Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Although education is one of the most substantial needs of patients that should be taught by nurses and midwives, it is not clearly defined through the hidden curriculum in students’ teaching programs. The aim of this study was to explore the patient education through the hidden curriculum in the perspectives of nursing and midwifery students.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A qualitative, content analysis study was performed and twenty nursing and midwifery students were interviewed. Data were collected using face-to-face semi-structured interviews and analyzed using conventional content analysis approach.

RESULTS:

Students’ perception of the hidden curriculum in patient education emerged in three main themes concerning: (1) interactions, (2) teaching and learning opportunities, and (3) reflective evaluation.

CONCLUSIONS:

The hidden curriculum in patient education can be transferred as interactions between professors, students, nurses, doctors, and also patients who are rooted from paying attention to the human dimension of the patient, avoiding the materialistic treatment of the patient and treating the patient with dignity. Educational policies and students’ assignments should be designed based on the patient's educational goals and the goal of evaluation has to be presented to the students clearly.

Keywords: Content analysis, hidden curriculum, patient education

Introduction

Education is one of the fundamental necessities of patients and it improves their health status, increases patient satisfaction, and reduces readmission to the hospital.[1,2] Patient education makes up 70% of the care given by nurses,[3,4] and yet is one of the ethical responsibilities of nurses and midwives.[5] The results of studies in the developed countries show that one of the five factors of their success in patient education programs is organizing training as a care.[6] A study in Iran indicated that the patient education has not been satisfactory and the authors have stressed the necessity of enhancing nurses’ awareness on the importance of patient education.[7] Lack of knowledge, lack of communication skills, and heavy workload were main barriers to patient education from the perspectives of nursing students in Iran.[8]

Taking into consideration, the studies carried out on patient education, it is of importance to explore the process of patient education based on what nurses and midwives have learned during their studies as nursing and midwifery students. Besides, studies have shown that students’ learning is not limited to the formal/official curriculum, but they learn beyond what is taught as by feeling, by trial and error, and even in tests that the students take in schools which is known as the hidden curriculum.[9] As a matter of fact, the apparent curriculum should be taught formally as a subject matter and the null curriculum refers to what is not being taught.[9,10,11,12] Many studies emphasized the part of teacher's information of dimensions of the hidden curriculum such as interpersonal relationships, teacher's personality traits, teacher's moral considerations, error management, and the teacher's teaching methods and performance.[13,14,15] So far, various aspects of the hidden curriculum have been introduced. Portelli has divided the hidden curriculum into four categories: (1) expected informal messages, (2) not intended learning outcomes, (3) informal messages of the school structure, and (4) created programs by students.[16] Anderson considers three dimensions for hidden curriculum: (1) knowledge of teaching based on social features, (2) effect of the situation where informal education is presented, and (3) unstated rules.[17] Ahola knows four of principal aspects the hidden curriculum as “learning how to learn; learning a profession; learning to be an expert; and learning the game.”[18] Alikhani introduced the hidden curriculum as the following dimensions: (a) how people interact in school; (b) organizational structure, and (c) the physical constitution of the school and classroom.[19] In these studies, a single definition of the hidden curriculum is not stated and the authors categorized it by specific topics. On the other hand, none of the studies as yet mentioned the role of hidden curriculum in transferring skills to educate patients.

Due to some incongruity between the nursing training and their educational goals,[20] the need for change and improvement of training programs, especially in the hidden curriculum has been stressed.[21] Given the importance of patient education and the position of nurses and midwives in it, attention to the students’ attitude toward educating patients is clearly understood. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to explore nursing and midwifery students’ perception of hidden curriculum regarding patient education.

Materials and Methods

This qualitative study was carried out using the conventional content analysis approach. The content analysis is a suitable method for reaching in-depth information and valid results in content-based data.[22]

The study participants comprise nursing and midwifery students of Bushehr University of Medical Sciences in the South of Iran. Purposive sampling and convenience sampling were utilized to select the participants. Only the candidates who had passed at least one period of apprenticeship in a hospital setting were allowed to participate in the study; they also should be willing to take part in interviews and share their views, experiences, and feelings. The first interview was conducted with a very expressive nursing student in the seventh semester. The research setting of the study was at Bushehr University of Medical Sciences in the South of Iran, and the venues of interviews such as dormitory, university classrooms, or hospital meeting rooms were decided by the entrants. The study participants included twenty students (14 nursing and 6 midwifery) of Bushehr University of Medical Sciences enrolled in the 4th to the 8th semesters (3 students in semester 4, 2 in semester 5, 4 in semester 6, 6 in semester 7, and 5 in semester 8).

Data were collected from December 2014 to May 2015. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with the sample group. Before starting the interview, the researcher established a proper communication with participants; after that the purpose of the study, confidentiality of the information, and the recording of the interview were explained to them and obtaining their written consent to conduct and record the interviews. The method of data collection in the study was face-to-face semi-structured interviews done in a private place which was convenient to the participants. During the interview, the participants were asked to describe specific experiences and perception with regard to how to educate their patients in the clinical and health settings. The objective was for each to consider specific situational-clinical or health factors that served to promote or constrain their interactions with patients and patient education. The guiding questions for the interviews were as follows: “On what principles and resources do you teach to your patients? How have you learned these principles and resources? Where have you learned these principles and resources? Please provide an example. What facilitates the process of patient education?” These primary interview questions were developed as a result of first interviews and then were scrutinized by all research teams involved in the study and as a result, modifications were made and probing questions were created. Each interview lasted between 40 and 50 min. After 17 interviews, the responses were repeated and no new data were added to previous interviews; nonetheless three additional interviews with different participants were undertaken to validate that no additional content was generated, hence data saturation was determined and interviews were concluded.

Data analysis was performed using the constant comparison technique and the Graneheim and Lundman's qualitative content analysis approach. Accordingly, we took the following five steps to analyze the data: (1) transcription of the interviews right after the end of interview sessions; (2) reading the transcription of the interviews for a better understanding of the contents; (3) identifying meaning units and primary codes; (4) categorizing similar codes into main categories; and 5 identifying the main themes of the categories.[23] The primary analysis was performed by the first researcher. All of the interviews were recorded with a digital voice recorder and then were listened carefully, transcribed and typed word per word at the first occasion to keep relation with the data and the participants’ feelings. Afterward, the researcher reviewed the text and made notes of her first impressions. As this process continued, code labels emerged that were reflective of more than one key thought. These often came directly from the text and produced the initial coding scheme. Two experts in qualitative analysis and subject matter (MR and MrY) performed the transcript peer review and confirmed that 85% of codes and themes were accurate; in the case of discrepancies and different interpretations among researchers, several panels made up of the entire research team examined the coding process to agree on a final version.

To increase the trustworthiness and rigor of data, the researchers devoted time to collect the information. Credibility was established along prolonged engagement with participants and the data, member checking, peer checking, external checking, and constant comparison. The research team members had regular meetings and reviewed the process analysis; additionally, passed the initial codes that came out from each interview to the concerned participants and they approved the emerged codes. We also shared the results of the study with professors and our research colleagues to gain a better understanding of the outcome.[24,25] The researcher also attempted to provide a complete and detailed report of the research. To increase the transferability of the report, the investigators shared the categorization of the data with students in other universities and they also confirmed the link between the findings and their own experiences.

The Research Committee of the Bushehr University of Medical Sciences approved this study and the investigators collected the data on its approval. All study participants were oriented with regard to the objectives of this paper and they were assured that they would remain anonymous. Furthermore, only a part of their one-on-one dialog will be cited and they can leave the study whenever they want without any consequences. Interview transcriptions and research records will be kept confidential. All participants gave both their oral and written consent for their participation in the study.

Results

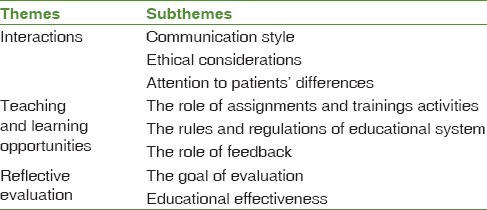

This qualitative study included twenty nursing and midwifery student participants. The age of participants varied between 22- and 26-year-old. The study population comprised 16 females and 4 males. Participants of the study included 6 bachelor midwifery students and 14 nursing students. Three themes of interactions, teaching and learning opportunities, and reflective evaluation were extracted from the interview transcription as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Emerged subthemes and themes about perspectives of nursing and midwifery students regarding role of hidden curriculum in patient education

Theme I: Interactions

Students noted that types of interaction and form of communication between patients and group of teachers, students, nurses, and doctors had a great influence on them as part of the hidden curriculum. During the one-on-one dialog, the students stressed the relevance of attention to the interaction and communication styles of the professors/instructors in their relation with the patients. They also reported the essentiality of ethical considerations during instruction and paid attention to individual differences and learning motivations. With these, three subthemes emerged from the interactions with patients.

Communication style

The student's communication style was defined as mutual communication and socialization and the process of transferring health messages to the patients to change a health behavior. The participants mentioned the function of effective communication in enhancing the quality of teaching. The students mainly focused on their learning role models like their instructors, hospital nurses, and doctors. Likewise, health professionals can only possibly transfer medical information and materials to the students when they have communicated very well with them and believing in their social positions. One of the Midwifery students who is 25-year-old notes: “When a pregnant woman was suffering from pain, hospital staff or instructors used effective respiration (focusing on breathing) or distraction methods. When the patient listened to them, she felt the pain alleviates; this experience and the use of distraction methods were etched in my memory,” she adds.

Ethical considerations

Paying attention to human dimension of the patient by professors, nurses, or even doctors, avoiding materialistic treatment of the patient, treating the patient with dignity, respecting the patient's privacy, and gaining the patient's trust were considered as the ethical considerations. In regard to patient education, the students believe they can have their best performance when they observe the ethical considerations and treat the patients with dignity and respect.

A 24-year-old male participant adds: “We had a professor who would very patiently answer the patients’ questions and if he needed any information he would consult a doctor or the patients’ medical profile. He would not even ignore the patient's relatives and for these reasons, he was so popular.”

Attention to patients’ differences

The participants pointed out to consider the following: patients’ differences and motivations in learning, their cultural and social backgrounds, understanding patient's educational needs, appropriate education based on the diagnosis of the illness, and response to the patients’ questions like questions to find out what information the patient needs to present the required instructions, and flexibility in the patients’ education curriculum to suit every patient's needs. An example is trying to explain nursing care and the nature of the disease in simple terms based on each patient's level of education and tolerance.

Theme II: Teaching and learning opportunities

The participants defined teaching and learning opportunities as: the privileges presented to them by professors, hospital personnel, medical practitioners, patients, the theoretical and practical assignments and instructions, the comprehension of the educational requirements, and the rules of the educational system.

The role of assignments and training activities

This subtheme involves assignments in clinical settings connecting to pedagogic objectives, time to finish the assignments, and clinical training to acquire the necessary skills. They believed that the assignments and training designed by the nursing instructors were only effective when they were goal-driven or within the framework of the presented lessons. A 24-year-old male participant notes: “During our clinical training, sometimes our instructor asks us to discuss what we have done to our patients. He encourages us to ask any questions we have in mind. Today's question could be used as tomorrow's assignment so we can learn by practice.”

The rules and regulations of educational system

The policies of the nursing and midwifery faculty have a crucial part in the training and instruction of students in patient education. From the participants’ viewpoints, evaluating every university may entail various instructional criteria. These criteria depend on the approaches set by the instructional institution emphasizing on specific contents such as hospital policies that highlight patient education or certain types of patients’ problems, resolution of problems, educational policies and professors’ teaching styles, and educational personnel of these institutions. A 23-year-old female midwifery student says: “It is vital that professors teach the fundamental materials practically. Professors often instruct certain materials that are in contrast with the practices of hospital staff management. There are usually some discrepancies between the theoretical and practical aspects.”

Theme III: Reflective evaluation

From the participants’ views, the role of evaluation in teaching is very prominent and effective and it reveals the results of a course, and both the professor and students will find out if they have achieved their objectives. They also discover the gaps and difficult tasks during the training course so they can address all of them, accordingly.

The role of feedback

The participants’ statements that influenced their learning are as follows: the type of feedback they receive from the instructions given to the patients, the encouragement they get for their good performance, and the punishment they obtain for their poor performance. While on the students’ perspective, they believe deep and lasting learning of the lessons could be possible only if the right types of feedback were given to the patients as well. One of the participants shares his experience: “I have seen clinical supervisors asking about patients’ educational level. Even the professors sometimes check students’ training in this manner. The students also have to see if the patients can remember the lessons.”

The goal of evaluation

From the participants’ perspective, the goal of evaluation has to be presented to them clearly so that they may know what materials have to be emphasized over the course of education. Clarifying the purpose of education between the patients and students leads to their cooperation and removes any obstacles in the learning process. In addition, this is also advantageous for professors. A 24-year-old female midwifery student says: “I was frightened when I heard that I have to handle many baby deliveries well to pass this field of clinical practice, but once I was done with all the tasks, I found out that these practices were very advantageous and they helped me prepare for the future tasks.”

Educational effectiveness

The participants’ perspectives revealed that evaluation has to be carried out in a way to demonstrate the performance of the instructor and students over the course. Otherwise, educational effectiveness cannot be appraised and assessment would not be effective. The repeated question by one participants was: “How do we know if these instructions that we have received are of any use or if they can lead to change in health behavior?” The educational role of nurses and midwives in providing patients’ care in hospitals and health-care settings is undeniably relevant and effective education can significantly ease the burden of the health-care system. Unfortunately, this serious task has not been fully accomplished and there are deficiencies in providing health-care services. A 26-year-old female midwifery student shares her experience this way: “At present, patient education is the goal of the department and it is important for the officers in charge to ensure that the students to receive the necessary skills and training required in hospitals.”

Discussion

The findings of this study showed that interaction, teaching and learning opportunities, and reflective evaluation had parts in educating patients as the hidden curriculum both by the nursing and midwifery students.

Many researchers have analyzed the hidden curriculum and its dimensions. Portelli in his investigation showed that implicit aspects of the hidden curriculum refer to expectations. This can be concluded in both studies (ours and Portelli's research), interactive role in the formation of the hidden curriculum has been effective. Although in our paper, the interactions among doctors, hospital staff, and instructors among themselves and with patients in the training process were important, also in the study of Portelli, the learning outcomes in the hidden curriculum and school structure have been pointed out.[16] Communication style, ethical considerations, and attention to individual differences were presented in our study findings as interactions, but in the study of Anderson, it was observed that individual differences, ethics, and communication are part of the social features.[17] Ahola knows learning as a mechanism of social and scientific techniques in academia which originated from beliefs, values, norms, social classes and cultural issues, and in a word from the culture of the environment;[18] As a matter of fact, our and Ahola's research focused on the hidden curriculum in sustainable learning. The present report and Alikhany's similarly referred both to interactions and rules.[19] Mongwe discusses the role the following good examples but fails to discuss its negative aspects and confines his discussion solely to its positive aspects.[26] Hours of classes, disciplinary and academic atmosphere had a significant impact on the students’ perception of the hidden curriculum which is consistent with the findings of Taghipoor and Ghaffari[11] and Amini et al.[27] studies. Attention to the management of conflicts and the function of staff, doctors, and professors in the university and hospitals on socializing students in the present study was aligned with Lempp and Seale findings.[28]

Students in the present study have paid careful attention to the process of evaluation and its part as a hidden curriculum in transferring skills of teaching patients. The results of Mahram's study about the evaluation process were consistent with the present study. He considered the problems of the evaluation process as a cause of anti-educational experience in higher education,[29] but in the present paper, the students expressed reflective evaluation (in which the students took several feedbacks regarding their assessment results and aims of evaluation) as effective in transferring skills to teach patients. In truth, they stated reflective evaluation as part of a sustainable learning of the hidden curriculum.

From the students’ perspective, any evaluation, whether theoretical or practical, can lead to their hidden learning. A goal-driven education, they believed, can clarify the path of learning and education. According to them, at the end of the educational course, students should be able to find their weak and strong points and professors should be able to revise the curriculum, teaching, and assessment procedures based on the outcome of evaluations. None of the studies performed on this area have mentioned the part of reflective evaluation in patient education and it can be considered as a new area of study with various dimensions.

Conclusions

The findings of the present study indicate that interactions between health-care providers and patients had a crucial influence on students as part of the hidden curriculum in patient education. The positive aspect of the current study was its new approach in the investigation of the hidden curriculum in the nursing and midwifery professions considering their clinical nature which demands a dynamic instruction of nursing and midwifery students. The limitations of the present study include the inability to generalize the results with other universities and nursing and midwifery educational institutions due to the limited number of participants, its limitation in the scope of study regarding patient education and not exploring all the aspects of nursing and midwifery education.

Questionnaire development based on the findings and psychometrics is recommended. Furthermore, it is also recommended that the future studies should focus on investigation of the role of the hidden curriculum in creating the feeling of efficiency and responsibility in the nursing and midwifery students. Future studies may also explore the importance and role of the hidden curriculum in patient education in other medical professions such as public health specialists or medical practitioners.

Financial support and sponsorship

This article has been derived from MSc thesis in Nursing research project. This study was supported by a grant (#3/5/2015:1644) from the Deputy of Research at Bushehr Medical University, Bushehr, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank research vice-chancellor of the Bushehr University of Medical Sciences for his financial support (grant #3/5/2015:1644) and also the participants for their patience and assistance during this research study.

References

- 1.Barber-Parker ED. Integrating patient teaching into bedside patient care: A participant-observation study of hospital nurses. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48:107–13. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farahani MA, Sahragard R, Carroll JK, Mohammadi E. Communication barriers to patient education in cardiac inpatient care: A qualitative study of multiple perspectives. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17:322–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krapp KM. The Gale Encyclopedia of Nursing & Allied Health. Canada: Gale Group, Thomson Learning; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalantari S, Najafi K, Abbaszadeh A, Sanagoo A, Borhani F. Nurses’ perception of performance of patient education. Jentashapir J Health Res. 2012;2:167–74. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolaides-Bouman A, van Rossum E, Habets H, Kempen GI, Knipschild P. Home visiting programme for older people with health problems: Process evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:425–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deccache A, Aujoulat I. A European perspective: Common developments, differences and challenges in patient education. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heshmati Nabavi F, Memarian R, Vanaki Z. Clinical supervision system: A method for improving educational performance of nursing personnel. Iran J Med Educ. 2008;7:257–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghorbani R, Soleimani M, Zeinali MR, Davaji M. Iranian nurses and nursing students’ attitudes on barriers and facilitators to patient education: A survey study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14:551–6. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergenhenegouwen G. Hidden curriculum in the university. High Educ. 1987;16:535–43. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karimi Moonaghi H, Dabbaghi F, Oskouie F, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K. Learning style in theoretical courses: Nursing students’ perceptions and experiences. Iran J Med Educ. 2009;9:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taghipoor H, Ghaffari H. Survey of the hidden curriculum role in students disciplinary behavior from the teachers and managers perspective of Khalkhal female middle schools in 2009-2010 academic year. J Educ Sci. 2009;2(7):33–65. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehrmohammadi M. Curriculum Theories, Approaches and Perspectives. Mashhad: Astan Ghodse Razavi; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosallanezhad L, Morshed Behbahani B. The role of the teacher in creation of hidden dimentions of the curriculum. J Strides Dev Med Educ. 2013;10:130–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salehi SH, Rahimi M, Abedi HA, Bahrami M. Students experience with the hidden curriculum in faculty of nursing and midwifery of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Pejouhesh Med. 2003;27:217–23. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taheri N, Razavizadegan M. Importance of patient education from the viewpoint of nursing student in Abadan. Modern care Journal of Birjand university of medical sciences. 2011;8:100–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Portelli JP. Exposing the hidden curriculum. J Curriculum Stud. 1993;25:343–58. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson T. The hidden curriculum in distance education an updated view. Change Mag High Learn. 2001;33:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahola S. Hidden Curriculum in Higher Education: Something to Fear for or Comply to. Innovations in Higher Education, Helsinki, Finland. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alikhani MH, Mehrmohammadi M. Survey of unintended consequences (hidden curriculum) from the social environment of secondary schools in Isfahan. J Educ Psychol Sci. 2005;11:121–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mirzabeigi G, Sanjari M, Shirazi F, Heidari S, Salemi S. Nursing students’ and educators’ views about nursing education in Iran. Iran J Nurs Res. 2011;6:64–74. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biranvand S, Shini Jaberi P, Asadi Zaker M. Patient education in nursing viewpoint, the main executive obstacles. Aflak J. 2010;18:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holloway I, Wheeler S. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare. USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mongwe RN. Student Nurses’ Experiences of the Clinical Field in the Limpopo Province as Learning Field: A Phenomenological Study (Doctoral Dissertation) 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amini M, Mehdizade M, Mashallahinejad Z, Alizade M. A survey of relation between elements of hidden curriculum and scientific spirit of students. Q J Res Plann High Educ. 2012;17:81–103. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lempp H, Seale C. The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: Qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. BMJ. 2004;329:770–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7469.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahram B. The role of components of curriculum in students community identity (Case Study of Ferdowsi University) Stud Curriculum. 2006;1:3–29. [Google Scholar]