Summary

Based on revisions of Gleason scoring in 2005, it has been reported that nodal metastases at radical prostatectomy in Gleason 3 + 3 = 6 (GS6) prostate cancer are extremely rare, and that GS6 cancers with nodal metastases are invariably upgraded upon review by academic urological pathologists. We analysed the prevalence and determinants of nodal metastases in a national sample of patients with GS6 cancer. We utilised the SEER database to identify patients diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancer during 2004–2010 who had radical prostatectomy and ≥1 lymph node(s) examined. We calculated the prevalence of nodal metastases and constructed a multivariable logistic regression model to identify factors associated with nodal metastases. Among 21,960 patients, the prevalence of nodal metastases was 0.48%. Older age, preoperative PSA >10 ng/mL, and advanced stage were positively associated with nodal metastases. Lymph node metastases in GS6 cancer are more prevalent in a nationwide population compared to academic centres. Revised guidelines for Gleason scoring have made GS6 cancer a more homogeneously indolent disease, which may be relevant in the era of active surveillance. We submit that lymph node metastases in GS6 cancer be used as a proxy for adherence to the 2005 ISUP consensus on Gleason grading.

Keywords: Gleason score, lymph node metastasis, prostatic neoplasms, SEER Program

INTRODUCTION

The Gleason scoring system was originally created in 1966, and has endured as an important prognosticator for prostate cancer.1,2 The scoring system has evolved over time, and in 2005, the International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) created a new consensus on Gleason scoring to address prior areas of controversy and architectural patterns that were not accounted for in the original scoring system.3 According to the new consensus, a subset of irregular cribriform glands were re-classified from pattern 3 to pattern 4.

After applying the new 2005 ISUP consensus grading system to radical prostatectomy specimens, Ross et al. observed that no lymph node metastases occurred in Gleason score 3 + 3 = 6 (GS6) prostate cancers.4 All patients who were diagnosed with GS6 cancer with lymph node metastases were upgraded to Gleason score 7 or higher upon re-review of pathology. If the new ISUP consensus on Gleason scoring accurately predicts a subset of patients who do not have lymph node metastases, Gleason scoring takes on an even more important role in prognostication and selection of patients for active surveillance. These prior findings based on patients treated at four large academic centres with specialised genitourinary pathologists have yet to be confirmed in the general population. Therefore, we utilised nationwide population-based Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data to examine the prevalence of lymph node metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancer at radical prostatectomy and its association with demographic and clinicopathological characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used the publicly available SEER 18 database5 to identify prostate cancer patients diagnosed with GS6 on final pathology after radical prostatectomy between 2004 and 2010. Beginning in 2004, SEER registries began recording primary and secondary Gleason pattern in the pathological specimen, whereas in prior years complete Gleason scores were not available. We selected patients who were diagnosed with prostate adenocarcinoma, and excluded those who were diagnosed solely on autopsy or death certificates. We included patients diagnosed with GS6 cancer who had undergone radical prostatectomy and had at least one regional lymph node examined. We identified data on preoperative prostate specific antigen (recorded as highest pretreatment PSA), age at diagnosis, clinical and pathological T stage, year of surgery, race/ethnicity, rural/urban status, and regional SEER registry. Medians were compared using the Kruskall–Wallis test. Differences in distributions of categorical data were compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test when 20% of the cells had an expected cell count of less than five. We constructed a multivariate logistic regression model to examine the association between the presence of lymph node metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 disease with age, pathological T stage, race/ethnicity, urban versus rural, year of diagnosis and preoperative PSA stratified in accord with D’Amico risk criteria as ≥10 and >10 ng/mL. Covariates for the model were selected based on statistical significance on univariate analysis and other variables hypothesised to be relevant to disease staging (e.g., PSA, clinical stage) or potentially related to adoption of the ISUP guidelines (e.g., urban versus rural, race/ethnicity). All data analysis was performed using SEER*Stat version 8.0.1 (seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 385,048 patients with prostate adenocarcinoma were identified, of whom 141,384 were diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancer. Of the patients diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancer, 45,380 had undergone radical prostatectomy, and of those, 21,989 had at least one lymph node examined. Of the patients who had lymph nodes examined, 29 (0.13%) had unknown pathology, and were excluded from the analysis (final n = 21,960). In this nationwide sample, 106 patients (0.48%) had lymph node metastases. The prevalence of lymph node metastasis among patients nationwide was higher than previously reported for academic medical centres by Ross et al. (0.48 versus 0.16%; p < 0.0001).4 Compared to patients who did not undergo lymph node dissection, patients who underwent lymph node dissection had a slightly higher median PSA level (5.3 versus 5.0 ng/mL), more clinical cT2 disease (37 versus 33%), and more pathological pT3/4 disease (6.3 versus 4.7%); the median age at diagnosis was 60 years in both groups.

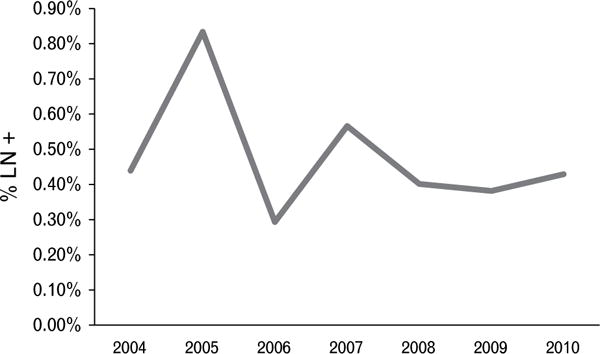

Baseline demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the patients diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancer, with and without positive lymph nodes, are shown in Table 1. Median preoperative PSA was slightly higher for patients with lymph node metastases than those without metastases (5.75 versus 5.30 ng/mL, respectively) although this was not statistically significant. Patients with positive lymph nodes were older than those without positive lymph nodes (62 versus 60 years old, p = 0.03). There were significantly more patients with clinical stage cT2 disease or greater among those with lymph node metastases compared to those without metastases (54% versus 37%, p = 0.0001). Similarly, more patients with lymph node metastases had pathological stage pT3 or pT4 disease than those without metastases (25% versus 6%, p < 0.0001). The prevalence of lymph node metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancer varied over the study period (phet = 0.06) without a clear trend (ptrend = 0.31, Fig. 1). There were no clear differences in the distribution of geographical regions between the two groups.

Table 1.

Men with GS6 prostate adenocarcinoma who underwent radical prostatectomy with ≥1 lymph node examined, 2004–2010

| All Gleason 3+3 n=21,960

|

GS6 negative LN metastases n=21,854

|

GS6 positive LN metastases n=106

|

p value* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | ||

| Median age, years (range) | 60 | (23–91) | 60 | (23–91) | 62 | (45–82) | 0.03† |

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||||||

| <55 | 4,873 | (22.2) | 4,857 | (22.2) | 16 | (15.1) | 0.13‡ |

| 55–59 | 5,511 | (25.1) | 5,485 | (25.1) | 26 | (24.5) | |

| 60–64 | 5,427 | (24.7) | 5,400 | (24.7) | 27 | (25.5) | |

| 65–69 | 4,209 | (19.2) | 4,188 | (19.2) | 21 | (19.8) | |

| ≥70 | 1,940 | (8.8) | 1,924 | (8.8) | 16 | (15.1) | |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 18,527 | (84.4) | 18,443 | (84.4) | 84 | (79.2) | 0.14‡ |

| Black | 2,413 | (11.0) | 2,395 | (11.0) | 18 | (17.0) | |

| Other | 1,020 | (4.6) | 1,016 | (4.6) | <5 | (3.8) | |

| Median PSA, ng/dL (range) | 5.30 | (0.1–98.0) | 5.30 | (0.1–98.0) | 5.75 | (0.2–60.2) | 0.13† |

| Clinical T stage | |||||||

| T1a, T1b | 270 | (1.2) | 267 | (1.2) | <5 | (2.8) | <0.0001§ |

| T1c, T1NOS | 13,200 | (60.1) | 13,158 | (60.2) | 42 | (39.6) | |

| T2 | 8,039 | (36.6) | 7,988 | (36.6) | 51 | (48.1) | |

| T3,T4 | 164 | (0.7) | 158 | (0.7) | 6 | (5.7) | |

| TX | 286 | (1.3) | 282 | (1.3) | <5 | (3.8) | |

| Pathological T stage | |||||||

| T0 | 66 | (0.3) | 66 | (0.3) | 0 | (0) | <0.0001§ |

| T2 | 20,396 | (92.9) | 20,321 | (93.0) | 75 | (70.8) | |

| T3/T4 | 1,393 | (6.3) | 1,367 | (6.3) | 26 | (24.5) | |

| TX | 105 | (0.5) | 100 | (0.5) | 5 | (4.7) | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||||||

| 2004 | 4,099 | (18.7) | 4,081 | (18.7) | 18 | (17.0) | 0.05‡ |

| 2005 | 3,238 | (14.7) | 3,211 | (14.7) | 27 | (25.5) | |

| 2006 | 3,410 | (15.5) | 3,400 | (15.6) | 10 | (9.4) | |

| 2007 | 3,534 | (16.1) | 3,514 | (16.1) | 20 | (18.9) | |

| 2008 | 2,989 | (13.6) | 2,977 | (13.6) | 12 | (11.3) | |

| 2009 | 2,358 | (10.7) | 2,349 | (10.7) | 9 | (8.5) | |

| 2010 | 2,332 | (10.6) | 2,322 | (10.6) | 10 | (9.4) | |

| Rural/urban area | |||||||

| Metropolitan counties | 19,511 | (88.8) | 19,414 | (88.8) | 97 | (91.5) | 0.63§ |

| Urban counties | 2,134 | (9.7) | 2,125 | (9.7) | 9 | (8.5) | |

| Completely rural counties | 308 | (1.4) | 308 | (1.4) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 7 | (0.0) | 7 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | |

| Geographic region | |||||||

| Northeast | 4,150 | (18.9) | 4,123 | (18.9) | 27 | (25.5) | 0.06‡ |

| Midwest | 1,824 | (8.3) | 1,820 | (8.3) | <5 | (3.8) | |

| South | 5,218 | (23.8) | 5,197 | (23.8) | 21 | (19.8) | |

| California | 7,789 | (35.5) | 7,744 | (35.4) | 45 | (42.5) | |

| Other west | 2,979 | (13.6) | 2,970 | (13.6) | 9 | (8.5) | |

LN, lymph node.

p value corresponds to comparison between LN positive and negative groups.

Kruskal–Wallis test.

Chi-square.

Fisher’s exact test.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of GS6 patients with positive LN, 2004–2010.

We constructed a multivariable logistic regression model to examine the association of age, race, preoperative PSA, pathological T stage, and year of diagnosis with the presence of lymph node metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 disease (Table 2). We found that older age, PSA >10 ng/mL, and pT3 or higher stage were all significantly correlated with the presence of positive lymph nodes.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression model for GS6 cancer and positive lymph node(s), 2004–2010

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, per year | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | 0.03 |

| Race | |||

| White | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| Non-white | 1.34 | 0.83–2.16 | 0.23 |

| PSA, ng/mL | |||

| 0–10 | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| >10 | 1.76 | 1.07–2.90 | 0.03 |

| Unknown | 1.76 | 1.06–2.92 | 0.03 |

| Pathological T stage | |||

| T2 | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| T3/T4 | 4.81 | 3.06–7.57 | <0.0001 |

| Tx | 8.04 | 3.20–20.21 | <0.0001 |

| T0 | NA* | NA | NA |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2004–2005 | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| 2006–2010 | 0.69 | 0.47–1.02 | 0.06 |

| Rural/urban | |||

| Metropolitan | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| Non-metropolitan | 0.75 | 0.38–1.48 | 0.40 |

Not estimable because no patients with lymph node metastases. CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

We found that approximately 0.5% of patients nationwide who were diagnosed with GS6 disease had lymph node metastases at the time of radical prostatectomy during 2004–2010. Patients with lymph node metastases were older, had higher PSA levels, and more advanced stage disease. Previous studies from academic medical centres have reported that 0–2.3% of patients diagnosed with GS6 disease had lymph node metastases.4,6 Variations in the prevalence of nodal metastases could be explained by systematic and non-systematic changes in Gleason scoring over time, as well as differences in interpretation of the architectural patterns by pathologists. These discrepancies are increasingly important in patient care with the increased emphasis on active surveillance approaches for patients with low risk, GS6 cancer on biopsy.7,8

In its original formulation, the Gleason scoring system classified prostate adenocarcinomas into five architectural patterns that could be reproducibly recognised and that correlated with outcome in a prostate biopsy population.2,9 After widespread adoption, follow-up studies documented problems with the reproducibility of architectural patterns 1, 2 and 3, particularly in biopsy samples.10 In addition, cribriform patterns, previously characterised as pattern 3, were found to have outcomes more consistent with pattern 4.11 Changes in Gleason grading have been gradually incorporated in a non-systematic fashion in some community and academic practices over many years, and this drift toward assigning higher grades has been referred to as the Will Rogers effect.12 The noted impact of grade drift is that outcomes for both low grade (e.g., GS6) and intermediate grade cancers tend to improve, since cancers of intermediate risk are moved from the low risk category into a high risk category. Disparities in application of Gleason grading as originally described, as well as grade drift, likely account for the differences in outcomes for patients of similar grades between patient series, including differences in the prevalence of lymph node metastases in men diagnosed with GS6 cancer at the time of radical prostatectomy.4,6 Although this drift in Gleason grading was thought to erode the predictive value across the spectrum of Gleason scores, it does have important implications for prognostication of patients with low grade disease in contemporary practice, and by extension, for selection of patients for active surveillance.

The ISUP 2005 consensus conference attempted to address some of the discrepancies in Gleason scoring by incorporating the modifications that had been reported since the grading system gained widespread use. In the study by Ross et al., only 22 of over 14,000 patients (0.16%) treated at four large academic centres between 1975 and 2010 had lymph node metastases at the time of radical prostatectomy, and most cases occurred prior to 2004.4 Re-grading of the 19 available cases using ISUP 2005 consensus criteria resulted in upgrading of all cases, meaning that no case diagnosed as GS6 prostate cancer had lymph node metastases. One important implication of Ross et al.’s study is that it suggests that the ISUP 2005 consensus is an outstanding prognostic tool, particularly for selecting patients with GS6 cancer for active surveillance, since none had lymph node metastases. Since many active surveillance protocols use GS6 as a threshold for selection,13,14 the ability to identify with confidence prostate cancer without associated lymph node metastasis is reassuring for patients and physicians, although sampling issues in biopsy specimens could result in underestimating Gleason score on biopsy.15 Despite this limitation, new methods are being developed to improve accuracy of grade assessment. As new tools are developed for accurately identifying patients with GS6 prostate cancer, such as molecular imaging or gene-based assays,16 acceptance of active surveillance could increase.

The finding of no or low lymph node metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancers is in agreement with the low mortality rates observed in radical prostatectomy series of patients with pathologic GS6 cancer. In a series of 764 patients with detailed pathological characterisation, no patient with GS6 died of prostate cancer regardless of tumour volume.17 At Johns Hopkins, only one death attributable to prostate cancer was recorded in 2159 patients diagnosed with GS6 cancer at radical prostatectomy during 10 years in long-term follow-up, and five (0.23%) of these patients had lymph node metastases.18 The overlap of study periods and medical centre with Ross et al. make it likely that these patients would have been upgraded upon re-review.4

Our study goal assessed the prevalence of lymph node metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 cancers in a nationally representative population, predominantly after the ISUP 2005 consensus recommendations on Gleason grading. An important strength of our study is that the findings provide insights into the practice patterns of scoring GS6 nationally compared to what is observed at large academic medical centres. By using the SEER database, we were able to assess a larger number of patients from more institutions that is more reflective of contemporary national practice patterns. Our study not only demonstrates a higher overall prevalence of lymph node metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 cancers but also reflects a period mostly after the 2005 ISUP consensus statement on Gleason scoring (2004–2010). Our findings suggest that the pathological grading of prostatectomy specimens in a contemporary national sample does not reflect the practice patterns of academic urological pathologists. The temporal relationship in the rate of nodal metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancer in SEER is variable, suggesting that the higher rate of positive lymph nodes reflects more than just a delay in adoption of the ISUP guidelines. It is possible that the differences in the prevalence of nodal metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 prostate cancer could be due to differences in the pathophysiology of disease in patients from community and academic centres. However, re-review of prostate needle biopsies obtained in the community by an experienced genitourinary pathologist resulted in grade reassignment in 14.7% of cases.19 Therefore, a more likely explanation for the higher prevalence of lymph node metastases nationwide is non-uniform adherence to the ISUP 2005 consensus statement on Gleason scoring. The prevalence of positive lymph nodes in patients diagnosed with GS6 cancer could serve as a proxy for assessing adherence to the 2005 ISUP consensus statement on Gleason grading. The distinction between Gleason 3 and 4 disease, and by extension the ability to confidently predict a patient will not develop nodal metastases, is of significant clinical importance for urologists selecting patients for active surveillance or adjuvant hormonal therapy in patients treated with radiation therapy for clinically localised prostate cancer. Thus, variability of adherence to the ISUP guidelines is of interest to both urologists and pathologists alike.

Our study is limited by the small number of patients diagnosed with GS6 cancer who were found to have lymph node metastases at radical prostatectomy. Because many physicians do not perform lymph node dissections in patients with low risk disease, we were limited in the number of patients we could include in our study. This may reduce statistical power to determine other factors associated with lymph node metastases in this cohort of patients. Approximately half of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy underwent lymph node dissection. Patients who underwent lymph node dissection had a slightly higher PSA and slightly more cT2/3/4 and pT3/4 disease. It is possible that selection bias toward performing lymph node dissection in patients with higher PSA levels and more advanced disease resulted in the increased rate of lymph node metastases in patients diagnosed with GS6 disease, however, the differences between the two groups were small and may not be clinically significant. Because this is a retrospective study of SEER, we are not able to obtain review of the pathology of lymph node positive patients to determine if they would have been reclassified using the 2005 ISUP criteria to validate the findings of Ross et al.4 Finally, it is unlikely that Gleason scoring can be made completely uniform and reproducible among pathologists because of grey areas requiring subjective interpretation. For example, in a study of Gleason scoring interpretation of biopsies by a group of academic urological pathologists, interobserver agreement for some traditional Gleason patterns was excellent, whereas for others (i.e., the distinction of poorly formed glands from tangentially sectioned well-formed glands), it was only fair.20

Our analysis of a nationally representative patient population suggests that lymph node metastasis is rare among patients diagnosed with GS6 cancer in contemporary practice. However, the prevalence nationwide is higher than that reported at large academic centres. We submit that the presence of lymph node metastases could be used as a performance marker for accuracy of pathological grading in GS6 prostate cancer in radical prostatectomy specimens.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest and sources of funding: The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Bailar JC, Mellinger GT, Gleason DF. Survival rates of patients with prostatic cancer, tumor stage, and differentiation—preliminary report. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:129–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gleason DF. Classification of prostatic carcinomas. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein JI, Allsbrook WC, Amin MB, et al. The 2005 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason Grading of Prostatic Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1228–42. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173646.99337.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross HM, Kryvenko ON, Cowan JE, et al. Do adenocarcinomas of the prostate with Gleason score (GS) 6 have the potential to metastasize to lymph nodes? Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1346–52. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182556dcd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Research Data + Hurricane Katrina Impacted Louisiana Cases, Nov 2012 Sub (1973–2010 varying) Linked To County Attributes – Total US, 1969–2011 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Surveillance Systems Branch. released April 2013, based on the November 2012 submission. www.seer.cancer.gov.

- 6.Birkhahn M, Penson DF, Cai J, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a Gleason score 6 prostate cancer treated by radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2011;108:660–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganz PA, Barry JM, Burke W, et al. NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: Role of active surveillance in the management of men with localized prostate cancer. NIH Consensus and State-of-the-Science Statements. 2011;28:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esserman LJ, Thompson IM, Reid B. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment in cancer: an opportunity for improvement. JAMA. 2013;310:797–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.108415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gleason DF, Mellinger GT. Prediction of prognosis for prostatic adeno-carcinoma by combined histological grading and clinical staging. J Urol. 1974;111:58–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)59889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allsbrook WC, Mangold KA, Johnson MH, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: urologic pathologists. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:74–80. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.21134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McNeal JE, Villers AA, Redwine EA, et al. Histologic differentiation, cancer volume, and pelvic lymph node metastasis in adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Cancer. 1990;66:1225–33. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900915)66:6<1225::aid-cncr2820660624>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Barrows GH, et al. Prostate cancer and the Will Rogers phenomenon. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1248–53. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klotz L, Zhang L, Lam A, et al. Clinical results of long-term follow-up of a large, active surveillance cohort with localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:126–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter HB, Walsh PC, Landis P, et al. Expectant management of nonpalpable prostate cancer with curative intent: preliminary results. J Urol. 2002;167:1231–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King CR, McNeal JE, Gill H, et al. Reliability of small amounts of cancer in prostate biopsies to reveal pathologic grade. Urology. 2006;67:1229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooperberg M, Simko J, Falzarano S, et al. Development and validation of the biopsy-based genomic prostate score (GPS) as a predictor of high grade or extracapsular prostate cancer to improve patient selection for active surveillance. J Urol. 2013;189:e873. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brooks JD, Tibshirani R, Ferrari M, et al. The impact of tumor volume on outcomes after radical prostatectomy: implications for prostate cancer screening. Open Prostate Cancer J. 2008;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullins JK, Feng Z, Trock BJ, et al. The impact of anatomical radical retropubic prostatectomy on cancer control: the 30-year anniversary. J Urol. 2012;188:2219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brimo F, Schultz L, Epstein JI. The value of mandatory second opinion pathology review of prostate needle biopsy interpretation before radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2010;184:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKenney JK, Simko J, Bonham M, et al. The potential impact of reproducibility of Gleason grading in men with early stage prostate cancer managed by active surveillance: a multi-institutional study. J Urol. 2011;186:465–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]