Abstract

Objective

As the prevalence of older adults living with HIV disease increases, questions are emerging regarding the extent to which older age amplifies the adverse effects of HIV on employment status and functioning. This cross-sectional study sought to: 1) investigate the combined effects of HIV and older age on employment status, 2) identify clinicodemographic correlates of employment status among older HIV+ persons, and 3) examine the combined effects of HIV and age on workplace performance among employed participants.

Method

The sample was 358 HIV+ (163 Older, 195 Younger) and 193 HIV− (94 Older, 99 Younger) adults, who completed a comprehensive neurocognitive research assessment that included measures of employment status and current workplace functioning.

Results

We observed main effects of HIV and age on employment status, but no interaction. The Older HIV+ sample demonstrated particularly high rates of disability, rather than elective retirement or unemployment. Among older HIV+ adults significant predictors of employment status included age, global neurocognitive functioning, cART status, age at HIV infection, and hepatitis C co-infection.

Finally, self-reported work functioning of Older HIV+ adults differed only from the Younger HIV− group.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that older age and HIV disease have additive adverse effects on employment status, but not work functioning, and that employment status is associated with both neurocognitive and medical risk factors among older HIV+ adults. Further longitudinal research is needed to elucidate specific disease and demographic characteristics that may operate as protective factors for retaining gainful employment among older HIV+ adults.

Keywords: AIDS/HIV, aging, employment, assessment

Introduction

Persons infected with HIV are living longer, healthier lives in the era of effective combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). In fact, current life expectancy for an HIV+ individual on cART is largely comparable to that of HIV− adults (i.e., nearly 75 years old; van Sighem, Gras, Reiss, Brinkman, & de Wolf, 2010). It is estimated that by 2030, people aged 50 and older will constitute nearly three-quarters of the HIV+ population in the United States (Smit et al., 2015). Older HIV+ adults experience high rates of disability secondary to a host of disease-related (e.g. viremia), psychosocial (e.g., stigma), neurocognitive, psychiatric (e.g., depression), and comorbid (e.g., hepatitis C virus [HCV] coinfection) factors that are disproportionately represented in this at-risk group (Cardoso et al., 2013; High et al., 2012). Thus, HIV is now considered a chronic illness that has considerable relevance to rehabilitation psychology.

Despite the greying of the HIV epidemic, many older adults with HIV are still of working age and can maintain gainful employment. In fact, in international samples, it is estimated that nearly 70% of individuals with HIV are employed (Dray-Spira et al., 2012), although unemployment rates have steadily increased over the past decade (Annequin et al., 2015). In the United States, however, employment rates are lower, with some suggesting 40%–50% (Morgan et al., 2012; Rabkin, McElhiney, Ferrando, Van Gorp, & Lin, 2004). The benefits of maintaining active employment for HIV+ persons are manifold; for example, successful work engagement can enhance long-term health, quality of life, and self-esteem (Kampfe, Wadsworth, Mamoleo, & Schonbrun, 2008). Across the lifespan, employment among individuals with HIV is associated with better disease-specific health factors (e.g., shorter disease duration and higher CD4 cell counts; Auld, 2002) and higher global neurocognitive functioning (Heaton et al., 2004). Likewise, unemployment is associated with poorer psychological health, elevated concerns for stigma, and fear of HIV-related discrimination (Rodger et al., 2010). Therefore, it is important to identify risk and protective factors for optimal employment among older HIV+ adults. Yet we know little about the predictors of employment status and functioning of older HIV+ adults specifically.

As people living with HIV are getting older, the effects of aging and HIV may translate into compounded vulnerability to unemployment. In fact, rates of employment are low in older HIV+ adults, at around 35–50% (e.g., Moore et al., 2013). To date, only three studies have directly examined the combined effects of aging and HIV on employment status. One study by Burns and colleagues (2006) identified age as a significant and unique predictor of employment and disability among other demographic, disease, and functionality variables in a sample of HIV+ adults. In an unpublished dissertation, Henninger (2006) used path analyses to demonstrate that both HIV status and age were independently related to employment status. Moreover, age affected employment indirectly through its negative impact on neurocognitive functioning. Finally, a study by Morgan and colleagues (2012) examined the effects of both HIV and aging on various measures of everyday functioning, including employment. The authors found a synergistic age and HIV effect on most aspects of everyday functioning (e.g., activities of daily living), but only an HIV effect on employment status. Further, the only significant predictor of unemployment in the older HIV+ sample was current major depressive disorder, although greater medical comorbidity burden and lower neurocognitive reserve neared significance (i.e., ps<.10). This sample, however, included only 61 older HIV+ individuals who were either employed full time or were unemployed, which may have obscured effects that influence gradations in employment status (e.g., retirement).

Thus, while previous research has shown that age and HIV independently affect employment outcomes, no studies to date have examined their combined effects in a large well-characterized sample of older and younger HIV+ and HIV− adults. The present study aimed to investigate this issue using a multi-level categorization of employment status and across measures of current work functioning. We hypothesized that older adults with HIV would be at the greatest risk for disability and unemployment. Second, we sought to examine clinicodemographic predictors of employment status in older HIV+ adults. Finally, we examined the combined effects of aging and HIV on workplace performance in a subsample of participants who were employed at the time of assessment.

Method

Participants

This study included 551 participants recruited from the San Diego community and local HIV clinics, whom were assessed between the years 2005 and 2013. HIV serostatus was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and confirmed by Western blot test or by MedMira rapid HIV-1 antibody test. In total, there were 358 HIV+ and 193 HIV− comparison participants who were broadly comparable on age, education, estimated verbal IQ, and rates of substance dependence and HCV infection (ps>.05). For the present study, participants were then stratified by age (i.e., Younger: under age 50 and Older: aged 50 and above; Table 1). This age-split was selected in an effort to remain consistent with prior aging and HIV literature (e.g., Valcour et al., 2004). Further, it simultaneously allows us to readily identify the subgroup of older HIV+ individuals in whom to examine specific predictors of employment status and functioning. Of note, parallel analyses were conducted using age as a continuous variable, which confirmed that group dichotomization did not alter the significance or magnitude of the observed associations.

Table 1.

Cohort’s Demographic, Psychiatric, and Medical Characteristics

| Younger HIV − (n = 99) |

Older HIV − (n = 94) |

Younger HIV + (n = 195) |

Older HIV + (n = 163) |

p | Group Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31.4 (7.7) | 56.9 (6.1) | 37.2 (7.2) | 56.2 (5.8) | < .001 | Y− < Y+< O−, O+ |

| Education (years) | 14.4 (2.4) | 14.3 (2.8) | 13.1 (2.5) | 14.0 (2.7) | < .001 | Y+ < Y−, O−, O+ |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 48.5 | 66.0 | 55.3 | 67.5 | < .001 | Y−, Y+ < O−, O+ |

| Gender (% men) | 62.6 | 71.2 | 89.2 | 82.8 | < .001 | Y−, O− < Y+, O+ |

| Estimated verbal IQ (WTAR) | 103.9 (10.8) | 103.9 (10.8) | 102.3 (11.4) | 102.4 (12.0) | -- | -- |

| Currently employed (%) | 73.6 | 50.0 | 43.6 | 23.9 | <.001 | O+< Y+, O−< Y− |

| Hollingshead highest occupation achieved | 4.1 (1.9) | 5.5 (2.0) | 4.1 (1.8) | 5.1 (2.0) | <.001 | Y+, Y− < O+, O− |

| High level (>5) (%) | 27.8 | 55.9 | 26.9 | 43.8 | <.001 | Y+, Y− < O+, O− |

| Any lifetime affective disorders (%) | 28.3 | 41.5 | 57.9 | 61.9 | < .001 | Y− < Y+, O+ |

| Any lifetime substance dependence (%) | 35.4 | 46.8 | 54.9 | 55.2 | .005 | Y− < Y+, O+ |

| HCV (%) | 3.1 | 16.1 | 7.9 | 31.2 | < .001 | Y− < O−, O+; Y+ < O+ |

| Age at HIV infection | - | - | 26.8 (7.1) | 39.5 (8.7) | <. 001 | Y+ < O+ |

| HIV duration (months) | - | - | 125.64 (90.6) | 198.3 (90.4) | < .001 | Y+ < O+ |

| AIDS (%) | - | - | 48.5 | 66.3 | < .001 | Y+ < O+ |

| Current CD4 count (cells/µL) | - | - | 573.3 (287.6) | 561.5 (299.0) | -- | -- |

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/µL) | - | - | 240.9 (195.0) | 176.8 (169.1) | .001 | O+ < Y+ |

| Prescribed cART status (%) | - | - | 84.6 | 88.3 | -- | -- |

| RNA in plasma detectable (%) | - | - | 30.3 | 18.1 | .008 | O+ < Y+ |

| Among persons on cART | - | 18.1 | 12.3 | -- | -- | |

| Global neurocognitive z-score | 0.40 (0.5) | −0.03 (0.7) | 0.06 (0.6) | −0.29 (0.7) | < .001 | O+ < O−, Y+ < Y− |

Note. Data represent Mean (Standard Deviation) or %. Younger <50 years; Older ≥ 50 years; WTAR = Wechsler Test of Adult Reading; HCV = Hepatitis C Virus; AIDS = Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; CD4 = Cluster of Differentiation 4; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy

Participants were primarily enrolled in a neurocognitive study and thus were excluded if they had histories of severe psychiatric disorders, chronic medical, or neurological conditions such as active central nervous opportunistic infections, seizure disorders, head injury with a loss of consciousness more than 30 minutes, stroke with neurological sequealae, non-HIV-related dementias, or an estimated verbal IQ score less than 70 on the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (WTAR; Weschler, 2001). Individuals were also excluded if they met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria for substance use disorders within 1 month of evaluation or if they tested positive in a urine toxicology screen for illicit drugs (except marijuana) on the day of testing. Thus, these criteria may be somewhat conservative in estimating the frequency of unemployment in HIV and somewhat liberal in estimating the correlates unique value in classifying employment status, as many of the excluded factors (e.g., active psychiatric disorders) are strong predictors in their own right. Demographic, psychiatric, medical, and applicable HIV disease characteristics of the entire sample are presented in Table 1. The data presented below are part of a larger research program exploring everyday functioning in individuals with HIV (see Woods et al., 2011 and Morgan et al., 2012).

Materials and Procedure

The study procedures were approved by the human subjects institutional review board at the University of California, San Diego. Each participant provided written informed consent and was administered a comprehensive medical, psychiatric, and neurocognitive evaluation. The entire neurocognitive evaluation was typically performed in a single session.

Employment Variables of Interest

Information on current and prior employment was gathered in a semi-structured neurobehavioral interview administered by a certified research assistant. Each participant was classified as one of four employment statuses: Employed, Unemployed, Disabled, or Retired. Each participant was also assigned a score representing their highest occupation level based on the Hollingshead Occupational Scale (Hollingshead, 1975), which rates occupations along a continuum ranging from 1 (e.g., nonspecialized manual labor, menial service workers) to 9 (e.g., managers, higher executives, and other major professionals). For those who were employed at time of testing, information regarding their current placement was collected and coded accordingly.

Work performance was assessed using Heaton Employment Questionnaire (Heaton et al., 1994), a 28-item self-report measure of work functioning. Specifically, HIV− participants were asked to compare current performance to that of the previous year, and HIV+ participants were asked to compare current performance to the period before infection with HIV. Each item used Likert-type anchors, ranging from 1–7, such that lower scores (<4) indicated worsened or poor functioning and higher scores (>4) indicated improved or good functioning, while a score of 4 indicated “no change.” Several scales were derived from sections of the questionnaire, including a Performance scale, Demands scale, Productivity scale, and Scrutiny scale. Questions within the 4-item Performance scale pertained to the accuracy and efficiency of work product (e.g., “How would you describe your work efficiency in the last month, compared to one year ago?”). The 5-item Demands scale assessed the level of expectations of the employee (e.g., “Describe the quality of work expected of you in the last month, compared to before you were HIV positive”). Questions within the 8-item Productivity scale assessed amount and rate of work, need for assistance, and mental exertion (e.g., “Describe the rate at which you have been achieving your daily work objectives in the last month, compared to one year ago”). Finally, the 5-item Scrutiny scale assessed the amount of oversight the individual had received and the likelihood that a supervisor would notice a change in the individual’s performance (e.g., “If you had been accomplishing less work in the last month, what is the chance your supervisor would have noticed?”). In addition, a Summary scale was created by averaging the items from the Productivity and Performance scales (range 1–7; Cronbach’s alpha = .90)

Neurocognitive Evaluation

The neurocognitive evaluation included an estimate of premorbid verbal IQ (i.e., WTAR) alongside a comprehensive neurocognitive test battery designed to assess domains most commonly impacted in HIV. In accordance with the Frascati research criteria (Antinori et al., 2007), the test battery, described in full detail elsewhere (e.g., Sheppard et al., 2015), included measures of executive functions, attention/working memory, episodic learning, memory, information processing speed, and motor skills. Scores on each individual test were converted to a sample-based z-score, which were then used to create domain z-scores. Finally, a global neurocognitive deficit z-score was generated by averaging the z-scores of each of the six domains assessed.

Psychiatric Interview

Current (i.e., within the last 30 days) and lifetime major depressive disorders and substance use disorders were determined using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (version 2.1).

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using a JMP Pro software package (version 12.1.0). Nominal logistic and multiple linear regression models were used to investigate concurrent predictors of employment status and work performance, respectively. To determine the combined effects of HIV and age and employment status, dichotomous age and HIV status variables and an age × HIV status interaction term were included among other relevant predictors. For all models, including the model predicting employment status among Older HIV+ adults and the model predicting work performance in the currently employed subgroup, predictors and covariates (e.g., ethnicity, education, sex, lifetime prevalence of substance dependence) were only included if they significantly differed across groups of interest and were significantly related to the criterion variable. The critical alpha was set to p<.05.

Group differences in normally distributed variables were assessed using one-way univariate analyses of variance (ANOVA). Wilcoxon/Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess omnibus differences on non-normal variables. Pearson’s chi-squared tests were used to evaluate differences in categorical variables. Steel-Dwass tests for multiple comparisons were used for post-hoc analyses for the whole group while the less conservative Wilcoxon tests were used on the subset of the group that was employed at time of testing.

Results

Demographic and health characteristics for the stratified sample are presented in Table 1. The four groups differed on education, ethnicity, gender, highest Hollingshead Occupation achieved, global neurocognitive z-score, and the frequency of HCV coinfection, lifetime affective disorders and substance dependence (ps<.05). These variables were considered for inclusion as covariates in regression analyses.

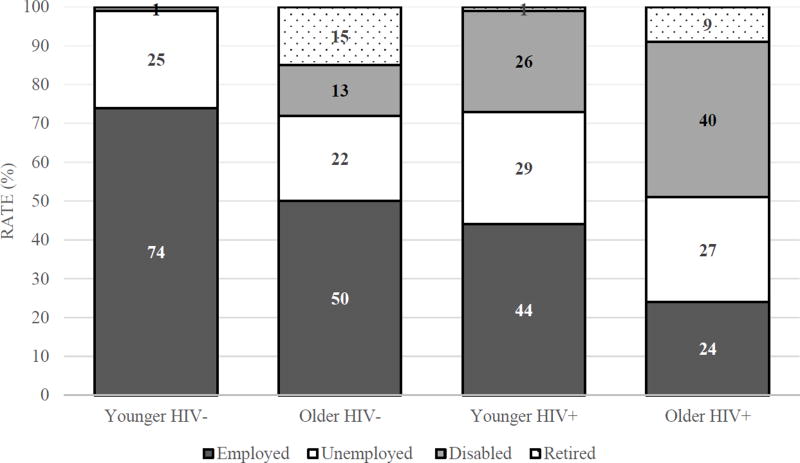

Figure 1 illustrates the rates of employment, disability, unemployment, and retirement across groups. The highest frequency of gainful employment rates were observed in the Younger HIV− group (74%) and the lowest rates were in the Older HIV+ group (24%), with the two single risk factor groups (i.e., either older or HIV+) falling intermediate (Older HIV−: 50%, Younger HIV+ 44%; Figure 1). Compared to Younger HIV+ adults, Older HIV+ adults had higher rates of disability (Older HIV+ 40%, Younger HIV+ 26%; p<.01; odds ratio [OR]: 1.9, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.2 to 2.9), higher rates of retirement (Older HIV+: 9%, Younger HIV+: 1%; p<.001; OR: 9.8, [CI]: 2.2 to 43.9), and lower rates of gainful employment (Older HIV+: 24%, Younger HIV+ 44; p<.0001; OR: 2.5, CI: 1.6 to 3.9). Compared to the Older HIV− adults, the Older HIV+ adults had higher rates of disability (HIV+: 40%, HIV−: 13%; p<.001; OR: 4.5, CI: 2.3 to 9.0) and lower rates of gainful employment (Older HIV+: 24%, Older HIV−: 50%; p<.001; OR: 3.2, CI: 1.9 to 5.5). No differences were observed for rates of unemployment or retirement (ps>.05).

Figure 1.

Frequency of employment across age and HIV serostatus

Note: None (0%) of the Younger HIV− adults were retired.

Combined Effects of Age and HIV on Employment Status

Determining covariates

All eight of the variables that different between the four groups were also associated with employment status in the full sample (all ps < .05). Thus, the final logistic regression model included all eight of these variables as covariates, along with age group, HIV group, and the age × HIV interaction term predicting the 4-level employment status outcome.

Logistic regression

Results of the logistic regression analyses examining the independent and synergistic effects of age and HIV infection on employment status produced a significant model (Χ2 [33, N=532] = 229.1, p<.0001). Main effects were observed for age (X2 = 33.0, p<.001) and HIV status (X2 = 37.7, p<.001), but the interaction term was not statistically significant (X2 = 4.9, p=.18). Other significant predictors in the model included education, Caucasian ethnicity, lifetime affective disorder, HCV coinfection, and global neurocognitive functioning (all ps < .05). Specifically, compared to the unemployed group, (1) employment was associated with protective factors that included higher education, no HCV coinfection, and no history of affective disorders (all ps < .05), (2) being disabled from employment was associated with poorer neurocognitive functioning (p < .05), and (3) retirement was associated with Caucasian ethnicity, no HCV coinfection, and poorer neurocognitive functioning (all ps < .05).

Predictors of Employment Status in Older HIV+ Adults

Exploratory analyses

Demographic, psychiatric, and medical characteristics across the 4 employment groups in the Older HIV+ sample are presented in Table 2. We conducted a series of univariate chi-squared analyses or ANOVAs with follow-up independent samples t-tests (or their non-parametric counterparts) in order to determine the clinicodemographic factors associated with employment outcomes in the Older HIV+ group. Notably, the retired group was older at assessment, acquired HIV at an older age, and had a higher proportion of Caucasians (ps<.05). The disabled group had fewer years of education, worse neurocognitive functioning, and was more frequently on cART (ps<.05). The unemployed group had the highest rate of HCV coinfection (ps>.05). The 4 employment groups did not differ on any other factor (ps > .10).

Table 2.

Demographic, Psychiatric, and Medical Characteristics of Older HIV+ Individuals Across Employment Groups

| Employed (n=39) |

Disabled (n=65) |

Retired (n=15) |

Unemployed (n=44) |

p | Group Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.4 (4.5) | 55.5 (4.3) | 68.3 (5.0) | 54.6 (4.1) | <.001 | E, U, D < R |

| Education (years) | 14.9 (2.3) | 13.5 (2.8) | 14.2 (2.7) | 13.9 (2.7) | .037 | D < E |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 71.8 | 56.9 | 100 | 68.2 | .012 | E, U, D < R |

| Gender (% men) | 74.4 | 87.7 | 93 | 79.5 | -- | -- |

| Estimated verbal IQ (WTAR) | 105.1 (9.9) | 100.4 (12.9) | 105.9 (11.0) | 101.7 (12.3) | -- | -- |

| Hollingshead highest occupation achieved | 5.1 (2.0) | 5.1 (2.2) | 5.1 (2.4) | 5.1 (1.9) | -- | -- |

| High level (>5) (%) | 46.2 | 51.5 | 50.0 | 43.18 | -- | -- |

| Any lifetime affective disorder (%) | 51.3 | 66.2 | 46.7 | 72.7 | -- | -- |

| Any lifetime substance dependence (%) | 53.8 | 61.5 | 33.3 | 54.5 | -- | -- |

| HCV (%) | 19.4 | 29.7 | 13.3 | 50.0 | .009 | R, E, D < U |

| Age at HIV infection | 38.6 (8.3) | 38.5 (8.2) | 48.6 (6.6) | 39.2 (8.9) | .002 | E, U, D < R |

| HIV duration (months) | 190.4 (94.5) | 204.1 (87.1) | 237.03 (68.5) | 184.7 (96.2) | -- | -- |

| AIDS (%) | 56.4 | 78.4 | 60.0 | 59.1 | -- | -- |

| Current CD4 count (cells/µL) | 620.2 (390.1) | 528.4 (271.8) | 584.3 (234.6) | 551.8 (267.9) | - | -- |

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/µL) | 202.9 (171.8) | 151.2 (186.8) | 223.8 (200.5) | 175.6 (119.1) | -- | -- |

| Prescribed cART status (%) | 76.9 | 95.3 | 86.6 | 88.6 | .043 | E < D |

| RNA in plasma detectable (%) | 21.1 | 12.5 | 26.7 | 20.9 | -- | -- |

| Among persons on cART | 10.0 | 11.3 | 15.4 | 15.8 | -- | -- |

| Global neurocognitive z-score | −0.11 (0.5) | −0.47 (0.7) | −0.55 (0.8) | −0.11 (0.6) | .008 | D < E, U |

Note. Data represent M (SD) or %. Younger <50 years; Older ≥ 50 years; WTAR = Wechsler Test of Adult Reading; HCV = Hepatitis C Virus; AIDS = Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; CD4 = Cluster of Differentiation 4; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy

Logistic regression

Next, a multivariable logistic regression model was conducted in order to determine the independent predictors of employment outcomes in the Older HIV+ group. This model included all of the factors listed above that were significantly associated with employment group in the Older HIV+ sample (i.e., age, education, ethnicity, HCV coinfection, global neurocognitive z-score, cART status, and age at HIV infection), which were regressed on the 4-level employment outcome in the Older HIV+ group. Results yielded an overall significant model (Χ2 [18, N=157] = 133.2, p<.0001). The significant, independent predictors of employment status in Older HIV+ group were age, HCV coinfection, age at HIV infection, cART status, and global neurocognitive functioning (all ps < .05). Specifically, compared to the unemployed group, (1) employment in the Older HIV+ group was associated with no HCV coinfection and not being on cART (all ps < .05), (2) being disabled from employment was associated with poorer neurocognitive functioning, being younger at contraction of HIV, and not having HCV coinfection (all ps < .05).

Effects of Age and HIV on Work Performance Among the Employed Participants

Sample identification and determination of covariates

The demographic, psychiatric, and medical characteristics of a subsample of 107 participants who were employed at the time of assessment are presented in Table 3. Due to differences in study protocols, 139 participants who were classified as employed did not have work performance data and thus are not included here. The 107 participants with current work performance data did not differ from the 139 participants without such data in any clinicodemographic variable listed in Table 1 (all ps > .10). Among the 107 participants, we observed group differences in education and gender (ps < .05). In particular, pairwise comparisons showed that the Younger HIV+ group had a higher proportion of men than both HIV− groups and had obtained less education than the two Older groups (ps < .05).

Table 3.

Demographic, Psychiatric, and Medical Characteristics of the 107 Participants with Current Work Functioning Data

| Younger HIV − (n = 34) |

Older HIV − (n = 25) |

Younger HIV + (n = 31) |

Older HIV + (n = 17) |

p | Group Differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 29.0 (5.9) | 56.6 (6.2) | 31.9 (5.1) | 54.6 (4.8) | < .001 | Y− < Y+ < O−, O+ |

| Education (years) | 14.3 (2.3) | 15.3 (2.9) | 13.6 (2.1) | 15.8 (1.9) | .004 | Y+ < O−, O+ |

| Ethnicity (% white) | 50.0 | 68.0 | 48.4 | 82.4 | -- | -- |

| Gender (% men) | 67.7 | 72.0 | 93.6 | 76.5 | .045 | Y−, O− < Y+ |

| Estimated verbal IQ (WTAR) | 104.5 (9.0) | 108.6 (8.5) | 102.9 (9.5) | 105.5 (8.5) | -- | -- |

| Any lifetime affective disorder (%) | 38.2 | 44.0 | 67.8 | 47.1 | -- | -- |

| Any lifetime substance dependence (%) | 29.4 | 32.0 | 51.6 | 35.3 | -- | -- |

| HCV (%) | 5.9 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 11.8 | -- | -- |

| Age at HIV infection | - | - | 27.2 (6.9) | 39.1 (9.5) | <. 001 | Y+ < O+ |

| HIV duration (months) | - | - | 56.7 (48.1) | 186.6 (108.6) | < .001 | Y+ < O+ |

| AIDS (%) | - | - | 29.0 | 58.8 | .044 | Y+ < O+ |

| Current CD4 count (cells/µL) | - | - | 634.6 (240.7) | 579.9 (370.4) | -- | -- |

| Nadir CD4 count (cells/µL) | - | - | 335.7 (192.8) | 185.1 (162.5) | .009 | O+ < Y+ |

| Prescribed cART Status (%) | - | - | 80.7 | 70.6 | -- | -- |

| RNA in plasma detectable (%) | - | - | 30.8 | 29.4 | -- | -- |

| Among persons on cART | - | 14.3 | 16.7 | -- | -- | |

| Global neurocognitive z-score | 0.21 (0.5) | 0.06 (0.7) | −0.01 (0.6) | −0.47 (0.7) | .008 | O+ < Y+, O−, Y− |

Note. Data represent M (SD) or %. Younger <50 years; Older ≥ 50 years; WTAR = Wechsler Test of Adult Reading; HCV = Hepatitis C Virus; AIDS = Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome; CD4 = Cluster of Differentiation 4; cART = combination antiretroviral therapy

For the work performance characteristics listed in Table 4, gender was only related to work Scrutiny and thus was only a covariate in that analysis. Education, on the other hand, was related to all of the variables listed in Table 4 with the sole exception of Hollingshead change score and thus was a covariate for all analyses.

Table 4.

Work Performance Characteristics of the 107 Participants With Current Work Functioning Data

| Pairwise comparisons (versus O+) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Younger HIV − (n = 34) |

Older HIV − (n = 25) |

Younger HIV + (n = 31) |

Older HIV + (n = 17) |

Y− | Y+ | O− | Adj. R2 |

|

| Hollingshead | ||||||||

| Highest occupation achieved | 5.5 (1.9) | 7.0 (1.1) | 5.3 (1.7) | 6.7 (1.6) | * | ns | ns | .46a** |

| High level (>5) (%) | 51.5 | 80.0 | 45.2 | 82.4 | ||||

| Current occupation | 4.4 (1.9) | 6.4 (2.1) | 4.6 (2.1) | 6.1 (2.1) | * | ns | ns | .37a** |

| High level (>5) (%) | 23.5 | 64.0 | 38.7 | 75.0 | ||||

| Change from highest | 1.1 (1.7) | 0.6 (1.2) | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.5) | ns | ns | ns | −.01a |

| Heaton Work Questionnaire | ||||||||

| Summary | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.1 (0.8) | 4.0 (0.5) | 3.9 (1.1) | * | ns | ns | .10a** |

| Performance | 4.5 (1.1) | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.1 (0.7) | 3.9 (1.1) | * | ns | ns | .08a* |

| Productivity | 4.5 (0.9) | 4.0 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.5) | 3.9 (1.0) | * | ns | ns | .10a** |

| Demands | 4.3 (1.2) | 4.5 (0.7) | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.7 (1.2) | ns | ns | ns | −.01 |

| Scrutiny | 3.8 (1.1) | 4.4 (1.6) | 3.7 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.8) | * | ns | ns | .14b** |

Note. Hollingshead occupation scores range from 1 (e.g., farm laborers, menial service workers) to 9 (e.g, higher executives, major professionals such as physicians, engineers, government officials). The median higher occupation score of the whole sample was 5 (e.g., clerical and sales workers, small farm and business owners). Scores on the Heaton Work Questionnaire had a possible range of 1–7, such that lower scores (<4) indicated worsened or poor functioning and higher scores (>4) indicated improved or good functioning, and a score of 4 indicated no change.

Mean (Standard Deviation). ns = not significant, p>.05.

adjusting for education.

adjusting for education and sex.

p<.05

p<.01

Multiple regressions

We conducted a multiple regression using the 4-level age-HIV group as the primary predictor of the 8 continuous work performance listed in Table 4, with covariates as defined above. A consistent pattern emerged whereby education and the 4-level age-HIV group variable were significant, independent predictors of the highest (adjusted R2 = .46) and current (adjusted R2 = .37) Hollingshead scores, as well as Work Summary (adjusted R2 = .10), Performance (adjusted R2 = .08), Productivity (adjusted R2 = .10), and Scrutiny (adjusted R2 = .14; all ps < .05) scores. In each of these models, pairwise comparisons showed that the Older HIV+ group reported poorer functioning only as compared to the Younger HIV− sample (ps < .05; Table 4). The overall models for Hollingshead change and work Demands were not significant (ps > .10).

Predictors of Work Performance in Older HIV+ Adults

Finally we were interested in examining the clinicodemographic correlates (i.e., all variables in Table 3) of current work scores in the small sample of Older HIV+ participants. Results revealed that better work performance was associated with higher CD4 count (r=0.51, p=.04) and fewer years of education (r=−0.6, p=.01). In contrast, none of the other health or demographic variables listed in Table 3 were related to work performance in either the Older HIV− or Younger HIV+ group (ps > .10).

Discussion

With the growing number of older adults living with HIV, it is important to understand the unique and combined risks of older age and HIV disease on employment outcomes. The primary objectives of the present study were therefore to investigate the effects of aging and HIV serostatus on employment status and functioning, to identify predictors of employment in older HIV+ adults, and to examine workplace performance among employed older HIV+ persons. Findings revealed that older age and HIV infection impose additive and independent effects on employment status. These findings were independent of important clinicodemographic factors (e.g., education, ethnicity). In our sample, the Older HIV+ adults evidenced the highest rates of disability. Within the Older HIV+ group, being employed was associated with the absence of HCV co-infection and lower rates of cART. Nevertheless, among persons who were able to maintain gainful employment, the self-reported work performance of Older HIV+ individuals was comparable to that of their Younger HIV+ and Older HIV− counterparts, though worse than that of Younger HIV− adults. The implications and limitations of these various findings are discussed in detail below.

The present study revealed additive and independent adverse effects of older age and HIV infection on employment status, rather than a compounding (i.e., synergistic) effect of these two risk factors. Specifically, there was a stair-step effect of older age and HIV status (Figure 1) across the groups on employment status, which seems to be characterized by high rates of disability (40%) in the Older HIV+ group. Among older adults who were not gainfully employed, HIV+ persons were more than twice as likely to be disabled (53%) as compared to those who were HIV− (25%). Additionally, among the HIV+ adults who were unemployed, rates of retirement were higher in the Older (12%) adults relative to the Younger (2%) adults. Importantly, these additive effects are not better explained by the other demographic factors (e.g., education), psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression), or medical comorbidities (e.g., HCV). Thus, it appears that older age and HIV status are parallel risk factors that do not interact to create an enhanced vulnerability to adverse changes in employment status that is greater than either risk factor would confer independently. This finding is in contrast to past research demonstrating synergistic effects (i.e., interactions) of HIV and older age on other aspects of everyday functioning (Morgan et al., 2012). For instance, older adults with HIV demonstrate significantly reduced capability to take care of basic tasks (e.g., housekeeping, bathing) or carry on instrumental aspects of daily living (e.g., cooking, financial management) relative to what would be expected given the deficits seen in older age or HIV disease status independently. With regard to employment, there may be other moderating variables that may serve to protect older HIV+ adults from the synergism seen in these other aspects of daily functioning.

To that end, the present findings revealed several clinicodemographic variables that may influence the employment status of older HIV+ adults. Our results suggested an unexpected role of disease variables in their association with employment status. Notably, Older HIV+ adults who were employed were less likely to be on cART than those who were disabled, despite nonsignificant differences between groups on measures of immunovirological functioning (e.g., CD4 count; Table 2). Post-hoc analyses indicate that this same pattern of findings was also present in the Young HIV+ sample (data not shown). This finding was surprising in light of the evidence suggesting that cART can improve work outcomes in certain settings (Elzi, et al., 2016; Linnemayr, Glick, Kityo, Mugyeni, & Wagner, 2013). A possible explanation for this may be due to the side effects of cART; fatigue, diarrhea, and insomnia are among the most commonly experienced symptoms and can affect work productivity (DiBonaventura, Gupta, Cho, & Mrus, 2012). Additionally, the lower prevalence of cART among employed individuals suggests that actual immune functioning and disease management do not increase an individual’s risk of being unemployed due to disability. It is possible that other moderating factors (e.g., psychosocial variables) or the lack of overt manifestations of health declines that might impact an individual’s capacity to work would influence employment status above and beyond traditional disease characteristics. Indeed, financial (e.g., disability benefits), psychiatric (e.g., major depression), and medical (e.g., physical limitations) factors have been shown to influence employment status in HIV+ individuals to a greater degree than do health indicators such as CD4 count (Rabkin et al., 2004; cf. Burns et al., 2006). Future research may seek to compare the contributions of these variables in influencing changes in employment between younger and older HIV+ adults.

Our findings suggested that some clinicodemographic characteristics served as protective factors in older HIV+ adults. For instance, we found that retired Older HIV+ adults were older at infection, more likely to be Caucasian, and less likely to have a history of affective disorders than unemployed or disabled Older HIV+ adults. In contrast, post-hoc analyses on the Older HIV− sample showed no such differences in either race or psychiatric history (ps > .10), suggesting that these characteristics may serve as protective factors in older HIV+ adults. Indeed, affective disorders, particularly the presence of depression, have consistently been associated with poorer work outcomes in various clinical populations, including individuals with HIV (Rabkin et al., 2004). Further, infection at an older age may allow economic (e.g., financial stability, sufficient health care), and psychosocial buffers to be established before the HIV-related changes (e.g., cardiovascular complications) may occur and negatively impact an individual’s life. Lastly, HIV still disproportionately affects ethnic and racial minorities (CDC, 2014). African Americans and Latinos for example, are particularly susceptible to higher rates of serious medical conditions including diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Jones & Hall, 2006) that may prevent these individuals from working long enough to retire comfortably. Future research should examine what other social, economic, and health variables serve to protect older HIV+ adults from unemployment and/or disability.

Despite the additive risk of older age and HIV on employment outcomes, work performance of older HIV+ individuals appear to be comparable to persons with only one risk factor (e.g., older age or younger persons with HIV). Although older HIV+ adults are not performing at optimal levels, as evidenced by poorer work functioning relative to younger HIV− participants (Table 4), there is no evidence of either a synergistic or additive effect of HIV and older age. In other words, work performance is not dually compromised by older age and HIV status. This finding is consistent with additional unpublished results from Henninger (2006) that demonstrated that older HIV+ adults did not differ from younger HIV+ adults on skills-based measures of vocational functioning. Collectively, these results suggest a discrepancy between factors that influence an individual’s ability to maintain gainful employment and capacity to perform duties at work. It is possible that older age and HIV disease may additively impact domains that influence an individual’s decision to retain in or refrain from employment such as financial incentives (e.g., job benefits), social barriers (e.g., stigma or discrimination), health issues (e.g., comorbid medical or psychological conditions), or quality of life (Barkey, Watanabe, Solomon & Wilkins, 2009; Elzi, et al., 2016; Morgan et al., 2012).

There are several limitations to the current study that are worth noting. The subset of participants who were employed at time of testing was relatively small (N=107), especially when categorized by age group and HIV status. Specifically, null results on work performance variables within the currently employed adults should be interpreted with caution. However, despite the risk of being underpowered with small sample sizes (N=17), medium effect sizes were evidenced on some metrics (e.g., Productivity, Younger HIV− and Older HIV+, Cohen’s d = .60), suggesting the presence of a robust effect whose reliability remains to be determined. Moreover, it is important to note that the measure of work performance was a self-report questionnaire, which like all subjective indicators is subject to influence by social desirability and recall biases (e.g., Thames et al., 2010). Further, it is worth noting the potential age bias within the HIV+ participants in the interpretation of the self-report of measure of work functioning. Older adults likely had different job responsibilities or entire occupations before HIV contraction, which for some individuals was 30 years prior. Therefore, future work may seek to factor in more objective indicators of job performance (e.g., employer reviews) and other aspects of job role and responsibilities (e.g., specific activities and necessary skills) into analysis to overcome these limitations. Lastly, our secondary interest in the role of neurocognition to employment status and workplace functioning informed our exclusionary criteria, which may have limited the representativeness of our sample to that of the greater working population.

Despite these limitations, the present findings add to the growing body of literature testifying that older HIV+ adults present as a vulnerable, but also resilient clinical population that warrants greater research attention. In fact, recent reports in the United States suggest that nearly 65% of older HIV+ report self-rated successful aging, and interestingly, although they report more psychosocial stress and worse physical and mental functioning that HIV− adults, measures of resilience such as optimism, personal mastery, and social support were comparable (Moore et al., 2014). Through the current study, researchers and clinicians can better understand the role of important demographic variables (e.g., age) and biological (e.g., immunovirological factors) variables to the employment outcomes of older adults with HIV. From rehabilitation psychological perspective, there are many reasons why HIV+ individuals may benefit from maintaining employment. Factors associated with gainful employment (e.g., learning new skills, enriching personal and social environment) may promote neurocognitive reserve and protect against worsening physical and neurocognitive functioning (Vance et al., 2015). Future research should aim to expand on the present findings and identify variables that predict transitions in employment in HIV in an effort to inform clinical decision-making.

Impact and Implications.

With the aging of the HIV population in the United States, this study addresses important questions that have emerged regarding the clinicodemographic factors that are associated with optimal vocational functioning across the lifespan in HIV disease.

Findings from this study extend the current literature by demonstrating that older age and HIV seropositivity have additive, adverse effects on employment status – but not necessarily current work functioning – independent of relevant demographic, psychiatric, and medical co-factors.

Vocational rehabilitation professionals may wish to focus efforts on those unemployed or disabled older HIV+ adults who may be candidates for re-entry into the workforce by virtue of leveraging potential protective factors (e.g., remediating affective disorders).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01-MH73419, T32-DA031098, and P30-MH62512. The authors would like to thank Katie L. Doyle and Erica Weber for their assistance with data collection, processing, and helpful comments on earlier versions of this project. The authors also extend additional thanks to Gunes Avci, Kelli Sullivan, and Savanna Tierney for their thoughtful comments during the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Aspects of this data were presented at the 124th American Psychological Association Annual Convention in Denver, Colorado.

References

- Annequin M, Lert F, Spire B, Dray-Spira R VESPA2 Study Group. Has the employment status of people living with HIV changed since the early 2000s? AIDS (London, England) 2015;29(12):1537–1547. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistics manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Auld MC. Disentangling the effects of morbidity and life expectancy on labor market outcomes. Health Economics. 2002;11(6):471–483. doi: 10.1002/hec.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkey V, Watanabe E, Solomon P, Wilkins S. Barriers and facilitators to participation in work among Canadian women living with HIV/AIDS. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2009;76(4):269–275. doi: 10.1177/000841740907600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns SM, Young LR, Maniss S. Predictors of employment and disability among people living with HIV/AIDS. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2006;51(2):127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso SW, Torres TS, Santini-Oliveira M, Marins LMS, Veloso VG, Grinsztejn B. Aging with HIV: a practical review. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;17(4):464–479. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBonaventura Md, Gupta S, Cho M, Mrus J. The association of HIV/AIDS treatment side effects with health status, work productivity, and resource use. AIDS Care. 2012;24(6):744–755. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray-Spira R, Legeai C, Le Den M, Boué F, Lascoux-Combe C, Simon A, Meyer L. Burden of HIV disease and comorbidities on the chances of maintaining employment in the era of sustained combined antiretroviral therapies use. AIDS. 2012;26(2):207–215. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834dcf61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzi L, Conen A, Patzen A, Fehr J, Cavassini M, Calmy A, Battegay M. Ability to work and employment rates in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1-infected individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy: The swiss HIV cohort study. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2016;3(1) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison KM, Song R, Zhang X. Life expectancy after HIV diagnosis based on national HIV surveillance data from 25 states, United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;53(1):124–130. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b563e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, Woods SP, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis RJ, Grant I. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton RK, Velin RA, McCutchan JA, Gulevich SJ, Atkinson JH, Wallace MR, Grant I. Neuropsychological impairment in human immunodeficiency virus-infection: Implications for employment. HNRC group. HIV neurobehavioral research center. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1994;56(1):8. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- High KP, Brennan-Ing M, Clifford DB, Cohen MH, Currier J, Deeks SG, Volberding P. HIV and aging: state of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;60:S1–S18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825a3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henninger DE. Ecological validity of neuropsychological assessment: The roles of vocational assessment and employment in aging HIV+ adults. Dissertations Abstracts International. 2006;67(05):2859. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Lam MN, Stefaniak M. Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse. AIDS (London, England) 2004;18(Suppl 1):S19. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200418001-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AA. Four-factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DW, Hall JE. Racial and ethnic differences in blood pressure: Biology and sociology. Circulation. 2006;114(25):2757–2759. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampfe CM, Wadsworth JS, Mamboleo GI, Schonbrun SL. Aging, disability, and employment. Work. 2008;31(3):337–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnemayr S, Glick P, Kityo C, Mugyeni P, Wagner G. Prospective cohort study of the impact of antiretroviral therapy on employment outcomes among HIV clients in Uganda. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2013;27(12):707–714. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Moore DJ, Thompson W, Vahia IV, Grant I, Jeste DV. A case-controlled study of successful aging in older adults with HIV. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):e417. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan EE, Iudicello JE, Weber E, Duarte NA, Riggs PK, Delano-Wood L, Woods SP. Synergistic effects of HIV infection and older age on daily functioning. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2012;61(3):341–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826bfc53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Moore DJ, Thompson WK, Vahia IV, Grant I, Jeste DV. A case-controlled study of successful aging in older HIV-infected adults. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):417–423. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin JG, McElhiney M, Ferrando SJ, Van Gorp W, Lin SH. Predictors of employment of men with HIV/AIDS: a longitudinal study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66(1):72–78. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000108083.43147.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodger AJ, Brecker N, Bhagani S, Fernandez T, Johnson M, Tookman A, Bartley A. Attitudes and barriers to employment in HIV-positive patients. Occupational Medicine (Oxford, England) 2010;60(6):423–429. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard DP, Iudicello JE, Bondi MW, Doyle KL, Morgan EE, Massman PJ, Woods SP. Elevated rates of mild cognitive impairment in HIV disease. Journal of NeuroVirology. 2015;21(5):576–584. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0366-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit M, Brinkman K, Geerlings S, Smit C, Thyagarajan K, van Sighem A, Hallett TB. Future challenges for clinical care of an ageing population infected with HIV: a modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2015;15(7):810–818. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00056-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thames AD, Becker BW, Marcotte TD, Hines LJ, Foley JM, Ramezani Ay, Hinkin CH. Depression, cognition, and self-appraisal of functional abilities in HIV: An examination of subjective appraisal versus objective performance. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2011;25(2):224–243. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2010.539577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading: WTAR. Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Valcour V, Shikuma C, Shiramizu B, Watters M, Poff P, Selnes O, Sacktor N. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals The Hawaii Aging with HIV-1 Cohort. Neurology. 2004;63(5):822–827. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134665.58343.8d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance DE, Cody SL, Yoo-Jeong M, Jones GD, Nicholson WC. The role of employment on neurocognitive reserve in adults with HIV: A review of the literature. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2015;26(4):316–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Sighem A, Gras L, Reiss P, Brinkman K, de Wolf F. Life expectancy of recently diagnosed asymptomatic HIV-infected patients approaches that of uninfected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24(10):1527–1535. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a3946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SP, Weber E, Weisz BM, Twamley EW, Grant I HIV Neurobehavioral Research Programs Group. Prospective memory deficits are associated with unemployment in persons living with HIV infection. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2011;56(1):77–84. doi: 10.1037/a0022753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]