Abstract

Background

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is a major cause of premature mortality in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Worsening insulin sensitivity (IS) independent of glycemic control may contribute to the development of DKD. We investigated the longitudinal association of IS with hyperfiltration and increased albumin excretion in adolescents with T2D.

Study Design

Observational, prospective cohort study.

Setting & Participants

532 TODAY (Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth) participants ages 12–17 years with T2D duration <2-years at baseline. The TODAY study was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial that examined the efficacy of three treatment regimens (metformin monotherapy, metformin plus rosiglitazone, or metformin plus an intensive lifestyle intervention program) to achieve durable glycemic control.

Predictors

Natural log-transformed estimated insulin sensitivity [reciprocal of fasting insulin (eIS)], HbA1c, age, race-ethnicity, treatment group, BMI, loss of glycemic control and hypertension.

Outcomes

Hyperfiltration was defined as ≥99th percentile of estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR ≥140 mL/min/1.73m2] when referenced to healthy adolescents (NHANES 1999–2002) and albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) ≥30μg/mg at 3 consecutive annual visits.

Results

Hyperfiltration was observed in 7.0% of participants at baseline and in 13.3% by 5-years, with a cumulative incidence of 5.0% over 5-years. The prevalence of increased albumin excretion was 6% at baseline and 18% by 5-years, with a cumulative incidence of 13.4%. There was an 8% increase in risk of hyperfiltration per 10% lower eIS in unadjusted and adjusted models (p=0.01). Increased albumin excretion was associated with HbA1c, but not eIS.

Limitations

Longer follow-up is needed to capture the transition from hyperfiltration to rapid GFR decline in youth onset type 2 diabetes.

Conclusions

Lower eIS was associated with risk for hyperfiltration over time, whereas increased albumin excretion was associated with hyperglycemia in youth-onset T2D.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), insulin sensitivity, increased albumin excretion, hyperfiltration, Cystatin C, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), Diabetic kidney disease (DKD), Albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR), children, adolescents, disease progression, renal function, youth-onset T2DM

Introduction

Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) remains the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (1). Early DKD, including hyperfiltration and increased albumin excretion, is common in youth with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and progresses at an alarming rate. A prevalence of 24% for hyperfiltration and 34% for increased albumin excretion has been reported in a small cohort of 46 adolescents with T2D (2). We previously examined longitudinal data from the Treatment Options for Type 2 Diabetes in Adolescents and Youth (TODAY) study, showing that the prevalence of increased albumin excretion rose from 6.3% of participants at baseline to 16.6% by the end of the study period (3). However, at the time of that publication, average time of follow-up was only 3.9 years, and laboratory data needed to assess hyperfiltration was not available.

Youth-onset T2D appears to carry a particularly high risk of progressive DKD, significantly greater than in youth-onset type 1 diabetes or in adult-onset T2D of similar disease duration (3–10). The early stages of DKD are clinically silent for many years, yet renal parenchymal damage progresses during this time(11). Hyperfiltration is an early indicator of DKD, often preceding increased albumin excretion and kidney function decline (12,13). Therefore, identification of clinical phenotypes that are associated with hyperfiltration and predictive of DKD progression is needed to improve outcomes in adolescents with T2D. Specifically, reduced insulin sensitivity (IS) is associated with the development of future kidney disease in adults with and without T2D (14,15). While the mechanisms underlying the relationship between reduced IS and DKD remain unclear, experimental evidence suggests that the energy profile of T2D cannot accommodate the renal hypermetabolism of DKD (16–18). Associations between insulin resistance and hyperfiltration have been reported in a small cross-sectional cohort of adolescents with T2D (2), but data on hyperfiltration are lacking in larger cohorts as are longitudinal hyperfiltration data in adolescents with T2D. Cross-sectional relationships between insulin resistance and increased albumin excretion were previously reported in adolescents with T2D in the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study (19) but longitudinal data on these relationships are also lacking. To our knowledge, there are no longitudinal data on the relationship between IS and hyperfiltration or increased albumin excretion in adolescents with T2D.

Our aim was to add to our previous work by describing the prevalence and incidence of hyperfiltration (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥ 99th percentile for healthy controls) in the TODAY study of youth-onset T2D at baseline and over 5 years, as well as extending the albumin excretion data previously reported out to 5 years. Moreover, we sought to investigate the longitudinal relationship between estimated IS (eIS) and renal outcomes over the 5 years of study. Considering our previous cross-sectional data, we hypothesized that lower eIS in adolescents with T2D would be associated with DKD, reflected by increased risk of hyperfiltration and increased albumin excretion.

Methods

Study population and design

The TODAY study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00081328) was a multicenter, randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate three treatment therapies in children and adolescents with TDM. Beginning in July 2004 and ending in February 2009, 699 participants were randomly assigned to metformin monotherapy, metformin plus rosiglitazone, or metformin plus an intensive lifestyle intervention program (materials developed and used for the TODAY standard diabetes education program and the intensive lifestyle intervention program are available to the public at https://today.bsc.gwu.edu). Eligibility criteria included youth 10–17 years of age with type 2 diabetes according to American Diabetes Association criteria with diabetes duration <2 years, body mass index (BMI) ≥85th percentile, negative testing for diabetes-associated autoantibodies, fasting C-peptide >0.6 ng/mL, and an adult caregiver willing to support study participation. Participants were excluded for refractory hypertension, defined as blood pressure (BP) ≥150/95 mmHg despite appropriate medical therapy, or a calculated Cockcroft-Gault creatinine clearance <70 mL/min (21). The primary objective of the parent study was to compare the three treatment arms in terms of time to treatment failure, classified as a loss of glycemic control (defined as HbA1c ≥8% for 6 months or sustained metabolic decompensation requiring insulin). Half the cohort reached the primary endpoint and results demonstrated that adding rosiglitazone to metformin was associated with more durable glycemic control after an average follow-up of 3.86 years (22). Insulin was initiated at the time of primary outcome. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions, and appropriate informed consent and assent was obtained.

This study is a secondary analysis using observational data from the parent TODAY clinical trial. Of the 699 TODAY participants, 137 were excluded who did have baseline eIS and/or eGFR data, leaving a final cohort of 532 subjects. Excluded participants did not differ significantly on any demographic or baseline characteristic (sex, race-ethnicity, age, BMI or HbA1c) from the 699 in the original cohort. Analyses included data available on TODAY participants at each annual visit time points up to 60 months of follow-up.

Data collection and laboratory analysis

The methods of the TODAY trial, including laboratory analyses, study definitions, and data collection protocols, have been previously reported in detail (20). Briefly, samples were obtained at baseline and annually and processed immediately according to standardized procedures and shipped on dry ice for analysis at the TODAY central biochemical laboratory (20). Estimated insulin sensitivity (eIS) was calculated annually as the reciprocal of fasting insulin (in units of mL/μU), which correlates strongly with hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp–derived in vivo IS in obese youth with or without type 2 diabetes (23). Concentrations of creatinine in serum and urine were determined by using the Creatinine Plus enzymatic Roche reagent on a Modular P analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Inc., Indianapolis, IN), which is traceable to the IDMS reference standard. Concentration of cystatin C in serum was measured immunochemically by using Siemens reagents (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics. Inc, Newark, DE) on a Siemens nephelometer autoanalyzer (BNII). This method is standardized against the IFCC/ERM DA-471 Reference Material (RT Corp, Laramin WY).

Measurements and definitions of study outcomes

eGFR was calculated using the Zappitelli combined creatinine and cystatin C equation (eGFR = 25.38 * (1/serum cystatin C)0.331 * (1/serum creatinine)0.602 * (1.88height)) which has demonstrated strong agreement with measured GFR in adolescents (25,26). Due to the large variability of eGFRs over time in the cohort, a conservative approach was used in the present study to define presence of hyperfiltration. First, elevated GFR was defined as an eGFR ≥ 99th percentile [≥140 mL/min/1.73m2] when referenced to a nationwide sample of healthy adolescent controls (NHANES 1999–2002 (26)). Second, a participant was classified as having hyperfiltration only if the eGFR was elevated on 3 consecutive annual visits. While this approach may underestimate the number of participants with hyperfiltration in our analyses, it ensures the stability and persistence of elevated values over time.

Urine albumin excretion (albumin-creatinine ratio [ACR]) was measured at baseline and annually thereafter. Spot urine samples were obtained after a 10–14hr overnight fast. Increased albumin excretion (referred to as albuminuria in previous TODAY publications) was defined as an ACR of ≥30 μg/mg on two of three urine samples collected over a 3-month minimal period (21). Severely increased albumin excretion (previously termed macroalbuminuria) was defined as ACR ≥ 300μg/mg.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4 for Windows; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To account for multiple observations per participant, generalized estimating equations models were used to evaluate the longitudinal changes over discrete-time for eIS, eGFR and ACR. Analyses employed the natural log-transformed ACR and eIS to better approximate a normal distribution and are presented as the geometric mean and the 95% asymmetric confidence limits. The assumption of missing completely at random was used for missing data. Average annual change was obtained from similar models with time entered as a continuous measure. We include unadjusted models and models adjusted for sex, race-ethnicity, treatment group, baseline BMI, HbA1c, age, treatment failure status (loss of glycemic control yes/no), and hypertension diagnosis. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using only data from participants while still in glycemic control to assure reported results were not biased as insulin therapy was started after failure to maintain glycemic control and could interfere with the measurement of eIS.

The cumulative incidence of events over time was estimated using a Kaplan-Meier estimate and Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the relationships between eIS and incident increased albumin excretion and hyperfiltration. Participants with existing hyperfiltration or increased albumin excretion at baseline were excluded from all time-to-event analyses. Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models were evaluated using eIS as a time-dependent variable, while adjusting for sex, race-ethnicity, and treatment group (as fixed covariates) and age, BMI, HbA1c, hypertension diagnosis, and primary outcome status (loss of glycemic control) as time-dependent covariates. In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for ACE-I/angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) use rather than hypertension diagnosis. Similar Cox models were used to examine the relationships between eGFR with incident increased albumin excretion, and between ACR with incident hyperfiltration. The proportional hazards assumption in the Cox model was assessed with graphical methods and with models including time-by-covariate interactions; all covariates tested met the assumption. All analyses were considered exploratory and P<0.05 was the cut-off used to determine statistical significance.

Results

Longitudinal changes in eGFR, ACR and eIS

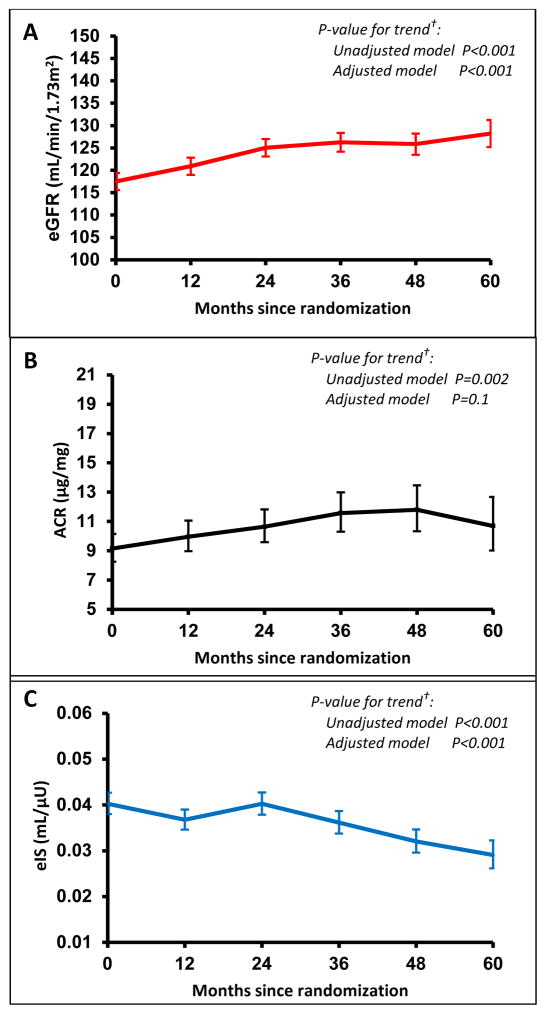

Table 1 shows participant characteristics at baseline for the 532 participants included in the analysis. Figure 1 presents eGFR, ACR and eIS annually during the 5-year study period. There was an annual increase in eGFR by a mean of 2.45±0.28 (standard error) mL/min/1.73m2 (p<0.001), an average increase in ACR of 5.5% per year (p=0.002), and an average decrease in eIS of 5.4% per year (p<0.001). These linear trends remained significant for eGFR in fully adjusted models (Figure 1, Table S1). At baseline, 1.5% of the participants had severely increased albumin excretion, with no significant increase over time. When examined only in participants who remained in glycemic control, eGFR still increased (p=0.003) and eIS still decreased over time (p=0.01), while at a lower but still significant rate, and the trends remained significant in fully adjusted models (Table S2).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the sample

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Female (%) | 340 (63.9%) |

| Age (y) | 13.9 ± 2.0 |

| Diabetes duration (m) | 7.9 ± 5.9 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 179 (33.6%) |

| Hispanic | 229 (43.0%) |

| White non-Hispanic | 107 (20.1%) |

| Other | 17 (3.2%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 35 ± 8 |

| Blood pressure (mm Hg) | |

| Systolic | 113 ± 11 |

| Diastolic | 66 ± 8 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB use | 25 (4.7%) |

| Hypertension diagnosis | 100 (18.8%) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.61 ± 0.13 |

| Serum cystatin C (mg/L) | 0.75 ± 0.12 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.0 ± 0.7 |

N = 532. Values are shown as mean mean ± SD or count (percentage).

Figure 1. Annual longitudinal changes for (A) mean eGFR, (B) median ACR and (C) median eIS (along with 95% CI error bars) across the 5 years in the TODAY study*.

*The arithmetic mean and 95% CI error bars is shown for eGFR (A) values over time. The geometric mean and 95% CI error bars is shown for ACR (B) and eIS (C) due to skewed distributions. The geometric mean is a good approximation of the median as the log-transformed data is approximately symmetric. Data shown in figures from all participants, irrespective of whether participants lost glycemic control.

†P-value from an unadjusted model testing for linear trend over time, and from adjusted model including sex, race-ethnicity, treatment group, baseline BMI, baseline HbA1c, age at baseline, treatment failure status (loss of glycemic control yes/no), and hypertension diagnosis.

Hyperfiltration and increased albumin excretion

At baseline, 12.8% of the participants had an elevated eGFR [≥140 mL/min/1.73m2] and 26.8% had elevated eGFR at year 5 (Table S1). Presence of hyperfiltration (based on first of 3 consecutive annual elevated eGFR values) was observed in 7.0% of participants at baseline and 13.3% at 5 years (Table S1), with a cumulative incidence of 5.0% over 5 years (Figure 2). The prevalence of increased albumin excretion was 6.0% at baseline and 18.0% at 5 years (Table S1), with a cumulative incidence of 13.4% over 5 years. The cumulative incidence of increased albumin excretion has been previously reported (3).

Figure 2. Cumulative incidence curves for time to hyperfiltration by Zappitelli combined creatinine and cystatin C equation during TODAY*.

*Participants with hyperfiltration at baseline are excluded. Time to hyperfiltration defined at the first of three consecutive annual visits with eGFR ≥ 99th percentile for NHANES controls (i.e, eGFR ≥ 140ml/min/1.73m2); Data shown in figure from all participants, irrespective of whether participants lost glycemic control.

At baseline, 0.8% of participants had both hyperfiltration and increased albumin excretion, and 4.0% had both at year 5. Baseline eGFR was not associated with development of increased albumin excretion, nor was baseline ln(ACR) associated with risk of hyperfiltration.

In contrast to what was observed in the entire cohort (Table S1), when examined only in participants who remained in glycemic control, prevalence of hyperfiltration and elevated albumin excretion did not significantly increase over time (Table S2).

Associations between eIS and development of hyperfiltration

Lower log eIS was associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of hyperfiltration in a univariate model (Table 2), corresponding to an 8% increase in risk of hyperfiltration per 10% lower eIS. This association remained significant in the adjusted model (Table 3). HbA1c, BMI, age, loss of glycemic control, development of hypertension, nor treatment group were associated with increased risk of developing hyperfiltration in the adjusted model. However, male sex was associated with decreased risk of developing hyperfiltration (p=0.03, Table 3). In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for ACE-I/ARB use instead of development of hypertension in the multivariable model, and the association between eIS and incident hyperfiltration remained statistically significant (HR, 2.05; 95% CI, 1.11–3.79; p=0.02). Due to concerns of collinearity between HbA1c and loss of glycemic control, we also reran the multivariable model without HbA1c, and loss of glycemic control conferred greater risk of hyperfiltration (HR, 3.49; 95% CI, 1.43–8.47; p=0.006).

Table 2.

Univariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model predicting hyperfiltration or increased albumin excretion

| Hyperfiltration | Increased albumin excretion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| ln(estimated insulin sensivity), per 1-U lower | 2.12 (1.22–3.68) | 0.008 | 1.25 | 0.86–1.82 | 0.2 | |

| Δ in ln(estimated insulin sensivity), per 1-U decrease | 1.87 | 1.19–2.94 | 0.006 | 0.82 | 0.57–1.17 | 0.3 |

| Male sex | 0.32 | 0.11–0.91 | 0.03 | 1.12 | 0.68–1.86 | 0.6 |

| Baseline age, per 1-y higher | 0.89 | 0.73–1.09 | 0.2 | 1.07 | 0.95–1.22 | 0.3 |

| Hispanic race-ethnicity* | 1.79 | 0.80–3.97 | 0.1 | 1.29 | 0.79–2.11 | 0.3 |

| Non-Hispanic black race-ethnicity* | 0.49 | 0.18–1.31 | 0.1 | 0.84 | 0.49–1.44 | 0.5 |

| Other race-ethnicity | 2.48 | 0.57–10.9 | 0.2 | 0.46 | 0.06–3.42 | 0.4 |

| Metformin+rosiglitazone** | 1.19 | 0.52–2.71 | 0.7 | 1.26 | 0.76–2.09 | 0.4 |

| Meftormin+intensive lifestyle** | 0.93 | 0.40–2.18 | 0.9 | 0.65 | 0.38–1.13 | 0.1 |

| BMI, per 1 kg/m2 higher | 0.98 | 0.93–1.03 | 0.4 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.04 | 0.3 |

| Δ in BMI, per 1 kg/m2 increase | 0.96 | 0.83–1.10 | 0.5 | 0.98 | 0.91–1.07 | 0.7 |

| HbA1c, per 1% lower | 1.21 | 1.05–1.39 | 0.01 | 1.38 | 1.36–1.51 | <0.001 |

| Δ in HbA1c, per 1% decrease | 1.23 | 1.05–1.43 | 0.008 | 1.41 | 1.29–1.55 | <0.001 |

| Loss of glycemic control | 3.31 | 1.47–7.43 | 0.004 | 4.37 | 2.57–7.43 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension diagnosis | 1.56 | 0.70–3.48 | 0.3 | 2.02 | 1.22–3.35 | 0.006 |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Δ: change from baseline.

Referent group: Non-Hispanic White.

referent group: metformin only.

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model predicting hyperfiltration or increased albumin excretion

| Hyperfiltration | Increased albumin excretion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Δ in ln(estimated insulin sensivity), per 1-U decrease | 2.13 | 1.16–4.00 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.68–1.49 | 0.9 |

| Male | 0.32 | 0.11–0.91 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.50–1.56 | 0.7 |

| Baseline age, per 1-y higher | 0.93 | 0.75–1.17 | 0.5 | 1.00 | 0.87–1.15 | 0.9 |

| Hispanic race-ethnicity* | 1.38 | 0.43–4.42 | 0.6 | 1.00 | 0.48–2.09 | 0.9 |

| Non-Hispanic black race- ethnicity* | 0.51 | 0.13–2.06 | 0.3 | 0.55 | 0.24–1.25 | 0.1 |

| Other race-ethnicity | 2.14 | 0.36–12.9 | 0.4 | 0.70 | 0.09–5.65 | 0.7 |

| Metformin+rosiglitazone** | 1.47 | 0.54–4.04 | 0.4 | 1.20 | 0.65–2.22 | 0.5 |

| Meftormin+intensive lifestyle** | 1.14 | 0.41–3.22 | 0.8 | 0.66 | 0.33–1.31 | 0.2 |

| BMI, per 1 kg/m2 higher | 0.95 | 0.89–1.02 | 0.1 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.05 | 0.4 |

| HbA1c, per 1% lower | 1.05 | 0.82–1.34 | 0.7 | 1.36 | 1.18–1.57 | <0.001 |

| Loss of glycemic control | 2.92 | 0.80–10.7 | 0.1 | 1.47 | 0.64–3.40 | 0.4 |

| Hypertension diagnosis | 1.93 | 0.80–4.66 | 0.1 | 1.70 | 0.95–3.05 | 0.07 |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Referent group: Non-Hispanic White.

referent group: metformin only.

Associations between change in eIS and development of hyperfiltration

A 10% worsening of eIS relative to baseline was associated with a 7% percent increase in hyperfiltration in unadjusted (Table 2) and adjusted models (Table 4). Neither change in HbA1c nor change in BMI from baseline was associated with increased risk of developing hyperfiltration. When we adjusted for ACE-I/ARB use instead of hypertension diagnosis in the multivariable model, the relationship between change in eIS and incident hyperfiltration was of borderline statistical significance (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.00–2.35; p=0.05).

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model predicting hyperfiltration or increased albumin excretion

| Hyperfiltration | Increased albumin excretion | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Δ in ln(estimated insulin sensivity), per 1-U decrease | 1.59 | 1.04–2.44 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 0.58–1.18 | 0.3 |

| Male | 0.30 | 0.11–0.87 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.49–1.54 | 0.6 |

| Baseline age, per 1-y higher | 0.88 | 0.72–1.09 | 0.2 | 1.03 | 0.90–1.18 | 0.7 |

| Hispanic race-ethnicity* | 1.34 | 0.42–4.26 | 0.6 | 1.01 | 0.48–2.11 | 0.9 |

| Non-Hispanic black race-ethnicity* | 0.54 | 0.14–2.10 | 0.4 | 0.56 | 0.25–1.28 | 0.2 |

| Other race-ethnicity | 2.23 | 0.37–13.5 | 0.4 | 0.66 | 0.08–5.33 | 0.7 |

| Metformin+rosiglitazone** | 1.34 | 0.49–3.67 | 0.6 | 1.14 | 0.62–2.12 | 0.7 |

| Meftormin+intensive lifestyle** | 0.96 | 0.34–2.71 | 0.9 | 0.64 | 0.32–1.27 | 0.2 |

| Δ in BMI, per 1 kg/m2 increase | 0.94 | 0.80–1.10 | 0.4 | 1.08 | 0.99–1.18 | 0.1 |

| Δ in HbA1c, per 1% decrease | 1.12 | 0.88–1.41 | 0.3 | 1.39 | 1.20–1.60 | <0.001 |

| Loss of glycemic control | 2.42 | 0.75–7.82 | 0.1 | 1.95 | 0.90–4.24 | 0.09 |

| Hypertension diagnosis | 1.95 | 0.83–4.57 | 0.1 | 1.89 | 1.08–3.31 | 0.03 |

HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Referent group: Non-Hispanic White.

referent group: metformin only.

Associations between eIS and development of increased albumin excretion

Neither log eIS, BMI, age, loss of glycemic control, development of hypertension nor treatment group were associated with increased risk of developing increased albumin excretion in univariate (Table 2) or multivariable (Table 3) models. However as previously reported (3), 1% greater HbA1c was associated with increased risk of incident increased albumin excretion in adjusted models (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.18–1.57; p<0.001) (Table 3).

Associations between change in eIS and development of increased albumin excretion

Neither change in log eIS (Table 2) nor change in BMI from baseline to the time of increased albumin excretion were associated with increased risk of developing increased albumin excretion in unadjusted or adjusted models (Table 4). However, change in HbA1c from baseline and hypertension diagnosis were associated with increased risk of increased albumin excretion (Table 4).

Discussion

Adolescents with T2D in the TODAY study overall demonstrated a rise in eGFR, increased albumin excretion, and a decline in eIS over time. Lower eIS and female sex were clearly associated with incident hyperfiltration over the study period, independent of other risk factors. Conversely, increased albumin excretion was not associated with eIS over time, but was related to glycemic control and hypertension. These findings suggest that worsening insulin resistance confers increased risk for hyperfiltration in youth-onset T2D, and that hyperfiltration and increased albumin excretion may be associated with discrete risk factors reflecting their underlying pathophysiology.

Adolescents with T2D are at especially high risk of developing kidney disease, with up to 45% progressing to kidney failure as adults, which is significantly greater than youth with type 1 diabetes and adults with adult-onset T2D (14,15). The natural history of DKD features an extended silent period during which overt clinical signs or symptoms of kidney disease are absent. For this reason, a substantial challenge in efforts to prevent DKD is how difficult it is to accurately identify high-risk patients with pre-clinical disease. Therefore, American Diabetes Association now recommends assesssing eGFR in adolescents with T2D annually (27) to screen for DKD. There is a shortage of longitudinal eGFR data in youth-onset T2D. The reports on eGFR and hyperfiltration in this study provide clinicians with reference data from a large national study of youth with T2D. To our knowledge, this report is also one of the first to demonstrate a longitudinal relationship between eIS and hyperfiltration in adolescents with T2D; it also shows a longitudinal relationship between HbA1c and increased albumin excretion in this population. Moreover, IS was more predictive of hyperfiltration than conventional risk factors for the development of kidney disease, including glycemic control, BMI, and hypertension. These observations are similar to the previous cross-sectional report by Bjornstad, et al (2) demonstrating an independent association of IS and GFR in adolescents with T2D.

Hyperfiltration is a distinct, preclinical phenotype of DKD that is predictive of subsequent development of increased albumin excretion and progression of diabetic nephropathy (28,29). Hyperfiltration is proposed to reflect an underlying increase in intraglomerular pressure, leading to structural changes (mesangial expansion and glomerular basement membrane thickening) over time (30). The mechanisms believed to underlie these pathological changes are complex, involving growth factors, neurohormonal activation, and alterations in renal tubuloglomerular feedback (31). Accumulating evidence has shown that insulin resistance is associated with an increase in glomerular hydrostatic pressure, leading to increased renal vascular permeability and eventually glomerular hyperfiltration (32–36).

The association between insulin resistance and progression of increased albumin excretion in adults with T2D is increasingly accepted. Parvanova et al (37) reported a significant cross-sectional association between measured insulin resistance and increased albumin excretion in adults, while De Cosmo et al (38) found that adult men with HOMA-IR values in the highest quartile were more likely to have increased albumin excretion than those in the lowest quartile. Other researchers have demonstrated a longitudinal relationship between insulin resistance and incident increased albumin excretion over 5 years in adults (33). While we observed strong longitudinal relationships between IS and hyperfiltration, similar relationships were not demonstrated with increased albumin excretion. Conventional understanding is that hyperfiltration is a maladaptive glomerular response that precedes increased albumin excretion and subsequent decline of kidney function in diabetic nephropathy (39). Compared to adults, DKD in our adolescent cohort with short diabetes duration may be in its earliest stage of disease progression, and therefore before an association between insulin resistance and increased albumin excretion becomes apparent. Others have more recently proposed that hyperfiltration and increased albumin excretion, are in fact, distinct phenotypes of DKD (12), each with their own discrete pathogenic mechanisms. This hypothesis would be consistent with the observation that increased albumin excretion does not necessarily reflect progressive nephropathy and that increased albumin excretion may revert to normal albumin excretion in T2D (40), a fact that confounds longitudinal analyses. Data from SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth Study demonstrated a cross-sectional relationship between ACR and IS calculated by an equation consisting of waist circumference, triglycerides, and HbA1c in youth with T2D (19). Because HbA1c was incorporated into the equation used to calculate IS, HbA1c was not included in their multivariable models, and it is possible that the association demonstrated between calculated IS and ACR in SEARCH was driven by HbA1c rather than insulin resistance, consistent with the relationship we observed between HbA1c and elevated albumin excretion. Another explanation for the discrepancy is longer duration of diabetes in the SEARCH population.

Since IS can be modified by changes in lifestyle (such as diet and exercise) and medications (e.g. metformin), IS may be a promising therapeutic target to reduce DKD in adolescents with T2D. In adults with coronary artery disease and T2D (41), BARI-2D (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation in Type 2 Diabetes) insulin-sensitizing therapy had no benefit on progression of DKD. However, this study population was significantly different than the TODAY cohort, with a mean participant age of 62 years and most participants already having hypertension and hyperlipidemia at baseline (42). The kidney injury in longstanding DKD may be less responsive to changes in IS than the early alterations in kidney function observed in adolescents with T2D, arguing for separate studies in youth. Moreover, since signs of DKD are already detectable in youth with T2D, early interventions are likely needed to prevent further progression of DKD. Our supplemental data also suggest a lower prevalence of DKD in those participants who did not experience progressive β-cell failure and remained in glycemic control.

Our study does have limitations, including the use of calculated GFR (eGFR) and estimated IS (eIS). Although gold standard measurements are preferable, these would have presented an unreasonable burden to an already challenged group of TODAY study subjects. Moreover, the reciprocal of fasting insulin has demonstrated strong agreement with IS measured by hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp studies (43,44). While there are several pediatric eGFR equations, none have been validated against measured GFR in obese adolescents with T2D. We decided to calculate eGFR by the Zappitelli combined creatinine and cystatin C equation as it has shown accuracy in estimating GFR in adolescents with GFR in the normal to elevated range (45). Because our definition of hyperfiltration required elevated GFR at three consecutive annual visits, participants who had eGFR ≥140mL/min/1.73m2 at year 4 and 5, or only year 5 were not categorized as having hyperfiltration as data beyond year 5 were not available for these analyses. This conservative definition of hyperfiltration may underestimate the number of participants with hyperfiltration in our analyses and therefore may bias the results towards the null hypotheses. Our definition of hyperfiltration is based on NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey)26 rather than a supraphysiological rise in each participant baseline GFR before the onset of T2D, which would have been ideal. Furthermore, longer follow-up is likely required to capture the transition from hyperfiltration to rapid GFR decline. Even though basic and clinical research studies imply that IS has direct effects on kidney health, underlying common risk factors that are responsible for both worsening IS and renal pathology could be an alternative explantion. The strengths of our study include the large number of participants and the availability of longitudinal data at several time points not only for eIS and eGFR, but also for other important covariates (e.g., HbA1c, and BMI and hypertension), which allowed us to examine the independent relationship between eIS and incident hyperfiltration.

In summary, the high rates of increased albumin excretion and hyperfiltration in youth with T2D forecast early renal morbidity and mortality. Improved understanding of the determinants of DKD risk and progression over longer periods of follow-up is essential to improve outcomes in youth with T2D. We found that insulin resistance rather than adiposity, blood pressure, or glycemic control was associated with greater risk of hyperfiltration over the 5-year study period in adolescents with T2D. Worsening IS may therefore represent an early risk factor for future progression of DKD in adolescents with T2D.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Means (eGFR, ACR, estimated insulin sensitivity) and point prevalences (elevated eGFR, increased ACR, and hyperfiltration) over 5-y study duration.

Table S2: Means (eGFR, ACR, estimated insulin sensitivity) and point prevalences (elevated eGFR, increased ACR, and hyperfiltration) over 5-y study duration, while participants still in glycemic control.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was completed with funding from NIDDK/NIH grant numbers T32-DK063687, U01-DK61212, U01-DK61230, U01-DK61239, U01-DK61242, and U01-DK61254; from the National Center for Research Resources General Clinical Research Centers Program grant numbers M01-RR00036 (Washington University School of Medicine), M01-RR00043-45 (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles), M01-RR00069 (University of Colorado Denver), M01-RR00084 (Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh), M01-RR01066 (Massachusetts General Hospital), M01-RR00125 (Yale University), and M01-RR14467 (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center); and from the NCRR Clinical and Translational Science Awards grant numbers UL1-RR024134 (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia), UL1-RR024139 (Yale University), UL1-RR024153 (Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh), UL1-RR024989 (Case Western Reserve University), UL1-RR024992 (Washington University in St Louis), UL1-RR025758 (Massachusetts General Hospital), and UL1-RR025780 (University of Colorado Denver). NIDDK had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; and in writing the report. Drug and supplies donations in support of the study’s efforts were received from Becton, Dickinson and Company; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Eli Lilly and Company; GlaxoSmithKline; LifeScan, Inc.; Pfizer; Sanofi Aventis. None of these companies had any role in any aspect of the study.

We gratefully acknowledge the participation and guidance of the American Indian partners associated with the clinical center located at the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, including members of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe, Cherokee Nation, Chickasaw Nation, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and Oklahoma City Area Indian Health Service.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: Contributed to study design: PB, EN, SA, KJN; data acquisition: PB, FB, SM, SMW, LL, SA, KJN; data analysis/interpretation: PB, EN, LE, FB, IML, SM, SA, KJN, SMW, LL; statistical analysis: LE. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no other relevant financial interests.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the respective Tribal and Indian Health Service Institution Review Boards or their members.

Peer Review: Received _______. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, a Statistics/Methods Editor, and an Acting Editor-in-Chief (Associate Editor James S. Kaufman, MD). Accepted in revised form on _______. The involvement of an Acting Editor-in-Chief to handle the peer-review and decision-making processes was to comply with AJKD’s procedures for potential conflicts of interest for editors, described in the Information for Authors & Journal Policies.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Herzog C, et al. US Renal Data System 2010 Annual Data Report. American journal of kidney diseases: the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2011;57(1 Suppl 1):A8e1–526. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjornstad P, Maahs DM, Cherney DZ, et al. Insulin sensitivity is an important determinant of renal health in adolescents with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(11):3033–9. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapid rise in hypertension and nephropathy in youth with type 2 diabetes: the TODAY clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1735–41. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alleyn CR, Volkening LK, Wolfson J, Rodriguez-Ventura A, Wood JR, Laffel LM. Occurrence of microalbuminuria in young people with Type 1 diabetes: importance of age and diabetes duration. Diabet Med. 2010;27(5):532–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02983.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eppens MC, Craig ME, Cusumano J, et al. Prevalence of diabetes complications in adolescents with type 2 compared with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(6):1300–6. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiess W, Bottner A, Bluher S, Raile K, Galler A, Kapellen TM. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents--the beginning of a renal catastrophe? Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2004;19(11):2693–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Design, implementation, and preliminary results of a long-term follow-up of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial cohort. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(1):99–111. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yokoyama H, Okudaira M, Otani T, et al. Existence of early-onset NIDDM Japanese demonstrating severe diabetic complications. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(5):844–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.5.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokoyama H, Okudaira M, Otani T, et al. High incidence of diabetic nephropathy in early-onset Japanese NIDDM patients. Risk analysis. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(7):1080–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.7.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez BL, Dabelea D, Liese AD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of elevated blood pressure in youth with diabetes mellitus: the SEARCH for diabetes in youth study. J Pediatr. 2010;157(2):245–51. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drummond K, Mauer M. The early natural history of nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: II. Early renal structural changes in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51(5):1580–7. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bjornstad P, Cherney DZ, Maahs DM, Nadeau KJ. Diabetic Kidney Disease in Adolescents With Type 2 Diabetes: New Insights and Potential Therapies. Current diabetes reports. 2016;16(2):11. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0708-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lytvyn Y, Bjornstad P, Pun N, Cherney DZ. New and old agents in the management of diabetic nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2016 May;25(3):232–9. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Retnakaran R, Cull CA, Thorne KI, Adler AI, Holman RR. Risk factors for renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: U.K. Prospective Diabetes Study 74. Diabetes. 2006;55(6):1832–9. doi: 10.2337/db05-1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Muntner P, Hamm LL, et al. Insulin resistance and risk of chronic kidney disease in nondiabetic US adults. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. 2003;14(2):469–77. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000046029.53933.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Satriano J, Thomas JL, Miyamoto S, Sharma K, Pastor-Soler NM, Hallows KR, Singh P. Interactions between HIF-1α and AMPK in the regulation of cellular hypoxia adaptation in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015 Sep 1;309(5):F414–28. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00463.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyamoto S, Hsu CC, Hamm G, Darshi M, Diamond-Stanic M, Declèves AE, Slater L, Pennathur S, Stauber J, Dorrestein PC, Sharma K. Mass Spectrometry Imaging Reveals Elevated Glomerular ATP/AMP in Diabetes/obesity and Identifies Sphingomyelin as a Possible Mediator. EBioMedicine. 2016 May;7:121–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrier RW, Harris DC, Chan L, Shapiro JI, Caramelo C. Tubular hypermetabolism as a factor in the progression of chronic renal failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 1988 Sep;12(3):243–9. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(88)80130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mottl AK, Divers J, Dabelea D, et al. The dose-response effect of insulin sensitivity on albuminuria in children according to diabetes type. Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31(6):933–40. doi: 10.1007/s00467-015-3276-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeitler P, Epstein L, Grey M, et al. Treatment options for type 2 diabetes in adolescents and youth: a study of the comparative efficacy of metformin alone or in combination with rosiglitazone or lifestyle intervention in adolescents with type 2 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2007;8(2):74–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prigent A. Monitoring renal function and limitations of renal function tests. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 2008;38(1):32–46. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.TODAY Study Group. A clinical trial to maintain glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes. N Eng J Med. 2012;366(24):2247–2256. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.George L, Bacha F, Lee S, Tfayli H, Andreatta E, Arslanian S. Surrogate estimates of insulin sensitivity in obese youth along the spectrum of glucose tolerance from normal to prediabetes to diabetes. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2011;96(7):2136–45. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacha F, Pyle L, Nadeau K, et al. Determinants of glycemic control in youth with type 2 diabetes at randomization in the TODAY study. Pediatric diabetes. 2012;13(5):376–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bacchetta J, Cochat P, Rognant N, Ranchin B, Hadj-Aissa A, Dubourg L. Which creatinine and cystatin C equations can be reliably used in children? Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2011;6(3):552–60. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04180510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fadrowski JJ, Neu AM, Schwartz GJ, Furth SL. Pediatric GFR estimating equations applied to adolescents in the general population. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2011;6(6):1427–35. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06460710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Diabetes Association. 10. Microvascular Complications and Foot Care. Diabetes Care. 2017 Jan;40(Suppl 1):S88–S98. doi: 10.2337/dc17-S013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amin R, Turner C, van Aken S, et al. The relationship between microalbuminuria and glomerular filtration rate in young type 1 diabetic subjects: The Oxford Regional Prospective Study. Kidney international. 2005;68(4):1740–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Magee GM, Bilous RW, Cardwell CR, Hunter SJ, Kee F, Fogarty DG. Is hyperfiltration associated with the future risk of developing diabetic nephropathy? A meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2009;52(4):691–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Remuzzi G, Benigni A, Remuzzi A. Mechanisms of progression and regression of renal lesions of chronic nephropathies and diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(2):288–96. doi: 10.1172/JCI27699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cherney DZ, Scholey JW, Miller JA. Insights into the regulation of renal hemodynamic function in diabetic mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2008;4(4):280–90. doi: 10.2174/157339908786241151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dart AB, Sellers EA, Martens PJ, Rigatto C, Brownell MD, Dean HJ. High burden of kidney disease in youth-onset type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1265–71. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu CC, Chang HY, Huang MC, et al. Association between insulin resistance and development of microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):982–7. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Catalano C, Muscelli E, Quinones Galvan A, et al. Effect of insulin on systemic and renal handling of albumin in nondiabetic and NIDDM subjects. Diabetes. 1997;46(5):868–75. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.5.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen AJ, McCarthy DM, Stoff JS. Direct hemodynamic effect of insulin in the isolated perfused kidney. Am J Physiol. 1989;257(4 Pt 2):F580–5. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.4.F580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tucker BJ, Anderson CM, Thies RS, Collins RC, Blantz RC. Glomerular hemodynamic alterations during acute hyperinsulinemia in normal and diabetic rats. Kidney international. 1992;42(5):1160–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parvanova AI, Trevisan R, Iliev IP, et al. Insulin resistance and microalbuminuria: a cross-sectional, case-control study of 158 patients with type 2 diabetes and different degrees of urinary albumin excretion. Diabetes. 2006;55(5):1456–62. doi: 10.2337/db05-1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Cosmo S, Minenna A, Ludovico O, et al. Increased urinary albumin excretion, insulin resistance, and related cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence of a sex-specific association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):910–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okada R, Yasuda Y, Tsushita K, Wakai K, Hamajima N, Matsuo S. Glomerular hyperfiltration in prediabetes and prehypertension. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2012;27(5):1821–5. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamada T, Komatsu M, Komiya I, et al. Development, progression, and regression of microalbuminuria in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes under tight glycemic and blood pressure control: the Kashiwa study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2733–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.August P, Hardison RM, Hage FG, et al. Change in albuminuria and eGFR following insulin sensitization therapy versus insulin provision therapy in the BARI 2D study. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2014;9(1):64–71. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12281211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baseline characteristics of patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease enrolled in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) trial. Am Heart J. 2008;156(3):528–36. 36e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muniyappa R, Lee S, Chen H, Quon MJ. Current approaches for assessing insulin sensitivity and resistance in vivo: advantages, limitations, and appropriate usage. American journal of physiology Endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;294(1):E15–26. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00645.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burns SF, Bacha F, Lee SJ, Tfayli H, Gungor N, Arslanian SA. Declining beta-cell function relative to insulin sensitivity with escalating OGTT 2-h glucose concentrations in the nondiabetic through the diabetic range in overweight youth. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(9):2033–40. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharma AP, Yasin A, Garg AX, Filler G. Diagnostic accuracy of cystatin C-based eGFR equations at different GFR levels in children. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2011;6(7):1599–608. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10161110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Means (eGFR, ACR, estimated insulin sensitivity) and point prevalences (elevated eGFR, increased ACR, and hyperfiltration) over 5-y study duration.

Table S2: Means (eGFR, ACR, estimated insulin sensitivity) and point prevalences (elevated eGFR, increased ACR, and hyperfiltration) over 5-y study duration, while participants still in glycemic control.