INTRODUCTION

Placebo analgesia refers to pain relief due to the psychosocial context surrounding treatments and interventions [10; 55]. Placebo analgesic effects are influenced by many factors, including expectancies about treatments, previous experiences, as well as other cognitive and emotional elements [12]. Within these factors, previous experience via conditioning is one of the most studied mechanisms of neurobiological investigation of placebo effects and findings from this line of inquiry have suggested that conditioning, instructional, and observational cues work to change expectancy of treatment which in turn changes clinical outcomes [13; 9; 53]. In keeping with this, the mere expectation of analgesia from receiving a treatment (e.g. a painkiller) can reduce pain perception, even if this treatment is in fact an inert substance (e.g. placebo, [55]). This expectancy can be acquired in a number of ways including direct experience of analgesia (i.e. the patient learns that after taking a specific drug, pain will decrease), verbal instructions (i.e. the doctor tells the patient that a specific drug will reduce pain) or social observation (i.e. the patient observes pain relief in another patient after this patient took a specific drug) [8].

Given that humans are highly sociable organisms and that our behaviors are affected by social learning, the ability for social observation to generate treatment expectations that in turn alter clinical response is likely a fruitful area of study, particularly with regard to how social learning can be used to enhance analgesic responses and reduce hyperalgesic responses in the clinic [18; 48; 42]. In this review, we used both terms ‘social’ and ‘observational’ learning to allude to the pain modulation that a study participant or patient experiences due to social information [18; 48; 42]. While observational learning refers primarily to acquiring information through directly observing another patient receiving pain relief, social learning incorporates the entire interpersonal context that leads to behavioral changes.

We conducted a literature search of PubMed using the following set of terms: pain, social learning, and placebo; pain, nocebo, and observation. We found 19 and 7 articles respectively and we manually selected seven references on socially-induced placebo and nocebo effects considered most relevant for this topical review (see references marked with *). We excluded observational pain studies, and case series but we discuss reviews that support the discussion on potential mechanisms underpinning socially-induced placebo and nocebo pain modulatory effects.

PLACEBO PAIN MODULATION AND SOCIAL LEARNING

Social learning influences pain perception [59] in laboratory settings [27; 19] and clinical contexts (e.g. abdominal pain) in adults and children [34; 35]. Children who observed their mothers exaggerate painful reactions to cold water subsequently presented lower pain thresholds [26]. Modeling and social learning may also contribute to the etiology of abdominal pain [58].

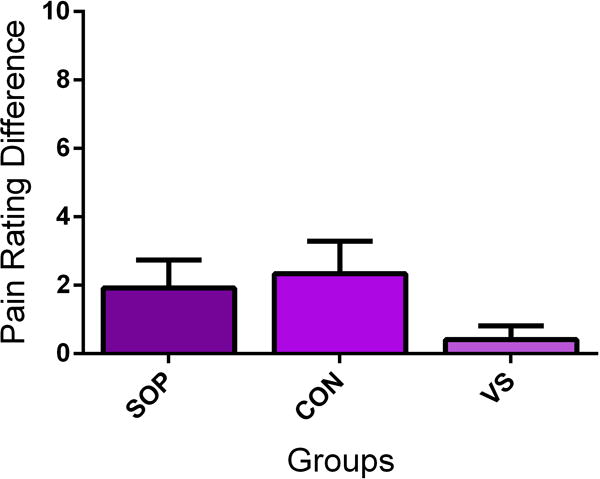

Posited by Bootzin and Caspi [6], observationally learned placebo analgesia has been demonstrated empirically by Colloca and Benedetti who first studied observational learning as a model to modulate pain experience in participants observing a demonstrator receiving both electrical pain and analgesia [11]. In the experiment, the participant sat close to the demonstrator receiving painful and non-painful electrical stimulations while a set of two cues (either red or green) were displayed in front of them. The demonstrator repeatedly rated the pain stimulus higher after the red cue and lower after the green cue. Participants had to pay attention to the lights displayed on a monitor, with particular regard to their meaning. Therefore, through social learning, the participant was made to believe that the green cue was followed by a non-painful stimulus while the red cue was followed by a painful stimulus. Afterwards, participants received painful electric stimulations after the red and green cues themselves. However, the level of pain was surreptitiously set at the same intensity and any changes in pain reports were operationally defined as the results of learning and expectations formed via observation and participants showed a strong placebo analgesic effect (the difference in green cue versus red cue pain ratings). This placebo manipulation generates expectancies which lead to placebo effects of similar sizes to those shown through direct experience via conditioning paradigms (percentage pain reduction in the observational learning and conditioning group: 39.18% versus 43.35%; Fig. 1A, B). Thus, social observation was strong enough to boost analgesia and expectancy of pain relief [11].

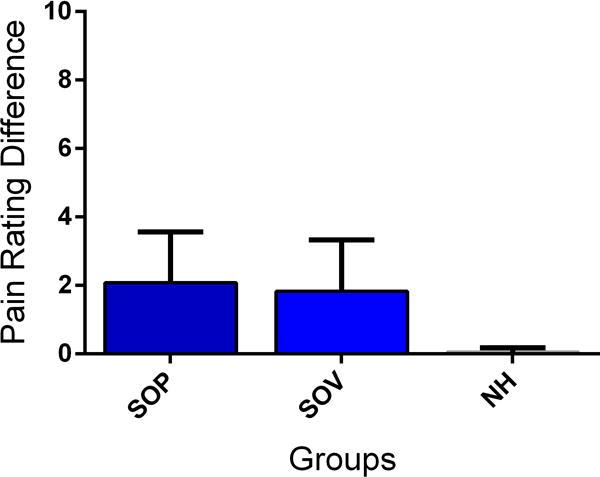

Figure 1. Social learning and placebo analgesia.

Observation (SOP) produces a similar placebo analgesic effect to direct conditioning (CON) and larger effect than verbally-induced analgesia (eg, instructions only, VS) (A). Observation leads to similar effects if the participant is observing a live demonstrator (SOP) or a video presentation (SOV) (B). Pain intensity was measured using a Numerical rating Scale ranging from 0=no pain to 10= maximum tolerable pain. Pain rating difference refers to the difference between the ratings for the two presented visual cues. The painful intensity accompanying both cues was equal and any difference is operationally defined as a placebo analgesic effect. Data from [11] and [28], respectively. Abbreviations: SOP = Social Observation in person; CON = Conditioning; VS = Verbal instruction; SOV = Social observation via video; NH = Natural History.

After this pioneering study [11], other studies have replicated and extended these findings [3; 21; 28; 50; 51; 54]. These studies confirm that the placebo effect of observational learning is comparable in size to the effect of directly experienced conditioning. For example, Egorova and colleagues also compared conditioning versus observationally-induced effects in an experiment which included alternating sessions of directly experienced conditioning and observational learning in a counterbalanced within design [21]. For direct conditioning, the participant learned to associate certain pain levels with specific cues after directly experiencing the pain, however, with observationally-induced conditioning the participant watched someone else undergo direct experience of low and high painful stimulations. During the testing phase after direct or observational learning, the researchers presented a novel cue, the conditioning cues supraliminally (for 200 ms), and the same conditioning cues subliminally (33 ms + 167 ms mask). In this way, the researchers could directly test the relative strength of direct versus observationally learned placebo/nocebo effects and probe if this pain modulation was a conscious or unconscious phenomenon. The findings revealed comparable magnitudes for both placebo and nocebo effects induced by conditioning and observational learning in line with previous results [11]. Interestingly, there was also a modulatory effect from the subliminally presented cues, suggesting that the placebo and nocebo effects have a strong unconscious (or subconscious) component.

Observational learning has been extensively studied in the area of fear [39; 40] and recently also in the context of observationally-induced hyperalgesia. For example, Vogtle and colleagues assigned female healthy participants to a control, verbal suggestion, or observational learning group [54]. The control group was given an open-labeled placebo cream with instructions of ineffectiveness. Those in the verbal suggestion group were told that the cream would enhance their pain. The observational learning group watched a video clip in which a demonstrator showed increased pain when the cream was applied. All participants were tested for nocebo hyperalgesic effects using high pressure painful stimuli on their hands. Pain reports in the control and verbal suggestion groups were the same. However, participants in the observational group experienced higher pain after watching the demonstrator and these responses were correlated with pain catastrophizing scores, indicating the importance of studying the mechanisms underlying observational learning, psychological traits and hyperalgesia [39].

The authors attempted to separate instructions from observational learning, but this is challenging to accomplish. The entire set of psychosocial cues (e.g. salience, attention, arousal related to the environmental cues) and interpersonal interactions contribute to social learning and can induce expectancy that potentially consolidate hyperalgesia (and hypoalgesia) affecting pain experience and processing (and other symptoms) and the likelihood that the observer translates the knowledge into actions.

A recent study informed one person within a socially interacting group that high altitude can cause headaches. Once the group visited a high altitude facility, the peers that received the information showed higher frequency of high altitude headache symptoms as well as changes in their prostaglandin levels compared to the peers that did not receive the information. This work shows convincingly that social learning and negative expectancies can spread across groups causing nocebo effects on a group level [3].

Two recent studies have also showed that seeing painful ratings from other people influenced the way participants experienced painful stimuli themselves as well as related physiological responses (e.g. skin conductance; brain activity) [30; 60]. In particular, study participants were asked to observe pain ratings of a group of people about a specific pain stimulus, before receiving the same pain stimulus themselves. The observed rating induced similar subjective pain reports and the variance of the observed ratings elicited a robust hyperalgesic effect with the modulation of the brainstem pain system [60].

POTENTIAL MECHANISMS OF OBSERVATIONALLY-INDUCED PAIN CHANGES

The studies presented above show that placebo analgesia can be learned through social modeling and observational learning. Importantly, observationally-induced placebo or nocebo effects in the area of pain point to a phenomenon that is not merely a report bias to please the experimenters. However, the mechanisms behind this phenomenon are still underexplored. Here we present mechanisms likely to be involved in observationally-induced placebo analgesia.

Observing the repetition of associations in which one cue is continuously associated with hypoalgesia (or analgesia) and another cue is associated with a hyperalgesic level of pain led to significant pain modulation in observers. The observation of the hypoalgesic and hyperalgesic experience in a demonstrator may act as an unconditioned stimulus, suggesting possible commonalities between observational learning and direct learning processes such as classical and operant conditioning. Even though no study has asked participants for their expectations after the observation phase, it is likely that the observation of pain modulation results in the de-novo acquisition or consolidation of implicit and explicit expectancies of pain relief which in turn activates the descending modulatory systems.

1. Empathy, Mentalizing and Mirror neurons

In order to learn through the observation of others it is important to understand what the observed person is feeling and experiencing. Social cognition mechanisms like empathy and mentalizing are critical processes for this type of understanding and are therefore likely to be involved in socially-induced placebo analgesia. Empathy refers to the ability to share an emotional experience when another person feels a similar emotion [43]. The vicarious experience of pain during observation might enable the association of unconditioned stimulus and conditioned stimulus in social learning. Evidence for the involvement of empathy processes stems from the studies demonstrating that individual empathy scores (“empathic concern”) were correlated with the strength of socially-induced placebo analgesia [11]. Although, observationally-induced changes in pain levels were correlated with pain modulation when live demonstrators were involved in the experimental settings, no association was observed when watching a demonstrator in a video recording. This suggests that the involvement of empathy is stronger when the demonstrator is physically present and interpersonal interactions are involved (Fig. 1B) [28].

By contrast, mentalizing refers to the ability to cognitively understand mental states of others [24]. In order to learn from observation, it is necessary to understand where the relief of the other person is coming from and to attribute it to the treatment. However, direct evidence for the involvement of mentalizing processes in social learning of pain modulation is still lacking.

We might also speculate the mirror system could be another mechanism involved in observationally-induced pain modulation [45–47]. The mirror system helps initiate behaviors [38; 41] when we observe for example another person performing an action (e.g. grabbing an apple on the table) [7] or experiencing an emotion (e.g. showing a painful face when high pain is delivered) [25]. Within this framework, facial expressions, in particular, are an important source of information and emotions, and it appears that the mirror systems pick up on another’s expressions and help initiate a similar emotional state conveyed through facial expressions. A passive observation of facial expressions, such as a painful facial expression associated with high pain and a smiling facial expression associated with low pain, significantly interacted with placebo analgesia, with both facial expressions leading to an increase of the analgesic effect [52].

2. Endogenous modulatory systems

Endogenous systems are involved in the descending modulation of pain [12] and placebo analgesic effects can be substantially reduced by opioid [1; 4; 22; 33] and non-opioid [2] antagonists. Very recently, it has been shown that the neuropeptide vasopressin [14] and oxytocin [29; 14] boost placebo analgesia induced by verbal suggestions. These hormones are regulated in a sexually dimorphic manner [44] and may be important for observationally-induced pain modulation due their substantial role in regulating social behaviors in humans [20].

Placebo effects on pain are largely mediated by the descending pain modulatory system [10; 23]. Several studies implicate functional connectivity between the rostral anterior cingulate and the periaqueductal gray, a region critical for descending pain modulation, and conditioned placebo analgesia [5; 22; 56]. Additionally, there is considerable evidence that prefrontal regions, especially the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, are critically involved in placebo analgesia [32]. The prefrontal cortex consistently shows higher activations related to the anticipation of analgesia and experience of pain relief induced by a placebo manipulation [56], and is involved in the acquisition of expectancies during conditioning of placebo analgesia [37; 57]. Therefore the current understanding is that the prefrontal cortex maintains and updates expectancies regarding pain [36], and that these prefrontal regions influence the experience of pain by activating the descending pain modulatory system [56]. Research on somatic and empathic (vicarious) pain can also inform future research on socially-induced placebo (and nocebo) pain modulation. Vicarious and somatic types of pain have commonalities at the neural level [15; 49] with overlapping activations in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, anterior insula, and other areas. Nevertheless, these activations appear to be unspecific to pain and rather related to negative affect [16; 31].

CONCLUSIONS

In this review, we illustrated how pain modulation can be learned through social information. Despite the limited evidence for the neural mechanisms underpinning socially-induced states of analgesia, hypoalgesia and hyperalgesia, we can speculate that empathy, mentalizing and mirror processes [61], via automatic and cognitively controlled mechanisms [17] and with a potential involvement of the vasopressin and oxytocin systems [14; 29], are engaged in this form of pain modulation. This line of research is highly relevant for pain medicine as well as clinical trial methodology. Social information and interactions are ubiquitously present in these settings and patients and study participants interact with each other, influencing individual pain experiences. Potential applications may include the observation of other patients’ therapeutic experience (e.g. video clips) to optimize expectancies of the observer and translate clinical knowledge into behavioral changes. Principles of social learning can be applied to pain therapies that tailor the patient’s family and caregivers. It is important to understand when and how socially-induced modulation of pain occurs with an appreciation of the potential differences between experimental versus clinical settings as well the mediatory role of emotional processes (i.e. catastrophizing). This review outlines an innovative research that warrants future investigation and opens up new avenues to understand how humans process pain in social contexts and allows for future improvement of therapeutic approaches and tools to help patients cope with pain.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the University of Maryland, Baltimore (LC) and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR, R01DE025946, LC).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest.

LC received lecture honoraria (Georgetown University and Stanford University) and has acted as speaker or consultant for Grünenthal and Emmi Solution. LS and SRK have no conflicts of interest to be declared.

References

- 1.Amanzio M, Benedetti F. Neuropharmacological dissection of placebo analgesia: expectation-activated opioid systems versus conditioning-activated specific subsystems. J Neurosci. 1999;19(1):484–494. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-01-00484.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benedetti F, Amanzio M, Rosato R, Blanchard C. Nonopioid placebo analgesia is mediated by CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Nat Med. 2011;17(10):1228–1230. doi: 10.1038/nm.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *3.Benedetti F, Durando J, Vighetti S. Nocebo and placebo modulation of hypobaric hypoxia headache involves the cyclooxygenase-prostaglandins pathway. Pain. 2014;155(5):921–928. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benedetti F, Pollo A, Colloca L. Opioid-mediated placebo responses boost pain endurance and physical performance: is it doping in sport competitions? J Neurosci. 2007;27(44):11934–11939. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3330-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bingel U, Lorenz J, Schoell E, Weiller C, Buchel C. Mechanisms of placebo analgesia: rACC recruitment of a subcortical antinociceptive network. Pain. 2006;120(1-2):8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bootzin RR, Caspi O. Explanatory mechanisms for placebo effects: cognition, personality and social learning. In: Guess HA, Kleinman A, Kusek JW, Engel LW, editors. The Science of the Placebo Toward an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda. London: BMJ Books; 2002. pp. 108–132. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chartrand TL, Bargh JA. The chameleon effect: the perception-behavior link and social interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(6):893–910. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colagiuri B, Schenk LA, Kessler MD, Dorsey SG, Colloca L. The placebo effect: From concepts to genes. Neuroscience. 2015;307:171–190. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colloca L. Placebo, nocebo, and learning mechanisms. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;225:17–35. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-44519-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colloca L, Benedetti F. Placebos and painkillers: is mind as real as matter? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(7):545–552. doi: 10.1038/nrn1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *11.Colloca L, Benedetti F. Placebo analgesia induced by social observational learning. Pain. 2009;144(1-2):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colloca L, Klinger R, Flor H, Bingel U. Placebo analgesia: psychological and neurobiological mechanisms. Pain. 2013;154(4):511–514. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colloca L, Miller FG. How placebo responses are formed: a learning perspective. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2011;366(1572):1859–1869. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colloca L, Pine DS, Ernst M, Miller FG, Grillon C. Vasopressin Boosts Placebo Analgesic Effects in Women: A Randomized Trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(10):794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corradi-Dell’Acqua C, Hofstetter C, Vuilleumier P. Felt and seen pain evoke the same local patterns of cortical activity in insular and cingulate cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31(49):17996–18006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2686-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corradi-Dell’Acqua C, Tusche A, Vuilleumier P, Singer T. Cross-modal representations of first-hand and vicarious pain, disgust and fairness in insular and cingulate cortex. Nature communications. 2016;7:10904. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig KD, Versloot J, Goubert L, Vervoort T, Crombez G. Perceiving pain in others: automatic and controlled mechanisms. J Pain. 2010;11(2):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Montmollin G, Perlmutter HV. Learning in group; experience in social psychology. Enfance; psychologie, pedagogie, neuropsychiatrie, sociologie. 1951;4(4):359–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Ruddere L, Goubert L, Vervoort T, Kappesser J, Crombez G. Impact of being primed with social deception upon observer responses to others’ pain. Pain. 2013;154(2):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donaldson ZR, Young LJ. Oxytocin, vasopressin, and the neurogenetics of sociality. Science. 2008;322(5903):900–904. doi: 10.1126/science.1158668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *21.Egorova N, Park J, Orr SP, Kirsch I, Gollub RL, Kong J. Not seeing or feeling is still believing: conscious and non-conscious pain modulation after direct and observational learning. Scientific reports. 2015;5:16809. doi: 10.1038/srep16809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eippert F, Bingel U, Schoell ED, Yacubian J, Klinger R, Lorenz J, Buchel C. Activation of the opioidergic descending pain control system underlies placebo analgesia. Neuron. 2009;63(4):533–543. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fields H. State-dependent opioid control of pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(7):565–575. doi: 10.1038/nrn1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frith CD, Frith U. The neural basis of mentalizing. Neuron. 2006;50(4):531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallese V, Keysers C, Rizzolatti G. A unifying view of the basis of social cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8(9):396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman JE, McGrath PJ. Mothers’ modeling influences children’s pain during a cold pressor task. Pain. 2003;104(3):559–565. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goubert L, Vlaeyen JW, Crombez G, Craig KD. Learning about pain from others: an observational learning account. J Pain. 2011;12(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *28.Hunter T, Siess F, Colloca L. Socially induced placebo analgesia: a comparison of a pre-recorded versus live face-to-face observation. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(7):914–922. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2013.00436.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessner S, Sprenger C, Wrobel N, Wiech K, Bingel U. Effect of oxytocin on placebo analgesia: a randomized study. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1733–1735. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koban L, Wager TD. Beyond conformity: Social influences on pain reports and physiology. Emotion. 2016;16(1):24–32. doi: 10.1037/emo0000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krishnan A, Woo CW, Chang LJ, Ruzic L, Gu X, Lopez-Sola M, Jackson PL, Pujol J, Fan J, Wager TD. Somatic and vicarious pain are represented by dissociable multivariate brain patterns. eLife. 2016;5:e15166. doi: 10.7554/eLife.15166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krummenacher P, Candia V, Folkers G, Schedlowski M, Schonbachler G. Prefrontal cortex modulates placebo analgesia. Pain. 2010;148(3):368–374. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levine JD, Gordon NC, Fields HL. The mechanism of placebo analgesia. Lancet. 1978;2(8091):654–657. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)92762-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy RL, Jones KR, Whitehead WE, Feld SI, Talley NJ, Corey LA. Irritable bowel syndrome in twins: heredity and social learning both contribute to etiology. Gastroenterology. 2001;121(4):799–804. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.27995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levy RL, Langer SL, Whitehead WE. Social learning contributions to the etiology and treatment of functional abdominal pain and inflammatory bowel disease in children and adults. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2007;13(17):2397–2403. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lorenz J, Hauck M, Paur RC, Nakamura Y, Zimmermann R, Bromm B, Engel AK. Cortical correlates of false expectations during pain intensity judgments–a possible manifestation of placebo/nocebo cognitions. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(4):283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lui F, Colloca L, Duzzi D, Anchisi D, Benedetti F, Porro CA. Neural bases of conditioned placebo analgesia. Pain. 2010;151(3):816–824. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newman-Norlund RD, van Schie HT, van Zuijlen AM, Bekkering H. The mirror neuron system is more active during complementary compared with imitative action. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(7):817–818. doi: 10.1038/nn1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olsson A, Nearing KI, Phelps EA. Learning fears by observing others: the neural systems of social fear transmission. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2(1):3–11. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olsson A, Phelps EA. Social learning of fear. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(9):1095–1102. doi: 10.1038/nn1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oosterhof NN, Tipper SP, Downing PE. Crossmodal and action-specific: neuroimaging the human mirror neuron system. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(7):311–318. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Poulin-Dubois D, Brosseau-Liard P. The Developmental Origins of Selective Social Learning. Current directions in psychological science. 2016;25(1):60–64. doi: 10.1177/0963721415613962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Preston SD, de Waal FB. Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav Brain Sci. 2002;25(1):1–20. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000018. discussion 20-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rilling JK, Demarco AC, Hackett PD, Chen X, Gautam P, Stair S, Haroon E, Thompson R, Ditzen B, Patel R, Pagnoni G. Sex differences in the neural and behavioral response to intranasal oxytocin and vasopressin during human social interaction. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rizzolatti G, Fabbri-Destro M. The mirror system and its role in social cognition. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18(2):179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rizzolatti G, Fabbri-Destro M, Cattaneo L. Mirror neurons and their clinical relevance. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2009;5(1):24–34. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rizzolatti G, Sinigaglia C. The mirror mechanism: a basic principle of brain function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17(12):757–765. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scott DV. Social learning. Queen’s nursing journal. 1974;17(5):100. passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sharvit G, Vuilleumier P, Delplanque S, Corradi-Dell’Acqua C. Cross-modal and modality-specific expectancy effects between pain and disgust. Scientific reports. 2015;5:17487. doi: 10.1038/srep17487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *50.Swider K, Babel P. The effect of the sex of a model on nocebo hyperalgesia induced by social observational learning. Pain. 2013;154(8):1312–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *51.Swider K, Babel P. The Effect of the Type and Colour of Placebo Stimuli on Placebo Effects Induced by Observational Learning. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0158363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Valentini E, Martini M, Lee M, Aglioti SM, Iannetti GD. Seeing facial expressions enhances placebo analgesia. Pain. 2014;155(4):666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vase L, Amanzio M, Price DD. Nocebo vs. placebo: the challenges of trial design in analgesia research. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97(2):143–150. doi: 10.1002/cpt.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *54.Vogtle E, Barke A, Kroner-Herwig B. Nocebo hyperalgesia induced by social observational learning. Pain. 2013;154(8):1427–1433. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wager TD, Atlas LY. The neuroscience of placebo effects: connecting context, learning and health. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(7):403–418. doi: 10.1038/nrn3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wager TD, Rilling JK, Smith EE, Sokolik A, Casey KL, Davidson RJ, Kosslyn SM, Rose RM, Cohen JD. Placebo-induced changes in FMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science. 2004;303(5661):1162–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.1093065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watson A, El-Deredy W, Iannetti GD, Lloyd D, Tracey I, Vogt BA, Nadeau V, Jones AK. Placebo conditioning and placebo analgesia modulate a common brain network during pain anticipation and perception. Pain. 2009;145(1-2):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Heller BR, Robinson JC, Schuster MM, Horn S. Modeling and reinforcement of the sick role during childhood predicts adult illness behavior. Psychosom Med. 1994;56(6):541–550. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199411000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams AC. Facial expression of pain: an evolutionary account. Behav Brain Sci. 2002;25(4):439–455. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000080. discussion 455-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshida W, Seymour B, Koltzenburg M, Dolan RJ. Uncertainty increases pain: evidence for a novel mechanism of pain modulation involving the periaqueductal gray. J Neurosci. 2013;33(13):5638–5646. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4984-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zaki J, Wager TD, Singer T, Keysers C, Gazzola V. The Anatomy of Suffering: Understanding the Relationship between Nociceptive and Empathic Pain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20(4):249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]