Abstract

Uridine diphosphate galactopyranose mutase (UGM also known as Glf) is a biosynthetic enzyme required for construction of the galactan, an essential mycobacterial cell envelope polysaccharide. Our group previously identified two distinct classes of UGM inhibitors; each possesses a carboxylate moiety that is crucial for potency yet likely detrimental for cell permeability. To enhance antimycobacterial potency, we sought to replace the carboxylate with a functional group mimic–an N-acylsulfonamide group. We therefore synthesized a series of N-acylsulfonamide analogs and tested their ability to inhibit UGM. For each inhibitor scaffold tested, the N-acylsulfonamide group functions as an effective carboxylate surrogate. While the carboxylates and their surrogates show similar activity against UGM in a test tube, several N-acylsulfonamide derivatives more effectively block the growth of Mycobacterium smegmatis. These data suggest the replacement of a carboxylate with an N-acylsulfonamide group could serve as a general strategy to augment antimycobacterial activity.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, cell wall polysaccharide, UDP-galactopyranose mutase, galactofuranose, N-acylsulfonamide

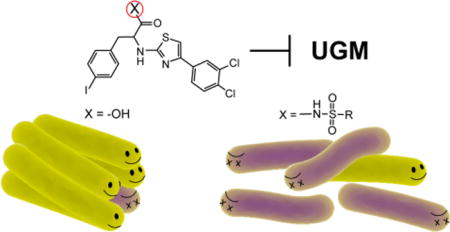

TOC image

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis, is responsible for over one million fatalities each year.1 Combating mycobacterial infections has proved challenging because the bacteria possess a thick, hydrophobic cell wall, which is impenetrable to many common antibiotics. The cell envelope is essential for mycobacterial viability and pathogenesis. Moreover, it is composed of many building blocks unique to microbes,2, 3 rendering the biosynthetic enzymes that assemble this structure attractive potential therapeutic targets.4, 5 The first-line anti-tubercular drugs ethambutol and isoniazid act by inhibiting the formation of the arabinan and mycolic acid components of mycobacteria.6–8 Second-line drugs, such as cycloserine, target peptidoglycan assembly.9 With the emergence of drug-resistant strains of M. tuberculosis, new targets are needed.10, 11 To date, there is one component of the cell envelope whose biosynthesis is not inhibited by existing drugs or potent chemical probes — the galactan.

The galactan is a linear polysaccharide of D-galactofuranose (Galf) residues that extends from the peptidoglycan. The galactan is elaborated with branched arabinan polysaccharide chains, which in turn provide covalent attachment points for the lipophilic mycolic acids. In the absence of the galactan, cell wall construction is halted and mycobacterial growth is compromised.12 Galactan biosynthesis is dependent on production of uridine 5′-diphosphate galactofuranose (UDP-Galf),13 the only known donor substrate for Galf incorporation into glycans. The cytoplasmic enzyme UDP-galactopyranose mutase (UGM, also referred to as Glf) catalyzes the interconversion of UDP-galactopyranose (UDP-Galp) and UDP-Galf, with the equilibrium between these species weighted toward the more stable pyranose form (Figure 1).14, 15 However, organisms that use UDP-Galf generate sufficient quantities to allow Galf incorporation into diverse glycans. Intriguingly, UGM is present in numerous pathogenic species, including bacteria, fungi, and nematodes, yet the enzyme is absent in mammals.3 Our group and others have sought to identify UGM inhibitors.16–23 Such compounds can be used in mycobacteria to evaluate UGM as a novel target and to devise effective probes of galactan assembly.

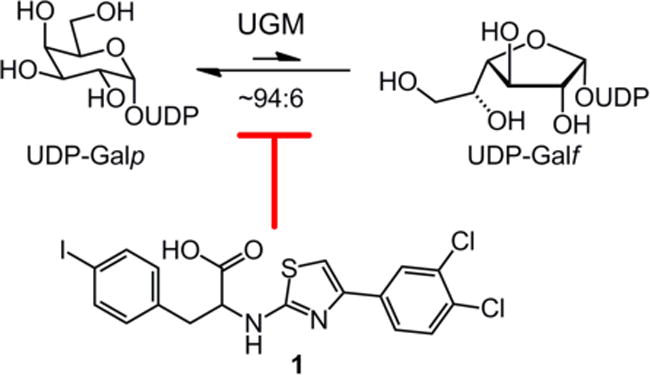

Figure 1.

UDP-galactopyranose mutase catalyzes the interconversion of UDP-Galp and UDP-Galf. 2-Aminothiazole 1 inhibits UGM.

A class of 2-aminothiazoles was previously designed that inhibits M. tuberculosis UGM (MtbUGM) activity and blocks the growth of M. smegmatis.18 The compounds were tested against M. smegmatis, as it is a model mycobacterial species: Its cell envelope architecture is similar to that of M. tuberculosis, yet M. smegmatis grows more rapidly and is non-pathogenic to humans. The most potent analog 1 (Figure 1) of this inhibitor set displays modest antimycobacterial activity. We therefore set out to identify features of the 2-aminothiazole scaffold that could be modified to improve efficacy against mycobacteria.

We focused on the carboxylic acid moiety of 1, which is hypothesized to interact with the MtbUGM active site residues Arg291 and Arg180.15 These arginine residues are conserved across UGM homologs and they interact with the pyrophosphate group of the natural substrates UDP-Galp and UDP-Galf. The observation that the carboxylate moiety of the 2-aminothiazole inhibitors is crucial for activity against UGM suggests that it mimics the pyrophosphate group.18 Still, negatively charged functional groups such as carboxylates are known to hinder diffusion through lipid bilayer membranes.24, 25 We anticipated that replacing the carboxylic acid with a functional group surrogate would modulate the physicochemical properties of the inhibitor and might enhance its ability to permeate mycobacteria. We identified the N-acylsulfonamide functionality as a promising candidate, as it previously has been employed as a carboxylic acid bioisostere26 and can successfully mimic phosphate groups.27, 28 N-Acylsulfonamides have lower pKa values to those of carboxylic acids, and are expected to be ionized under physiological conditions.29 The N-acylsulfonamide group also has an additional substituent (Scheme 1) that could alter overall lipophilicity or engage in additional binding interactions. Additionally, compared with a carboxylate, the anionic charge of N-acylsulfonamides is delocalized over more atoms. We therefore postulated that substitution of a carboxylate with an N-acylsulfonamide group could improve antimycobacterial efficacy while facilitating interactions crucial for UGM active site binding.

Scheme 1. Late-stage carboxylate modification to generate N-acylsulfonamides.

Abbreviations: CDI ≡ 1,1-carbonyldiimidazole, DBU ≡ 1,8-diazabicycloundec-7-ene

Our strategy was to implement a late-stage functionalization of the most potent 2-aminothiazole derivative 1 to generate a collection of N-acylsulfonamide analogs. Coupling of 1 to a range of commercially available sulfonamides yielded the desired N-acylsulfonamides 2–9 (Scheme 1).30 For comparison, a methyl ester variant, 10, was synthesized. We hypothesized that replacing the carboxylate with a charge-neutral ester species would significantly diminish inhibitor potency. In contrast, the modification with N-acylsulfonamide groups should result in inhibitory potencies comparable or superior to that of the carboxylate.

To explore the effect of carboxylate modifications, MtbUGM activity was compared in the presence of 50 μM of compound 1, 2, or 10 (Figure 2). Each compound was tested for its ability to block MtbUGM31 from generating UDP-Galp from UDP-Galf.22 We employed conditions under which free carboxylate 1 inhibited greater than 90% of UGM activity. The methylsulfonamide-modified 2 also displayed excellent levels of inhibition (>90%). In contrast, methyl ester 10 inhibited only 20% of activity, suggesting the carboxylate anion is important for inhibitor potency. These data supported our hypothesis that the negatively charged carboxylate can replace the pyrophosphate binding in the active site, and that the anionic N-acylsulfonamide can preserve the interactions critical for binding affinity.

Figure 2.

Comparison of inhibitor potency between 2-aminothiazoles with carboxyl replacements. Inhibition of MtbUGM was evaluated in the presence of 50 μM compound. Error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean (n = 3)

To further characterize the consequence of carboxylate replacement, we generated full inhibition curves for each N-acylsulfonamide derivative and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated. The IC50 values for compounds 2–9 were comparable to that of the precursor 1 (IC50 = 6 μM), and they range from 1 – 18 μM (Table 1). The results indicate that the N-acylsulfonamide modification is not only tolerated by the UGM active site, but in some cases can impart enhanced potency. Specifically, compounds 5 and 7–9, which have substituents that can occupy an extended binding site,23 are more potent than is carboxylate 1. Though it is difficult to deconvolute the electronic and steric contributions of aryl substituents on the N-acyl sulfonamide, they do impact the ability of compounds to block the enzyme.

Table 1. In vitro.

inhibition of MtbUGM by Compounds 1–9.

| Compound | R | IC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | 6 ± 2 |

| 2 | CH3 | 12 ± 5 |

| 3 | CF3 | 16 ± 10 |

| 4 | Ph | 7 ± 2 |

| 5 | 4-NO2-Ph | 4 ± 1 |

| 6 | 4-OCH3-Ph | 18 ± 9 |

| 7 | 4-CH3-Ph | 1 ± 1 |

| 8 | 4-Cl-Ph | 3 ± 1 |

| 9 | 2-NO2-Ph | 2 ± 1 |

Relative activity of recombinant MtbUGM was evaluated for a range of inhibitor concentrations.

We carried out additional studies to evaluate whether the observed inhibitory potencies arise from specific binding to UGM. Studies by Shoichet and co-workers have revealed the importance of testing for small molecules for aggregation, as compounds with this propensity can act as non-selective inhibitors.32–34 We therefore routinely assess the aggregation propensity of a representative set of compounds (in this case, 1, 2, and 4) using dynamic light scattering (DLS). No aggregation was observed for any of these compounds at concentrations up to 50 μM (Table S1), a concentration well above the IC50 values of the inhibitors. These data indicate that the N-acylsulfonamide analogs specifically inhibit UGM.

The effectiveness of compounds 2–9 in inhibiting UGM catalysis led us to test whether they act on mycobacteria. Growth inhibition of M. smegmatis was assessed in liquid culture using a microplate Alamar Blue assay,35, 36 and from these data the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined for each compound (Table 2). The most potent inhibitors in liquid culture conditions were the N-acylsulfonamides 4 and 7–9, each of which was at least four-fold more effective than the carboxylic acid precursor 1. Thus, compounds 7–9 were not only more effective than 1 at blocking UGM activity but also had higher antimycobacterial activity.

Table 2. M. smegmatis.

growth inhibition by Compounds 1–9

| Compound | R | MIC (μM)a | Inhibition zone (mm)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | 50 | 5.0 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | CH3 | 25 | 7.0 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | CF3 | 25 | 7.7 ± 0.6 |

| 4 | C6H5 | 12 | 7.3 ± 0.6 |

| 5 | 4-NO2-C6H4 | 50 | 4.2 ± 0.3 |

| 6 | 4-OCH3-C6H4 | 25 | 6.0 ± 0.1 |

| 7 | 4-CH3-C6H4 | 12 | 6.0 ± 0.6 |

| 8 | 4-Cl-C6H4 | 6 | 6.3 ± 0.6 |

| 9 | 2-NO2-C6H4 | 12 | 5.7 ± 0.1 |

Inhibition of M. smegmatis growth in liquid media. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values were defined as the concentration at which at least 90% of growth inhibition was observed. Inhibition values are based on two independent experiments, each including

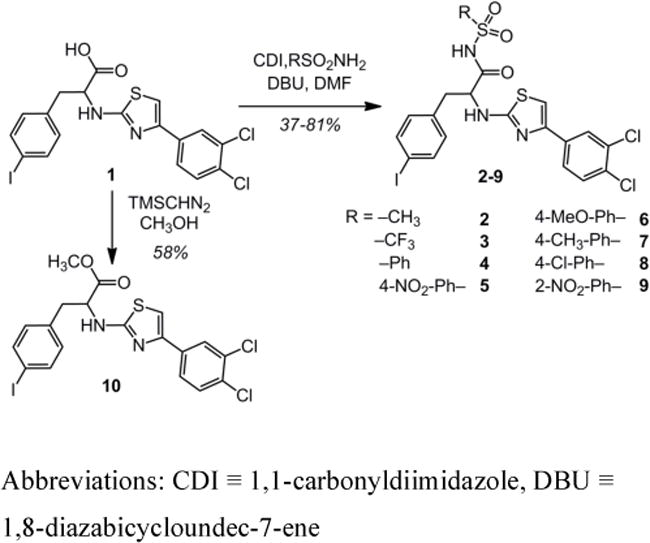

On solid media, growth inhibition was evaluated using an agar disk diffusion assay (Table 2; Figure 3).18 The observed activity of the compounds in this disk diffusion assay is a function of that compound’s ability to diffuse through the agar and its growth inhibitory activity. We tested the carboxylic acid 1, the N-acylsulfonamides and methyl ester 10. Though methyl ester 10 itself is not a useful UGM inhibitor, if mycobacteria possess nonspecific esterases, it could be converted to the more potent acid 1. When the methyl ester variant 10 was tested, no mycobacterial growth inhibition was observed. In contrast to the results with ester 10, all N-acylsulfonamides except 5 exhibited more potent growth inhibition than did 1, with compound 3 as the most efficacious. Each inhibitor was also evaluated against Escherichia coli BL21, a bacterial strain lacking a UGM. No antibacterial activity was observed against E. coli by any of the compounds tested (Figure S1). The specificity of these inhibitors for UGM-dependent bacteria is consistent with UGM inhibition leading to antimycobacterial activity.

Figure 3.

Agar disk diffusion assay with M. smegmatis and compounds 1–10 (15 nmols). Representative images are shown. Quantification of growth inhibition zones can be found in Table 2 (n = 3).

We postulated that a contributing factor in superior growth inhibition of M. smegmatis by N-acylsulfonamide derivatives is their increased ability to penetrate the mycobacterial cell envelope. Such a model could explain why compounds 2, 3, and 6 are 2–3-fold poorer than carboxylate 1 at blocking UGM enzyme activity, yet they are more effective at blocking mycobacterial growth. To test whether elaboration of a carboxylate to an N-acylsulfonamide moiety influences cell uptake, we compared the intracellular accumulation of compounds 1 and 2. Quantification by LC-MS has been utilized by others to rationalize differences in inhibitor potency between enzyme assays and in cellulo experiments.37, 38 Using a protocol developed by Chatterji and coworkers,39 we evaluated compound accumulation in M. smegmatis, upon treatment with 25 μM of either 1 or 2. The level of cell-associated 2 was approximately 14-fold higher than that of 1. These results indicate that N-acylsulfonamide modification can facilitate the passage of small molecules through the mycobacterial cell envelope.

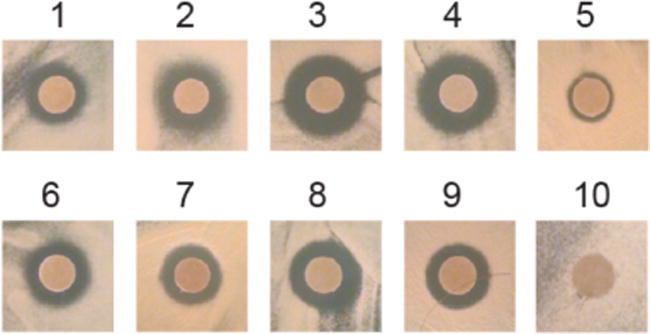

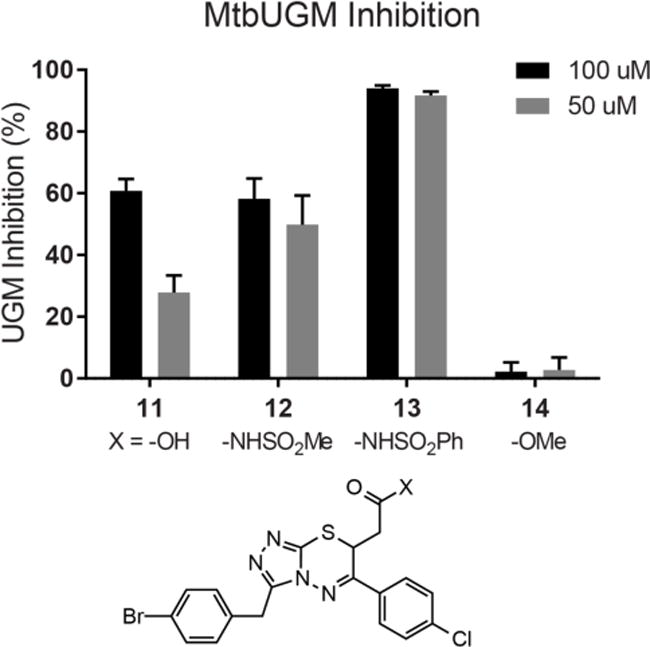

If the role of the N-acylsulfonamide group is to mimic the carboxylate, it might serve as a general surrogate. To test this possibility, we extended our studies to an additional inhibitor scaffold that was identified through virtual screening.23 Triazolothiadiazine derivatives can block UGM activity and, like the 2-aminothiazoles, they feature a carboxylate. Utilizing an analogous synthetic approach as with the 2-aminothiazoles, lead inhibitor 11 was converted into N-acylsulfonamide derivatives 12 and 13 as well as methyl ester 14. Evaluation of these analogs in the UGM activity assay revealed trends in potency that mirrored those of the 2-aminothiazole inhibitor variants (Figure 4). With a co-crystal structure of a triazolothiadiazine inhibitor in hand, we evaluated the fit of 12 and 13 into the UGM active site. Several predicted docking poses mimic the binding pose of the crystal structure, and illustrate that the additional steric demands of an arylsulfonamide may be accommodated by the active site (Figures S2–5). These results indicate that our strategy can be employed to improve the activity of UGM inhibitors, and perhaps is applicable to an even broader array of carboxylate-containing antimycobacterial agents.

Figure 4.

Comparison of inhibitor potency between triazolothiadiazines with carboxyl replacements. Inhibition of MtbUGM was evaluated in the presence of 100 or 50 μM inhibitor. IC50 values for 11, 12, and 13 were 80±2, 108±42, and 19±6 μM, respectively. Error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean (n = 2).

The development of small molecules that can permeate cell membranes poses a challenge for medicinal chemistry and chemical biology.40–44 One strategy commonly implemented in eukaryotic cells is to temporarily mask polar groups such as carboxylates via esterification, which promotes passage through the cell membrane.45, 46 Upon reaching the cell’s interior the polar group can be unmasked by esterases, thereby generating the active small molecule.47–49 This strategy relies on the presence of highly promiscuous esterases within the cell that can process the compound of interest.46 Mycobacteria are known to produce lipases 50–52, but the complete lack of activity of methyl ester 10 indicates that they lack indiscriminate enzymes that hydrolyze simple esters. Consequently, alternative approaches to circumvent the permeability barrier are required.

Our data indicate that the N-acylsulfonamide moiety is an apt carboxylate surrogate for UGM inhibitor scaffolds. This modification confers increased potency against UGM activity and in mycobacterial growth assays. Indeed, the ability of the N-acylsulfonamide moiety to enhance small molecule cell permeability is advantageous. The ability of 2-aminothiazoles to inhibit UGM homologs from other organisms has been previously established, including nematodes such as C. elegans, a species in which carboxylate-containing small molecules generally lack biological activity.53 N-Acylsulfonamide-based inhibitors are expected to provide further utility in studying the consequences of Galf depletion in a wide range of prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms.17, 44

Methods

Compound Synthesis

The carboxylate 2-aminothiazole was synthesized according to previously published protocols (Scheme S1).18 Synthetic procedures for carboxylate modification to either N-acylsulfonamide or ester derivatives can be found in the Supporting Information.

Evaluation of MtbUGM Activity

Recombinant MtbUGM was produced according to published protocols, and enzyme activity was evaluated using a previously published HPLC assay.31 Briefly, MtbUGM was incubated in sodium phosphate buffer with sodium dithionite and the substrate UDP-Galf in the absence or presence of an inhibitor (added as a DMSO stock at a final concentration of 1% DMSO). After a 40 second incubation, the reaction was quenched and the aqueous portion was separated and analyzed on a Dionex Carbopac PA-100 column to quantify conversion of UDP-Galf to UDP-Galp. Relative enzyme activity was derived by normalizing activity in the presence of inhibitors against the activity of the enzyme alone.

Mycobacterial Growth Inhibition (Liquid Culture)

M. smegmatis was grown to saturation at 37 °C in Middlebrook 7H9 media with Albumin Dextrose Catalase (ADC) enrichment and 0.05% Tween80. The culture was diluted to OD600 = ~0.02 in LB liquid media and added to 96-well plates with added inhibitor concentrations in twofold dilutions. After 24 hours at 37 °C in a shaking incubator, bacterial growth was evaluated using an AlamarBlue reagent (Invitrogen).

Mycobacterial Growth Inhibition (Solid Culture)

A dense culture of M. smegmatis was diluted to OD600 = ~0.2 in LB liquid media and spread onto LB agar plates. Sterile disks (3 mm diameter) were impregnated with a solution of inhibitor in DMSO (15 nmols) and placed on top of the bacterial lawn. After 72 hours incubation at 37 °C, zones of inhibition were measured as the average diameter of the region around a cloning disk where bacterial growth was not visible.

LC-MS Quantification of Compound Accumulation

A dense culture of M. smegmatis was grown in Middlebrook 7H9 media with Albumin Dextrose Catalase (ADC) enrichment and 0.05% Tween80, then cells were pelleted and resuspended in PBS buffer. Cells were incubated at room temperature for 4 hours in the presence of 25 μM inhibitor, then washed and lysed according to the protocol by Chatterji and coworkers.39 Cell lysate was analyzed by LC-MS to quantify levels of accumulated compound.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-AI063596). V.J.W. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1256259). We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Gregory Barrett-Wilt for invaluable assistance with the LC-MS analysis of intracellular compound accumulation. We thank Virginia Kincaid for protein production, and acknowledge V.K., Darryl Wesener, Phillip Calabretta, Heather Hodges, and Dr. Robert Brown for helpful comments and suggestions. NMR and MS instrumentation in the UW–Madison Chemistry Instrument Center is supported by the NSF (CHE-1048642) and the NIH (1S10 0D020022), and by a generous gift from Paul J. Bender. Instrumentation in the UW–Madison Biotechnology Center Mass Spectrometry Facility is supported by the NIH (P50 GM64598, R33 DK070297) and the NSF (DBI-0520825, DBI-9977525).

Abbreviations

- Galf

D-galactofuranose

- M. tuberculosis

Mtb

- UDP-Galp

UDP-galactopyranose

- UGM

UDP-galactopyranose mutase

- DLS

dynamic light scattering

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- LC-MS

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Syntheses and characterization data of all new compounds, DLS aggregation data, molecular docking, and experimental details of the UGM activity assay, the microplate AlamarBlue assay, the agar disk diffusion assay, and the LC-MS compound accumulation assay (PDF).

This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/

Author Contributions:

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis report 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houseknecht JB, Lowary TL. Chemistry and biology of arabinofuranosyl- and galactofuranosyl-containing polysaccharides. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5:677–682. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richards MR, Lowary TL. Chemistry and biology of galactofuranose-containing polysaccharides. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology. 2009;10:1920–1938. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee D. The mycobacterial cell wall: structure, biosynthesis and sites of drug action. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1997;1:579–588. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(97)80055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan PJ. Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2003;83:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belanger AE, Besra GS, Ford ME, Mikusova K, Belisle JT, Brennan PJ, Inamine JM. The embAB genes of Mycobacterium avium encode an arabinosyl transferase involved in cell wall arabinan biosynthesis that is the target for the antimycobacterial drug ethambutol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11919–11924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikusova K, Slayden RA, Besra GS, Brennan PJ. Biogenesis of the mycobacterial cell wall and the site of action of ethambutol. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2484–2489. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.11.2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee A, Dubnau E, Quemard A, Balasubramanian V, Um KS, Wilson T, Collins D, de Lisle G, Jacobs WR., Jr inhA, a gene encoding a target for isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science (New York, NY) 1994;263:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8284673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruning JB, Murillo AC, Chacon O, Barletta RG, Sacchettini JC. Structure of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis D-alanine:D-alanine ligase, a target of the antituberculosis drug D-cycloserine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:291–301. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00558-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koul A, Arnoult E, Lounis N, Guillemont J, Andries K. The challenge of new drug discovery for tuberculosis. Nature. 2011;469:483–490. doi: 10.1038/nature09657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zumla A, Nahid P, Cole ST. Advances in the development of new tuberculosis drugs and treatment regimens. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:388–404. doi: 10.1038/nrd4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan F, Jackson M, Ma Y, McNeil M. Cell wall core galactofuran synthesis is essential for growth of mycobacteria. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3991–3998. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.13.3991-3998.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowary TL. Synthesis and conformational analysis of arabinofuranosides, galactofuranosides and fructofuranosides. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:749–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soltero-Higgin M, Carlson EE, Gruber TD, Kiessling LL. A unique catalytic mechanism for UDP-galactopyranose mutase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nsmb772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chad JM, Sarathy KP, Gruber TD, Addala E, Kiessling LL, Sanders DA. Site-directed mutagenesis of UDP-galactopyranose mutase reveals a critical role for the active-site, conserved arginine residues. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6723–6732. doi: 10.1021/bi7002795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liautard V, Desvergnes V, Martin OR. Stereoselective synthesis of alpha-C-Substituted 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-galactitols. Toward original UDP-Galf mimics via cross-metathesis. Org Lett. 2006;8:1299–1302. doi: 10.1021/ol053078z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caravano A, Dohi H, Sinay P, Vincent SP. A new methodology for the synthesis of fluorinated exo-glycals and their time-dependent inhibition of UDP-galactopyranose mutase. Chem Eur J. 2006;12:3114–3123. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dykhuizen EC, May JF, Tongpenyai A, Kiessling LL. Inhibitors of UDP-galactopyranose mutase thwart mycobacterial growth. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6706–6707. doi: 10.1021/ja8018687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Bkassiny S, N’Go I, Sevrain CM, Tikad A, Vincent SP. Synthesis of a novel UDP-carbasugar as UDP-galactopyranose mutase inhibitor. Org Lett. 2014;16:2462–2465. doi: 10.1021/ol500848q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veerapen N, Yuan Y, Sanders DA, Pinto BM. Synthesis of novel ammonium and selenonium ions and their evaluation as inhibitors of UDP-galactopyranose mutase. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339:2205–2217. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scherman MS, Winans KA, Stern RJ, Jones V, Bertozzi CR, McNeil MR. Drug targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell wall synthesis: development of a microtiter plate-based screen for UDP-galactopyranose mutase and identification of an inhibitor from a uridine-based library. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:378–382. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.1.378-382.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soltero-Higgin M, Carlson EE, Phillips JH, Kiessling LL. Identification of inhibitors for UDP-galactopyranose mutase. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10532–10533. doi: 10.1021/ja048017v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kincaid VA, London N, Wangkanont K, Wesener DA, Marcus SA, Heroux A, Nedyalkova L, Talaat AM, Forest KT, Shoichet BK, Kiessling LL. Virtual Screening for UDP-Galactopyranose Mutase Ligands Identifies a New Class of Antimycobacterial Agents. ACS Chem Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klemm AR, Pell KL, Anderson LM, Andrew CL, Lloyd JB. Lysosome membrane permeability to anions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1373:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walter A, Gutknecht J. Monocarboxylic acid permeation through lipid bilayer membranes. J Membr Biol. 1984;77:255–264. doi: 10.1007/BF01870573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballatore C, Huryn DM, Smith AB., 3rd Carboxylic acid (bio)isosteres in drug design. ChemMedChem. 2013;8:385–395. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201200585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thiyagarajan N, Smith BD, Raines RT, Acharya KR. Functional and structural analyses of N-acylsulfonamide-linked dinucleoside inhibitors of RNase A. FEBS J. 2011;278:541–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07976.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somu RV, Boshoff H, Qiao C, Bennett EM, Barry CE, Aldrich CC. Rationally Designed Nucleoside Antibiotics That Inhibit Siderophore Biosynthesis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Chem. 2006;49:31–34. doi: 10.1021/jm051060o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King JF. Sulphonic Acids, Esters and their Derivatives (1991) John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2006. Acidity; pp. 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronn R, Sabnis YA, Gossas T, Akerblom E, Danielson UH, Hallberg A, Johansson A. Exploration of acyl sulfonamides as carboxylic acid replacements in protease inhibitors of the hepatitis C virus full-length NS3. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:544–559. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carlson EE, May JF, Kiessling LL. Chemical probes of UDP-galactopyranose mutase. Chem Biol. 2006;13:825–837. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seidler J, McGovern SL, Doman TN, Shoichet BK. Identification and prediction of promiscuous aggregating inhibitors among known drugs. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4477–4486. doi: 10.1021/jm030191r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng BY, Shelat A, Doman TN, Guy RK, Shoichet BK. High-throughput assays for promiscuous inhibitors. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:146–148. doi: 10.1038/nchembio718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGovern SL, Caselli E, Grigorieff N, Shoichet BK. A common mechanism underlying promiscuous inhibitors from virtual and high-throughput screening. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2002;45:1712–1722. doi: 10.1021/jm010533y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collins L, Franzblau SG. Microplate alamar blue assay versus BACTEC 460 system for high-throughput screening of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1004–1009. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magnet S, Hartkoorn RC, Szekely R, Pato J, Triccas JA, Schneider P, Szantai-Kis C, Orfi L, Chambon M, Banfi D, Bueno M, Turcatti G, Keri G, Cole ST. Leads for antitubercular compounds from kinase inhibitor library screens. Tuberculosis. 2010;90:354–360. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis TD, Gerry CJ, Tan DS. General platform for systematic quantitative evaluation of small-molecule permeability in bacteria. ACS chemical biology. 2014;9:2535–2544. doi: 10.1021/cb5003015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bockman MR, Kalinda AS, Petrelli R, De la Mora-Rey T, Tiwari D, Liu F, Dawadi S, Nandakumar M, Rhee KY, Schnappinger D, Finzel BC, Aldrich CC. Targeting Mycobacterium tuberculosis Biotin Protein Ligase (MtBPL) with Nucleoside-Based Bisubstrate Adenylation Inhibitors. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2015;58:7349–7369. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhat J, Narayan A, Venkatraman J, Chatterji M. LC-MS based assay to measure intracellular compound levels in Mycobacterium smegmatis: linking compound levels to cellular potency. Journal of microbiological methods. 2013;94:152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikaido H. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:593–656. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.593-656.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delcour AH. Outer membrane permeability and antibiotic resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794:808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rafi SB, Hearn BR, Vedantham P, Jacobson MP, Renslo AR. Predicting and improving the membrane permeability of peptidic small molecules. J Med Chem. 2012;55:3163–3169. doi: 10.1021/jm201634q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walter A, Gutknecht J. Permeability of small nonelectrolytes through lipid bilayer membranes. J Membr Biol. 1986;90:207–217. doi: 10.1007/BF01870127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orsi M, Sanderson WE, Essex JW. Permeability of small molecules through a lipid bilayer: a multiscale simulation study. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:12019–12029. doi: 10.1021/jp903248s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell CT, Sampathkumar SG, Yarema KJ. Metabolic oligosaccharide engineering: perspectives, applications, and future directions. Mol BioSyst. 2007;3:187–194. doi: 10.1039/b614939c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lavis LD. Ester bonds in prodrugs. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:203–206. doi: 10.1021/cb800065s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liederer BM, Borchardt RT. Enzymes involved in the bioconversion of ester-based prodrugs. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95:1177–1195. doi: 10.1002/jps.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Redinbo MR, Potter PM. Keynote review: Mammalian carboxylesterases: From drug targets to protein therapeutics. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:313–325. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03383-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Satoh T, Hosokawa M. Structure, function and regulation of carboxylesterases. Chem-Biol Interact. 2006;162:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deb C, Daniel J, Sirakova TD, Abomoelak B, Dubey VS, Kolattukudy PE. A novel lipase belonging to the hormone-sensitive lipase family induced under starvation to utilize stored triacylglycerol in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3866–3875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505556200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniel J, Maamar H, Deb C, Sirakova TD, Kolattukudy PE. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Uses Host Triacylglycerol to Accumulate Lipid Droplets and Acquires a Dormancy-Like Phenotype in Lipid-Loaded Macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002093. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tallman KR, Levine SR, Beatty KE. Profiling Esterases in Mycobacterium tuberculosis Using Far-Red Fluorogenic Substrates. ACS Chem Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burns AR, Wallace IM, Wildenhain J, Tyers M, Giaever G, Bader GD, Nislow C, Cutler SR, Roy PJ. A predictive model for drug bioaccumulation and bioactivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:549–557. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.