Abstract

The Rhynie cherts Unit is a 407 million-year old geological site in Scotland that preserves the most ancient known land plant ecosystem, including associated animals, fungi, algae and bacteria. The quality of preservation is astonishing, and the initial description of several plants 100 years ago had a huge impact on botany. Subsequent discoveries provided unparalleled insights into early life on land. These include the earliest records of plant life cycles and fungal symbioses, the nature of soil microorganisms and the diversity of arthropods. Today the Rhynie chert (here including the Rhynie and Windyfield cherts) takes on new relevance, especially in relation to advances in the fields of developmental genetics and Earth systems science. New methods and analytical techniques also contribute to a better understanding of the environment and its organisms. Key discoveries are reviewed, focusing on the geology of the site, the organisms and the palaeoenvironments. The plants and their symbionts are of particular relevance to understanding the early evolution of the plant life cycle and the origins of fundamental organs and tissue systems. The Rhynie chert provides remarkable insights into the structure and interactions of early terrestrial communities, and it has a significant role to play in developing our understanding of their broader impact on Earth systems.

This article is part of a discussion meeting issue ‘The Rhynie cherts: our earliest terrestrial ecosystem revisited’.

Keywords: fossil, evolution, plant, animal, development, genetics

1. Introduction

This issue is based on a Discussion Meeting held at the Royal Society in March 2017 to celebrate the centenary of the first of five major publications on a 407-million year old terrestrial ecosystem that was exceptionally preserved by silica in cherts originating as sinter around ancient hot springs [1–5]. Its aims were to integrate old and new information on the biota, including plants, animals, bacteria and fungi, in order to explore how these early mainly terrestrial organisms interacted with each other and the environment and, in the case of the plants, to integrate recent advances in developmental genetics to inform on the early evolution of tissues and organ systems.

2. Geology of the Rhynie locality

The cherts occur as lenses in a succession of shales and sandstones (Dryden Flags Formation) located in the Rhynie Basin, near the eponymous village, some 50 km northeast of Aberdeen [6]. Palaeogeographically they were located in an inland intermontane basin on the Devonian Old Red Sandstone Continent, which at that time was situated about 28° south of the equator. The age of the deposit was uncertain but originally considered no younger than the Middle Old Red Sandstone (=Middle Devonian). Subsequent analyses of spore assemblages in the intervening shales showed that they were older, belonging to the Lower Devonian (middle Pragian to lower Emsian stages) [7,8]. More recently, radiometric measurements produced similar ages. 40Ar/39Ar from vein-hosted hydrothermal K-feldspar and hydrothermally altered andesite gave 407.6 ± 2.2 Ma [9], whereas 206Pb/238U zircon from the Milton of Noth Andesite gave 411.5 ± 1.3 Ma [10]. Differences in methodology, potential sources of error and underpinning geological assumptions account for these differences. For example, the Milton of Noth Andesite sits stratigraphically below the Rhynie chert, and the link between its emplacement and the hydrothermal activity that formed the cherts is not proven [9]. The radiometric date might, therefore, reflect the inception of volcanic activity preceding deposition of the cherts. We favour the age of 407.6 ± 2.2 Ma, which is more consistent with the chronostratic interval given by the spore assemblage biozone [8] and the corresponding numerical ages for stage boundaries in The geologic time scale, 2012 [11].

3. The beginnings of research on the Rhynie chert

The initial discovery of the chert and the recognition that it preserved both plants (tracheophytes subsequently named Rhynia and Asteroxylon) and animals (the crustacean, Lepidocaris) were made by William Mackie [12], a general practitioner in Elgin, Moray, Aberdeenshire and very proficient geologist. In 1912, he collected materials as loose blocks in walls and fields near Rhynie, the deposit itself being subsurface. Its location was subsequently trenched by a Mr Tait, who was a fossil collector at the Geological Survey, with financial assistance from the British Association and the Royal Society [13]. The excavated blocks were then cut and petrographic thin sections made by a professional geological preparator (Hemingway) for examination by two Royal Society fellows, Robert Kidston and William H. Lang. Kidston originally intended collaboration with David Gwynne-Vaughan, who died prematurely in 1915. Their results were published in five papers in the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh [1–5], the first in 1917, and these had considerable impact on the wider botanical community. Indeed Scott [14] added a final chapter to the first volume of the third edition of his Studies in Fossil Botany to accommodate them. Prior to these discoveries, the most extensive records of early tracheophytes came from Lower Devonian sediments (Emsian Stage) in Canada and centred on the Psilophyton complex, which encompassed curious leafless plants with smooth or spiny axes bearing distinctive terminal clusters of fusiform sporangia [15]. These were preserved as thin films of carbon with little or no internal anatomy and certainly no spores. Appreciating similarities in gross anatomy and differences in their simplicity from other groups of vascular cryptograms, Kidston & Lang erected the ‘class’ Psilophytales, for plants with terminal sporangia with ‘no relationship to leaves or leaf-like organs' [1]. While commenting on similarities with living Psilotum in the Psilotales, which also lacks leaves and roots, they stated there was no ‘direct line of descent’—a conclusion that presaged contemporary views that the morphology of Psilotum is highly reduced and that it is related to ferns [16–18].

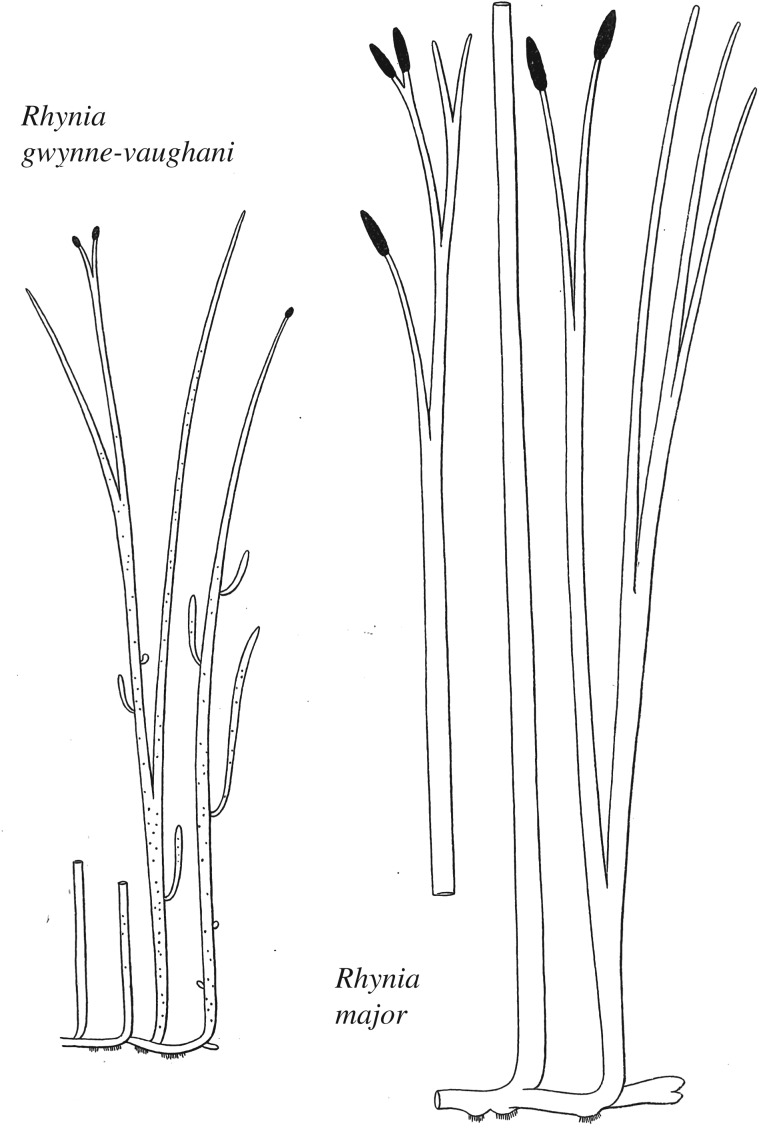

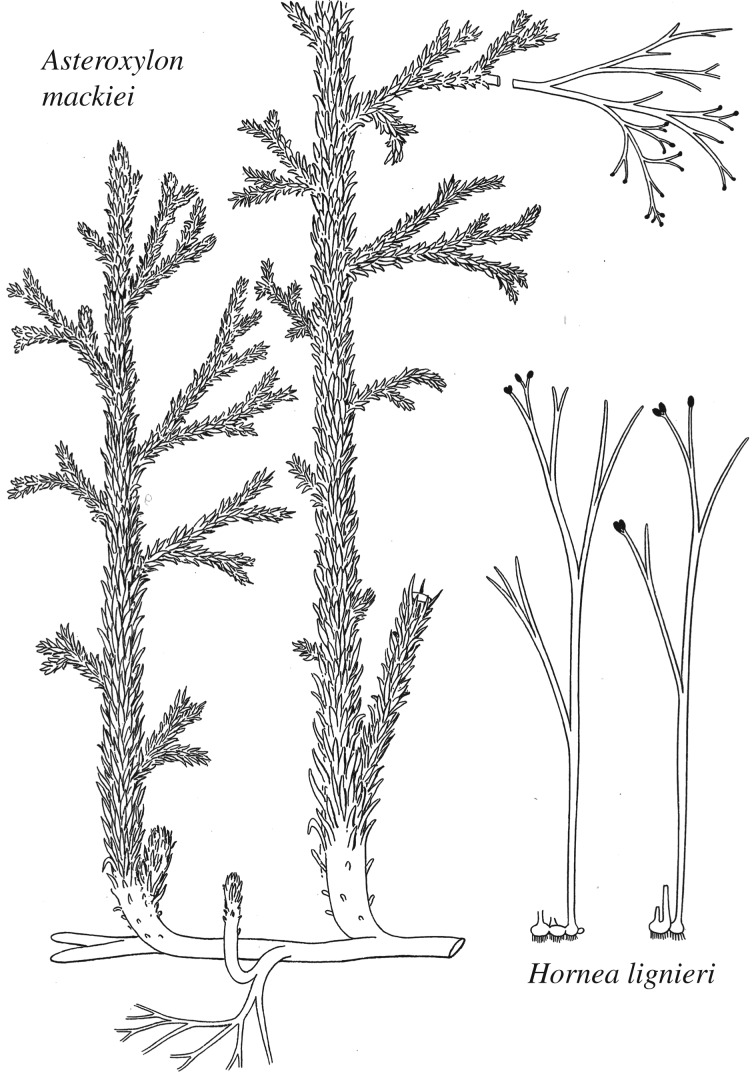

The first three papers contain beautifully illustrated accounts of four plants with primitive vascular systems viz. Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii, Rhynia major (now Aglaophyton majus) [19] (figure 1), Hornea lignieri (now Horneophyton lignieri) and Asteroxylon mackiei (figure 2). After investigating the upright stems, horizontal rhizomes with rhizoids and elongate terminal sporangia of R. gwynne-vaughanii, Kidston and Lang commented that their descriptions were ‘almost as well as if we were dealing with an existing species'. Such is the preservation of anatomy in the chert plants [20], which also enables us to infer how key tissue systems might have functioned (e.g. of stomata [21] and vascular tissues [22]). Discussion in Kidston and Lang's papers included considerations on the affinities of the plants, and it also touched on their wider relevance to such issues as the alternation of generations [23] and the evolution of shoots, roots and leaves, which are issues that have resonance today following resurrection of interest in lower plants stimulated by the development of the moss model organism, Physcomitrella patens, [24,25] and widespread genome sequencing of key taxa including the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha [26] and lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii [27]. These are beginning to shed light on the evolution of body plans including roots [28] and shoots [29] and stem cells [30], thus providing greater understanding of the innovations involved in the evolution of tracheophytes as they colonized the land. Such insights cannot be extended to the early history of bryophytes. Arguably the greatest enigma of the Rhynie chert ecosystem is the complete absence of these basal embryophytes that today include the liverworts, hornworts and mosses.

Figure 1.

Kidston and Lang's original reconstructions of Rhynie gwynne-vaughanii and Aglaophyton majus (Rhynia major) [4].

Figure 2.

Kidston and Lang's original reconstructions of Asteroxylon mackiei and Horneophyton lignieri (Hornea lignieri) [4].

In their final paper, Kidston & Lang [5] described six species of fungi based mainly on spores/cysts and hyphae. They concluded that most of these were saprophytes, but they did not exclude the possibility that some were mycorrhizal. The presence of mycorrhizal fungi is now confirmed, and there are many reports describing symbioses in the chert [31]. Kidston and Lang also described eubacteria, cyanobacteria, a characean alga and the enigmatic genus, Prototaxites [32]. They mentioned animals (crustaceans) only in passing, although arthropods had been recognized by Mackie in 1913 [12]. The first description of the trigonotarbids (extinct arachnids) [33] was soon followed by the first mite and arguably the first insect, the spring-tail Rhyniella [34]. Aquatic arthropods such as the crustacean Lepidocaris were also described [35]. More recent findings on both aquatic and terrestrial arthropods, including the earliest nematode [36], are evaluated here [37,38].

4. The Lyon era

A renaissance in palaeobotanical activity followed the purchase of the Rhynie chert site by Dr Alexander Geoffrey Lyon, a native of Aberdeen and an academic at Cardiff University. Hundreds of match boxes containing chips of chert are still housed in the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. These are testament to his modus operandi of sifting through semi-transparent flakes for fragments of plants and animals. He employed a local monumental mason to cut large slabs of chert until the firm appreciated that the costs of damage to their saw blades greatly exceeded Dr Lyon's payments. This resulted in his purchasing a machine for cutting thin sections. These were supplemented by numerous cellulose acetate peels, which also allow the cellular detail of structures to be imaged on a microscope. Many are now housed at Aberdeen University as part of the Lyon Bequest. His major contribution was undoubtedly the discovery of the sporangia of Asteroxylon mackiei [39], which confirmed its affinity with lycopods. Originally, Kidston & Lang [3] cautiously proposed that leafless, bifurcating axes with terminal sporangia found associated with A. mackiei were its reproductive organs (figure 2). These were later shown by Lyon to be a separate species that he named Nothia aphylla, which is now one of the most extensively studied plants in the chert being known from its anatomy, growth form and autecology [40]. Lyon's most notable contribution to the fauna was his discovery of book-lungs in the trigonotarbid arachnid, Palaeocharinus, which confirmed the terrestrial habitat of this animal [41].

In 1964, Lyon opened two trenches to introduce the locality to members of an excursion associated with the International Botanical Congress in Edinburgh and to provide ‘souvenirs’ from the site [13]. His generosity was somewhat overshadowed by the overnight theft of large quantities of chert just prior to the excursion. The perpetrators were never caught. Further evidence for his generosity came from his gifts of chert to interested parties, most particularly to Professor Winfried Remy at Münster (see below), and readily allowing access to the fields, subject to agreements with local farmers and the safety of both people and livestock!

In Wales, of the three research students (Akhlaq Ahmed Bhutta, Wagih El-S. El-Saadawy and David Edwards) who worked on the chert, Edwards' work is of particular significance as it drew attention to the fact that the xylem cells of Rhynia major lacked wall thickenings, something that had already been noted by Kidston and Lang. This is a key difference from modern tracheophytes and its sister species Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii. He therefore transferred it to a new genus Aglaophyton. The Greek roots of the name mean beauty, and it also incorporates Geoffrey Lyon's initials [42]. His further investigation of R. gwynne-vaughanii revealed the complexity of its growth habit, including abscission of sporangia [43].

5. Recent research from the University of Münster and Aberdeen University

Lyon himself continued his work on the chert following his retirement to the Old Manse in Rhynie. In 1992, he gifted the site to Scottish Natural Heritage, the national conservation organization, with the proviso that it remained under agricultural use and that they would continue to support scientific research [13]. By the late seventies, Professor Winfried Remy and his family had accumulated a large quantity of material that was studied at Münster and produced the most sensational discoveries since those in the original papers by Kidston and Lang. These included tracheophyte gametophytes with well-preserved gametangia and even preservation of the liberation of antherozoids [44,45]. This research is now led by Professor Hans Kerp [20]. Their approach has been simple, time consuming, but very effective: literally thousands of thin translucent sections of rock were produced by systematic sectioning of the chert by team member Hagen Hass. These sections could then be imaged using transmitted light microscopy. Thick sections proved to be far more informative than cellulose acetate peels. This work resulted in additional data on the plants, new animals [37,38] and algae, and it opened up the field of palaeomycology. Study of the fungi was revived under the leadership of the late Professor Thomas Norwood Taylor (Kansas University), initially in collaboration with Remy, and continues today in Munich [46] and London [23,31]. Discoveries have included recognition of mycorrhiza, initially as arbuscules in Aglaophyton [47], an ascomycote perithecium in Asteroxylon [48] and a cyanolichen [49] as well as examples of parasitism (e.g. in the charophycean alga Palaeonitella) [50] and saprotrophy [51]. It had long been postulated by Pirozynski and Malloch that associations of fungi and algae were essential to the colonization of the land [52] and here in the chert was the first direct evidence in the form of mycorrhizae-like associations in the tracheophytes involving Glomeromycota [47] and, more recently, Mucoromycota [53]. Further support for this hypothesis is provided by recent progress in identifying symbiotic fungi in extant hepatic thalli, a group closely related to the earliest embryophytes [54]. While much is now written about the ability of the earliest land plants to draw down CO2 from the atmosphere via chemical rock weathering, resulting in climate change on a global scale [55–58], it is now increasingly apparent that fungal/plant associations had the potential for even greater impact [59].

Certain cherts are a surface-expression of heavy metal hydrothermal systems and as such are associated with goldmining. Analyses of those in the Rhynie area showed that they were no exception, being enriched in arsenic, anatomy and gold, but fortunately for palaeontological research, drilling by an exploration company in the vicinity of the Rhynie chert locality found insufficient quantities for commercial exploitation [60]. Subsequent drilling by the Aberdeen University Geology Department in 1988 produced the first core through the chert-bearing sequence itself and studies of this and subsequent cores have led to a burgeoning of geological and palaeontological activity. These cores allowed the description of plant succession series through 35 m of core containing more than 50 thin chert horizons [61,62], and they also led to the discovery of new animals. The latter inter alia included a further arachnid, the harvestman, Eophalangium sheari [63], which, in contrast with the book-lungs of trigonotarbids, possessed tracheal tubes, a myriapod (Eoarthropleura) [64] and new crustacean (Castrocollis wilsonae) [65]. These new explorations were led by Professor Nigel Trewin at Aberdeen University, who was responsible not only for inspiring renewed interest in the chert in the UK but also for the discovery of a second fossiliferous ‘outcrop’ at nearby Windyfield farm—the Windyfield chert [13]. This has yielded a second zosterophyll (Ventarura) [66]; the first, Trichopherophyton, was described by Lyon and Edwards [67], as well as a number of new arthropods [64]. These included the hexapod Leverhulmia, possibly the earliest known apterous insect [68], a centipede (scuterigomorph Crussolum sp.) [69], a trigonotarbid Palaeocharinus tuberculatus [70], a new univalve crustacean Ebullitiocaris oviformis [71] and encrustacean Nauplius larvae [72]. Together, the Rhynie and Winderfield cherts contain the most diverse assemblage of freshwater and terrestrial animals of their age in the world and a record number of earliest occurrences, including mites, harvestmen, insects, springtails and nematodes.

Dr Lyon died in 1999 and subsequent research at Aberdeen was partly funded by The Lyon Bequest to Aberdeen University. He also left most of his extensive collection of peels and slides to the university. Thanks to such beneficence, five PhD students have graduated, while Trewin and co-workers have visited New Zealand and Yellowstone National Park, USA, to examine processes and deposits in active equivalents of hot springs and to study taphonomic aspects of the biota [73,74]. The latter has been complemented by observations and experimental approaches in Cardiff by Channing [75], who has been tracing the nature of hot springs biota through time [76,77]. Studies of the cores at Aberdeen have allowed insights into the nature of the complete chert-bearing sequence including the sedimentary rocks between the chert beds that contain abundant dispersed spores [78]. Detailed analysis of the biota from numerous chert bands informs on plant habitats, succession and substrates [61], which can then be compared with modern hot spring systems. Kidston & Lang [5] had named the aggregations of organic matter as peats in their final paper, although they recognized that they differed from the definition of extant peats in that there was little evidence of homogenization. They are thus better recognized as accumulation of decaying plants over a limited time interval due to the fluctuating nature of the hot spring system, with little mineral/sediment input and little bioturbation (no earthworms, but collembolans have a potentially similar role) that provided substrates for further plant colonization.

6. Future directions

This historical review of research on the Rhynie chert set the scene for the Discussion Meeting that brought together palaeontologists, neobiologists and physical scientists with the aim of exploring the possibilities of more integrated approaches. A round-table discussion at the end of the meeting identified five areas that hold particular future promise.

1. Rapid advances in the fields of developmental genetics and functional biology are shedding light on the evolution of plant form and function. The molecular mechanisms regulating development of roots, shoots, vascular system, stomates, apical meristems and leaves are revealing surprisingly deep seated similarity for core organs and tissues across plants. Fossils from the Rhynie chert provide additional extinct phenotypes with which to test some of the new ideas of how development is regulated in plants. Also, theories of plant development arising from the study of model organisms need to be consistent with these distinctive early fossils. Furthermore, plant developmental genetics raises specific questions about the nature of core systems such as roots, meristems and life cycles that could in part be addressed through further study of plants preserved in this fossil system.

2. Organism associations are now known to be highly diverse in the Rhynie chert and include several forms of mycorrhizal-like symbiosis. It is becoming clear that symbiotic associations with fungi were important to the colonization of the land by plants as well as by lichen-like associations. Recent discoveries demonstrate that there is a greater diversity of mycorrhizal fungi in living bryophytes and pteridophytes than previously recognized. Further comparative study of these living groups and related fossils is needed to shed light on how the symbioses evolved.

3. To what extent was the Rhynie chert representative of the broader environment of the time? Research on modern geothermal analogues suggests that the plants may have been under various forms of environmental stress (e.g. salinity, heavy metals) and the vegetation may be specialized to the environment of sinter surfaces. However, spores dispersed in associated sediments indicate that some elements of the Rhynie chert flora could have been more cosmopolitan and, therefore, not restricted to sinter system soils. The extent to which the plants preserved in the chert represent a specialized flora needs further evaluation in the context of the chemistry of soil substrate and water. Also present in the environment were organisms that have no real analogues in the modern world. The most striking of these was the giant fungus Prototaxites, shown here for the first time to be an ascomycete [32].

4. Methods of imaging the Rhynie chert fossils still rely mainly on white light microscopy. Confocal laser scanning microscopy is now being successfully employed on the microorganism component [79]. Developments in processing optical software and image stacks in particular to create better-focused images and three-dimensional representations are beginning to enable a new level of exploration of these exquisitely preserved fossil microorganisms and arthropods. Combing advances in imaging technology with new geochemical methods promises highly targeted analyses of the organic remains of cells and their constituent elements [80]. Also, computer animation helps to bring extinct arthropods to life.

5. The impact of the evolution of plants and their symbiotic fungi on the broader Earth system including atmospheric greenhouse gas composition and climate is an area of great interest. Even communities dominated by bryophytes and lichens today are known to play significant roles in net primary productivity and nitrogen fixation. Further basic investigation is needed of the effects of lichens, liverworts, hornworts and herbaceous lycopods on rock weathering. Because of differences in atmospheric composition in the Palaeozoic Era, the influence of carbon dioxide fertilization on these early symbiotic associations needs evaluation.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the late Nigel Trewin for his insights into the palaeoenvironment and for reading and commenting on the manuscript.

Endnote

We correct spelling of the specific epithet of Aglaophyton here and throughout the volume from major to majus in accordance with article 23.5 of the ICN (Melboure Code).

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed conceptually to the scope of the Discussion Meeting and to the content of this article. Conclusions reflect main points drawn out during course of meeting. D.E. drafted the manuscript. P.K. and L.D. contributed to further drafts and to critical discussion.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by European Union FP7: PLANT developmental biology: discovering the ORIGINS of form—ITN to L.D. and P.K. European Research Council Advanced Grant EVO500 (project number 25028) to L.D. D.E. received support from the Gatsby Charitable Foundation and the Leverhulme Trust.

References

- 1.Kidston R, Lang WH. 1917. On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part I. Rhynia gwynne-vaughani Kidston and Lang. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 51, 761–784. ( 10.1017/S0080456800008991) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidston R, Lang WH. 1920. On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part II. Additional notes on Rhynia gwynne-vaughani, Kidston and Lang; with descriptions of Rhynia major, n. sp., and Hornea lignieri, n. g., n. sp. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 52, 603–627. ( 10.1017/S0080456800004488) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidston R, Lang WH. 1920. On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part III. Asteroxylon mackiei, Kidston and Lang. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 52, 643–680. ( 10.1017/S0080456800004506) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidston R, Lang WH. 1921. On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part IV. Restorations of the vascular cryptogams, and discussion on their bearing on the general morphology of the pteridophyta and the origin of the organization of land-plants. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 52, 831–854. ( 10.1017/S0080456800016033) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kidston R, Lang WH. 1921. On Old Red Sandstone plants showing structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part V. The Thallophyta occurring in the Peat-Bed; the succession of the plants throughout a vertical section of the bed, and the conditions of accumulation and preservation of the deposit. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 52, 855–902. ( 10.1017/S0080456800016045) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rice CM, Ashcroft WA. 2004. The geology of the northern half of the Rhynie Basin, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 299–308. ( 10.1017/S0263593300000705) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson JB. 1967. Some British Lower Devonian spore assemblages and their stratigraphic significance. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 1, 111–129. ( 10.1016/0034-6667(67)90114-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wellman CH. 2006. Spore assemblages from the Lower Devonian ‘Lower Old Red Sandstone’ deposits of the Rhynie outlier, Scotland. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 97, 167–211. ( 10.1017/S0263593300001449) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mark DF, Rice CM, Trewin NH. 2013. Discussion on ‘A high-precision U–Pb age constraint on the Rhynie Chert Konservat-Lagerstätte: time scale and other implications': Journal, Vol. 168, 863–872. J. Geol. Soc. 170, 701–703. ( 10.1144/jgs2011-110) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parry SF, Noble SR, Crowley QG, Wellman CH. 2013. Reply to Discussion on ‘A high-precision U–Pb age constraint on the Rhynie Chert Konservat-Lagerstätte: time scale and other implications’: Journal, 168, 863–872. J. Geol. Soc. 170, 703–706. ( 10.1144/jgs2012-089) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gradstein FM, Ogg JG, Schmitz MD, Ogg GM. 2012. The geologic time scale, 2012. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackie W. 1914. The rock series of Craigbeg and Ord Hill, Rhynie, Aberdeenshire. Trans. Edinb. Geol. Soc. 10, 205–236. ( 10.1144/transed.10.2.205) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trewin NH. 2004. History of research on the geology and palaeontology of the Rhynie area Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 285–297. ( 10.1017/S0263593300000699) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott DH. 1920. Studies in fossil botany. Vol 1: pteridophyta, 3 edn London, UK: Black. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson JW. 1859. On fossil plants from the Devonian rocks of Canada. Q. J. Geol. Soc. 15, 477–488. ( 10.1144/GSL.JGS.1859.015.01-02.57) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bierhorst DW. 1968. On the Stromatopteridaceae (fam. nov) and the Psilotaceae. Phytomorphology 18, 232–268. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wickett NJ, et al. 2014. Phylotranscriptomic analysis of the origin and early diversification of land plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E4859–E4868. ( 10.1073/pnas.1323926111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruhfel B, Gitzendanner M, Soltis P, Soltis D, Burleigh J. 2014. From algae to angiosperms—inferring the phylogeny of green plants (Viridiplantae) from 360 plastid genomes. BMC Evol. Biol. 14, 23 ( 10.1186/1471-2148-14-23) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearson HL. 2014. Gender-bending in the Devonian at Rhynie and afterwards. The Linnean 30, 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerp H. 2017. Organs and tissues of Rhynie chert plants. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160495 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0495) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duckett JG, Pressel S. 2017. The evolution of the stomatal apparatus: intercellular spaces and sporophyte water relations in bryophytes—two ignored dimensions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160498 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0498) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raven JA. 2017. Evolution and palaeophysiology of the vascular system and other means of long-distance transport. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160497 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0497) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kenrick P. 2017. Changing expressions: a hypothesis for the origin of the vascular plant life cycle. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20170149 ( 10.1098/rstb.2017.0149) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cove D, Bezanilla M, Harries P, Quatrano R. 2006. Mosses as model systems for the study of metabolism and development. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 497–520. ( 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105338) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rensing SA, et al. 2008. The Physcomitrella genome reveals evolutionary insights into the conquest of land by plants. Science 319, 64–69. ( 10.1126/science.1150646) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honkanen S, et al. 2016. The mechanism forming the cell surface of tip-growing rooting cells is conserved among land plants. Curr. Biol. 26, 3238–3244. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Banks JA, et al. 2011. The Selaginella genome identifies genetic changes associated with the evolution of vascular plants. Science 332, 960–963. ( 10.1126/science.1203810) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hetherington AJ, Dolan L. 2017. Bilaterally symmetric axes with rhizoids composed the rooting structure of the common ancestor of vascular plants. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20170042 ( 10.1098/rstb.2017.0042) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrison CJ, Morris JL. 2017. The origin and early evolution of vascular plant shoots and leaves. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160496 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0496) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kofuji R, Yagita Y, Murata T, Hasebe M. 2017. Antheridial development in the moss Physcomitrella patens: implications for understanding stem cells in mosses. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160494 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0494) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strullu-Derrien C, Spencer ART, Goral T, Dee J, Honegger R, Kenrick P, Longcore JE, Berbee ML. 2017. New insights into the evolutionary history of Fungi from a 407 MA Blastocladiomycota fossil showing a complex hyphal thallus. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160502 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0502) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Honegger R, Edwards D, Axe L, Strullu-Derrien C. 2017. Fertile Prototaxites taiti: a basal ascomycete with inoperculate, polysporous asci lacking croziers. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20170146 ( 10.1098/rstb.2017.0146) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirst S. 1923. On some arachnid remains from the Old Red Sandstone (Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire). Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. 12, 455–474. ( 10.1080/00222932308632963) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirst S, Maulik S. 1926. On some arthropod remains from the Rhynie Chert (Old Red Sandstone). Geol. Mag. 63, 69–71. ( 10.1017/S0016756800083692) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scourfield DJ. 1926. On a new type of crustacean from the Old Red Sandstone (Rhynie chert Bed, Aberdeenshire) – Lepidocaris rhyniensis, gen. et sp. nov. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 214, 153–187. ( 10.1098/rstb.1926.0005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poinar G, Kerp H, Hass H. 2008. Palaeonema phyticum gen. n., sp n. (Nematoda: Palaeonematidae fam. n.), a Devonian nematode associated with early land plants. Nematology 10, 9–14. ( 10.1163/156854108783360159) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haug C. 2017. Feeding strategies in arthropods from the Rhynie and Windyfield cherts: ecological diversification in an early non-marine biota. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160492 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0492) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunlop JA, Garwood RJ. 2017. Terrestrial invertebrates in the Rhynie chert ecosystem. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160493 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0493) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyon AG. 1964. Probable fertile region of Asteroxylon mackiei K., and L. Nature 203, 1082–1083. ( 10.1038/2031082b0)14223093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kerp H, Hass H, Mosbrugger V. 2001. New data on Nothia aphylla Lyon 1964 ex El-Saadawy et Lacey 1979, a poorly known plant from the Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert. In Plants invade the land: evolutionary and environmental perspectives (eds Gensel PG, Edwards D), pp. 52–82. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Claridge MF, Lyon AG. 1961. Lung-books in the Devonian Palaeocharinidae (Arachnida). Nature 191, 1190–1191. ( 10.1038/1911190b0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards DS. 1986. Aglaophyton major, a non-vascular land plant from the Devonian Rhynie Chert. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 93, 173–204. ( 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1986.tb01020.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards DS. 1980. Evidence for the sporophytic status of the Lower Devonian plant Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii Kidston and Lang. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 29, 177–188. ( 10.1016/0034-6667(80)90057-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Remy W, Remy R. 1980. Devonian gametophytes with anatomically preserved gametangia. Science 208, 295–296. ( 10.1126/science.208.4441.295) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Remy W, Gensel PG, Hass H. 1993. The gametophyte generation of some early Devonian land plants. Int. J. Plant Sci. 154, 35–58. ( 10.1086/297089) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krings M, Harper CJ, Taylor EL. 2017. Fungi and fungal interactions in the Rhynie chert: a review of the evidence, with the description of Perexiflasca tayloriana gen. et sp. nov. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160500 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0500) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Remy W, Taylor TN, Hass H, Kerp H. 1994. Four hundred-million-year-old vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 11 841–11 843. ( 10.1073/pnas.91.25.11841) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor TN, Hass H, Kerp H, Krings M, Hanlin RT. 2005. Perithecial ascomycetes from the 400 million year old Rhynie Chert; an example of ancestral polymorphism. Mycologia 97, 269–285. ( 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832862) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor TN, Hass H, Remy W, Kerp H. 1995. The oldest fossil lichen. Nature 378, 244 ( 10.1038/378244a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Taylor TN, Remy W, Hass H. 1992. Parasitism in a 400-million-year-old green alga. Nature 357, 493–494. ( 10.1038/357493a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor TN, Klavins SD, Krings M, Taylor EL, Kerp H, Hass H. 2004. Fungi from the Rhynie Chert: a view from the dark side. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 457–473. ( 10.1017/S026359330000081X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pirozynski KA, Malloch DW. 1975. The origin of land plants: a matter of mycotrophism. Biosystems 6, 153–164. ( 10.1016/0303-2647(75)90023-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strullu-Derrien C, Kenrick P, Pressel S, Duckett JG, Rioult JP, Strullu DG. 2014. Fungal associations in Horneophyton ligneri from the Rhynie Chert (ca – 407 Ma) closely resemble those in extant lower land plants: novel insights into ancestral plant–fungus symbioses. New Phytol. 203, 964–979. ( 10.1111/nph.12805) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bidartondo MI, Read DJ, Trappe JM, Merckx V, Ligrone R, Duckett JG. 2011. The dawn of symbiosis between plants and fungi. Biol. Lett. 7, 574–577. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1203) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lenton TM, Crouch M, Johnson M, Pires N, Dolan L. 2012. First plants cooled the Ordovician. Nat. Geosci. 5, 86–89. ( 10.1038/ngeo1390) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Field KJ, Cameron DD, Leake JR, Tille S, Bidartondo MI, Beerling DJ. 2012. Contrasting arbuscular mycorrhizal responses of vascular and non-vascular plants to a simulated Palaeozoic CO2 decline. Nat. Commun. 3, 835 ( 10.1038/ncomms1831) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Field KJ, Rimington WR, Bidartondo MI, Allinson KE, Beerling DJ, Cameron DD, Duckett JG, Leake JR, Pressel S. 2015. First evidence of mutualism between ancient plant lineages (Haplomitriopsida liverworts) and Mucoromycotina fungi and its response to simulated Palaeozoic changes in atmospheric CO2. New Phytol. 205, 743–756. ( 10.1111/nph.13024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Franks PJ, Royer DL, Beerling DJ, Van de Water PK, Cantrill DJ, Barbour MM, Berry JA. 2014. New constraints on atmospheric CO2 concentration for the Phanerozoic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 4685–4694. ( 10.1002/2014GL060457) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mills BJW, Batterman SA, Field KJ. 2017. Nutrient acquisition by symbiotic fungi governs Palaeozoic climate transition. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160503 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0503) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rice CM, Trewin NH. 1988. A Lower Devonian gold-bearing hot spring system near Rhynie, Scotland. Trans. Inst. Mining Metall. 97, B141–B144. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powell CL, Trewin NH, Edwards D. 2000. Palaeoecology and plant succession in a borehole through the Rhynie cherts, Lower Old Red Sandstone, Scotland. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 180, 439–457. ( 10.1144/GSL.SP.2000.180.01.23) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trewin NH, Wilson E. 2004. Correlation of the Early Devonian Rhynie chert beds between three boreholes at Rhynie, Aberdeenshire. Scott. J. Geol. 40, 73–81. ( 10.1144/sjg40010073) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dunlop JA, Anderson LI, Kerp H, Hass H. 2004. A harvestman (Archnida, Opiliones) from the Early Devonian Rhynie cherts, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 341–354. ( 10.1017/S0263593300000730) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fayers SR, Trewin NH. 2004. A review of the palaeoenvironments and biota of the Windyfield Chert. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 325–339. ( 10.1017/S0263593300000729) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fayers SR, Trewin NH. 2003. A new crustacean from the Early Devonian Rhynie Chert, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 93, 355–382. ( 10.1017/S026359330000047X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Powell CL, Edwards D, Trewin NH. 1999. A new vascular plant from the Lower Devonian Windyfield Chert, Rhynie, NE Scotland. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 90, 331–349. ( 10.1017/S0263593300002662) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lyon AG, Edwards D. 1991. The first zosterophyll from the Lower Devonian Rhynie Chert, Aberdeenshire. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 82, 323–332. ( 10.1017/S0263593300004193) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fayers SR, Trewin NH. 2005. A hexapod from the Early Devonian Windyfield Chert, Rhynie, Scotland. Palaeontology 48, 1117–1130. ( 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2005.00501.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Anderson LI, Trewin NH. 2003. An Early Devonian arthropod fauna from the Windyfield cherts, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Palaeontology 46, 467–510. ( 10.1111/1475-4983.00308) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fayers SR, Dunlop JA, Trewin NH. 2004. A new Early Devonian trigonotarbid arachnid from the Windyfield Chert, Rhynie, Scotland. J. Syst. Palaeontol. 2, 269–284. ( 10.1017/S147720190400149X) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson LI, Crighton WRB, Hass H. 2004. A new univalve crustacean from the Early Devonian Rhynie chert hot-spring complex. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 355–369. ( 10.1017/S0263593300000742) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haug C, Haug JT, Fayers SR, Trewin NH, Castellani C, Waloszek D, Maas A. 2012. Exceptionally preserved nauplius larvae from the Devonian Windyfield chert, Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Palaeontol. Electronica 15(2), 24 (http://palaeo-electronica.org/content/2012-issue-2-articles/287-nauplius-larva-in-chert) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Trewin NH, Fayers SR. 2016. Macro to micro aspects of the plant preservation in the Early Devonian Rhynie cherts, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Earth Env. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 106, 67–80. ( 10.1017/S1755691016000025) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trewin NH, Fayers SR, Kelman R. 2003. Subaqueous silicification of the contents of small ponds in an Early Devonian hot-spring complex, Rhynie, Scotland. Can. J. Earth Sci. 40, 1697–1712. ( 10.1139/e03-065) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Channing A. 2017. A review of active hot-spring analogues of Rhynie: environments, habitats and ecosystems. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160490 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0490) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Channing A, Edwards D. 2004. Experimental taphonomy; silicification of plants in Yellowstone hot-spring environments. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. Earth Sci. 94, 503–521. ( 10.1017/S0263593300000845) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Channing A, Edwards D. 2009. Yellowstone hot spring environments and the palaeo-ecophysiology of Rhynie chert plants: towards a synthesis. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2, 111–143. ( 10.1080/17550870903349359) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wellman CH. 2017. Palaeoecology and palaeophytogeography of the Rhynie chert plants: further evidence from integrated analysis of in situ and dispersed spores. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160491 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0491) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Strullu-Derrien C, Goral T, Longcore JE, Olesen J, Kenrick P, Edgecombe GD. 2016. A new chytridiomycete fungus intermixed with crustacean resting eggs in a 407-million-year-old continental freshwater environment. PLoS ONE 11, e0167301 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0167301) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abbott GD, Fletcher IW, Tardio S, Hack E. 2017. Exploring the geochemical distribution of organic carbon in early land plants: a novel approach. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373, 20160499 ( 10.1098/rstb.2016.0499) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This article has no additional data.