=1.40, p=0.16).

TB and PB as Cross-Sectional Parallel Mediators

First, we tested TB and PB as parallel mediators of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk cross-sectionally at Time 1, controlling for age and sex. Goodness-of-fit indices were, again, adequate to excellent (χ2(1) = 1.75, p = 0.53; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.06 (0.01, 0.10), CFI/TLI = 0.91, 0.98; SRMR = 0.05). All α and β pathways in this mediation model were significant. The direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for TB and PB (p=0.21), indicating mediation. The indirect effect of TB and PB on the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk was estimated to be between 0.0398 and 0.0801 (95%CI), indicating significance. Notably, the pattern of findings remained the same after controlling for depression and the overall model accounted for a significant amount of variance in suicide risk (R2=0.44, b=0.0224, SE=0.0084, 95%CI=0.009, 0.0431; Table 3).

Specificity of TB and PB as Cross-Sectional Mediators

With regard to mediator specificity, mediation analyses indicated that the effect of TB (β=−0.003; 95%CI=−0.054, 0.054) and PB (β<0.001; 95%CI=−0.020, 0.012) on suicide risk was not significantly mediated by social problem-solving ability, which supports the specificity of the mediators. Again, depressive symptoms also did not mediate the relationship between social problem-solving ability and suicide risk, controlling for TB, PB, age and sex (b=0.0045, SE=0.035; 95%CI=−0.002, 0.0140).

TB and PB as Cross-Sectional Individual Mediators

When TB was entered as an individual mediator, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of variance in suicide risk, controlling for depression, age and sex (R2=0.35). The direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for TB (p=0.21). The indirect effect of TB was estimated to be between 0.0110 and 0.0204 (95%CI) and was significant (R2=0.1133, κ2=0.1906). The majority of the fit statistics for this model indicated adequate fit (χ2(1) = 1.28, p = 0.46; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.08 (0.06, 0.11), CFI/TLI = 0.87, 0.85; SRMR = 0.11). When PB was entered as an individual mediator, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of variance in suicide risk, beyond depression, age, and sex (R2=0.43). The direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for PB (p=0.55) and the indirect effect of PB was significant and estimated to be between 0.0068 and 0.0374 (95%CI; R2=0.1316, κ2=0.2517). The fit statistics for this model indicated excellent fit (χ2(1) = 1.68, p = 0.30; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.07 (0.05, 0.09), CFI/TLI = 0.95, 0.94; SRMR = 0.05).

TB and PB as Prospective Parallel Mediators

Second, using a longitudinal approach, we tested TB and PB at Time 1 as parallel mediators of the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits at Time 1 and suicide risk at Time 2, controlling for suicide risk at Time 1, age and sex. Goodness-of-fit indices indicated poor to adequate (χ2(1) = 3.16, p = 0.03; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.07 (0.05, 0.09); CFI/TLI = 0.59, 0.99; SRMR = 0.16). All α and β pathways in this mediation model were significant. The direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for TB and PB (p=0.07). The indirect effect of TB and PB on the relationship between perceived social problem-solving deficits and suicide risk was estimated to be between 0.0155 and 0.0780 (95%CI;), indicating significance. When additionally controlling for depression, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of the variance in suicide risk (R2=0.28), and the indirect effect was significant (b=0.0324, SE=0.012, 95%CI=0.0111, 0.0720; Table 3; Figure 2D).

Specificity of TB and PB as Prospective Mediators

Again, mediation analyses indicated that the effect of TB (β=0.041; 95%CI=−0.005, 0.132) and PB (β=0.032; 95%CI=−0.004, 0.216) on suicide risk was not significantly mediated by social problem-solving ability, supporting the specificity of our hypothesized mediators. Depressive symptoms did not mediate the relationship between social problem-solving ability and suicide risk, controlling for TB, PB, age and sex (b=0.0066, SE=0.0071; 95%CI=−0.0021, 0.0273).

TB and PB as Prospective Individual Mediators

Finally, when TB was entered as an individual mediator, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of variance in suicide risk, controlling for depression, age and sex (R2=0.25, F[5,81]=5.34, p<0.001), the direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for TB (p=0.32), and the indirect effect of TB was significant (95%CI = 0.003, 0.0391; R2=0.1054, κ2=0.1766). Fit statistics for this model indicated adequate to good fit (χ2(1) = 1.96, p = 0.27; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.09 (0.08, 0.11), CFI/TLI = 0.90, 0.79; SRMR = 0.10). For analyses examining PB as an individual mediator, the overall regression model also explained a significant portion of variance in suicide risk (R2=0.33), the direct effect of perceived social problem-solving deficits on suicide risk was not significant after accounting for PB (p=0.84). The indirect effect of PB was significant and estimated to be between 0.0088 and 0.0629 (95%CI; R2=0.1267, κ2=0.2507). This model demonstrated excellent fit (χ2(1) = 2.01, p = 0.08; RMSEA (90%CI) = 0.06 (0.03, 0.08), CFI/TLI = 0.98, 0.95; SRMR = 0.09).

Study 4 Discussion

Consistent with Studies 1,2, and 3, Study 4 results supported our overall hypotheses. Findings highlighted that there is a cross-sectional and prospective relationship between deficits in problem-solving abilities and suicide risk. Importantly, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness provide a mechanistic explanation for this link both cross-sectionally and longitudinally, which underscores the predictive validity of our results. In this sample, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness also emerged as significant individual mediators. As in Studies 1 to 3, it is also notable that across both time points, the pattern of findings remained significant even after accounting for depression and depression was not a significant mediator, which supports the robustness and specificity of our findings.

Interestingly, the mediation model with both mediators and that with only thwarted belongingness both exhibited poor to adequate fit while the model with perceived burdensomeness as an individual mediator exhibited excellent fit. Both models that included perceived burdensomeness as a predictor, cross-sectionally and longitudinally, accounted for more variance in suicide risk than the model with only thwarted belongingness. Again, this suggests that perceived burdensomeness is a particularly important predictor of suicide risk, which is in line with recent research examining thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as longitudinal suicide risk predictors (Chu et al., 2016c; Ma et al., 2016).

This study, which extended findings to a sample of low-income, primary care patients is particularly useful, as many individuals who die by suicide visit a primary care clinician instead of a specialist mental health provider (Luoma, Martin, & Pearson, 2002). Specifically, previous research has shown that in the month prior to death, 45% of suicide decedents contacted their primary care provider and even higher rates are seen in older adult decedents (Luoma et al., 2002). This finding underscores the relevance of this setting in efforts to understand factors contributing to increased suicide risk as these settings represent key catchment areas for at-risk individuals. Although this study did not select for individuals with increased suicide risk, the number of patients in this sample who reported suicide risk on the SBQ-R (55.4%, n=123) is significantly higher compared to other studies with middle-aged and older adults, and adolescent samples, which have reported prevalence rates ranging from 1.0%–14.3% (Heisel et al., 2010; Schulberg et al., 2004; Unützer et al., 2006; Wintersteen, 2010). The severity of this sample further highlights the relevance of our findings.

Study 4’s limitations should be noted. For one, the single follow-up time point of approximately 8 months was not sufficient to capture the dynamic nature of suicidal thoughts (Bryan & Rudd, 2016) and fluctuations in thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Therefore, future research prospectively examining the role of problem-solving deficits in the etiology of suicidal thoughts and behaviors should utilize multiple time points. Relatedly, a minimum of three time points would also allow for the most conventional mediation test of interpersonal theory variables (Maric, Wiers, & Prins, 2012). It is also important to note that the sample utilized for Sample 4 was of lower socioeconomic status and, thus, caution is warranted when generalizing these findings to other sociodemographic groups.

Study 5: Military Service Members

In Study 5, we aimed to address previous limitations and extend findings from Studies 1, 2, 3, and 4 to a sample of military service members, who often have a greater prevalence and severity of suicide-related symptoms. We utilized a longitudinal study design with three time points. Again, we expected that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would emerge as significant explanatory links, cross-sectionally and longitudinally.

Study 5 Method

Participants

Participants were 329 service members recruited from four U.S. Army Medical Center-affiliated sites (details in Table 1).

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants completed baseline diagnostic interview and self-report measures. Follow-up assessments were completed five times over the course of two years. In this study, only baseline (Time 1, n=308–329), one-month (Time 2, n=251) and six-month (Time 3, n=139) follow-up data were used due to limited sample sizes at the remaining follow-up time points. Data for Study 5 were obtained as part of a larger treatment efficiency study examining young adults at high risk suicidal behaviors (i.e., referred for treatment following a suicide attempt, and/or those with a history of mood, adjustment or alcohol use disorders, and current suicidal ideation; see Rudd et al., 1996). These data have been previously used to examine problem-solving ability in the context of positive emotions (Joiner et al., 2001), mood/anxiety disorders (Joiner et al., 2003), and hopelessness and ideation (Dixon, 1994). Additionally, data for Study 5 have also been used to examine the relationship between suicidality and antisocial personality symptoms (Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, Joiner, & Rudd, 2016), negative life events (Joiner & Rudd, 2000), attempt history (Rudd, Joiner, & Rajab, 1996), the interpersonal theory (Joiner et al., 2009), a suicidal ideation scale (Joiner, Rudd, & Rajab, 1997), childhood diagnoses (Rudd, Joiner, & Rumzek, 2004), insomnia and loneliness (Hom et al., 2017).

Measures

Suicidal ideation

The Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI; Miller, Norman, Bishop, & Dow, 1986) is an 18-item clinician-administered measure of suicidal ideation in the last year. Total scores range from 0 to 54 and higher scores indicate greater suicidal symptoms. The MSSI has excellent reliability (α = 0.94), construct validity, and inter-rater reliability (Miller et al., 1986). Interrater reliability for the MSSI was unavailable in this study due to limitations in resources; however, as expected (Miller et al., 1986), the MSSI was significantly and positively correlated with self-reported depressive symptoms (BDI; r=0.45) and hopelessness (Beck Hopelessness Scale; r=0.49). In this study, internal consistency for the MSSI was good at Times 1, 2, and 3 (αs=0.88,0.89,0.86, respectively).

Social problem-solving ability

The original, 35-item PSI (Heppner, 1988; Heppner & Petersen, 1982) was used to assess social problem-solving ability. Items on the PSI are rated on a 6-point Likert scale and items assessing adaptive problem-solving approaches were reverse-scored. The total PSI score, which ranges from 35 to 210, was generated by summing all items and indicates perceived social problem-solving deficits. Again, Form B of the PSI was used (Heppner, 1988). The PSI has previously evidenced adequate-to-excellent reliability (α=0.72–0.90) and similarly, in this study, internal consistency was excellent at Time 1 (α=0.92).

Thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness