Abstract

Background:

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is important cause of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer. Moxifloxacin is effective antibiotic for treatment for H. pylori. However, there were limited studies as first line therapy. Probiotics had been shown to decrease therapy-related side-effect and increase eradication rate. Aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of moxifloxacin-dexlansoprazole based triple therapy with probiotic for H. pylori treatment in Thailand.

Methods:

Patients with H. pylori infected gastritis were randomized to receive 7- or 14-day moxifloxacin-dexlansoprazole based triple therapy with probiotic or placebo. Regimen consisted of 60 mg dexlansoprazole twice daily, 400mg moxifloxacin once daily, 1g clarithromycin MR once daily. Probiotic used in this study was 282.5mg Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii) in capsule prescribed twice daily. CYP2C19 genotyping, antibiotic susceptibility tests, and CagA genotyping were also done. Successful eradication was defined as a negative 13C-urea breath test at least 4 weeks after treatment.

Results:

Total of 108 subjects was enrolled (27 each to 7- and 14-day regimens with probiotic or placebo). Antibiotic susceptibility tests showed 29% fluoroquinolone, 19% metronidazole and 4% clarithromycin resistance. CYP2C19 genotyping demonstrated 43%, 47% and 11% were rapid, intermediate and poor metabolizers, respectively. CagA genes were positive in all patients. Eradication rates of 7-day and 14-day regimens with probiotic were 100%, and 93% respectively. There were no significant differences between eradication rate of 7-day and 14-day regimen with or without probiotics. Regarding side-effects, incidence of nausea, abdominal discomfort, bitter taste, and diarrhea were significantly lower in regimen with probiotic group compared with placebo(7.4%vs. 22.2%; p=0.028, 0.00%vs.14.8%; p=0.003, 35.2%vs.70.4%; p=0.0002, and 0.00%vs.9.3%; p=0.028, respectively).

Conclusions:

7-day moxifloxacin-dexlansoprazole therapy plus S. boulardii provide an reliable cure rate of H. pylori in non-ulcer dyspeptic patients in Thailand, independent of CYP2C19 genotype. Probiotic adding also decreased side effects during the treatment.

Keywords: Triple therapy, probiotic supplement, Helicobacter pylori eradication, Thailand

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a spiral shaped, microaerophilic, gram negative bacterium, was first identified by Marshall and Warren in 1984 (Marshall and Warren, 1984). This organism is an acceptable cause of precancerous lesions of gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (Vilaichone and Mahachai, 2001; Vilaichone et al., 2006; Srinarong et al., 2014). Many prior researches has demonstrated link between H. pylori and gastric adenocarcinoma (Karami et al., 2013; Basiri et al., 2014; Parsonnet et al., 1991; Uemura et al., 2001; Demirel et al., 2013; Mahachai et al., 2011). The International Agency for Research in Cancer classified H. pylori as a type I carcinogen and previous studies has found that H. pylori treatment could be reduced the incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma (Ford et al., 2014; Abebaw et al., 2014).

Recently, H. pylori treatment failure has become a major problem. High commonly used antibiotics, CYP2C19 genotype, and side-effects from regimen are common causes of treatment failure. Standard triple therapy is no longer used as first-line treatment in many countries (Chey and Wong, 2007). Moxifloxacin-based triple therapy has been shown to be good H. pylori eradication with minor side-effects in some previous studies (Nista et al., 2005; Bago et al., 2007; Sacco et al., 2010). For first-line treatment of H. pylori, moxifloxacin-based triple therapy also had higher cure rate compared with standard triple therapy (Nista et al., 2005). Interestingly, many probiotic (eg. Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus paracasei, Bifidobacterium lactis, and Saccharomyces boulardii) have demonstrated the positive effect to H. pylori treatment in recent studies (Mirzaee and Rezahosseini, 2012; Zheng et al., 2013; Srinarong et al., 2014; Szajewska et al., 2015).

The aim of our present study is to evaluate the combination of drugs and optimal duration for H. pylori eradication. In this prospective double-blind randomized trial, we demonstrated H. pylori eradication by using moxifloxacin-dexlansoprazole based triple therapy with or without probiotic supplement for 7 or 14 days. The effects of antibiotic resistance, CYP2C19 and CagA genotyping were also tested.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Patients age more than 18 years who underwent upper GI endoscopy for evaluation of chronic dyspepsia at Thammasat University Hospital between December 2015 and December 2016 were included. Patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia, defined as normal upper GI endoscopy or only mild gastritis, were included in the study. Those with a history of prior H. pylori eradication, currently receiving PPI, H2-blocker, bismuth group or any kinds of antibiotics within 4 weeks before this study, receiving anticoagulants or NSAIDs, and other serious underlying diseases (eg. heart diseases, major illness, or cancers) were excluded. Informed consent was applied for all patients.

The diagnosis of H. pylori infection

4 biopsies from antrum of stomach were done during upper GI endoscopy for rapid urease test, H. pylori culture, histological examination, CYP2C19 genotype, Epsilometer test (E-test) or GenoType®HelicoDR. The positive H. pylori infection was defined as: positive H. pylori culture, or two positive tests (rapid urease test and histology). The CYP2C19 genotyping were demonstrated as: rapid metabolizer (RM), intermediate metabolizer (IM), or poor metabolizer (PM). CagA genotyping were performed in all cases.

Therapeutic regimens

All patients were randomized into 4 groups by using a computer-generated list: (1) 7-day moxifloxacin-based triple therapy with probiotic, (2) 7-day moxifloxacin-based triple therapy with placebo, (3) 14-day moxifloxacin-based triple therapy with probiotic, or (4) 14-day moxifloxacin-based triple therapy with placebo. Moxifloxacin-based triple therapy consisted of moxifloxacin 400mg once daily, dexlansoprazole 60mg twice daily, and long acting clarithromycin MR 1g once daily. Probiotic was Saccharomyces boulardii in capsule (bioflor®) dosed 282.5mg twice daily, whereas placebo was exactly identical capsule without probiotic.

Post-therapy follow-up

13C-UBT was applied to assess H. pylori eradication in all individual after treatment for at least 4 weeks. Successful of treatment defined as negative 13C- UBT. Pill count was done, and drug consumption greater than 90% defined as well adherent. Personal interview with open-ended questions by questionnaire were used to assess adverse events. The likelihood side-effects listed in questionnaires were nausea, vomiting, skin rashes, bitter taste, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, headache and palpitation. Therapy-related side effects were defined as new symptoms and worsening of pre-existing symptoms during the treatment period. Side effects severe enough to disrupt patients’ activity from normal life and require hospitalizing were defined as serious events.

Statistical analysis

The eradication rate of treatment regimen was estimated to be more than 90%. Treatment success was defined as a cure rate more than 95% (grade A) as described before (Graham et al., 2007), and failure as a cure rate of less than 90% per protocol. Chi-squared, Fisher’s exact, and student’s t-test were used to compare the demographic characteristics and frequencies of side-effects where appropriate. Statistic significant defined as P-value less than 0.05. This study was approved by our local ethics committee, and was conducted according to good clinical practice guideline, as well as Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Total of 108 patients were enrolled in this study, 56.5% were male with a mean age of 54.2 years. 108 patients were randomized in to 4 groups and the baseline demographic data were not different between 2 regimens as in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Data of All Patients

| Characteristic data | 7-day regimen | 14-day regimen |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 54) | (n=54) | |

| Age (years) | 55 | 53.3 |

| Male no. (%) | 32 (59.3%) | 29 (53.7%) |

| Underlying disease no. (%) | ||

| Hypertension | 4 (7.4%) | 5 (9.3%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 4 (7.4%) | 5 (9.3%) |

| Smoking no. (%) | 7 (13%) | 8 (14.8%) |

| Alcohol consumption no. (%) | 11 (20.4%) | 11 (20.4%) |

*P-value, not significant for all variables

Eradication of H. pylori infection

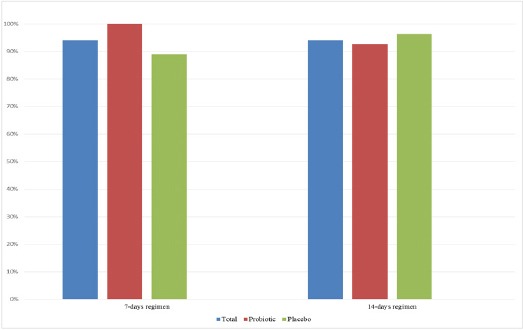

Both intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses results were similar because no patients drop out during study period. Eradication rates in 7-day regimen plus probiotic supplement were 100% compared with 88.9% in 7-day regimen plus placebo (p-value=0.24), as in Figure 1. The eradication rate of 14-day regimen plus probiotic and placebo were 92.6%, and 96.3%, respectively (p-value=1.000). However, there was no different in eradication rates between those with probiotic and placebo or those received 7- and 14-days regimens (96.3% vs. 92.6%; p=0.68, and 94.4% vs. 94.4%; p-value=1, respectively).

Figure 1.

The Eradication Rates According to Treatment Regimens

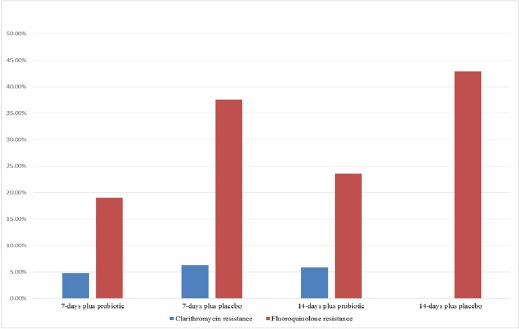

Antibiotic susceptibility tests were performed in 68 strains (27 from E-test and 41 from GenoType®HelicoDR), which have been demonstrated in 4.4% of clarithromycin resistant, 18.5% of metronidazole resistant, and 29.4% of fluoroquinolone resistant strains (Figure 2). There were no amoxicillin or tetracycline resistant strains in our study. CYP2C19 genotype tests were performed in 103 cases (51 from 7-days, and 52 from 14-days regimens). The CYP2C19 genotyping revealed 42.7% RM, 46.6% IM, and 10.7% PM. The prevalence of CYP2C19 genotype was not different in all groups (Table 2). CagA genes were positive in all patients.

Figure 2.

The Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistance Determined by E-test and Genotype HelicoDR

Table 2.

Results of CYP2C19 Genotype and Eradication Rate (Shown in Parentsese) According to Treatment Regimens

| CYP2C19 genotype (n=103) | 7-day plus probiotic (n=26) | 7-day plus placebo (n=25) | 14-day plus probiotic (n=26) | 14-day plus placebo (n=26) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM no. (n=11; 10.7%) | 3 (100%) | 1 (0.00%) | 5 (100%) | 2 (100%) |

| IM no. (n=48; 46.6%) | 12 (100%) | 13 (92.3%) | 9 (88.9%) | 14 (92.9%) |

| RM no. (n=44; 42.7%) | 11 (100%) | 11 (90.9%) | 12 (91.7%) | 10 (100%) |

*number in parenteses are eradication rates

Adverse events

Common adverse events included diarrhea, bitter taste, nausea, and abdominal discomfort. All adverse events were demonstrated in Table 3. Two patients in 14-day regimen plus placebo had severe nausea and vomiting requiring hospital visit. One patient in 14-day regimen plus placebo reported mild palpitation without abnormal ECG, and this patient had completed the treatment regimen under closed observation by cardiologist without any further adverse events. Interestingly, patients in probiotic group had lower overall incidence of nausea, abdominal discomfort, bitter taste, and diarrhea than in placebo group (7.4% vs. 22.22%; p=0.028, 0.00% vs. 14.8%; p=0.003, 35.2% vs. 70.4%; p=0.0002, and 0.00% vs. 9.3%; p=0.028, respectively). Further analysis also showed that the incidence of nausea, abdominal discomfort, and bitter taste was significantly lower in 14-day regimen with probiotic than placebo group (11.1% vs. 33.3%; p=0.049, 0% vs. 25.9%; p=0.005, and 33.3% vs. 81.48%; p=0.0004, respectively). No patient experienced any major side effects.

Table 3.

Adverse Events According to 4 Treatment Regimens

| Adverse events | 7-day plus probiotic | 7-day plus placebo | P-value | 14-day plus probiotic | 14-day plus placebo | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=27) | (n=27) | (n=27) | (n=27) | |||

| Palpitation | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1 | 0.00% | 3.70% | 0.5 |

| Nausea | 3.70% | 11.10% | 0.305 | 11.10% | 33.30% | 0.0496 |

| Discomfort* | 0.00% | 3.70% | 0.5 | 0.00% | 25.90% | 0.005 |

| Diarrhea | 0.00% | 3.70% | 0.5 | 0.00% | 14.80% | 0.0554 |

| Bitter taste | 37.00% | 59.30% | 0.086 | 33.30% | 81.48% | 0.0004 |

abdominal discomfort

Discussion

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the world with more than 70% of cases occurs in East Asia and developing word (Hajmanoochehri et al., 2013; Ford et al., 2014;Vilaichone et al., 2001; Vilaichone et al., 2006; Rahman et al., 2014). The results of treatment are grave because most cases are presented at advanced stage. Infection with H. pylori causes chronic gastritis, gastric atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia, which can lead to development of gastric cancer. A systematic review has confirmed that individuals who tested positive for H. pylori were at least three times more likely to develop gastric cancer (Forman et al., 1991; Nomura et al., 1991; Parsonnet et al., 1991). Currently, H. pylori infection found more than 50% of world population mostly in Asia and africa (Abebaw et al., 2014). All consensus reports from Asia-pacific and western countries suggested eradicating H. pylori infection to prevent gastric cancer (Fock et al., 2009; Malfertheiner et al., 2012). The eradication rate of H. pylori by standard triple therapy was declining to unacceptable results (less than 70%) worldwide including ASEAN countries (Vilaichone et al., 2006; Graham, 2009).

Fluoroquinolones have been evaluated to be a good alternative choice (Gisbert and Morena, 2006; Graham and Shiotani, 2012). Previous studies have demonstrated that longer duration of fluoroquinolone triple therapy up to 14 days increased eradication rate to 95% (Miehlke et al., 2011; Prapitpaiboon et al., 2015). In our study, the eradication rate of 14-days moxifloxacin-dexlansoprazole triple therapy were more than 90% in both probiotic and placebo group, despite higher fluoroquinolone resistance in the study population.

Probiotics are live microorganisms which provide benefit to human health, both for digestive tract and immune system (Fuller, 1991; Otles et al., 2003). Prior studies demonstrated that probiotic could be decreased adverse events of the H. pylori eradication regimens. The possible explanation is that adding probiotics may restore the equilibrium of intestinal floras previously altered by combination of antibiotics in the treatment regimen (Armuzzi et al., 2001; Srinarong et al., 2014). In addition, probiotics also enhances the H. pylori eradication (Sheu et al., 2006; Du et al., 2012; Srinarong et al., 2014). S. boulardii is nonpathogenic yeast. Recent studies have demonstrated that the addition of S. boulardii to standard triple therapy significantly increased the eradication rate and decreased some therapy-related side effect, particularly of diarrhea, and nausea (Zojaji et al., 2013; Szajewska et al., 2015). Our study had similar result, of which the incidence of nausea, bitter taste, abdominal discomfort, and diarrhea were lower in probiotic group. However, there was no statistical significant difference in eradication rate between probiotic and placebo group.

In summary, 7-day moxifloxacin-dexlansoprazole therapy plus S. boulardii provide a reliable cure rate of H. pylori infection in non-ulcer dyspeptic patients in Thailand, independent of CYP2C19 genotype. Probiotic adding also decreased side effects during the treatment.

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by the Research Funds of Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University Hospital, Gastroenterology Association of Thailand (GAT) and the National Research University Project of Thailand, Office of the Higher Education Commission, Thailand.

References

- Abebaw W, Kibret M, Abera B. Prevalence and risk factors of H. pylori from dyspeptic patients in northwest Ethiopia: a hospital based cross-sectional study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:4459–63. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.11.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armuzzi A, Cremonini F, Bartolozzi F, et al. The effect of oral administration of Lactobacillus GG on antibiotic-associated gastrointestinal side-effects during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:163–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bago P, Vcev A, Tomic M, et al. High eradication rate of Hpylori with moxifloxacin-based treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2007;119:372–8. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0807-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basiri Z, Safaralizadeh R, Bonyadi MJ, et al. Helicobacter pylori vacA d1 genotype predicts risk of gastric adenocarcinoma and peptic ulcers in northwestern Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:1575–9. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.4.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chey WD, Wong BC. American college of gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirel BB, Akkas BE, Vural GU. Clinical factors related with helicobacter pylori infection--is there an association with gastric cancer history in first-degree family members? Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1797–802. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.3.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du YQ, Su T, Fan JG, et al. Adjuvant probiotics improve the eradication effect of triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6302–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, et al. Second Asia-pacific consensus guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2014;348:g3174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F, et al. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ. 1991;302:1302–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6788.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller R. Probiotics in human medicine. Gut. 1991;32:439–42. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.4.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisbert JP, Morena F. Systematic review and meta-analysis: levofloxacin-based rescue regimens after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DY. Efficient identification and evaluation of effective Helicobacter pylori therapies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:145–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. A report card to grade Helicobacter pylori therapy. Helicobacter. 2007;12:275–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham DY, Shiotani A. Which therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection? Gastroenterology. 2012;143:10–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajmanoochehri F, Mohammadi N, Nasirian N, et al. Patho-epidemiological features of esophageal and gastric cancers in an endemic region: a 20-year retrospective study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:3491–7. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.6.3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karami N, Talebkhan Y, Saberi S, et al. Seroreactivity to Helicobacter pylori antigens as a risk indicator of gastric cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1813–7. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.3.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahachai V, Sirimontaporn N, Tumwasorn S, et al. Sequential therapy in clarithromycin-sensitive and -resistant Helicobacter pylori based on polymerase chain reaction molecular test. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:825–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miehlke S, Krasz S, Schneider-Brachert W, et al. Randomized trial on 14 versus 7 days of esomeprazole, moxifloxacin, and amoxicillin for second-line or rescue treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2011;16:420–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaee V, Rezahosseini O. Randomized control trial: Comparison of triple therapy plus probiotic yogurt vs. standard triple therapy on Helicobacter Pylori eradication. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14:657–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nista EC, Candelli M, Zocco MA, et al. Moxifloxacin-based strategies for first-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1241–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1132–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otles S, Cagindi O, Akcicek E. Probiotics and health. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2003;4:369–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prapitpaiboon H, Mahachai V, Vilaichone RK. High efficacy of Levofloxacin-Dexlansoprazole-based quadruple therapy as a first line treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:4353–6. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.10.4353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman R, Asombang AW, Ibdah JA. Characteristics of gastric cancer in Asia. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4483–90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i16.4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco F, Spezzaferro M, Amitrano M, et al. Efficacy of four different moxifloxacin-based triple therapies for first-line H. pylori treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:110–4. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu BS, Cheng HC, Kao AW, et al. Pretreatment with Lactobacillus- and Bifidobacterium-containing yogurt can improve the efficacy of quadruple therapy in eradicating residual Helicobacter pylori infection after failed triple therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:864–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinarong C, Siramolpiwat S, Wongcha-um A, et al. Improved eradication rate of standard triple therapy by adding bismuth and probiotic supplement for Helicobacter pylori treatment in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:9909–13. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.22.9909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szajewska H, Horvath A, Kolodziej M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Saccharomyces boulardii supplementation and eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1237–45. doi: 10.1111/apt.13214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaichone RK, Mahachai V. Current management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaichone RK, Mahachai V, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori diagnosis and management. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2006;35:229–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Lyu L, Mei Z. Lactobacillus-containing probiotic supplementation increases Helicobacter pylori eradication rate: evidence from a meta-analysis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:445–53. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082013000800002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zojaji H, Ghobakhlou M, Rajabalinia H, et al. The efficacy and safety of adding the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardiito standard triple therapy for eradication of H.pylori: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6:99–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]