We demonstrate the first reported methodology using nanowires that unveils massive numbers of cancer-related urinary microRNAs.

Abstract

Analyzing microRNAs (miRNAs) within urine extracellular vesicles (EVs) is important for realizing miRNA-based, simple, and noninvasive early disease diagnoses and timely medical checkups. However, the inherent difficulty in collecting dilute concentrations of EVs (<0.01 volume %) from urine has hindered the development of these diagnoses and medical checkups. We propose a device composed of nanowires anchored into a microfluidic substrate. This device enables EV collections at high efficiency and in situ extractions of various miRNAs of different sequences (around 1000 types) that significantly exceed the number of species being extracted by the conventional ultracentrifugation method. The mechanical stability of nanowires anchored into substrates during buffer flow and the electrostatic collection of EVs onto the nanowires are the two key mechanisms that ensure the success of the proposed device. In addition, we use our methodology to identify urinary miRNAs that could potentially serve as biomarkers for cancer not only for urologic malignancies (bladder and prostate) but also for nonurologic ones (lung, pancreas, and liver). The present device concept will provide a foundation for work toward the long-term goal of urine-based early diagnoses and medical checkups for cancer.

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) inside extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies (1–4) [where some authors have used EVs additionally to encompass all membrane vesicles, including the three types of vesicles with microsomes (4, 5)], with diameters of 40 to 5000 nm, have been found in various body fluids of both healthy subjects and patients with malignant diseases (6–20). The difference in the EV-encapsulated miRNAs between the two groups of people may represent a warning sign for various disease scenarios (20). Because EV encapsulation of miRNAs has an advantage of being able to lower the ribonuclease effect on RNA degradation (21), the miRNAs inside the EVs are much more stable than free-floating RNAs. This promotes a switch from free-floating miRNA analysis to EV-encapsulated miRNA analysis.

Conventionally, three major methodologies have been used for EV collection (4): ultracentrifugation or differential centrifugation, immunoaffinity-based capture, and size exclusion chromatography. Some emerging methodologies have been reported as promising alternatives, including polymer precipitation (22), microfluidic-based platforms (23–26), and size-based filtration (27). However, none of the existing methodologies for collecting EV-encapsulated miRNAs have satisfied the requirements for simple and noninvasive urine-based early disease diagnoses and timely medical checkups. This is because the concentration of EVs in urine is extremely low (<0.01 volume %) (28). For example, ultracentrifugation as the most commonly used method has allowed researchers to collect urine EVs, perform the following extraction of EV-encapsulated miRNAs (29, 30), and identify 200 to 300 urinary miRNAs (31). Although more than 2000 human miRNAs have been discovered, it is unclear whether the other 90% of the miRNA species do not present in urine because of their tissue-specific functions or because they are simply undetectable by the ultracentrifugation method due to their low abundance. The second assumption presents a motivation for researchers to realize urine-based early disease diagnoses and timely medical checkups using the urinary miRNAs; the small population of identified urinary miRNAs cannot reflect the variety of diseases possible. An alternative methodology is needed.

Here, we propose a nanowire-based methodology for collecting urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs that unveils massive numbers of urinary miRNAs of different sequences. This methodology moves researchers toward the goal of miRNA-based noninvasive and simple early disease diagnoses and timely medical checkups from urine. Although nanowires have shown great potentials for analyzing properties of cells or intracellular components (32–39), none of the previous studies have dealt with applications to collect EVs. We consider utilization of a surface charge, a relatively large surface area, and mechanical stability of the nanowires within a microchannel. This methodology essentially allows us to perform EV-encapsulated miRNA analysis with a small sample volume and short treatment time; that is, collecting the EVs requires only 1 ml of urine and 20 min. The mechanical stability of nanowires anchored into poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) during lysis buffer flow is effective for efficient in situ extraction of the urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs within 20 min; more species of miRNAs of different sequences (around 1000 types) can be extracted from collected EVs than by conventional methods.

RESULTS

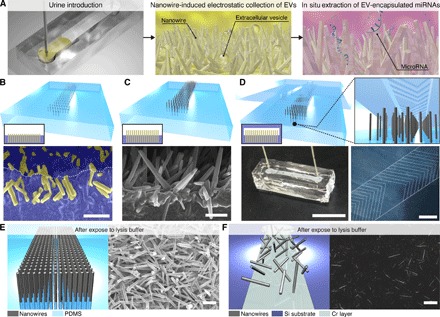

To realize our methodology for collecting urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs, we developed nanowires that were anchored into microfluidic substrates; these nanowires can play an important role as a solid phase for electrostatic collection of EVs followed by in situ extraction of EV-encapsulated miRNAs (Fig. 1A and movie S1).

Fig. 1. Nanowire-induced electrostatic collection of urine EVs followed by in situ extraction of EV-encapsulated miRNAs.

(A) Schematic illustrations for urine EV collection and in situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs using a nanowire-anchored microfluidic device. (B) A schematic illustration (gray rods, nanowires; transparent cyan areas, PDMS) and an inset illustration on the lower left showing a cross-sectional image (yellow and blue represent nanowires and PDMS, respectively) for buried nanowires after poring, curing, and peeling off PDMS, and a vertical cross-sectional FESEM image of buried nanowires; nanowires and PDMS are highlighted as yellow and blue, respectively, and the white dotted line indicates a PDMS edge. Scale bar, 1 μm. (C) A schematic illustration and an inset illustration on the lower left showing a cross-sectional image for growing nanowires from the buried nanowires (nanowire-embedded PDMS), and a vertical cross-sectional image of the nanowire-embedded PDMS. Scale bar, 1 μm. (D) A schematic illustration and an inset illustration on the lower left showing a cross-sectional image for bonding the nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate to the microfluidic herringbone-structured PDMS substrate, an image of the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device (bonding the nanowire-embedded PDMS and the microfluidic herringbone-structured PDMS substrates) with PEEK tubes for an inlet and an outlet (scale bar, 1 cm), and a laser micrograph of the microfluidic herringbone structure on PDMS (scale bar, 1 mm). (E) A schematic illustration of the nanowire-embedded PDMS (gray rods, nanowires; transparent cyan areas, PDMS), and an overview of FESEM image for the nanowire-embedded PDMS (scale bar, 1 μm) after being exposed to lysis buffer. (F) A schematic illustration of nanowires on the Si substrate (gray rods, nanowires; dark cyan areas, Si substrate; faded cyan areas, Cr layer), and an overview of FESEM image for the nanowires on the Si substrate after being exposed to lysis buffer. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate

We fabricated the nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate in four steps (40) (fig. S1): First, we grew nanowires from a thermally oxidized chromium layer on Si substrates; second, we poured uncured PDMS onto the grown nanowires; third, we buried nanowires into the PDMS after curing and peeling off the PDMS with the nanowires (Fig. 1B); and fourth, we grew nanowires from the buried nanowires, which we named as the nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate (Fig. 1C). Vertical cross-sectional field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images of the buried nanowires demonstrated that nanowires were uniformly and deeply buried into PDMS with their heads slightly emerged (Fig. 1B), and the heads provided growth points for the second nanowire growth (Fig. 1C and fig. S2). Comparing the energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping of a cross-sectional FESEM image for nanowire-free PDMS with that for nanowire-buried PDMS (fig. S3), we confirmed that ZnO nanowires were buried into PDMS. In addition, a vertical cross-sectional and an overview FESEM image and EDS elemental mapping of a cross-sectional FESEM image showed that the second nanowire growth occurred at the buried nanowires; hence, we had successfully fabricated the nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate. To enhance contact events between the nanowires and the EVs and to avoid any pressure drop events, we used a microfluidic herringbone-structured (41) PDMS substrate, which ensures good convection and diffusion of solutions, with a larger channel height (50 μm) than the nanowire length (2 μm) as a cover for the nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate (Fig. 1D). A nanowire-anchored microfluidic device for in situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs was finalized by bonding the nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate to the microfluidic herringbone-structured PDMS substrate and connecting polyether ether ketone (PEEK) tubes for introducing and collecting urine samples (Fig. 1D). The nanowires anchored into PDMS showed mechanical stability when exposed to lysis buffer, thus preventing nanowires peeling off from the substrates as occurred for the nonanchored nanowires (Fig. 1, E and F, and fig. S4).

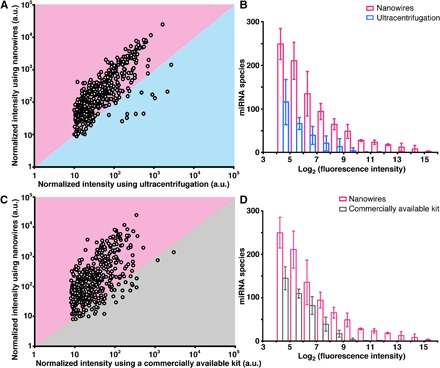

Microarray analysis of miRNA expression

Microarray analysis of miRNA expression (2565 types) showed that in situ extraction using the device provided a greater variety of species of miRNAs (around 1000 types) compared to the conventional ultracentrifugation method or a commercially available kit (ExoQuick-TC, polymeric precipitation method) (Fig. 2 and fig. S5A). In situ extraction within 40 min (collection, 20 min; extraction, 20 min) of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs was demonstrated by introducing 1 ml of urine sample followed by 1 ml of lysis buffer into the device. In comparison, the miRNA extraction from the ultracentrifuged EVs of 20 ml of urine was demonstrated by suspending the EVs in 1 ml of lysis buffer, and this required more than 5 hours for collection and extraction. Because it has been reported that the kit showed superiority to other EV isolation methods in terms of small RNA yield (fig. S5, B and C) (22), we also demonstrated the miRNA extraction from the collected EVs of 1-ml urine using the kit by suspending the EVs in 1 ml of lysis buffer, and this required more than 14 hours for collection and extraction. The scatterplot and histogram revealed that the miRNA expression level from the device was much higher than that from ultracentrifugation (Fig. 2, A and B), despite the fact that the consumed volume of urine for the device was 20 times less. Normally, the miRNA expression level from ultracentrifugation should be higher than that from the device due to the 20 times larger volume; however, the results were completely opposite: Compared to ultracentrifugation, the device showed a fivefold higher miRNA expression level (Fig. 2A) and a greater variety of extracted species of miRNAs (749, 822, and 1111 types versus 171, 261, and 352 types) (Fig. 2B). Moreover, the scatterplot and histogram revealed that the miRNA expression level from the device was much higher than that from the kit (Fig. 2, C and D), despite the fact that the consumed volume of urine for the device was the same as that of the kit. The device showed a fourfold higher miRNA expression level (Fig. 2C) and a larger variety of extracted species of miRNAs (749, 822, and 1111 types versus 337, 355, and 491 types) (Fig. 2D). We concluded that our methodology was superior to other methodologies regarding miRNA extraction efficiency (Fig. 2), treatment time (fig. S5, A and B), and small RNA extraction efficiency (fig. S5C).

Fig. 2. In situ extraction of miRNAs using the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device.

(A) Scatterplot of normalized intensities of miRNAs extracted from the collected EVs on nanowires in the device versus the ultracentrifuged EVs. Each point corresponds to a different miRNA type (that is, species). The boundary between pink and cyan represents the same level of miRNA expression for the two approaches. (B) Histogram of miRNA species for nanowires (pink) and ultracentrifugation extraction (cyan). Error bars show the SD for a series of measurements (n = 3). (C) Scatterplot of normalized intensities of miRNAs extracted from the collected EVs using the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device versus miRNA expression extracted from the collected EVs when using a commercially available kit. Each point corresponds to a different miRNA type (species). The boundary between pink and gray represents the same level of miRNA expression for the two approaches. (D) Histogram of miRNA species for nanowires (pink) and the commercially available kit (gray). Error bars show the SD for a series of measurements (n = 3). a.u., arbitrary units.

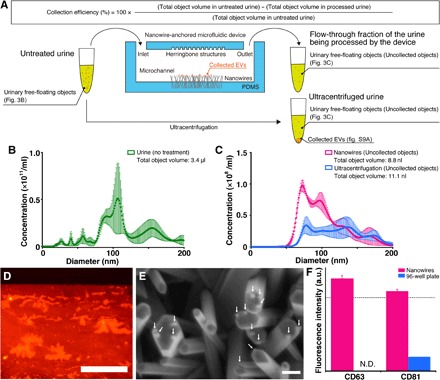

EV collection capability

To elucidate that in situ extraction using the device could provide a much larger variety of species of miRNAs, we confirmed the capability of the device to collect EVs; the device showed highly effective EV collection (Fig. 3). Considering that the total volumes of urinary free-floating objects in the untreated urine, in the flow-through fraction of the urine being processed by the device (input volume, 1 ml), and in the ultracentrifuged urine (input volume, 20 ml) were 3.4 μl, 8.8 nl, and 11.1 nl, respectively, we estimated the collection efficiency of the objects on the device to be more than 99% and that volume was larger than the volume achieved by ultracentrifugation (collected EV volume was calculated by subtracting object volume in processed urine from its volume in untreated urine) (Fig. 3, A to C). After observing fluorescently labeled EVs, we obtained their FESEM images by peeling the nanowire-embedded PDMS off the microfluidic herringbone-structured PDMS substrate; these observed results allowed us to confirm that the free-floating objects collected by the nanowires included EVs (Fig. 3, C and D). To further confirm whether the free-floating objects collected by the nanowires included EVs, we detected CD63 and CD81 membrane proteins expressed on the EVs; these are well-known membrane proteins expressed on exosomes (2, 42–44). Fluorescence intensity from collected urine EVs (concentration, 1.4 × 108 ml−1) onto nanowires or plate wells of a 96-well plate showed that only nanowires could detect the membrane proteins (Fig. 3E). Significantly, this indicated the efficient collection of EVs onto the nanowires in the device. We prepared ZnO/Al2O3 core-shell nanowires by covering the ZnO nanowires with about a 10-nm-thick Al2O3 layer (fig. S6), which resulted in a nearly neutrally charged surface (that is, slightly positive or slightly negative) at pH 6 to 8 due to the isoelectric point value of Al2O3 (ca. 7.5) (45, 46). We used these ZnO/Al2O3 core-shell nanowires to roughly estimate that the nanowire surface charge was the dominant effect for EV collection (fig. S7). Because urine EVs have a negatively charged surface at pH 6 to 8 (fig. S8), it makes sense that the ZnO nanowires with a relatively large surface area and a positively charged surface at pH 6 to 8 due to the isoelectric point value of ZnO (ca. 9.5) (47, 48) could achieve highly efficient EV collection. These results highlighted the idea that ZnO nanowires could collect urinary free-floating objects with diameters up to 200 nm, including EVs, with more than 99% collection efficiency.

Fig. 3. EV collection onto the nanowires.

(A) A schematic illustration for the experimental process and calculation of collection efficiency. (B) Size distribution of the urinary free-floating objects in the untreated urine. Error bars show the SD for a series of measurements (n = 3). (C) Size distribution of the urinary free-floating objects in the flow-through fraction of the urine being processed by the device (pink) and in the ultracentrifuged urine (cyan). Error bars show the SD for a series of measurements (n = 3). (D) Fluorescently (PKH26) labeled EVs collected on nanowires. Red denotes PKH26-labeled EVs on nanowires. Scale bar, 500 μm. (E) An FESEM image of nanowires after introduction of PKH26-labeled EVs. White arrows indicate collected EVs. Scale bar, 200 nm. (F) Detection of EVs in urine on nanowires (pink) and a 96-well plate (cyan) using an antibody of CD63 or CD81. The measured concentration of the urinary free-floating objects was 1.4 × 108 ml−1. N.D. indicates fluorescence intensity was not detected. The black dotted line shows the signal level at 3 SD above the background. Error bars showing the SD for a series of measurements of nanowires and a 96-well plate (n = 24 and 3, respectively).

Benefit of nanowire-based collection

Regarding the reason why in situ extraction using the device was superior to ultracentrifugation extraction or kit-based extraction, we considered two possible scenarios: In the first scenario, the device could collect exosomes and microvesicles, and in the second, only the device could collect EV-free miRNAs. The measured concentration and volume obtained from adding the objects collected by ultracentrifugation, that is, the exosomes (9.0 nl; fig. S9A), to the uncollected objects (11.1 nl; Fig. 3C) seemed inconsistent with their calculated concentration and volume (3.4 μl; Fig. 3B). This implied that ultracentrifugation could collect mainly exosomes (4, 5, 29), although there is still discussion that current purification methods do not allow full discrimination between exosomes and microvesicles (1). Ultracentrifugation might have a tendency to fuse and rupture most microvesicles by pressing them to the interior walls of the ultracentrifugation tubes, and this process would force microvesicles to release miRNAs into the surrounding solution. Because the EV collection mechanism by ultracentrifugation is based on a balance between applied forces and density of the collected objects, the experimental conditions for ultracentrifugation do not allow for the collection of released miRNAs. On the other hand, the collection mechanism by nanowires is based on electrostatic interactions between positively charged nanowires and negatively charged objects; the nanowires could collect exosomes and microvesicles. Furthermore, the capability of nanowires to collect EV-free miRNAs was conceivable because nucleic acids, including miRNAs, are known to have a negatively charged surface property at pH 6 to 8; for ultracentrifugation and the kit, this was impossible. Although the collection efficiency of miRNAs onto nanowires was not satisfactory, the recovery rate by introducing lysis buffer was almost 100% (fig. S9B). The positively charged surface nanowires would provide a considerable benefit for collecting negatively charged objects in urine, including exosomes, microvesicles, and EV-free miRNAs.

Considering the features of collection efficiency, selectivity of obtained sample, and ability to collect urinary miRNAs (Table 1), we concluded that the device offers high collection efficiency, low sample selectivity (exosomes, microvesicles, and EV-free miRNAs), and high collection ability; ultracentrifugation offers low collection efficiency, high sample selectivity (only exosomes), and low collection ability; and the kit provides the three features at intermediate levels (probably exosomes and microvesicles). Compared to the charge-based isolation approach for EVs (49), by which protamine precipitation of EVs is performed using protamine/polyethylene glycol in an overnight incubation at 4°C (similar to ExoQuick), we can say that our device has an advantage of providing 40-min in situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs (collection, 20 min; extraction, 20 min) at room temperature. Moreover, compared to the charge-based isolation approach for free nucleic acid (50), which uses chitosan polymer with amine groups that provide a positively charged surface only below pH 6.3, we can say that our device has an advantage of an assured positively charged surface at pH 6 to 8 of urine. Although the exact collection mechanism of EVs by nanowires in the present work must be rather complex, our findings indicated that the mechanically stable anchoring of nanowires anchored into PDMS during lysis buffer flow and the electrostatic collection of EVs (and, moreover, EV-free miRNAs) onto ZnO nanowires were two key mechanisms, and they will lead to realization of early disease diagnoses and timely medical checkups based on urine miRNA analysis.

Table 1. Comparison among three methodologies.

| Fabricated device | ExoQuick | Ultracentrifugation | |

| Collected objects | Exosomes Microvesicles EV-free miRNAs |

Exosomes Microvesicles |

Exosomes |

| Collection mechanism | Electrostatic interaction between nanowire surface charge and collected objects |

Polymer-based capture of objects ranging from 60 to 180 nm in diameter, according to the kit manufacturer’s instruction manual |

Balance between applied forces and density of the collected objects |

| Sample volume | 1 ml | 1 ml | 1 ml for small RNA quantification 20 ml for urinary miRNA profiling |

| Processing time | 40 min | 870 min | 300 min |

| Collection efficiency (small RNA yield) | 0.194 ± 0.028 ng/μl | 0.120 ± 0.015 ng/μl | 0.159 ± 0.077 ng/μl |

| Extraction species of urinary miRNAs being identified |

749, 822, 1111 (n = 3) | 337, 355, 491 (n = 3) | 171, 261, 352 (n = 3) 200 to 300* |

*From Cheng et al. (31).

Finding undiscovered miRNAs from urine samples of various cancer donors

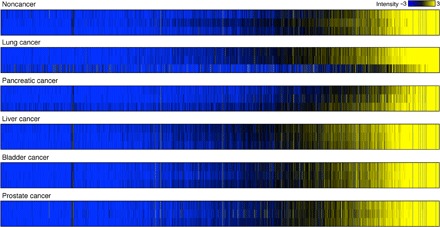

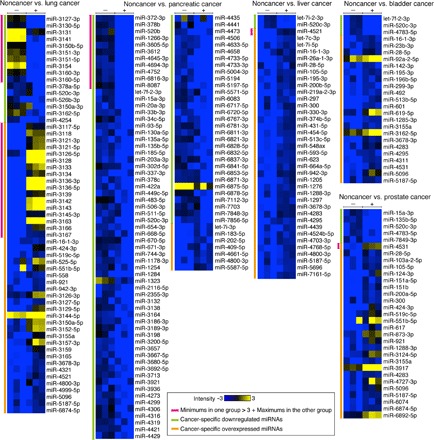

Finally, we demonstrated the potential of in situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs using the device to find previously undiscovered miRNAs from urine samples of various cancer donors (Fig. 4). Because the device allowed us to analyze many species of miRNAs from a 1-ml urine sample, we compared a heat map of miRNA expression for cancer and noncancer donor urine samples. To the best of our knowledge, we have reported the first case of unveiling massive numbers of potential cancer-related miRNAs of different sequences in 1-ml urine samples. miRNAs from urine samples had different expression levels; comparison between cancer and noncancer donor urine samples showed some down-regulated and overexpressed miRNAs (Fig. 5 and Table 2). The heat maps suggested that a combination of some down-regulated and overexpressed miRNAs could be a candidate for a new cancer indicator, which is contrary to the stereotype thinking of depending on a single miRNA biomarker.

Fig. 4. In situ extraction of cancer-related miRNAs using the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device; heat maps of the miRNA expression array for noncancer lung, pancreatic, liver, bladder, and prostate cancer donor urine samples (n = 3).

For intuitive understanding of the expression level of each miRNA and easy comparison between each group, we used color gradations showing signal intensity variation. Black, logarithmic signal intensity of 5; blue, logarithmic signal intensity less than or equal to 2; and yellow, logarithmic signal intensity greater than or equal to 8. Each column in the heat maps represents the logarithmic signal intensities of each miRNA corresponding to the color gradation.

Fig. 5. Down-regulated and overexpressed miRNAs extracted from Fig. 4 between noncancer donors and each cancer donor.

Extracted miRNAs were the second smallest logarithmic signal intensities in one group larger than the three pulsing second largest logarithmic signal intensities in the other group. The symbols − and + show noncancer and cancer donors, respectively. Pink lines highlight minimums in one group that were larger than the three pulsing maximums in the other group, giving highlighted miRNAs an edge over other miRNAs. Green and orange lines highlight cancer-specific down-regulated miRNAs and overexpressed miRNAs, respectively.

Table 2. Potential cancer-related urinary miRNAs as indicated in Fig. 5.

Blank spaces in the “Biological functions” column indicate that biological functions of the miRNAs have not been reported.

| Cancer types (down-regulation/overexpression) | miRNA names | Biological functions |

| Lung (down-regulation) | miR-3127-3p* | |

| miR-3130-5p* | ||

| miR-3131* | ||

| miR-3141* | ||

| miR-3150b-5p* | ||

| miR-3151-3p* | ||

| miR-3151-5p* | ||

| miR-3154* | ||

| miR-3160-3p* | ||

| miR-3160-5p* | ||

| miR-378a-5p | Suppressing cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis (52) |

|

| miR-520c-3p | Tumor suppressor (53–57) | |

| miR-526b-3p | Tumor suppressor (58) | |

| miR-3150a-3p | ||

| miR-3162-5p | ||

| miR-4254 | ||

| Lung (overexpression) | miR-3117-5p* | |

| miR-3118* | ||

| miR-3121-3p* | ||

| miR-3121-5p* | ||

| miR-3126-5p* | ||

| miR-3128* | ||

| miR-3133* | ||

| miR-3134* | ||

| miR-3136-3p* | ||

| miR-3136-5p* | ||

| miR-3139* | ||

| miR-3142* | ||

| miR-3143* | ||

| miR-3145-3p* | ||

| miR-3163* | Inhibiting non–small cell lung cancer cell growth (59) |

|

| miR-3166* | ||

| miR-3167* | ||

| miR-16-1-3p | Repressing gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis (60) |

|

| miR-424-3p | Potential metastasis-related miRNAs (61) | |

| miR-519c-5p | ||

| miR-525-5p | ||

| miR-551b-5p | ||

| miR-558 | Promoting tumorigenesis (62) | |

| miR-921 | ||

| miR-942-3p | ||

| miR-3126-3p | ||

| miR-3127-5p | Reducing non–small cell lung cancer cell proliferation (63) | |

| miR-3129-5p | ||

| miR-3144-5p | ||

| miR-3150a-5p | ||

| miR-3152-5p | ||

| miR-3155a | ||

| miR-3157-3p | ||

| miR-3159 | ||

| miR-3165 | ||

| miR-3678-3p | ||

| miR-4321 | ||

| miR-4521 | Significantly up-regulated miRNA in cancer stem cells (64) |

|

| miR-4800-3p | ||

| miR-4999-5p | ||

| miR-5096 | ||

| miR-5187-5p | ||

| miR-6874-5p | ||

| Pancreatic (down-regulation) | miR-372-3p* | Tumor suppressor (65) |

| miR-378b* | ||

| miR-520b* | Inhibiting cellular migration and invasion (66) | |

| miR-1266-3p* | ||

| miR-3605-5p* | ||

| miR-3612* | ||

| miR-4645-3p* | ||

| miR-4694-3p* | ||

| miR-4752* | ||

| miR-6816-3p* | ||

| miR-8087* | ||

| let-7f-2-3p | ||

| miR-15a-3p | Inducing apoptosis in human cancer cell lines (67) | |

| miR-20a-3p | ||

| miR-33b-3p | ||

| miR-34c-5p | Tumor suppressor (68) | |

| miR-93-5p | ||

| miR-130a-5p | ||

| miR-135a-5p | Inhibiting tumor metastasis (69) | |

| miR-135b-5p | ||

| miR-185-5p | Tumor suppressor (70) | |

| miR-203a-3p | ||

| miR-302d-5p | ||

| miR-337-3p | Tumor suppressor (71) | |

| miR-378c | ||

| miR-422a | Down-regulated in colon cancer (72) | |

| miR-449c-5p | ||

| miR-483-5p | ||

| miR-506-3p | Inducing differentiation (73) | |

| miR-511-5p | ||

| miR-520c-3p | Tumor suppressor (53–57) | |

| miR-654-3p | ||

| miR-668-5p | ||

| miR-670-5p | ||

| miR-671-3p | ||

| miR-744-3p | ||

| miR-1178-3p | ||

| miR-1254 | ||

| miR-1284 | Down-regulated in lymph node metastatic sites (74) | |

| miR-1323 | Modulating radioresistance (75) | |

| miR-2116-5p | ||

| miR-2355-3p | ||

| miR-3132 | ||

| miR-3138 | ||

| miR-3164 | ||

| miR-3186-3p | ||

| miR-3189-3p | ||

| miR-3198 | ||

| miR-3200-5p | ||

| miR-3657 | ||

| miR-3667-5p | ||

| miR-3680-5p | ||

| miR-3692-5p | ||

| miR-3713 | ||

| miR-3921 | ||

| miR-3936 | ||

| miR-4273 | Increasing colorectal cancer risk (76) | |

| miR-4299 | ||

| miR-4306 | ||

| miR-4316 | ||

| miR-4319 | ||

| miR-4421 | ||

| miR-4429 | ||

| miR-4435 | ||

| miR-4441 | ||

| miR-4473 | ||

| miR-4506 | ||

| miR-4633-5p | ||

| miR-4658 | ||

| miR-4733-5p | ||

| miR-4733-3p | ||

| miR-5004-3p | ||

| miR-5194 | ||

| miR-5197-5p | ||

| miR-5571-5p | ||

| miR-6083 | ||

| miR-6717-5p | ||

| miR-6720-5p | ||

| miR-6767-3p | ||

| miR-6781-3p | ||

| miR-6811-3p | ||

| miR-6821-3p | ||

| miR-6828-5p | ||

| miR-6832-5p | ||

| miR-6837-3p | ||

| miR-6841-5p | ||

| miR-6853-5p | ||

| miR-6871-3p | ||

| miR-6875-5p | ||

| miR-6878-5p | ||

| miR-7112-3p | ||

| miR-7703 | ||

| miR-7848-3p | ||

| miR-7856-5p | ||

| Pancreatic (overexpression) | let-7i-3p | |

| miR-183-5p | Promoting cancer proliferation, invasion, and metastasis (77) |

|

| miR-202-5p | Increasing TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 protein expressions (78) | |

| miR-409-5p | Promoting tumorigenesis (79) | |

| miR-4661-5p | ||

| miR-4800-3p | ||

| miR-5587-5p | ||

| Liver (down-regulation) | let-7i-2-3p | |

| miR-520c-3p | Tumor suppressor (53–57) | |

| Liver (overexpression) | miR-4521* | |

| let-7c-3p | ||

| let-7i-5p | ||

| miR-16-1-3p | Repressing gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis (60) | |

| miR-26a-1-3p | ||

| miR-28-5p | Suppressing insulin-like growth factor 1 expression (80) | |

| miR-105-5p | ||

| miR-195-3p | ||

| miR-200b-5p | ||

| miR-219a-2-3p | ||

| miR-297 | Promoting cell proliferation and invasion (81) | |

| miR-300 | Inhibiting pituitary tumor transforming gene expression (82) |

|

| miR-330-3p | Promoting invasion and metastasis (83) | |

| miR-374b-5p | ||

| miR-431-5p | ||

| miR-454-5p | Promoting tumorigenesis (84) | |

| miR-513c-5p | ||

| miR-548ax | ||

| miR-593-5p | ||

| miR-623 | ||

| miR-664a-5p | ||

| miR-942-3p | ||

| miR-1205 | ||

| miR-1276 | ||

| miR-1288-3p | ||

| miR-1297 | Promoting cell proliferation (85) | |

| miR-3678-3p | ||

| miR-4283 | ||

| miR-4295 | Promoting cell proliferation and invasion (86) | |

| miR-4439 | ||

| miR-4524b-5p | ||

| miR-4703-3p | ||

| miR-4768-5p | ||

| miR-4800-3p | ||

| miR-5187-5p | ||

| miR-5696 | ||

| miR-7161-5p | ||

| Bladder (down-regulation) | let-7f-2-3p | |

| miR-520c-3p | Tumor suppressor (53–57) | |

| miR-4783-5p | ||

| Bladder (overexpression) | miR-16-1-3p | Repressing gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis (60) |

| miR-23b-3p | Regulating chemoresistance of gastric cancer cell (87) | |

| miR-28-5p | Suppressing insulin-like growth factor 1 expression (80) | |

| miR-92a-2-5p | ||

| miR-142-3p | Promoting malignant phenotypes (88) | |

| miR-195-3p | Promoting tumorigenesis and inhibiting apoptosis (89) | |

| miR-196b-5p | ||

| miR-299-3p | Reducing Oct4 gene expression (90) | |

| miR-492 | ||

| miR-513b-5p | ||

| miR-601 | ||

| miR-619-5p | ||

| miR-1285-3p | ||

| miR-3155a | ||

| miR-3162-5p | ||

| miR-3678-3p | ||

| miR-4283 | ||

| miR-4295 | Promoting bladder cancer cell proliferation (91) | |

| miR-4311 | ||

| miR-4531 | ||

| miR-5096 | ||

| miR-5187-5p | ||

| Prostate (down-regulation) | miR-15a-3p | Inducing apoptosis in human cancer cell lines (67) |

| miR-135b-5p | ||

| miR-520c-3p | Tumor suppressor (53–57) | |

| miR-4783-5p | ||

| miR-7849-3p | ||

| Prostate (overexpression) | miR-4531* | |

| miR-28-5p | Suppressing insulin-like growth factor 1 expression (80) | |

| miR-103a-2-5p | ||

| miR-105-5p | Inhibiting the expression of tumor-suppressive genes (92) | |

| miR-124-3p | Regulating cell proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis (93) | |

| miR-151a-5p | Tumor cell migration and invasion (94) | |

| miR-151b | ||

| miR-200a-5p | ||

| miR-300 | Promoting cell proliferation and invasion (95) | |

| miR-424-3p | ||

| miR-519c-5p | ||

| miR-551b-5p | ||

| miR-617 | ||

| miR-873-3p | ||

| miR-921 | ||

| miR-1288-3p | ||

| miR-3124-5p | ||

| miR-3155a | ||

| miR-3917 | ||

| miR-4283 | ||

| miR-4727-3p | ||

| miR-5096 | ||

| miR-5187-5p | ||

| miR-6074 | ||

| miR-6874-5p | ||

| miR-6892-5p |

*Marks showing miRNAs highlighted by pink lines in Fig. 5.

Although we need to make more trials for clear recognition of statistically significant down-regulated and overexpressed miRNAs (51) based on comparisons with published results (52–95), we can say that the device mainly unveils two types of miRNA groups: miRNAs with unreported biological functions and miRNAs with previously reported biological functions. In addition, the former can be divided into two subgroups: potential cancer-related miRNAs and artifacts presumably derived from EV-free miRNAs. The latter also has two subgroups: miRNAs with functions that positively correlate with disease outcomes, such as miR-520c-3p (tumor suppressor, down-regulated miRNAs in urine from all cancer patients) (53–57), and miRNAs with a counterintuitive function-disease relationship, such as miR-16-1-3p (repressing gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis, overexpressed miRNAs in urine from liver and bladder cancer patients) (60). For the counterintuitive case, three possibilities were considered: The first possibility was that patients had potentially corresponding risks; the second possibility was that current studies about a correlation between miRNA functions and disease risks could not cover a relationship between the miRNAs concerned and cancer types; and the third possibility was that the miRNAs were also referable to artifacts. Complete medical checkups before urine sampling, further studies about the correlation, and more trials will offer answers for these possibilities. We also compared the overexpressed miRNAs with previously reported urinary miRNAs (shown as cell-free and exosome-derived top 25 up-regulated miRNAs) (96), which were extracted using a commercially available kit from 4 ml of urine from bladder cancer patients, and concluded that 20 miRNAs, such as miR-4454, were found in our results (data S1); however, these miRNAs were not identified as candidates for a cancer indicator. This is because we could also find the miRNAs in the results for noncancer subjects, and we could not find any significant difference in logarithmic fluorescence intensity between samples from noncancer subjects and bladder cancer patients for the miRNAs. More trials would allow us to decide whether these miRNAs can be identified as candidates and whether the remaining five miRNAs can be found (to show a statistically significant difference with 95% reliability and 5% sampling error for a population size of more than 1 million, we need to conduct 384 trails).

DISCUSSION

To summarize, we have demonstrated that our nanowire-anchored microfluidic device, which had bonding of the nanowire-embedded PDMS and the microfluidic herringbone-structured PDMS substrates, could achieve higher efficiency for in situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs compared to the most popular conventional method of ultracentrifugation. Surprisingly, the device could extract a much larger variety of species of miRNAs than ultracentrifugation despite the fact that the device uses a smaller sample volume and shorter treatment time than the latter method. The positively charged surface nanowires played an important role in the highly efficient EV collection, and the mechanical stability of nanowires anchored into PDMS during lysis buffer flow had an important impact on in situ extraction of miRNAs. We could find cancer-related miRNAs from urine samples of just 1 ml for not only urologic malignancies but also nonurologic ones. Although we need to perform further trials for biomarker recognition, the present results have led us to believe that our developed approach will be a powerful tool that offers a new strategy for researchers to discover cancer-related miRNAs in urine samples for future medical applications and to perform urinary miRNA-based diagnosis for timely medical checkups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fabrication procedure for nanowires anchored into PDMS

After cleaning the Si (100) substrates (Advantech Co. Ltd.) (fig. S1A), positive photoresist (OFPR8600, Tokyo Ohka Kogyo Co. Ltd.) was coated on the Si substrates, and then the channel pattern was formed by photolithography (fig. S1B). A 140-nm-thick Cr layer was deposited on the substrate by sputtering (fig. S1B). After removal of the photoresist (fig. S1D), the Cr layer was thermally oxidized at 400°C for 2 hours; the thermally oxidized Cr layer was a seed layer for ZnO nanowire growth. The ZnO nanowires were grown by immersing the substrate in a solution mixture of 15 mM hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA; Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.) and 15 mM zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) at 95°C for 3 hours (fig. S1E). The nanowires grown on the substrate were cleaned using Millipore water and allowed to air-dry overnight in a vacuum desiccator. Then, PDMS (Silpot 184, Dow Corning Corp.) was poured onto the nanowire-grown substrate, followed by curing (fig. S1F). After peeling off the PDMS from the substrate, the nanowires were transferred to the PDMS from the substrate (fig. S1G). The transferred nanowires were uniformly and deeply buried into PDMS with their heads slightly emerged (fig. S1H), and the heads provided growth points for the second nanowire growth. The second nanowire growth was carried out by immersing the PDMS in the mixed solution of 15 mM HMTA and 15 mM zinc nitrate hexahydrate at 95°C for 3 hours (fig. S1I). After the nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate was cleaned using Millipore water and allowed to air-dry overnight in the vacuum desiccator, we measured nanowire diameters and spacing between nanowires using FESEM (SUPRA 40VP, Carl Zeiss).

Nanowire-anchored microfluidic device for in situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs

A nanowire-anchored microfluidic device for in situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs was fabricated by bonding the nanowire-embedded PDMS substrate and a herringbone-structured PDMS substrate. The herringbone-structured PDMS substrate had a microchannel (width, 2 mm; length, 2 cm; and height, 50 μm) with a 12-μm-high herringbone structure. The surfaces of the nanowire-embedded PDMS and the herringbone-structured PDMS substrates were treated using a plasma etching apparatus (Meiwafosis Co. Ltd.) and then bonded. This bonded device was heated at 180°C for 3 min to achieve strong bonding (fig. S1J). Next, the herringbone-structured PDMS was connected to PEEK tubes [0.5 mm (outside diameter) × 0.26 mm (inside diameter); length, 10 cm; Institute of Microchemical Technology Co. Ltd.] for an inlet and an outlet. The microfluidic herringbone structure contributed to the increase of collection efficiency (fig. S10).

EDS elemental mappings of cross-sectional FESEM images

Elemental mappings of PDMS without nanowires, PDMS with buried nanowires, and PDMS-anchored ZnO nanowires were obtained by FESEM (JSM-7610F, Jeol) equipped with the EDS function. We used accelerating voltage conditions of 5 and 30 kV for the top-view images and the cross-sectional images, respectively. The images were 512 × 384 pixels and the delay time for each pixel was 0.1 ms. The images were integrated for 100 cycles. The peaks of Si Kα (1.739 keV) and Zn Lα (1.012 keV) were chosen to construct the elemental mapping images. Elemental mapping of ZnO/Al2O3 core-shell nanowires was also performed by FESEM equipped with the EDS function at an accelerating voltage condition of 30 kV. For preparation of a scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM) specimen, we first cut off the nanowires from the substrate using an ordinary cutting blade, and then they were collected and transferred onto the TEM grid (Cu mesh with carbon microgrid; Jeol) by the contact printing technique. The STEM images were 512 × 384 pixels and the delay time for each pixel was 0.1 ms. The images were integrated for 100 cycles. The peaks of Zn Kα (8.630 keV), O Kα (0.525 keV), and Al Kα (1.486 keV) were chosen to construct the elemental mapping images.

In situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs using the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device

Commercially available urine (single donor human urine; Innovative Research Inc.) was centrifuged (15 min, 4°C, 3000g) to remove apoptotic bodies (5) before use. Then, a 1-ml urine sample aliquot was introduced into the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device at a flow rate of 50 μl/min using a syringe pump (KDS-200, KD Scientific Inc.). The miRNA extraction from the collected EVs on nanowires was performed using Cell Lysis Buffer M [20 mM tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mM sodium chloride, 2.5 mM magnesium chloride, and 0.05 w/v% NP-40 substitute; Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.] introduced at a flow rate of 50 μl/min by the syringe pump. We used the same lysis buffer at a flow rate of 50 μl/min for the experiment to study peeling-off of the nanowires (Fig. 1, I to K, and fig. S4).

EV collection followed by miRNA extraction in urine using ultracentrifugation

Commercially available urine (single donor human urine) was centrifuged (15 min, 4°C, 3000g) to remove apoptotic bodies (5), and then the urine was centrifuged (15 min, 4°C, 12,000g) to remove cellular debris (29) before use. Next, a 20-ml urine sample was ultracentrifuged (2 hours, 4°C, 110,000g) (29). After discarding the supernatant, we added 20 ml of 0.22-μm filtered phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) to the collected EVs, and this was ultracentrifuged again (70 min, 4°C, 110,000g) (29). After discarding the supernatant, we added 20 ml of 0.22-μm filtered PBS to the collected EVs, and the sample was ultracentrifuged for a third time (70 min, 4°C, 110,000g) (29). Finally, we discarded the supernatant and applied the lysis buffer to extract the miRNAs.

EV collection followed by miRNA extraction in urine using a commercially available kit

Commercially available urine (single donor human urine) was centrifuged (15 min, 4°C, 3000g) to remove apoptotic bodies (5) before use. The EVs were collected from a 1-ml urine sample according to the kit (ExoQuick-TC, System Biosciences Inc.) manufacturer’s instruction manual. Finally, we applied the lysis buffer to extract the miRNAs.

Microarray analysis of miRNA expression

We used Toray’s 3D-Gene (Toray Industries) human miRNA chips for miRNA expression profiling. The miRNA solution extracted by lysis buffer was purified using the SeraMir Exosome RNA Purification Column Kit (System Biosciences Inc.) according to the kit manufacturer’s instruction manual. Fifteen microliters of purified miRNA was analyzed for miRNA profiling using a microarray and the 3D-Gene Human miRNA Oligo chip ver.21 (Toray Industries). Microarray analysis of miRNA expression containing 2565 human miRNA probes showed that each signal intensity corresponded to one miRNA type. The expression level of each miRNA was expressed as the background-subtracted signal intensity of all the miRNAs in each microarray. For a comparison of miRNA expression level between the same urine miRNA samples extracted by nanowires and ultracentrifugation or a commercially available kit, signal intensity was globally normalized. We made a scatterplot of globally normalized intensities greater than or equal to 10 (nanowires versus ultracentrifugation or kit). Each point shows normalized intensities when using nanowires and ultracentrifugation or kit for the same miRNA type. For a comparison of miRNA expression between the same urine miRNA samples extracted by nanowires and ultracentrifugation or kit, signal intensities were log2-transformed. For a comparison of miRNA expression between cancer and noncancer donor urine samples, globally normalized intensities for each sample were log2-transformed. The normalized intensities were colored black (intensity = 5), blue (intensity ≤ 2), and yellow (intensity ≥ 8) for the heat maps.

EV zeta potential

After the ultracentrifugation process, EV zeta potential was measured using a dynamic light-scattering apparatus (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments Ltd.).

Size distribution and concentrations of the urinary free-floating objects

Size distribution and concentration of the urinary free-floating objects were measured using a nanoparticle analyzing system (NanoSight, Malvern Instruments Ltd.); the concentrations of the urinary free-floating objects with diameters of up to 200 nm in the untreated urine, in the flow-through fraction of the urine being processed by the device, and in the ultracentrifuged urine were 2.6 × 1012, 5.8 × 109, and 3.5 × 109 ml−1, respectively. Size distribution and concentration of the urinary free-floating objects were also measured using a nanoparticle detector (qNano, Meiwafosis Co. Ltd.) with a 100-nm nanopore membrane (NP100, Meiwafosis Co. Ltd.); the concentrations of the urinary free-floating objects in the untreated urine, in the flow-through fraction of the urine being processed by the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device, and in the ultracentrifuged urine were 1.4 × 1012, 2.4 × 1010, and 2.5 × 1010 ml−1, respectively.

Fluorescent molecule labeling of EVs

We labeled EVs using fluorescent molecules of PKH26 (excitation/emission = 551/567 nm; Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC), which could penetrate into the lipid bilayers of the EVs. We added 5 μg of PKH26 for 1.5 × 108 ml−1 of EVs in 240 μl of 0.22-μm filtered Millipore water. The PKH26-labeled EVs were introduced into a device with nanowires at a flow rate of 10 μl/min using the syringe pump and then Millipore water was introduced into the device at the same flow rate to remove uncollected EVs. Finally, we observed the fluorescence of EVs using a fluorescence microscope (AZ100, Nikon Corp.). After that, we peeled off the device and observed the EV-collected nanowires using FESEM (SUPRA 40VP, Carl Zeiss).

Membrane protein detection

After introduction of EVs, PBS was introduced into a device with nanowires to remove uncollected EVs. Then, we introduced 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories Inc.) into the device and let it stand for 15 min. After washing out the device using PBS, we introduced a mouse monoclonal anti-human Alexa Fluor 488–labeled CD63 antibody (10 μg/ml; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) or a mouse monoclonal anti-human CD81 antibody (10 μg/ml; Abcam PLC) into the device and then let the antibody solution stand for 15 min. In addition, for CD81 detection, we washed out the device using PBS, introduced a goat polyclonal anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488–labeled immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody (5 μg/ml; Abcam PLC) into the device, and then let the secondary antibody solution stand for 15 min. Finally, we washed out the device using PBS and followed that with fluorescence intensity observation under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Co. Ltd.). To obtain the background value, we used PBS instead of the EV sample. Regarding detection using a 96-well plate (Nunc Co. Ltd.), we injected the EV samples into the plate wells and let them stand for 6 hours, and then we discarded the samples. After washing out the plate using PBS, we applied 1% BSA solution to the plate wells, let it stand for 90 min, and then discarded it. Again, we washed out the plate using PBS, applied the mouse monoclonal anti-human Alexa Fluor 488–labeled CD63 antibody (10 μg/ml) or the mouse monoclonal anti-human CD81 antibody (10 μg/ml) into the plate wells, and let them stand for 45 min. In addition, for CD81 detection, we washed out the device using PBS, applied the goat polyclonal anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488–labeled IgG secondary antibody (5 μg/ml) into the plate, and let it stand for 45 min. Finally, we washed out the device using PBS followed by fluorescence intensity observation using a plate reader (POLARstar OPTIMA, BMG Labtech Japan Ltd.). To obtain the background value, we used PBS instead of the EV sample.

Fabrication of ZnO/Al2O3 core-shell nanowires

After fabrication of ZnO nanowires, we covered the nanowires using an atomic layer deposition apparatus (Savannah G2, Ultratech Inc.). For Al2O3 deposition, we used trimethylaluminum and H2O precursors at 150°C for 100 cycles.

Urine sample information and in situ extraction of urine EV–encapsulated miRNAs using the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device

The following urine samples (BioreclamationIVT) were used: noncancer urine (ages 53, 60, and 50), lung cancer urine (age 68, stage 2b; age 54, stage 3a; and age 50, stage 3b), pancreatic cancer urine (age 56, stage 2a; age 61, stage 2a; and age 74, stage 3), liver cancer urine (age 49, stage 3; age 64, stage 3a; and age 18, stage 3c), bladder cancer urine (age 63, stage 1; age 65, stage 1; and age 67, stage 0a), and prostate cancer urine (age 58, stage 4; age 57, stage 2a; and 54; stage 2b). These urine samples were centrifuged (15 min, 4°C, 3000g) to remove apoptotic bodies (5) before use. Then, a 1-ml urine sample aliquot was introduced into the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device at a flow rate of 50 μl/min using the syringe pump. The miRNA extraction from the collected EVs on the nanowires was performed with the lysis buffer introduced at a flow rate of 50 μl/min using the syringe pump.

Identifying urinary miRNAs that could potentially serve as biomarkers for cancer

According to the Z-score of 1.96 (95% reliability and 5% significance level) and the relationship of coefficient of variation (CV) (without concrete numerical values) versus log2(intensity) provided by Toray, the 95% confidence interval could be calculated using (average) ± 1.96 × (average × CV/100). When we used X% for CV in the relationship log2(intensity) = 3, the upper limit of the confidence interval was 8 + 0.16X. The CV value in log2(intensity) = 5 and 6 seemed to be 0.7X and 0.5X% from the relationship, and the lower limits of the confidence interval were 32 − 0.44X and 64 − 0.63X, respectively. Considering the 5% significance level, we found that the CVs for each case were less than 40 and 71%. We did not consider the CV value of more than 70% to be reasonable, and we set a difference of three logarithmic intensities for the statistically significant threshold in Fig. 5.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by PRESTO (JPMJPR151B); the Japan Science and Technology Agency; the “Development of Diagnostic Technology for Detection of miRNA in Body Fluids” grant from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development and New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization; the ImPACT Program of the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (Cabinet Office, Government of Japan); the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) 16H02091; the Nanotechnology Platform Program (Molecule and Material Synthesis) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT); and the Cooperative Research Program of “Network Joint Research Center for Materials and Devices.” Author contributions: T. Yasui, T. Yanagida, N.K., H.Y., T.O., T.K., and Y.B. planned and designed the experiments. T. Yasui, T. Yanagida, S.I., Y.K., D.T., T.N., K.N., T.S., N.K., Y.H., S.R., and M.K. fabricated the experimental setups. T. Yasui, S.I., Y.K., D.T., T.N., Y.N., and I.A.T. performed EV collection using nanowires and data analyses. T. Yasui, T. Yanagida, K.N., and N.K. wrote the paper. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/3/12/e1701133/DC1

fig. S1. Schematic of the fabrication procedure for nanowires anchored into PDMS.

fig. S2. Nanowires anchored into PDMS.

fig. S3. FESEM images and EDS elemental mappings corresponding to FESEM images for PDMS without nanowires, PDMS with buried nanowires, and nanowire-embedded PDMS; scale bars, 1 μm.

fig. S4. Mechanical stability of anchored nanowires and nonanchored nanowires.

fig. S5. Extraction process of miRNAs in urine using the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device, ultracentrifugation, and commercially available kits.

fig. S6. FESEM images and EDS elemental mappings of an STEM image of a single nanowire.

fig. S7. Detection of EVs on ZnO nanowires, ZnO/Al2O3 core-shell nanowires, and no nanowires using an antibody of CD9.

fig. S8. Zeta potential of EVs in urine.

fig. S9. Size distribution of EVs collected by ultracentrifugation and EV-free miRNAs collected onto nanowires.

fig. S10. Size distribution of the urinary free-floating objects.

movie S1. EV collection followed by miRNA extraction in urine using the nanowire-anchored microfluidic device.

data S1. Logarithmic signal intensities in noncancer miRNAs with those in cancer miRNAs.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Raposo G., Stoorvogel W., Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 200, 373–383 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans-Osses I., Reichembach L. H., Ramirez M. I., Exosomes or microvesicles? Two kinds of extracellular vesicles with different routes to modify protozoan-host cell interaction. Parasitol. Res. 114, 3567–3575 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma P., Pan Y., Li W., Sun C., Liu J., Xu T., Shu Y., Extracellular vesicles-mediated noncoding RNAs transfer in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 10, 57 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szatanek R., Baran J., Siedlar M., Baj-Krzyworzeka M., Isolation of extracellular vesicles: Determining the correct approach (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 36, 11–17 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeppesen D. K., Hvam M. L., Primdahl-Bengtson B., Boysen A. T., Whitehead B., Dyrskjøt L., Ørntoft T. F., Howard K. A., Ostenfeld M. S., Comparative analysis of discrete exosome fractions obtained by differential centrifugation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 3, 25011 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber J. A., Baxter D. H., Zhang S., Huang D. Y., Huang K. H., Lee M. J., Galas D. J., Wang K., The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin. Chem. 56, 1733–1741 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lv L.-L., Cao Y., Liu D., Xu M., Liu H., Tang R.-N., Ma K.-L., Liu B.-C., Isolation and quantification of microRNAs from urinary exosomes/microvesicles for biomarker discovery. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 9, 1021–1031 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez M. L., Khosroheidari M., Ravi R. K., DiStefano J. K., Comparison of protein, microRNA, and mRNA yields using different methods of urinary exosome isolation for the discovery of kidney disease biomarkers. Kidney Int. 82, 1024–1032 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J., Li S., Li L., Li M., Guo C., Yao J., Mi S., Exosome and exosomal microRNA: Trafficking, sorting, and function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 13, 17–24 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosaka N., Iguchi H., Ochiya T., Circulating microRNA in body fluid: A new potential biomarker for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Cancer Sci. 101, 2087–2092 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iero M., Valenti R., Huber V., Filipazzi P., Parmiani G., Fais S., Rivoltini L., Tumour-released exosomes and their implications in cancer immunity. Cell Death Differ. 15, 80–88 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor D. D., Gercel-Taylor C., MicroRNA signatures of tumor-derived exosomes as diagnostic biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 110, 13–21 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Nedawi K., Meehan B., Micallef J., Lhotak V., May L., Guha A., Rak J., Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 619–624 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshioka Y., Kosaka N., Konishi Y., Ohta H., Okamoto H., Sonoda H., Nonaka R., Yamamoto H., Ishii H., Mori M., Furuta K., Nakajima T., Hayashi H., Sugisaki H., Higashimoto H., Kato T., Takeshita F., Ochiya T., Ultra-sensitive liquid biopsy of circulating extracellular vesicles using ExoScreen. Nat. Commun. 5, 3591 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peinado H., Alečković M., Lavotshkin S., Matei I., Costa-Silva B., Moreno-Bueno G., Hergueta-Redondo M., Williams C., García-Santos G., Ghajar C. M., Nitadori-Hoshino A., Hoffman C., Badal K., Garcia B. A., Callahan M. K., Yuan J., Martins V. R., Skog J., Kaplan R. N., Brady M. S., Wolchok J. D., Chapman P. B., Kang Y., Bromberg J., Lyden D., Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat. Med. 18, 883–891 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C. Y., Hogan M. C., Ward C. J., Purification of exosome-like vesicles from urine. Methods Enzymol. 524, 225–241 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webber J., Steadman R., Mason M. D., Tabi Z., Clayton A., Cancer exosomes trigger fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Cancer Res. 70, 9621–9630 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skog J., Würdinger T., van Rijn S., Meijer D. H., Gainche L., Curry W. T. Jr, Carter B. S., Krichevsky A. M., Breakefield X. O., Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1470–1476 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlassov A. V., Magdaleno S., Setterquist R., Conrad R., Exosomes: Current knowledge of their composition, biological functions, and diagnostic and therapeutic potentials. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1820, 940–948 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnaud C. H., Seeking tiny vesicles for diagnostics. Chem. Eng. News 93, 30–32 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirschner M. B., Edelman J. J. B., Kao S. C.-H., Vallely M. P., van Zandwijk N., Reid G., The impact of hemolysis on cell-free microRNA biomarkers. Front. Genet. 4, 94 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor D. D., Zacharias W., Gercel-Taylor C., Exosome isolation for proteomic analyses and RNA profiling. Methods Mol. Biol. 728, 235–246 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeong S., Park J., Pathania D., Castro C. M., Weissleder R., Lee H., Integrated magneto–electrochemical sensor for exosome analysis. ACS Nano 10, 1802–1809 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sunkara V., Woo H.-K., Cho Y.-K., Emerging techniques in the isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles and their roles in cancer diagnostics and prognostics. Analyst 141, 371–381 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang P., He M., Zeng Y., Ultrasensitive microfluidic analysis of circulating exosomes using a nanostructured graphene oxide/polydopamine coating. Lab Chip 16, 3033–3042 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wunsch B. H., Smith J. T., Gifford S. M., Wang C., Brink M., Bruce R. L., Austin R. H., Stolovitzky G., Astier Y., Nanoscale lateral displacement arrays for the separation of exosomes and colloids down to 20 nm. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 936–940 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woo H.-K., Sunkara V., Park J., Kim T.-H., Han J.-R., Kim C.-J., Choi H.-I., Kim Y.-K., Cho Y.-K., Exodisc for rapid, size-selective, and efficient isolation and analysis of nanoscale extracellular vesicles from biological samples. ACS Nano 11, 1360–1370 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barutta F., Tricarico M., Corbelli A., Annaratone L., Pinach S., Grimaldi S., Bruno G., Cimino D., Taverna D., Deregibus M. C., Rastaldi M. P., Perin P. C., Gruden G., Urinary exosomal microRNAs in incipient diabetic nephropathy. PLOS ONE 8, e73798 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Théry C., Amigorena S., Raposo G., Clayton A., Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. Chapter 3, Unit 3.22 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petersen K. E., Manangon E., Hood J. L., Wickline S. A., Fernandez D. P., Johnson W. P., Gale B. K., A review of exosome separation techniques and characterization of B16-F10 mouse melanoma exosomes with AF4-UV-MALS-DLS-TEM. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 406, 7855–7866 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng L., Sun X., Scicluna B. J., Coleman B. M., Hill A. F., Characterization and deep sequencing analysis of exosomal and non-exosomal miRNA in human urine. Kidney Int. 86, 433–444 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duan X., Gao R., Xie P., Cohen-Karni T., Qing Q., Choe H. S., Tian B., Jiang X., Lieber C. M., Intracellular recordings of action potentials by an extracellular nanoscale field-effect transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 174–179 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan R., Park J.-H., Choi Y., Heo C.-J., Yang S.-M., Lee L. P., Yang P., Nanowire-based single-cell endoscopy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 191–196 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasui T., Rahong S., Motoyama K., Yanagida T., Wu Q., Kaji N., Kanai M., Doi K., Nagashima K., Tokeshi M., Taniguchi M., Kawano S., Kawai T., Baba Y., DNA manipulation and separation in sublithographic-scale nanowire array. ACS Nano 7, 3029–3035 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.So H., Lee K., Murthy N., Pisano A. P., All-in-one nanowire-decorated multifunctional membrane for rapid cell lysis and direct DNA isolation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 20693–20699 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu J., Fu T.-M., Cheng Z., Hong G., Zhou T., Jin L., Duvvuri M., Jiang Z., Kruskal P., Xie C., Suo Z., Fang Y., Lieber C. M., Syringe-injectable electronics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 629–636 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen Q., Xu L., Zhao L., Wu D., Fan Y., Zhou Y., OuYang W.-H., Xu X., Zhang Z., Song M., Lee T., Garcia M. A., Xiong B., Hou S., Tseng H.-R., Fang X., Specific capture and release of circulating tumor cells using aptamer-modified nanosubstrates. Adv. Mater. 25, 2368–2373 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J., Hong J. W., Kim D. P., Shin J. H., Park I., Nanowire-integrated microfluidic devices for facile and reagent-free mechanical cell lysis. Lab Chip 12, 2914–2921 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahong S., Yasui T., Kaji N., Baba Y., Recent developments in nanowires for bio-applications from molecular to cellular levels. Lab Chip 16, 1126–1138 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang S., Shen Y., Fang H., Xu S., Song J., Wang Z. L., Growth and replication of ordered ZnO nanowire arrays on general flexible substrates. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 10606–10610 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stroock A. D., Dertinger S. K. W., Ajdari A., Mezić I., Stone H. A., Whitesides G. M., Chaotic mixer for microchannels. Science 295, 647–651 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao D., Ohlendorf J., Chen Y., Taylor D. D., Rai S. N., Waigel S., Zacharias W., Hao H., McMasters K. M., Identifying mRNA, microRNA and protein profiles of melanoma exosomes. PLOS ONE 7, e46874 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi D.-S., Choi D.-Y., Hong B. S., Jang S. C., Kim D.-K., Lee J., Kim Y.-K., Kim K. P., Gho Y. S., Quantitative proteomics of extracellular vesicles derived from human primary and metastatic colorectal cancer cells. J. Extracell. Vesicles 1, 18704 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edgar J. R., Q&A: What are exosomes, exactly? BMC Biol. 14, 46 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elam J. W., George S. M., Growth of ZnO/Al2O3 alloy films using atomic layer deposition techniques. Chem. Mater. 15, 1020–1028 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu B., Hu R., Deng J., Studies on a potentiometric urea biosensor based on an ammonia electrode and urease: Immobilized on a γ-aluminum oxide matrix. Anal. Chim. Acta 341, 161–169 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu S., Wang Z. L., One-dimensional ZnO nanostructures: Solution growth and functional properties. Nano Res. 4, 1013–1098 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zang J., Li C. M., Cui X., Wang J., Sun X., Dong H., Sun C. Q., Tailoring zinc oxide nanowires for high performance amperometric glucose sensor. Electroanalysis 19, 1008–1014 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deregibus M. C., Figliolini F., D’Antico S., Manzini P. M., Pasquino C., De Lena M., Tetta C., Brizzi M. F., Camussi G., Charge-based precipitation of extracellular vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Med. 38, 1359–1366 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schlappi T. S., McCalla S. E., Schoepp N. G., Ismagilov R. F., Flow-through capture and in situ amplification can enable rapid detection of a few single molecules of nucleic acids from several milliliters of solution. Anal. Chem. 88, 7647–7653 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanley J. A., McNeil B. J., The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143, 29–36 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z., Ma B., Ji X., Deng Y., Zhang T., Zhang X., Gao H., Sun H., Wu H., Chen X., Zhao R., MicroRNA-378-5p suppresses cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells by targeting BRAF. Cancer Cell Int. 15, 40 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miao H.-L., Lei C.-J., Qiu Z.-D., Liu Z.-K., Li R., Bao S.-T., Li M.-Y., MicroRNA-520c-3p inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and invasion through induction of cell apoptosis by targeting glypican-3. Hepatol. Res. 44, 338–348 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu S., Zhu Q., Zhang Y., Song W., Wilson M. J., Liu P., Dual-functions of miR-373 and miR-520c by differently regulating the activities of MMP2 and MMP9. J. Cell. Physiol. 230, 1862–1870 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazan-Mamczarz K., Zhao X. F., Dai B., Steinhardt J. J., Peroutka R. J., Berk K. L., Landon A. L., Sadowska M., Zhang Y., Lehrmann E., Becker K. G., Shaknovich R., Liu Z., Gartenhaus R. B., Down-regulation of eIF4GII by miR-520c-3p represses diffuse large B cell lymphoma development. PLOS Genet. 10, e1004105 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lei C.-J., Yao C., Li D.-K., Long Z.-X., Li Y., Tao D., Liou Y.-P., Zhang J.-Z., Liu N., Effect of co-transfection of miR-520c-3p and miR-132 on proliferation and apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma Huh7. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 9, 898–902 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mudduluru G., Ilm K., Fuchs S., Stein U., Epigenetic silencing of miR-520c leads to induced S100A4 expression and its mediated colorectal cancer progression. Oncotarget 8, 21081–21094 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang R., Zhao J., Xu J., Wang J., Jia J., miR-526b-3p functions as a tumor suppressor in colon cancer by regulating HIF-1α. Am. J. Transl. Res. 8, 2783–2789 (2016). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Su L., Han D., Wu J., Huo X., Skp2 regulates non-small cell lung cancer cell growth by Meg3 and miR-3163. Tumour Biol. 37, 3925–3931 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang T., Hou J., Li Z., Zheng Z., Wei J., Song D., Hu T., Wu Q., Yang J. Y., Cai J.-c., miR-15a-3p and miR-16-1-3p negatively regulate Twist1 to repress gastric cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 13, 122–134 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen Q.-y., Jiao D.-m., Yan L., Wu Y.-q., Hu H.-z., Song J., Yan J., Wu L.-j., Xu L.-q., Shi J.-g., Comprehensive gene and microRNA expression profiling reveals miR-206 inhibits MET in lung cancer metastasis. Mol. Biosyst. 11, 2290–2302 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng L., Jiao W., Song H., Qu H., Li D., Mei H., Chen Y., Yang F., Li H., Huang K., Tong Q., miRNA-558 promotes gastric cancer progression through attenuating Smad4-mediated repression of heparanase expression. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2382 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun Y., Chen C., Zhang P., Xie H., Hou L., Hui Z., Xu Y., Du Q., Zhou X., Su B., Gao W., Reduced miR-3127-5p expression promotes NSCLC proliferation/invasion and contributes to dasatinib sensitivity via the c-Abl/Ras/ERK pathway. Sci. Rep. 4, 6527 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fang Y., Xiang J., Chen Z., Gu X., Li Z., Tang F., Zhou Z., miRNA expression profile of colon cancer stem cells compared to non-stem cells using the SW1116 cell line. Oncol. Rep. 28, 2115–2124 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang X., Huang M., Kong L., Li Y., miR-372 suppresses tumour proliferation and invasion by targeting IGF2BP1 in renal cell carcinoma. Cell Prolif. 48, 593–599 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lu Y.-C., Cheng A.-J., Lee L.-Y., You G.-R., Li Y.-L., Chen H.-Y., Chang J. T., MiR-520b as a novel molecular target for suppressing stemness phenotype of head-neck cancer by inhibiting CD44. Sci. Rep. 7, 2042 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Druz A., Chen Y.-C., Guha R., Betenbaugh M., Martin S. E., Shiloach J., Large-scale screening identifies a novel microRNA, miR-15a-3p, which induces apoptosis in human cancer cell lines. RNA Biol. 10, 287–300 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu Z., Wu Y., Tian Y., Sun X., Liu J., Ren H., Liang C., Song L., Hu H., Wang L., Jiao B., Differential effects of miR-34c-3p and miR-34c-5p on the proliferation, apoptosis and invasion of glioma cells. Oncol. Lett. 6, 1447–1452 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheng Z., Liu F., Zhang H., Li X., Li Y., Li J., Liu F., Cao Y., Cao L., Li F., miR-135a inhibits tumor metastasis and angiogenesis by targeting FAK pathway. Oncotarget 8, 31153–31168 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu C., Li G., Ren S., Su Z., Wang Y., Tian Y., Liu Y., Qiu Y., miR-185-3p regulates the invasion and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma by targeting WNT2B in vitro. Oncol. Lett. 13, 2631–2636 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang R., Leng H., Huang J., Du Y., Wang Y., Zang W., Chen X., Zhao G., miR-337 regulates the proliferation and invasion in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by targeting HOXB7. Diagn. Pathol. 9, 171 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lu M., Zhou X., Zheng C.-G., Liu F.-J., Expression profiling of miR-96, miR-584 and miR-422a in colon cancer and their potential involvement in colon cancer pathogenesis. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 15, 2535–2542 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao Z., Ma X., Hsiao T.-H., Lin G., Kosti A., Yu X., Suresh U., Chen Y., Tomlinson G. E., Pertsemlidis A., Du L., A high-content morphological screen identifies novel microRNAs that regulate neuroblastoma cell differentiation. Oncotarget 5, 2499–2512 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen W., Tang Z., Sun Y., Zhang Y., Wang X., Shen Z., Liu F., Qin X., miRNA expression profile in primary gastric cancers and paired lymph node metastases indicates that miR-10a plays a role in metastasis from primary gastric cancer to lymph nodes. Exp. Ther. Med. 3, 351–356 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Y., Han W., Ni T.-T., Lu L., Huang M., Zhang Y., Cao H., Zhang H.-Q., Luo W., Li H., Knockdown of microRNA-1323 restores sensitivity to radiation by suppression of PRKDC activity in radiation-resistant lung cancer cells. Oncol. Rep. 33, 2821–2828 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee A. R., Park J., Jung K. J., Jee S. H., Kim-Yoon S. J., Genetic variation rs7930 in the miR-4273-5p target site is associated with a risk of colorectal cancer. Oncotargets Ther. 9, 6885–6895 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miao F., Zhu J., Chen Y., Tang N., Wang X., Li X., MicroRNA-183-5p promotes the proliferation, invasion and metastasis of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Oncol. Lett. 11, 134–140 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mody H. R., Hung S. W., Pathak R. K., Griffin J., Cruz-Monserrate Z., Govindarajan R., miR-202 diminishes TGFβ receptors and attenuates TGFβ1-induced EMT in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 15, 1029–1039 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Josson S., Gururajan M., Hu P., Shao C., Chu G. C.-Y., Zhau H. E., Liu C., Lao K., Lu C.-L., Lu Y.-T., Lichterman J., Nandana S., Li Q., Rogatko A., Berel D., Posadas E. M., Fazli L., Sareen D., Chung L. W. K., miR-409-3p/-5p promotes tumorigenesis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and bone metastasis of human prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 4636–4646 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shi X., Teng F., Down-regulated miR-28-5p in human hepatocellular carcinoma correlated with tumor proliferation and migration by targeting insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). Mol. Cell. Biochem. 408, 283–293 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sun Y., Zhao J., Yin X., Yuan X., Guo J., Bi J., miR-297 acts as an oncogene by targeting GPC5 in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Prolif. 49, 636–643 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liang H.-q., Wang R.-j., Diao C.-f., Li J.-w., Su J.-l., Zhang S., The PTTG1-targeting miRNAs miR-329, miR-300, miR-381, and miR-655 inhibit pituitary tumor cell tumorigenesis and are involved in a p53/PTTG1 regulation feedback loop. Oncotarget 6, 29413–29427 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mesci A., Huang X., Taeb S., Jahangiri S., Kim Y., Fokas E., Bruce J., Leong H. S., Liu S. K., Targeting of CCBE1 by miR-330-3p in human breast cancer promotes metastasis. Br. J. Cancer 116, 1350–1357 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yu L., Gong X., Sun L., Yao H., Lu B., Zhu L., miR-454 functions as an oncogene by inhibiting CHD5 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 6, 39225–39234 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu C., Wang C., Wang J., Huang H., miR-1297 promotes cell proliferation by inhibiting RB1 in liver cancer. Oncol. Lett. 12, 5177–5182 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shao M., Geng Y., Lu P., Xi Y., Wei S., Wang L., Fan Q., Ma W., miR-4295 promotes cell proliferation and invasion in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma via CDKN1A. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 464, 1309–1313 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.An Y., Zhang Z., Shang Y., Jiang X., Dong J., Yu P., Nie Y., Zhao Q., miR-23b-3p regulates the chemoresistance of gastric cancer cells by targeting ATG12 and HMGB2. Cell Death Dis. 6, e1766 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dickman C. T. D., Lawson J., Jabalee J., MacLellan S. A., LePard N. E., Bennewith K. L., Garnis C., Selective extracellular vesicle exclusion of miR-142-3p by oral cancer cells promotes both internal and extracellular malignant phenotypes. Oncotarget 8, 15252–15266 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jin L., Li X., Li Y., Zhang Z., He T., Hu J., Liu J., Chen M., Shi M., Jiang Z., Gui Y., Yang S., Mao X., Lai Y., Identification of miR-195-3p as an oncogene in RCC. Mol. Med. Rep. 15, 1916–1924 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Göhring A. R., Reuter S., Clement J. H., Cheng X., Theobald J., Wölfl S., Mrowka R., Human microRNA-299-3p decreases invasive behavior of cancer cells by downregulation of Oct4 expression and causes apoptosis. PLOS ONE 12, e0174912 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nan Y.-H., Wang J., Wang Y., Sun P.-H., Han Y.-P., Fan L., Wang K.-C., Shen F.-J., Wang W.-H., MiR-4295 promotes cell growth in bladder cancer by targeting BTG1. Am. J. Transl. Res. 9, 1960 (2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nabavi N., Saidy N. R. N., Venalainen E., Haegert A., Parolia A., Xue H., Wang Y., Wu R., Dong X., Collins C., Crea F., Wang Y., miR-100-5p inhibition induces apoptosis in dormant prostate cancer cells and prevents the emergence of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 4079 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Deng D., Wang L., Chen Y., Li B., Xue L., Shao N., Wang Q., Xia X., Yang Y., Zhi F., MicroRNA-124-3p regulates cell proliferation, invasion, apoptosis, and bioenergetics by targeting PIM1 in astrocytoma. Cancer Sci. 107, 899–907 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chiyomaru T., Yamamura S., Zaman M. S., Majid S., Deng G., Shahryari V., Saini S., Hirata H., Ueno K., Chang I., Tanaka Y., Tabatabai Z. L., Enokida H., Nakagawa M., Dahiya R., Genistein suppresses prostate cancer growth through inhibition of oncogenic microRNA-151. PLOS ONE 7, e43812 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xue Z., Zhao J., Niu L., An G., Guo Y., Ni L., Up-regulation of MiR-300 promotes proliferation and invasion of osteosarcoma by targeting BRD7. PLOS ONE 10, e0127682 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 96.Armstrong D. A., Green B. B., Seigne J. D., Schned A. R., Marsit C. J., MicroRNA molecular profiling from matched tumor and bio-fluids in bladder cancer. Mol. Cancer 14, 194 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials