Abstract

Discourse analysis (DA) is an interdisciplinary field of inquiry and becoming an increasingly popular research strategy for researchers in various disciplines which has been little employed by health-care researchers. The methodology involves a focus on the sociocultural and political context in which text and talk occur. DA adds a linguistic approach to an understanding of the relationship between language and ideology, exploring the way in which theories of reality and relations of power are encoded in such aspects as the syntax, style, and rhetorical devices used in texts. DA is a useful and productive qualitative methodology but has been underutilized within health-care system research. Without a clear understanding of discourse theory and DA it is difficult to comprehend important research findings and impossible to use DA as a research strategy. To redress this deficiency, in this article, represents an introduction to concepts of discourse and DA, DA history, Philosophical background, DA types and analysis strategy. Finally, we discuss how affect to the ideological dimension of such phenomena discourse in health-care system, health beliefs and intra-disciplinary relationship in health-care system.

Keywords: Discourse analysis, health-care system, methodology

Introduction

For at least then years now, “discourse” and “discourse analysis (DA)” has been the fashionable term. Usually, in scientific research and debates, it is used indiscriminately, without being defined. Without a clear understanding of discourse theory and DA, it is difficult to comprehend important research findings and impossible to use DA as a research strategy. Hence, this paper aims to help health-care practitioner employ DA as an effective research strategy.

Materials and Methods

This study was a narrative review. Electronic databases such as PubMed, Medline, ProQuest, and science direct were searched using the keywords discourse analysis, methodology, and health-care system. A manual search of various journals and books was also carried out. Not only all the searched articles and books were included, but also highly relevant articles from English literature were considered for the present review.

Discourse analysis description

There are many explanations and definitions of discourse and DA.[1] Discourse has been defined as “a group of ideas or patterned way of thinking which can be identified in textual and verbal communications, and can also be located in wider social structures.”[2] In other definition “discourse is a belief, practice or knowledge that constructs reality and provides a shared way of understanding the world.” In a broad sense, discourses are defined as systems of meaning that are related to the interactional and wider sociocultural context and operate regardless of the speakers’ intentions. DA is a broad and diverse field, including a variety of approaches to the study of language, which derive from different scientific disciplines and utilize various analytical. DA examines language in use.[3] As suggested, by Fairclough, “discourse is the use of language as a form of social practice and DA is an analysis of how texts work within the sociocultural practice.”[4] DA focuses on the ways that language and symbols shape interpretations of negotiators’ identities, instrumental activity, and relationships.[5]

Discourse analysis history background

DA is both an old and a new discipline. Historically, DA path a way from linguistic approaches to socialistic approaches. Its origins can be traced back to the study of language, public speech, and literature more than 2000 years ago. One major historical source is undoubtedly classical rhetoric, the art of good speaking. Whereas the grammatica, the historical antecedent of linguistics, was concerned with the normative rules of correct language use, its sister discipline of rhetorical dealt with the precepts for the planning, organization, specific operations, and performance of public speech in political and legal settings.[6] The term of DA first came into general use following the publication of a series of papers by ZelligHarris beginning in 1952 and reporting on work from which he developed transformational grammar in the late 1930s.[7] DA in this decade concerned with such microelements of discourse as the use of grammar, rhetorical devices, syntax, sound forms and the overt meaning and content matter of words and sentences of a text or talk, and such macro structures as topics and themes. After two decades, a new form of DA emerged in the middle decades of the 60s and 70s, following the development of knowledge in the social sciences and humanities. Formal sentence grammars had been challenged from several sides and were at least complemented with new ideas about language use, linguistic variation, speech acts, conversation, other dialogs, text structures, communicative events, and their cognitive and social contexts. Much formal rigor and theoretical sophistication had to be temporarily bracketed out to formulate completely new approaches.[6]

A new cross-discipline of DA began to develop in most of the humanities and social sciences concurrently with and related to, other disciplines, such as anthropology, semiology, psycholinguistic, sociolinguistics, and pragmatics. Many of these approaches, especially those influenced by the social sciences, favor a more dynamic study of oral talk-in-interaction. In this view, DA concerned with how an individual's experience is socially and historically constructed by language and DA assumes that language constructs how we think about and experience ourselves and our relationships with others.[6] In Europe, Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida became the key theorists of the subject, especially of discourse. In this context, the term “discourse” no longer refers to formal linguistic aspects, but to institutionalized patterns of knowledge that become manifest in disciplinary structures and operate by the connection of knowledge, community and power. Since the 1970s, Foucault's works have had an increasing impact, especially on DA in the social sciences. Now DA as qualitative methods apply in various fields such as anthropology, ethnography, sociology, intellect, cognitive and social psychology, politic science, communication, and critical linguistics, and health-care system.

Philosophical background

Mainly DA philosophical base is a social constructionist approach.[8] Social constructionism is an umbrella term for a range of new theories about culture and society.[9] DA is just one among several social constructionist approaches, but it is one of the most widely used approaches within social constructionism.[10]

Discourse analytical approaches take as their starting point the claim of structuralist and poststructuralist linguistic philosophy, which our access to reality is always through language. With language, we create representations of reality that are never mere reflections of a preexisting reality but contribute to constructing reality. That does not mean that reality itself does not exist. Meanings and representations are real. Physical objects also exist, but they only gain meaning through discourse. Language, then, is not merely a channel through which information about underlying mental states and behavior or facts about the world are communicated. On the contrary, language is a “machine” that generates, and as a result constitutes the social world. This also extends to the constitution of social identities and social relations. It means that changes in discourse are a means by which the social world is changed.[9] In other words “individuals are not intentional agents of their own words, creatively and privately converting thoughts to sounds or inscriptions. Rather they gain their status as selves by taking a position within a preexisting form of language.”[11]

In terms of epistemology, many discourse theorists adopt a relativist view; they assume that there exist no objective grounds on which the truth of claims can be proven and propose that the value of knowledge should be evaluated according to other criteria, such as its applicability, usefulness and clarity.[12] Others, however, claim that relativism does not allow for a position from which social critique and action can be developed and adopt a critical realist position; they acknowledge that knowledge is always mediated by social processes but propose that underlying enduring structures do exist and that these can be known through their effects.[8]

Burr provided an outline of the general philosophical assumptions that underpin most discourse analytical approaches, drawing on the accounts of social constructionism.

They are as follows:

A critical approach to taken-for-granted knowledge - Our knowledge of the world should not be treated as objective truth. Reality is only accessible to us through categories, so our knowledge and representations of the world are not reflections of the reality “out there,” but rather are products of our ways of categorizing the world, or, in discursive analytical terms, products of discourse[10]

Historical and cultural specificity; We are fundamentally historical and cultural beings and our views of, and knowledge about, the world are the products of historically situated interchanges among people.[13] Consequently, the ways in which we understand and represent the world are historically and culturally specific and contingent: our worldviews and our identities could have been different, and they can change over time. This view match by this view that all knowledge is contingent is an anti-foundationalism and anti-essentialist[9]

The link between knowledge and social processes – Our ways of understanding the world are created and maintained by social processes.[10,13] Knowledge is created through social interaction in which we construct common truths and compete about what is true and false.[9]

The link between knowledge and social action - Within a particular worldview, some forms of action become natural, others unthinkable. Different social understandings of the world lead to different social actions, and therefore, the social construction of knowledge and truth has social consequences.[10,13]

Discourse analysis approaches

DA is not only one approach but also a series of interdisciplinary approaches that have been applied in varying ways, from purely linguistic research into a conversation on a “micro” level to the broadly historic philosophical, and societal context.[2] DA Different perspectives offer their own suggestions and to some extent, compete to appropriate the terms “discourse” and “DA” for their own definitions.[9] One major difference between the various types of DA is in their methods of analysis.[14]

DA is composed of two main dimensions, textual, and contextual. Textual dimensions are those which account for the structure of discourses, while contextual dimensions relate these structural descriptions to various properties of the social, political, or cultural context in which they take place.[6] The DA that is rooted in linguistics and in textual form is concerned with such microelements of discourse as the use of grammar, rhetorical devices, syntax, sound forms and the overt meaning and content matter of words and sentences of a text or talk, and such macro-structures as topics and themes. The contextual form examines the production and reception processes of discourse, with particular attention to the reproduction of ideology and hegemony in such processes, and the links between discourse structures and social interaction and situations.[2,6]

Some DA mixes one or more of these approaches; for example, one kind of critical DA (CDA) combines linguistic analysis and ideological critique.[4]

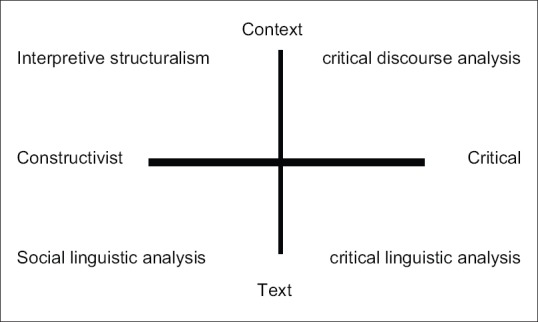

There are various categorizations of discourse analytical research.[15] Phillips describes four main styles of discourse analytical research [Figure 1]. The styles are categorized along two axes: (1) between text and context, and (2) between constructivist and critical approaches.[16]

Figure 1.

Four perspectives of discourse analysis

The first axis is about the degree to which research focuses on individual texts or on the surrounding texts.[15] Phillips distinguishes between a proximal and a distal context. The proximal context is the local context, for example, a discipline or science. The distal context is a broader social context, for example ecological, regional, or cultural settings.[16]

The second axis describes the degree to which the research focuses on ideology and power, as opposed to processes of social construction. The axes are seen as continua, not as dichotomies. Thus, combinations of elements of both axes are possible and usual.[16]

Jansen in his article summarized the four perspectives of DA that described by Phillips; they are as follows.

Social linguistic analysis

A social linguistic analysis is constructivist and focuses on individual texts. It gives insight into the organization and construction of these texts and how they work to construct and organize other phenomena. The focus is not on the exploration of the power dynamics in which the texts are implicated.

Interpretive structuralism

Similar to social linguistic analysis, these discourse analyses are interested in the way in which broader discursive contexts come into being. They are not directly concerned with power. Individual texts are more important as background material.

Critical linguistic analysis

Critical linguistic analysis shares with social linguistic analysis its focus on individual texts, but its main concern is with the dynamics of power that surround the text. The examination of individual texts is for understanding how the structures of domination of the proximal context are implicated in the text.

Critical discourse analysis

The main interest of CDA is in the discursive activity to construct and maintain unequal power relations. The distal context is of interest, that is, the ecological, cultural, or regional setting that surrounds individual texts.[15,16] The CDA process derived from the work of Fairclough and is a study of language as a social and cultural practice. It is based on the premise that texts have a constructive effect in shaping how we experience ourselves and others and how we act in relation to this, example, the ability to prescribe medication.[4]

In addition to the above DA types, there are other classifications for DA theoretical approaches.

Discursive psychology

Discursive psychology is part of the general movement of critical psychology, which has been reacting against mainstream social psychology, especially the sort of experimental psychology.[17] The aim of discursive psychologists is not so much to analyze the changes in society's “large-scale discourses,” which concrete language use can bring about, as to investigate how people use the available discourses flexibly in creating and negotiating representations of the world and identities in talk-in-interaction and to analyze the social consequences of this. Despite the choice of label for this approach “discursive psychology” its main focus is not internal psychological conditions. Discursive psychology is an approach to social psychology that has developed a type of DA to explore the ways in which people's selves, thoughts, and emotions are formed and transformed through social interaction and to cast light on the role of these processes in social and cultural reproduction and change.[9]

Historical discourse analysis

Historical DA is a poststructuralist approach to reading and writing history; a mode of conceptualizing history through a theorized lens of critique. Historical DA works against the objectivist fallacy of traditional positivist historical methods in decentering the authority of the historian as a neutral recorder of facts and the claim of historical writings as objective reconstructions of past events. In line with its intent to disrupt taken for granted ways of conceptualizing history, the task of historical DA is not to find truths about past events or to identify the origins or causes of past events, but to expose history as a genre contingent, ambiguous, and interpretive. Historical DA is, therefore, less a set methodology than a set of postmethodological methodologies.[18]

Foucaultian discourse analysis

Today the theoretical work of Michel Foucault is widely considered as being part of the theoretical body of social sciences such as sociology, social history, political sciences, and social psychology.[19] Discourse, as defined by Foucault, refers to: ways of constituting knowledge, together with the social practices, forms of subjectivity, and power relations which inhere in such knowledge's and relations between them. Discourses are more than ways of thinking and producing meaning. They constitute the “nature” of the body, unconscious and conscious mind and emotional life of the subjects they seek to govern.[20] Foucault's focus is on questions of how some discourses have shaped and created meaning systems that have gained the status and currency of “truth,” and dominate how we define and organize both ourselves and our social world while other alternative discourses are marginalized and subjugated, yet potentially “offer” sites where hegemonic practices can be contested, challenged, and “resisted”. In Foucault's view, social context in which certain knowledge's and practices emerged as permissible and desirable or changed. In his view knowledge is inextricably connected to power. Power has an important role in Foucault's view, and power is a process that operates in continuous struggles and confrontations that change, strengthen, or reverse the polarity of the force relations between power and resistance. This means that power is described as a relational process that is embodied in context-specific situations and is partially identifiable through its ideological effects on the lives of people. Power is productive of truth, rights, and the conceptualization of individuals, through the processes, or discursive practices of the human sciences and other major discourses such as social sciences, bureaucracy, medicine, law, and education.[21] Discourse analysts in this way need to be aware of the conceptualizations of power and resistance to be able to recognize them within a discourse. Emancipatory of the marginalized group is an important goal of recognizing power in Foucault's approach.

Analytical strategies

The concrete representation of discourses is texts or discursive “units.” They make have a variety of forms: formal written records, such as news information, company statements and reports, academic papers; spoken words, pictures, symbols, artifacts, transcripts of social interactions such as conversations, focus group discussions, and individual interviews; or involve media such as TV programs, advertisements, magazines, novels, etc. In fact, texts are depositories of discourses, they “store” complex social meanings produced in a particular historical situation that involved individual producer of a text unit, and social surrounds that is appealed to the play.[1] If we are to understand discourse, we should also understand the context, in which they arise.[6] Researchers usually distinguish two types of context: broad and local. There is also a more detailed classification of the degree of a context, involved in a study: micro-discourse (specific study of language), meso-discourse (still study of a language but with a broader perspective), grand discourse (study of a system of discourses that are integrated in a particular theme such as culture), and mega discourse (referring to a certain phenomenon like globalization).[22]

DA is a process rather than a step-by-step research method and can be employed within different epistemological paradigms.[23] Crowe described the most important questions in data analysis; how it is structured as particular type of text; what politeness strategies are used; how subject positions are constructed; the types and functions of the language used and the identification of keywords; the thematic structure; how social relations are constructed; and how reality is represented.

The content of discourses can be investigated using many different tools. In a specific analysis, it may be a problem where to begin and which tools to select. In this section, we will present four strategies expressed by Jørgensen and Phillips which can be used across all the approaches to provide an overall understanding of the material and identify analytical focus points for further investigation.

Comparison

The simplest way of building an impression of the nature of a text is to compare it with other texts. The strategy of comparison is based theoretically on the structuralist point that a statement always gains its meaning through being different from something else which has been said or could have been said. In applying this strategy, the researcher asks the following questions: In what ways is the text under study different from other texts and what are the consequences? Which understanding of the world is taken for granted and which understandings are not recognized?

Substitution

Substitution is a form of comparison in which the analyst herself creates the text for comparison. Substitution involves substituting a word with a different word, resulting in two versions of the text which can be compared with one another; in this way, the meaning of the original word can be pinned down. Through such comparisons, a picture can gradually be formed of how the text establishes her identity in relation to the world around her including the decisions she constructs as within her control and the ones that she constructs as out with her control. In common with the strategy of comparison, substitution draws on the structuralist point that words acquire their meaning by being different from other words. In the case of a long text, a single word can be substituted throughout the text to see how it changes the meaning of the text as a whole. However, textual aspects other than single words can also be subject to substitution.

Exaggeration of detail

The exaggeration of detail involves blowing up a particular textual detail out of proportion. The analyst may have identified a textual feature which appears odd or significant, but, as it is just one isolated feature, does not know what its significance is or how it relates to the text as a whole. To explore the significance of the feature, one can overexaggerate it, and then ask what conditions would be necessary in order for the feature to make sense and into what overall interpretation of the text the feature would fit.

Multivocality

The strategy of multivocality consists of the delineation of different voices or discursive logics in the text. The strategy is based on the discourse analytical premise concerning intertextuality– that is, the premise that all utterances inevitably draw on, incorporate or challenge earlier utterances. The aim of the strategy is to use the multivocality to generate new questions to pose to the text: what characterizes the different voices of the text? When does each voice speak? What meanings do the different voices contribute to producing?

Validation and rigor

DA is a highly interpretative process that acknowledges that multiple interpretations can emerge from the data.[4] DA is an interpretative process that can result in different researchers examining the same data yet arriving at different findings. The reliability and validity of findings, therefore, rely on the strength and logic of the researcher's argument in reports and presentations pertaining to study findings.[6] Crowe offers several key questions to consider when establishing rigor in DA studies:

Methodological rigor

Does the research question “fit” the DA

Do the texts under analysis “fit” the research question

Have sufficient resources, including historical, political, and clinical resources, been sampled

Has the interpretative paradigm been described clearly

Are the data-gathering and analysis congruent with the interpretative paradigm

Is there a detailed description of the data gathering and analytic processes

Is the description of the methods detailed enough to enable readers to follow and understand context?

Interpretative rigor

Have the linkages between the discourse and findings been adequately described

Is there inclusion of verbatim text to support the findings

Are the linkages between the discourse and the interpretation plausible

Have these linkages been described and supported adequately

How are these findings related to existing knowledge in the subject?

DA application in health-care system

The nature of the knowledge fundamental to health care and the power it wields during its practice, is of continuing interest to philosophers, social scientists and anthropologists, as well as to those individuals who directly use it in administering health care, namely, doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals. The development of sociopolitical critique has centered on the nature of the foundations of knowledge and how this influences our present understanding of the human condition. With the advent of the modern world, there have been continuing controversies about the essential characteristics of rationality.[21]

In Foucault's view, social context in which certain knowledge's and practices emerged as permissible and desirable or changed. In his view knowledge is inextricably connected to power. Power has an important role in Foucault's view, and power is a process that operates in continuous struggles and confrontations that change, strengthen, or reverse the polarity of the force relations between power and resistance. This means that power is described as a relational process that is embodied in context-specific situations and is partially identifiable through its ideological effects on the lives of people. Power is productive of truth, rights, and the conceptualization of individuals, through the processes, or discursive practices of the human sciences and other major discourses such as social sciences, bureaucracy, medicine, law, and education.[22,24]

DA has the potential to reveal valuable insights into the social and political contexts in which varied discourses about health take place. Areas of research which are relevant to healthcare concerns include the discourses of: the interpersonal communication processes between doctors or nurse and patients, interprofessional conversation, in-depth interviews about lay health beliefs, conversations between lay people about health risks and issues, government-sponsored health promotion messages, health information in the mass entertainment and news media, service protocols, information/education pamphlets for patients; texts describing particular understandings of health and illness or clinical approaches to treatment medical and health-care journals and official texts, textbooks in health-care specialties, health care's system communication about such disease, paternalistic manners in health-care system.

Human is one of the most important concepts in health-care system. Crowe believes that “Individuals can be considered as particular individuals, The meaning and value preexists the identification of these characteristics in an individual, and thus language does not reflect an external reality but expresses cultural conventions.”[20] Hence, we can say emancipatory of the oppressed group, marginalized patient (cause of race, ethnicity or disease types, such as HIV patient) and giving the voice is the one of the most important uses of DA in health care system.

In this part of article to learn more about the DA application in health care system, we expressed summary an article in this area.

Conclusion

DA as a qualitative approach has an important role in health-care system because health-care system needs to be knowledgeable across the multiple paradigms and perspectives that inform an understanding of the biological, psychological, social, cultural, ethical, and political dimensions of human lives.”[25] Practice in this area is a political, cultural, and social practice and needs to be understood as such to improve the quality of care provided. Effective clinical reasoning relies on employing several different kinds of knowledge and research[26] that draw on different perspectives, methodologies, and techniques to generate the breadth of knowledge and depth of understanding of clinical practices and patients’ experiences of those practices. DA can make a contribution to the development of this knowledge.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bondarouk T, Ruel H. Discourse Analysis: Making Complex Methodology Simple. Turku School of Economics and Business Administration Publisher. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lupton D. Discourse analysis: A new methodology for understanding the ideologies of health and illness. Aust J Public Health. 1992;16:145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1992.tb00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wetherell M, Taylor S, Yates SJ. Discourse as Data: A Guide for Analysis. London, U.K: Sage Publications Ltd; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fairclough N, Mulderrig J, Wodak R. Critical discourse analysis. Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, SAGE Publications Ltd; edition. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Putnam LL. Negotiation and discourse analysis. Negotiation J. 2010;26:145–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Dijk TA. News as Discourse. London: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nevin BE. The Legacy of Zellig Harris: Language and Information into the 21st Century. Vol 1: Philosophy of Science, Syntax and Semantics. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker I. Critical Discursive Psychology. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jørgensen MW, Phillips LJ. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burr V. Social Constructionism. 2 edition. London: Routledge; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gergen KJ. The Saturated Self. Vol. 278. New York: Basic Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potter J. Discourse analysis and discursive psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gergen KJ. The social constructionist movement in modern psychology. Am Psychol. 1985;40:266. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potter J, Wiggins S. Discursive psychology. Handbook of qualitative research in psychology. London: Sage; 2007. [Last accessed 2017 Nov 07]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jansen I. Discourse analysis and foucault's “archaeology of knowledge”. Int J Caring Sci. 2008;1:107–11. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips N. Discourse analysis: Investigating Processes of Social Construction. Vol. 50. London: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Billig M. Discursive psychology, rhetoric and the issue of agency. [Texte anglais original] Semen Revue de Sémio-Linguistique des Textes et Discours journal. 2009;(27) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park Y. Historical Discourse Analysis. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz-Bone R, Bührmann AD, Rodríguez EG, Schneider W, Kendall G, Tirado F. The Field of Foucaultian Discourse Analysis: Structures, Developments and Perspectives. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung. 2008:7–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weedon C. 16 n Feminism & The Principles of Poststructuralism. Cultural Theory and Popular Culture; Reader. University of Georgia; 1998. p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powers P. The philosophical foundations of Foucaultian discourse analysis. Crit Approaches Discourse Anal Across Discip. 2007;1:18–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvesson M, Karreman D. Varieties of discourse: On the study of organizations through discourse analysis. Hum Relat. 2000;53:1125–49. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crowe M. Discourse analysis: Towards an understanding of its place in nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2005;51:55–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henderson A. Power and knowledge in nursing practice: The contribution of foucault. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20:935–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20050935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yazdannik A, Yekta ZP, Soltani A. Nursing professional identity: An infant or one with alzheimer. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17:S178–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammadi S, Nik Y, Reza A, Yousefy A. A glimpse in the challenges in Iranian academic nursing education. Iran J Med Educ. 2014;14:323–31. [Google Scholar]