Abstract

MUC5AC is a secretory mucin aberrantly expressed in various cancers. In lung cancer, MUC5AC is overexpressed in both primary and metastatic lesions; however, its functional role is not well understood. The present study was aimed at evaluating mechanistic role of MUC5AC on metastasis of lung cancer cells. Clinically, the overexpression of MUC5AC was observed in lung cancer patient tissues and was associated with poor survival. In addition, the overexpression of Muc5ac was also observed in genetically engineered mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues (KrasG12D; Trp53R172H/+; AdCre) in comparison with normal lung tissues. Our functional studies showed that MUC5AC knockdown resulted in significantly decreased migration in two lung cancer cell lines (A549 and H1437) as compared with scramble cells. Expression of integrins (α5, β1, β3, β4 and β5) was decreased in MUC5AC knockdown cells. As both integrins and MUC5AC have a von Willebrand factor domain, we assessed for possible interaction of MUC5AC and integrins in lung cancer cells. MUC5AC strongly interacted only with integrin β4. The co-localization of MUC5AC and integrin β4 was observed both in A549 lung cancer cells as well as genetically engineered mouse adenocarcinoma tissues. Activated integrins recruit focal adhesion kinase (FAK) that mediates metastatic downstream signaling pathways. Phosphorylation of FAK (Y397) was decreased in MUC5AC knockdown cells. MUC5AC/integrin β4/FAK-mediated lung cancer cell migration was confirmed through experiments utilizing a phosphorylation (Y397)-specific FAK inhibitor. In conclusion, overexpression of MUC5AC is a poor prognostic marker in lung cancer. MUC5AC interacts with integrin β4 that mediates phosphorylation of FAK at Y397 leading to lung cancer cell migration.

INRODUCTION

Mucins contribute viscous properties to the lung and help trap-inhaled microbes and particulates. Aberrant expression and accumulation of mucins has been associated with lung cancer,1 inflammatory conditions2 and other chronic diseases.3–5 Mucins interact with various molecules and affect cell–cell interaction during cancer progression and metastasis.6–8 MUC5AC is a high molecular weight secretory polymeric mucin, synthesized as a glycoprotein in a selective and cell-specific manner.5,9 Multiple cysteine-rich domains in both N- and C-terminal regions of MUC5AC are responsible for its disulfide-mediated polymerization, which is critical for gel-forming properties.10 MUC5AC is expressed in the trachea and bronchi, but not in the bronchioles and smaller alveolar epithelial cells.11 It is also observed in the goblet cells of the surface epithelium and in the glandular ducts.11

MUC5AC expression has been shown to increase significantly during the progression from atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH) in the lung to adenocarcinoma.12 Alterations in the MUC5AC expression have been associated with dedifferentiation of bronchial epithelium.13 Yu et al.14 reported an increased expression of MUC5AC in smoking-associated lung cancers compared with non-smokers lung cancers patients.

Epidermal growth factor family and mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades regulate MUC5AC expression.11 Treatment of H292 lung cancer cells with growth factors such as epidermal growth factor and TNF-α resulted in increased expression of MUC5AC.11 Epidermal growth factor-mediated EGFR activation upregulates MUC5AC there by activating Ras/Raf pathway, which in turn leads to cancer cell proliferation. Overproduction of MUC5AC is associated with lung cancer progression and appears to be a marker of poor prognosis.15 Although overexpression of many mucins seems to have a significant role in chemoresistance, the effect of MUC5AC expression has not been studied.16–18 Similarly, the precise biological role and mechanism of action of MUC5AC in lung carcinogenesis is poorly understood.

Integrins belong to the family of cell adhesion receptors and have been implicated in cancer cell migration and invasion.19 Integrin signaling is strongly associated with extracellular matrix proteins during metastasis.20 In addition, integrins appear to be specifically associated with growth factors and oncogenes for tumor progression.19,21,22 MUC5AC induces migration of pancreatic cancer cells by enhancing the integrins expression.23 However, functional significance and co-existence of MUC5AC and integrins in lung cancer is not well elucidated. In the present study, we have evaluated the preclinical and clinical importance of MUC5AC in lung cancer and attempted to identify the molecular mechanism of MUC5AC-mediated lung cancer cell migration through integrin β4/focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling.

RESULTS

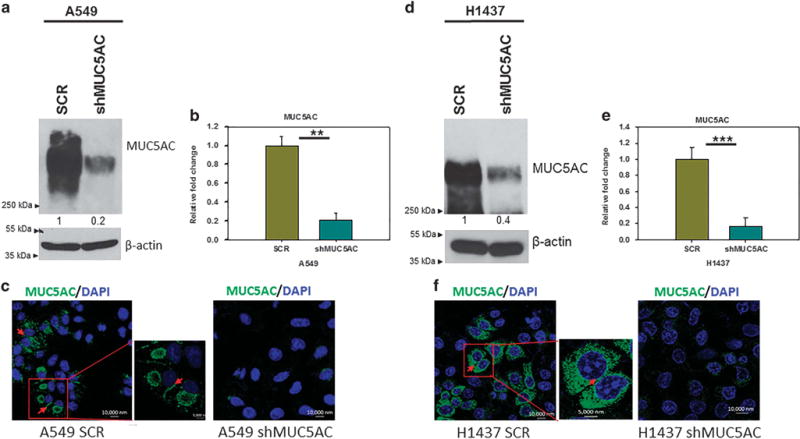

Stable knockdown of MUC5AC in lung cancer cells and its effect on cell growth

To explore the functional significance of MUC5AC in lung cancer, we performed stable knockdown of MUC5AC in two lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, A549 and H1437, which endogenously express high levels of MUC5AC. MUC5AC knockdown was validated using western blot and quantitative real-time PCR analysis. Both MUC5AC protein (Figures 1a and d) and mRNA (Figures 1b and e) expression were significantly reduced (A549 (P = 0.007) and H1437 (P = 0.001)) in MUC5AC knockdown cells as compared with respective scramble cells. MUC5AC knockdown was also confirmed by confocal studies (Figures 1c and f). MUC5AC knockdown cells had a significantly decreased growth rate (P = 0.01) compared with scramble cells (Supplementary Figure 1A). This appears to be due to decreased phosphorylation of Akt (Ser473) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) at T202/Y204 (Supplementary Figure 1B). These results suggest that overexpression of MUC5AC has an oncogenic role in lung cancer.

Figure 1.

Stable knockdown of MUC5AC in A549 and H1437 lung cancer cell lines. MUC5AC was stably knocked down in A549 and H1437 lung cancer cells, which endogenously express high level of MUC5AC as demonstrated by western blot (a, d). Similarly, transcript level of MUC5AC was significantly reduced in MUC5AC knockdown cells (A549 P = 0.007 and H1437 P = 0.001) as demonstrated by quantitative real-time PCR (b, e). Further, we have also performed confocal experiments to analyze the distribution of MUC5AC in lung cancer cells, in which MUC5AC is localized in both intra and inter cellular space of lung cancer cells (c, f). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

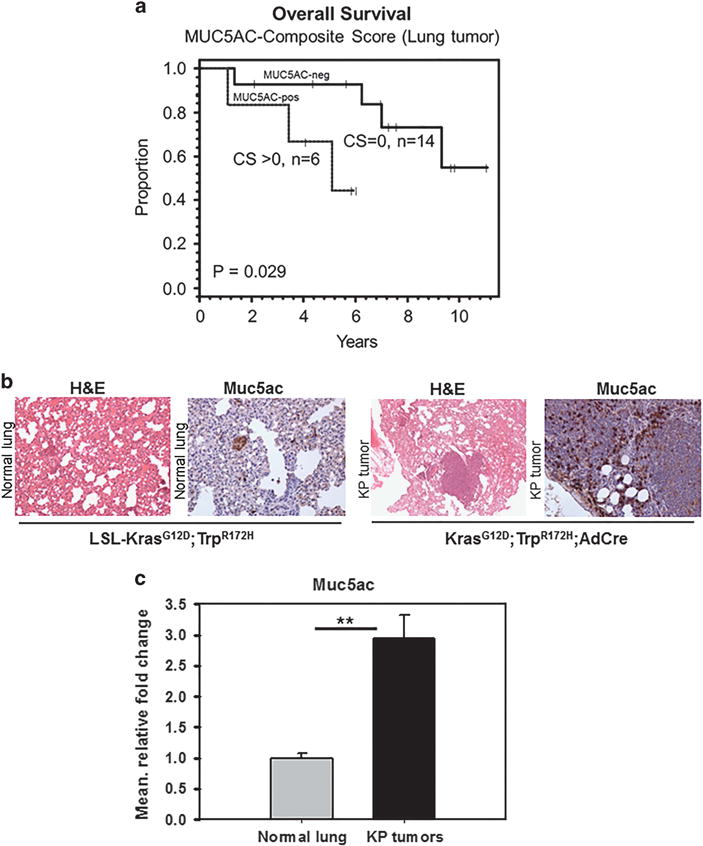

MUC5AC expression in human lung cancer tissues and its prognostic utility

We analyzed the MUC5AC expression in lung cancer patient tissues. Clinical information was available on 21 patients with a median age at diagnosis of 63 years (range: 44–79 years). Survival information was available on 20 patients. Patients without MUC5AC expression in their tumor cells had a longer survival compared with MUC5AC expressing tumors (P = 0.029). Five-year overall survival for MUC5AC-negative patients was 93% (95% confidence interval, 59–99%) compared with 67% in the MUC5AC expressing patients (95% confidence interval, 19–90%) (Figure 2a), indicating that MUC5AC is a prognostic marker for worse outcomes in lung cancer.

Figure 2.

Expression of MUC5AC in lung carcinoma tissues. To investigate the clinical significance of MUC5AC in lung cancer, its expression was analyzed in patient samples (#20). The results show that overexpression of MUC5AC (Composite score (CS)>0) is associated with poor prognosis of lung cancer patients (a). Muc5ac expression in mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues. Muc5ac is overexpressed in spontaneous KrasG12D;Trp53R172H/+;AdCre mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues. Muc5ac is overexpressed in mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues than normal lung tissues (b). In addition, quantitative real-time PCR analysis shows that Muc5ac transcript is significantly higher (P = 0.01) in lung adenocarcinoma as compared with normal lung tissues (c). **P<0.01.

Expression of Muc5ac in mouse lung adenocarcinoma using KPA (KrasG12D;Trp53R172H/+;AdCre) mouse model

We have developed a lung cancer model by nasal inhalation of AdCre for activation of KrasG12D;Trp53R172H/+ in the lung. We observed increased expression of Muc5ac in lung adenocarcinoma tissues (n = 4) from KrasG12D;Trp53R172H/+;AdCre mice compared with LSL- KrasG12D,Trp53R172H /+ littermate controls (histologically normal lung) (Figure 2b). The control mice lung tissues (n = 4) showed basal level of Muc5ac. Transcript level analysis of Muc5ac in mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues shows that Muc5ac is significantly increased in mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues (P = 0.01) compared with normal lung tissues (Figure 2c).

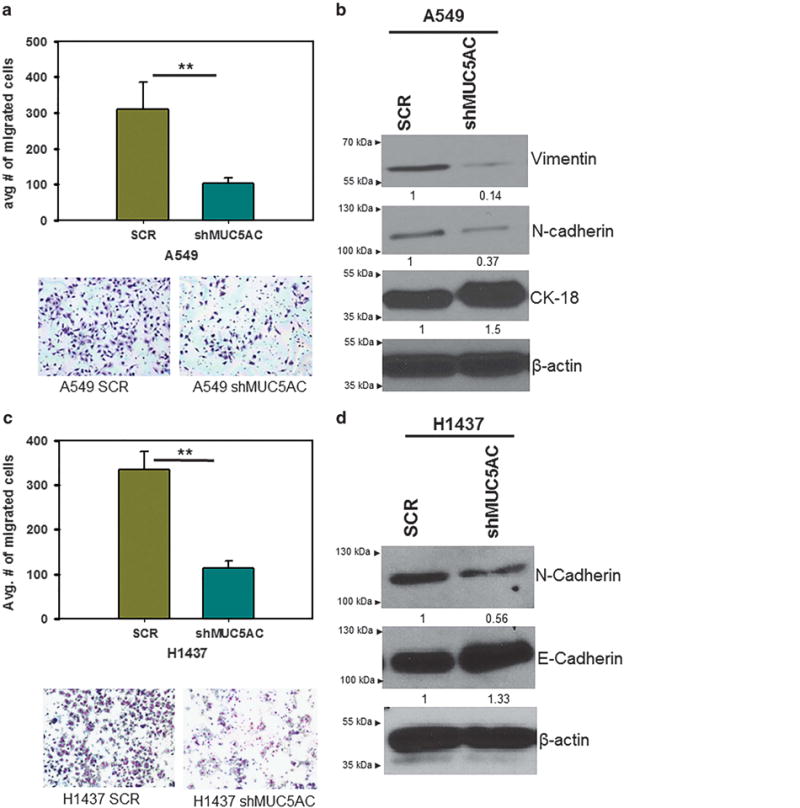

MUC5AC-induced lung cancer cell migration

As MUC5AC is associated with metastasis,14,24 we examined the role of MUC5AC on migration of lung cancer cells. Migration of MUC5AC knockdown cells was significantly reduced in comparison with scramble cells (A549 (P = 0.03) and H1437 (P = 0.02)) (Figures 3a and c). Further, the expression of mesenchymal markers N-cadherin and vimentin was decreased in MUC5AC knockdown cells (Figures 3b and d), and in contrast, epithelial markers CK-18 and E-cadherin were upregulated (Figures 3b and d) as compared with scramble cells. The endogenous level of E-cadherin protein expression is below the basal level or undetected in A549 cells,25 hence we analyzed another epithelial marker CK-18.

Figure 3.

Effect of MUC5AC on motile properties of lung cancer cells. Migration of MUC5AC knockdown cells was significantly reduced (A549, P = 0.03; H1437 P = 0.02) (a, c). Mesenchymal markers vimentin and N-cadherin were decreased in MUC5AC knockdown cells in comparison with scramble cells. In contrast, epithelial cell marker CK-18 and E-cadherin were increased in MUC5AC knockdown cells than scramble cells (b, d). **P<0.001.

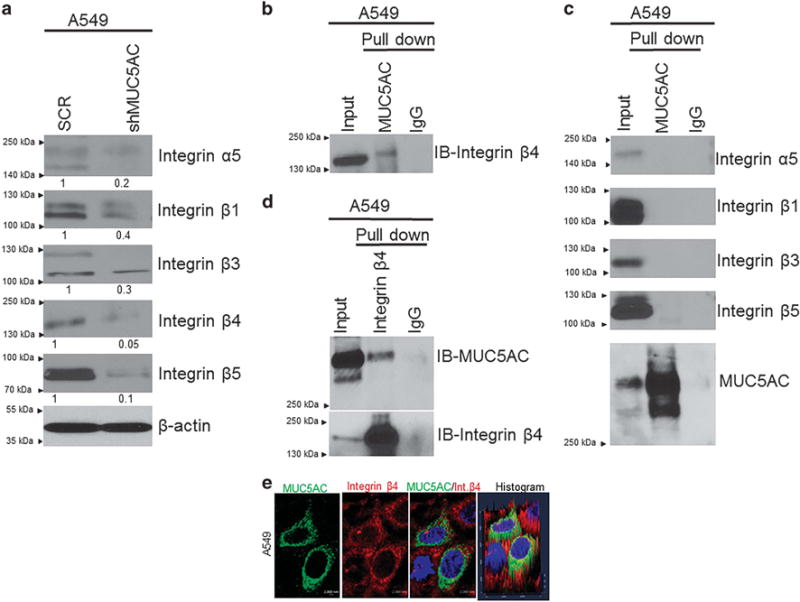

MUC5AC interacts with integrin β4 in lung cancer cells

Upon MUC5AC knockdown, expression of integrins such as integrin α5, β1, β3, β4 and β5 was decreased (Figure 4a). Integrins mediate inter- and intracellular signaling by heterodimerization.19 Integrins promote tumor cell migration and invasion by binding with extracellular matrix, which provides a suitable environment for tumor cell motility and invasion.26,27 These results suggest that integrins may also have an important role in lung cancer cell migration.

Figure 4.

Interaction of MUC5AC and integrin β4 in lung cancer cells. Upon knocking down of MUC5AC, the expression of integrin α5, β1, β3, β4 and β5 were decreased as compared with scramble cells (a). Co-immunoprecipitation assay results show that MUC5AC strongly interacts with integrin β4 (b), but not with other integrins (α5, β1, β3 and β5) (c). Similarly, we have also performed reciprocal co-immunoprecipitation assay to pull down integrin β4 and probed with MUC5AC (d). MUC5AC strongly interacts with integrin β4 in lung cancer cells. Co-localization of MUC5AC and integrin β4 was also observed in A549 cells as indicated by confocal analysis (e).

Integrins also associate with growth factors and oncogenes during cancer cell migration and invasion.21,22,28,29 Both integrins and MUC5AC share the von Willebrand factor domain,30,31 which is required for dimerization or oligomerization. We hypothesized that the presence of von Willebrand factor domains in both integrins and MUC5AC may lead to their interaction with each other. To assess interaction between these two proteins, we pulled down MUC5AC and probed with various integrins (α5, β1, β3, β4 and β5). MUC5AC specifically interacted with integrin β4 as indicated by immunoprecipitation assay (Figure 4b), whereas there was no interaction observed with other integrins (Figure 4c). In addition, we also pulled down integrin β4 and probed with MUC5AC, and observed that MUC5AC and integrin β4 interact each other in lung cancer cells (Figure 4d). Similarly, we have also confirmed the co-localization of MUC5AC and integrin β4 in A549 cells by confocal analysis (Figure 4e). Thus, MUC5AC associates with integrin β4 in lung cancer cells.

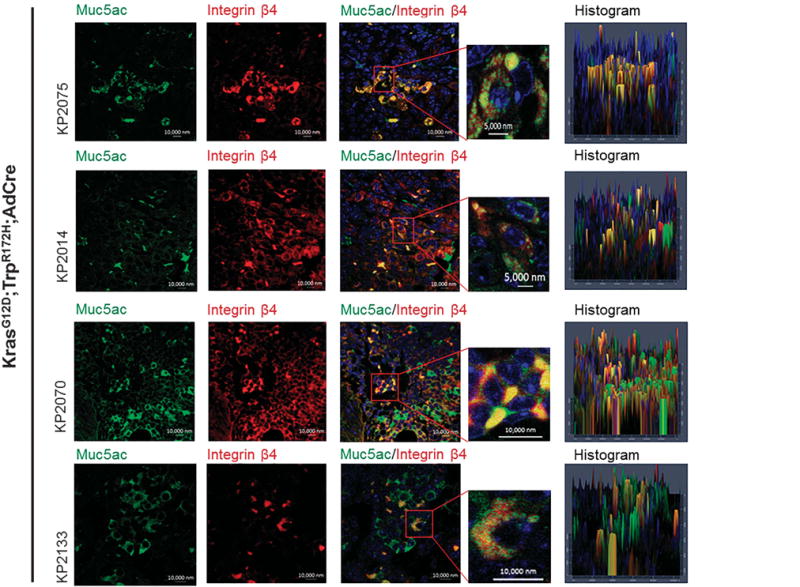

Co-localization of Muc5ac and integrin β4 in genetically engineered mouse adenocarcinoma tissues

To validate the MUC5AC/integrin β4 association in mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues, we examined the association of Muc5ac and integrin β4 in the mouse lung adenocarcinoma (KrasG12D; Trp53R172H/+;AdCre). Muc5ac was strongly co-localized with integrin β4 in various mouse adenocarcinoma tissues, which indicates that Muc5ac/integrin β4 association may be required for lung cancer initiation, progression and metastasis (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Co-localization of Muc5ac and integrin β4 in mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues. Using AdenoCre-mediated lung adenocarcinoma tissues (KrasG12D, Trp53R172H/+), we analyzed the co-existence of MUC5AC and integrin β4 by immunofluorescence studies. Muc5ac (green) is strongly co-localized with integrin β4 (red) in mouse lung adenocarcinoma tissues.

Molecular mechanisms of MUC5AC-mediated lung cancer cell migration

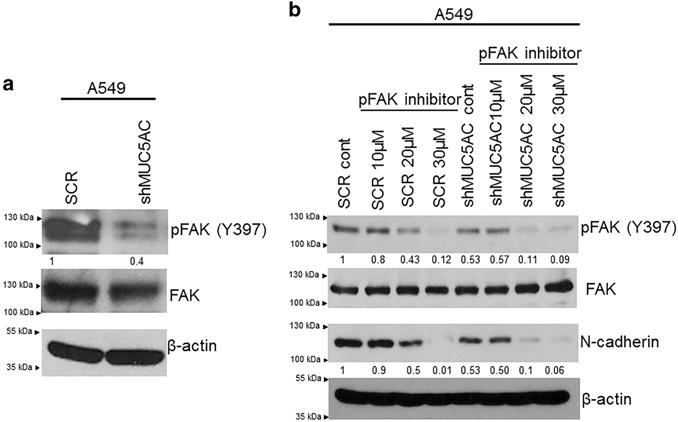

FAK is a key downstream signaling molecule triggered by integrin activation.32–34 Activation of integrins leads to recruitment of FAK, which is responsible for migration and metastasis of cancer cells.27,35 Upon MUC5AC knockdown, phosphorylation of FAK (Y397) was decreased (Figure 6a and supplementary Figure 2), suggesting that MUC5AC induces lung cancer cell migration, may be in part, through integrin β4-FAK pathway.

Figure 6.

MUC5AC/FAK-mediated motility of lung cancer cells and effect of FAK inhibition on motility. Following MUC5AC knockdown, phosphorylation of FAK (Y397) was decreased as compared with scramble cells (a). The total FAK was unchanged in both scramble and MUC5AC knockdown cells. Using FAK (Y397)-specific and direct inhibitor, we have confirmed the phosphorylation of FAK (Y397) is important for lung cancer cell migration. Phosphorylation of FAK Y397 was greatly inhibited at 20 μM but total of FAK was unchanged. Expression of N-cadherin was decreased upon treatment with FAK inhibitor as compared with untreated cells (b).

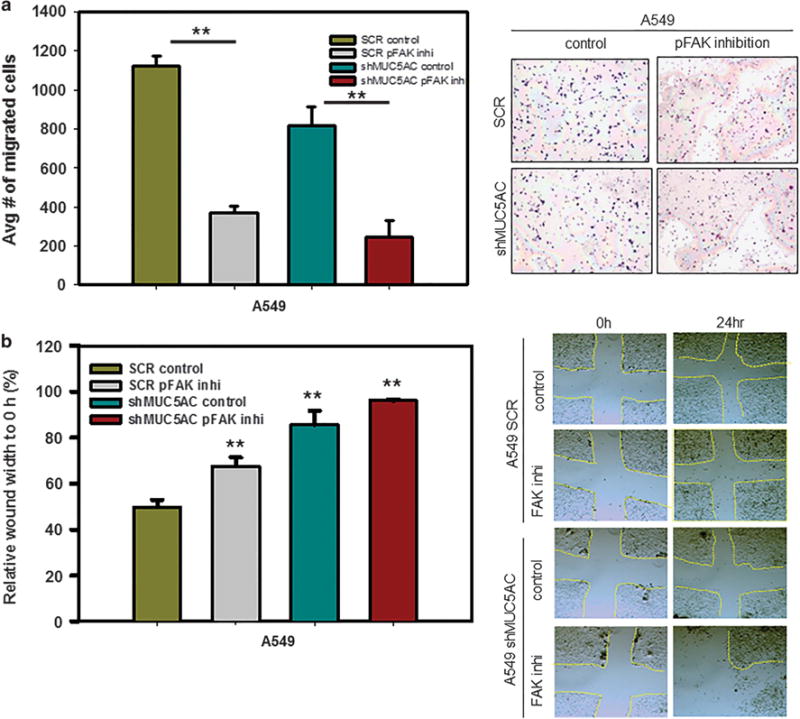

Inhibition of FAK phosphorylation attenuates lung cancer cell migration

As demonstrated above, MUC5AC promotes cell migration through the FAK pathway. To evaluate the role of phosphorylation of FAK in this process, a phosphorylation-specific inhibitor for FAK (FAK inhibitor 14, phosphorylation-specific inhibitor) was used.36 Following exposure to the FAK inhibitor (20 μM), phosphorylation of FAK (Y397) was decreased in A549 cells (Figure 6b). On treatment with FAK inhibitor, we observed the downregulation of N-cadherin (Figure 6b). We also observed that migration of lung cancer cells was significantly reduced in FAK inhibitor-treated cells as compared with their corresponding untreated controls (Figure 7a). Similarly, wound-healing capacity was significantly reduced following treatment with a FAK inhibitor as compared with untreated cells (Figure 7b). These results confirm the importance of FAK phosphorylation in mediating MUC5AC-induced cell migration.

Figure 7.

Effect of FAK inhibitor on migration of lung cancer cells. Migration of lung cancer cells was significantly decreased in scramble (P = 0.002) and MUC5AC knockdown cells (P = 0.003) following exposure to pFAK inhibitor (20 μM) as compared with untreated cells (a). In a wound-healing assay, following exposure to a pFAK inhibitor (20 μM), there was decreased migration of lung cancer cells as compared with untreated cells (b). **P<0.01.

MUC5AC confers cisplatin resistance in lung cancer cells

Overexpression of mucins in cancer cells confers chemoresistance that leads to cancer cell survival and tumor relapse.16,37–39 We performed 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay with MUC5AC knockdown and scramble cells after exposure to various concentrations of cisplatin. MUC5AC knockdown cells were more sensitive to cisplatin as compared with scramble cells, which suggests that endogenous expression of MUC5AC confers cisplatin resistance (Supplementary Figure 3A). Further, cisplatin treated MUC5AC knockdown cells have less viability than cisplatin treated scramble cells (Supplementary Figure 3B).

DISCUSSION

Overexpression of mucins is associated with proliferation and metastasis of lung cancer cells.40–42 MUC5AC is a secretory glycoprotein, which is normally expressed in the lung; but its expression is altered in lung cancer.4,5,43–45 In the present study, we elucidate the role of MUC5AC in lung cancer cell growth and metastasis. Following MUC5AC knockdown in two lung adenocarcinoma cell lines, we observed significant reduction of growth. In addition, decreased phosphorylation of AKT (Ser473) and ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) was observed in MUC5AC knockdown cells as compared with scramble cells, suggesting that MUC5AC has an oncogenic role in lung cancer. Further, we analyzed the clinical significance of MUC5AC in lung cancer, and observed that overexpression of MUC5AC was associated with poor outcomes. Similarly, Muc5ac is overexpressed in mice lung adenocarcinoma tissues (KrasG12D;Trp53R172H/+;AdCre), suggesting that Muc5ac may have a significant role in lung pathogenesis.

MUC5AC is found to be overexpressed in both primary and metastatic lesions in multiple cancers.14,46,47 In this study, we observed that MUC5AC knockdown leads to significantly less migratory capacity. Mesenchymal cell markers N-cadherin and vimentin were decreased in MUC5AC knockdown cells, in contrast, epithelial marker CK-18 and E-cadherin were increased. These result suggests that MUC5AC is involved in the migration of lung cancer cells.

Interestingly, silencing of MUC5AC resulted in decreased expression of integrins α5, β1, β3, β4 and β5, suggesting that MUC5AC/integrin signaling may be involved in the migration of lung cancer cells. Previous studies have well demonstrated that integrins induces the metastatic signaling through heterodimerization process through α- and β- subunit.26,48 In addition, integrins also activate metastatic signaling by binding with various oncogenes and growth factors.21,22,28 Both integrins and MUC5AC have a von Willebrand factor domain, which is responsible for dimerization or oligomerization.30,31 This raises the possibility that von Willebrand factor domain of the two molecules may interact with each other in lung cancer cells. We performed reciprocal immunoprecipitation assay and observed an interaction between MUC5AC and integrin β4. Other integrins did not show any interactions with MUC5AC in lung cancer cells. Further co-localization of MUC5AC and integrin β4 was observed both in lung cancer cell lines and mice lung adenocarcinoma tissues. These results strongly indicate that MUC5AC/integrin β4 interaction may be required for lung cancer pathogenesis. To support our findings, previous studies have demonstrated that integrin β4 is overexpressed in non-small cell lung cancer and associated with lung cancer pathogenesis.22,49

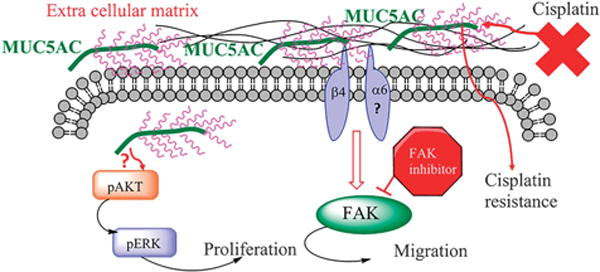

Our next goal was to analyze the MUC5AC/integrin-dependent metastatic downstream signaling alteration in lung cancer cells. Previous studies indicated that integrins activate FAK downstream signaling during migration of cancer cells.35,50 We observed that phosphorylation of FAK at Y397 was reduced in MUC5AC knockdown cells, which suggests that MUC5AC regulates integrin-FAK-mediated lung cancer cell migration. Previous studies suggest that FAK-mediated signal transduction for cancer cell migration may be triggered by integrins.35,50 In the present study, inhibition of phosphorylation of FAK resulted in decreased migration in both MUC5AC knockdown and scramble cells. In addition, MUC5AC knockdown cells had lesser migratory capacity in comparison with scramble treated with phospho FAK inhibitor, which suggests that overexpression of MUC5AC may induce integrin β4 mediated lung cancer cell migration through FAK activation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation for MUC5AC-mediated lung cancer cell growth, migration and cisplatin resistance. MUC5AC regulates the expression of integrin β4 in lung cancer. MUC5AC interacts with integrin β4, which is required for lung cancer cell migration. This interaction activates FAK-mediated downstream signaling that results in cell migration. Inhibition of FAK resulted in decreased motility and wound healing, suggesting that FAK phosphorylation is required for MUC5AC-mediated lung cancer cell migration. In addition, overexpression of MUC5AC confers cisplatin resistance in lung cancer cells.

Overexpression of mucins has been associated with chemoresistance.16,37,38 However, the effects of MUC5AC on chemosensitivity have not been explored so far. A previous study demonstrated that expression of MUC5AC was associated with resistance to methotrexate, but sensitivity to 5-FU.39 Platinum agents including cisplatin are routinely used in the treatment of lung cancer.51 We found that MUC5AC knockdown cells were more sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of cisplatin, which suggests that MUC5AC is involved in chemoresistance of lung cancer cells.

CONCLUSIONS

MUC5AC is overexpressed in human and mouse lung adenocarcinoma compared with normal lung tissue. Silencing of MUC5AC is involved in decreased proliferation and metastatic properties of lung cancer cells. Furthermore, MUC5AC interacts with integrin β4 and enhance the migration of lung cancer cells through FAK signaling. Finally, MUC5AC expression leads to cisplatin resistance. Overall, MUC5AC is an important molecule in the pathogenesis of lung cancer (Figure 8).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient characteristics

Clinical information was collected on patients with non-small cell lung cancer. The human lung tissue microarrays were obtained through the Chicago Tissue Procurement Shared Resource facility for this study. All the tissues were obtained after getting consent from all the tissue donors prior to their death, as per the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board-approved protocol.

Scoring and statistical analysis

Immunohistochemistry was performed on the samples collected from these patients using anti-MUC5AC (mouse, 1:400, Abcam Cat #3649, Cambridge, MA, USA) mouse monoclonal antibody. Each sample was given a composite score based on intensity and extent of tissue staining. Intensity was graded on a four point scale: − (0), + (1), ++ (2) and +++ (3). Extent of staining was graded as: 1 (0–24%), 2 (25–49%), 3 (50–74%) and 4 (75–100%). The composite score was obtained by multiplying the two values. A generalized linear mixed model was used to test for difference in maximum composite score. Pairwise comparisons on the same patient were adjusted for multiple comparisons with Tukey’s method. Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate overall survival distributions, and the log rank test was used to compare survival distributions.

Generation of spontaneous lung cancer mouse model

Genetically engineered mouse models for lung cancer (KP) were developed by the Tuveson laboratory52 by crossing LSL-KrasG12D (B6.129-Krastm4Tyj (01XJ6)) mice with Trp53R172H to generate KrasG12D; Trp53R172H/+ (KP) as described previously.53,54 The F1 progeny were genotyped for KrasG12D and Trp53R172H/+ genes using specific primers for Kras and Trp53 genes by PCR. Animals that were positive for both KrasG12D and Trp53R172H/+ were randomized into two groups, one group infected with AdCre-luciferase retroviral vector intra nasally (University of Iowa, Gene and vector core, IA, USA) and other with vehicle control. Four weeks post infection, the animals were injected with luciferin intra-peritoneally to monitor the tumor growth (non-invasive in vivo live imaging using IVIS system). Mice were fed with food and water ad libitum and subjected to 12 h light/dark cycle. The mice studies were performed in accordance with the US Public Health Service ‘Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’ under an approved protocol by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Cell culture and transfection

A549 and H1437 non-small cell lung cancer cell lines were used in these experiments. A549 is a human alveolar adenocarcinoma cell line derived from the primary lung cancer tissue of a Caucasian male, whereas H1437 is an adenocarcinoma cell line derived from pleural effusions of lung cancer cells metastasized to pleural space of a Caucasian male patient. A549 and H1437 possess similarity in morphology, epithelial type. The most common mutations observed in H1437 are CDKN2A and TP53, whereas A549 harbors a KRAS mutation.

These cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics.25 The cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Endogenously expressed MUC5AC was knocked down using a MUC5AC small hairpin RNA construct (pSUPER-Retro- shMUC5AC) by a stable transfection method. Using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), MUC5AC small hairpin RNA and scramble vector were transfected into phoenix cells, a packaging cell line that produces high-titer retrovirus in culture.

The cells were then seeded in 24-well plates at a seeding density of 2 × 104 cells per well and grown to 40–70% confluency in serum-free growth medium. Culture supernatant medium from transfected phoenix cells was filtered 48 h post transfection, and the viral supernatant was used to infect the cultures of sub confluent A549 and H1437 cells with the addition of 4 μg/ml polybrene. Clones stably transduced with MUC5AC small hairpin RNA construct were selected, maintained using the antibiotic puromycin (4 μg/ml) in 10% RPMI medium and were further expanded to confluent levels to obtain stably transfected cells.55

Immunoblot analysis

For immunoblot analysis, the cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) containing protease inhibitors (1 mM phenyl–methyl sulphonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml leupeptin). Cell lysates were centrifuged at 10 000 rpm for 30 min to remove debris, and proteins were quantified using the Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Total protein (20 μg per well) was fractionated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. For MUC5AC; 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate-agarose gel was used for separation owing to its high molecular weight. Fractionated proteins were electrophoretically transferred on to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After transfer, the membranes were washed with PBST (phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 0.1% Tween 20) and blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in PBS for at least 1 h. The blots were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the following primary antibodies with respective dilutions: MUC5AC (mouse, 1:1000, Abcam Cat #3649), pERK (rabbit, 1:1000, Cell signaling technology #9101, Danvers, MA, USA), ERK (mouse 1:2000, Cell signaling technology #9102), pFAK (Y397) (rabbit, 1:2000, Cell signaling technology #3283), E-cadherin (mouse, 1:1500) and N-cadherin (mouse, 1:1500) antibodies were kind gift from Dr Keith R Johnson, UNMC, Omaha, NE, USA CK-18 (mouse, 1:1500, Abcam #668), Vimentin (mouse, 1:1500), pAkt (rabbit, 1:1500, Cell signaling technology #9271), Akt (rabbit, 1:2000, Cell signaling technology #9272), integrin α5, β1, β3, β4, β5 (rabbit, 1:2000, Cell signaling technology #4749) and anti-β-actin (mouse 1:5000, Sigma #A1978, St Louis, MO, USA) (diluted in 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS). The membranes were then washed (3 × 10 min) in PBST, probed with the appropriate secondary antibodies at 1:2000 dilution, incubated for an hour at room temperature and subsequently washed with PBST (3 × 10 min). The signals were detected with the ECL chemiluminescence kit (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA).

Immunoprecipitation analysis

MUC5AC (45M1, Abcam Cat # 3649) and integrin β4 (Abcam Cat #133682) antibodies were incubated overnight with A549 cell lysates (500 μg) in a 750 μl total volume. Protein A+G-Sepharose beads (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St Louis, MO, USA) were added to the lysate-antibody mix and incubated on a rotating platform for 4 h at 4 °C and then washed four times with immunoprecipitation assay buffer. The immunoprecipitates and input were electrophoretically resolved on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (8%). Resolved proteins were transferred onto the polyvinyldifluoride membrane. The membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS for at least 1 h and then incubated with primary antibodies (anti-integrins (α5, β1, β3, β4 and β5)). The immunoblots were washed five times (5 × 10 min) with PBST, incubated for 1 h with respective secondary antibodies, washed five times (5 × 10 min) with PBST, reacted with enhanced chemiluminescence ECL reagent (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) and exposed to X-ray film to detect the signal.

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

MUC5AC knockdown A549 and H1437 and scramble cells (0.4 × 106 cells per well) were grown on sterilized cover slips for 30 h. Cells were washed with Hanks buffer containing 0.1 M 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethane-sulfonic acid (2 × 5 min) and fixed in ice-cold methanol at − 20 °C for two min. Similarly, co-immunofluorescence analysis were performed with paraffin embedded mouse lung cancer tissues as described previously.55 The cells were then blocked with 10% goat serum (Jackson Immunoresearch Labs, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) for at least 30 min. After blocking, a quick wash was performed using PBS and cells were incubated with antibodies for MUC5AC (mouse 1:1000) and integrin β4 (rabbit, 1:750) for 60 min at room temperature. Then cells were washed (4 × 5 min) with PBS and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse and rhodamine conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch Labs Inc.) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Cells were washed again (5 × 5 min) and mounted on glass slides in anti-fade Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole was used for nuclear staining. Laser confocal microscopy was performed using an LSM 510 microscope (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Germany).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated and the cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription. The primers were designed using Primer 3 software tool and following are the primers used for the study. MUC5AC: Real-time PCR was performed on Roche 480 Real-Time PCR System (Indianapolis, IN, USA). They were performed in triplicates and the template controls were run for each assay under the same conditions. PCR was then performed in 10 μl reaction volume containing 5 μl of SBYR green Master Mix, 3.2 μl of autoclaved nuclease-free water, 1 μl of diluted RT product (1:10) and 0.4 ml each of forward and reverse primers (5 pmol). The cycling conditions comprized of 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 sec and 58 °C for 1 min. Gene expression levels were normalized to the level of β-actin expression.

Cell motility assay

Motility assay was performed by using a chamber containing monolayer-coated polyethylene teraphthalate membrane (six-well insert, pore size of 8 μm; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Both scramble and MUC5AC knockdown cells of A549 (2 × 106 cells per well) and H1437 (1.5 × 106 cells per well) were seeded in six-well plates. After 24 h incubation period, the migrated cells that had reached the lower chamber were stained with a Diff-Quick stain set and counted in different fields. The average number of migrated cells per representative field was calculated. Similarly, for FAK inhibitor treatment studies, cells were seeded along with FAK inhibitor (FAK inhibitor 14, Cayman chemical, CAS4506-66-5), which direct inhibitor and specific for FAK (Y397)36 and incubated for 24 h and migrated cells were calculated.

Wound-healing assay

For wound-healing assays, 4 × 106 of A549 Scr and shMUC5AC cells were seeded in 6-well plates with 10% RPMI 1640 media. After 24 h, cells were treated with 20 μM of FAK inhibitor. A scratch was made on the bottom of each well using a P200 pipette tip. Photographs of the scratch were taken at 0 h and 24 h. The pictures were then analyzed to quantify the change in size of the scratches as the cells migrated into the space in response to FAK inhibitor.

Phosphorylation-specific FAK inhibition

For FAK inhibition, A549 Scr and shMUC5AC cells were seeded in 100mm petri dish with RPMI media. After seeding, cells were treated with phosphorylation-specific FAK inhibitor (20 μM) and for control 0.01% DMSO was used. After treating with the FAK inhibitor, cell viability was calculated as described previously.56

MTT assay and cisplatin treatment in lung cancer cells

Cell viability was determined using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay as described previously.56 In brief, Scr-A549 and shMUC5AC cells were seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 8 × 103 cells per well in RPMI medium with 10% FBS. After 24 h, the culture media was aspirated and supplemented with fresh media containing different concentrations of cisplatin (20 μM, 25 μM, 30 μM, 35 μM, 40 μM and 45 μM). After 48 h, 10 μl of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (5 mg/ml in PBS) solution were added to each well (including control cells). Then cells were further incubated for 3 h and then the absorbance was read at 560 nm with a reference wavelength of 670 nm using microplate reader. Based on IC50, we chose 20 μM concentration of cisplatin for further experimental validation of FAK inhibition.

Data analysis

Statistical significance was evaluated with the student t-test using sigmaPlot 11.0 software. P-values <0.05 were considered to be significant. Densitometry analyses were performed using ImageJ software. All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable technical support from Mrs Kavita Mallya and Ms Lynette Smith. We also thank Janice A Tayor and James R Talaska, of the confocal laser scanning microscope core facility at UNMC, for their support. The work is partly supported by grants from the US Department of Veterans’ Affairs, UNMC Department of Internal Medicine Summer Undergraduate Research Program and Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA036727) and National Institutes of Health (P50 CA127297, U54 CA163120, RO1 CA183459, RO1 CA195586, K22 CA175260 and P20 GM103480).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Thai P, Loukoianov A, Wachi S, Wu R. Regulation of airway mucin gene expression. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:405–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans CM, Raclawska DS, Ttofali F, Liptzin DR, Fletcher AA, Harper DN, et al. The polymeric mucin Muc5ac is required for allergic airway hyperreactivity. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6281. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrianifahanana M, Moniaux N, Batra SK. Regulation of mucin expression: mechanistic aspects and implications for cancer and inflammatory diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1765:189–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans CM, Kim K, Tuvim MJ, Dickey BF. Mucus hypersecretion in asthma: causes and effects. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15:4–11. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32831da8d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roy MG, Rahmani M, Hernandez JR, Alexander SN, Ehre C, Ho SB, et al. Mucin production during prenatal and postnatal murine lung development. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:755–760. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0020OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corfield AP. Mucins: a biologically relevant glycan barrier in mucosal protection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850:236–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glavey SV, Huynh D, Reagan MR, Manier S, Moschetta M, Kawano Y, et al. The cancer glycome: carbohydrates as mediators of metastasis. Blood Rev. 2015;29:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakshmanan I, Ponnusamy MP, Macha MA, Haridas D, Majhi PD, Kaur S, et al. Mucins in lung cancer: diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic implications. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:19–27. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adsay NV, Merati K, Nassar H, Shia J, Sarkar F, Pierson CR, et al. Pathogenesis of colloid (pure mucinous) carcinoma of exocrine organs: Coupling of gel-forming mucin (MUC2) production with altered cell polarity and abnormal cell-stroma interaction may be the key factor in the morphogenesis and indolent behavior of colloid carcinoma in the breast and pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:571–578. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, McGuckin MA. Structure and function of the polymeric mucins in airways mucus. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:459–486. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrais M, Pigny P, Copin MC, Aubert JP, Van SI. Induction of MUC2 and MUC5AC mucins by factors of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family is mediated by EGF receptor/Ras/Raf/extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade and Sp1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32258–32267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awaya H, Takeshima Y, Yamasaki M, Inai K. Expression of MUC1, MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 in atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes, and mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma of the lung. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:644–653. doi: 10.1309/U4WG-E9EB-FJN6-CM8R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Ferrer A, Curull V, Barranco C, Garrido M, Lloreta J, Real FX, et al. Mucins as differentiation markers in bronchial epithelium. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma display similar expression patterns. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:22–29. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.1.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu CJ, Shih JY, Lee YC, Shun CT, Yuan A, Yang PC. Sialyl Lewis antigens: association with MUC5AC protein and correlation with post-operative recurrence of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2005;47:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishiumi N, Abe Y, Inoue Y, Hatanaka H, Inada K, Kijima H, et al. Use of 11p15 mucins as prognostic factors in small adenocarcinoma of the lung. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:5616–5619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonckheere N, Skrypek N, Van SI. Mucins and tumor resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1846:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mimeault M, Johansson SL, Senapati S, Momi N, Chakraborty S, Batra SK. MUC4 down-regulation reverses chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer stem/progenitor cells and their progenies. Cancer Lett. 2010;295:69–84. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trehoux S, Duchene B, Jonckheere N, Van SI. The MUC1 oncomucin regulates pancreatic cancer cell biological properties and chemoresistance. Implication of p42-44 MAPK, Akt, Bcl-2 and MMP13 pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;456:757–762. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hood JD, Cheresh DA. Role of integrins in cell invasion and migration. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nrc727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo W, Pylayeva Y, Pepe A, Yoshioka T, Muller WJ, Inghirami G, et al. Beta 4 integrin amplifies ErbB2 signaling to promote mammary tumorigenesis. Cell. 2006;126:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stewart RL, O’Connor KL. Clinical significance of the integrin alpha6beta4 in human malignancies. Lab Invest. 2015;95:976–986. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamazoe S, Tanaka H, Sawada T, Amano R, Yamada N, Ohira M, et al. RNA interference suppression of mucin 5AC (MUC5AC) reduces the adhesive and invasive capacity of human pancreatic cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:53. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanada Y, Yoshida K, Konishi K, Oeda M, Ohara M, Tsutani Y. Expression of gastric mucin MUC5AC and gastric transcription factor SOX2 in ampulla of vater adenocarcinoma: comparison between expression patterns and histologic subtypes. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majhi PD, Lakshmanan I, Ponnusamy MP, Jain M, Das S, Kaur S, et al. Pathobiological implications of MUC4 in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:398–407. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182829e06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo W, Giancotti FG. Integrin signalling during tumour progression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:816–826. doi: 10.1038/nrm1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitra SK, Schlaepfer DD. Integrin-regulated FAK-Src signaling in normal and cancer cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:516–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Connor KL, Chen M, Towers LN. Integrin alpha6beta4 cooperates with LPA signaling to stimulate Rac through AKAP-Lbc-mediated RhoA activation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;302:605–614. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00095.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eberwein P, Laird D, Schulz S, Reinhard T, Steinberg T, Tomakidi P. Modulation of focal adhesion constituents and their down-stream events by EGF: on the cross-talk of integrins and growth factor receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1853:2183–2198. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hollingsworth MA, Swanson BJ. Mucins in cancer: protection and control of the cell surface. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:45–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuckwell DS, Humphries MJ. A structure prediction for the ligand-binding region of the integrin beta subunit: evidence for the presence of a von Willebrand factor A domain. FEBS Lett. 1997;400:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schlaepfer DD, Hauck CR, Sieg DJ. Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1999;71:435–478. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sieg DJ, Hauck CR, Schlaepfer DD. Required role of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) for integrin-stimulated cell migration. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2677–2691. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.16.2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sieg DJ, Hauck CR, Ilic D, Klingbeil CK, Schaefer E, Damsky CH, et al. FAK integrates growth-factor and integrin signals to promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:249–256. doi: 10.1038/35010517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guan JL. Integrin signaling through FAK in the regulation of mammary stem cells and breast cancer. IUBMB Life. 2010;62:268–276. doi: 10.1002/iub.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golubovskaya VM, Nyberg C, Zheng M, Kweh F, Magis A, Ostrov D, et al. A small molecule inhibitor, 1,2,4,5-benzenetetraamine tetrahydrochloride, targeting the y397 site of focal adhesion kinase decreases tumor growth. J Med Chem. 2008;51:7405–7416. doi: 10.1021/jm800483v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bafna S, Kaur S, Momi N, Batra SK. Pancreatic cancer cells resistance to gemcitabine: the role of MUC4 mucin. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kharbanda A, Rajabi H, Jin C, Raina D, Kufe D. Oncogenic MUC1-C promotes tamoxifen resistance in human breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:714–723. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leteurtre E, Gouyer V, Rousseau K, Moreau O, Barbat A, Swallow D, et al. Differential mucin expression in colon carcinoma HT-29 clones with variable resistance to 5-fluorouracil and methotrexate. Biol Cell. 2004;96:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biolcel.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khodarev NN, Pitroda SP, Beckett MA, MacDermed DM, Huang L, Kufe DW, et al. MUC1-induced transcriptional programs associated with tumorigenesis predict outcome in breast and lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2833–2837. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kufe DW. Mucins in cancer: function, prognosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:874–885. doi: 10.1038/nrc2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacDermed DM, Khodarev NN, Pitroda SP, Edwards DC, Pelizzari CA, Huang L, et al. MUC1-associated proliferation signature predicts outcomes in lung adenocarcinoma patients. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:16–23. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang JH, Hwang SM, Chung IY. S100A8, S100A9 and S100A12 activate airway epithelial cells to produce MUC5AC via extracellular signal-regulated kinase and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways. Immunology. 2015;144:79–90. doi: 10.1111/imm.12352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossi G, Gasser B, Sartori G, Migaldi M, Costantini M, Mengoli MC, et al. MUC5AC, cytokeratin 20 and HER2 expression and K-RAS mutations within mucinogenic growth in congenital pulmonary airway malformations. Histopathology. 2012;60:1133–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roy MG, Livraghi-Butrico A, Fletcher AA, McElwee MM, Evans SE, Boerner RM, et al. Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature. 2014;505:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hata H, Abe R, Hoshina D, Saito N, Homma E, Aoyagi S, et al. MUC5AC expression correlates with invasiveness and progression of extramammary Paget’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:727–732. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu CJ, Yang PC, Shun CT, Lee YC, Kuo SH, Luh KT. Overexpression of MUC5 genes is associated with early post-operative metastasis in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 1996;69:457–465. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961220)69:6<457::AID-IJC7>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seguin L, Desgrosellier JS, Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Integrins and cancer: regulators of cancer stemness, metastasis, and drug resistance. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mariani CR, Falcioni R, Battista P, Zupi G, Kennel SJ, Colasante A, et al. Integrin (alpha 6/beta 4) expression in human lung cancer as monitored by specific monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6107–6112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao X, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase and its signaling pathways in cell migration and angiogenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azim HA, Jr, Ganti AK. Targeted therapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): where do we stand? Cancer Treat Rev. 2006;32:630–636. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lakshmanan I, Seshacharyulu P, Haridas D, Rachagani S, Gupta S, Joshi S, et al. Novel HER3/MUC4 oncogenic signaling aggravates the tumorigenic phenotypes of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;28:21085–21099. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rachagani S, Torres MP, Kumar S, Haridas D, Baine M, Macha MA, et al. Mucin (Muc) expression during pancreatic cancer progression in spontaneous mouse model: potential implications for diagnosis and therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:68–80. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lakshmanan I, Ponnusamy MP, Das S, Chakraborty S, Haridas D, Mukhopadhyay P, et al. MUC16 induced rapid G2/M transition via interactions with JAK2 for increased proliferation and anti-apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:805–817. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seshacharyulu P, Ponnusamy MP, Rachagani S, Lakshmanan I, Haridas D, Yan Y, et al. Targeting EGF-receptor(s) — STAT1 axis attenuates tumor growth and metastasis through downregulation of MUC4 mucin in human pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:5164–5181. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.