Abstract

Background:

Household air pollution from solid fuel burning is a leading contributor to disease burden globally. Fine particulate matter () is thought to be responsible for many of these health impacts. A co-pollutant, carbon monoxide (CO) has been widely used as a surrogate measure of in studies of household air pollution.

Objective:

The goal was to evaluate the validity of exposure to CO as a surrogate of exposure to in studies of household air pollution and the consistency of the relationship across different study settings and conditions.

Methods:

We conducted a systematic review of studies with exposure and/or cooking area and CO measurements and assembled 2,048 and CO measurements from a subset of studies (18 cooking area studies and 9 personal exposure studies) retained in the systematic review. We conducted pooled multivariate analyses of associations, evaluating fuels, urbanicity, season, study, and CO methods as covariates and effect modifiers.

Results:

We retained 61 of 70 studies for review, representing 27 countries. Reported correlations (r) were lower for personal exposure (range: 0.22–0.97; ) than for cooking areas (range: 0.10–0.96; ). In the pooled analyses of personal exposure and cooking area concentrations, the variation in ln(CO) explained 13% and 48% of the variation in ln(), respectively.

Conclusions:

Our results suggest that exposure to CO is not a consistently valid surrogate measure of exposure to . Studies measuring CO exposure as a surrogate measure of PM exposure should conduct local validation studies for different stove/fuel types and seasons. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP767

Introduction

Over 2.8 billion people are exposed to household air pollution from cooking and heating with solid fuels, which include biomass (e.g., wood, crop residues, animal dung, charcoal) and coal (Bonjour et al. 2013). Household air pollution comprises many pollutants (Zhang and Smith 2007; Naeher et al. 2007) and is a leading health risk factor, annually responsible for an estimated 2.9 million premature deaths (GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators et al. 2015). Two widely studied air pollutants from solid fuel combustion are particulate matter (PM) and carbon monoxide (CO). Strong epidemiologic and experimental evidence point to the mass of PM with a diameter () as a pollutant that is causally associated with many health outcomes (Pope and Dockery 2006; U.S. EPA 2009) and is likely a strong driver of many health effects associated with household air pollution (Brook et al. 2010; WHO 2014). Evidence for adverse health outcomes related to low-to-moderate CO exposure is sparse and less consistent, with associations between infant low birth weight and women’s CO exposure during pregnancy demonstrated in some studies (Ritz and Yu 1999; Ha et al. 2001; Gouveia et al. 2004; Salam et al. 2005), but not in others (Alderman et al. 1987; Koren et al. 1991; Chen et al. 2002; Parker et al. 2005; Wylie et al 2016). In epidemiologic and exposure studies of household air pollution, including those evaluating maternal exposure and birth outcomes (Thompson et al. 2011; Dix-Cooper et al. 2012), CO exposure is usually measured as a surrogate of exposure (Balakrishnan et al. 2011; Clark et al. 2013).

Accurate exposure assessment is the basis for evaluating exposure–response relationships (Armstrong 1998, 2004), and in the context of household air pollution, critical to interpreting the effectiveness of stove-fuel interventions (Peel et al. 2015). Direct measurement of personal exposure to mass is considered the “gold standard” in epidemiologic studies (Smith 1993; Northcross et al. 2015), but is challenging to measure in large populations (Northcross et al. 2015) and in infants (Naeher et al. 2001; Dionisio et al. 2008). Questionnaires and cooking area have been used alone or in combination as surrogates but were poorly associated with personal exposure in validation studies (Ezzati et al. 2000; Bruce et al. 2004; Cynthia et al. 2008; Baumgartner et al. 2011; Ni et al. 2016). As an alternative, many health and intervention studies have measured personal exposure to CO as a surrogate for given that it is also a major component of household air pollution but is easier and less costly to measure than (Naeher et al. 2001; Dionisio et al. 2008; Smith et al. 2010).

The empirical evidence supporting the validity of personal CO exposure as a surrogate of personal exposure is limited and inconclusive, despite its common use. Direct measurements of personal and CO exposure were not correlated (Pearson ) in children living in homes cooking with wood in The Gambia (Dionisio et al. 2012) and were only moderately correlated in women in Peru (Spearman ; Commodore et al. 2013), Tanzania (Spearman ; Wylie et al. 2016), and China (Spearman ; Ni et al. 2016). In rural Guatemala, however, variation in personal CO exposures explained 78% of the variation in personal exposures among women (McCracken et al. 2013). It is not known whether the strength of a relationship in one setting is transportable to other settings. Here, we use definitions for a validation study and transportability adapted from Spiegelman (2010):

Validation study: a study in which data are simultaneously collected on the exposure surrogate (CO) and the gold standard method of exposure assessment (PM2.5). This study may be external to the main epidemiologic study, or be a subsample internal to the main study.

Transportability: the extent to which the relationship in a validation study is similar to the one that generates the surrogate exposure in the main study (PM2.5).

Studies in Bolivia, Peru, Ghana, Kenya, Mexico, South Africa, the Philippines, and Burkina Faso (Röllin et al. 2004; Saksena et al. 2007; Riojas-Rodriguez et al. 2011; Ochieng et al. 2013; Commodore et al. 2013; Alexander et al. 2014; Thorsson et al. 2014; Jack et al. 2015; Yip et al. 2017) measured CO exposure as a surrogate for without prior validation; one reason given was the strong exposure relationship observed in Guatemala (McCracken et al. 2013; Naeher et al. 2000a). Similarly, it is unknown whether the exposure relationship within a single study setting and population under one set of study conditions is transportable to other study conditions (e.g., pre- vs. postintervention; heating- vs. nonheating season) in the same setting and population, which is an approach taken in some studies (Smith-Sivertsen et al. 2009; Smith et al. 2011; Guarnieri et al. 2014; Pope et al. 2015). Finally, it is unclear whether the correlation in cooking areas can be extrapolated to personal exposures in the same setting, which several studies have done (Bruce et al. 2004; Northcross et al. 2010; Dionisio et al. 2012; Alnes et al. 2014). Of these, only one (Dionisio et al. 2012) directly compared actual versus predicted exposure, finding no relationship (Pearson ).

Both PM and CO are products of incomplete combustion and co-emitted during solid fuel burning. The amount and relative proportion of these pollutants emitted from stoves can vary by factors including fuel type and moisture content; combustion efficiency and power throughout burn cycles; stove ventilation; and the behavior of energy users (Roden et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2012; Jetter et al. 2012; Carter et al. 2014). For personal exposures, the presence of other community or regional air pollution sources with different pollutant composition (Huang et al. 2015) could further impact the strength and consistency of a personal PM-CO association.

We systematically reviewed the methods and correlation coefficients reported in studies with paired measurements of and CO personal exposures and/or cooking area concentrations in settings where biomass is the primary household fuel. We also obtained 2,048 paired and CO measurements from previously completed studies along with relevant information on season, level of urbanicity, fuel type, and other energy use behaviors to conduct pooled analyses of the relationship for personal exposures and cooking area concentrations. For the pooled analysis, our first objective was to evaluate the validity of exposure to CO as a surrogate of exposure to in epidemiologic and intervention studies of household air pollution. Because most health studies aim to evaluate daily or “usual” exposure, we limited our pooled analysis to studies of and CO concentration and/or exposure relationships for at least 24-hr in settings where biomass was the dominant household fuel. Our second objective was to evaluate whether the relationships estimated under one set of conditions are transportable to other conditions.

We provide a timely assessment of CO exposure as a surrogate of exposure, as a systematic review has been lacking but is critical to exposure measurement method selection for ongoing (Rosa et al. 2014; Klasen et al. 2013; Tielsch et al. 2014; Jack et al. 2015; NIH 2015) randomized controlled trials and other epidemiologic studies.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria for the Systematic Review

We searched publications included in the electronic database PubMed (from 1966 to present; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) and the Science Citation index, as well as the electronic databases Ovid MEDLINE® In-Process & Other NonIndexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE® Daily, Ovid OLDMEDLINE®, (1946 to present, http://ospguides.ovid.com/OSPguides/medline.htm) and Embase (1947 to present, http://www.elsevier.com/embase). We searched for combinations of the key words “carbon monoxide” or “CO” and “indoor air pollution” or “indoor*” or “house*” or “home*” or “personal exposure and particulate*” or “PM*” and “biomass or coal” or “fuel*” or “wood*” or “dung” or “crop” or “agricultural residue*.” The search was restricted to articles available in English, French, Spanish, or Chinese. We retained articles for which cooking area or personal measurements of PM and CO were done concurrently in a setting where biomass was burned for cooking and/or heating. Two researchers independently extracted information from these articles and hand-searched their reference lists to identify additional publications for retrieval. Finally, we contacted 15 researchers to directly obtain data from published and unpublished studies with paired PM and CO measurements. These studies were identified from the literature review and recent conference proceedings or academic meetings. We adhered to systematic review guidelines from PRISMA-P guidelines and the Cochrane Collaboration (Van Tulder et al. 2003; Moher et al. 2015).

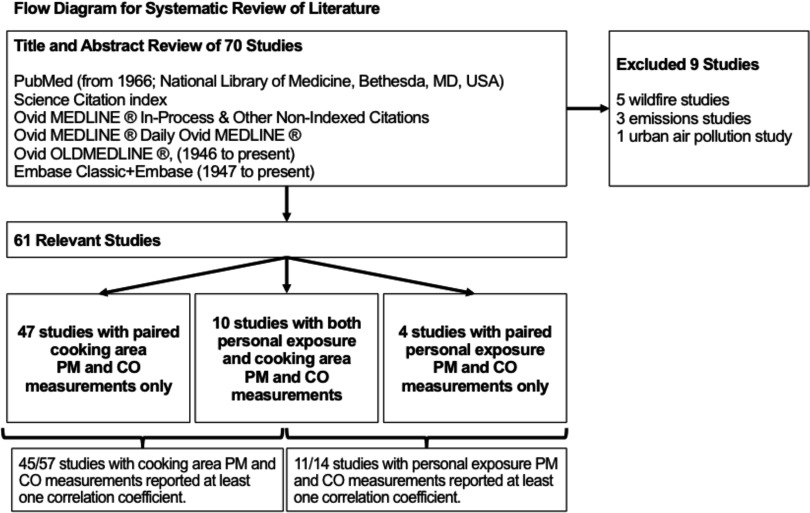

We classified studies retained for this review into two groups (Figure 1): studies with paired measurements of personal PM and CO exposures or stationary PM and CO concentrations in cooking areas. Though personal exposures were our primary interest, we reviewed studies with paired cooking area measurements because they are more common than studies with personal exposure (Balakrishnan et al. 2011; Clark et al. 2013) and may shed additional light on the relationship for personal exposures. For every study, the following information was extracted: authors, year of publication, year(s) of data collection, location, season(s), description of setting, elevation, description of study population (see Table S1), stove types, cooking location, cooking area ventilation, fuel types, other local air pollution sources, number of paired PM and CO measurements, pollutant measurement methods (i.e., protocols, instrumentation, quality assurance, quality control measures), and reported correlation coefficients. When information was not reported, we requested it from corresponding authors.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic search of literature for review.

Compiling Paired and CO Measurements for Pooled Data Analysis

We contacted the corresponding authors of studies identified in our systematic review to obtain the paired and CO data. If authors did not respond but the data were available in published studies, we downloaded those data. We also requested information on the stoves and fuels used, stove ventilation, other local air pollution sources, season of data collection, level of urbanicity (rural vs. peri-urban/urban), and and CO measurement methods. If these variables were unavailable for individual observations, we assigned them at the study level based on the information reported in the manuscript or communication with authors.

We obtained 2,048 paired and CO measurements and covariate data from 9 studies of personal and CO exposures () and 18 studies of cooking area and CO concentrations (). Personal exposure data were obtained from authors for 6 studies and extracted from tables or figures from 3 studies (Fitzgerald et al. 2012; McCracken et al. 2013; Naeher et al. 2000b). For paired cooking area measurements, data were obtained from authors of 9 studies, and we extracted data from 9 studies (Naeher et al. 2000a; Naeher et al. 2001; Park and Lee 2003; Chengappa et al. 2007; Dutta et al. 2007; Henkle et al. 2010; Fitzgerald et al. 2012; Chowdhury et al. 2013; Huboyo et al. 2014). We created dichotomous variables for covariates (see Table S2), including fuel use (exclusive vs. nonexclusive biomass use), whether other local sources of air pollution were reported, level of urbanicity, season (nonheating vs. heating), and CO measurement method (colorimetric-based vs. sensor-based). PM measurement type was almost exclusively gravimetric for personal exposures and a mix of gravimetric and optical measurements in cooking areas. We summarized the protocols and quality assurance/control procedures for personal PM and CO in Tables S3 and S4.

Statistical Analysis of the Pooled Data

We conducted a series of univariate and multivariate regression models to evaluate the coefficient of determination () and the slope between and CO, with separate models for personal exposure and cooking area measurements. Natural cubic spline functions with 2–5 degrees of freedom were used to evaluate whether the pollutant relationships were linear functions. Covariates including fuel use, other local sources of air pollution, urbanicity, season, and CO measurement method were added to the models to determine the extent to which their inclusion improved the . We incorporated a random intercept for study into the linear regression models to account for clustering of data by study. The values were compared to quantify the proportion of variation in explained by alone and after including other covariates in the models. Differences in the slope of on by fuel use, urbanicity, season, and CO measurement method were also compared to evaluate transportability (i.e., similarity) of the relationships between study conditions. Finally, in studies for which personal exposure and cooking area measurements of and CO were concurrent, we graphically compared the slopes of the personal exposure versus cooking area relationships to assess within-study transportability of the cooking area relationship to personal exposures.

As sensitivity analyses, we conducted the same models with untransformed CO. We also conducted the analyses without nonwood biomass (e.g., dung, charcoal), which may differ from wood in its proportional contribution of PM and CO to overall emissions (Jetter et al. 2012), and excluding studies not meeting the U.S. EPA (2016) Quality Assurance Guidelines for gravimetric PM analysis (). Finally, we compared the values for univariate and multivariate models within studies to investigate the extent to which individual-level covariate heterogeneity improved explanation of variation in by . All model assumptions were verified by routine diagnostic analysis of the residuals. The statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Systematic Review of the Literature

Our search criteria yielded 70 studies, including 2 unpublished studies that were eligible for review, representing measurements in 27 countries. Of these, we retained 61 studies for review after excluding 5 studies of outdoor wildfires, 3 studies of emissions measurements, and 1 urban outdoor air pollution study. Publication year ranged from 1968 to 2016, though most studies (92%) were published after 2000. Studies were conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa (), Latin America (), South and East Asia (), Eastern Mediterranean (), and Western Pacific ().

Studies with paired measurements of personal exposures to and CO in adults and/or children accounted for 23% () of all studies reviewed (Table 1). Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 268 paired measurements (). Twelve of the 14 studies enrolled women who were the primary household cooks; in 2 studies, all enrolled participants were pregnant (St. Helen et al. 2015; Wylie et al. 2016). One study enrolled children 15–61 months of age (Dionisio et al. 2012), and another (Naeher et al. 2000a) enrolled mother–child pairs in which both mother and child () wore the CO and monitors.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies with paired measurements of personal exposure to and CO.

| Author/year (country) | Fuel(s)a | Other local air pollution sources | CO/PM method | correlationf (correlation coeff; r) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO Sb/Dc | PM Gd/LSe | ||||

| Cynthia et al. 2008 (Mexico) | Wood | ETSg | S | LS | 0.82 () preintervention |

| 0.84 () postintervention | |||||

| Balakrishnan et al. 2015 (India) | Wood, dung | S | G | 0.49 () | |

| Commodore et al. 2013 (Peru) | Wood | S | LS | 0.41 (h) | |

| Dionisio et al. 2012 (The Gambia) | Wood | D | G | 0.22 () | |

| Ellegård and Egnéus 1993 (Zambia) | Wood, charcoal, electricity | ETS | D | G | NRi () |

| Fitzgerald et al. 2012 (Peru) | Wood | S | G | 0.68 () | |

| Hartinger et al. 2013 (Peru) | Wood | ETS | S | G | NR () |

| McCracken et al. 2013 (Guatemala) | Wood | S | G | 0.70 () | |

| Mukhopadhyay et al. 2012 (India) | Wood, dung, LPGj | S | G | NR () | |

| Naeher et al. 2000a (Guatemala) | Wood | D | G | 0.97 () | |

| Ni et al. 2016 (China) | Wood | ETS | D | G | 0.60 () |

| Peel JL, written and oral communication, 2016 (Honduras) | Wood | S | G | 0.57 () | |

| St. Helen et al. 2015 (Peru) | Wood, coal, LPG, kerosene | ETS | S | G | 0.33 () |

| Wylie et al. 2016 (Tanzania) | Wood, charcoal, kerosene | ETS; major road | D | G | 0.34 () |

Biomass (e.g., wood, crop residue, dung) and non-biomass fuels.

Sensor-based.

Colorimetric/diffusion-based.

Gravimetric.

Light-scattering.

Spearman correlation.

Environmental tobacco smoke.

4-Hr mean CO and concentrations.

Not reported.

Liquefied petroleum gas.

Personal and CO exposures were integrated over 22-, 24-, or 48-hr periods to represent “usual” daily exposure. Most studies ( of 14) measured personal exposures with gravimetric instruments. Nine studies used a sensor-based method for CO measurement, and five used a colorimetric dosimeter.

Studies of paired cooking area and CO concentrations comprised 93% () of those identified in this systematic review (see Table S5). Sample sizes ranged from 9 to 350 paired measurements (). Most stationary and CO concentrations were measured in kitchens and cooking areas located in the same building as the living quarters, although some were conducted in rooms adjacent to the kitchen or in separate cookhouses. In five studies (Fischer and Koshland 2007; Pearce et al. 2009; Leavey et al. 2015; Muralidharan et al. 2015; Saksena et al. 1992), and CO measurements were limited to cooking events, but the rest were integrated over 22-, 24-, or 48-hr periods. Light-scattering, optical techniques () and integrated, gravimetric techniques () were used for measurements. Of the studies with optical measurements, 85% measured CO with an electrochemical or optical sensor. Of studies with gravimetric measurements of , CO was measured with a sensor in 67% of studies () and with a colorimetric dosimeter in 33% of studies ().

Correlations between paired and CO personal exposure measurements.

Correlation coefficients (Spearman ) were reported or calculated for 11 of the 14 studies measuring personal exposures (Table 1). The highest correlation () was observed in the study with the smallest sample size, namely 12 observations from mother–child pairs using biomass in open fires and traditional stoves in Guatemala (Naeher et al. 2000a). In the remaining studies, the correlations ranged from to [; ; interquartile range ]. Personal correlations were generally higher for studies reporting exclusive use of biomass fuel (; ; ), conducted in rural settings (; ; ), and using sensor-based CO measurements (; ; ).

Correlations between paired measurements of cooking area and CO concentrations.

Correlation coefficients were reported or calculated in 45 of the 57 studies with paired and CO measurements in cooking areas (see Table S5) and ranged from to (; ). Overall, the correlations were higher for studies with exclusive biomass use (; ; ) than use of multiple fuels (; ; ) but the same in rural (, , ) and peri-urban settings (; ; ). The correlations were similar for all combinations of and CO measurement techniques and in homes with or without a tobacco or pipe smoker. In one-third of studies reviewed, the authors reported correlation coefficients for subscript-group analyses (see Table S5). Within studies, the correlation was often higher for observations in rural settings or where wood was burned in open fires or traditional stoves.

Results from Pooled Data Analyses of Paired and CO Measurements

Paired personal exposures to and CO.

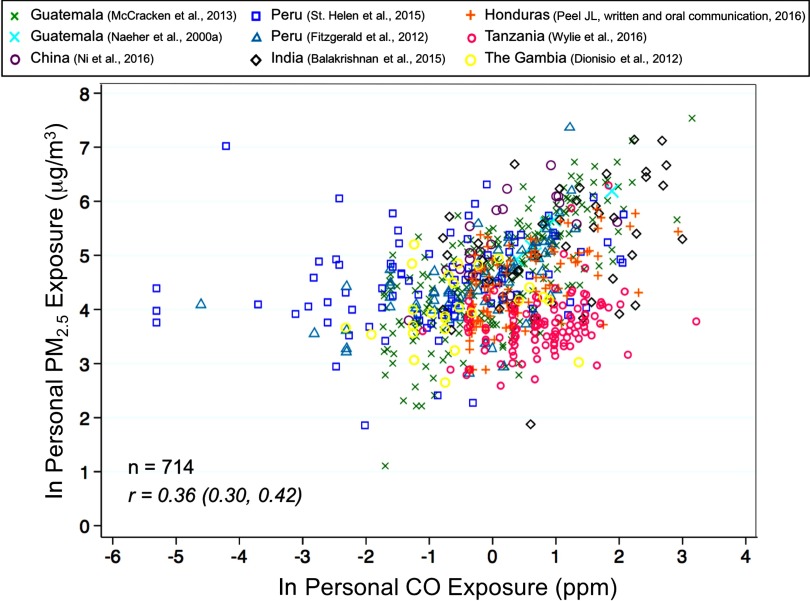

The and CO personal exposure means, ranges (see Table S6), and correlations varied between studies (Figure 2). The overall correlation was [95% confidence intervals (CI): 0.30, 0.42; ] (Figure 2a). The majority of study participants lived in rural settings (68%) and used biomass fuels exclusively (80%). Participants who did not use biomass exclusively also used other fuels including liquefied petroleum gas (LPG; 9%), charcoal (6%), kerosene (3%), coal (2%), and electricity (0.1%). The correlation among only those living with a tobacco or pipe smoker () was low (, 95% CI: , 0.40). All exposure measurements were gravimetric. Most (75%) CO observations were sensor-based, and the rest were colorimetric-based.

Figure 2.

Paired personal and personal CO exposure measurements for (a) all observations combined from nine studies and for (b–i) individual studies. One outlying data point for Tanzania (CO: 25.2 ppm, : ), one for Peru (CO: 25.2 ppm, : ), two for Guatemala (CO: 18.5 ppm, : ; CO: 23.6 ppm, : ), and two for India (CO: 14.7 ppm, : ; CO: 9.5 ppm, : ) are not pictured to improve data visualization. 2h has an expanded CO concentration range along the horizontal axis.

Associations between personal exposures to and CO in the pooled analysis.

Pollutant concentrations for personal exposure to and CO were not normally distributed (right-skewed), and were natural log-transformed prior to evaluating their relationship using scatter plots (Figure 3) and locally weighted scatter plot smoothing and natural cubic spline models (see Figure S1a,b). Visual inspection of these plots indicated that the personal relationship was approximately linear.

Figure 3.

Natural log-transformed personal exposures versus natural log-transformed CO personal exposures plotted for nine unique studies. The Spearman correlation ( confidence intervals) for all observations () is presented at the bottom left of the figure.

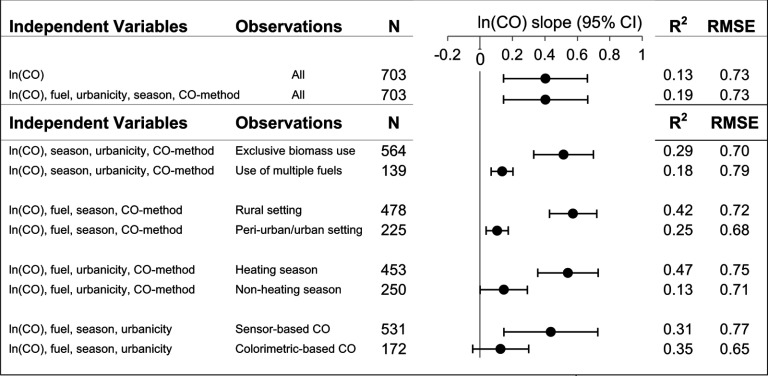

None of the univariate or multivariate linear regression models explained more than 50% of the variance in exposure. The proportion of variation in exposure explained by ln(CO) exposure was 13% with CO alone in the model and 19% in the model including fuel use, urbanicity, season, and CO method (Figure 4). Restricting the multivariate analysis to observations conducted in rural settings () or during the heating season () resulted in the highest explanation of variation in , namely 42% and 47%, respectively (Figure 4). Excluding two studies not meeting the U.S. EPA Quality Assurance Guidelines for gravimetric analysis did not substantially change our results (; ).

Figure 4.

Comparison of estimates of the slope of on ( confidence intervals) for personal exposures using univariate and multivariate linear regression models for the full data set and stratified by subsets of the data. The values and root mean squared error (RMSE) for each model are reported to the right of the plotted slope. Note: CI, confidence interval; RMSE, root mean squared error.

We observed significant differences in the slope by fuel use, level of urbanicity, and season (all interaction ). The slope was three to five times greater for measurements with exclusive use of biomass fuel, in rural settings, and during the heating season (Figure 4). In one study, the relationship also varied by whether the measurements were conducted pre- versus postintervention. In rural Peru (Fitzgerald et al. 2012), the slope of on was 0.50 (95% CI: 0.30, 0.70; ) among participants cooking with open fires, which was twice that of the slope among participants using chimney stoves (0.22, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.42; ) in the same setting (interaction ).

Paired stationary concentrations of and CO in cooking areas.

Cooking area and CO concentration means and ranges (see Table S7) and the strength of the correlation varied by study (; ; ; ). After combining the paired cooking area and CO concentrations from these studies, the correlation was (; 95% CI: 0.42–0.50) but improved to (; 95% CI: ) after removing 350 observations (26% of all observations) from a study in India with a correlation of (Balakrishnan et al. 2013). The CO measurements in the India data set had minimal variability (range: ; IQR: ), whereas the PM measurements ranged from . As the low CO variability could be attributable to instrument failure, these data were excluded from subsequent analyses. Of the remaining 981 observations, biomass was the primary cooking fuel for 82% () of observations, followed by LPG (12%), dung (4%), kerosene (0.5%), coal (1.4%), and electricity (0.1%). Over 86% () of observations were conducted in rural settings, and 64% () took place during the nonheating season.

Associations between cooking area concentrations of and CO in the pooled analysis.

A natural cubic spline model of and with three knots was consistent with a linear relationship (see Figure S2). The proportion of variation in concentrations explained by ln(CO) concentrations was 48% in both the univariate and the multivariate models, which included fuel use, setting, season, and CO method (Figure 5). The slope for cooking area measurements was twice as large in homes exclusively using biomass fuels compared with homes using multiple fuels (interaction ) and in rural compared with peri-urban settings (interaction ) (see Figure S3). The slope for cooking area measurements did not significantly differ by season (interaction ) or CO method (interaction ).

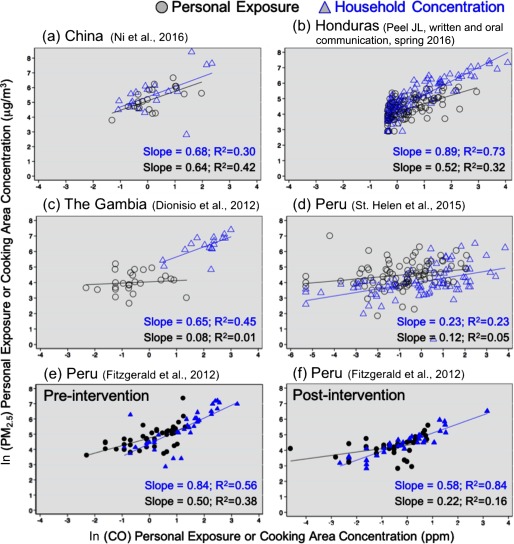

Figure 5.

Paired personal and cooking area and CO (24- or 48-hr integrated concentrations) for (a) China (Ni et al. 2016), (b) Honduras (Peel JL, written and oral communication, spring 2016), (c) The Gambia (Dionisio et al. 2012), (d) Peru (St. Helen et al. 2015), and Peru (e) pre- and (f) postintervention (Fitzgerald et al. 2012). The and slope of the relationship is shown for cooking area measurements (blue) and personal exposures (black).

Comparison of personal exposure and cooking area correlations and slopes.

For five studies (Dionisio et al. 2012; Fitzgerald et al. 2012; Ni et al. 2016; Peel JL, written and oral communication, 2016; St. Helen et al. 2015), personal exposure and cooking area and CO measurements were collected concurrently (Figure 5). With the exception of a study in China (Ni et al. 2016), the value was considerably higher for cooking area measurements than for personal exposures in the same study, suggesting that studies planning to use personal CO exposures as a surrogate for personal exposures would benefit from prior validation studies of personal exposure measurements, rather than cooking area measurements alone. In four of the five studies shown in Figure 5, the slope of on concentrations in cooking areas was two to eight times steeper than the slope of on exposures in the same study, which further suggests that use of cooking area concentrations to develop a model to estimate personal from measurements of personal CO exposure could lead to biased estimates.

Conducting our multivariate models with untransformed CO concentrations and exposures did not change our overall results (see Tables S8 and S9). In a subset of studies, adding covariates at the individual level in the models led to modest changes (3–19%) in the explanation of variation in ln(PM) explained by ln(CO) in the fully adjusted model relative to the univariate model (see Table S10). Removing observations where dung () or wood-charcoal () or coal () was used as the primary fuel with biomass did not appreciably change our results (data not shown). The variance inflation factors for our independent variables did not exceed 2.5, indicating a lack of multicollinearity.

Discussion

Our results suggest that exposure to CO is not a consistently valid surrogate of exposure to in settings with household air pollution, as indicated by low-to-moderate personal correlations [range: ; ]. None of the multivariate regression models explained of the variation in personal exposures. Further, the personal relationship was not transportable across different energy-use and environmental settings, suggesting that, if personal CO exposure is pursued as a surrogate measure of personal exposure, a separate validation may be needed for each unique study setting and, within studies, potentially each season or pre- versus post-stove/fuel intervention.

We found a stronger correlation between personal and CO exposures among exclusive biomass users relative to mixed fuel users (), supporting previous studies (Naeher et al. 2000a; Naeher et al. 2000b; McCracken et al. 2013). This finding is consistent with results from stove emission tests in laboratory and field settings. For example, Jetter et al. (2012) observed a higher coefficient of determination for versus CO emissions from biomass stoves compared with nonbiomass stoves during Water Boiling Tests (see Figure S4). This study and others describe fundamental sources of variability in combustion conditions and energy-use behaviors that limit the strength and consistency of the correlation we may expect for and CO exposures and concentrations in real-world settings with biomass combustion (Zhang et al. 2000; Roden et al. 2009; Shen et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2012; Shen et al. 2013). With widespread use of multiple stoves and fuels (i.e., stove stacking), exclusive biomass use is increasingly less common (Masera and Navia 1997; Masera et al. 2000; Ruiz-Mercado et al. 2011, Rehfuess et al. 2014; Ni et al. 2016;) and may reduce the number of settings in which validation studies will demonstrate CO to be a valid PM surrogate.

We observed a stronger personal relationship for measurements conducted in rural versus peri-urban settings (; interaction ), likely because densely populated peri-urban neighborhoods may have more community (i.e., solid waste burning) and regional pollution. At the same time, a stronger relationship for personal exposure measurements conducted in the heating season relative to the nonheating season (; interaction ) may reflect the greater proportion of time people spend indoors next to the fire, which is also where stationary indoor monitors are usually located. Notably, the for the personal exposure relationship in the heating season is almost identical to the cooking area relationship (0.47 vs. 0.46). Separately, we found that the personal relationship was modified significantly by season (interaction ), but the cooking area relationship was not (interaction ). This finding supports recent studies showing that personal exposures are impacted by other (i.e. noncooking) air pollution sources (Baumgartner et al. 2014; Huang et al. 2015; Secrest et al. 2017). These other air pollution sources impact noncooking area measurements and weaken the basis for transportability of the cooking area relationship to personal exposures. Using a cooking area relationship to estimate personal from measurements of personal CO exposure may yield inaccurate results, as our graphical comparison of these two relationships from the same studies suggests (Figure 5).

The exposure relationships may also vary by age or gender. Although 24-hr CO and exposures were measured in participants ranging from 18 months to 90 years of age, most exclusively measured adult women’s exposures, highlighting the limited data on exposures in infants and young children and the need to reduce technological barriers to measuring their exposure. No studies evaluated this relationship in men, though it is unlikely that the relationship would be stronger in men who, in many settings, are less likely to be the primary cooks and more likely to spend time outside of the home.

The type and range of pollutants of interest may vary depending on the health endpoint. Though the exact PM components responsible for its health impacts are unclear, there is strong and consistent evidence that both short- and long-term exposures to are associated with a range of clinical health outcomes in adults and children (WHO 2007; Chen et al. 2008; U.S. EPA 2009; Brook et al. 2010), including a number of PM exposure–response studies conducted in settings of biomass burning (Ezzati and Kammen 2001; Smith et al. 2011; Baumgartner et al. 2011; Norris et al. 2016). The evidence base for direct health impacts of CO exposure, beyond acute poisoning, is less strong. Animal studies indicate that fetal carboxyhemoglobin levels equilibrate with maternal levels (Longo 1977), and that very high maternal CO exposures are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including pregnancy loss and low birth weight (Astrup et al. 1972; Garvey and Longo 1978). In epidemiologic studies, exposure to low-to-moderate CO concentrations in pregnant women was associated with reduced fetal growth in some studies (Ritz and Yu 1999; Ha et al. 2001; Gouveia et al. 2004; Salam et al. 2005) but not others (Alderman et al. 1987; Koren et al. 1991; Chen et al. 2002). Notably, a recent study that measured both personal and personal CO exposure in pregnant Tanzanian women cooking with biomass stoves found that only exposure was associated with adverse birth outcomes (Wylie et al. 2016), supporting a similar finding among pregnant women in the urban United States (Parker et al 2005).

A strength of our pooled analysis is the inclusion of multiple independent variables that have been shown to influence the relationship. Still, it is possible that inclusion of other individual- or study-level variables could further improve the ability of CO to predict PM exposures or concentrations. For example, we did not have access to detailed socio-demographic data for study participants and could not include variables for altitude, monitor placement, or stove type because these variables were collinear with study, measurement type, and fuel type, respectively, and were thus excluded from the models.

Though our systematic review revealed inconsistencies in the reporting of quality assurance and quality control protocols for and CO measurements, which are subject to systematic error and may introduce bias, we recognize that investigators have to balance the scientific, logistical, technical, and cost trade-offs in selecting an exposure metric for their study. Standardized and transparent reporting could improve the comparability of pollution measurements collected across diverse settings. Such reporting would include, for example, filter handling, collection, and transport; field and lab blank correction; duplicate precision estimates, if possible; method detection limits and instrument sensitivity; instrument flow rate precision estimates; and traceability and calibration levels of gas standards used to calibrate CO sensors. Then, the trade-offs in pollutant selection, study design, and measurement precision, stability, practicality, and number—inherent to efforts to reduce exposure misclassification for long-term air pollution exposures (McCracken et al. 2009; Pillarisetti 2016)—could be evaluated more consistently across settings. Further, improving our collective assessment of these trade-offs would bring to light more suitable and effective approaches and technologies to measure exposure, especially among young children and infants, for whom we have the least information on PM exposure (Balakrishnan et al. 2011; Clark et al. 2013).

Conclusions

Our systematic review and pooled analysis suggest that personal CO exposures are a poor surrogate of measured personal PM exposures, even when biomass is exclusively burned. Our conclusions support those reached in recent studies reporting low correlations for cooking area concentrations (Klasen et al. 2015; Bartington et al. 2016). The relationship between cooking area and CO concentrations in this review was stronger than for personal exposures, potentially due to the closer proximity of stationary monitors to the solid fuel emission source, but still the variation in ln(CO) did not explain more than 48% of the variation in . Based on the evidence presented in this analysis, to use CO exposure as a surrogate for PM exposure would require repeated validation studies, especially if study conditions change over time. Lowering the barriers to exposure assessment, particularly for infants and young children, is an important direction for future research. Recent developments in portable lightweight monitors that are virtually silent and low-profile (Birch et al. 2015; Volckens et al. 2017) could expand the feasibility of PM exposure assessment to different populations and settings. Given that is likely one of the important drivers of the health effects associated with air pollution exposure, further research and development is needed to minimize measurement error, to reduce the logistical and technological challenges of large-scale PM exposure assessment, and to identify better surrogate measures of exposure and dose, potentially including internal biomarkers, for epidemiologic and intervention studies involving household air pollution.

Supplemental Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Ni, S. Pollard, O. Adetona, and M. Bechle for assistance with data compilation. This publication was made possible by U.S. EPA grant 83542201. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the grantee and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. EPA. Further, the U.S. EPA does not endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services mentioned in the publication. J.B. was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigator Award 141959.

References

- Alderman BW, Baron AE, Savitz DA. 1987. Maternal exposure to neighborhood carbon monoxide and risk of low infant birth weight. Public Health Rep 102(4):410–414, PMID: 3112852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D, Linnes JC, Bolton S, Larson T. 2014. Ventilated cookstoves associated with improvements in respiratory health-related quality of life in rural Bolivia. J Public Health 36(3):460–466, PMID: 23965639, 10.1093/pubmed/fdt086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alnes LW, Mestl HE, Berger J, Zhang H, Wang S, Dong Z, et al. 2014. Indoor PM and CO concentrations in rural Guizhou, China. Energy Sustain Dev 21:51–59, 10.1016/j.esd.2014.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong BG. 1998. Effect of measurement error on epidemiological studies of environmental and occupational exposures. Occup Environ Med 55(10):651–656, PMID: 9930084, 10.1136/oem.55.10.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong BG. 2004. Exposure measurement error: consequences and design issues. Exposure Assessment in Occupational and Environmental Epidemiology. Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, ed. New York, NY:Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Astrup P, Trolle D, Olsen HM, Kjeldsen K. 1972. Effect of moderate carbon monoxide exposure on fetal development. Lancet 2(7789):1220–1222, PMID: 4117709, 10.1016/S0140-6736(72)92270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan K, Ghosh S, Ganguli B, Sambandam S, Bruce N, Barnes DF, et al. 2013. State and national household concentrations of PM2.5 from solid cookfuel use: results from measurements and modeling in India for estimation of the global burden of disease. Environ Health 12(1):77, 10.1186/1476-069X-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan K, Sambandam S, Ghosh S, Mukhopadhyay K, Vaswani M, Arora NK, et al. 2015. Household air pollution exposures of pregnant women receiving advanced combustion cookstoves in India: implications for intervention. Ann Glob Health 81(3):375–385, PMID: 26615072, 10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan K, Thangavel G, Ghosh S, Sambandam S, Mukhopadhyay K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. , 2011. The Global Household Air Pollution Database 2011 (Version 3.0).

- Bartington SE, Bakolis I, Devakumar D, Kurmi OP, Gulliver J, Chaube G, et al. 2016. Patterns of domestic exposure to carbon monoxide and particulate matter in households using biomass fuel in Janakpur, Nepal. Environ Pollut 220(pt A):38–45, PMID: 27707597, 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.08.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner J, Schauer JJ, Ezzati M, Lu L, Cheng C, Patz J, et al. 2011. Patterns and predictors of personal exposure to indoor air pollution from biomass combustion among women and children in rural China. Indoor Air 21(6):479–488, PMID: 21692855, 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2011.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner J, Zhang Y, Schauer JJ, Huang W, Wang Y, Ezzati M. 2014. Highway proximity and black carbon from cookstoves as a risk factor for higher blood pressure in rural China. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(36):13229–13234, PMID: 25157159, 10.1073/pnas.1317176111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch A, Hystad P, Arku R, Volkens J, Miller-Lionberg D, Quinn C, et al. 2015. Household and personal air pollution monitoring in two communities in rural India using established and prototype devices. We-P-30. 34th Annual Conference of the International Society of Exposure Science, Nevada, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bonjour S, Adair-Rohani H, Wolf J, Bruce NG, Mehta S, Prüss-Ustün A, et al. 2013. Solid fuel use for household cooking: country and regional estimates for 1980–2010. Environ Health Perspect 121(7):784–790, PMID: 23674502, 10.1289/ehp.1205987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA III, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. 2010. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121(21):2331–2378, 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181dbece1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce N, McCracken J, Albalak R, Schei MA, Smith KR, Lopez V, et al. 2004. Impact of improved stoves, house construction and child location on levels of indoor air pollution exposure in young Guatemalan children. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 14:S26–S33, PMID: 15118742, 10.1038/sj.jea.7500355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EM, Shan M, Yang X, Li J, Baumgartner J. 2014. Pollutant emissions and energy efficiency of Chinese gasifier cooking stoves and implications for future intervention studies. Environ Sci Technol 48(1):6461–6467, PMID: 24784418, 10.1021/es405723w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Goldberg MS, Villeneuve PJ. 2008. A systematic review of relation between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and chronic disease. Rev Environ Health 23(4):243–296, PMID: 19235364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Yang W, Jennison BL, Goodrich A, Omaye ST. 2002. Air pollution and birth weight in northern Nevada, 1991–1999. Inhal Toxicol 14(2):141–157, PMID: 12122577, 10.1080/089583701753403962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Roden CA, Bond TC. 2012. Characterizing biofuel combustion with Patterns of Real-Time Emission Data (PaRTED). Environ Sci Technol 46(11):6110–6117, PMID: 22533493, 10.1021/es3003348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chengappa C, Edwards R, Bajpai R, Shields KN, Smith KR. 2007. Impact of improved cookstoves on indoor air quality in the Bundelkhand region in India. Energy Sustain Dev 11(2):33–44, 10.1016/S0973-0826(08)60398-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury Z, Campanella L, Gray C, Al Masud A, Mater-Kenyon J, Pennise D, et al. 2013. Measurement and modeling of indoor air pollution in rural households with multiple stove interventions in Yunnan, China. Atmos Environ 67:161–169, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.10.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Peel JL, Balakrishnan K, Breysse PN, Chillrud SN, Naeher LP, et al. 2013. Health and household air pollution from solid fuel use: the need for improved exposure assessment. Environ Health Perspect 121(10):1120–1128, PMID: 23872398, 10.1289/ehp.1206429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commodore AA, Hartinger SM, Lanata CF, Mäusezahl D, Gil AI, Hall DB, et al. 2013. A pilot study characterizing real time exposures to particulate matter and carbon monoxide from cookstove related woodsmoke in rural Peru. Atmos Environ 79:380–384, PMID: 24288452, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cynthia AA, Edwards RD, Johnson M, Zuk M, Rojas L, Jiménez RD, et al. 2008. Reduction in personal exposures to particulate matter and carbon monoxide as a result of the installation of a Patsari improved cook stove in Michoacan, Mexico. Indoor Air 18(2):93–105, PMID: 18333989, 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2007.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionisio KL, Howie SR, Dominici F, Fornace KM, Spengler JD, Adegbola RA, et al. 2012. Household concentrations and exposure of children to particulate matter from biomass fuels in The Gambia. Environ Sci Technol 46(6):3519–3527, PMID: 22304223, 10.1021/es203047e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionisio KL, Howie S, Fornace KM, Chimah O, Adegbola RA, Ezzati M. 2008. Measuring the exposure of infants and children to indoor air pollution from biomass fuels in The Gambia. Indoor Air 18(4):317–327, PMID: 18422570, 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2008.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix-Cooper L, Eskenazi B, Romero C, Balmes J, Smith KR. 2012. Neurodevelopmental performance among school age children in rural Guatemala is associated with prenatal and postnatal exposure to carbon monoxide, a marker for exposure to woodsmoke. Neurotoxicology 33(2):246–254, PMID: 21963523, 10.1016/j.neuro.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta K, Shields KN, Edwards R, Smith KR. 2007. Impact of improved biomass cookstoves on indoor air quality near Pune, India. Energy Sustain Dev 11(2):19–32, 10.1016/S0973-0826(08)60397-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegård A, Egnéus H. 1993. Urban energy: exposure to biomass fuel pollution in Lusaka. Energy Policy 21(5):615–622, 10.1016/0301-4215(93)90044-G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Kammen DM. 2001. Indoor air pollution from biomass combustion and acute respiratory infections in Kenya: an exposure-response study. Lancet 358(9282):619–624, PMID: 11530148, 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Mbinda BM, Kammen DM. 2000. Comparison of emissions and residential exposure from traditional and improved cookstoves in Kenya. Environ Sci Technol 34(4):578–583, 10.1021/es9905795. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SL, Koshland CP. 2007. Daily and peak 1-h indoor air pollution and driving factors in a rural Chinese village. Environ Sci Technol 41(9):3121–3126, PMID: 17539514, 10.1021/es060564o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald C, Aguilar-Villalobos M, Eppler AR, Dorner SC, Rathbun SL, Naeher LP. 2012. Testing the effectiveness of two improved cookstove interventions in the Santiago de Chuco Province of Peru. Sci Total Environ 420:54–64, PMID: 22309740, 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey DJ, Longo LD. 1978. Chronic low level maternal carbon monoxide exposure and fetal growth and development. Biol Reprod 19(1):8–14, PMID: 687711, 10.1095/biolreprod19.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators, Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L, Anderson HR, Bachman VF, Biryukov S, et al. , 2015. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386(10010):2287–2323, PMID: 27733284, 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia N, Bremner SA, Novaes HMD. 2004. Association between ambient air pollution and birth weight in São Paulo, Brazil. J Epidemiol Community Health 58:11–17, PMID: 14684720, 10.1136/jech.58.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnieri MJ, Diaz JV, Basu C, Diaz A, Pope D, Smith KR, et al. 2014. Effects of woodsmoke exposure on airway inflammation in rural Guatemalan women. PLoS One 9:e88455, PMID: 24625755, 10.1371/journal.pone.0088455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha EH, Hong YC, Lee BE, Woo BH, Schwartz J, Christiani DC. 2001. Is air pollution a risk factor for low birth weight in Seoul? Epidemiology 12(6):643–648, PMID: 11679791, 10.1097/00001648-200111000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartinger SM, Commodore AA, Hattendorf J, Lanata CF, Gil AI, Verastegui H, et al. 2013. Chimney stoves modestly improved indoor air quality measurements compared with traditional open fire stoves: results from a small-scale intervention study in rural Peru. Indoor Air 23(4):342–352, PMID: 23311877, 10.1111/ina.12027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkle J, Mandzuk C, Emery E, Schrowe L, Sevilla-Martir J. 2010. Global health and international medicine: Honduras Stove Project. Hisp Health Care Int 8(1):36–46, 10.1891/1540-4153.8.1.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Baumgartner J, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Schauer JJ. 2015. Source apportionment of air pollution exposures of rural Chinese women cooking with biomass fuels. Atmos Environ 104:79–87, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.12.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huboyo HS, Tohno S, Lestari P, Mizohata A, Okumura M. 2014. Characteristics of indoor air pollution in rural mountainous and rural coastal communities in Indonesia. Atmos Environ 82:343–350, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.10.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jack DW, Asante KP, Wylie BJ, Chillrud SN, Whyatt RM, Ae-Ngibise KA, et al. 2015. Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study (GRAPHS): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 16(1):420, PMID: 26395578, 10.1186/s13063-015-0930-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetter J, Zhao Y, Smith KR, Khan B, Yelverton T, Decarlo P, et al. 2012. Pollutant emissions and energy efficiency under controlled conditions for household biomass cookstoves and implications for metrics useful in setting international test standards. Environ Sci Technol 46(19):10827–10834, PMID: 22924525, 10.1021/es301693f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasen E, Miranda JJ, Khatry S, Menya D, Gilman RH, Tielsch JM, et al. 2013. Feasibility intervention trial of two types of improved cookstoves in three resource-limited settings: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 14:327, PMID: 24112419, 10.1186/1745-6215-14-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasen EM, Wills B, Naithani N, Gilman RH, Tielsch JM, Chiang M, et al. 2015. Low correlation between household carbon monoxide and particulate matter concentrations from biomass-related pollution in three resource-poor settings. Environ Res 142:424–431, PMID: 26245367, 10.1016/j.envres.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren G, Sharav T, Pastuszak A, Garrettson LK, Hill K, Samson I, et al. 1991. A multicenter, prospective study of fetal outcome following accidental carbon monoxide poisoning in pregnancy. Reprod toxicol 5:397–403, PMID: 1806148, 10.1016/0890-6238(91)90002-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavey A, Londeree J, Priyadarshini P, Puppala J, Schechtman KB, Yadama G, et al. 2015. Real-time particulate and CO concentrations from cookstoves in rural households in Udaipur, India. Environ Sci Technol 49(12):7423–7431, PMID: 25985217, 10.1021/acs.est.5b02139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo LD. 1977. The biological effects of carbon monoxide on the pregnant woman, fetus and newborn infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol 129(1):69–103, PMID: 561541, 10.1016/0002-9378(77)90824-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masera OR, Navia J. 1997. Fuel switching or multiple cooking fuels? Understanding inter-fuel substitution patterns in rural Mexican households. Biomass Bioenergy 12(5):347–361, 10.1016/S0961-9534(96)00075-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masera OR, Saatkamp BD, Kammen DM. 2000. From linear fuel switching to multiple cooking strategies: a critique and alternative to the energy ladder model. World Dev 28(12):2083–2103, 10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00076-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken JP, Schwartz J, Bruce N, Mittleman M, Ryan LM, Smith KR. 2009. Combining individual-and group-level exposure information: child carbon monoxide in the Guatemala woodstove randomized control trial. Epidemiology 20:127–136, 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818ef327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken JP, Schwartz J, Diaz A, Bruce N, Smith KR. 2013. Longitudinal relationship between personal CO and personal PM2.5 among women cooking with wood-fired cookstoves in Guatemala. PLoS One 8(2):e55670, PMID: 23468847, 10.1371/journal.pone.0055670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. 2015. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 4:1, PMID: 25554246, 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay R, Sambandam S, Pillarisetti A, Jack D, Mukhopadhyay K, Balakrishnan K, et al. 2012. Cooking practices, air quality, and the acceptability of advanced cookstoves in Haryana, India: an exploratory study to inform large-scale interventions. Glob Health Action 5(1):1–13, PMID: 22989509, 10.3402/gha.v5i0.19016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muralidharan V, Sussan TE, Limaye S, Koehler K, Williams DL, Rule AM, et al. 2015. Field testing of alternative cookstove performance in a rural setting of Western India. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(2):1773–1787, PMID: 25654775, 10.3390/ijerph120201773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeher LP, Brauer M, Lipsett M, Zelikoff JT, Simpson CD, Koenig JQ, et al. 2007. Woodsmoke health effects: a review. Inhal Toxicol 19(1):67–106, PMID: 17127644, 10.1080/08958370600985875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeher LP, Leaderer BP, Smith KR. 2000a. Particulate matter and carbon monoxide in highland Guatemala: indoor and outdoor levels from traditional and improved wood stoves and gas stoves. Indoor Air 10:200–205, PMID: 10979201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeher LP, Smith KR, Leaderer BP, Mage D, Grajeda R. 2000b. Indoor and outdoor PM2.5 and CO in high-and low-density Guatemalan villages. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 10(3):544–551, PMID: 11140438, 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2000.010003200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeher LP, Smith KR, Leaderer BP, Neufeld L, Mage DT. 2001. Carbon monoxide as a tracer for assessing exposures to particulate matter in wood and gas cookstove households of highland Guatemala. Environ Sci Technol 35(3):575–581, PMID: 11351731, 10.1021/es991225g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni K, Carter EM, Schauer JJ, Ezzati M, Zhang Y, Niu H, et al. 2016. Seasonal variation in ambient, household, and personal air pollution exposures of women using traditional wood stoves in the Tibetan Plateau: baseline assessment for an energy intervention study. Environ Int 94:449–457, 10.1016/j.envint.2016.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2015. “Household Air Pollution (HAP) Health Outcomes Trial (UM1).” RFA-HL-16-012, https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-HL-16-012.html [accessed 22 June 2017].

- Norris C, Goldberg MS, Marshall JD, Valois MF, Pradeep T, Narayanswamy M, et al. 2016. A panel study of the acute effects of personal exposure to household air pollution on ambulatory blood pressure in rural Indian women. Environ Res 147:331–342, PMID: 26928412, 10.1016/j.envres.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcross A, Chowdhury Z, McCracken J, Canuz E, Smith KR. 2010. Estimating personal PM2.5 exposures using CO measurements in Guatemalan households cooking with wood fuel. J Environ Monit 12(14):873–878, PMID: 20383368, 10.1039/b916068j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northcross AL, Hwang N, Balakrishnan K, Mehta S. 2015. Assessing exposures to household air pollution in public health research and program evaluation. Ecohealth 12(1):57–67, PMID: 25380652, 10.1007/s10393-014-0990-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochieng CA, Vardoulakis S, Tonne C. 2013. Are rocket mud stoves associated with lower indoor carbon monoxide and personal exposure in rural Kenya? Indoor Air 23(1):14–24, PMID: 22563898, 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2012.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Lee K. 2003. Particulate exposure and size distribution from wood burning stoves in Costa Rica. Indoor Air 13(3):253–259, PMID: 12950588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JD, Woodruff TJ, Basu R, Schoendorf KC. 2005. Air pollution and birth weight among term infants in California. Pediatrics 115(1):121–128, PMID: 15629991, 10.1542/peds.2004-0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce JL, Aguilar-Villalobos M, Rathbun SL, Naeher LP. 2009. Residential exposures to PM2.5 and CO in Cusco, a high-altitude city in the Peruvian Andes: a pilot study. Arch Environ Occup Health 64(4):278–282, PMID: 20007125, 10.1080/19338240903338205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel JL, Baumgartner J, Wellenius GA, Clark ML, Smith KR. 2015. Are randomized trials necessary to advance epidemiologic research on household air pollution? Curr Epidemiol Rep 2(4):263–270, 10.1007/s40471-015-0054-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillarisetti A. 2016. Long-term PM2.5 monitoring in kitchens cooking with wood: implications for measurement strategies. In “Inspecting What you Expect: Applying Modern Tools and Techniques to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Household Energy Interventions.” PhD Dissertation. Accessible via University of California, Berkeley library http://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/dissertations_theses. [Google Scholar]

- Pope CA III, Dockery DW. 2006. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. J Air Waste Manag Assoc 56(6):709–742, 10.1080/10473289.2006.10464485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope D, Diaz E, Smith-Sivertsen T, Lie RT, Bakke P, Balmes JR, et al. 2015. Exposure to household air pollution from wood combustion and association with respiratory symptoms and lung function in nonsmoking women: results from the RESPIRE trial, Guatemala. Environ Health Perspect 123:285–292, PMID: 25398189, 10.1289/ehp.1408200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfuess EA, Puzzolo E, Stanistreet D, Pope D, Bruce NG. 2014. Enablers and barriers to large-scale uptake of improved solid fuel stoves: a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect 122(2):120–130, PMID: 24300100, 10.1289/ehp.1306639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riojas-Rodriguez H, Schilmann A, Marron-Mares AT, Masera O, Li Z, Romanoff L, et al. 2011. Impact of the improved Patsari biomass stove on urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biomarkers and carbon monoxide exposures in rural Mexican women. Environ Health Perspect 119(9):1301–1307, PMID: 21622083, 10.1289/ehp.1002927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz B, Yu F. 1999. The effect of ambient carbon monoxide on low birth weight among children born in southern California between 1989 and 1993. Environ Health Perspect 107(1):17–25, PMID: 9872713, 10.1289/ehp.9910717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden CA, Bond TC, Conway S, Pinel ABO, MacCarty N, Still D. 2009. Laboratory and field investigations of particulate and carbon monoxide emissions from traditional and improved cookstoves. Atmos Environ 43(6):1170–1181, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.05.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Röllin HB, Mathee A, Bruce N, Levin J, Von Schirnding YER. 2004. Comparison of indoor air quality in electrified and un-electrified dwellings in rural South African villages. Indoor Air 14(3):208–216, PMID: 15104789, 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa G, Majorin F, Boisson S, Barstow C, Johnson M, Kirby M, et al. 2014. Assessing the impact of water filters and improved cook stoves on drinking water quality and household air pollution: a randomised controlled trial in Rwanda. PloS One 9(3):e91011, 10.1371/journal.pone.0091011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Mercado I, Masera O, Zamora H, Smith KR. 2011. Adoption and sustained use of improved cookstoves. Energy Policy 39(12):7557–7566, 10.1016/j.enpol.2011.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saksena S, Prasad R, Pal RC, Joshi V. 1992. Patterns of daily exposure to TSP and CO in the Garhwal Himalaya. Atmos Environ. Part A. General Topics 26(11):2125–2134, 10.1016/0960-1686(92)90096-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saksena S, Subida R, Büttner L, Ahmed L. 2007. Indoor air pollution in coastal houses of southern Philippines. Indoor Built Environ 16(2):159–168, 10.1177/1420326X07076783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salam MT, Millstein J, Li YF, Lurmann FW, Margolis HG, Gilliland FD. 2005. Birth outcomes and prenatal exposure to ozone, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter: results from the Children’s Health Study. Environ Health Perspect 113(11):1638–1644, PMID: 16263524, 10.1289/ehp.8111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secrest MH, Schauer JJ, Carter E, Baumgartner J. 2017. Particulate matter chemical component concentrations and sources in settings of household solid fuel use. Indoor Air, PMID: 28401994, 10.1111/ina.12389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen G, Yang Y, Wang W, Tao S, Zhu C, Min Y, et al. 2010. Emission factors of particulate matter and elemental carbon for crop residues and coals burned in typical household stoves in China. Environ Sci Technol 44(18):7157–7162, PMID: 20735038, 10.1021/es101313y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR. 1993. Fuel combustion, air pollution exposure, and health: the situation in developing countries. Annu Rev Energy Environ 18:529–566, 10.1146/annurev.energy.18.1.529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, McCracken JP, Thompson L, Edwards R, Shields KN, Canuz E, et al. 2010. Personal child and mother carbon monoxide exposures and kitchen levels: methods and results from a randomized trial of woodfired chimney cookstoves in Guatemala (RESPIRE). J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 20(5):406–416, PMID: 19536077, 10.1038/jes.2009.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KR, McCracken JP, Weber MW, Hubbard A, Jenny A, Thompson LM, et al. 2011. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 378(9804):1717–1726, PMID: 22078686, 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Sivertsen T, Díaz E, Pope D, Lie RT, Díaz A, McCracken J. 2009. Effect of reducing indoor air pollution on women's respiratory symptoms and lung function: the RESPIRE Randomized Trial, Guatemala. Am J Epidemiol 170(2):211–220, PMID: 19443665, 10.1093/aje/kwp100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman D. 2010. Approaches to uncertainty in exposure assessment in environmental epidemiology. Annu Rev Public Health 31:149–163, PMID: 20070202, 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Helen G, Aguilar-Villalobos M, Adetona O, Cassidy B, Bayer CW, Hendry R, et al. 2015. Exposure of pregnant women to cookstove-related household air pollution in urban and periurban Trujillo, Peru. Arch Environ Occup Health 70(1):10–18, PMID: 24215174, 10.1080/19338244.2013.807761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LM, Bruce N, Eskenazi B, Diaz A, Pope D, Smith KR. 2011. Impact of reduced maternal exposures to wood smoke from an introduced chimney stove on newborn birth weight in rural Guatemala. Environ Health Perspect 119(10):1489–1494, PMID: 21652290, 10.1289/ehp.1002928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsson S, Holmer B, Andjelic A, Lindén J, Cimerman S, Barregard L. 2014. Carbon monoxide concentrations in outdoor wood-fired kitchens in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso—implications for women’s and children’s health. Environ Monit Assess 186(7):4479–4492, PMID: 24652378, 10.1007/s10661-014-3712-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielsch JM, Katz J, Zeger SL, Khatry SK, Shrestha L, Breysse P, et al. 2014. Designs of two randomized, community-based trials to assess the impact of alternative cookstove installation on respiratory illness among young children and reproductive outcomes in rural Nepal. BMC Public Health 14:1271–1281, PMID: 25511324, 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency). 2009. Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter (Final Report). EPA/600/R-08/139F. Washington, DC:U.S. EPA. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA. 2016. Quality Assurance Guidance Document 2.12. Monitoring PM2.5 in Ambient Air Using Designated Reference or Class I Equivalent Methods. EPA-454/B-16-001. Washington, DC:U.S. EPA. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L; Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group, 2003. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 28(12):1290–1299, PMID: 12811274, 10.1097/01.BRS.0000065484.95996.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volckens J, Quinn C, Leith D, Mehaffy J, Henry CS, Miller‐Lionberg D. 2017. Development and evaluation of an ultrasonic personal aerosol sampler (UPAS). Indoor Air 27(2):409–416, PMID: 27354176, 10.1111/ina.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2007. Health Relevance of Particulate Matter from Various Sources. Copenhagen, Denmark:WHO, Regional Office for Europe; http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/78658/E90672.pdf [accessed May 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2014. WHO Indoor Air Quality Guidelines: Household Fuel Combustion. Geneva, Switzerland:WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylie BJ, Kishashu Y, Matechi E, Zhou Z, Coull B, Abioye AI, et al. 2016. Maternal exposure to carbon monoxide and fine particulate matter during pregnancy in an urban Tanzanian cohort. Indoor Air 27(1):136–146, 10.1111/ina.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip F, Christensen B, Sircar K, Naeher L, Bruce N, Pennise D, et al. 2017. Assessment of traditional and improved stove use on household air pollution and personal exposures in rural western Kenya. Environ Int 99:185–191, PMID: 27923586, 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JJ, Smith KR. 2007. Household air pollution from coal and biomass fuels in China: measurements, health impacts, and interventions. Environ Health Perspect 115(6):848–855, PMID: 17589590, 10.1289/ehp.9479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Smith KR, Ma Y, Jiang F, Qi W, Khalil MAK, et al. 2000. Greenhouse gases and other airborne pollutants from household stoves in China: a database for emission factors. Atmos Environ 34(26):4537–4549, 10.1016/S1352-2310(99)00450-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.