Abstract

Objectives

To compare anatomic results after vaginal uterosacral ligament suspension with absorbable versus permanent suture.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of women who underwent vaginal uterosacral ligament suspension, from 2006 to 2015. We compared two groups: 1) absorbable suspension suture; and 2) permanent suspension suture (even if accompanied by absorbable suture). Our primary outcome was composite anatomic failure defined as: 1) recurrent prolapse in any compartment past the hymen; or 2) retreatment for prolapse. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test and categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to control for confounders. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Of the 242 patients with medium-term follow-up (3 months to 2 years after surgery), 188 underwent vaginal uterosacral ligament suspension with only absorbable suture and 54 underwent suspension with permanent suture. Compared with the absorbable suture cohort, the permanent suture cohort was more likely to have had advanced preoperative prolapse (p=0.01), less likely to have had a prior hysterectomy (p=0.01) and less likely to have undergone a concomitant posterior colporrhaphy/perineoplasty (p<0.01). Overall, there were no differences in composite anatomic failure between the absorbable and permanent suture groups (17.0% v. 20.4%, p=0.41). In multivariable logistic regression analyses, when controlling for covariates, there remained no difference in composite anatomic failure between permanent and absorbable suture groups.

Conclusions

Completion of vaginal uterosacral ligament suspension using only absorbable suture affords similar anatomic outcomes in the medium-term as compared to suspension with additional permanent suture.

Keywords: Prolapse, Uterosacral suspension, Vaginal surgery

Introduction

In the United States, the lifetime risk of undergoing a surgical procedure for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence is 20% by 80 years of age.1 Currently, multiple surgical options exist for treatment of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse (POP). Vaginal uterosacral ligament suspension (USLS) is a common, non-mesh procedure for apical prolapse that was initially described by Shull et al.2 Reported rates of success vary based on definition and length of follow-up, but range from 81.2%–87.1% for the anterior compartment and 89.7%–98.3% for the apical compartment.3,4 It is a well-tolerated procedure with the most common complications being ureteral occlusion and sensory neuropathy with reported rates from large data sets of 1.8% and 6.8%, respectively.3,5,6

The initial description of this procedure involves the utilization of two permanent polyester sutures and one delayed absorbable polydioxanone suture,2 but there have been multiple reiterations of the surgical procedure with interest in balancing risks of complications with a durable repair.4,7–9 Ideally, the procedure would not require permanent material, but it is unclear from the reported literature if the use of permanent suture affords improved surgical outcomes.7–9 Furthermore, if using only absorbable suture, the standard number of sutures is also uncertain, as anywhere from 2 bilaterally to 4 bilaterally have been described.2,7,8

Our institution has longstanding familiarity with use of a single, bilateral absorbable suture along with the use of a mix of permanent and delayed absorbable sutures for vaginal USLS.10 Previous studies have suggested that anatomic failure is not higher in those patients that have undergone suspension without permanent suture.7,8 The objective of this study was to compare anatomic results after vaginal USLS with absorbable versus permanent suture in patients with medium-term surgical follow-up.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study of women who underwent vaginal USLS, for either uterovaginal prolapse or post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse, from 1/2006 to 9/2015, at one academic medical center. After institutional review board approval was obtained, subjects were identified by their current procedural terminology (CPT) code for intraperitoneal colpopexy (57283) using institutional software that queries system-wide diagnosis and procedural codes. All subjects with uteri also underwent concomitant vaginal hysterectomy. Other concomitant transvaginal POP procedures or anti-incontinence surgery with midurethral sling were recorded. Subjects were excluded if they underwent extraperitoneal colpopexy (i.e., sacrospinous colpopexy), uterine hysteropexy, or any laparoscopic prolapse procedures. Our study population included only those with medium-term follow-up, which we considered to be a pelvic exam with POP-Q staging11 between 3 months and 2 years after surgery. During the designated study period, many subjects receiving USLS were also participants in published randomized studies such as the “OPTIMAL”4, “OPUS”12, and “SUPER”13 clinical trials. As such, these participants underwent research study visits with Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POP-Q) exams at regular intervals. We compared two USLS groups: 1) absorbable suture only (any absorbable USLS suture) compared with 2) any permanent suture (any permanent USLS suture, even if accompanied by absorbable USLS suture). Our primary outcome was composite anatomic failure defined as: 1) recurrent prolapse in any compartment beyond the hymen (POP-Q point Ba, Bp, or C >0); or 2) retreatment for prolapse with either surgery or pessary.

We reviewed medical records and collected data regarding demographics, medical and surgical history, concurrent procedures, suture material and number of sutures used for USLS, perioperative complications, POP-Q examinations, and length of follow-up. Perioperative complications were defined as events that occurred within the 12-week postoperative period. All data were extracted via manual chart review and included a detailed review of operative notes as well as postoperative visits up to the last day of follow-up present in our electronic medical record system. Ureteral complication was defined as either 1) transient obstruction of the ureter, relieved with removal of suspension suture or 2) concern for ureteral injury requiring placement of ureteral stents. These were rare complications and therefore combined for analysis. Urinary tract infection (UTI) was recorded if a patient developed symptoms of bacterial cystitis within 12 weeks of surgery. Culture-proven UTIs as well as symptomatic UTIs resulting in empiric treatment without cultures were recorded.

USLS procedures were performed based on the attending surgeon’s preferred technique regarding suture material. Over the course of the study-period, there were six fellowship-trained reconstructive surgeons with a consistent vaginal approach per techniques described in the literature. These techniques use sutures placed in the intermediate uterosacral ligament, at or cephalad to the ischial spine, which are affixed to the vaginal apex, typically considered a “high” uterosacral ligament suspension.2,5 Of the six surgeons’ clinical practice, two always utilized absorbable suture, two always utilized permanent suture and the other two had evolving practice patterns over time. Additionally, over the course of the study-period our academic site participated in the OPTIMAL,4 OPUS12 and SUPER13 trials. Participants in OPTIMAL4 and SUPER13 trials were required to have their USLS performed with one absorbable suture and one permanent suture bilaterally, therefore, surgeon practice pattern may have been altered. Participants enrolled in the OPUS12 trial did not have specific requirements with regards to suture type for suspension.

Data analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.0. Continuous variables were analyzed using the Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate, and categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Bivariate analyses were conducted to determine relationships between variables and risk of failure, followed by multivariable logistic regression to adjust for potential confounders. In the full model, we included known a priori risk factors for prolapse, significantly different baseline characteristics between our two cohorts, and variables that were significant in bivariate analyses. We then conducted a stepwise variable selection procedure to identify the model that best fit the data.

All tests were considered significant at an alpha of 0.05. We used a convenience sample of patients undergoing vaginal USLS during the specified time frame. The medium-term risk of anatomic failure after USLS is reported to be 15–20% in multiple prior studies.3,4 With our sample size, difference in group numbers, and a significance level of 0.05, we had 80% power to detect a two-fold difference in proportions of anatomic failure, assuming a 20% medium-term recurrence risk.14,15

Results

We identified 242 women who underwent USLS during the study period with medium-term follow-up. Most patients were white (86.0%), overweight with an average BMI of 27.4 (SD 5.0), an average age of 62.8 (SD 10.1). Median follow-up was 354.0 days [IQR 225, 416.3]. We defined preoperative advanced prolapse as ≥Stage 3 prolapse in at least one compartment. Of the 238 patients with documented preoperative exams, 151 (62.4%) had advanced prolapse. Regarding the indication for surgery, 198 (81.8%) of patients underwent USLS for uterovaginal prolapse and 44/242 (18.2%) underwent USLS for post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse.

Of the overall study population, 188/242 (77.7%) women underwent USLS with only absorbable suture, and 54/242 (22.3%) underwent USLS with either solely permanent or a combination of permanent and absorbable suture. In the absorbable group, 68/188 (36.2%) received only polyglycolic acid (Polysorb™) suture and 120/188 (63.8%) received only polyglyconate delayed-absorbable (Maxon®) suture. Of the permanent suture group, 46/54 (85.2%) received a combination of polypropylene (Prolene®) and polyglyconate (Maxon®) suture bilaterally, 2/54 (3.7%) had just polypropylene (Prolene®), 5/54 (9.3%) had Gore-Tex®, and 1/54 (1.8%) had polyester (Ethibond®). Importantly, 174/188 (92.6%) of the absorbable group had only 1 USLS suture placed bilaterally. Of the permanent group, 45/54 (83.0%) had 4 total sutures and 9/54 (16.7%) had <4 total sutures.

The most common concomitant procedures were: midurethral sling 35/242 (14.5%), anterior colporrhaphy 188/242 (77.7%) and posterior colporrhaphy/perineoplasty 81/242 (33.5%). In the overall cohort, there were 5 cystotomies (2.1%) either from the prolapse repair or trocar passage during midurethral sling placement. There were 6 patients (2.5%) who had suture removed intraoperatively due to concern for ureteral kinking or ureteral injury and 4/5 (80%) were replaced.

Baseline differences in our two cohorts are summarized in Table 1. Compared with the absorbable suture cohort, the permanent suture cohort was more likely to have had advanced preoperative prolapse (77.8% v. 59.2%, p=0.01), less likely to have had a prior hysterectomy (5.6% v. 21.8%, p=0.01) and less likely to have undergone a concomitant posterior colporrhaphy/perineoplasty (16.7% v. 38.3%, p<0.01). Due to clinical practice in the study period, the absorbable group had a lower median number of sutures placed for USLS (2.0 v. 4.0, p<0.01). Postoperatively, there were no differences between groups in terms of presence of granulation tissue, postoperative UTI, or need for postoperative removal of USLS suture for pain or persistent suture erosion. There were some patients in each group that did not have initial 12-week follow-up which precluded comment on postoperative complications (4/188 2.1% absorbable group v. 1/54 1.9% permanent group). However, these patients had subsequent follow-up in the 3-month to 2-year time frame allowing their inclusion in the primary outcome analysis of composite failure.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Study Groups

| Absorbable Suture (n=188) |

Permanent Suture (n=54) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | |||

| Age (years) | 62.2 ± 10.5 | 64.8 ± 8.1 | 0.10a |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.1 ± 4.9 | 28.5 ± 5.4 | 0.07a |

| Race | 0.91b | ||

| White | 163/187 (87.2%) | 45/53 (84.9%) | |

| African American | 17/187 (9.1%) | 6/53 (11.3%) | |

| Other | 7/187 (3.7%) | 2/53 (3.8%) | |

| Vaginal Deliveries | 2.0 [2.0,3.0] | 2.0 [2.0,3.0] | 0.88b |

| Advanced Prolapsee | 109/184 (59.2%) | 42/54 (77.8%) | 0.01b |

| Prior hysterectomy | 41/188 (21.8%) | 3/54 (5.6%) | <0.01b |

| Diabetes | 14/188 (7.4%) | 10/54 (18.5%) | 0.02b |

| Constipation | 48/188 (25.5%) | 15/54 (27.8%) | 0.74b |

| Smoking Status | 0.25b | ||

| Current Smoker | 11/187 (5.9%) | 1/54 (1.9%) | |

| Past Smoker | 9/187 (4.8%) | 5/54 (9.3%) | |

| Follow-up (days) | 332.5 [218.0,401.0] | 382.0 [349.3, 518.8] | <0.01c |

| Intraoperative | |||

| Hysterectomy | 147/188 (78.2%) | 51/54 (94.4%) | <0.01b |

| Midurethral Sling | 26/188 (13.8%) | 9/54 (16.7%) | 0.60b |

| Anterior Colporrhaphy | 146/188 (77.7%) | 42/54 (77.8%) | 0.99b |

| Posterior Colporrhaphy and/or Perineoplasty | 72/188 (38.3%) | 9/54 (16.7%) | <0.01b |

| Cystotomy | 5/188 (2.7%) | 0/54 (0.0%) | 0.18b |

| Ureteral Kinking/Injury | 4/188 (2.1%) | 2/54 (3.7%) | 0.57b |

| Number of sutures total (End of Case) | 2.0 [2.0, 2.0] | 4.0 [4.0, 4.0] | <0.01c |

| Postoperative Complications | |||

| Granulation Tissue | 5/184 (2.7%) | 3/53 (5.7%) | 0.30d |

| Suture Removal (due to pain) | 6/184 (3.3%) | 5/53 (9.4%) | 0.06d |

| Postop Pain (managed conservatively) | 11/184 (6.0%) | 1/53 (1.9%) | 0.31d |

| UTI | 11/184 (6.0%) | 8/53 (15.1%) | 0.10d |

| Suture Erosion | 0/184 (0%) | 1/53 (1.9%) | 0.22d |

BMI, body mass index; UTI, urinary tract infection

Data are mean ± standard deviation, n (%), or median [interquartile range]

Student’s t-test

Chi-square test

Mann-Whitney U test

Fisher’s exact test

Advanced preoperative prolapse was defined as ≥Stage 3 prolapse in at least one compartment

Composite anatomic failure occurred in 43/188 (17.8%%) of women. There were no differences in composite failure, anatomic failure, compartment of failure, or reoperation between our groups based on suture type (Table 2). However, in bivariate analyses, we identified an increase in composite failure in patients who had advanced preoperative prolapse (21.9% v. 11.5%, p=0.04). In our initial multivariable regression analyses, we included the following covariates in our model: age, BMI, diabetes, preoperative advanced prolapse, prior hysterectomy, concomitant anterior and concomitant posterior colporrhaphy or perineoplasty. After stepwise variable selection, our final model included only the following covariates: preoperative advanced prolapse, prior hysterectomy, concomitant anterior and concomitant posterior colporrhaphy/perineoplasty (Table 3). In our final model, there remained no differences in composite anatomic failure between permanent and absorbable suture groups (Adjusted OR 1.11 with 95% CI 0.49–2.51, p=0.79).

Table 2.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Outcomes at Medium-Term Follow-up

| Absorbable Suture (n=188) | Permanent Suture (n=54) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Failure | 32/188 (17.0%) | 11/54 (20.4%) | 0.57a |

| Prolapse beyond the hymen | |||

| Anterior (POPQ Aa or Ba >0) | 27/185 (14.6%) | 6/53 (11.3%) | 0.54a |

| Posterior (POPQ Ap or Bp >0) | 6/185 (3.2%) | 4/53 (7.5%) | 0.18a |

| Apical (POPQ C >0) | 2/185 (1.1%) | 0/53 (0.0%) | 0.45a |

| Re-treatment for Pelvic Organ Prolapse | 18/188 (9.6%) | 6/54 (11.1%) | 0.76a |

| Surgery | 14/188 (7.4%) | 5/54 (9.3%) | 0.66a |

| Sacrocolpopexy | 8/188 (4.3%) | 2/54 (3.7%) | |

| Anterior or Posterior Colporrhaphy | 3/188 (1.6%) | 2/54 (3.7%) | |

| Colpocleisis | 2/188 (1.1%) | 0/54 (0.0%) | |

| Pessary | 4/188 (2.1%) | 1/54 (1.9%) | 0.90a |

| Most distal point of vaginal segment | |||

| Anterior | −2.0 [−2.8, −0.5] | −1.5 [−2.5, −0.3] | 0.38b |

| Posterior | −3.0 [−3.0, −2.0] | −2.5 [−3.0, −1.8] | 0.0.4b |

| Apical | −7.0 [−8.0, −6.0] | −6.0 [−7.5, −5.0] | 0.02b |

| TVL | 8.0 [7.0, 9.0] | 7.5 [6.8, 8.0] | <0.01b |

POPQ, pelvic organ prolapse quantification, TVL, total vaginal length

Data are n (%), or median [interquartile range]

Chi-square test

Mann-Whitney U test

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model of suture type on composite outcome

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Suture type | ||

| Absorbable | Reference | |

| Permanent | 1.11 (0.49, 2.51) | 0.79 |

| Advanced preoperative prolapse | 2.23 (1.00, 4.95) | 0.04 |

| Anterior Colporrhaphy | 0.59 (0.27, 1.34) | 0.21 |

| Posterior Colporrhaphy | 0.46 (0.20, 1.05) | 0.07 |

| Prior hysterectomy | 2.57 (1.13, 5.82) | 0.02 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

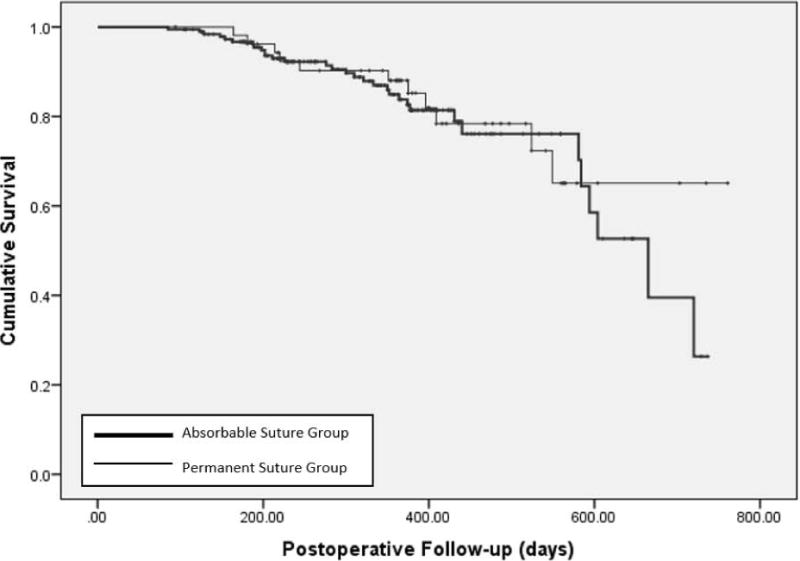

In this same model, advanced preoperative prolapse (Adjusted OR 2.23 with 95% CI 1.01, 4.95, p=0.04) and prior hysterectomy (Adjusted OR 2.57 with 95% CI 1.13–4.95, p=0.02) were associated with increased odds of composite failure. Since 92.6% of the absorbable cohort had a single suspension suture bilaterally, the total number of sutures was highly correlated with suture type with a Spearman’s correlation of 0.78 (p < 0.01) and we did not include suture number as a variable in our model. Given the variable follow-up times between our groups, we performed a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (Fig.1). Based on the log rank test, there were no significant differences in prolapse recurrence between the absorbable and permanent suture groups (P=0.61).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve depicting time to prolapse recurrence after uterosacral ligament suspension. Overall, there was no significant difference between the time to prolapse recurrence in the absorbable and the permanent suture group with p=0.61

Finally, we performed a subset analysis amongst patients in the absorbable cohort. There was a similar amount of composite failures when the suspension was performed with polyglycolic acid (Polysorb™) suture as compared to polyglyconate delayed-absorbable sutures (Maxon®) (10.1% Polysorb v. 21.0% Maxon, p 0.06).

Discussion

In our retrospective cohort study, there were no differences in anatomic outcomes or reoperation in women who underwent vaginal uterosacral ligament suspension with solely absorbable sutures compared with those where permanent sutures were included. In the medium-term, the risk of surgical failure was 17.8% based on our composite anatomic outcome definition. In a multivariable regression analysis, when controlling for potential confounders, absorbable suture was still not significantly associated with increased odds of failure even though >96% of the procedures performed with absorbable suture were also performed with only one suspension suture bilaterally.

The strengths of our study include the large study population with consistent surgical techniques performed over a 9-year study period. Our cohort study also benefits from detailed pre- and peri-operative information. The serial postoperative anatomic data with POP-Q examinations provide objective data for which to develop our composite outcome. We used a rigorous definition of anatomic failure that is supported by the literature as it has been established that symptoms are less likely with prolapse at or above the hymen.16 Lastly, given that a large proportion of study patients had their suspension performed with a single absorbable suspension suture bilaterally, this significantly adds to the literature as this modification has not previously been described. We had a higher incidence of advanced preoperative prolapse and uterovaginal prolapse in the permanent suture group which could lead to limited generalizability of our results. As participants were required to have prolapse past the hymen to be included in OPTIMAL4 or SUPER,13 we propose that this is the driving factor behind the presence of more advanced prolapse in the permanent suture group. Importantly, the choice of suture was either by surgeon practice, or due to the standardized requirements of a clinical trial, and was not influenced by the presence or other patient factors. Regardless, we applied a rigorous multivariable model to our primary outcome to control for these factors.

Our data are limited by our retrospective, single-institution approach. These data could be skewed by follow-up bias toward higher recurrence given that patients who are doing well are not as likely to return for follow-up over the long-term. The median time of follow-up amongst this cohort was slightly less than a year, but as polyglyconate suture and polyglactin suture are completely absorbed by 6 and 2 months respectively,17,18 one would expect an increase in early failures in the absorbable group if they were to occur. There was an apparent drop-off in the absorbable suture group survival curve after 600 days of follow-up, but this is likely due to small numbers of patients with longer follow-up and censoring. Longer-term studies are needed to comment on the longevity of repairs with solely absorbable suture for USLS. Although our cohorts were not balanced in size (e.g. 188 in the absorbable group vs 54 in the permanent group), we were powered to detect a 20% difference in anatomic failure accounting for this difference. Future studies incorporating more patients in the permanent suture arm would allow for increased power to detect a smaller difference in failure between groups. Although we can suggest general satisfaction levels in the postoperative period, we do not have data from standardized postoperative symptom questionnaires, and therefore, another limitation to our data is the lack of rigorous subjective measures from which a true composite outcome could be assessed.

Overall, our specific apical and anterior compartment failures were 0.8% and 13.6%, respectively, which is consistent with the reported rates in the literature of upwards of 4.9% and 22.9%, respectively.3 In our cohort, postoperative complications, including erosion of permanent suture and suture removal for pain, occurred at similar or lower frequency to what is reported in the current literature.19 There is a possibility that we have under-reported these complications if patients sought care elsewhere in their postoperative course, which is a limitation of a retrospective study design. Ureteral occlusion20 and postoperative pain21 are the most common adverse events experienced by women undergoing uterosacral ligament suspension. Although, number of sutures and suture type have not necessarily been correlated with an increased risk of ureteral kinking 19 or pain, our overall lower number of suspension sutures may be a reason for our lower number of complications compared to what is reported in the literature.5

In our logistic regression model, when controlling for other covariates, advanced preoperative prolapse and prior hysterectomy were found to be risk factors for composite anatomic failure. Advanced preoperative prolapse is a well-known risk factor for recurrent prolapse.22,23 Our data suggests that additional counseling may be warranted in regards to postoperative success in women with advanced prolapse and post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse if they are to undergo uterosacral ligament suspension, but this finding would need to be reinforced with prospective data.

Although the “high” uterosacral ligament was initially described using permanent suture,2 use of absorbable suture has been associated with excellent clinical outcomes. Wong et. al describe their case series of USLS using two PDS sutures bilaterally and report a composite failure rate of 7% at a median follow-up rate of 12 months specifically evaluating apical failure.8 Natale et al., described a series of 113 patients who underwent a USLS with one polyglactin suture bilaterally and reported similar apical success rates at one-year follow-up. However, the vast majority of patients in their study also underwent insertion of an anterior polypropylene mesh during surgery so this study does not truly speak to success rates after USLS without permanent material.24 Other retrospective studies have suggested that permanent suture offers better anatomical support as Chung et al., reported an increased rate of prolapse past the hymen in patients undergoing suspension with 2–4 polyglyconate sutures bilaterally as compared to polyester and polydioxanone sutures bilaterally. The mean follow-up time for these patients was less than 6 months and the absolute rates of apical recurrence were very low (1% and 6% respectively).9 Our data adds to the current literature as there is a paucity of studies that describe USLS with a single, bilateral absorbable suspension suture, but comparative studies with randomization of groups and consistent, long-term surgical follow-up are needed.

In conclusion, in this cohort, completion of vaginal uterosacral ligament suspension using absorbable suture, even when a single suspension suture is placed bilaterally, affords similar anatomic outcomes in the medium-term as compared to vaginal USLS with additional permanent suture.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: Dr. Siddiqui has protected research time that is supported by award number K12-DK100024 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Dr. Siddiqui has received grant funding from Medtronic Inc, but neither of these resources provided support for this study. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Megan S. BRADLEY, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Jennifer A. BICKHAUS, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Cindy L. AMUNDSEN, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Laura K. NEWCOMB, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Tracy TRUONG, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Alison C. WEIDNER, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

Nazema Y. SIDDIQUI, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC.

References

- 1.Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, et al. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun;123(6):1201–1206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, et al. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Dec;183(6):1365–1373. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.110910. discussion 1373–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Margulies RU, Rogers MA, Morgan DM. Outcomes of transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb;202(2):124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse: the OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014 Mar 12;311(10):1023–1034. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barber MD, Visco AG, Weidner AC, et al. Bilateral uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension with site-specific endopelvic fascia defect repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Dec;183(6):1402–1410. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.111298. discussion 1410–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flynn MK, Weidner AC, Amundsen CL. Sensory nerve injury after uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Dec;195(6):1869–1872. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasturi S, Bentley-Taylor M, Woodman PJ, et al. High uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension: comparison of absorbable vs. permanent suture for apical fixation. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Jul;23(7):941–945. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong MJ, Rezvan A, Bhatia NN, et al. Uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension using delayed absorbable monofilament suture. Int Urogynecol J. 2011 Nov;22(11):1389–1394. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1470-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung CP, Miskimins R, Kuehl TJ, et al. Permanent suture used in uterosacral ligament suspension offers better anatomical support than delayed absorbable suture. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Feb;23(2):223–227. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1556-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amundsen CL, Flynn BJ, Webster GD. Anatomical correction of vaginal vault prolapse by uterosacral ligament fixation in women who also require a pubovaginal sling. J Urol. 2003 May;169(5):1770–1774. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000061472.94183.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Jul;175(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei JT, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al. A midurethral sling to reduce incontinence after vaginal prolapse repair. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jun 21;366(25):2358–2367. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1111967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nager CW, Zyczynski H, Rogers RG, et al. The Design of a Randomized Trial of Vaginal Surgery for Uterovaginal Prolapse: Vaginal Hysterectomy With Native Tissue Vault Suspension Versus Mesh Hysteropexy Suspension (The Study of Uterine Prolapse Procedures Randomized Trial) Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2016 Apr 6; doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva WA, Pauls RN, Segal JL, et al. Uterosacral ligament vault suspension: five-year outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Aug;108(2):255–263. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000224610.83158.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edenfield AL, Amundsen CL, Weidner AC, et al. Vaginal prolapse recurrence after uterosacral ligament suspension in normal-weight compared with overweight and obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Mar;121(3):554–559. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182839eeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barber MD, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al. Defining success after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Sep;114(3):600–609. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b2b1ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molea G, Schonauer F, Bifulco G, et al. Comparative study on biocompatibility and absorption times of three absorbable monofilament suture materials (Polydioxanone, Poliglecaprone 25, Glycomer 631) Br J Plast Surg. 2000 Mar;53(2):137–141. doi: 10.1054/bjps.1999.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salthouse TN, Matlaga BF. Polyglactin 910 suture absorption and the role of cellular enzymes. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1976 Apr;142(4):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Unger CA, Walters MD, Ridgeway B, et al. Incidence of adverse events after uterosacral colpopexy for uterovaginal and posthysterectomy vault prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 May;212(5):603.e601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson E, Bilbao JA, Vera RW, et al. Risk factors for ureteral occlusion during transvaginal uterosacral ligament suspension. Int Urogynecol J. 2015 Dec;26(12):1809–1814. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2770-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montoya TI, Luebbehusen HI, Schaffer JI, et al. Sensory neuropathy following suspension of the vaginal apex to the proximal uterosacral ligaments. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 Dec;23(12):1735–1740. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vergeldt TF, Weemhoff M, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse and its recurrence: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2015 Nov;26(11):1559–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00192-015-2695-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whiteside JL, Weber AM, Meyn LA, et al. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Nov;191(5):1533–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Natale F, La Penna C, Padoa A, et al. High levator myorraphy versus uterosacral ligament suspension for vaginal vault fixation: a prospective, randomized study. Int Urogynecol J. 2010 May;21(5):515–522. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]