Abstract

AIDS is the leading killer of African Americans between the ages of 25 and 44, many of whom became infected when they were teenagers or young adults. The disparity in HIV infection rate among African Americans youth residing in rural Southern regions of the United States suggests that there is an urgent need to identify ways to promote early preventive intervention to reduce HIV-related risk behavior. The Strong African American Families (SAAF) program, a preventive intervention for rural African American parents and their 11-year-olds, was specially designed to deter early sexual onset and the initiation and escalation of alcohol and drug use among rural African American preadolescents. A clustered-randomized prevention trial was conducted, contrasting families who took part in SAAF with control families. The trial, which included 332 families, indicated that intervention-induced changes occurred in intervention-targeted parenting, which in turn facilitated changes in youths’ internal protective processes and positive sexual norms. Long-term follow up assessments when youth were 17 years old revealed that intervention-induced changes in parenting practices mediated the effect of intervention-group influences on changes in the onset and escalation of risky sexual behaviors over 65 months through its positive influence on adolescents’ self-pride and their sexual norms. The findings underscore the powerful effects of parenting practices among rural African American families that over time serve a protective role in reducing youth’s risk behavior, including HIV vulnerable behaviors.

Keywords: African American, Parenting, Rural, Adolescents, Sexual norms, Sexual risk taking, Prevention

Introduction

The rural Southern coastal plain that reaches across Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina is one of the most economically disadvantaged regions of the United States. In addition to facing disparate levels of poverty, this region comprises the highest population of African Americans (Dalaker 2001). These resource poor communities have been hit hard with a high prevalence of HIV/AIDS, and this chronic disease has become one of the most critical issues facing African Americans. AIDS is the leading killer of African Americans between the ages of 25 and 44, many of whom became infected when they were teenagers or young adults (CDC 2006). African Americans residing in the rural South are disproportionately infected by HIV at a rate that is 3 times that of the United States as a whole (23.2 and 7.3, respectively; Hall et al. 2005). Reasons why African Americans in general, and those in the South, in particular, are impacted disproportionately by HIV/AIDS remain unknown (Wyatt et al. 2008). Consistently offered explanations include young age at sexual debut, which is associated with a number of related risk factors, including the number of life time sexual partners, greater risk for unintended pregnancy, and higher exposure to risk for sexually transmitted infections (CDC 2006). In addition, several studies have documented the association between the use alcohol and drugs during sexual encounters that in turn interfere with youths’ ability to make safer sex decisions (Dee 2001; YRBS 2007). Behavioral choices made during middle childhood and adolescence place rural African American youth at risk for HIV infection, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and pregnancy, and forecast the likelihood that they will engage in high-risk behavior throughout adolescence and young adulthood (Guo et al. 2002; Kaestel et al. 2005).

Rural African American youth, who reside in poverty and disadvantage situations, are at particular risk of engaging in unsafe sexual practices, increasing their exposure to HIV (CDC 2006). The disparity in HIV infection rates among African American youth residing in rural Southern regions of the United States suggest the urgent need to identify ways to promote early preventive interventions to reduce HIV-related risk behavior. In the following section, we describe a family-based preventive intervention program, the Strong African American Families (SAAF) program, specially designed for rural African Americans to deter early sexual onset and the initiation and escalation of alcohol and drug use among rural African American preadolescents.

The families who participated in SAAF live in small towns and communities in rural Georgia, in which poverty rates are among the highest in the nation and unemployment rates are above the national average (Proctor and Dalaker 2003). Although 75% of primary caregivers work an average of 39 h per week, 50% of the total sample of families live below federal poverty standards and another 25% live within 150% of the poverty threshold. These families, which represent the rural Georgia counties in which they live (Boatright 2003), can best be described as working poor (Proctor and Dalaker 2003). Their poverty status reflects the dominance of low-wage, resource-intensive industries in these areas. For families with little discretionary income, residing in rural areas can be more challenging than living in urban areas due to restricted educational and employment opportunities, a lack of public transportation, a lack of recreational facilities for youth, and difficulties in obtaining treatment for physical health, mental health, and substance use problems (Tickamyer and Duncan 1990). For rural African American families, the challenge of overcoming the environmental obstacles associated with poverty and chronic economic stress is exacerbated by oppressive social structures and racial discrimination (see Murry et al. 2001; Tickamyer and Duncan 1990). Many African American families in rural Georgia thus live with chronic economic and contextual stress that has the potential to take a toll on adolescents.

These contextual and environmental factors were considered in the development, design, and implementation of the SAAF program. SAAF is a universal preventive intervention program that was developed based on over a decade of longitudinal, developmental research that the authors obtained with rural African American parents and youth (SAAF; Brody et al. 2004; Murry and Brody 2004). Findings from their works demonstrate that powerful factors protecting children and adolescents from engaging in risk behaviors originate in the family, particularly in African American parents’ caregiving practices (Brody et al. 2002; Murry et al. 2009). These practices play a pivotal role in youths’ positive development. Specifically, positive caregiver-youth relationships and positive parenting processes promote self-regulation, academic competence, psychological adjustment, and the avoidance of alcohol and substance use among rural African American youth (Brody et al. 2002; Murry et al. 2009). SAAF also was informed by other family centered intervention programs that inhibit adolescent risk behavior by enhancing parental and youth competence (Dishion and Kavanagh 2000; Park et al. 2000; Spoth et al. 2001). Although several family-based HIV prevention programs have emerged over the past decade, to our knowledge, no universal or selective family focused prevention efforts designed to deter HIV-related behaviors among rural African Americans have been evaluated using randomized, longitudinal design.

Conceptual Model Guiding SAAF

SAAF is based on a developmental model of processes through which program participation is hypothesized to protect rural African American youths from engaging in HIV-related risk behaviors, including early sexual debut and the initiation and escalation of alcohol and substance use (see Fig. 1). Findings from the developers’ research program identified a cluster of protective parenting processes for rural African American youths, characterized as regulated-communicative parenting, which were targeted in the SAAF program. This cluster of protective parenting processes includes involved vigilant parenting, characterized by limit setting, monitoring, racial socialization, inductive discipline, as well as general communication, and clear expectations about sexual behavior and alcohol and substance use. The program also includes prevention experiences for youths, which we hypothesized would enhance youths’ development of self-pride, including racial pride and positive body image. We hypothesized that participating in SAAF would reduce rural African American youths’ engagement in HIV-related risk behaviors over time through the intervention effect on regulated-communicative parenting and youth self-pride. Finally, we proposed that programmatic effects on youth self-pride would foster the promotion of sexual norms and values that would encourage youth to resist engaging in HIV-related risk behaviors.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model

Supportive Evidence from SAAF Efficacy Trials

A recent research report (Brody et al. 2004) addressed the effects of SAAF on posttest changes in intervention-targeted youth and parental behavior. Consistent with the hypotheses that guided the SAAF program’s development, rural African American families who participated in SAAF displayed increases in both regulated-communicative parenting practices and youth protective processes, whereas control families experienced declines in these constructs across the 8 months that separated pretest and posttest. Of particular theoretical importance, intervention-induced changes in regulated-communicative parenting mediated the effect of the intervention on youth protective processes. Brody et al. (2004) found that changing parenting practices produced changes in the proximal youth protective factors that were hypothesized to safeguard African American youths from alcohol use. Further, an evaluation of SAAF effects 27 months post-intervention exposure (Murry et al. 2007) revealed that intervention-induced changes in parenting practices were associated indirectly with reductions in sexual risk behaviors through adolescent self-pride, peer orientation, and sexual intent.

The present research builds on these two prior efficacy studies in three ways. First, we examine the long-term impact of SAAF on HIV-related risk behaviors (e.g., sexual initiation, number of sexual encounters, and condom use during sexual encounters among those who become sexually active) 65 months after pre-test assessment. Second, given that adolescence is a period in which youths’ perceptions about their peers has greater influence on their behavior, we examine the implication of adolescents’ perception of risk engaging agemates as a proxy for their norms and values regarding risk taking. Finally, while peers are important socializing agents during this developmental period, it is simultaneously a period of cognitive growth in which they more concretely internalize the values imparted to them by their parents. Thus, we identify the mechanism through which protective parenting practices reinforce and maintain low-risk behaviors among rural African American youths. Protective parenting practices enhance youths’ racial pride and also influence youths’ norms and values that dissuade risky sexual behavior. In the following section, we review previous literature on parenting practices, as well as youth mediators that explain the relationship between parenting and adolescent sexual outcomes.

Protective Nature of Rural African American Parenting Practices

Universal and Racially-Specific Parenting

The protective capacities of rural African American families are encapsulated in parenting processes that include both universal (i.e., important for all racial/ethnic groups) and racially specific (i.e., especially important for African American families to prepare their children for the challenges associate with “growing up Black in America”) strategies. Exposure to these adaptive parenting processes fosters positive development and adjustment, which in turn protects youth from risky behavior engagement (Brody et al. 2004; Murry et al. 2005). Several theoretical explanations have been offered to describe the pathways through which parenting practices affects youths’ development. For example, the social learning theory (Patterson et al. 1989), problem behavior theory (Jessor and Jessor 1977), and various sociological accounts of delinquency propose that disruptions in parental involvement and support, the use of punitive parenting practices, and low levels of parental monitoring compromise development of the prosocial skills and self-regulatory abilities that protect youths from engagement in risk behaviors, including early sexual activity. High levels of monitoring by caregivers, for example, was the strongest predictor of adolescent willingness to avoid both substance use and delinquency behaviors (Fletcher et al. 2004; Kerr and Stattin 2000). Further, parental monitoring and control have been associated with reduced sexual risk taking among low-income rural African American adolescents (DiClemente et al. 2002).

In addition to universal parenting, racial socialization is an important component of parenting that serves a protective function in shaping African American youths’ self-perception and self-evaluation. Unlike parents in racial majority groups, African American parents must teach their children how to manage their lives and interpret their experiences in a society in which both the parents and children are often devalued (Berkel et al. 2009; Murry et al. 2009; Smith and Brookins 1997). Extant research suggests that the most effective approach to racial socialization involves skillfully weaving messages about positive racial identity, self-esteem, and self-worth into moments of intimacy (Smith and Brookins 1997; Stevenson et al. 1996). Adaptive racial socialization simultaneously requires impacting awareness about the realities of racial oppression with an emphasis on ways to achieve success despite these obstacles (Stevenson et al. 1996).

Parent-Adolescent Communication Patterns

Parents serve as important socializing agents who transmit attitudes, values, and norms regarding behavior to their children and adolescents (Jaccard and Dittus 2000; Jaccard et al. 1998; Whitaker and Miller 2000). In their studies of rural African American youth, Murry and colleagues (2005) found that frequent parent–child conversations about risk engagement provide a forum for rural African American parents to set clear expectations for children’s behavior, including discussions about sexuality and sexual behaviors (Murry et al. 2005). A warm and responsive parent–child relationship increases the likelihood that youths will internalize their parents’ norms and expectations to guide their behavior, and will, in turn, decrease rural African American youths’ reliance on peers’ value systems (Brody et al. 2000; Murry et al. 2009; Whitaker and Miller 2000). Parent-youth communication about sexual issues also provides an avenue to transmit messages and establish expectations about risk engagement. Studies of parent-youth communication about risk have primarily focused on mother-daughter conversations. Based on those studies, it has been shown that girls who reported talking with their mothers regularly about sexual topics held more conservative sexual norms and values, and were more likely to delay sexual debut (Jaccard and Dittus 2000). The extent to which conversations between parents and youths are emotionally and instrumentally supportive appears to be important in buffering African American adolescents against precocious sexual activity (Murry 1996; Wills et al. 1996, 2004). In addition, youths who believe that their parents will listen to them without criticizing them tend to engage in more discussions with their parents (Brody et al. 1998). These discussions may include questions about sexuality and sexual behavior. Moreover, positive, supportive conversations between parents and their children appear to foster self-pride and self-image among youths (Crosby et al. 2003). Further, harmonious parent–child communication buffers youths against negative peer influences (Brody et al. 1998, 2000), and shapes youths’ images of sexually active peers (Gibbons and Gerrard 1997). In addition to these universal parenting practices, rural African American parents also use strategies that are specially geared toward preparing their children for the challenges associate race-related issues, racial socialization.

Protective Nature of African American Youths’ Self-Pride

The factors targeted in SAAF that were posited to confer protection on rural African American adolescents across time have been linked, both theoretically and empirically, with other high-risk behaviors (Petraitis et al. 1995). As illustrated in the conceptual model (Fig. 1), we posited that youth self-pride, which includes positive racial pride and body image, would protect youths from engaging in risky sexual behavior through the impact on internalization of sexual norms and values. These sexual norms and values included youths’ attitudes regarding early sexual activity and images or prototypes of sex initiating peers. In the following paragraph, we review previous literature on racial identity, perception of body image, and their association with sexual norms and values to explain their relationship with sexual outcomes.

Buffering Effects of Positive Self-Evaluation

Developmental theory would contend that to fully understand sexual risk behaviors among African American adolescents, consideration must be given to the influence of culture and racial identity (Faryna and Morales 2000). In that regard, elevated racial identity has been associated with decreased sexual risk taking and increased condom use efficacy among late adolescents and emerging adult African American females (Stokes 2005). Racial identity also has been associated with less alcohol and drug use among adolescents (Caldwell et al. 2004). Although it remains unclear how youths develop a sense of self as African Americans, parents’ childrearing processes, in particular racial socialization, apparently buffer youths from internalizing negative race-related messages (Murry 2000; Stevenson et al. 1996). Moreover, studies of rural African American youths have shown that those who receive explicit messages about race related issues are likely to reject stereotypic images of their race and to develop high sense of racial pride (Smith and Brookins 1997; Murry et al. 2005). Positive racial identity also has been shown to prevent negative body image among African American adolescents (Hess-Biber et al. 2004).

Although research studies examining body image and self-evaluation among African American youths are rare (Cohane and Pope 2001), it is commonly reported that negative body image is a widespread phenomenon among adolescents (Cash et al. 1986). Negative body image, however, appears to be more common among female than male youths. In the current study, we include body image as one of the domains of self pride to capture the rapid physical changes that occur during adolescence, which can lead African American youths to engage in intense evaluations of their bodies in the context of phenotypic features. Though rare, some studies have reported that being African American appears prevent the development of disordered body image (e.g., Hess-Biber et al. 2004). Thus, while African American adolescents absorb some components of the dominant White culture, it appears that they are less likely to accept White standards of weight and beauty.

We provide a plausible explanation of this phenomenon, by suggesting that as African American parents socialize their children to embrace their cultural and historical heritage, including recognition of the importance taking pride in being African American, they may also convey messages about self-acceptances with regard to physical appearance. Family discussions about race, therefore, may render opportunities to talk about taking pride in their physical features, which have had historical significance for the evaluation of attractiveness among African Americans (Harrison and Stonner 1976).

Linking Sexual Norms and Risk Prototypes to Sexual Risk

Research on social image has shown that individuals adopt behavior similar to that of others whom they admire as a means of associating themselves with the positive images they hold (Blanton et al. 1997). Gibbons and Gerrard (1997) reported that favorable attitudes toward peers who engage in high-risk behavior increase rural African American youths’ willingness to engage in such behavior should the opportunity arise. Thus, positive attitudes toward sexually active agemates may augment adolescents’ own sexual intentions and in turn increase their willingness to engage in risky behaviors. Further, adolescents’ evaluations of themselves and their belief systems as “normal,” “appropriate,” and “acceptable” are influenced by social comparisons with peers (Coleman 1980). On the other hand, those youths whose parents engaged in conversations that fostered a sense of pride and conveyed values that emphasized safe and cautious behaviors may be resistant to the negative influence of peers.

The studies included in our review provided a conceptual framework to inform our study hypotheses. We hypothesized that, compared to control group families; families participating in the SAAF intervention would demonstrate higher levels of targeted parenting behaviors, as indicated by mothers’ reports of regulated, communicative parenting, which would in turn promote increases in youth self-pride. We further proposed that youth self-pride would yield greater representation of the internalization of parental sexual norms (i.e., norms to dissuade sexual risk engagement), which would be linked over time (65 months that separated pre-test and long-term follow–up) to delayed sexual initiation, low frequency of sexual encounters, and consistent condom use during sexual encounters among those who become sexually active.

Methods

Participants

Participants in the study were African American mothers and their 11-year-old children (M = 11.2 years of age), who resided in nine rural counties in Georgia. In these counties, families live in small towns and communities in which poverty rates are among the highest in the nation and unemployment rates are above the national average (Dalaker 2001). Although the primary caregivers in the sample work an average of 39.4 h per week, 46.3% of the participants live below federal poverty standards and another 50.4% live within 150% of the poverty threshold. These families are representative of the area in which they live (Boatright 2003); they are best described as working poor.

Of the nine counties from which families were recruited, two were small and contiguous; they were also similar in per capita income and percentage of the population that was African American. These counties were combined into a single population unit, yielding a total of eight countyunits. The eight county-units were randomly assigned to either the control or the intervention condition, resulting in the assignment of four county-units to each condition. Schools in these units provided lists of 11-year-old students, from which 521 families were selected randomly. Of these families, 332 completed pretests. Refusal rates were similar across the intervention and control counties. The recruitment rate of 64% exceeds rates commonly reported for prevention trials that address problematic and high-risk behaviors among children and adolescents (Spoth et al. 1998). The participants included 150 families in the control counties and 172 families in the intervention counties. Families from intervention counties were oversampled to insure that at least 170 families would participate in SAAF. The pretest (n = 332), posttest (n = 319), and at both 27 (n = 311) and 65 (n = 306) long-term follow-ups were completed by, on average, 95% of the families. This retention rate exceeds those reported for other longitudinal-youth risk behavior prevention studies (Forehand et al. 2007; Lochman and van den Steenhoven 2002). To preserve the random nature of the group assignments, the analyses included all families from intervention counties who completed the pretest regardless of the number of sessions that they actually attended (an intent-to-treat analysis). This includes 24 primary caregivers and 22 youths who did not attend any prevention sessions but who completed the pretest, the 3-month posttest, and the 27 and 65 long-term follow-ups. Although this may have reduced the magnitude of the differences between the prevention and control groups, excluding these families would have introduced self-selection bias into the findings. To evaluate differential attrition across experimental conditions, two-factor multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) were conducted with the intervention and control groups for each intervention-targeted behavior, demographic characteristic, and outcome measure. No significant Condition × Attrition interaction effects emerged for any of the variables.

The families had an average of 2.7 children. In 53.6% of these families, the target child was a girl. Of the mothers in the families, 33.1% were single, 23.0% were married and living with their husbands, 33.9% were married but separated from their husbands, and 7.0% were living with partners to whom they were not married. Of the two-parent families, 93.0% included both of the target child’s biological parents. The mothers’ mean age was 38.1 years, and the fathers were an average of 39.4 years old. A majority of the mothers (78.7%) had completed high school. The families’ median household income was $1,655.00 per month.

Procedures

The families were contacted initially by Center staff, with follow-up contacts made by community liaisons, residing in the participating counties and maintaining connections between the University research group and the communities. The community liaisons were African American community members selected on the basis of their social contacts and standing in the community. The community liaisons sent a letter to the families and followed up on the letter with phone calls to the primary caregivers. Families were initially recruited into the overall project but were informed that they could be assigned to an intervention condition. During the phone conversation, the community liaison provided information about the pretest assessment and answered any questions that the caregivers asked. Families who were willing to participate in the pretest were told that a staff member from the University would contact them to schedule the administration of the pretest assessment in the family’s home. Each family was paid $100 at each of the four assessments. Monetary incentives have been found to be important to keeping families engaged in longitudinal studies (Capaldi and Patterson 1987; Guyll et al. 2003). The importance of recognizing the time and effort that families render to participate in research studies have been validated anecdotally by rural African American families who have participated in our previous studies (Murry and Brody 2004).

To enhance rapport and cultural understanding, African American students and community members served as home visitors to collect data for each wave of data, including pre-, post-, and 27 and 65 month follow-up assessments. Prior to data collection, the interviewers received 27 h of training in administering the protocol. The instruments and procedures were developed and refined with the help of a focus group of 40 African American community members who were representative of the population from which the sample was drawn. The focus group process has been described elsewhere in detail (Brody and Stoneman 1992).

During data collections, one home visit lasting 2 h was made to each family. The posttest was conducted in both the prevention and control counties approximately 3 months after the end of prevention programming. The time between pretesting and post-testing averaged 7 months; the long-term follow-ups took place an average of 27 and 65 months after the pretest. Informed consent procedures were completed at all data collection points. Mothers consented to their own and their children’s participation in the study, and the children assented to their own participation. At the home visit, self-report questionnaires were administered to mothers and target children in a computer-based, interview format. Each interview was conducted privately, with no other family members present or able to overhear the conversation. The researchers did not evaluate the mothers’ or children’s ability to read; presenting the questionnaires in an interview format eliminated literacy concerns.

Intervention Development and Implementation

SAAF is based on Brody and Murry’s research program that specifies pathways to competence and adjustment for rural African American children and adolescents living in single-parent and married-parent families. This research was described earlier in the introduction. SAAF is also informed Gibbons and Gerrard’s social psychological model of youth health risk behaviors, and a body of research on the development and evaluation of universal family-strengthening programs (Molgaard and Spoth 2001; Spoth and Redmond 2000). SAAF targets enhancement of family protective processes to strengthen factors that protect youths from engaging in high-risk behaviors. The SAAF prevention program consists of seven consecutive weekly meetings held at community facilities. Each of the seven meetings includes separate, concurrent training sessions for parents and children, followed by a joint parent– child session during which the families practice the skills they learned in their separate sessions. Each concurrent and family session lasts 1 h. Thus, parents and youths receive 14 h of prevention training. At the same times that the intervention families participate in the seven prevention sessions, the control families receive three leaflets via postal mail; one describes various aspects of development in early adolescence, another one addresses stress management, and the other provides suggestions for encouraging children to exercise.

Parents in the prevention condition are taught regulated, communicative parenting, including the use of consistent discipline, monitoring, and involvement, adaptive racial socialization strategies, strategies for communication about sex, and the establishment of clear expectations about alcohol use and sexual risk. Youth learn the importance of having and abiding by household rules, adaptive behaviors to use when encountering racism, the importance of forming goals for the future and making plans to attain them, the similarities and differences between themselves and their sexually active, substance using peers, realistic estimates of the prevalence of alcohol and other substance use, and resistance efficacy strategies. Together, family members practice communication skills and engage in activities designed to increase family cohesion and the youth’s positive involvement in the family.

Ten three-person teams delivered the 7-session program to 19 groups in the prevention counties. Group leader application materials were reviewed and interviews were conducted to select applicants with the strongest interpersonal and group facilitation skills. All group leaders were African American. The selected leaders participated in three training sessions over a period of 4 days. Before conducting any intervention sessions, group leaders demonstrated their mastery of selected prevention material and the prescribed method of presenting it. Each parent group had one leader who presented the prevention curriculum, guided discussions among group members, and answered participants’ questions. Each youth group had two leaders who presented the prevention curriculum, organized roleplaying activities, guided activities and discussions, and answered participants’ questions. Program content for the parents’ sessions was also delivered by video. The narrators of the videos were prominent members of the communities and parents from the communities acted out role-plays depicting the targeted behaviors. Videotapes were also used in three youth sessions, showing older teens discussing typical high-risk situations and ways of dealing with temptation and peer pressure. These videos also feature a nationally-known African American movie actor. Fewer videotapes were used in the youths’ sessions than in the parents’ sessions because some of the topics presented to the youths could be addressed better through targeted activities.

Families who were assigned randomly to the prevention condition participated in the 19 groups. Group sizes ranged from 3 to 12 families, with an average group size of 10 families and an average of 20 individuals attending each session. Approximately 65% of the pre-tested families took part in five or more sessions, with 44% attending all seven of them. Each team of group leaders was videotaped while conducting intervention sessions to assess fidelity to the prevention program. For each group, two parent, two youth, and two family sessions were selected randomly and scored for adherence and coverage of the prevention curriculum. Coverage of the components that comprised the prevention curriculum exceeded .80 for the primary caregiver, target, and family sessions. Reliability checks were conducted on 23% of the fidelity assessments and exceeded .80 for each of the three types of sessions.

Measures

The measures for the SAAF study were selected for their relevance in evaluating the SAAF program. Many of the measures were derived from previous studies of African American families (Wills et al. 2000) and of parenting and risk perceptions among rural adolescents (Gibbons and Gerrard 1995). Several measures of relevant constructs that were added for the present study received preliminary testing in focus groups of community respondents (Brody et al. 2004; Murry and Brody 2004). Four waves of data have been collected, including pre-test assessment; 3-month post-test assessment, 27-month long-term follow up; and 65-month long-term follow up. For the current study, we utilized three waves of data: pre, post- and 65-month, long-term, follow-up. Our study was specifically designed to examine the sustainability of SAAF as youth transitioned into late adolescence. The decision to exclude the 27 month follow up assessment in our analyses was based on the fact that participants were relatively young, on average age 13.5 years, and less the incidence of sexually activity was extremely low; only 1% had become sexually active.

Regulated, Communicative Parenting

Four indicators were used to assess regulated, communicative parenting. Two indicators, involved-vigilant parenting and adaptive racial socialization, pertained to caregivers’ parenting behaviors. The other two indicators, general communication patterns and specific communication about sex, dealt with aspects of the interactional patterns in the home environment. A description of each of the four indicators is provided in the following section.

Involved-Vigilant Parenting

Involved-vigilant parenting was assessed using an instrument that we have included in our previous research with rural African American families (Brody et al. 2004, 2001). The measure is composed of 19 items, rated on a scale that indexes the frequency, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), of parental behaviors related to involvement, inductive discipline, consistent discipline, and monitoring. Nine items addressed involvement and inductive discipline (e.g., “When you and your child have a problem, how often can the two of you figure out how to deal with it?,” “When your child doesn’t know why you make certain rules, how often do you explain the reason?”); five items concerned child monitoring (e.g., “How often do you know where your child is when he or she is away from home?”); and four items assessed consistent discipline (e.g., “How often do you discipline this child for something at one time and at other times not discipline him or her for the same thing?”). As in our prior research (Brody et al. 2004, 2001), responses to these subscales were summed to form the involved-vigilant indicator. Cronbach’s alphas at both waves of data collection exceeded .70.

Adaptive Racial Socialization

Adaptive racial socialization was assessed via the Racial Socialization Scale (Hughes and Johnson 2001), which includes 15 items, rated on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 3 (three to five times), concerning the frequency with which parents engaged in specific racial socialization behaviors during the past month. These behaviors included talking with children about the possibility that some people might treat them badly or unfairly because of their race, talking to children about important people or events in African American history, and doing or saying things to encourage children to learn more about African American history or traditions. Cronbach’s alphas at both waves exceeded .75.

General Communication

General communication patterns were evaluated using three items, coded on a scale ranging from 0 (I usually do most of the talking) to 3 (We usually talk about it openly and share our sides of the issue), to assess the degree of openness in family communications. A sample item is, “When you and your child talk about his/her choice of friends, how does the conversation go?” Cronbach’s alphas were .62 at Wave 1 and .68 at Wave 2.

Parental-Child Communication About Sex

Caregivers’ communication with their children about sexual issues was assessed using a modified version of the parental communication about substance use (see Gerrard et al. 2003). The measure includes nine items, coded on a scale ranging from 0 (no) to 2 (yes, quite a bit), in which parents were asked whether they had ever talked to their child about topics such as reproduction/having babies, menstruation, sexually transmitted diseases, and HIV/ AIDS. Cronbach’s alphas were .82 at Wave 1 and Wave 2.

Youths’ Self-Pride

Two measures were used to assess youth self-pride, racial pride and body image. The three-item Black Pride scale was used to assess racial pride. The items, which are rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), are “Being Black is an important part of my self-image,” “I often regret that I am Black” (reverse scored), and “I believe that, because I am Black, I have many strengths.” Cronbach’s alphas were .65 at Wave 1 and .67 at Wave 2. The Body Image subscale from the Sexual Self-Concept Inventory (Palmer and Murry 2000) consists of eight items that index youths’ evaluations of their own physical appearance. Sample items include, “I like the way my body looks,” “I do not need to change the way my body looks,” and “I feel I am too fat or overweight.” The subscale’s response set ranges from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 4 (describes me very well). Cronbach’s alphas were .57 at Wave 1 and .58 at Wave 2.

Sexual Norms and Prototypes

The sexual norms and prototypes scale, developed from Gerrard and associates’ (2003) Risk Prototype Scale, was used to assess the origins of youths’ sexual norms and images of sexually engaged youth. We selected two items to be used in developing a composite score that reflects internalization of parental expectations and norms regarding sexual engagement. Youths were asked to indicate the extent to which their beliefs and attitudes regarding sexual behavior were based on those of their parents: “How much would your parents’ values influence whether or not you decide to have sex?” and “How much would being concern about your reputation influence whether or not to you decide to have sex?” The response set ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Cronbach’s alphas were .67 for Wave 1 and .75 for Wave 2. The second item, “concerns about reputation,” was based on reputation enhancement and goal setting theories (Carroll et al. 2001). We expect high scores on this item to reflect more conventional norms about early sexual initiation, in which youths expect early sexual involvement to compromise rather than enhance their reputations. We also derived from prior research on prototypes (Gibbons and Gerrard 1995) a measure of youths’ cognitive images of peers who were or were not sexually active. Using a response set ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very), youths indicated how popular, selfish, smart, cool, unattractive, and dull they considered sexual engagers and sexual abstainers to be. We coded the items so that high scores reflected positive evaluations. Cronbach’s alphas were .77 at Wave 1 and .73 at Wave 2 for prototypes of sexual engagers and .81 at both waves for prototypes of sexual abstainers.

Sexual Risk Behavior

A sexual risk composite index was formed to assess SAAF’s efficacy on youth sexual behavior patterns. The index consisted of three items, one in which youths were asked (a) if they had ever had sex, defined as vaginal/penile penetration, (b) if they had ever had sex, how frequently did they have sex during the past month, and (c) if they had ever had sex, did they use a condom. All items were scored 1 for affirmative and 0 for negative responses; the responses were summed, yielding a scale with a possible range of 0–3. The αs across the three waves of data collection was .70.

Results

Plan of Analysis

Participation in the SAAF program was a dummy coded variable. Thus, participants randomly assigned to the program were coded as 1 and those assigned to the control group were coded 0. The hypothetical model presented in Fig. 1 was analyzed via structural equation modeling (SEM) using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation method. FIML does not delete cases for which data are missing from one or more waves of data collection, nor does it delete cases for which data are missing for a variable within a wave of data collection. This method thus avoids potential problems, such as biased parameter estimates, that are more likely to occur if pairwise or list-wise deletion procedures are used to compensate for missing data (Arbuckle and Wothke 1999). Table 1 presents the correlation matrix, means, and standard deviations for the SEM variables; Fig. 2 presents the results of the test of the structural model.

Table 1.

Intercorrelations, means, and standard deviations for all study variables

| Study variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulated, communicative parenting, W1 | ||||||||||

| 1. Involved, vigilant parenting | – | |||||||||

| 2. Racial socialization | .22 | – | ||||||||

| 3. Sexuality communication | .28 | .16 | – | |||||||

| 4. General communication | .40 | .18 | .34 | – | ||||||

| Preadolescent self-pride, W1 | ||||||||||

| 5. Racial pride | .06 | .15 | .11 | .08 | – | |||||

| 6. Body image | .04 | .14 | −.03 | .01 | .33 | – | ||||

| Sexual norms, W1 | ||||||||||

| 7. Personal values about sex | .00 | .03 | .10 | .03 | .21 | .14 | – | |||

| 8. Prototype of sexually active peers | −.11 | −.09 | −.07 | −.09 | −.17 | −.17 | −.17 | – | ||

| 9. Prototype of non-sexually-active peers | .08 | .08 | .09 | .06 | .30 | .19 | .21 | −.35 | – | |

| 10. Sexual risk index, W1 | −.17 | −.05 | .01 | .04 | −.05 | −.07 | .00 | .18 | −.07 | – |

| Regulated, communicative parenting, W2 | ||||||||||

| 11. Involved, vigilant parenting | .59 | .19 | .25 | .33 | −.01 | .01 | .02 | −.15 | .14 | .08 |

| 12. Racial socialization | .18 | .49 | .10 | .16 | .10 | −.03 | −.03 | −.06 | .06 | .03 |

| 13. Sexuality communication | .20 | .01 | .43 | .17 | .07 | −.03 | .05 | .06 | .05 | .00 |

| 14. General communication | .35 | .15 | .23 | .49 | .11 | .04 | .11 | −.15 | .09 | −.02 |

| Preadolescent self-pride, W2 | ||||||||||

| 15. Racial pride | .15 | .09 | .14 | −.01 | .30 | .11 | .19 | −.08 | .15 | −.10 |

| 16. Body image | .11 | .15 | .08 | .07 | .20 | .34 | .10 | −.04 | .18 | −.03 |

| Sexual norms, W2 | ||||||||||

| 17. Personal values about sex | −.00 | −.00 | .09 | .04 | .09 | .05 | .18 | −.02 | .09 | −.03 |

| 18. Prototype of sexually active peers | −.06 | −.02 | −.14 | −.03 | .05 | −.07 | −.08 | .34 | −.15 | .12 |

| 19. Prototype of non-sexual active peers | .04 | −.03 | .05 | .09 | .15 | .07 | .22 | −.22 | .22 | −.06 |

| 20. Sexual risk index, W6 | .01 | −.06 | .00 | .00 | .04 | .00 | .07 | .10 | −.07 | .08 |

| M | 28.35 | 23.76 | 37.61 | 7.59 | 57.87 | 46.72 | 6.39 | 11.94 | 25.55 | .02 |

| SD | 4.41 | 5.50 | 6.29 | 3.20 | 6.85 | 6.55 | 3.03 | 5.45 | 5.48 | .17 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Study variables | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Regulated, communicative parenting, W1 | ||||||||||

| 1. Involved, vigilant parenting | ||||||||||

| 2. Racial socialization | ||||||||||

| 3. Sexuality communication | ||||||||||

| 4. General communication | ||||||||||

| Preadolescent self-pride, W1 | ||||||||||

| 5. Racial pride | ||||||||||

| 6. Body image | ||||||||||

| Sexual norms, W1 | ||||||||||

| 7. Personal values about sex | ||||||||||

| 8. Prototype of sexually active peers | ||||||||||

| 9. Prototype of non-sexually-active peers | ||||||||||

| 10. Sexual risk index, W1 | ||||||||||

| Regulated, communicative parenting, W2 | ||||||||||

| 11. Involved, vigilant parenting | – | |||||||||

| 12. Racial socialization | .26 | – | ||||||||

| 13. Sexuality communication | .31 | .17 | – | |||||||

| 14. General communication | .49 | .15 | .34 | – | ||||||

| Preadolescent self-pride, W2 | ||||||||||

| 15. Racial pride | .11 | .12 | .05 | .12 | – | |||||

| 16. Body image | .11 | .14 | .04 | .08 | .38 | – | ||||

| Sexual norms, W2 | ||||||||||

| 17. Personal values about sex | .03 | −.02 | .00 | .12 | .26 | .22 | – | |||

| 18. Prototype of sexually active peers | −.16 | −.06 | .04 | −.06 | −.27 | −.26 | .26 | – | ||

| 19. Prototype of non-sexual active peers | .10 | −.00 | .05 | .08 | .15 | .17 | −.18 | −.30 | – | |

| 20. Sexual risk index, W6 | −.03 | −.03 | .05 | .00 | −.10 | −.06 | −.07 | .19 | −.02 | |

| M | 28.42 | 24.93 | 39.73 | 8.16 | 59.63 | 47.14 | 7.13 | 12.62 | 1.00 | |

| SD | 4.72 | 5.74 | 6.72 | 2.95 | 6.76 | 6.03 | 2.95 | 5.43 | 0.98 | |

All correlations greater than .12 are significant at p <.05

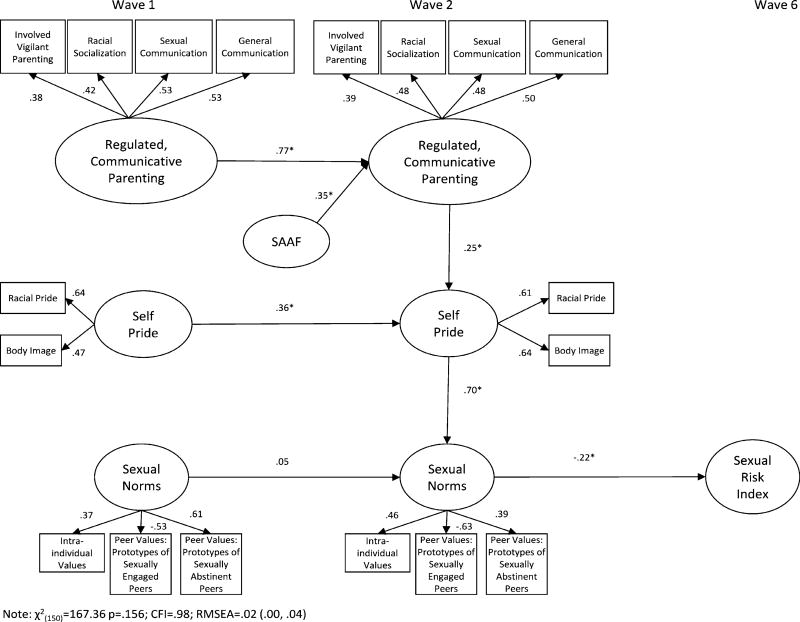

Fig. 2.

Empirical model

Group Equivalence

Before conducting the outcome analyses, family sociodemographic characteristics (i.e., primary caregiver education and age, number of children in the household and per capita income) and all study variables were examined for equivalence across prevention and control groups. A hierarchical linear model was used to determine pretest equivalence because participants were nested in counties (Bryk and Raudenbush 1992). The means and t values for the family sociodemographic variables at pretest indicated that the data were equivalent across the prevention and control conditions. One measure, parent–child communication about sex, was not equivalent at pretest; scores were higher in the control group. All pretest scores were controlled in the analyses of study hypotheses (Aiken et al. 1994).

Clustering Effects

In the current study, intervention and control group assignments were made at the county level. As a result, prior to conducting SEM analyses, we conducted intraclass correlations for all study variables to assess possible county level effects. No intraclass correlation exceeded .05, indicating that analyses conducted at the individual level were not statistically biased (Heck 2001). Accordingly, the analyses used to test the study hypotheses were conducted at the individual level.

Test of Prevention Effects

SEM was used to test the distal mediational hypothesis that intervention-induced changes in parenting would predict changes in adolescent racial pride and body image, which would be associated over time with sexual norms and the sexual risk index. Table 1 presents the correlations, means, and standard deviations for all study variables. To measure the effect size of SAAF on posttest targeted parenting practices, we calculated Cohen’s d to be .49 (.50 is considered a medium effect size; Cohen 1988). Because of the length of time between the program and the long-term follow-up, detecting a substantial effect size on sexual behavior was unlikely with a sample size of under 1000 (Cohen 1988); as expected it was .01. The full hypothetical model (see Fig. 1) was analyzed using Mplus 6.0 software (Muthén and Muthén 2010).

First, we tested the measurement model for each latent construct separately. We included the latent construct from two time points in the measurement model and intercor-related the latent variables. We also correlated the indicators across two time points to reflect the nature of the repeated measures. All the measurement models evaluated fit the data well and the indicators had reasonable loadings (≥.30) onto the latent constructs. We then combined all the constructs in the model to test the hypothesized relationships presented in the heuristic model. In this model, we correlated the error terms of the same indicators measured at two time points. We also intercorrelated the exogenous latent constructs in the model presented in Fig. 2.

Overall, the model fit the data well: χ2 (df = 150, p = .156) = 167.37; χ2/df = 1.18. The following fit indices also supported adequate model fit: CFI = .99; RMSEA = .02 (90% CI .00, .04). All indicators loaded significantly on their latent constructs, supporting measurement adequacy (see Fig. 2). The standardized Bs represent tests of hypotheses about the relations among theoretical constructs and supported the distal mediational hypotheses. Participation in SAAF led to an increase in the use of intervention-targeted parenting practices (β = .35, p < .01), with pretest levels of parenting practices controlled. This increase in parenting practices, in turn, was associated with an increase in youths’ self- pride (β = .25, p < .05), with pretest levels controlled. Self-pride was in turn associated with increases in protective sexual norms (β = .70, p < .01), which in turn, protected against engagement in sexual risk behavior (β = −.22, p < .01). Thus, consistent with the distal mediational hypotheses, program-induced changes in parenting led to an increase in youths’ racial pride and body image, which was associated with protective norms and behavior at the 65 month follow-up. Incidentally, while parenting, and to some extent, self pride, were relatively stable over time, sexual norms at Wave 1 were completely uncorrelated with sexual norms at Wave 2. This suggests a period of rapid change, due in part to the positive influences of parenting and subsequent increases in youth self pride.

To further probe the analyses, we examined the moderational effect of gender using multiple-group comparisons in SEM. We first freed all the parameters across genders and then fixed one parameter at a time to see if the model fit was significantly different in terms of chi-square change. The result indicated no significant difference between genders on any paths in the model. Thus, this suggests that SAAF intervention effects were similar for late adolescent females and males in reducing risky sexual behavior.

Discussion

The growing prevalence of HIV/AIDS among African American youths is one of the most critical issues confronting African American communities in the rural South. To our knowledge, SAAF is the first universal, family-focused preventive intervention designed specifically for rural African Americans with the overall goal of understanding and supporting the ways in which parents promote youths’ health and dissuade risk behavior. Although some family-focused interventions for African American youths have been developed and disseminated, few have been rigorously evaluated using randomized, controlled research designs with African American populations (Center for Substance Abuse Prevention 2006). This report, then, is the first to present a randomized, controlled trial of a family-centered intervention designed to deter sexual risk behavior among rural African American youth as they transition from middle childhood through late adolescence.

In the current study, we sought to examine the influence of participation in SAAF on sexual risk behaviors in a sample of rural African American youth, who were assessed four times from ages 11–17 years. The participants were relatively young and the number of sexually active youth was initially low at pre-test and remained relatively low in absolute terms, at our 27 months after the pre-test data collection. Given this, we examined SAAF’s efficacy in preventing sexual risk engagement among rural African American late adolescence with data collected at 65 months after the pre-test. Targeting the parenting of early adolescents in reducing sexual risk behavior and tracking the impact over time is important for many reasons. Primarily, because an increasing number of African American youths are becoming sexually active during early adolescence (CDC 2006; DiClemente and Wingood 1995), preventing the transition to early sexual risk behavior has been more effective than limiting such behavior once it has started. Second, family-based programs targeting parenting are an extremely promising intervention strategy for young people given the prominence of the family’s role in development. This is especially the case within the African American culture, whose traditional values emphasize the primacy of the family (Murry et al. 2011). Internalization of norms to guide behavior that are transmitted from parent to child is a developmental process. Parents’ socialization efforts with their early adolescent children can take years to produce visible effects in terms of the reduction of risk behaviors.

It is noteworthy that the current study design allowed for the testing of a theory emerging from over a decade of research on rural African American families, on which the program is based (Brody et al. 2004; Murry and Brody 2004; Cicchetti and Toth 1992; Dishion and Patterson 1999). Our findings revealed that compared with parents in the control condition, parents participating in the SAAF intervention demonstrated higher levels of intervention-targeted parenting behaviors, as indicated by mothers’ reports of both universally-adaptive parenting, as well as racially specific socialization processes. In addition, compared to the adolescents in the control conditions, fewer SAAF youth at age 17 years had ever had sex, and those who had become sexually active reported fewer sexual encounters, and greater likelihood of using condoms during sexual encounters. The primary contribution of this report is an illustration of the developmental process by which this occurred.

SAAF’s efficacy can be attributed to several factors, the most important of which is the research base that guided its development. SAAF was envisioned and designed using an approach that is consistent with recommendations presented in reports issued by the Institute of Medicine (1994) and the National Institute of Mental Health (1998). Both agencies emphasized the importance of basing an intervention’s theoretical model on research conducted with populations similar to those who will receive the intervention. SAAF was based on over a decade of longitudinal, developmental studies with rural African American families. These studies led to the development of standing partnerships with community stakeholders, who live in the community and are well-known and respected by members of the community (Murry and Brody 2004). This community research engagement approach facilitated the development of the SAAF program for rural African Americans to prevent HIV/AIDS vulnerability among youth, a need mutually recognized by researchers and community members. The findings presented here support the tenets of the theoretical models guiding the SAAF program, and in turn, our study, illustrating how general and racially-specific parenting processes of rural African Americans are geared toward enhancing resilience among their children.

Our findings corroborate previous studies demonstrating that parenting practices of African Americans do, indeed, serve as a protective factor for youth, and thereby reduce youths’ vulnerability to risky sexual behavior. The process by which African American parents influence youths’ development, in particular self-acceptance and self-pride, may be informed by Lerner’s (1987) circular functioning theory. This theory posits that during the early years of children’s development, they receive feedback from others, including parents, about their appearances. This interaction triggers children’s self-evaluation. Children develop greater self-acceptance when these interactions are positive and fit with the prevailing standards of persons who are important to the youths. Moreover, African American youths are less likely to internalize negative self-images when their parents skillfully weave messages about self-esteem and self-worth into moments of supportive parent– child conversations (Smith and Brookins 1997; Stevenson 1996).

Harmonious parent–child communication not only buffers youths from negative peer influences but also increases the likelihood that youths will internalize their parents’ norms and expectations regarding acceptable behavior, including ways to avoid and resist engagement in risk behaviors (Brody et al. 1998, 2000). Such conversations also encourage youth to seek information from their parents about potentially high-risk situations (Kotchick and Forehand 2002). We observed increases in parent-youth conversations about expectations regarding risk engagement, which in turn fostered protective sexual norms regarding reasons to delay sexual debut.

Our findings also contribute to those studies showing significant links between heightened parental monitoring and diminished sexual risk behavior among adolescents (DiClemente et al. 2001). Parents may indirectly influence youth risk behavior through their monitoring activities by screening adolescents’ peer affiliations. Evidence of this peer screening process may transmit norms and expectations regarding acceptable behaviors for youth. Youth participating in the SAAF program has less favorable images of sexually active agemates (Gibbons et al. 2003). Taken together, our findings offer support for the importance of identifying the processes through which youths’ self-perception and sexual norms are linked to decisions about engaging in sexual risk behaviors.

Our final analyses test for potential gender effects in the hypothetical model’s predicted pathways. The results revealed that the links from youth sexual norms and sexual risk were similar for both female and male rural African Americans during late adolescent. Most studies examining the impact of parenting on adolescent sexual risk have focused on the age of sexual debut and pregnancy among female adolescents. SAAF is the only randomized prevention trial designed to avert sexual risk engagement among rural African American sons and daughters. Thus, findings from our study illustrate that the contributions of the SAAF program on the intervention-targeted parenting was effective in dissuading sexual risk engagement for both genders.

We acknowledge that our study is not without limitations. First, it is important to recognize the heterogeneity of both African American families and rural families. The extent to which our findings can be generalized to rural African American families from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds remains unknown. Further, we would caution against implementing this program with non-rural adolescents without careful adaptation processes involving the targeted communities, as metro status has important contributions to family needs and values (Kogan et al. 2006). In addition, our procedures did not control for several contributing factors that are known to affect sexual behavior, such as family structure, neighborhood characteristics, and family income. Finally, the ultimate target of sexual risk programs must be a reduction in the prevalence of HIV/AIDS and other STDs (Barrow et al. 2008). A study to address this goal would require implementation on a much larger scale. Nevertheless, our study provides a clearer understanding of the processes through which SAAF induced changes in parent practices, heightened youth self-pride, instill sexual norms in youth that in turn were associated with reduction in HIV/AIDS vulnerable behaviors.

In sum, the results from our study underscore the powerful effects of parenting practices among rural African American families that over time serve a protective role in reducing youth risk behavior. Highlighted in the current study is the importance of designing a preventive intervention program that is designed and developed guided by theoretical and empirical works emerging from the targeted population (Brody et al. 2002; Murry and Brody 2002, 2004). Further, basic developmental research can illuminate critical periods when protective processes may be especially important and when outcomes may be observed; these may not occur at the same time. This study demonstrates the importance of engaging rural African American parents and pre-adolescents in family-centered interventions to prevent sexual risk behaviors through culturally competent, developmentally appropriate prevention strategies.

Acknowledgments

Velma McBride Murry’s involvement was supported by funding from National Institute of Mental Health, Grant R01MH063043. Cady Berkel’s involvement in the preparation of this manuscript was supported by Training Grant T32MH18387.

Biographies

Velma McBride Murry is an Endowed Chair, Education and Human Development, and Professor of Human and Organizational Development, Peabody College at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee. She received her Ph.D. in Human Development and Family Relations, University of Missouri-Columbia, 1988. She has extensive expertise on adversity that includes race, ethnicity, and poverty; with a background in the role that parenting plays in addressing the needs of rural African American youth. She has completed an efficacy trial, the Strong African American Families (SAAF) Program, designed to enhance parenting and family processes to in turn encourage youth to delay age at sexual onset and the initiation and escalation of alcohol and drug use. Currently, Dr. Murry is implementing a randomized control trial of the Pathways for African American Success Program, a second generation version of the SAAF program, that is designed to test the feasibility and efficacy of delivering a family based randomized prevention trial via computer-based interactive technology. This RCT aims to provide information about the potential of a computer-based versus a group-based intervention to increase the accessibility and diffusion potential of a HIV risk reduction programming for rural African Americans.

Cady Berkel is a Faculty Research Associate at the Prevention Research Center at Arizona State University. She received a Ph.D. in Child and Family Development from the University of Georgia in 2006. Her primary research interests relate to the impact of discrimination on adolescent health and social disparities, and the protective influence of cultural factors. She is also interested in improving interventions that may reduce disparities via research on program implementation, with specific attention to cultural adaptations.

Yi-Fu Chen is a Research Statistician, providing statistical consulting at the Center for Family Research. He obtained his Ph.D. in Sociology with a minor in Statistics from Iowa State University. His research interests are in methodology, mental health, and social deviance. He is especially interested in applying mixture models to studies of adolescent delinquency over the developmental life course and to the relationship between delinquency and affiliation with delinquent peers. He is also interested in cross-cultural studies of adolescent delinquency and peer relationships in the States and Taiwan.

Gene H. Brody is a Regent’s professor at the Department of Child and Family Development, University of Georgia, Athens, GA and Director of the Center for Family Research. His research focuses on the identification of family processes that contribute to academic and socioemotional competence in children and adolescents.

Frederick X. Gibbons is a research professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Dartmouth University. He received his Ph.D. in psychology at the University of Texas, 1976. His primary research focused on the application of social psychological theory to health behavior—substance use, risky sex, sun exposure, vaccinations, and exercise. Most of his research is based on a social-reaction model of adolescent health-risk behavior, the prototype/willingness (PW) model, which contends that, adolescents’ health decision-making strategies are often reactions to risk-conducive situations rather than planned activities.

Meg Gerrard is Professor of Psychiatry and Co-director of the Cancer Control Research Program at the Dartmouth Medical School. She received her Ph.D. in community psychology from the University of Texas with a focus on risky sexual behavior. She established the Health and Behavior Research Project at Iowa State University and became one of the founding members of the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS). One of her primary areas of research over the last several years has been health risk and health promoting factors among African American adolescents and emerging adults. She also studies a variety of other risk behaviors in African American and White adolescents and young adults including risky and unprotected sexual behavior, UV exposure, and health protective behaviors such as HPV vaccination.

Contributor Information

Velma McBride Murry, Peabody College, Vanderbilt University, #90 230 Appleton Place, Nashville, TN 37203-5721, USA.

Cady Berkel, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA.

Yi-fu Chen, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA.

Gene H. Brody, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA

Frederick X. Gibbons, Dartmouth University, Hanover, NH, USA

Meg Gerrard, Dartmouth University, Hanover, NH, USA.

References

- Aiken LS, Stein JA, Bentler PM. Structural equation analyses of clinical subpopulation differences and comparative treatment outcomes: Characterizing the daily lives of drug addicts. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:488–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 user’s guide. Chicago: Small Waters Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow RY, Berkel C, Brooks LC, Groseclose SL, Johnson DB, Valentine JA. Traditional STD prevention and control strategies: Adaptation for African American communities. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35:S30–S39. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818eb923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Murry VM, Hurt TR, Chen Y-f, Brody GH, Simons RL, et al. It takes a village: Protecting rural African American youth in the context of racism. Journal of Adolescent Health Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:175–188. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9346-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton H, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Conger KJ, Smith GE. The role of family and peers in the development of prototypes associated with substance use. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:271–288. [Google Scholar]

- Boatright SR. The Georgia county guide: 2003. Athens, GA: Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z. Child competence and developmental goals among rural Black children: Investigating the links. In: Sigel I, McGillicuddy-DeLisi A, Goodnow J, editors. Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 415–431. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Flor DL, Hollett-Wright N, McCoy JK. Children’s development of alcohol use norms: Contributions of parent and sibling norms, children’s temperaments, and parent-child discussions. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12:209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Katz J, Arias I. A longitudinal analysis of internalization of parental alcohol-use norms and adolescent alcohol use. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4(2):71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger R, Gibbons FX, Murry VM, Gerrard M, et al. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72:1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Kim S, Brown AC. Longitudinal pathways to competence and psychological adjustment among African American children living in rural single-parent households. Child Development. 2002;73:1505–1516. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, et al. The Strong African American Families Program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Bernat DH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, parental support, and alcohol use in a sample of academically at-risk African American high school students. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;34:71–81. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000040147.69287.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Patterson GR. An approach to the problem of recruitment and retention rates for longitudinal research. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll A, Houghton S, Durkin K, Hattie JA. Adolescent reputations at risk: Developmental trajectories to delinquency. NY: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Winstead BA, Janda LH. The great American shape-up: Body image survey report. Psychology Today. 1986;20(4):30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Prevention. Communities untouched by substance abuse and addiction. 2006 Retrieved from http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/

- Centers for Disease Control, Prevention. Racial/ethnic disparities in diagnoses of HIV/AIDS-33 states, 2001–2004. MMWR: Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55:121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. The role of developmental theory in prevention and intervention. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4:489–493. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402004017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohane GH, Pope HG., Jr Body image in boys: A review of the literature. Eating Disorders. 2001;29:373–379. doi: 10.1002/eat.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JC. Friendship and the peer group in adolescence. In: Adelson J, editor. Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley Inc; 1980. pp. 408–431. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Lang DL, Harrington K. Infrequent parental monitoring predicts sexually transmitted infections among low-income African American female adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:169–173. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalaker J. Poverty in the United States, 2000 (U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Reports Series P60–214) Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dee TS. The effects of minimum legal drinking ages on teen childbearing. The Journal of Human Resources. 2001;36:824–838. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. A randomized controlled trial of an HIV sexual risk-reduction intervention for young African-American women. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;274:1271–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby RA, Sionean C, Brown LK, Rothbaum B, et al. A prospective study of psychological distress and sexual risk behavior among black adolescent females. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E85–E90. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.5.e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Sionean C, Crosby RA, Harrington K, Davis S, et al. Association of adolescents’ history of sexually transmitted disease (STD) and their current health high-risk behavior and STD status. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29:503–509. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Kavanagh K. A multilevel approach to family-centered prevention in schools: Process and outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:889–911. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. Model building in developmental psychopathology: A pragmatic approach to understanding and intervention. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:502–512. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2804_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faryna E, Morales E. Self-efficacy and HIV-related risk behaviors among multiethnic adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority. 2000;6:42–56. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.6.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher AC, Seinberg L, Williams-Wheeler M. Parental influences on adolescent problem behavior: Revisiting Stattin and Kerr. Child Development. 2004;75:781–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Armistead L, Long N, Wyckoff SC, Kotchick BA, Whitaker D, et al. Efficacy of a parent-based sexual risk prevention program for African American preadolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161:1123–1129. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Gano M. Adolescents’ risk perceptions and behavioral willingness: Implications for intervention. In: Romer D, editor. Reducing adolescent risk: Toward an integrated approach. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Predicting young adults’ health risk behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:505–517. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Health images and their effects on health behavior. In: Buunk BP, Gibbons FX, editors. Health, coping, and well-being: Perspectives from social comparison theory. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1997. pp. 63–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ. A social-reaction model of adolescent health in risk. In: Suls JM, Wallston KA, editors. Social psychological foundations of health and illness. Oxford, England: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. A developmental analysis of sociodemographic, family, and peer effects on adolescent illicit drug initiation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:838–845. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyll M, Spoth R, Redmond C. The effects of incentives and research requirements on participation rates for a community-based preventive intervention research study. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2003;24:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Li J, McKenna MT. HIV in predominantly rural areas in the United States. Journal of Rural Health. 2005;21:245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison AO, Stonner DM. Reference groups for female attractiveness among Black and White college females. Paper presented at the 3rd Conference on Empirical Research in Black Psychology; Cornell University; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Heck RH. Multilevel modeling with SEM. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2001. pp. 89–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hess-Biber SN, Howling SA, Leavy P, Lovejoy M. Racial identity and the development of body image issues among African American adolescent girls. The Qualitative Report. 2004;9:49–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Johnson D. Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:981–996. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ. Adolescent perceptions of maternal approval of birth control and sexual risk behavior. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1426–1430. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.9.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J, Dittus PJ, Gordon W. Parent-adolescent congruency in reports of adolescent sexual behavior and in communications about sexual behavior. Child Development. 1998;69:247–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestel CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, Ford CA. Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;161:774–780. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M, Stattin H. What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:366–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Berkel C, Chen Y-f, Brody GH, Murry VM. Metro status and African-American adolescents’ risk for substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchick BA, Forehand R. Putting parenting in perspective: A discussion of the contextual factors that shape parenting practices. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2002;11:255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM. A life-span perspective for early adolescence. In: Lerner RM, Foch TT, editors. Biological-psychosocial interactions in early adolescence. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]