Abstract

Background

Even though the caesarean section is an essential component of comprehensive obstetric and newborn care for reducing maternal and neonatal mortality, there is a lack of data regarding caesarean section rates, its determinants and health outcomes among tribal communities in India.

Objective

The aim of this study is to estimate and compare rates, determinants, indications and outcomes of caesarean section. The article provides an assessment on how the inequitable utilization can be addressed in a community-based hospital in tribal areas of Gujarat, India.

Method

Prospectively collected data of deliveries (N = 19923) from April 2010 to March 2016 in Kasturba Maternity Hospital was used. The odds ratio of caesarean section was estimated for tribal and non-tribal women. Decomposition analysis was done to decompose the differences in the caesarean section rates between tribal and non-tribal women.

Results

The caesarean section rate was significantly lower among tribal compared to the non-tribal women (9.4% vs 15.6%, p-value < 0.01) respectively. The 60% of the differences in the rates of caesarean section between tribal and non-tribal women were unexplained. Within the explained variation, the previous caesarean accounted for 96% (p-value < 0.01) of the variation. Age of the mother, parity, previous caesarean and distance from the hospital were some of the important determinants of caesarean section rates. The most common indications of caesarean section were foetal distress (31.2%), previous caesarean section (23.9%), breech (16%) and prolonged labour (11.2%). There was no difference in case fatality rate (1.3% vs 1.4%, p-value = 0.90) and incidence of birth asphyxia (0.3% vs 0.6%, p-value = 0.26) comparing the tribal and non-tribal women.

Conclusion

Similar to the prior evidences, we found higher caesarean rates among non-tribal compare to tribal women. However, the adverse outcomes were similar between tribal and non-tribal women for caesarean section deliveries.

Introduction

The maternal and neonatal health outcomes among tribal and indigenous communities are worse compared to non-tribal populations in low-middle income countries [1–2]. The availability of comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care (CEmONC) is inequitable in low resource settings such as remote rural and tribal areas [3–5]. Hence, providing CEmONC can improve maternal and neonatal health in tribal regions [4]. One of the essential components of CEmONC is the delivery of a foetus through a caesarean section. Caesarean section, when indicated, can reduce maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity [5–7]. Some of the common, life-threatening indications for a caesarean section are obstructed labour, selected breech delivery, mal-presentation of the foetus and foetal distress [7]. Investing in the caesarean section is also found to be cost-effective [8]. The World Health Organization (WHO) earlier recommended around 5–15% rate of caesarean section in any population [6,9]. However, WHO recently suggested that they do not recommend a specific rate at either a country-level or a hospital-level [10]. Tribal population accounts for 8.4% (104 million) of the total population of India [11]. The overall rate of caesarean section delivery in 2015–16 is around 17.2% in India, increased from 8.5% in 2005–06 [12,13]. However, the caesarean section rate is estimated to be low in rural areas (12.9%) [12]. Lack of availability of emergency obstetric services, knowledge and financial constraint are some of the important factors for low caesarean section rate among rural tribal women [14–16]. In recent times, the incidences of caesarean section are on a rise in India [12, 17–19]. It would be important to study whether the increase in trend of caesarean section is equitable comparing the tribal to non-tribal communities. Additionally, the results of implementing the practices to limit the increasing rates of caesarean needs to be described.

The clinical indications of caesarean section among rural tribal women have not been studied in India. In general, there is a lack of data on indications and outcomes of caesarean section among tribal communities [6–7]. As the institutional deliveries and caesarean section are increasing, there is a need for better understanding of indication and outcomes of caesarean section [19]. The information on the indications of the caesarean section will be useful to clinicians, and public health practitioners in improving maternal health outcomes in tribal regions in India and countries with similar needs [7, 19]. Other condition such as sickle cell disease found predominantly among tribal women is also a risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes [20]. It will be crucial to compare the outcomes between tribal and non-tribal women with caesarean and vaginal deliveries. There are studies reported negative or no influences of caesarean on perinatal mortality in low-middle income countries where the caesarean rates are high [21–22]. There are also possible benefits of caesarean in settings where the caesarean rates are very low, due to unavailability of caesarean when needed [21–23]. This study reports the analyses of maternal admissions in the community-based hospital of SEWA-Rural (Kasturba Maternity Hospital) providing tribal-friendly CEmONC services in the Jhagadia block of Bharuch district, Gujarat. The objective of this study is to estimate rates, indications, determinants, and outcomes of caesarean section comparing tribal and non-tribal women in the context of a tribal friendly hospital providing CEmONC.

Data and methods

We used the data of all women who delivered at the Kasturba Maternity Hospital (KMH), a hospital managed by SEWA Rural, a voluntary, not-for-profit organization. KMH has been providing maternal and neonatal health services in this area since 1980 along with community-based services in surrounding areas [24]. The hospital functions in Jhagadia block of Bharuch in the western Indian state of Gujarat. The total population of Jhagadia block is around 185,000, of which 70% is tribal [11]. The hospital provides free clinical services to pregnant women and newborns. The hospital works as a first referral unit and is the largest provider of maternal health care in the Bharuch district and nearby areas.

The study is based on secondary analyses of data which was primarily collected for delivery and monitoring of services at the hospital. The data is part of the hospital program to provide quality health services to the remote and tribal areas of Gujarat. The ethical approval for the use of this data has been obtained from SEWA Rural Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC). The SEWA Rural IEC reviewed this data and allowed its use for analyses and publication. The IEC have also waived the need for the informed consent of the patient, given that the anonymity of the patient will be maintained. Any personal information of the patient was removed from the datasets before analysis.

Study setting

We used the data of all women who delivered at the Kasturba Maternity Hospital (KMH), a hospital managed by SEWA Rural, a voluntary, not-for-profit organization. KMH has been providing maternal and neonatal health services in this area since 1980 along with community-based services in surrounding areas [24]. The hospital functions in Jhagadia block of Bharuch in the western Indian state of Gujarat. The total population of Jhagadia block is around 185,000, of which 70% is tribal [11]. The hospital provides free clinical services to pregnant women and newborns. The hospital works as a first referral unit and is the largest provider of maternal health care in the Bharuch district and nearby areas.

The tribal population native to the study area is known as Vasava, and belongs to the Bhil tribe. As with other tribal communities, Vasava tribe has its own language and customs which are different from the mainstream culture; though this is changing as they are increasingly connected with the mainstream culture. Agriculture is the primary occupation with a large percentage of the population working as landless labourers [25].

KMH is a 200-bed tribal-friendly first referral unit providing CEmONC care to surrounding villages. The CEmONC services at the hospital include services from full-time clinicians including obstetricians, anaesthetists and internists. Along with the clinician, the hospital has a functional operation theatre, blood storage centre, ultrasound, and inpatient facility [24]. The mission of the hospital is to serve the most underprivileged tribal patients. Therefore, it is an empanelled provider for the government sponsored health insurance schemes to facilitate almost free or highly subsidized services to the poor.

Data sources and sample size

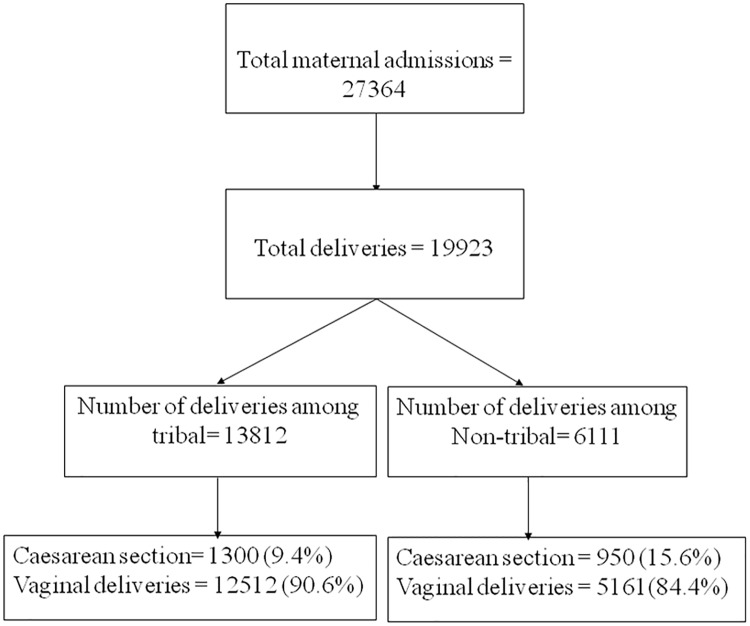

The hospital maintains a prospective registry for all admissions that is maintained by care providers and subsequently digitized by trained staff. A team of care providers including gynaecologists ensured the accuracy of the entire dataset, including that of indications and outcomes of all deliveries. Women who delivered from April 2010 to March 2016 were included in the study. The definition of tribal is as per the specifications from the government of India [26]. The description of admission and outcomes is shown in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Number of deliveries and caesarean sections in KMH (2010–16), Bharuch, Gujarat.

Independent and dependent variables

The deliveries were categorized as caesarean section and vaginal deliveries, and are the primary dependent variables. The potential determinants of caesarean section were maternal age, parity, maternal education, gestational week, haemoglobin status, government scheme, distance from the health facility and child’s gender. The adverse outcomes of deliveries examined for this analyses were still birth, low birth weight (less than 5.5 lbs/2500 grams), survival status of the neonate at the time of discharge from the hospital (case fatality rate) and birth asphyxia (no cry after delivery).

Statistical analyses

Rate, indication and outcomes of caesarean section were represented by percentages and counts comparing tribal and non-tribal women. Still birth rate and neonatal death rate are expressed per 1000 total (live + still) deliveries and per 1000 live births respectively. Logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio caesarean section by background characteristics as potential determinants. The odds ratio was adjusted for Mother’s age, Mother’s education, Parity, Mother’s haemoglobin, Gestational week, Child’s gender, Number of ANC visits by mother and Distance from the health facility. The odds ratio of caesarean section was estimated for tribal and non-tribal women. Decomposition analysis was done to decompose the differences in the rates of caesarean section between tribal and non-tribal women. Fairline modification of Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for the logit models was used [27]. Various indications for caesarean section among tribal women were compared with non-tribal women. The odds ratio of each pregnancy outcome of caesarean section and vaginal deliveries was calculated. The odds ratios were separately calculated for caesarean section and vaginal deliveries comparing tribal and non-tribal women. All of the odds ratios were reported with 95% confidence interval. Strobe guidelines were followed for reporting the results. Microsoft Excel 2007 was used to compile the data and STATA Version 12.0 was used for statistical analyses [28].

Results

The total number of deliveries were 19923 (tribal = 13812, non-tribal = 6111). The number of vaginal deliveries and those via caesarean section by ethnicity are given in Fig 1. Socioeconomic and other important characteristics of women delivered in the hospital are given in Table 1. Educational attainment was higher among non tribal women. Anaemia was higher among tribal women compared to non tribal women. A higher percentage of non-tribal women were coming from areas more than 100 kilometres away from the hospital compared to tribal women. Still births, low birth weight and no cry at birth were significantly higher among tribal women compared to non-tribal women.

Table 1. Socioeconomic and clinical characteristics of tribal and non-tribal women in KMH (2010–16), Bharuch, Gujarat.

| Tribal (N = 13812 deliveries) | Non Tribal (N = 6111 deliveries) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Mother’s age | 15–19 | 672 | 4.9 | 194 | 3.2 | 0.000 |

| 20–24 | 9,992 | 72.4 | 3,735 | 61.1 | ||

| 25–29 | 2,511 | 18.2 | 1,666 | 27.3 | ||

| 30 and above | 635 | 4.6 | 514 | 8.4 | ||

| Mother’s education | No education | 2,584 | 18.8 | 867 | 14.2 | 0.000 |

| 1–7 years | 5,795 | 42.1 | 2,144 | 35.2 | ||

| 8–12 years | 5,059 | 36.8 | 2,707 | 44.4 | ||

| 12 years and more | 315 | 2.3 | 378 | 6.2 | ||

| Parity | 0 | 7,411 | 53.7 | 3,184 | 52.1 | 0.020 |

| 1 | 4,166 | 30.2 | 1,950 | 31.9 | ||

| 2 | 1,669 | 12.1 | 681 | 11.1 | ||

| 3 and above | 566 | 4.1 | 296 | 4.8 | ||

| Mother’s haemoglobin at delivery | <7.0 | 660 | 4.8 | 159 | 2.6 | 0.000 |

| 7.1–10.0 | 5,275 | 38.5 | 1,883 | 31.1 | ||

| 10.1–11.0 | 3,884 | 28.3 | 1,558 | 25.7 | ||

| >11.0 | 3,896 | 28.4 | 2,464 | 40.6 | ||

| Previous caesarean | No | 13,404 | 97.9 | 5,750 | 94.1 | 0.000 |

| Yes | 408 | 2.1 | 361 | 5.9 | ||

| Gestational week | <36 weeks | 2,439 | 17.7 | 749 | 12.3 | 0.000 |

| 37–42 weeks | 11,362 | 82.3 | 5,358 | 87.7 | ||

| >42 weeks | 11 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.1 | ||

| Child’s gender | Female | 6,560 | 47.5 | 2,945 | 48.2 | 0.364 |

| Male | 7,252 | 52.5 | 3,166 | 51.8 | ||

| Number of ANC visits | 0 | 1,064 | 7.7 | 474 | 7.8 | 0.219 |

| 1–2 | 6,810 | 49.4 | 2,936 | 48.1 | ||

| 3 and above | 5,903 | 42.8 | 2,691 | 44.1 | ||

| Distance from the health facility (in Kilometres) | 0–25 | 11,102 | 80.4 | 3,766 | 61.6 | 0.000 |

| 26–50 | 1,391 | 10.1 | 406 | 6.6 | ||

| 51–100 | 955 | 6.9 | 973 | 15.9 | ||

| >100 | 364 | 2.6 | 966 | 15.8 | ||

| Still Birth | No | 13,358 | 96.7 | 6,003 | 98.2 | 0.000 |

| Yes | 450 | 3.3 | 107 | 1.8 | ||

| Birth weight <2500 grams | No | 7,575 | 56.7 | 4,083 | 68.0 | 0.000 |

| Yes | 5,780 | 43.3 | 1,919 | 32.0 | ||

| Immediate cry at birth | No | 406 | 3.0 | 146 | 2.4 | 0.019 |

| Yes | 12,951 | 97.0 | 5,857 | 97.6 | ||

| Neonatal deaths at hospital | No | 13,341 | 99.9 | 5,990 | 99.8 | 0.114 |

| Yes | 17 | 0.1 | 13 | 0.2 | ||

Rates and determinants of caesarean rates among tribal and non tribal women

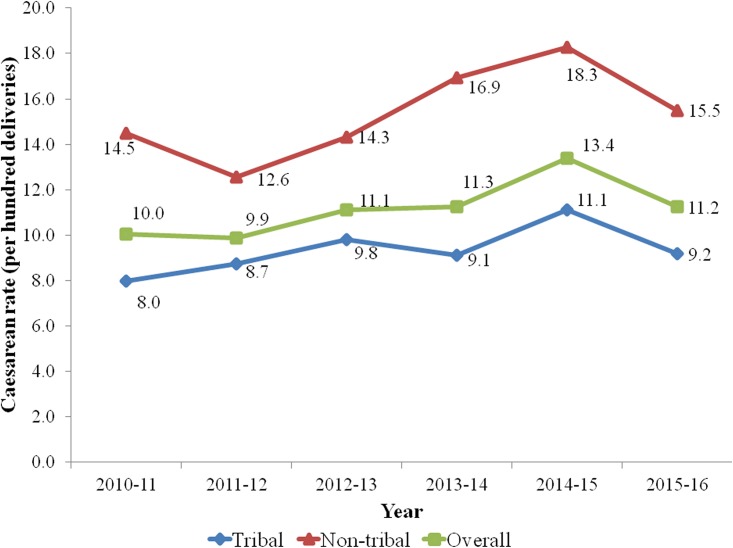

The caesarean section rates for tribal and non-tribal women were 9.4% (n = 1300) and 15.6% (n = 950) respectively (Fig 1). The gaps in caesarean section rates between tribal and non-tribal women were similar in the six year study timeframe (Fig 2). Our findings demonstrate an increasing trend of caesarean section rates in both tribal and non-tribal women. Overall, 14,539 (73%) out of total deliveries received the benefit of various government sponsored health insurance schemes and did not bear any out of pocket expenditure for delivery.

Fig 2. Annual caesarean rates (%) among tribal and non-tribal women in KMH (2010–16), Bharuch, Gujarat.

Increasing age of the mother was related to increasing caesarean section rates in tribal women (Table 2). Education was significantly associated with increasing caesarean among non tribal women. The odds ratio was significantly lower among women with parity 1 and above compared to women with zero parity in tribal and non tribal women alike. Gender of the child, gestational weeks and mother’s haemoglobin count were not significantly associated with caesarean section. The caesarean rate among women who had caesarean in the past was very high compared to women who did not have any previous caesarean. Tribal Women coming from areas in the range of 25–50 kilometres from the hospital have higher caesarean section rate compared to women coming from the areas less than 25 kilometres.

Table 2. Numbers and rates of caesarean section by selected determinants among tribal and non-tribal women.

| Tribal (N = 1300 caesarean deliveries) | Non tribal(N = 950 caesarean deliveries) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (Caesarean Rate*) | Adjusted odds ratio | P-value | Number (Caesarean Rate*) | Adjusted odds ratio | P-value | ||

| Overall | 1300(9.4) | 950(15.5) | |||||

| Mother’s age | 15–19 | 45(6.7) | 23(11.9) | ||||

| 20–24 | 880(8.8) | 1.39(1.01–1.90) | 0.043 | 547(14.6) | 1.26(0.80–1.98) | 0.323 | |

| 25–29 | 277(11.0) | 1.99(1.40–2.82) | 0.000 | 276(16.6) | 1.34(0.83–2.18) | 0.234 | |

| 30 and above | 98(15.4) | 3.32(2.19–5.03) | 0.000 | 103(20.0) | 1.69(0.98–2.94) | 0.061 | |

| Mother’s education | No education | 222(8.6) | 91(10.5) | ||||

| 1–7 years | 516(8.9) | 1.11(0.96–1.28) | 0.146 | 327(15.3) | 0.97(0.81–1.16) | 0.746 | |

| 8–12 years | 509(10.1) | 1.10(0.76–1.60) | 0.602 | 435(16.1) | 1.45(1.07–1.98) | 0.018 | |

| 12 years and more | 46(14.6) | 1.01(0.84–1.22) | 0.875 | 94(24.9) | 0.73(0.54–0.98) | 0.039 | |

| Parity | 0 | 728(9.8) | 493(15.5) | ||||

| 1 | 424(10.2) | 0.43(0.36–0.51) | 0.000 | 332(17.0) | 0.40(0.32–0.50) | 0.000 | |

| 2 | 107(6.4) | 0.31(0.24–0.40) | 0.000 | 95(14.0) | 0.37(0.26–0.52) | 0.000 | |

| 3 and above | 41(7.2) | 0.39(0.27–0.57) | 0.000 | 30(10.1) | 0.42(0.26–0.70) | 0.001 | |

| Mother’s haemoglobin at delivery | <7.0 | 61(9.2) | 17(10.7) | ||||

| 7.1–10.0 | 515(9.8) | 0.91(0.67–1.23) | 0.525 | 277(14.7) | 0.91(0.51–1.61) | 0.735 | |

| 10.1–11.0 | 337(8.7) | 0.74(0.54–1.01) | 0.060 | 207(13.3) | 0.74(0.42–1.33) | 0.321 | |

| >11.0 | 382(9.8) | 0.84(0.61–1.15) | 0.273 | 441(17.9) | 1.01(0.57–1.79) | 0.969 | |

| Gestational week | <36 weeks | 199(8.2) | 89(11.9) | ||||

| 37–42 weeks | 1099(9.7) | 1.17(0.98–1.39) | 0.078 | 859(16.0) | 1.14(0.88–1.49) | 0.325 | |

| >42 weeks | 2(18.2) | 1.94(0.32–11.89) | 0.473 | 2(50.0) | 7.98(0.97–65.74) | 0.054 | |

| Previous caesarean | No | 1016 (7.6) | 657 (11.4) | ||||

| Yes | 284 (69.6) | 44.7(34.74–57.51) | 0.000 | 293 (81.3) | 57.51(41.97–78.82) | 0.000 | |

| Child’s gender | Female | 599(9.1) | 429(14.6) | ||||

| Male | 701(9.7) | 1.10(0.97–1.24) | 0.144 | 521(16.5) | 1.16(0.98–1.36) | 0.076 | |

| Number of ANC visits | 0 | 117(11.0) | 45(9.5) | ||||

| 1–2 | 520(7.6) | 0.60(0.48–0.76) | 0.000 | 363(12.4) | 1.01(0.70–1.46) | 0.937 | |

| 3 and above | 663(11.2) | 0.91(0.72–1.16) | 0.465 | 542(20.1) | 1.67(1.16–2.41) | 0.006 | |

| Distance from the health facility (in Kilometres) | 0–25 | 975(8.8) | 577(15.3) | ||||

| 26–50 | 172(12.4) | 1.31(1.07–1.59) | 0.007 | 71(17.5) | 1.20(0.88–1.65) | 0.248 | |

| 51–100 | 112(11.7) | 1.25(1.00–1.58) | 0.055 | 169(17.4) | 1.28(1.03–1.59) | 0.026 | |

| >100 | 41(11.3) | 1.07(0.74–1.56) | 0.704 | 133(13.8) | 1.11(0.88–1.40) | 0.393 | |

*per 100 deliveries

Decomposition of caesarean section rates between tribal and non-tribal women

Decomposition analysis decomposed differences found between tribal and non-tribal women to other selected variables (Table 3). Overall 40% of variation was explained by the variables. Maternal age was responsible for about 15.4% of explained variation. Previous caesarean section was accounted for 96% of explained variation between tribal and non-tribal women. Parity also significantly explained the difference between tribal and non-tribal women. Distance from health facility accounted for 18% of explained variation, though it was non-significant.

Table 3. Results of decomposition analysis on caesarean rate between tribal and non-tribal women.

| Absolute difference | Percentage contribution to total differences | Percentage contribution to explained differences | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall difference in caesarean rates between tribal and non-tribal | 0.041 | 100.0 | ||

| Unexplained difference in caesarean rates between tribal and non-tribal | 0.025 | 60.0 | ||

| Explained difference in caesarean rates between tribal and non-tribal | 0.017 | 40.0 | 100.0 | |

| Mother’s age | 0.003 | 7.2 | 15.4 | 0.058 |

| Parity | -0.006 | -14.4 | -37.7 | 0.000 |

| Previous caesarean | 0.016 | 38.4 | 96.0 | 0.000 |

| Mother’s education | 0.000 | 0.0 | -1.0 | 0.335 |

| Haemoglobin status | 0.000 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.725 |

| Number of ANC visits | 0.000 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.338 |

| Distance from the health facility | 0.003 | 7.2 | 18.1 | 0.143 |

| Gender | 0.000 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.595 |

| Year | 0.001 | 2.4 | 4.1 | 0.061 |

Clinical indication of caesarean section

The most common indications for caesarean section were foetal distress followed by previous caesarean section and breech presentation (Table 4). Among non-tribal women, the most common indicators were the previous caesarean section, followed by foetal distress, breech and prolonged labour. Previous caesarean sections were significantly higher among non tribal women. Similarly, transverse lies were higher in tribal compared to non-tribal women. Pregnancy induced hypertension being the most common secondary indications for caesarean section in both tribal and non-tribal women.

Table 4. Primary and secondary indications for caesarean section.

| Tribal (N = 1300 Caesarean sections) | Non-tribal (N = 950 Caesarean sections) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | ||

| Primary indication | |||||

| Foetal distress | 406 | 31.2 | 291 | 30.6 | 0.761 |

| Previous Caesarean sections | 311 | 23.9 | 315 | 33.2 | 0.000 |

| Prolonged Labour | 145 | 11.2 | 115 | 12.1 | 0.486 |

| Breech | 208 | 16.0 | 116 | 12.2 | 0.011 |

| Transverse lie | 67 | 5.2 | 27 | 2.8 | 0.007 |

| Obstructed Labour | 32 | 2.5 | 16 | 1.7 | 0.208 |

| Placenta previa | 35 | 2.7 | 15 | 1.6 | 0.077 |

| Multiple births | 26 | 2.0 | 12 | 1.3 | 0.180 |

| Cephalopelvic disproportion | 24 | 1.8 | 11 | 1.2 | 0.193 |

| Placental abruption | 17 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.2 | 0.752 |

| Failed Medical induction of labour | 9 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.7 | 0.901 |

| Others | 100 | 7.7 | 80 | 8.4 | 0.582 |

| Secondary indication | |||||

| Pregnancy induced hypertension | 205 | 15.8 | 146 | 15.4 | 0.796 |

| Eclampsia | 62 | 4.8 | 32 | 3.4 | 0.101 |

| Sickle Cell disease | 37 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Anaemia | 75 | 5.8 | 39 | 4.1 | 0.075 |

| Oligohydramnios | 20 | 1.5 | 14 | 1.5 | 0.901 |

Outcomes of caesarean section deliveries

There was no difference in the case fatality rate among neonates comparing the tribal and non-tribal in caesarean section deliveries (Table 5). Percentage of no cry after birth was similar among tribal women in both caesarean section and vaginal deliveries. The percentage of the neonates who weighed less than 2.5 kilograms was also similar in caesarean section and vaginal deliveries. Percentage of neonates who weighed less than 2.5 kilograms was higher among tribal compared to non-tribal women. Still birth rate was lower in caesarean section deliveries. However, the difference between tribal and non-tribal was significant in both types of deliveries. Around 90% of women who had still birth had no foetal heart sound on admission suggesting the foetus had already died before the women arrived at the KMH hospital.

Table 5. Adverse clinical outcomes after caesarean section and vaginal deliveries among tribal and non-tribal women.

| Caesarean section (N = 2250) | Vaginal deliveries (N = 17673) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tribal | Non-tribal | Unadjusted P-value | Tribal | Non-tribal | Unadjusted P-value | |

| Birth Asphyxia (no cry after Birth) n(%) | 4(0.3) | 6(0.6) | 0.267 | 56(0.5) | 20(0.4) | 0.541 |

| Birth weight <2500 grams n(%) | 572(44.0) | 283(29.8) | 0.000 | 5595(44.7) | 1713(33.2) | 0.000 |

| Still birth rate n(per 1000 live + still births) | 35(26.9) | 8(8.4) | 0.002 | 415(33.2) | 99(19.2) | 0.000 |

| Case fatality rate n(in hospital neonatal deaths per 1000 live births) | 17(13.1) | 13(13.7) | 0.901 | 263(19.0) | 84(13.7) | 0.010 |

Discussion

This is one of the few studies to compare the rates, indications and outcomes of caesarean section between tribal and non-tribal women in India. Studies in the past have shown lower caesarean section rate in India compare to other Asian countries [29–31]. Studies have also reported differences in caesarean section rates and other maternal health related indicators between tribal and non-tribal [1,4,32–33]. Higher caesarean rates have been reported among non-tribal women compared to tribal women in other studies in India [12,32–33]. Delaying the childbearing and improving the care-seeking behaviour among the tribal women in our study population might help to reduce the difference in the caesarean section rate [33–34]. Antenatal care visits during pregnancy may lead to the identification of complication and consequently higher caesarean section rates among women who have 3 or 4 ANC visits [34–35]. Age, education and parity of the women have been reported as important determinants of caesarean section in many studies as similar to our findings [19,30,34–35]. Our data could only explain around 40% of differences in the caesarean rates between tribal and non tribal. More research may be required for exploring the gap between tribal and non-tribal women. We also found higher risk of caesarean among women with previous caesarean as also depicted in many studies [7,36–37]. Household surveys also suggest availability, accessibility and affordability are one of the factors for less use of emergency obstetrics services [15,32,34,38]. In our study, the hospital provides round the clock, nearly free of cost, and good quality services, thereby facilitate availability and affordability. In addition, emergency ambulance service also functions at zero cost to the patient and makes the hospital easily accessible. This may also have contributed to the higher caesarean section rates among tribal women in our study compared to other studies.

Previous caesarean section, foetal distress and mal-presentation of the foetus (Breech and Transverse Lie) were the most common clinical indication for caesarean section in our study. Our results are relatively consistent with other studies in India and other countries [29,37]. Similar to our findings, the previous caesarean section, foetal distress and mal-presentation of the foetus (Breech and Transverse Lie) were reported as major indication of caesarean section in many studies [7,29,37]. Obstructed labour was also reported as an important indication in few studies [7]. However, obstructed labour was not a major indication of caesarean in our study. There are also variations between studies for reporting primary indications for caesarean section [27,39]. There is a need for universal clinical indications in which caesarean section can be performed [39]. We did not find any differences in neonatal outcomes comparing caesarean and vaginal deliveries. Studies have suggested non significant influences on neonatal morbidity and mortality in setting where the caesarean rates are very high (21–23). However, as suggested by WHO, caesarean section can be a life saving tool if performed in optimal condition and indications [10]. However, it might be noted that most of the women (70%) who had still birth were admitted with no foetal heart rate at the time of admission. The intra uterine foetal death before arriving to the hospital might have resulted in higher still birth rate in vaginal delivery. Considering the almost lack of data about caesarean section in tribal communities in India, it is critical to collect, analyze and review data about caesarean section rates segregated by caste [39].

There are a few lessons learned regarding how to develop tribal friendly health care facility for reducing the inequity of the health services in the tribal area. Some of the government sponsored policies that enabled the KMH to develop tribal friendly hospital, such as the grant-in-aid scheme and Chiranjivi Scheme could be explored for replicating in other tribal predominant states in India [40–41]. At the same time, it is important to take note of the KMH team’s efforts to prevent unnecessary caesarean section among tribal and non-tribal women by creating the culture of rational practice, and monitoring of caesarean section rates on the ongoing basis. The most common barrier for availing the caesarean section in tribal areas is the lack of qualified human resources such as obstetricians and anaesthesiologists [3,6,33–34]. Although the government is working towards improving human resources in the tribal area, more needs to be done to ensure every woman in need of life saving surgery of caesarean Section has access to it so that the Development Goals related to the maternal health can be achieved [40,42].

There are some limitations of this study. This study was done in the context of a tribal friendly hospital. The findings may not be generalized to other areas of India. Most of the women (90%) who had still birth were admitted with no foetal heart rate, which may cause higher still birth rate in vaginal delivery. It would have been useful to compare other outcomes of the caesarean section such as APGAR (Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity and Respiration) score along with the intra-operative and post-operative complications. Other mother related complication and delays in receiving services were also not available. The information was not available for the analysis. The study is based on maternal admissions; some women may have more than one delivery during the period of study.

Conclusion

It is one of the few studies which have compared indications and outcomes of caesarean section among tribal and non-tribal women in India. The caesarean rates were higher among non-tribal compared to tribal women. However, the adverse outcomes are similar among the tribal women compared to the non-tribal women who underwent the caesarean section. The previous caesarean section, maternal age, maternal education, parity and number of ANC visits are some of the important determinants of caesarean rates. The previous caesarean section among non-tribal and foetal distress in tribal was the most common indication of caesarean. Further research investigating and addressing the factors identified in this study are recommended.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Maya Hazra and other obstetricians who served at the Kasturba Maternity Hospital. We are also thankful to the SEWA Rural hospital staff for delivering excellent patient care in remote tribal areas of Gujarat. We thank the Government of Gujarat and India for schemes (Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana, Chiranjivi Yojana and Balsakha Yojana) and other donors for the functioning of the hospital. We are also thankful to Mudita Dave, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, for providing guidance in refining the English writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ANC

Antenatal Care

- CEmONC

Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care

- KMH

Kasturba Medical Hospital

- SEWA-Rural

Society for Education, Welfare and Action-Rural

- WHO

World Health Organization

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information file.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Anderson I, Robson B, Connolly M, Al-Yaman F, Bjertness E, King A, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (The Lancet—Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): a population study. The Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stephens C, Porter J, Nettleton C, Willis R. Disappearing, displaced, and undervalued: a call to action for Indigenous health worldwide. The lancet. 2006;367(9527): 2019–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paxton A, Bailey P, Lobis S, Fry D. Global patterns in availability of emergency obstetric care. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2006;93(3):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ronsmans C, Holtz S, Stanton C. Socioeconomic differentials in caesarean rates in developing countries: a retrospective analysis. The Lancet 2006;368:1516–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weil O, Fernandez H. Is safe motherhood an orphan initiative? The Lancet 1999;54: 940–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauer JA, Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Wojdyla D. Determinants of caesarean section rates in developed countries: supply, demand and opportunities for control. World Health Report 2010.

- 7.Chu K, Cortier H, Maldonado F, Mashant T, Ford N, Trelles M. Cesarean section rates and indications in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country study from Medecins sans Frontieres. PloS one. 2012;7(9):e44484 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alkire BC, Vincent JR, Burns CT, Metzler IS, Farmer PE, Meara JG. Obstructed labor and caesarean delivery: the cost and benefit of surgical intervention. PloS one. 2012;7(4):e34595 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Appropriate technology for birth. Lancet 1985;2: 436–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates: Geneva, Switzerland; 2015. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/cs-statement/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Registrar General of India. Census of India, Primary census abstract: a series. Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India 2011: New Delhi. http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/population_enumeration.html.

- 12.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. National Family Health Survey-4 (NFHS-4), India-Factsheet. http://rchiips.org/NFHS/pdf/NFHS4/India.pdf

- 13.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International. 2007. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005–06: India: Volume I. Mumbai.

- 14.Briand V, Dumont A, Abrahamowicz M, Traore M, Watier L, Fournier P. Individual and institutional determinants of caesarean section in referral hospitals in Senegal and Mali: a cross-sectional epidemiological survey. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2012;12(1): 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vora KS, Koblinsky SA, Koblinsky MA. Predictors of maternal health services utilization by poor, rural women: a comparative study in Indian States of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2015;33(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma B, Giri G, Christensson K, Ramani KV, Johansson E. The transition of childbirth practices among tribal women in Gujarat, India-a grounded theory approach. BMC international health and human rights. 2013;13(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh S, James KS. Levels and Trends in Caesarean Births: Cause for Concern?. Economic and political weekly. 2010. January 30:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavallaro FL, Cresswell JA, França GV, Victora CG, Barros AJ, Ronsmans C. Trends in caesarean delivery by country and wealth quintile: cross-sectional surveys in southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91(12):914–22D. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.117598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mishra U.S. and Ramanathan M., 2002. Delivery-related complications and determinants of caesarean section rates in India. Health Policy and Planning, 17(1), pp.90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun PM, Wilburn W, Raynor BD, Jamieson D. Sickle cell disease in pregnancy: twenty years of experience at Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta, Georgia. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2001;184(6):1127–1130. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.115477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ye J, Zhang J, Mikolajczyk R, Torloni MR, Gülmezoglu AM, Betran AP. Association between rates of caesarean section and maternal and neonatal mortality in the 21st century: a worldwide population-based ecological study with longitudinal data. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2016;123(5):745–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyu HH, Shannon HS, Georgiades K, Boyle MH. Caesarean delivery and neonatal mortality rates in 46 low-and middle-income countries: a propensity-score matching and meta-analysis of Demographic and Health Survey data. International journal of epidemiology. 2013: dyt081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Althabe F, Sosa C, Belizán JM, Gibbons L, Jacquerioz F, Bergel E. Cesarean section rates and maternal and neonatal mortality in low-, medium-, and high-income countries: an ecological study. Birth. 2006;33(4):270–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2006.00118.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pankaj Shah, Dhiren Modi, Gayatri Desai, Shobha Shah, Shrey Desai, Uday Gajiwala. Equity in utilization of hospital and maternal care services: Trend analysis at SEWA Rural, India. Inequity in maternal & child health 2016: 112–121. Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar. http://sewarural.org/sewa/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Equity-in-Utilization-of-Hospital-and-Maternal-Care-Services.pdf

- 25.Hakim R. Vasava identity in transition: Some theoretical issues. Economic and Political Weekly. 1996:31(24): 1492–1499. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Government of India, Ministry of Tribal Affairs. Schedules Tribes definitions. http://tribal.nic.in/Content/DefinitionpRrofiles.aspx.

- 27.Fairlie RW. An extension of the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition technique to logit and probit models. Journal of economic and social measurement. 2005;30(4):305–316. [Google Scholar]

- 28.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12 College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Festin MR, Laopaiboon M, Pattanittum P, Ewens MR, Henderson-Smart DJ, Crowther CA. Caesarean section in four South East Asian countries: reasons for, rates, associated care practices and health outcomes. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2009;9(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neuman M, Alcock G, Azad K, Kuddus A, Osrin D, More NS, Nair N, Tripathy P, Sikorski C, Saville N, Sen A. Prevalence and determinants of caesarean section in private and public health facilities in underserved South Asian communities: cross-sectional analysis of data from Bangladesh, India and Nepal. BMJ open. 2014;4(12):e005982 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The Increasing Trend in Caesarean Section Rates: Global, Regional and National Estimates: 1990–2014. PloS one. 2016;11(2):e0148343 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navaneetham K, Dharmalingam A. Utilization of maternal health care services in Southern India. Social science & medicine. 2002;55(10):1849–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jat TR, Ng N, San Sebastian M. Factors affecting the use of maternal health services in Madhya Pradesh state of India: a multilevel analysis. International journal for equity in health. 2011;10(1):59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biswas AB, Das DK, Misra R, Roy RN, Ghosh D, Mitra K. Availability and use of emergency obstetric care services in four districts of West Bengal, India. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2005:266–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahabuddin AS, Delvaux T, Utz B, Bardají A, De Brouwere V. Determinants and trends in health facility-based deliveries and caesarean sections among married adolescent girls in Bangladesh. BMJ open. 2016;6(9):e012424 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Getahun D, Oyelese Y, Salihu HM, Ananth CV. Previous cesarean delivery and risks of placenta previa and placental abruption. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006. April 1;107(4):771–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aminu M, Utz B, Halim A, Van Den Broek N. Reasons for performing a caesarean section in public hospitals in rural Bangladesh. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014;14(1):130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khanal V, Karkee R, Lee AH, Binns CW. Adverse obstetric symptoms and rural—urban difference in cesarean delivery in Rupandehi district, Western Nepal: a cohort study. Reproductive health. 2016;13(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torloni MR, Betran AP, Souza JP, Widmer M, Allen T, Gulmezoglu M, Merialdi M. Classifications for cesarean section: a systematic review. PloS one. 2011;6(1):e14566 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Randive B, Diwan V, De Costa A. India’s Conditional Cash Transfer Programme (the JSY) to promote institutional birth: Is there an association between institutional birth proportion and maternal mortality?. PloS one. 2013;8(6):e67452 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhat R, Mavalankar DV, Singh PV, Singh N. Maternal healthcare financing: Gujarat’s Chiranjeevi Scheme and its beneficiaries. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2009:249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Starrs AM. Safe motherhood initiative: 20 years and counting. The Lancet. 2006;368(9542):1130–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information file.