Abstract

Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating anxiety disorder resulting from traumatic stress exposure. Females are more likely to develop PTSD than males, but neurobiological mechanisms underlying female susceptibility are lacking. This can be addressed by using nonhuman animal models. Single prolonged stress (SPS), a nonhuman animal model of PTSD, results in cued fear extinction retention deficits and hippocampal glucocorticoid receptor (GR) upregulation in male rats. These effects appear linked in the SPS model, as well as in PTSD. However, the effects of SPS on cued fear extinction retention and hippocampal GRs in female rats remain unknown. Thus, we examined sex differences in SPS-induced cued fear extinction retention deficits and hippocampal GR upregulation. SPS induced cued fear extinction retention deficits in male rats but not female rats. SPS enhanced GR levels in the dorsal hippocampus of female rats, but not male rats. SPS had no effects on ventral hippocampal GR levels, but ventral hippocampal GR levels were attenuated in female rats relative to males. These results suggest that female rats are more resilient to the effects of SPS. The results also suggest that GR upregulation and cued fear extinction retention deficits can be dissociated in the SPS model. Keywords: sex differences, stress, post traumatic stress disorder, extinction recall, fear, glucocorticoids

1Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating anxiety disorder which results from traumatic stress exposure [1]. Females are twice as likely to suffer from PTSD relative to males [2] even though the probability of trauma exposure in females is lower [3]. This suggests that females are more susceptible to the effects of trauma. However, neurobiological mechanisms through which this increased susceptibility manifests have not been sufficiently explored. Nonhuman animal models of PTSD [4], such as the single prolonged stress (SPS) model, can be useful for exploring these mechanisms. Unfortunately, SPS has only been previously conducted in male rats.

Fear extinction retention deficits and enhanced glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression are both symptoms observed in PTSD patients [5–7]. Fear extinction retention deficits refer to the failure to inhibit fear conditioned responding (e.g. conditioned freezing) to a previously extinguished fear conditioned stimulus (CS) [8]. Enhanced GR levels have been implicated in PTSD symptomatology [7], and changes in GR function have been suggested to contribute to trauma susceptibility in females [9]. Fear extinction retention deficits and enhanced hippocampal GR expression are also observed in the SPS model [10, 11], and these two effects may be linked [12]. Thus, examining sex differences in the SPS model with regard to fear extinction retention and GR expression could lead to a better understanding of how GR function contributes to susceptibility to trauma in female humans. The current study examined the effects of SPS on cued fear extinction retention and GR expression in the dorsal hippocampus (dHipp) and ventral hippocampus (vHipp) of male and female rats.

Twenty four male and female Sprague-Dawley Rats were obtained from Charles River (Portage, MI) as subjects. Upon arrival, male (postnatal day (PD) 43–45, 151–175g) and female rats (PD 40–44, 126–150g) were housed in same-sex pairs. Rats were placed on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and allowed ad libitum access to water and 23g/day of standard rat chow per the manufacturer’s recommendation after a five-day acclimation period with ad libitum access to food. All experimental procedures were performed in compliance with approval from The University of Delaware Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee following guidelines established by the NIH.

Vaginal smears were collected from female rats daily using cotton swabs dipped in sterile saline for 14 days prior to any experimental procedures to determine stage of estrus cycle. Loose epithelial cells gathered from swabbing were mounted onto slides to enable visualization under a light microscope. Male rats were swabbed in the anogenital region daily as a control procedure. Females were pseudo-randomly assigned to SPS or control condition based upon stage of estrus cycle such that equal numbers of females in each stage would be present in the SPS and control groups.

Female (PD 58–62) and male (PD 61–63) rats underwent SPS and control procedures as previously described [13]. The SPS procedure was comprised of 120 minutes of restraint, 20 minutes of forced swimming, and ether exposure (70 mL) until general anesthesia was induced. Control animals were left in their home cages in a novel room for the duration of the SPS procedure. Following these procedures, rats were housed individually and allowed an undisturbed post-stress incubation period of seven days because this is necessary to observe SPS effects [11, 14].

Fear conditioning, extinction training, and retention testing protocols were conducted as previously described [12, 14]. Fear conditioning was conducted in Context A and was comprised of five CS-unconditioned stimulus (US) pairings. The CS was a tone (2 kHz, 10s, 80 dB) which co-terminated with the US footshock (1 mA, 1s). Extinction training was conducted 24 hours later in Context B and involved 30 CS-only presentations. Extinction retention testing was conducted in Context B (i.e. the extinction training context) 24 hours after extinction training and involved eight CS-only presentations. This context-shift procedure minimizes the effects of contextual fear conditioning on cued fear and extinction memory phenomena [15]. All behavioral sessions employed a 210s baseline period and 60s inter-trial intervals (ITI). Cameras located on the boxes’ ceilings recorded behavioral videos using Any-maze software (Stoelting Inc.). Videos were scored offline.

One day after cessation of fear extinction retention testing, all rats were sacrificed via rapid decapitation. Western blot electrophoresis was used to assay GR levels as previously described [12]. The hippocampus was divided into the dHipp and vHipp and GR content was analyzed in these brain regions separately. Homogenates from brain samples were electrophoresed on Tris-HCl gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:500 (Santa Cruz biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), M-20) was used to visualize GRs, while mouse monoclonal antibody (1:250–1000 (Santa Cruz biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), C4) was used to visualize the reference protein, β-actin. Fluorescent tagged goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse antibodies were used to visualize primary antibodies (Li-COR, 1:2000). Membranes were scanned on a LI-COR Odyssey CLx scanner and Image Studio software was used to score protein bands. Samples for each subject were run across multiple gels. For each subject, data from all gels were averaged.

Any-maze was used to score freezing in behavioral videos as previously described [12]. Freezing during the CS presentation and the following ITI were blocked into one trial and converted into percentages for statistical analyses. For extinction training and testing, cued freezing during two trials was averaged into one block. All behavioral data was subjected to a stress (SPS vs. control) × sex (male vs. female) × trial or block (1-n) factor design. Main and simple effects were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), while main and simple comparisons were analyzed using a t-test with a Bonferroni correction where necessary.

GR levels were expressed relative to β-actin and subjected to a stress × sex factor design. A second analysis was performed on GR levels, whereby GR levels were normalized relative to the respective control group separately for males and females and then analyzed with a one-sample t-test. P <.05 was set as the threshold to define statistical significance. If data from an animal was at least three standard deviations from its corresponding group mean, the data from this animal was removed from the study. This resulted in three animals being removed from the data set (SPS/male = 1, Control/male = 1, SPS/female = 1).

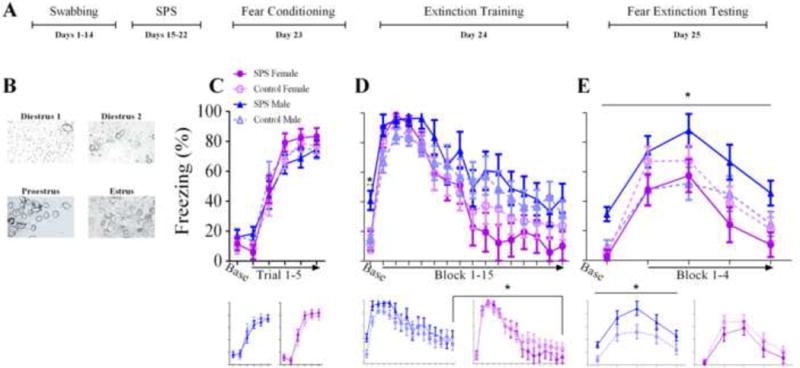

Figure 1A illustrates the experimental design. Figure 1B shows cells from females in different stages of estrous. Chi-square tests revealed that the proportion of females in a particular phase of the estrous cycle (i.e. estrus, diestrus day one, diestrus day two, and proestrus) was equivalent across SPS and all behavioral tests (χ2 (3, N= 22) = .819, p = .845).

Figure 1.

(A) Denotes experimental design. (B) Representative cell types for each stage of the estrus cycle. (C) Acquistion of fear conditioning was not affected by stress or sex. (D, top panel) SPS/males exhibited enhanced freezing to the context during the baseline of extinction training, indicative of deficits in contextual fear memory discrimination. (D, bottom panel) Female rats showed enhanced acquisition of fear extinction relative to male rats as evidenced by lower freezing in the final fear extinction block. (E) Contextual fear discrimination deficits in SPS/males seen in extinction training persisted into the cued fear extinction retention test. SPS/males also showed cued fear extinction retention deficits. Neither of these effects were present in SPS/females. In (C), (D), and (E), the bottom panels show the data for males and females separately. (*) Denotes statistical significance.

ANOVA of cued freezing during fear conditioning revealed a main effect of blocked trial (F(5,145) =179.874, p < .001), which suggests all rats acquired the cued fear memory. There was also a sex × trial interaction (F(5,145) = 2.824, p = .026). Performing a t-test on the difference in cued freezing between trials 5 and 1 revealed that the rise in cued freezing was greater in females relative to males (t(31) = 2.567, p = .034). However, cued freezing during trial 5 was equivalent between male and female rats (t(31) = 1.015, p = .318). These findings suggest that female rats showed a faster rise in levels of cued freezing during fear conditioning, but acquisition of cued fear memory was the same between the sexes (Figure 1C).

ANOVA of freezing during extinction training revealed a main effect of blocked trial (F(15,435) =41.708, p < .001) and a significant effect of trial on the quadratic trend component (F(1,29) =12.134, p = .002), suggesting cued fear memory retrieval and acquisition of cued fear extinction memory occurred in all rats. There was also a main effect of sex (F(1,29) =4.802, p = .037) and sex × trial interaction (F(15,435) =0.351, p = .042). To probe these effects further, different blocks of the extinction training session were separately subjected to a sex × stress factor design. To examine contextual fear discrimination, baseline freezing was subjected to ANOVA. This revealed significant main effects of stress (F(1,29) = 4.625, p = .04) and sex (F(1,29) = 5.969, p = .021) due to enhanced baseline freezing in SPS/males relative to all groups. This reflects contextual fear discrimination deficits in SPS/males. ANOVA of cued freezing during the first two blocks of extinction training was used to assess if SPS or sex had effects on cued fear memory retrieval. No significant effects were observed (p’s > .05). ANOVA of cued freezing during the final extinction training block was performed to examine acquisition of extinction memory. A significant main effect of sex (F(1,29) = 4.238, p = .049) was observed due to enhanced levels of cued freezing in male rats relative to females, which suggests that acquisition of cued extinction memory was enhanced in female rats (Figure 1D).

For fear extinction retention testing, ANOVA of cued freezing revealed a sex × stress interaction (F(1,29) = 5.797, p = .023). There was a simple effect of stress for male rats (F(1,14) = 5.133, p = .04), but not female rats (F(1,15) = 1.192, p = .292). The results suggest that both baseline and cued freezing were enhanced in the SPS/males relative to the control/males; an effect that was absent in female rats. Thus, contextual fear memory discrimination deficits and cued fear extinction retention deficits were observed in SPS/males, but not SPS/females (Figure 1E).

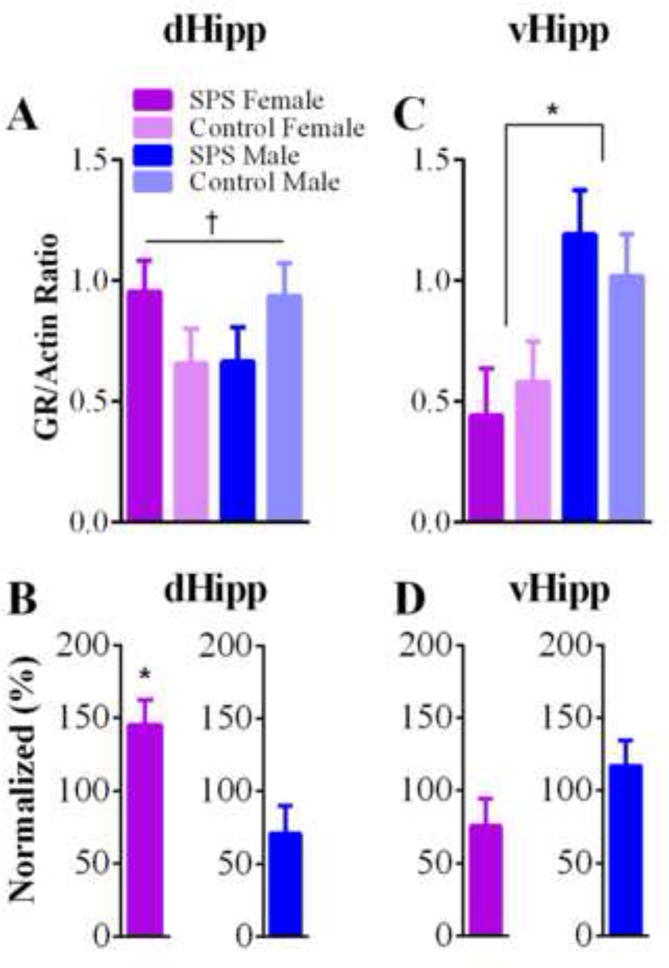

Analysis of dHipp GR levels revealed a stress × sex interaction (F(1,35) = 4.262, p = .046), which suggests that SPS exposure enhanced GR upregulation in female rats, but not male rats. This interpretation was further supported by a t-test performed on SPS/female GR expression in the dHipp using normalized GR levels relative to control/females (t(10) = 2.367, p = .039; see Figure 3C). This t-test on normalized GR levels in SPS/males did not reveal a significant effect (t(8) = −1.849, p = .102). ANOVA of vHipp GR levels yielded a significant main effect of sex (F(1,34) = 10.814, p = .002), but no stress or stress × sex interaction effects (p’s > .05). These analyses reflect the finding that females had lower levels of GRs in the vHipp, but that stress had no effects on vHipp GR levels (Figure 3). This interpretation was further supported by non-significant one-sample t-tests of normalized vHipp GR levels in males and females (p’s > .05). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted for stage of estrus cycle for all ANOVAs reported. None of these yielded a statistically significant result (p’s > .05).

Figure 3.

(A) Females exhibited an upregulation of GRs in the dHipp to SPS exposure, while males did not. (C) Females had lower levels of GRs in the vHipp as compared to male rats. SPS had no effect on GR expression in the vHipp. In (B) and (D), normalized GR levels, relative to the respective sex control (e.g. SPS/male relative to control/male) are shown. (*) Denotes statistical significance. (†) Indicates significant sex by stress interaction.

We demonstrated that SPS exposure does not induce cued fear extinction retention deficits in female rats, but enhances dHipp GR levels in these rats. Females also had lower levels of GRs in the vHipp relative to male rats. While other studies have found lower levels of GRs in females across many brain regions (see [9] for review), to our knowledge this is the first study to find a sex difference in GR expression in the vHipp. We also replicated the finding that SPS exposure in male rats results in cued fear extinction retention deficits.

SPS exposure did not induce cued fear extinction retention deficits in female rats, which suggests female rats are resilient to some of the detrimental effects of SPS. There is precedent in the literature for female resilience to stress when stress paradigms are paired with Pavlovian fear conditioning. For instance, chronic stress exposure results in cued fear extinction retention deficits in male rats, but enhances extinction retention in female rats [16]. Thus, it can be argued that female rats are resilient to the detrimental effects stress has on cued fear extinction retention. In contrast, female humans appear susceptible to effects of traumatic stress [2, 3, 17]. The reason for the apparent discrepancy is unclear. While animal stress models can provide insight into neurobiological mechanisms of trauma susceptibility, differences may exist between rodents and humans that make these animal stress models somewhat ineffective. Alternatively, current animal stress models may be inappropriate for female rats, as female rats may perceive these stressors differently than males. Thus, the development of new stress protocols may be needed.

Upregulation of dHipp GRs in SPS/male rats was not observed, which is inconsistent with previous studies [10–12]. Potential reasons to explain this discrepancy include enhanced levels of handling and older age of rats at SPS exposure in the current study. Because male rats were swabbed daily, levels of handling in this study were enhanced relative to previous studies [12, 14]. Additionally, rats are typically between PD 48–51 when exposed to SPS [12, 14], but rats in this study were between PD 61–63. Irrespective of why hippocampal GR upregulation was not observed with SPS exposure, it is important to note that cued fear extinction retention deficits in SPS-exposed males were still observed (see Results). This suggests that upregulation of hippocampal GRs and cued fear extinction retention deficits can be dissociated in the SPS model. This assertion is further reinforced by the finding that SPS exposure in female rats enhanced dHipp GR levels, but did not induce cued fear extinction retention deficits. Because SPS/females experienced GR upregulation in the dHipp but not cued fear extinction retention deficits, this raises the possibility that GR upregulation could have different effects in males and females. Additionally, results suggest the possibility of a differential role of the dHipp versus vHipp in mediating responses to stress due to SPS-induced GR upregulation occurring in the dHipp but not vHipp. Future research is needed to explore these possibilities.

Why might female rats be resilient to stressors that induce extinction retention deficits in males? Estrogen levels have been shown to contribute to chronic stress resiliency in female rats. Chronically stressed male, but not female, rats’ performance on a prefrontal cortex (PFC)-dependent memory task is compromised. This resiliency in female rats is due to enhanced activation of estrogen receptors in the PFC [18]. Additionally, sex differences in hippocampal structure have been found in response to chronic stress, and estrogen has been shown to play a role in this [19]. We also found a sex difference after stress exposure in the hippocampus, with SPS/females, but not SPS/males, demonstrating GR upregulation in the dHipp (see Results). The ventromedial PFC and hippocampus are critical for fear extinction [8]. Thus, sex differences in structure and/or function of the PFC or hippocampus could explain why female rats do not exhibit extinction retention deficits with stress exposure (see Results; [16]). Because identifying neurobiological mechanisms of resiliency helps develop treatments for stress-induced psychological disorders such as PTSD, future research is needed to explore how resiliency to SPS occurs in female rats.

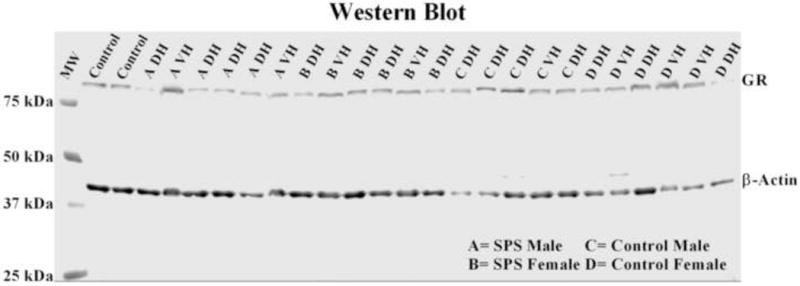

Figure 2.

Representative molecular weight (MW) ladder, GR, and β-actin bands in the vHipp (VH) and dHipp (DH). Positive controls were run in the first two lanes of the gel.

Highlights.

Sex differences in the SPS model of PTSD were examined.

SPS induces extinction retention deficits in male, but not female, rats.

SPS enhanced GR expression in female, but not male, rats.

Female rats are resilient to SPS.

GR upregulation does not always coincide with extinction deficits in the SPS model.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a UDRF award. We would like to thank Steven Albanese, Molly Roberts, and Zoë Corner for their help in conducting this project.

Abbreviations

- PTSD

post traumatic stress disorder

- SPS

single prolonged stress

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- dHipp

dorsal hippocampus

- vHipp

ventral hippocampus

- PD

postnatal day

- CS

conditioned stimulus

- US

unconditioned stimulus

- ITI

inter-trial intervals

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th. This American Psychiatric Association; 2013. (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breslau N, Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Lucia VC, Anthony JC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: a study of youths in urban America. Journal of Urban Health. 2004;81:530–44. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto S, Morinobu S, Takei S, Fuchikami M, Matsuki A, Yamawaki S, et al. Single prolonged stress: toward an animal model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:1110–7. doi: 10.1002/da.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milad MR, Orr SP, Lasko NB, Chang Y, Rauch SL, Pitman RK. Presence and acquired origin of reduced recall for fear extinction in PTSD: results of a twin study. Journal of psychiatric research. 2008;42:515–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yehuda R, Boisoneau D, Mason JW, Giller EL. Glucocorticoid receptor number and cortisol excretion in mood, anxiety, and psychotic disorders. Biological psychiatry. 1993;34:18–25. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Zuiden M, Geuze E, Willemen HL, Vermetten E, Maas M, Heijnen CJ, et al. Pre-existing high glucocorticoid receptor number predicting development of posttraumatic stress symptoms after military deployment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:89–96. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quirk GJ, Garcia R, González-Lima F. Prefrontal mechanisms in extinction of conditioned fear. Biological psychiatry. 2006;60:337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bangasser DA. Sex differences in stress-related receptors: “micro” differences with “macro” implications for mood and anxiety disorders. Biology of sex differences. 2013;4:2. doi: 10.1186/2042-6410-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George S, Rodriguez-Santiago M, Riley J, Rodriguez E, Liberzon I. The effect of chronic phenytoin administration on single prolonged stress induced extinction retention deficits and glucocorticoid upregulation in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology. 2014:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3635-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberzon I, Lopez JF, Flagel SB, Vazquez DM, Young EA. Differential regulation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors mRNA and fast feedback: relevance to post-traumatic stress disorder. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:11–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knox D, Nault T, Henderson C, Liberzon I. Glucocorticoid receptors and extinction retention deficits in the single prolonged stress model. Neuroscience. 2012;223:163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberzon I, Krstov M, Young EA. Stress-restress: effects on ACTH and fast feedback. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997;22:443–53. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knox D, George SA, Fitzpatrick CJ, Rabinak CA, Maren S, Liberzon I. Single prolonged stress disrupts retention of extinguished fear in rats. Learning & memory. 2012;19:43–9. doi: 10.1101/lm.024356.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang Ch, Knapska E, Orsini CA, Rabinak CA, Zimmerman JM, Maren S. Fear extinction in rodents. Current Protocols in Neuroscience. 2009:8.23.1–8.23.17. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0823s47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baran SE, Armstrong CE, Niren DC, Hanna JJ, Conrad CD. Chronic stress and sex differences on the recall of fear conditioning and extinction. Neurobiology of learning and memory. 2009;91:323–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR. Gender differences in susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour research and therapy. 2000;38:619–28. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei J, Yuen EY, Liu W, Li X, Zhong P, Karatsoreos IN, et al. Estrogen protects against the detrimental effects of repeated stress on glutamatergic transmission and cognition. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:588–98. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shors T, Chua C, Falduto J. Sex differences and opposite effects of stress on dendritic spine density in the male versus female hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6292–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06292.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]