Abstract

Objective

To identify eating styles from 6 eating behaviors and test their association with Body Mass Index (BMI) among adults.

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of self-report survey data

Setting

12 primary care and specialty clinics in 5 states

Participants

11,776 adult patients consented to participate; 9,977 completed survey questions.

Variables measured

Frequency of eating healthy food; frequency of eating unhealthy food; breakfast frequency; frequency of snacking; overall diet quality; and problem eating behaviors. The primary dependent variable was BMI, calculated from self-reported height and weight data.

Analysis

Kmeans cluster analysis of eating behaviors was used to determine eating styles. A categorical variable representing each eating style cluster was entered in a multivariate linear regression predicting BMI, controlling for covariates.

Results

Four eating styles were identified and defined by healthy vs. unhealthy diet patterns and engagement in problem eating behaviors. Each group had significantly higher average BMI than the healthy eating style: healthy with problem eating behaviors (β=1.9, p<0.001); unhealthy (β=2.5, p<0.001), and unhealthy with problem eating behaviors (β=5.1, p<0.001).

Conclusions

Future attempts to improve eating styles should address not only the consumption of healthy foods, but also snacking behaviors and the emotional component of eating.

Keywords: Obesity, Body Mass Index, Nutrition, Behavioral Science, Eating Patterns

INTRODUCTION

Fighting obesity requires more than “eat less and exercise more.” Certainly caloric intake and physical activity frequency/intensity are the primary determinants of energy balance. However, both weight loss and maintenance of healthy weight are best achieved through sustained adherence to a broader range of healthy eating (e.g., increased fruit/vegetable intake) and physical activity (e.g., reduced sedentary time) behaviors. Based on the foundational understanding of the complex and multi-level determinants of healthy eating and healthy physical activity, much work has been done to develop interventions that facilitate these healthy behaviors.1, 2 And the stakes couldn’t be higher: in the United States obesity now affects 36.5% of adults and 17.0% of children.3 With the long-term health complications of obesity, including diabetes, heart disease, and cancer, the continued effort to understand which eating behaviors support achieving a healthy weight is of paramount importance.4, 5

Changes in eating behaviors have been independently associated with long term changes in weight.6 In particular, behaviors such as skipping meals, snacking, drinking sweetened beverages, and eating “fast food” have been frequently studied as potential contributors to obesity.7–9 Strong evidence links skipping breakfast with obesity, particularly among children.10, 11 However, a recent meta-analysis of 153 articles examining the association between eating behaviors and obesity among adults and children concluded that the evidence was insufficient to draw meaningful conclusions due to two major limitations.12 First, most existing studies have not adequately considered potential confounders of the proposed associations. Second, most existing studies have only considered how a single eating behavior is associated with obesity, not accounting for the contribution of other potentially-related eating behaviors.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to address the existing gap in the literature by considering how a broad range of eating behaviors relate to Body Mass Index (BMI), controlling for potential confounders including socio-demographics (i.e., age, gender, race/ethnicity) and physical activity in a large sample of adults. This was accomplished by first considering how six measures of diet quality and eating behaviors clustered together into patterns of eating styles, and then testing whether those eating styles were associated with BMI.

METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Analyses were conducted on cross-sectional survey data collected between August 2014 and November 2015. The primary mode of survey administration was via an electronic survey delivered on a tablet computer or an emailed survey link using REDCap.13 Participants recruited in person also had the option to complete a paper survey. The survey consisted of 72 items that queried participants about demographic and background information as well as health behaviors, and took participants an average of 17 minutes to complete. This study received approval from the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board. All participants signed informed consent prior to participating and received a $10 gift card for completing the survey.

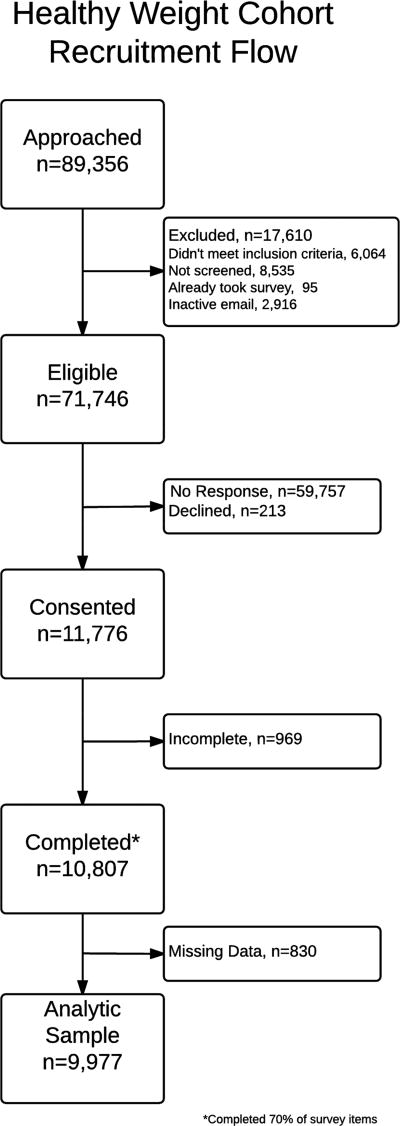

Patients were recruited from medical clinics in three health networks from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)-funded Mid-South Clinical Data Research Network (CDRN).14 The Mid-South CDRN integrates a clinical data infrastructure across the United States, consisting of: (1) Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) partnering with Meharry Medical College, (2) the Vanderbilt Healthcare Affiliated Network (VHAN), (3) Greenway Health, and (4) the Carolinas Collaborative, a consortium of 4 academic health systems and multiple community health systems across North Carolina and South Carolina. This study recruited participants from Vanderbilt, VHAN, and Greenway. The final sample of participants was recruited from 12 medical clinics, which were a mixture of primary care and subspecialty clinics. Recruitment occurred using four principal approaches: face-to-face recruitment in medical clinics, an email sent directly from a patient’s medical provider, an email sent from the research team, or an email sent from a clinic’s medical director. To be eligible, participants: 1) were ≥18 years old; 2) had ≥1 clinic note in the electronic health record (EHR) since April 30, 2009; 3) had ≥2 weight measures in the EHR since April 30, 2009; and 4) had ≥1 height measurement in the EHR after age 18. The survey was conducted exclusively in English. Participants were excluded if they had a mental condition or visual acuity that precluded their participation (assessed by research team at time of face-to-face survey administration). See Figure 1 for a diagram of recruitment flow for this study.

Figure 1.

Of the 11,776 participants who consented to participate, 10,807 (91.8%) completed at least 70% of survey items, and 9,977 respondents had complete data for analysis. The response rate as defined by the Council of American Survey Research Organizations (CASRO) is 16.4%.23

Measures

The primary independent (predictor) variables consisted of six self-report eating behaviors: 1) frequency of eating healthy food (2 items); 2) frequency of eating unhealthy food (3 items); 3) breakfast frequency (1 item); 4) frequency of snacking (1 item); 5) overall diet quality (1 item); and 6) problem eating behaviors (4 items). A complete list of survey items included in this analysis and how they were scored is available in Appendix A. The frequency of healthy and unhealthy food scores as well as the measure of problem eating behaviors were developed based on factor analysis of 9 items from the survey, each of which were answered on a 4-point response scale from 1 = “never” to 4 = “often; once a day or more.” The “healthy food” variable was a composite frequency of eating fruits and vegetables (range 2–8). The “unhealthy food” variable was a composite frequency of consuming fast food, sugary drinks, and desserts (range 3–12). Self-reported frequency of eating breakfast and snacking were scored on a 3-point response scale from 0 = “never” to 2 = “daily”. Self-reported diet quality was scored on a 5-point response scale from 1 = “poor” to 5 = “excellent”. These items have been used in previous survey research, and have demonstrated validity in those contexts (i.e., a prospective cohort of 3000 hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndrome or heart failure;15 and 67,928 participants enrolled in the Southern Community Cohort Study).16 The 4-item measure of problem eating behaviors was based on a previously validated scale, and in this study had a high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.83).17

The primary dependent variable was body mass index (BMI), calculated from self-reported height and weight data. Demographic variables were all self-reported and included age, gender, race/ethnicity, and household income. Self-reported physical activity was assessed as a potential confounder with a single item that ranged from 1 = “I am very inactive” to 5 = “I am active most days.”

Demographic characteristics including age, gender, household income, and race/ethnicity were summarized using mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Annual household income was categorized in 3 mutually exclusive categories (<$35,000, $35,000–$75,000, >$75,000). Race/ethnicity was categorized into 4 mutually exclusive categories (White, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; and Other, non-Hispanic).

Analytic Strategy

Kmeans cluster analysis was used for the six independent eating behavior variables to determine eating styles. A scree plot of the weighted sum of squares and the proportional reduction of the weighted sum of squares against a range of potential clusters (range 1–20) was used to identify the optimal number of clusters necessary to pre-specify in the kmeans algorithm.18 Based on the scree plot, 4 initial centroids were randomly identified, and 10,000 repetitions of the kmeans algorithm were conducted to achieve convergence of the solution (i.e., no observations changed clusters for the final centroids).19 A kmeans cluster analysis was first conducted on roughly half of the sample (recruited from one of the three health systems in the CDRN). The analysis was then repeated on the other half of the sample. These two independent cluster analyses generated similar cluster centers with nearly identical relationships with BMI. Consequently, the kmeans cluster analysis was repeated on the total sample (n=9,977), which is what is reported in this paper. Because kmeans cluster analysis is sensitive to missing data, only individuals with complete data on BMI and the six predictor variables were included.

In order to represent the patterns of eating behaviors in each cluster, each of the six predictor variables was standardized and presented as the mean z-score of each variable as it is grouped per cluster (this is also done within the kmeans clustering algorithm). This allows for comparison across scales with different numbers of items and score ranges.

A categorical variable with levels representing each replicable cluster served as the primary independent variable for the subsequent set of analyses. The primary analysis used multiple linear regression with BMI as the dependent variable, adjusting for age (continuous), gender (dichotomous), household income (ordinal), race/ethnicity (categorical), and physical activity (continuous). A secondary analysis in which 3 separate logistic regressions compared categorical weight status as the dependent variable and eating cluster as the independent variable (controlling for the same covariates) was completed to help clarify the clinical interpretation of the results. Weight status was defined using the following cut points: normal weight (ref) = BMI ≥18.5 & < 25kg/m2; overweight = BMI ≥25 & <30 kg/m2; obesity=BMI ≥30 & <40 kg/m2; morbid obesity=BMI ≥40 kg/m2.3 Statistical significance was set at α<0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 11,776 respondents who consented to participate in the survey, 9,977 (84.7%) had complete data on study variables and were included in this analysis. Full demographic characteristics of the overall sample are listed in Table 1. The majority of respondents were female, self-identified as Non-Hispanic White, and 41.0% had an annual household income greater than $75,000. Although the average BMI was 29.3 (SD 7.4), over a third of the respondents had obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) with almost 20% having morbid obesity (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of survey participants overall and by eating style

| Eating Style | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics |

Overall n=9,977 |

Healthy n=3,687 |

Healthy with problem eating behaviors n=2,219 |

Unhealthy n=2,164 |

Unhealthy with problem eating behaviors n=1,907 |

||||||

| Mean/% | SD/n | Mean/ % |

SD/n | Mean/ % |

SD/n | Mean/ % |

SD/n | Mean/ % |

SD/n | ||

| Age (years) | 50.6 | 15.9 | 54.8 | 16.1 | 48.4 | 16.0 | 50.1 | 15.4 | 46.6 | 14.2 | |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 29.3 | 7.4 | 27.3 | 6.5 | 28.7 | 7.0 | 30.2 | 7.4 | 32.9 | 8.0 | |

| Gender, female | 71.8% | 7,141 | 63.4% | 2,329 | 78.6% | 1,740 | 70.1% | 1,513 | 82.3% | 1,559 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 84.2% | 8,256 | 81.5% | 2,948 | 87.1% | 1,898 | 84.8% | 1,803 | 85.3% | 1,607 | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 10.2% | 1,003 | 12.0% | 435 | 6.2% | 135 | 11.7% | 249 | 9.8% | 184 | |

| Hispanic | 1.9% | 184 | 2.3% | 84 | 1.9% | 42 | 1.3% | 28 | 1.6% | 30 | |

| Other, Non-Hispanic | 3.7% | 365 | 4.2% | 152 | 4.8%) | 104 | 2.2% | 47 | 3.3% | 62 | |

| Household Income | |||||||||||

| <$35,000 | 23.2% | 2,289 | 24.5% | 804 | 16.9% | 345 | 23.1% | 457 | 24.9% | 440 | |

| $35,000–$75,000 | 35.9% | 3,545 | 33.2% | 1,089 | 34.1% | 695 | 41.4% | 820 | 37.5% | 665 | |

| >$75,000 | 41.0% | 4,055 | 42.4% | 1,392 | 49.0% | 999 | 35.6% | 706 | 37.6% | 665 | |

Eating Style Determination

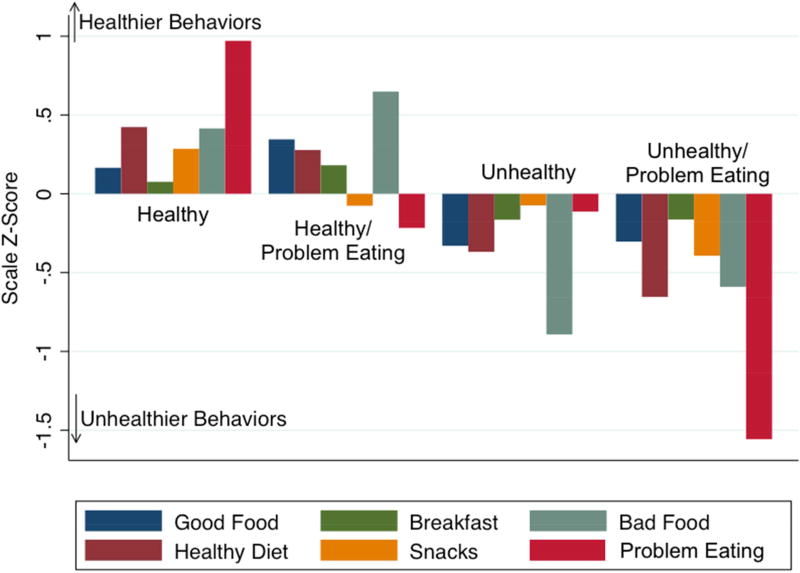

The kmeans cluster analysis revealed four coherent patterns of eating behaviors (Figure 2). Items related to healthy diet clustered together, so a healthy diet pattern was defined by higher scores on the healthy food scale, lower scores on the unhealthy food scale, higher scores on the generally healthy diet quality item, and higher frequency of eating breakfast. More frequent snacking behaviors clustered with an unhealthy diet pattern. The greatest discrimination between the clusters was based on the combination of healthy/unhealthy diet pattern and problem eating behavior scores, leading to four patterns of eating styles: healthy; healthy with problem eating behaviors; unhealthy; and unhealthy with problem eating behaviors.

Figure 2.

Four clusters of eating styles were identified using kmeans cluster analysis. Standardized z-scores for each of the scales included in the kmeans analysis are shown within the final cluster assignment. Scales are oriented so that healthier behaviors have a positive z-score, and unhealthier behaviors have a negative z-score.

Healthier clusters of eating styles were associated with more frequent vegetable intake, with nearly 75% of participants in the two healthy clusters reporting daily vegetable intake compared to just over 50% of those in the two unhealthy clusters (P <0.001). Healthier clusters of eating styles were also associated with more frequent fruit intake, with about 60% of participants in the healthy clusters reporting daily fruit intake compared to about 40% in the unhealthy clusters (P <0.001). In addition, healthier clusters of eating styles were associated with more frequent physical activity, with 40% of the participants in the healthy cluster reporting daily physical activity compared to 28.5% in the healthy with problem eating behaviors cluster, 23.8% in the unhealthy cluster, and only 14.3% in the unhealthy with problem eating behaviors cluster (P <0.001).

Correlates of Eating Styles

There were significant differences in the demographic characteristics of the individuals based on the cluster of feeding style to which they were assigned (Table 1). Respondents in the unhealthy with problem eating behaviors cluster had the youngest mean age, and had a higher percentage of women.

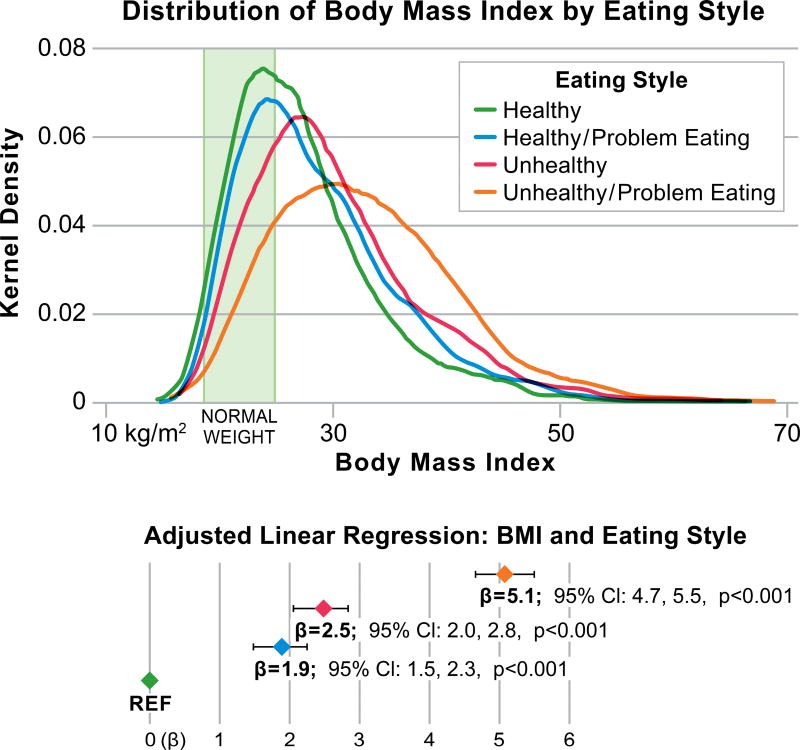

The average (SD) BMI for individuals in the healthy eating cluster was 27.3 (6.5) kg/m2, compared to 28.7 (7.0) kg/m2 in the healthy with problem eating, 30.2 (7.4) kg/m2 in the unhealthy cluster, and 32.9 (8.0) kg/m2 in the unhealthy with problem eating. Using the healthy cluster as the referent group in an adjusted linear regression model, each of the other clusters was significantly associated with higher average BMI (Figure 3): unhealthy with problem eating (β=5.0, 95% CI [4.66, 5.50], P <0.001); unhealthy (β=2.5, 95% CI [2.07, 2.85], P <0.001), and healthy with problem eating (β=1.9, 95%CI [1.50, 2.27], P <0.001). In the secondary analysis using multivariable adjusted logistic regression, the odds of having overweight, obesity, and morbid obesity were all higher based on cluster of eating style. The odds ratios (OR) for being overweight by eating style were: healthy (ref), healthy with problem eating (OR 1.6, 95% CI [1.4, 1.8], P <0.001), unhealthy (OR 2.0, 95% CI [1.70, 2.34], P <0.001), unhealthy with problem eating (OR 2.8, 95% CI [2.3, 3.4], P <0.001). The OR for having obesity by eating styles were: healthy (ref), healthy with problem eating (OR 2.1, 95% CI [1.76, 2.55], P <0.001), unhealthy (OR 2.5, 95% CI [2.09, 3.07], P <0.001), unhealthy with problem eating (OR 5.8, 95% CI [4.70, 7.2], P <0.001). The OR for having morbid obesity by eating styles were: healthy (ref), healthy with problem eating (OR 2.4, 95% CI (1.93, 2.89, P <0.001), unhealthy (3.0, 95% CI [2.44, 3.65], P <0.001), unhealthy with problem eating (OR 8.9, 95% CI [7.17, 11.06], P <0.001).

Figure 3.

Distribution of Body Mass Index (BMI) as measured by kernel density according to cluster of eating behavior. The default STATA settings for kernel density were used, including the Epanechnikov kernel and the calculated “optimal” bandwidth of the kernel. The inset figure shows the adjusted β and 95% confidence interval (CI) from the linear regression evaluating the association between eating cluster and BMI, controlling for age, gender, household income, race/ethnicity, and physical activity. The referent group is the healthy eating cluster.

DISCUSSION

These data demonstrate four coherent patterns of behaviors reflecting eating styles that are associated with BMI, independent of other demographic covariates. The most notable characteristic of these clusters is the discriminant value of combining the frequency of eating healthy and unhealthy foods with problem eating behaviors (i.e. overeating, impulsive eating, and emotional eating). Specifically, respondents who reported a healthy diet pattern had higher average BMI as well as a higher frequency of obesity and morbid obesity when they also reported engaging in more frequent problem eating behaviors. Respondents who reported an unhealthy diet pattern even in the absence of problem eating behaviors had a higher BMI than those with a healthy diet who also avoided problem eating behaviors. Respondent BMI and the proportion of individuals with obesity or morbid obesity was highest if respondents had an unhealthy diet pattern and simultaneously engaged in problem eating behaviors. Thus these results demonstrate that both unhealthy eating patterns and problem eating behaviors independently increase the odds of a person having obesity or morbid obesity. When unhealthy eating patterns and problem eating behaviors were combined, the odds ratio of obesity was 5.8 and the odds ratio of morbid obesity was 8.9. These findings suggest that clusters of eating behaviors may be more clinically relevant than any single component dietary assessment.

These data have direct implications for developing interventions and clinical recommendations for eating behaviors to support healthy weight. One of the main advantages of the clustering approach used for this analysis is that it can move past the examination of a single behavior. For example, skipping breakfast and eating at fast food restaurants have each been associated with higher BMI, both cross-sectionally and in longitudinal data.12 These data are consistent with those findings, in that unhealthy diet patterns including consumption of fast food (e.g., pizza), sugary drinks, and desserts (including candy) were associated with higher BMI. These data also suggest that snacking behaviors cluster with unhealthy eating patterns, which is important for addressing the potential effect of snacking on an unhealthy weight trajectory. Additionally, these data highlight the importance of problem eating behaviors such as overeating, impulsive eating, and emotional eating. Regardless of diet quality or the frequency of healthy food consumption, problem eating behaviors confer an additional risk of higher BMI. Because the problem eating behaviors questionnaire used in this study (PDQ-4) has only 4 items, it may be possible to incorporate screening for these types of behaviors into routine clinical practice.

One of the main limitations of this study is that it is cross-sectional, limiting causal inference. This is particularly important in this context as it is unclear whether unhealthy eating patterns precede obesity or vice versa.20 In addition, all of the data are self-reported and could therefore be affected by a social desirability bias, the direction of which is uncertain as the outcome (BMI) is likely related to the bias. However, chart review on approximately half of those surveyed showed a high correlation (ρ=0.94) between self-reported and objectively measured weight, somewhat alleviating the concern about social desirability bias. While the items dealing with diet and exercise have been used successfully in other studies, it is a limitation that we did not re-validate them with this specific population before including them in this survey, although the pattern of associations of those items with BMI in this study provides strong evidence of their construct validity. To minimize participant burden, the measure of physical activity was limited to a single item, which may not have been sufficiently sensitive to detect variation in the behavior. Selection bias may also be a concern, given the large percentage of individuals recruited online (or electronically). Consequently, the sample studied was from a predominantly older, female population and may not be generalizable to a broader, more racially or ethnically diverse population. This would suggest that this type of analysis be confirmed in additional demographic groups before broad policy or program implications are implemented. However, the geographic variation of the sample mitigates this concern to a degree, and the percentage of patients with obesity in this sample (38%) closely mirrors the recently reported national prevalence.3 While the items included in this survey have been validated in other populations, and while the strong associations with BMI in this study provide preliminary evidence of construct validity, they have not been validated in this specific population, which may have led to a misclassification bias.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

This large sample, cross-sectional analysis describes unique coherent eating styles, recognizing the importance of both snacking and problem eating behaviors within the context of healthy or unhealthy food choices. These distinct eating styles were strongly associated with BMI. This study provides the groundwork for future longitudinal studies to investigate these potential causal relationships in the service of obesity prevention. Furthermore, these data are consistent with recommendations from multiple professional organizations21, 22 and indicate that future attempts to improve healthy eating behaviors through individual dietary counseling and public health initiatives should address not only the consumption of healthy foods, but also snacking behaviors and the affective (i.e., emotional) component of eating.

Acknowledgments

The Mid-South CDRN was initiated and funded by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) through the contract CDRN-1306-04869, the Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research with grant support from (ULTR000445 from NCATS/NIH), and institutional funding. Dr. Heerman’s time was supported by a K12 grant from the AHRQ (K12HS022990) and a K23 grant from the NHLBI (K23 HL127104).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Huang TT, Drewnosksi A, Kumanyika S, Glass TA. A systems-oriented multilevel framework for addressing obesity in the 21st century. Preventing chronic disease. 2009;6:A82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD001871. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. NCHS Data Brief, no 219. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Prevalence of Obesity among adults and young: United States, 2011–2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhupathiraju SN, Hu FB. Epidemiology of Obesity and Diabetes and Their Cardiovascular Complications. Circ Res. 2016;118:1723–1735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2392–2404. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:36–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenheck R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2008;9:535–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes TL, French SA, Mitchell NR, Wolfson J. Fast-food consumption, diet quality and body weight: cross-sectional and prospective associations in a community sample of working adults. Public health nutrition. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015001871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkey CS, Rockett HR, Gillman MW, Field AE, Colditz GA. Longitudinal study of skipping breakfast and weight change in adolescents. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2003;27:1258–1266. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Heijden AA, Hu FB, Rimm EB, van Dam RM. A prospective study of breakfast consumption and weight gain among U.S. men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2463–2469. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mesas AE, Munoz-Pareja M, Lopez-Garcia E, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Selected eating behaviours and excess body weight: a systematic review. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2012;13:106–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenbloom ST, Harris P, Pulley J, et al. The Mid-South clinical Data Research Network. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:627–632. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyers AG, Salanitro A, Wallston KA, et al. Determinants of health after hospital discharge: rationale and design of the Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) BMC Health Services Research. 2014;14:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Signorello LB, Munro HM, Buchowski MS, et al. Estimating nutrient intake from a food frequency questionnaire: incorporating the elements of race and geographic region. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;170:104–111. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stetson B, Schlundt D, Rothschild C, Floyd JE, Rogers W, Mokshagundam SP. Development and validation of The Personal Diabetes Questionnaire (PDQ): a measure of diabetes self-care behaviors, perceptions and barriers. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2011;91:321–332. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makles A. Stata tip 110: How to get the optimal k-means cluster solution. Stata J. 2012;12:347–351. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan P-N, Steinbach M, Kumar V. Introduction to data mining. 1. Boston: Pearson Addison Wesley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludwig DS, Friedman MI. Increasing adiposity: consequence or cause of overeating? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311:2167–2168. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raynor HA, Champagne CM. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Interventions for the Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2016;116:129–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes A. 7. Obesity Management for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes care. 2017;40:S57–S63. doi: 10.2337/dc17-S010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Organizations CoASR. On the Definition of Response Rates. 1982 [Google Scholar]