Abstract

Objective

Our objective was to systematically review randomised clinical trials (RCTs) of paediatric type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) to assess reporting of (1) primary outcome, (2) outcome measurement properties and (3) presence or absence of adverse events.

Methods

Electronic searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane SR and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases were undertaken. The search period was between 2001 and 2017. English-language RCTs on children younger than 21 years with T1DM were selected. We excluded studies of diagnostic or screening tools, multiple phase studies, protocols, and follow-up or secondary analysis of data.

Results

Of 11 816 unique references, 231 T1DM RCTs were included. Of total 231 included studies, 117 (50.6%) trials failed to report what their primary outcome was. Of 114 (49.4%) studies that reported primary outcome, 88 (77.2%) reported one and 26 (22.8%) more than one primary outcomes. Of 114 studies that clearly stated their primary outcome, 101 (88.6%) used biological/physiological measurements and 13 (11.4%) used instruments (eg, questionnaires, scales, etc) to measure their primary outcome; of these, 12 (92.3%) provided measurement properties or related citation. Of the 231 included studies, 105 (45.5%) reported that adverse events occurred, 39 (16.9%) reported that no adverse events were identified and 87 (37.7%) did not report on the presence or absence of adverse events.

Conclusion

Despite tremendous efforts to improve reporting of clinical trials, clear reporting of primary outcomes of RCTs for paediatric T1DM is still lacking. Adverse events due to DM interventions were often not reported in the included trials. Transparent reporting of primary outcome, validity of measurement tools and adverse events need to be improved in paediatric T1DM trials.

Keywords: systematic review, pediatrics, diabetes, treatment outcome, adverse events

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review that evaluates the condition of primary outcome reporting among randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of paediatric type 1 diabetes mellitus in an era post-CONSORT.

This study shows reporting of primary outcomes in RCTs conducted on diabetic children is not adequate.

Reporting of adverse events and measurement properties of outcome measures also need to be improved.

Knowledge synthesis efforts will be facilitated if heterogeneity in primary outcome selection is reduced.

This review was restricted to English language, potentially limiting generalisability of the findings to English literature.

Introduction

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the gold standard to assess efficacy of interventions.1 To ensure validity of findings in a clinical trial, it is paramount to report a clear set of outcomes, especially the primary outcomes measured, along with measurement tools used, and any assessment of adverse events. Healthcare professionals, patients, health policy developers and governments expect transparent reporting in trials to make sure the process of decision-making is well informed and less biased.2–4

The CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement, which was initially introduced in 1996 to address the problem of incomplete reporting in the published clinical trials, has been updated twice since, in 2001 and 2010.5 6 Clear reporting of a study’s primary outcome is essential, as it is used to inform the sample size calculation and is the main driver behind the trial’s purpose. If primary outcomes are not reported clearly, the results of the trial may be jeopardised. While 585 journals have endorsed CONSORT since 1996, review studies have shown that primary outcomes were explicitly defined in only 45% and 53% of trial reports that were indexed in PubMed in 2000 and in 2006, respectively.7 8 Inadequate primary outcome reporting in paediatric trials has also been reported in some previous studies.9 10 To better understand the extent of the problem across fields, we have initiated a series of systematic reviews to assess primary outcomes reporting in trials (PORTal). Our first PORTal systematic review highlighted this problem in randomly sampled paediatric RCTs and demonstrated that 27.2% of studies published in high impact journals did not specify their primary outcomes.11

Paediatric diabetes mellitus (DM) is an emerging public health concern in the 21st century12 and appropriate outcome reporting in DM trials is of great importance due to its high prevalence and economic burden worldwide.13 14 Reliable assessment of interventions on paediatric DM requires RCTs to be clearly reported.

In addition to clarity in defining primary outcomes, RCTs ought to demonstrate how they measured their primary outcome and whether their measurement tools were valid and reliable.2 Type and frequency of adverse events occurrence are also important to be studied and reported by RCTs in order to evaluate both the effectiveness of an intervention as well as possible harms associated with it.5

The primary objectives of this review were to assess RCTs of paediatric DM, published between 2001 and 2017 to evaluate reporting of (1) primary outcome, (2) measurement properties of primary outcome measure and (3) presence/absence of adverse events.

Methods

A systematic review protocol has been published at the PROSPERO website (CRD42013005224) (see online supplementary appendix 1). We followed the PRISMA guideline for conducting this systematic review.15

bmjopen-2016-014610supp001.pdf (103.6KB, pdf)

Search strategy

Electronic searches in MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane SR and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) databases were undertaken. Searches were limited to RCT study design, children under 21 years of age, English language and dated since 2001 (last update January 2017). A 5-year interval (1996–2001) since the initial publication of CONSORT was applied to our search to allow guideline implementation. The complete search strategy is available on request to the corresponding author (see online supplementary appendix 2 for MEDLINE search strategy).

bmjopen-2016-014610supp002.pdf (93.2KB, pdf)

Study selection

RCTs were selected if they were parallel, cross-over, factorial and N-of-1 trials studying type 1, and examined any medical and non-medical interventions. Studies were excluded if the population included both children and adults, and if they were diagnostic studies, part of multiphase trials, protocols, follow-up and secondary analysis of data. Title and abstracts were screened for relevant entries and then full texts of potential articles were reviewed using prespecified criteria for inclusion or exclusion. Four independent reviewers (SKA, MK, HCY, MZIH) performed study selection and discrepancies were resolved by consensus; for disagreements, a senior reviewer was sought (SV).

Data extraction

Using a standardised form, four independent reviewers performed data extraction (SKA, HCY) and verification (MK, MZIH). Collected data included journal name, publication year, design of the study, age, sex, sample size, disease condition, intervention and comparator(s) of interest, primary outcome(s), outcome measures, measurement tools and their properties, and adverse events. For more investigation, documented journal impact factors (IFs) were obtained for the year 2015 (InCites Journal Citation Reports; https://jcr.incites.thomsonreuters.com).

Full-text articles were searched for any explicit indication of primary outcome. A variety of terms for the concept of ‘outcome’ were accepted including ‘endpoint’, ‘variable’, ‘outcome variable’, ‘objective’, ‘pre-specified outcome’, ‘dependent variable’, ‘efficacy parameter’ or equivalents. If studies clearly stated their primary outcome using the mentioned terminology or described with a synonymous term anywhere in their manuscript, they were considered as ‘reported primary outcome’. We also considered them as ‘reported’ if they explicitly stated the outcome used for the sample size calculation. If studies provided several outcomes without specifying their primary, we considered them as ‘failed to report primary outcome’. After identifying the primary outcome, if it was not a biological/physiological measure (eg, blood tests), we sought for its measurement tool and reporting of measurement properties (validity and reliability), in addition to any relevant citation(s). Furthermore, any assessment of presence or absence of adverse events (and other relevant terms) was documented. If a study did not report at all on adverse events (its presence or absence), we classified that as ‘failed to report adverse events of intervention’.

Data analysis

Using descriptive analysis, we presented percentages, mean, median, range and IQR for the primary outcome and adverse events. Since this systematic review focused on reporting status of primary outcome and adverse events in published RCTs and was not intended to evaluate the effectiveness or efficacy of the interventions, the risk of bias and meta-analysis were not part of our study. Considering journals’ impact factor (IF) for each published RCT, we grouped them into three batches using first quartile (Q1), interquartile range (Q3–Q1) and last quartile (Q4) of all IFs; journals with no available IF were coded as unknown. χ2 test was performed for finding the differences between proportions of reporting primary outcome and adverse events among low, medium and high impact factor journals using Stata statistical software release 14.16

Patient involvement

Patients were not involved in the design and conduct of this study as the present study was a systematic review of published RCTs.

Results

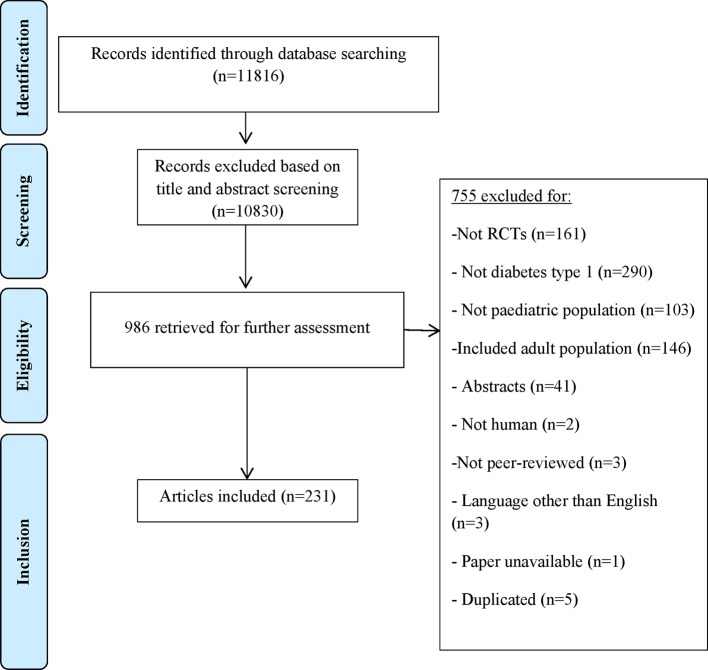

Our electronic search yielded 11 816 unique references; full texts of 986 potentially relevant studies were retrieved for inclusion/exclusion. Seven hundred and fifty-five out of 986 retrieved articles were excluded; reasons for exclusion are presented in the PRISMA flow diagram (figure 1). Finally, 231 RCTs of paediatric T1DM were included for this systematic review.

Figure 1.

Adapted version of PRISMA flow diagram of study selection. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Type 1 diabetes mellitus

Of 231 RCTs, 177 (76.6%) had parallel and 54 (23.4%) had cross-over groups design. Total population was 21 014 and sample sizes ranged from 7 to 689 participants (median: 51.5, IQR 30–110.75). Other general characteristics of the studies are summarised in table 1. Interventions comprised different forms of insulin therapy, oral medications, dietary, educational and other medical interventions for glucose monitoring and insulin delivery methods.

Table 1.

General characteristics of the included studies

| RCTs’ characteristics | Diabetes type 1 RCTs (n=231) |

|

| Journals’ impact factor | High (≥8.42) | 59 (25.5) |

| Medium (≥2.57 and <8.42) | 115 (49.8) | |

| Low (<2.57) | 42 (18.2) | |

| Unknown | 15 (6.5) | |

| Age range | Range of actual age (years) | 1–21 |

| Range of mean (years) | 2.9–17.7 | |

| Type of design | Parallel | 177 (76.6) |

| Crossover | 54 (23.4) | |

| Sample size | Range | 7–689 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean: 91.37 (103.38) | |

| Median (IQR) | Median: 51.5 (30–110.75) | |

| Type of intervention | Insulin/drug based | 91 (39.4) |

| Diet based | 21 (9.1) | |

| Education based | 41 (17.7) | |

| Other medical intervention | 17 (7.4) | |

| Others | 61 (26.4) | |

| Controls | Placebo | 29 (12.5) |

| Usual care/no treatment/waitlist | 97 (42) | |

| Other treatment | 105 (45.5) |

Data are presented as n (%).

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Primary outcomes

Of 231 RCTs, 114 (49.4%) studies explicitly identified their primary outcome while 117 (50.6%) did not. Of the 114 studies that transparently reported a primary outcome, 88 (77.2%) reported one primary outcome, 18 (15.8%) reported two primary outcomes and 8 (7%) identified between three and seven primary outcomes. Among studies with a single primary outcome (n=88), 83 (94.3%) were biological/physiological measurements, and the rest (n=5, 5.7%) were non-physiological (table 2). Overall, these trials used 14 uniquely different primary outcomes. Out of 88 studies with single primary outcomes, 48 (54.5%) measured haemoglobin-A1C and 24 (27.3%) measured blood glucose levels.

Table 2.

Frequency and type of primary outcomes in clinical trials of type 1 diabetes mellitus

| Outcome categories | Primary outcomes | Frequency,* n (%) |

| Physiological measures | HbA1C levels | 48 (54.5) |

| Blood glucose levels | 24 (27.3) | |

| C-peptide levels | 4 (4.5) | |

| Endothelial function | 2 (2.3) | |

| Time to metabolic normalisation | 1 (1.14) | |

| Fructosamine levels | 1 (1.14) | |

| Insulin sensitivity | 1 (1.14) | |

| Change in creatinine clearance rate | 1 (1.14) | |

| Epinephrine response to hypoglycaemia | 1 (1.14) | |

| Non-physiological measures | Treatment fidelity | 1 (1.14) |

| Perceived diabetes self-efficacy | 1 (1.14) | |

| Preference for NovoTwist versus screw-thread needles in children and adolescents | 1 (1.14) | |

| Health-related quality of life | 1 (1.14) | |

| Macronutrient and micronutrient composition of different diets | 1 (1.14) |

*Some studies used more than one primary outcome.

HbA1c, haemoglobin-A1c.

Outcome measures

Of 114 studies that clearly defined their primary outcome, 101 (88.6%) used biological/physiological measurements including measurements of glycaemic control (eg, haemoglobin-A1c, blood glucose). Thirteen (11.4%) trials used an outcome measurement instrument to measure their primary outcome. Of these 13, 5 provided both measurement properties and citation for the instruments used, 7 provided only the citation and 1 provided neither.

Adverse events

Of 231 studies, 105 (45.5%) reported adverse event(s) associated with the intervention under study, 39 (16.9%) reported the absence of adverse events and 87 (37.7%) failed to report on the presence/absence of adverse events.

Journals’ impact factor and consort endorsement

Based on quartiles of journals’ IFs, three levels of low (IF <2.57), medium (2.57≥IF<8.42) and high (IF ≥8.42) were established. There was no statistically significant difference among studies published in low, medium and high IF journals regarding adverse event reporting (p=0.7). However, failing to report primary outcome was associated with publishing in low IF journals (p=0.04) (table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency distribution of primary outcome and adverse event reporting by journals’ impact factors (IF)

| IF | Low (n=42)* | Medium (n=115) | High (n=59) | χ2 test | |

| Primary outcome | Reported (n=114) | 14 (12.3)† | 64 (56.1) | 31 (27.2) | p=0.04 |

| Failed to report (n=117) | 28 (23.9) | 51 (43.6) | 28 (23.9) | ||

| Adverse events | Reported (n=144) | 25 (17.4) | 76 (52.8) | 39 (27.1) | p=0.7 |

| Failed to report (n=87) | 17 (19.5) | 39 (44.8) | 20 (22.9) | ||

*Low IF (<2.57), medium IF (2.57≥IF< 8.42) and high IF (≥8.42).

†All data are presented as n (%).

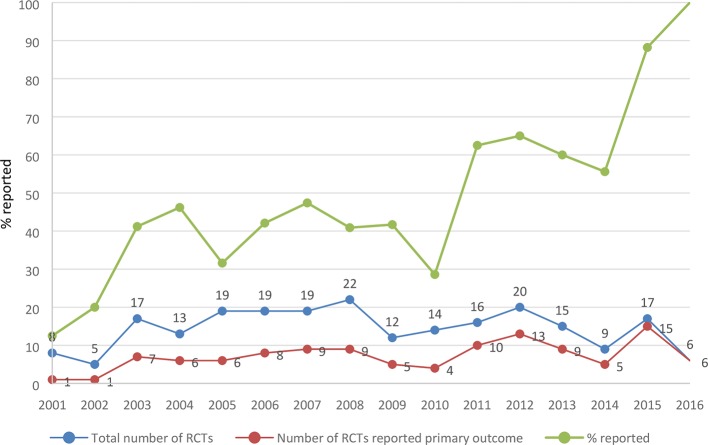

Considering the date of publication, an upward trend was observed in reporting primary outcome(s) over time (figure 2). However, endorsing CONSORT guideline did not influence the reporting of primary outcomes. Of 231 included trials, 108 (46.8%) were published in CONSORT-endorsing journals. Among those, 57 (52.8%) reported their primary outcome, while 57 (46.3%) of 123 trials published in non-endorsing CONSORT journals reported a primary outcome (p=0.3).17

Figure 2.

Proportion of studies that reported primary outcome(s) by year of publication. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Discussion

This is the first study to present a comprehensive overview of primary outcome and adverse events reporting among published RCTs in paediatric T1DM. As RCTs are recognised for their importance in medical research, methodological examinations of their reports are crucial for appropriate medical practice.18

It has been 20 years since the initial CONSORT statement recommended guidelines for minimal necessary RCT reporting. Since then, reporting of study rationale, objective, recruitment methods, sample size calculation, allocation concealment and method of sequence generation have been improving among published clinical trials.19 Nevertheless, we and other groups have shown that reporting of primary outcome, measurement tools and reporting of the validity and reliability of those tools have not been improved alike.7 20–22 A systematic review performed on a random sample of paediatric RCTs published in high impact CONSORT-endorsing journals reported that 27.2% of the trials failed to report any primary outcome.11 In our analysis, we demonstrated suboptimal reporting of primary outcomes and adverse events of interventions in journals with high and low impact factor, regardless of whether they endorsed the CONSORT guideline or not. We were quite flexible regarding author terminology used to describe primary outcomes in articles. Given that, if authors did not explicitly specify their primary outcome(s), we considered this issue as a failure in reporting. Failure in reporting primary outcome(s) may lead to selective outcome(s) reporting23; CONSORT and its extensions were intended to prevent biased reporting by ensuring primary outcomes are clearly and explicitly stated in all peer-reviewed published RCTs. This also influences the qualitative evaluation of RCTs in systematic reviews and meta-analyses using existing risk of bias tools.24 Furthermore, heterogeneous outcomes challenge knowledge synthesis efforts to summarise data between trials and maximise its use in decision-making.

DM lends itself to use of biological/physiological measurements. Accuracy in the measurement of these biological or physiological assessments is outside our scope, but we are reassured that the other instruments used (eg, surveys) had appropriate citations regarding their measurement properties (reliability, validity). Furthermore, we found heterogeneity in primary outcomes used in our included studies (only half of them used similar primary outcomes). According to the COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative,25 consistency in primary outcome measurement between trials is necessary to allow for meaningful knowledge synthesis. Most systematic reviews try to assess treatment effectiveness by compiling evidence from multiple RCTs; however, these efforts are hampered by heterogeneity in outcome measurement.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this systematic review is unique in that it has evaluated the condition of primary outcome reporting among RCTs of paediatric T1DM in an era post-CONSORT. A robust and systematic methodology was employed including independent and duplicate screening/data extraction using prespecified criteria and data extraction form. This review was a complement to our previous work that examined a random sample of all paediatric RCTs published in high-profile peer-reviewed journals.11 We further examined primary outcome and adverse event reporting on the basis of high, medium and low impact factor journals.

As a possible limitation, this review was restricted to English language, potentially limiting generalisability of the findings to English literature.

Implications

The results of this systematic review underscore the potential opportunities for improving the quality of reporting in paediatric clinical trials. It is important for journals that endorse CONSORT to ensure that authors and reviewers use the checklist to confirm reporting of main components of RCTs is complete and transparent. Paediatric DM is an important condition with increasing prevalence and will have a global impact on health. To be of most use to clinicians and policy-makers, trials in this field would benefit from improved reporting of primary outcomes and adverse events. In addition, development of a core outcome set (to reduce heterogeneity in primary outcome measurements) and using outcome measurement instruments that are valid and reliable and reported as such are of great importance to support quality meta-analysis leading to more precise and unbiased findings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Each author contributed substantially to (1) conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) final approval of the version to be published and (4) agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. SKA was substantially involved in design and conduct of the study, screening articles, extracting the data, interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published. MK was substantially involved in the conduct of the study, screening articles, extracting the data, interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published. HCY was substantially involved in screening articles, extracting the data, revising the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. MZIH was substantially involved in screening the articles, extracting the data, revising the manuscript and final approval of the version to be published. SV was substantially involved in design and conduct of the study, interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the manuscript, and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The complete search strategy is available on request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:726–32. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinha I, Jones L, Smyth RL, et al. . A systematic review of studies that aim to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials in children. PLoS Med 2008;5:e96 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha IP, Altman DG, Beresford MW, et al. . Standard 5: selection, measurement, and reporting of outcomes in clinical trials in children. Pediatrics 2012;129:S146–52. 10.1542/peds.2012-0055H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van’t Hoff W, Offringa M, Star Child Health group. StaR Child Health: developing evidence-based guidance for the design, conduct and reporting of paediatric trials. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:189–92. 10.1136/archdischild-2012-303094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. . CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:e1–37. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman D, et al. . The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA 2001;285:1987–91. 10.1001/jama.285.15.1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan AW, Altman DG. Epidemiology and reporting of randomised trials published in PubMed journals. Lancet 2005;365:1159–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71879-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM, et al. . The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed. BMJ 2010;340:c723 10.1136/bmj.c723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clyburne-Sherin AV, Thurairajah P, Kapadia MZ, et al. . Recommendations and evidence for reporting items in pediatric clinical trial protocols and reports: two systematic reviews. Trials 2015;16:417 10.1186/s13063-015-0954-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crocetti MT, Amin DD, Scherer R. Assessment of risk of bias among pediatric randomized controlled trials. Pediatrics 2010;126:298–305. 10.1542/peds.2009-3121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhaloo Z, Adams D, Liu Y, et al. . Primary outcomes reporting in trials (PORTal): a systematic review of inadequate reporting in pediatric randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;81:33–41. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature 2001;414:782–7. 10.1038/414782a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson C, Guariguata L, Dahlquist G, et al. . Diabetes in the young—a global view and worldwide estimates of numbers of children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014;103:161–75. 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazeli Farsani S, van der Aa MP, van der Vorst MM, et al. . Global trends in the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents: a systematic review and evaluation of methodological approaches. Diabetologia 2013;56:1471–88. 10.1007/s00125-013-2915-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg 2010;8:336–41. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.StataCorp. Statistical Software, Release 2014. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.CONSORT Transparent Reporting of Trials. Statement endorsers: Council of Science Editors, International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), World Association of Medical Editors (WAME), 2016. http://www.consort-statement.org/about-consort/endorsers#n.

- 18.Agha R, Cooper D, Muir G. The reporting quality of randomised controlled trials in surgery: a systematic review. Int J Surg 2007;5:413–22. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2007.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. . Does use of the CONSORT Statement impact the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials published in medical journals? A Cochrane review. Syst Rev 2012;1:60 10.1186/2046-4053-1-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blakely ML, Kao LS, Tsao K, et al. . Adherence of randomized trials within children’s surgical specialties published during 2000 to 2009 to standard reporting guidelines. J Am Coll Surg 2013;217:394–9. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston BC, Shamseer L, da Costa BR, et al. . Measurement issues in trials of pediatric acute diarrheal diseases: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2010;126:e222–31. 10.1542/peds.2009-3667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anttila H, Malmivaara A, Kunz R, et al. . Quality of reporting of randomized, controlled trials in cerebral palsy. Pediatrics 2006;117:2222–30. 10.1542/peds.2005-1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG, et al. . The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 2010;340:c365 10.1136/bmj.c365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook on systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. Oxford: Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gargon E. The COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) initiative. Maturitas 2016;91:91–2. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014610supp001.pdf (103.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014610supp002.pdf (93.2KB, pdf)