Abstract

Background

Patients with advanced cancer often experience frequent and prolonged hospitalizations; however factors associated with greater healthcare utilization have not been described. We sought to investigate the relationship between patients’ physical and psychological symptom burden and healthcare utilization.

Methods

We enrolled patients with advanced cancer and unplanned hospitalizations from September 2014-May 2016. Upon admission, we assessed physical (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System [ESAS]) and psychological symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire 4 [PHQ-4]). We examined the relationship between symptom burden and healthcare utilization using linear regression for hospital length of stay (LOS) and Cox regression for time to first unplanned readmission within 90 days. We adjusted all models for age, sex, marital status, comorbidity, education, time since advanced cancer diagnosis, and cancer type.

Results

We enrolled 1,036 of 1,152 (89.9%) consecutive patients approached. Over half reported moderate/severe fatigue, poor well-being, drowsiness, pain, and lack of appetite. Using the PHQ-4, 29% and 28% of patients had depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively. Mean hospital LOS was 6.3 days and 90-day readmission rate was 43.1%. Physical symptoms (ESAS: B=0.06, P<.001), psychological distress (PHQ-4 total: B=0.11, P=.040), and depression symptoms (PHQ-4 depression: B=0.22, P=.017) were associated with longer hospital LOS. Physical (ESAS: HR=1.01, P<.001) and anxiety symptoms (PHQ-4 anxiety: HR=1.06, P=.045) were associated with a higher likelihood for readmission.

Conclusions

Hospitalized patients with advanced cancer experience a high symptom burden, which is significantly associated with prolonged hospitalizations and readmissions. Interventions are needed to address the symptom burden of this population to improve healthcare delivery and utilization.

Keywords: Symptoms, Cancer, Outcomes Research, Hospitalization, Length of Stay, Hospital Readmissions

Introduction

Patients with advanced cancer utilize substantial healthcare resources, and recent trends suggest that rates of healthcare utilization are increasing.1, 2 Hospitalizations account for a significant proportion of this healthcare utilization. Over half of patients with cancer are admitted to the hospital at least once during their last month of life, and nearly 10% experience a hospital readmission during this time.1, 3–6 Importantly, patients with advanced cancer often prefer to avoid hospitalizations, especially near the end of life, yet many still die in the hospital.3, 7–9 Thus, there is a critical need to explore factors that may contribute to the rising healthcare utilization in patients with advanced cancer.

Hospital admissions are not only inconsistent with patients’ preferences, but incur significant costs.10 Rising healthcare costs represent a major challenge in the United States, affecting both patients and providers.11, 12 Medical care for patients in their last year of life accounts for over one-quarter of Medicare spending, and over half of these costs occur in the last 60 days of life.13, 14 Notably, hospitalizations represent the largest component of healthcare spending for patients with cancer.15, 16 Both long hospital stays17 and readmissions cost the healthcare system billions of dollars annually.18 Consequently, programs such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program and value-based purchasing models including accountable care organizations have placed a considerable emphasis on decreasing service utilization, particularly hospital length of stay and readmissions.19–22

Patients with cancer often require hospitalizations for physical symptoms such as pain,23–26 fever,23, 24 dyspnea,24, 25 and fatigue.26 However, much of the existing literature on symptom prevalence and severity in patients with cancer has focused primarily on those in the ambulatory care setting, with very little attention to both the physical and psychological symptom burden of hospitalized patients.27–31 Importantly, the relationship between patients’ physical and psychological symptoms and their hospital length of stay and risk of readmissions is currently unknown. Developing a more comprehensive understanding of the symptom burden of hospitalized patients with advanced cancer and their relationship to patients’ healthcare utilization is an essential first step to enhancing the quality of life and care for this population. By identifying potentially modifiable factors, hospital lengths of stay and readmissions in oncology may be reduced.

In the present study, we prospectively collected patients’ self-reported symptom burden to comprehensively describe the physical and psychological symptoms of hospitalized patients with advanced cancer as well as to explore the relationship between their symptoms and healthcare utilization. We hypothesized that patients with higher physical and psychological symptoms would have longer hospital lengths of stay and greater risk for unplanned readmissions compared with those who report lower symptom burden.

Methods

Study procedures

This study was approved by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board. From 9/2/2014 to 5/6/2016, we enrolled 1,036 patients with advanced cancer with an unplanned hospital admission at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in a longitudinal cohort study. We identified and recruited consecutive patients who had an unplanned hospital admission (index hospitalization) during the study period by screening the daily inpatient oncology census. Each participant contributed one unique hospitalization. A research assistant obtained written, informed consent from eligible patients on the first weekday following admission (within 2-5 days of hospitalization). Following consent, participants completed a symptom burden questionnaire.

Participants

Patients were eligible for study participation if they were age 18 or older and admitted to MGH with known diagnosis of advanced cancer. We defined patients with advanced cancer as those not being treated with curative intent. We identified patients not being treated with curative intent based on the chemotherapy order entry treatment intent designation (palliative vs. curative), or based on documentation in the oncology clinic notes for those not receiving chemotherapy. Study participants also had to be able to read and respond to study questionnaires in English or with minimal assistance from an interpreter. We excluded patients with elective or planned hospital admissions, defined as hospitalizations for chemotherapy administration, scheduled surgical procedures, or chemotherapy desensitization. We also excluded patients with leukemia and those admitted for stem cell transplantation.

Study Measures

Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors

Each patient registering for care at MGH is required to provide demographic information, which is documented in the demographics section of the electronic health record (EHR). We reviewed the demographics section of the EHR to obtain participants’ date of birth, sex, race, relationship status, education, and religion. We also reviewed patients’ oncology clinic notes in the EHR to determine the Charlson Comorbidity Index, date of diagnosis with advanced cancer, and cancer type.

Patient-Reported Symptom Burden

We used a modified version of the self-administered revised Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS-r) to assess patients’ symptoms.32 The ESAS-r assesses pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, appetite, dyspnea, depression, anxiety, and well-being over the previous 24-hours. We also included constipation, as this is a highly prevalent symptom in patients with advanced cancer.33 Individual symptoms are scored on a scale of 0-10 (0 reflecting absence of the symptom and 10 reflecting the worst possible severity). Consistent with prior research, we categorized the severity of ESAS scores as none (0), mild (1-3), moderate (4-6), and severe (7-10).34 We computed the composite ESAS physical and total symptom variables that include summated scores of patients’ physical (pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, appetite, dyspnea, constipation) and total symptoms (pain, fatigue, drowsiness, nausea, appetite, dyspnea, depression, anxiety, wellbeing, constipation). The ESAS-physical and total symptom scores are well-validated and have been utilized previously in the oncology setting, with minimal clinically important differences of three points for each of these composite scores.32, 35

To assess patients’ psychological symptoms, we used the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4).36, 37 The PHQ-4 is a 4-item tool that contains two 2-item subscales assessing depression and anxiety symptoms. Both subscales and the composite PHQ-4 can also be evaluated continuously with higher scores indicating worse psychological distress.36 Scores on each subscale range from 0 to 6, with a score of 3 or greater denoting clinically significant depression or anxiety.36 We added the PHQ-4 to the study questionnaires on 11/15/2014 to have a validated measure specifically for psychological distress rather than the single depression and anxiety items of the ESAS-r.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of the study was hospital length of stay. We defined hospital length of stay as the number of days from hospital admission to hospital discharge. The secondary outcome focused on unplanned hospital readmissions. To account for mortality, as patients who die after their index hospitalization have less time at risk for readmission, we used time to first unplanned admission within 90-days of hospital discharge as the outcome measure. We defined time to first unplanned readmission within 90-days as the number of days from hospital discharge to first unplanned readmission within 90-days. We censored patients without a readmission at their 90-day post-discharge date and those who died within 90-days at their death date. Additionally, we created a composite dichotomous outcome categorizing patients as dead and/or readmitted within 90-days (yes vs. no) vs. those alive and with no readmissions within 90-days to account further for early mortality.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to evaluate the frequencies, means, and standard deviations (SDs) for participants’ characteristics and symptom burden. To investigate the relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and hospital length of stay, we computed linear regression models adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index), time since advanced cancer diagnosis, and cancer type. Given collinearity between physical and psychological symptoms, we created separate models for each of the following: PHQ-4 total score (total psychological distress), PHQ-4 depression subscale, PHQ-4 anxiety subscale, ESAS physical, ESAS total, ESAS depression, and ESAS anxiety. We used Cox proportional hazards regression models adjusted for the same variables described above to assess the relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and time to readmission within 90-days. Lastly, we used logistic regression models adjusted for the same variables described above to assess the relationship between physical and psychological symptoms and the odds of death or readmission within 90-days.

With a sample size of 1,000 patients, the study has >95% power to detect 0.2 difference in hospital length of stay in days for a 1 point increase in symptom burden as measured by the ESAS and a 1 point increase in psychological distress as measured by the PHQ-4, with a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Less than 1% of patients had missing data for each individual symptom, precluding the need for missing data imputations. All reported P values are two-sided with a P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. We used Stata 9.3 for all statistical analyses.

Results

Participant Sample

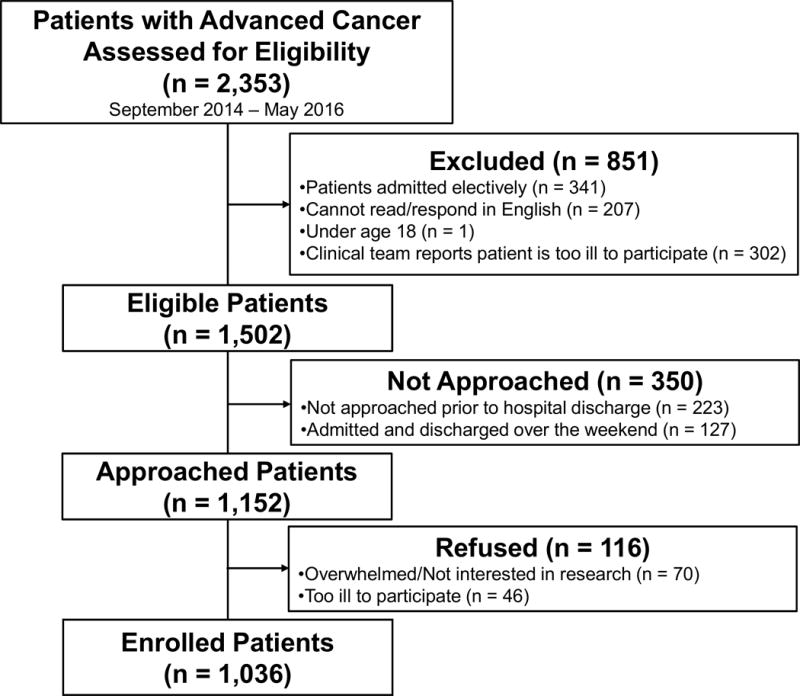

We screened a total of 2,353 patients for eligibility (Figure 1). We approached 1,152 eligible patients and enrolled 1,036 (89.9%) participants. Participants (mean age = 63.4 ± SD 12.9 years) were primarily white (92.4%), married (66.2%), and educated beyond high school (60.3%) (Table 1). Gastrointestinal cancers were the most common cancer type (32.0%), and participants had a mean time since diagnosis of advanced cancer of 510.01 days (SD=722.66). Participants had a mean hospital length of stay of 6.26 days (SD=4.82). The 90-day readmission rate was 43.1%, and the 90-day death rate was 41.6%. Nearly two-thirds of participants (65.0%) died or were readmitted within 90-days.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

SD = standard deviation

| Patient Characteristics | No. (%) (n = 1,036) |

|---|---|

| Age - mean (SD) | 63.38 (12.86) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 512 (49.4) |

| Male | 524 (50.6) |

| Race | |

| White | 957 (92.4) |

| African American | 35 (3.4) |

| Asian | 21 (2.0) |

| Hispanic | 21 (2.0) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1 (0.1) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1) |

| Relationship status | |

| Married | 686 (66.2) |

| Single | 154 (14.9) |

| Divorced | 115 (11.1) |

| Widowed | 81 (7.8) |

| Education | |

| High School and Below | 326 (31.5) |

| Beyond High School | 625 (60.3) |

| Declined | 85 (8.2) |

| Religion | |

| Catholic | 515 (49.7) |

| Christian, Non-Catholic | 322 (31.1) |

| None | 130 (12.5) |

| Jewish | 54 (5.2) |

| Muslim | 6 (0.6) |

| Other | 9 (0.9) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index - mean (SD) | 0.89 (1.29) |

| Cancer type | |

| Gastrointestinal | 332 (32.0) |

| Lung | 190 (18.3) |

| Genitourinary | 113 (10.9) |

| Melanoma | 90 (8.7) |

| Breast | 75 (7.2) |

| Lymphoma | 64 (6.2) |

| Head and Neck | 56 (5.4) |

| Gynecologic | 52 (5.0) |

| Sarcoma | 50 (4.8) |

| Cancer of unknown primary | 14 (1.4) |

Patient-Reported Symptom Burden

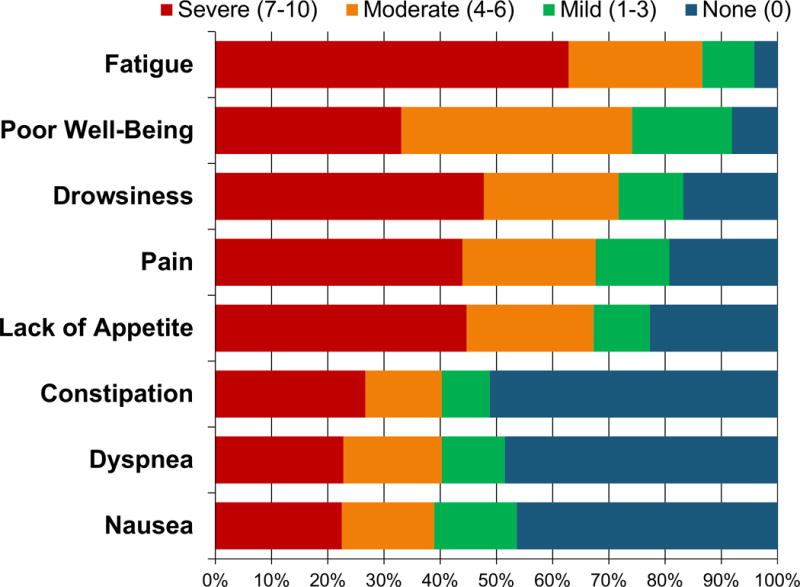

Figure 2 depicts the severity of symptom burden in hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Over half of patients reported moderate/severe fatigue (86.7%), poor well-being (74.2%) drowsiness (71.7%), pain (67.7%), and lack of appetite (67.3%). Of the 10 ESAS symptoms we evaluated, patients reported experiencing a mean of 5.76 (SD=2.38) moderate/severe symptoms. In our sample, only 17 (1.7%) reported experiencing no moderate/severe symptoms. Over one-fourth of participants had clinically significant depression (28.8%) and anxiety (28.0%) symptoms based on their PHQ-4 scores.

Figure 2.

Physical Symptoms in Hospitalized Patients with Advanced Cancer

The Relationship between Symptom Burden and Hospital Length of Stay

Table 2 depicts the relationship between patients’ physical and psychological symptoms with their hospital length of stay after controlling for age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities, time since advanced cancer diagnosis, and cancer type. Patients’ physical symptoms (ESAS-physical: B=0.06, 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.09, SE=0.01, P<0.001)] and total symptom burden (ESAS-total: B=0.05, 95% CI: 0.03 to 0.06, SE=0.01, P<0.001) were both significantly associated with longer hospital length of stay. Additionally, patients’ total psychological distress (PHQ-4 total: B=0.11, 95% CI: 0.005 to 0.21, SE=0.05, P=0.040), PHQ-4 depression scores (B=0.22, 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.40, SE=0.09, P=0.017), and ESAS depression scores (B=0.10, 95% CI: 0.01 to 0.19, SE=0.05, P=0.034) were also associated with longer hospital length of stay. However, patient-reported anxiety symptoms were not related to length of hospitalization (PHQ-4 anxiety: B=0.12, 95% CI: −0.06 to 0.30, SE=0.09, P=0.190; ESAS anxiety: B=0.09, 95% CI: −0.004 to 0.18, SE=0.05, P=0.061).

Table 2. Relationship between Physical and Psychological Symptoms and Hospital Length of Stay.

B = unstandardized coefficient, CI = confidence interval, SE = standard error, PHQ-4 = Patient Health Questionnaire-4, ESAS = Edmonton Symptom Assessment System

| Hospital Length of Stay | B | 95% CI | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESAS Physical* | 0.064 | 0.042 to 0.085 | 0.011 | <0.001 |

| ESAS Total* | 0.045 | 0.029 to 0.062 | 0.008 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-4 Total* | 0.107 | 0.005 to 0.209 | 0.052 | 0.040 |

| PHQ-4 Depression* | 0.222 | 0.039 to 0.404 | 0.093 | 0.017 |

| PHQ-4 Anxiety* | 0.118 | −0.059 to 0.296 | 0.090 | 0.190 |

All models adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities, time since incurable cancer diagnosis, and cancer type.

The Relationship between Symptom Burden and Unplanned Hospital Readmissions

Table 3 depicts the relationship between patients’ physical and psychological symptoms and their unplanned hospital readmissions within 90-days. Patients’ physical symptoms (ESAS physical: HR=1.01, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.02, SE=0.004, P<0.001), total symptom burden (ESAS total: HR=1.01, 95% CI: 1.00 to 1.02, SE=0.003, P<0.001), and PHQ-4 anxiety symptoms (HR=1.06, 95% CI: 1.00 to 1.12, SE=0.03, P=0.045) were all significantly associated with higher risk of unplanned hospital readmission within 90-days. Patient-reported depression symptoms (PHQ-4 depression: HR=1.04, 95% CI: 0.98 to 1.10, SE=0.03, P=0.219; ESAS depression: HR=1.01, 95% CI: 0.98 to 1.04, SE=0.02, P=0.672) and ESAS anxiety scores (HR=1.02, 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.05, SE=0.02, P=0.118) were not related to the risk of unplanned hospital readmissions during this period.

Table 3. Relationship between Physical and Psychological Symptoms and Time to Readmission within 90-Days.

HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, SE = standard error, PHQ-4 = Patient Health Questionnaire-4, ESAS = Edmonton Symptom Assessment System

| Time to Readmission within 90-Days | HR | 95% CI | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESAS Physical* | 1.013 | 1.006 to 1.021 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| ESAS Total* | 1.010 | 1.004 to 1.015 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-4 Total* | 1.030 | 0.997 to 1.064 | 0.016 | 0.072 |

| PHQ-4 Depression* | 1.038 | 0.978 to 1.101 | 0.030 | 0.219 |

| PHQ-4 Anxiety* | 1.059 | 1.001 to 1.119 | 0.028 | 0.045 |

All models adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities, time since incurable cancer diagnosis, and cancer type.

Additionally, patients’ physical symptoms (ESAS physical: OR=1.03, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.04, SE=0.01, P<0.001), total symptom burden (ESAS total: OR=1.02, 1.01 to 1.03, SE=0.004, P<0.001), total psychological distress (PHQ4- total: OR=1.09, 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.14, SE=0.02, P<0.001), depression symptoms (PHQ-4 depression: OR=1.18, 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.29, SE=0.04, P<0.001; ESAS depression: OR=1.05, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.10, SE=0.02, P=0.013), and PHQ-4 anxiety symptoms (OR=1.11, 95% CI: 1.02 to 1.20, SE=0.04, P=0.012), were all significantly associated with higher likelihood of death or readmission within 90-days (Table 4).

Table 4. Relationship between Physical and Psychological Symptoms and Death or Readmission within 90-Days.

OR = odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, SE = standard error, PHQ-4 = Patient Health Questionnaire-4, ESAS = Edmonton Symptom Assessment System

| Death or Readmission within 90-Days | OR | 95% CI | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESAS Physical* | 1.031 | 1.020 to 1.041 | 0.005 | <0.001 |

| ESAS Total* | 1.023 | 1.015 to 1.031 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-4 Total* | 1.090 | 1.038 to 1.144 | 0.025 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-4 Depression* | 1.182 | 1.083 to 1.290 | 0.045 | <0.001 |

| PHQ-4 Anxiety* | 1.110 | 1.023 to 1.204 | 0.042 | 0.012 |

All models adjusted for age, sex, marital status, education level, comorbidities, time since incurable cancer diagnosis, and cancer type.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that hospitalized patients with advanced cancer experience an immense physical and psychological symptom burden, with over half reporting moderate to severe physical symptoms such as fatigue, pain, drowsiness, and poor appetite. Notably, more than one quarter also reported clinically significant depression and anxiety symptoms. Moreover, hospitalized patients’ physical and psychological symptoms were significantly associated with longer hospital length of stay and greater risk for unplanned hospital readmissions within 90 days. Collectively, these findings underscore the prevalence and severity of symptoms that hospitalized patients with cancer experience as well as illustrate the patterns of utilization within this highly symptomatic population.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the relationship between patients’ self-reported physical symptoms and healthcare utilization among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Patients’ physical symptom burden was significantly associated with both their hospital length of stay as well as their risk of unplanned hospital readmission within 90-days. As prior studies have shown that patients’ symptoms may result in hospital admissions,23, 24 our investigation provides novel insights to help clinicians and policymakers critically assess the potential contribution of uncontrolled symptoms to excessive and costly cancer care. Interventions such as symptom monitoring and the integration of patient-reported outcomes into routine processes of care are promising strategies to reduce symptom burden and enhance patient-reported outcomes.38, 39 Future research should also focus on testing the potential efficacy of such interventions on reducing patients’ use of healthcare services.

Interestingly, we also observed that patients’ psychological symptoms were significantly associated with their hospital length of stay and risk of unplanned readmissions. While studies of patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary disease have shown an association between psychological distress and increased use of healthcare services,40–43 no prior investigations have explored this relationship among hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Given the proportion of patients with depression and anxiety symptoms in this sample, these findings are noteworthy. Possible explanations for the relationship between psychological distress and increased healthcare utilization include the tendency for individuals with psychological distress to present with multiple physical complaints.44–46 In addition, depression and anxiety symptoms may influence patients’ health behaviors, including treatment non-adherence, which in turn can increase the risk for hospitalizations.47 Notably, we observed differences in the relationship between anxiety and readmissions, depending on the use of the ESAS or PHQ-4 assessments of anxiety. ESAS-anxiety is a single-item measure and may lack the sensitivity for significant anxiety symptoms when compared to the PHQ-4, a well-validated, multi-item tool for detecting anxiety and depression. Future studies are needed to fully explore the potential mechanisms of the associations we found between patients’ psychological symptoms and their use of healthcare services. However, our findings suggest that hospitalized patients with advanced cancer who experience clinically significant psychological distress represent a highly vulnerable population at risk for prolonged hospitalizations and unplanned readmissions. Consequently, strategies to screen hospitalized patients for psychological distress and provide them with adequate psychological resources should be tested in the future to improve the quality of their care.

Our work represents the largest study to date highlighting the immense symptom burden of hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Importantly, patients’ symptoms represent a potentially modifiable risk factor that, if properly addressed, may improve healthcare quality and delivery. In fact, studies have shown that targeted interventions aimed at improving symptom management can enhance patient-reported outcomes.38, 48, 49 However, most of these efforts are targeting the symptom burden of patients with cancer in the ambulatory care setting.38, 48, 49 Hospitalized patients with advanced cancer often experience a higher symptom burden than those in the outpatient setting,30, 31 and thus there is a critical need to determine the efficacy of supportive care interventions in this population to reduce symptom burden and prevent excess use of healthcare services.

Several limitations of this study warrant discussion. First, we performed the study at a single, tertiary care site in a patient sample with limited socioeconomic diversity, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other, more diverse populations or to patients in other geographic areas. Second, it is possible that differences in illness severity and other factors could confound the relationship between symptom burden and healthcare utilization. Nonetheless, patients’ symptom burden remained a significant predictor of healthcare use after adjusting for potential confounders including comorbidity, cancer type, and time since the diagnosis of advanced cancer. Third, while we report the association between symptom burden and higher healthcare utilization, we are unable to determine the mechanism of this association or comment on causality. Finally, we examined the relationship between patients’ symptoms collected within five days of their admission, but we lack information regarding changes in symptom severity during hospitalization. Future research should include daily symptom assessments to understand better how patients’ symptom trajectories relate to their use of healthcare services.

In summary, hospitalized patients with advanced cancer experience high rates of uncontrolled physical and psychological symptoms that are significantly associated with prolonged hospitalizations and higher risk for unplanned hospital readmissions. Most, if not all, of the symptoms identified are treatable with intensive supportive care measures, which can be feasibly implemented, especially during hospital admissions. These findings highlight the critical need to monitor and address the physical and psychological symptom burden of hospitalized patients with advanced cancer. Interventions to identify and treat symptomatic patients hold great potential for improving patients’ experience with their illness, enhancing their quality of life, and reducing their healthcare utilization.

Precis.

In this study, we demonstrated that hospitalized patients with advanced cancer experience a high symptom burden, with over half reporting moderate to severe fatigue, pain, drowsiness, and poor appetite. We found that patients’ physical and psychological symptoms are associated with longer hospital length of stay and greater risk for unplanned hospital readmissions.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: NCI K24 CA181253 (Temel), MGH Cancer Center Funds (Temel), Scullen Center for Cancer Data Analysis (Hochberg)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. All were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All provided final approval of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Previous presentations: Previously presented at the 2016 ASCO Palliative Care in Oncology Symposium in San Francisco, CA and the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting in Chicago, IL.

References

- 1.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho TH, Barbera L, Saskin R, Lu H, Neville BA, Earle CC. Trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in the universal health care system of Ontario, Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1587–1591. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.9897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:287–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR, et al. Comparison of Site of Death, Health Care Utilization, and Hospital Expenditures for Patients Dying With Cancer in 7 Developed Countries. JAMA. 2016;315:272–283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, Neville BA, Weeks JC, Ayanian JZ. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3860–3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Stukel TA, Skinner JS, Sharp SM, Bronner KK. Use of hospitals, physician visits, and hospice care during last six months of life among cohorts loyal to highly respected hospitals in the United States. BMJ. 2004;328:607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7440.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pritchard RS, Fisher ES, Teno JM, et al. Influence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Risks and Outcomes of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beccaro M, Costantini M, Giorgi Rossi P, et al. Actual and preferred place of death of cancer patients. Results from the Italian survey of the dying of cancer (ISDOC) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:412–416. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeurkar N, Farrington S, Craig TR, et al. Which hospice patients with cancer are able to die in the setting of their choice? Results of a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2783–2787. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Teno JM, Fisher ES, Hamel MB, Coppola K, Dawson NV. Medical care inconsistent with patients’ treatment goals: association with 1-year Medicare resource use and survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:496–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010–2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nipp RD, Zullig LL, Samsa G, et al. Identifying cancer patients who alter care or lifestyle due to treatment-related financial distress. Psychooncology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pon.3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lubitz JD, Riley GF. Trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1092–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304153281506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riley GF, Lubitz JD. Long-term trends in Medicare payments in the last year of life. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:565–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:630–641. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brooks GA, Li L, Uno H, Hassett MJ, Landon BE, Schrag D. Acute hospital care is the chief driver of regional spending variation in Medicare patients with advanced cancer. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33:1793–1800. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stitzenberg KB, Chang Y, Smith AB, Nielsen ME. Exploring the burden of inpatient readmissions after major cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:455–464. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.5938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albright HW, Moreno M, Feeley TW, et al. The implications of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act on cancer care delivery. Cancer. 2011;117:1564–1574. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, Observation, and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1543–1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McWilliams JM, Landon BE, Chernew ME. Changes in health care spending and quality for Medicare beneficiaries associated with a commercial ACO contract. JAMA. 2013;310:829–836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Landon BE, Schwartz AL. Performance differences in year 1 of pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1927–1936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1414929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks GA, Abrams TA, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Identification of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in patients with GI cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:496–503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.52.4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Numico G, Cristofano A, Mozzicafreddo A, et al. Hospital admission of cancer patients: avoidable practice or necessary care? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbera L, Paszat L, Qiu F. End-of-life care in lung cancer patients in Ontario: aggressiveness of care in the population and a description of hospital admissions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Modonesi C, Scarpi E, Maltoni M, et al. Impact of palliative care unit admission on symptom control evaluated by the edmonton symptom assessment system. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, et al. High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2297–2304. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, de Haes HC, Voest EE, de Graeff A. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. Symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress in a cancer population. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:183–189. doi: 10.1007/BF00435383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang VT, Hwang SS, Feuerman M. Validation of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale. Cancer. 2000;88:2164–2171. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000501)88:9<2164::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhondali W, Nguyen L, Palmer L, Kang DH, Hui D, Bruera E. Self-reported constipation in patients with advanced cancer: a preliminary report. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selby D, Cascella A, Gardiner K, et al. A single set of numerical cutpoints to define moderate and severe symptoms for the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hui D, Shamieh O, Paiva CE, et al. Minimal Clinically Important Difference in the Physical, Emotional, and Total Symptom Distress Scores of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowe B, Wahl I, Rose M, et al. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2010;122:86–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom Monitoring With Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Cancer Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1480–1501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coventry PA, Gemmell I, Todd CJ. Psychosocial risk factors for hospital readmission in COPD patients on early discharge services: a cohort study. BMC Pulm Med. 2011;11:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-11-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reese RL, Freedland KE, Steinmeyer BC, Rich MW, Rackley JW, Carney RM. Depression and rehospitalization following acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:626–633. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levine JB, Covino NA, Slack WV, et al. Psychological predictors of subsequent medical care among patients hospitalized with cardiac disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1996;16:109–116. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Volz A, Schmid JP, Zwahlen M, Kohls S, Saner H, Barth J. Predictors of readmission and health related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: a comparison of different psychosocial aspects. J Behav Med. 2011;34:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1329–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care. Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:774–779. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prieto JM, Blanch J, Atala J, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and impact on hospital length of stay among hematologic cancer patients receiving stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1907–1917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101–2107. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berry DL, Hong F, Halpenny B, et al. Electronic self-report assessment for cancer and self-care support: results of a multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:199–205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.48.6662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strasser F, Blum D, von Moos R, et al. The effect of real-time electronic monitoring of patient-reported symptoms and clinical syndromes in outpatient workflow of medical oncologists: E-MOSAIC, a multicenter cluster-randomized phase III study (SAKK 95/06) Ann Oncol. 2016;27:324–332. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]