Abstract

Analgesics are commonly used by older adults, raising the question of whether their use might contribute to dementia risk and neuropathologic changes of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study is a population-based study of brain aging and incident dementia among people 65 years or older who are community dwelling and not demented at entry. Amyloid beta 42 and phospho-tau were quantified using Histelide in regions of cerebral cortex from 420 brain autopsies. Total standard daily doses (SDDs) of prescription opioid and non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) exposure during a defined 10-year exposure window were identified using automated pharmacy dispensing data and used to classify people as having no/low, intermediate, or high exposure. People with high NSAID exposure had significantly greater amyloid beta 42 concentration in middle frontal gyrus and superior and middle temporal gyri, but not inferior parietal lobule; no amyloid beta 42 regional concentration was associated with prescription opioid usage. People with high opioid usage had significantly greater concentration of phospho-tau in middle frontal gyrus than people with little-to-no opioid usage. Consistent with our previous studies, findings suggest that high levels of NSAID use in older individuals may promote amyloid beta 42 accumulation in cerebral cortex.

Keywords: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, Alzheimer’s disease, neuropathology, amyloid beta

INTRODUCTION

Analgesics are commonly used medications, particularly among older adults, raising the question of whether the use of these drugs has long term effects, such as contributing to dementia risk and neuropathologic changes of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). The Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study is a population-based study of brain aging and incident dementia among members of Kaiser Permanente Washington (formerly Group Health) in the Seattle area who are 65 years or older and not demented at entry [1–3]. In contrast to several earlier epidemiologic studies, which concluded that protracted use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) was associated with decreased subsequent risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia [4–6], ACT investigators observed that high NSAID usage was associated with increased risk for clinical diagnosis of AD dementia relative to low usage (hazard ratio = 1.55, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07–2.24) among 2095 ACT participants [7]. CI is defined as frequency of possible confidence intervals that contain the true value of the corresponding parameter [8]. Consistent with this observation from ACT, clinical trials looking at rofecoxib, celecoxib and naproxen in older cohorts showed that exposure to NSAIDs increased risk of progression to dementia [9–11]. One year later, in an attempt to refine our understanding of the association between NSAID usage and risk of AD dementia in the ACT cohort, we investigated the association between NSAID usage and the risk of six different neuropathologic lesions including the two hallmark features of AD, neuritic plaques (NPs) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), in the 257 eligible study participants who by that time had donated their brain for research. NP score is a semi-quantitative assessment using CERAD criteria [12]. Using similar definitions for NSAID usage as the ACT clinical study, we observed an elevated relative risk (RR), defined as the ratio of the probability of an event occurring, only for severe NP score with high NSAID exposure (RR 2.37; 95% CI 1.24–4.67) [13].

Recently, ACT investigators expanded their investigation of potential relationships between analgesic usage and AD by investigating the association of prescription opioid usage with the risk of AD dementia and neuropathologic changes including scores for NPs or NFTs [14, 15]. Although opioid usage had a modest association with dementia (hazard ratio [HR] 1.29 with 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–1.62 comparing heavy use to little or no use), we found no association between opioid exposure and either NP or NFT scores. In contrast, people with heavy NSAID use were again observed to have increased risk of high NP score compared to those with little to no use, confirming findings from our prior study of a smaller sample [13–15].

All previous investigations of analgesics and neuropathologic changes in aging brains have used consensus histopathologic scoring, which is convenient because all cases with formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks can be included, but is also limited because the methods are semi-quantitative, generate only a single score for the entire brain, have significant ceiling effects, and lack molecular specificity. The present study’s primary goal was to gain insight into molecular changes of AD in association with sustained use of different analgesics. We estimated the association between these molecular changes and NSAID and opioid exposure (examining both medications to address confounding by indication) and used a novel assay that provides regional quantitative data on Aβ peptides and phospho-tau (phospho-τ) to address the limitations of data derived from histopathologic scoring [16, 17]. Among the family of Aβ peptides, we focused on Aβ42 because abundant observational and experimental data highlight its proximate role in neuron stress and injury [18].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview

This study uses data from autopsied participants from a prospective cohort study of older adults, the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study, which is set within Kaiser Permanente Washington (KP) (formerly Group Health), an integrated healthcare delivery system in the Northwest U.S. Study procedures have been previously described [1]; we briefly summarize them below. Primary analyses include ACT participants who died and underwent autopsy. However, to account for potential selection bias that may result from differences between these participants and those who were not autopsied, we also used data from the full ACT study cohort to inform statistical methods that can help account for selection bias [19]. As such, both populations are described below. Study procedures are approved by KP’s Human Subjects Review Committee, and participants provide written informed consent.

Study Population

ACT enrolls community dwelling KP members living in or near Seattle, Washington who are aged 65+ and non-demented. After a baseline visit, participants are followed biennially with an interview, cognitive screening, and physical measurements. ACT previously enrolled cohorts during the years 1994–1996 and then 2000–2003, and since 2004 the study has maintained an ongoing recruitment process to attempt to maintain an active cohort of approximately 2,000 people undergoing follow-up for incident dementia. Our current study included participants who had at least one follow-up visit beyond ACT study baseline and were enrolled continuously in KP for the 10 year medication exposure window of interest (discussed later below). From participants meeting these criteria, we identified an analytic sample of 420 people who underwent brain autopsy and had undergone medical record review, a protocol performed by ACT that provides important covariate data.

Exposure

Exposure to prescription opioids and prescription non-aspirin NSAIDs was based on prescription fills recorded in the KP automated pharmacy dispensing data. Using information on the medication ingredient, strength, and number of pills dispensed, along with conversion factors, we converted prescription fills to standardized daily doses (SDDs) as in prior studies [14, 15, 20]. To clarify interpretation, 1 SDD of opioids in this study is equivalent to 30 mg morphine, while 1 SDD of NSAIDs is equivalent to 1200 mg ibuprofen. For our analyses, we computed each participant’s total standardized daily doses (TSDDs) of opioid and NSAID exposure by summing the SDDs for all dispensings of these medications in the exposure window of interest, a window which we now describe below.

In specifying the time window in which opioid and NSAID exposure would be measured, we wanted to ensure a sufficiently long period that could reasonably be expected to capture a person’s long-term cumulative medication exposure but that was not so long as to hurt the size of the sample eligible for analysis, as each included subject would need to have been continuously enrolled in the health plan during that time in order to assess their exposure. Further, we wanted an exposure window that only considered medication usage occurring prior to any dementia onset, as one could argue that such a period is the most etiologically relevant for the targeted associations of interest [15]. Thus to achieve this, we decided on a 10-year exposure window that covered the period from 11 years prior to dementia onset through 1 year prior to onset. Medication used during the year immediately preceding dementia onset was excluded because prodromal symptoms of dementia could affect medication usage. For participants in our analysis who had not been observed to develop dementia, we needed a comparable “index date” relative to which we would measure exposure; therefore, they were assigned such a date based on matching to those with dementia (using age and year of death or ACT enrollment;, see [15] for additional details).

For NSAIDs, usage groups were defined as no/low (0 to 60 TSDDs), intermediate (61 to 540 TSDDs), or high exposure (>540 TSDDs). For prescription opioids, the three usage groups were defined as no/low (0 to 10 TSDDs), intermediate (11 to 90 TSDDs), or high (>90 TSDDs). To provide clinical perspective on these groupings, an individual could reach the highest level of prescription opioid exposure by using the equivalent of 30 mg of morphine daily for more than 3 months, and one could reach the highest NSAID exposure category by using the equivalent of 1200 mg of ibuprofen daily for approximately 1.5 years [15]. Analyses of associations between medication exposure levels and outcomes of interest utilized information on the ACT participants who came to autopsy and underwent medical record review, while information on the broader ACT cohort who were not included in the autopsy sample was used to adjust (weight) estimates to account for potential selection bias.

A potential concern is that certain NSAIDs available over the counter (OTC) might be excluded from the automated pharmacy dispensing data. To understand the extent of this potential bias, we found that 14.5% of the 420 ACT subjects used OTC NSAIDs use during the relevant window period. Also of note is that 39.3% of the 14.5% of ACT subjects that self-reported OTC NSAID use during the relevant window period were already categorized as being in the group of the heaviest NSAID users. Thus, at most, 37 ACT subjects could have been misclassified as having a lower exposure level than they actually had. Realistically, the number of misclassified subjects is probably even less because some of these subjects were likely captured using the available pharmacy and claims information. Additionally, nearly all subjects with substantial self-reported OTC NSAID use (defined as those reporting OTC NSAID use at 2 or 3 separate ACT visits) were already classified as heavy users and were rarely seen in the low/no use group. Furthermore, missing some OTC NSAID use does not necessarily mean that someone would have been moved into a higher NSAID exposure category group (as defined above).

Histelide Quantification

We quantified regional concentration of Aβ42 (Covance Research Products, SIG-39320, Clone 6E10, Mouse monoclonal 1:4000) and Phospho-τ (Thermo Scientific, MN1020, Clone AT8, Mouse monoclonal 1:100) in middle frontal gyrus (MFG), superior and middle temporal gyri (SMTG), and inferior parietal lobule (IPL) exactly according to a method pioneered in our laboratory to obtain quantitative molecular data from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue that we call Histelide, for “histology and ELISA on a glass slide” [21]; antibody specificity is reported in Table 2 of this publication [21]. We have shown previously in the same autopsy brain regions that Histelide has a linear concentration response, and that regions of brain from control cases that lacked phospho-τ or Aβ42 deposition did not produce signal above noise [21]. Furthermore, Histelide measurements of phospho-τ correlate with Braak stage for neurofibrillary degeneration and Histelide measurements of Aβ42 correlate with CERAD NP score [22]. Individual Histelide measures were missing on 4%–6% of the 420 autopsies because of depleted or missing tissue blocks. All available data points were used.

Covariates

Adjusting for covariates helps address the issue of confounding. Covariates were identified using ACT study data and KP Washington electronic health data, with detailed medical record review performed for autopsied participants. For details, see Dublin et al [15]. Briefly, these data sources provided information about age, gender, education, APOE genotype, dementia, treatment for hypertension, and history of comorbid illnesses including diabetes, stroke, and coronary artery disease (which includes myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, coronary angioplasty, or angina). APOE genotyping was performed using standard techniques [23, 24] and dichotomized as any vs. no copies of the APOE Ɛ4 allele.

Statistical analysis

Associations between categorical medication exposure levels and continuous Histelide outcome measures were modeled using a generalized linear model with a Poisson distribution and a log link; model parameters were estimated using generalized estimating equations to account for misspecification of the mean-variance relationship. Such an approach in this context allows for estimation of the ratio of the mean Histelide concentrations among participants at one medication exposure level to the mean Histelide concentrations among participants at another exposure level (the referent group). A separate model was estimated for each of the six outcome measures of interest: Aβ42 and Phospho-τ in the frontal, temporal, and parietal regions. Primary models included adjustment for ACT study cohort (original vs. expansion or replacement), age at death, gender, education (at least some college vs. high school or less), treated hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and coronary artery disease. NSAID and opioid exposure levels were included in the model simultaneously, and thus presented estimates for one medication exposure are adjusted for the other medication.

Additionally, models incorporated inverse-probability weighting to account for selection into the autopsy sample from the broader ACT cohort. This weighting attempts to make the estimated associations of interest more generalizable by accounting for possible selection bias that could be induced by factors influencing who is observed in the autopsy sample—for instance, characteristics of participants that influenced the risk of death or the likelihood of consenting to autopsy. These weights were derived from a logistic regression model estimating the probability of inclusion in the autopsy sample as a function of: ACT study cohort, age, gender, education, stroke and coronary artery disease, opioid and NSAID exposure, and dementia status. To account for uncertainty in estimation of these weights used in our outcome models, all 95% confidence intervals presented are computed using bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap standard errors [19, 25].

In secondary analyses, NSAID and opioid exposures were modeled using continuous values rather than the categorized versions. For this analysis, the TSDDs of NSAIDs and opioids were included in models using cubic spline terms which allow for a more flexible association between total exposure (using continuous measures rather than categories) and the outcomes. As such, a smooth curve illustrating the estimated mean Histelide concentration across a wide spectrum of medication exposure levels (relative to the mean Histelide concentration among those with 0 TSDDs of exposure) can be generated.

All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and R, version 3.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

As of September 30th, 2012, ACT had enrolled 4,724 people. Of these, 1874 (40%) had died, 478 had undergone brain autopsy, and 420 met our eligibility criteria for analyses. Clinical and other characteristics of the 420 individuals whose donated brains were used in this study are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 420 Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) individuals included in this study.

| Brain Autopsies | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 420 | |

| Age at death, median (25th, 75th) | 89 (84, 93) | |

| Male | 179 | 42.6 |

| At least some college | 275 | 65.5 |

| Treated for hypertension | 287 | 68.3 |

| Diabetes | 64 | 15.2 |

| Stroke | 107 | 25.5 |

| Coronary heart disease | 148 | 35.2 |

| APOE ε4 allele | 115 | 30.0 |

| Missing | 37 | 8.8 |

| TSDDs of NSAIDs | ||

| 0 – 60 | 222 | 52.9 |

| 61 – 540 | 135 | 32.1 |

| 541+ | 63 | 15.0 |

| TSDDs of opioids | ||

| 0 – 10 | 184 | 43.8 |

| 11 – 90 | 177 | 42.1 |

| 91+ | 59 | 14.0 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 7 | 1.7 |

| Dementia (DSM IV diagnosis) | 185 | 44.0 |

| AD Type | 110 | 59.5 |

| Vascular | 25 | 13.5 |

| Multiple Etiologies | 33 | 17.8 |

| Other | 17 | 9.2 |

Column percentages are based on non-missing information. The only variable with missing information was APOE ε4 status (missing for N=37). Stroke, coronary heart disease, and diabetes information were based on medical record review of the 10 years during which NSAID and opioid medication exposures were assessed. Hypertension was defined as present if an individual had at least 2 fills of an antihypertensive medication within a 1 year window any time during the 10 years during which NSAID and opioid medication exposures were assessed. Parkinson’s disease status was based on self-report as of the last study visit prior to index date.

We quantified Aβ42 by Histelide and observed that high NSAID usage was associated with greater concentration of Aβ42 in the MFG and SMTG but not in the IPL, although there was a similar trend in IPL as in the other two regions of cerebral cortex (Table 2). For example, mean Aβ42 concentration was estimated to be 44% higher (95% CI: 1.05 – 2.09) in the MFG and 39% higher (95% CI: 1.04 – 1.88) in the SMTG for participants with 541+ TSDDs of NSAID exposure relative to those with 0–60 TSDDs of NSAID exposure. In contrast, we did not find evidence of an association between opioid exposure and concentration of Aβ42 in any of the three regions of interest (Table 3). Ratios comparing mean Aβ42 concentration among the highest and lowest opioid exposure groups were 0.76 (95% CI: 0.50 – 1.06), 1.12 (95% CI: 0.77 – 1.57), and 0.82 (95% CI: 0.55 – 1.17), for the MFG, SMTG, and IPL, respectively.

Table 2.

Association between NSAID usage and concentration of Aβ42 and phospho-τ in three different regions of cerebral cortex.

| NSAID Usage | Adjusted Ratio of Means (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Aβ42] | [Phospho-τ] | |||||

| MFG | SMTG | IPL | MFG | SMTG | IPL | |

|

No/Low (n=222) |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

Interme diate (n=135) |

1.27 (0.96, 1.70) |

1.25 (0.97, 1.71) |

1.21 (0.94, 1.66) |

1.03 (0.79, 1.39) | 1.26 (0.88, 1.94) |

0.93 (0.71, 1.24) |

|

High (n=63) |

1.44 (1.05, 2.09) |

1.39 (1.04, 1.88) |

1.29 (0.95, 1.77) |

0.79 (0.57, 1.39) |

1.32 (0.88, 2.02) |

1.00 (0.68, 1.47) |

Abbreviations: Confidence interval (CI), Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), middle frontal gyrus (MFG), superior and middle temporal gyri (SMTG), inferior parietal lobule (IPL), phospho-τ (phospho-tau).

Table 3.

Association between prescription opioid usage and concentration of Aβ42 and phospho-τ in three different regions of cerebral cortex

| Opioid Usage | Adjusted Ratio of Means (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Aβ42] | [phospho-τ] | |||||

| MFG | SMTG | IPL | MFG | SMTG | IPL | |

|

No/Low (n=184) |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

|

Interme diate (n=177) |

1.02 (0.82, 1.29) |

1.17 (0.95, 1.48) |

0.93 (0.74, 1.19) |

1.28 (0.97, 1.68) |

1.11 (0.79, 1.60) |

1.08 (0.82, 1.42) |

|

High (n=59) |

0.76 (0.50, 1.06) |

1.12 (0.77, 1.57) |

0.82 (0.55, 1.17) |

1.52 (1.03, 2.24) |

1.25 (0.83, 1.86) |

1.48 (0.98, 2.19) |

Abbreviations: Confidence interval (CI), Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), middle frontal gyrus (MFG), superior and middle temporal gyri (SMTG), inferior parietal lobule (IPL), phospho-τ (phospho-tau).

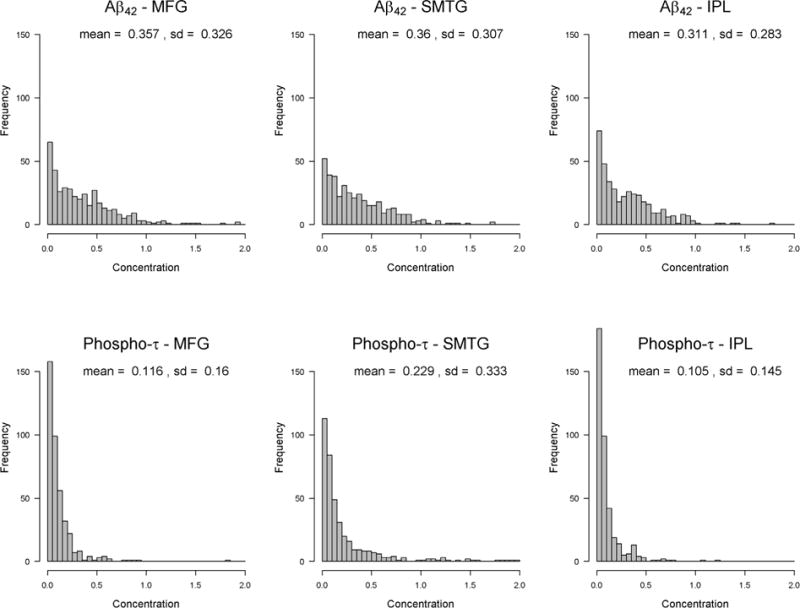

Secondary analyses using continuous rather than categorized NSAID exposure levels also support the conclusion that heavier exposure to NSAIDs (at levels around 540 to 1080 TSDDs) is associated with higher average Aβ42 concentration in the three regions of brain (Figure 1). The solid curves in each plot, which show the adjusted ratio of means comparing mean Aβ42 at a given TSDD exposure level to the mean Aβ42 at no exposure, are significantly greater than 1 in that exposure range (note: the shaded areas on the plots are pointwise 95% CIs). However, we do not estimate significantly elevated mean Aβ42 at the extremely high end of the NSAID exposure spectrum (e.g., >1620 TSDDs), though we recognize data at those levels are more sparse. There was no apparent association between heavier exposure to NSAIDs (at levels around 540 to 1080 TSDDs) and increased phospho-τ concentration in the three regions of brain (Figure 1). The distribution of Histelide measures for Aβ42 and phospho-τ are demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Secondary analysis for Aβ42 and phospho-tau.

Plot of total standardized daily doses (TSDDs) of NSAIDs vs. normalized Histelide concentrations in the three regions of brain: middle frontal gyrus (MFG); superior and middle temporal gyri (SMTG); and inferior parietal lobule (IPL). The solid curve in each plot is the adjusted ratio of means for Aβ42 or phospho-tau at a given TSDDs of NSAID exposure (on the x-axis) to the mean Histelide concentration at 0 TSDDs of exposure, holding other subject covariates constant. The shaded areas on the plots are pointwise 95% CIs.

Figure 2. Distribution of Histelide concentrations for Aβ42 and phospho-tau.

Abbreviations: middle frontal gyrus (MFG), superior and middle temporal gyrus (SMTG), inferior parietal lobule (IPL).

Analyses of concentration of phospho-τ suggested different relationships than were observed for Aβ42. Relative to those with no/low opioid exposure, participants with high opioid exposure had greater phospho-τ concentration in the MFG (adjusted ratio of means = 1.52 with 95% CI = 1.03, 2.24), and a similarly elevated (albeit non-significant) phospho-τ concentration in the IPL (ratio = 1.48 with 95% CI = 0.98, 2.19) (Table 3). NSAID exposure, however, was not associated with increased phospho-τ concentration in any of the regions (Table 2). Ratios comparing mean phospho-τ concentration among the highest and lowest NSAID exposure groups were 0.79 (95% CI: 0.57 – 1.13), 1.32 (95% CI: 0.88 – 2.02), and 1.00 (95% CI: 0.68 – 1.47), for the MFG, SMTG, and IPL, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In 2009, ACT investigators reported that high prescription NSAID usage is associated with higher risk for clinical diagnosis of AD (HR 1.55 with 95% confidence interval = 1.07 to 2.24) using data from 2095 ACT participants [7]. The next year they also observed that high NSAID usage is associated with high NP score (RR 2.16; 95% CI, 1.02–4.25) but not other features of brain aging, including Braak stage of neurofibrillary degeneration [13]. More recently, these investigators showed that increased opioid exposure is not associated with greater neuropathologic changes, but that heavy NSAID use is associated with greater risk of high NP score [15]. To our knowledge, these studies are the first molecular quantification of the intriguing association between protracted NSAID usage and AD. Adequate sample for analysis of less common neuropathologic conditions, such as isolated tauopathy or synucleinopathy, will require assembly of cases from research cohorts rather than from a population-based cohort.

In MFG and SMTG, greater Aβ42 concentration was significantly associated with high NSAID usage. The IPL showed a similar pattern but did not attain statistical significance, suggesting the possibility that the impact of NSAIDs on Aβ42 may vary by region. These findings were further supported by secondary analyses using continuous measures of medication exposure. Opioid usage was not significantly associated with increased Aβ42 concentration in any region. The concordance between our current findings for Aβ42 concentration and previous findings for NP score are validating since one outcome ranks the amount of NPs and the other quantifies the concentration of a major molecular component of NPs [15]. Interestingly, high NSAID usage was not associated with phospho-τ concentration in any of the three cerebral cortical regions, suggesting that the pharmacodynamics effects of NSAIDs may be relatively specific to pathophysiologic processes that lead to increased Aβ peptide accumulation in cerebral cortex. Because of the existing epidemiologic literature on NSAIDs and AD, we focused on hallmark molecular pathologic changes of AD. Future investigations can expand to include Histelide measurement of other molecular pathologic changes that occur commonly in brain of older individuals. In contrast to our more consistent data for high NSAID usage and increased cerebral cortical Aβ peptide levels, our findings for opioid usage have been mixed. Although not associated with Aβ42 concentration, we observed that high opioid usage was significantly associated with greater phospho-τ concentration in the MFG only. Yet our previous work demonstrates that high opioid exposure is not associated with greater Braak stagins for neurofibrillary degeneration: the proportion of people with Braak stage V or VI is similar among people with the heaviest level of opioid use and those with little to no opioid use (32% vs. 29%, adjusted relative risk 0.97 [95% confidence interval 0.49–1.78)]) [15]. Phospho-τ is a component of neuritic processes in NPs, but also of the more abundant NFTs and neuropil threads of neurofibrillary degeneration [26]; all of these structural forms of phospho-τ are quantified by the assay used here. One possible explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that Braak staging is based largely on the distribution of NFTs in brain, not their density in cerebral cortex. Another possibility is that opioids may influence only a subset of phospho-τ containing structures, such as those in neuritic processes. We speculate that the limited association between opioid exposure and MFG concentration of phospho-τ may offer a partial explanation for our previous observation that high opioid use was modestly associated with dementia; however, this should be viewed as preliminary until validated in other neuropathologic or neuroimaging studies.

One concern in pharmaco-epidemiology research is the possibility of confounding by indication. For example, opioids and NSAIDs are prescribed to relieve chronic pain, and it is possible that chronic pain, and not the medications used to treat it, is influencing the neuropathologic changes of AD in brain. The lack of an association between opioid exposure and increased Aβ peptide accumulation in cerebral cortex, as assessed by NP score or Histelide measurement of regional Aβ42 concentration, partially mitigates this concern since the indications for these two classes of medications overlap to a great extent. The same logic applies for our preliminary finding of high opioid usage and MFG phospho-τ concentration; NSAID usage is not associated with phospho-τ concentration in any of the three cerebral cortical regions. Indeed, the apparently distinct relationships between NSAIDs and Aβ42 accumulation and possibly between opioids and regional phospho-τ concentration suggest that different mechanisms of action of these drugs, rather than relief of chronic pain, may underlie the associations with neuropathologic outcomes.

Several studies have shown that exposure of transgenic mice that express mutant human APP to NSAIDs, or to genetic or pharmacologic interventions downstream of COX inhibition [27–29], reduces the cerebral cortical concentration of Aβ peptides, including Aβ42. The relevance of these studies to human exposures is uncertain [7, 9, 11, 30]. Our earlier work using NP score in human tissue appeared to oppose these Aβ studies from transgenic mice, but methodological differences undermined direct comparison. The Aβ42 concentration data from the present study is more directly comparable to methods commonly used in mouse models; amyloid concentration is measured by antibody capture assays in both species. Still, Aβ42 concentration results from human brain in this current study were opposite to the results from our laboratory and others that exposed AD transgenic mice to NSAIDs or other manipulations of the prostaglandin signaling pathway [27–29, 31]. Although there are numerous examples of therapeutics that were effective in transgenic mouse models that ultimately failed to bring therapeutic benefit to patients with AD [9–11, 30], as far as we are aware, these are the first data to indicate that a drug class appeared to have the opposite association with cerebral cortical Aβ42 concentration in the brains of transgenic mice and humans. There are many possible explanations for the apparent opposite relationships between NSAIDs and Aβ42 tissue concentration in humans and in mouse models of AD: the transgenic mice are models of an autosomal dominant form of early onset AD, not the much more common sporadic late onset disease that we have investigated in people; exposure in human subjects is chronic and measured over decades while in model systems exposure occurs on a much shorter time scale; the transgenic mice express mutant human protein in an otherwise mouse background; the transgenic mice drive overexpression of mutant human APP expression using a neuronal promoter; and we know little of the relative differences, if any, in prostaglandin metabolism and signaling in mouse vs. human brain. Regardless of the mechanism, our results suggest caution in extrapolating results from APP transgenic mice to the human condition. An additional possibility to explain this discrepancy seen between mice and human could be confounding. This current study is observational and not experimental, thus it is possible that people who have had NSAID exposure may also have had an array of other exposures (i.e., other pain medications, dietary differences, and amount of physical activity) which could influence neuropathologic changes in the aging brain. The additional exposures in this particular cohort are complex and the limitations of human observational studies need to be recognized.

In summary, for the first time, we showed that high NSAID usage was associated with greater Aβ42 concentration in MFG and SMTG, but not greater phospho-τ concentration in any of the three regions assayed. In contrast, high opioid usage was associated with greater phospho-τ concentration in MFG only and was not associated with Aβ42 concentration in any region. Our consistent findings for high NSAIDs and NPs as well as regional concentration of Aβ42 suggest that high levels of NSAIDs in older individuals regionally promote specific AD pathophysiologic processes, and thus may adversely affect cognitive health.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by grants from the NIH: U01 AG006781, P50 AG005136, P50 AG047366, and the Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowment. We would also like to acknowledge Shannon Rose for technical support and Kathleen Montine for editing assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Kukull WA, Higdon R, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Teri L, Schellenberg GD, van Belle G, Jolley L, Larson EB. Dementia and Alzheimer disease incidence: a prospective cohort study. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:1737–46. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.11.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crane PK, Walker R, Hubbard RA, Li G, Nathan DM, Zheng H, Haneuse S, Craft S, Montine TJ, Kahn SE, McCormick W, McCurry SM, Bowen JD, Larson EB. Glucose levels and risk of dementia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:540–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson EB, Wang L, Bowen JD, McCormick WC, Teri L, Crane P, Kukull W. Exercise is associated with reduced risk for incident dementia among persons 65 years of age and older. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:73–81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-2-200601170-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szekely CA, Thorne JE, Zandi PP, Ek M, Messias E, Breitner JC, Goodman SN. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology. 2004;23:159–69. doi: 10.1159/000078501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart WF, Kawas C, Corrada M, Metter EJ. Risk of Alzheimer’s disease and duration of NSAID use. Neurology. 1997;48:626–32. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J, Tan L, Wang HF, Tan CC, Meng XF, Wang C, Tang SW, Yu JT. Anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of Alzheimer’s disease: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;44:385–96. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breitner JC, Haneuse SJ, Walker R, Dublin S, Crane PK, Gray SL, Larson EB. Risk of dementia and AD with prior exposure to NSAIDs in an elderly community-based cohort. Neurology. 2009;72:1899–905. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a18691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox DR, Hinkley DV. Theoretical Statistics. Chapman & Hall; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aisen PS, Schafer KA, Grundman M, Pfeiffer E, Sano M, Davis KL, Farlow MR, Jin S, Thomas RG, Thal LJ. Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2003;289:2819–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.21.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC, Green RC, Martin BK, Meinert C, Piantadosi S, Sabbagh M. Naproxen and celecoxib do not prevent AD in early results from a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:1800–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260269.93245.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thal LJ, Ferris SH, Kirby L, Block GA, Lines CR, Yuen E, Assaid C, Nessly ML, Norman BA, Baranak CC, Reines SA. A randomized, double-blind, study of rofecoxib in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1204–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, Vogel FS, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Berg L. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–86. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Walker RL, Haneuse S, Crane PK, Gray SL, Breitner JC, Montine TJ. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are associated with increased neuritic plaques. Neurology. 2010;75:1203–10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f52db1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dublin S, Walker RL, Gray SL, Hubbard RA, Anderson ML, Yu O, Crane PK, Larson EB. Prescription Opioids and Risk of Dementia or Cognitive Decline: A Prospective Cohort Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:1519–26. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dublin S, Walker RL, Gray SL, Hubbard RA, Anderson ML, Yu O, Montine TJ, Crane PK, Sonnen JA, Larson EB. Use of Analgesics (Opioids and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) and Dementia-Related Neuropathology in a Community-Based Autopsy Cohort. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58:435–448. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neltner JH, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Denison SK, Anderson S, Patel E, Nelson PT. Digital pathology and image analysis for robust high-throughput quantitative assessment of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:1075–85. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182768de4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong RA. Quantifying the pathology of neurodegenerative disorders: quantitative measurements, sampling strategies and data analysis. Histopathology. 2003;42:521–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2003.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morroni F, Sita G, Tarozzi A, Rimondini R, Hrelia P. Early effects of Abeta1-42 oligomers injection in mice: Involvement of PI3K/Akt/GSK3 and MAPK/ERK1/2 pathways. Behav Brain Res. 2016;314:106–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haneuse S, Schildcrout J, Crane P, Sonnen J, Breitner J, Larson E. Adjustment for selection bias in observational studies with application to the analysis of autopsy data. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32:229–39. doi: 10.1159/000197389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dublin S, Walker RL, Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Weiss NS, Von Korff M, Jackson LA. Use of opioids or benzodiazepines and risk of pneumonia in older adults: a population-based case-control study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1899–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03586.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Postupna N, Rose SE, Bird TD, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Sonnen JA, Larson EB, Keene CD, Montine TJ. Novel antibody capture assay for paraffin-embedded tissue detects wide-ranging amyloid beta and paired helical filament-tau accumulation in cognitively normal older adults. Brain Pathol. 2012;22:472–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postupna N, Keene CD, Crane PK, Gonzalez-Cuyar LF, Sonnen JA, Hewitt J, Rice S, Howard K, Montine KS, Larson EB, Montine TJ. Cerebral cortical Abeta42 and PHF-tau in 325 consecutive brain autopsies stratified by diagnosis, location, and APOE. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74:100–9. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emi M, Wu LL, Robertson MA, Myers RL, Hegele RA, Williams RR, White R, Lalouel JM. Genotyping and sequence analysis of apolipoprotein E isoforms. Genomics. 1988;3:373–9. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(88)90130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:545–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Efron B, T R. An Introduction to the Bootsrap. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi H, Nakazato Y, Kawarabayashi T, Ishiguro K, Ihara Y, Morimatsu M, Hirai S. Extracellular neurofibrillary tangles associated with degenerating neurites and neuropil threads in Alzheimer-type dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;81:603–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00296369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi JK, Jenkins BG, Carreras I, Kaymakcalan S, Cormier K, Kowall NW, Dedeoglu A. Anti-inflammatory treatment in AD mice protects against neuronal pathology. Exp Neurol. 2010;223:377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim GP, Yang F, Chu T, Chen P, Beech W, Teter B, Tran T, Ubeda O, Ashe KH, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Ibuprofen suppresses plaque pathology and inflammation in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5709–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotilinek LA, Westerman MA, Wang Q, Panizzon K, Lim GP, Simonyi A, Lesne S, Falinska A, Younkin LH, Younkin SG, Rowan M, Cleary J, Wallis RA, Sun GY, Cole G, Frautschy S, Anwyl R, Ashe KH. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition improves amyloid-beta-mediated suppression of memory and synaptic plasticity. Brain. 2008;131:651–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breitner JC, Baker LD, Montine TJ, Meinert CL, Lyketsos CG, Ashe KH, Brandt J, Craft S, Evans DE, Green RC, Ismail MS, Martin BK, Mullan MJ, Sabbagh M, Tariot PN. Extended results of the Alzheimer’s disease anti-inflammatory prevention trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:402–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keene CD, Chang RC, Lopez-Yglesias AH, Shalloway BR, Sokal I, Li X, Reed PJ, Keene LM, Montine KS, Breyer RM, Rockhill JK, Montine TJ. Suppressed accumulation of cerebral amyloid {beta} peptides in aged transgenic Alzheimer’s disease mice by transplantation with wild-type or prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 2-null bone marrow. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:346–54. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]