Abstract

Objective

Coronary angiography (CAG) for survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) enables early identification of coronary artery disease and revascularization, which might improve clinical outcome. However, little is known for the role of CAG in patients with initial non-shockable cardiac rhythm.

Methods

We investigated clinical outcomes of successfully resuscitated 670 adult OHCA patients who were transferred to 27 hospitals in Cardiac Arrest Pursuit Trial with Unique Registration and Epidemiologic Surveillance (CAPTURES), a Korean nationwide multicenter registry. The primary outcome was 30-day survival with good neurological outcome. Propensity score matching and inverse probability of treatment weighting analyses were performed to account for indication bias.

Results

A total of 401 (60%) patients showed initial non-shockable rhythm. CAG was performed only in 13% of patients with non-shockable rhythm (53 out of 401 patients), whereas more than half of patients with shockable rhythm (149 out of 269 patients, 55%). Clinical outcome of patients who underwent CAG was superior to patients without CAG in both non-shockable (hazard ratio (HR) = 3.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 2.5–5.2) and shockable rhythm (HR = 3.7, 95% CI = 2.5–5.4, p < 0.001, all). Further analysis after propensity score matching or inverse probability of treatment weighting showed consistent findings (HR ranged from 2.0 to 3.2, p < 0.001, all).

Conclusions

Performing CAG was related to better survival with good neurological outcome of OHCA patients with initial non-shockable rhythms as well as shockable rhythms.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is a major public health burden and associated with high morbidity and mortality rates worldwide [1]. Coronary artery disease is the most common cause of adult OHCA [2, 3]. Therefore, improved survival among OHCA survivor who underwent coronary angiography (CAG) can be easily anticipated because CAG enables immediate diagnosis and appropriate treatment including revascularization [4, 5]. The clinical benefit of CAG has been studied mostly for adult OHCA patients with initial shockable rhythm such as ventricular tachyarrhythmia [4, 5]. However, it is not well known whether performing CAG has clinical benefit in OHCA patient with initial non-shockable rhythms including pulseless electrical activity (PEA) and asystole.

Most improvement in the clinical outcome of OHCA has been derived from improved survival in OHCA with initial shockable rhythm [6, 7], whereas OHCA with initial non-shockable rhythm still suffers from little improvement of very poor clinical outcome [8–11]. In addition, the proportion of initial non-shockable rhythm to the initial shockable rhythm has increased consistently [12–14]. The aim of this study was to assess the association between CAG and clinical outcomes in adult non-shockable OHCA from Korean nationwide multicenter OHCA registry. Propensity score matching and inverse probability of treatment weighting analyses were applied to minimize indication bias.

Methods

Data source and study population

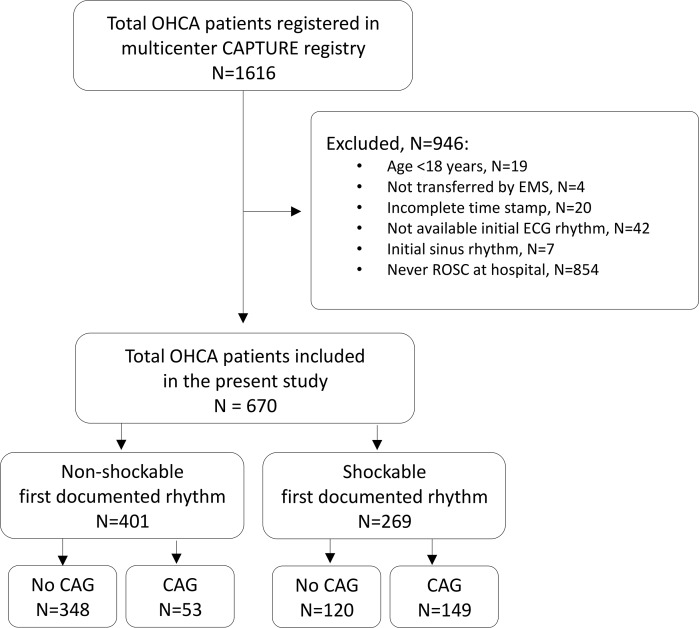

The Cardiac Arrest Pursuit Trial with Unique Registration and Epidemiologic Surveillance (CAPTURES) project was a Korean multicenter observational study conducted from January to December 2014 at 27 emergency departments (EDs) (9 level 1 EDs and 18 level 2 EDs). This project aimed to identify the risk factors of OHCA and to evaluate the prognostic factors in long-term follow up. The CAPTURES project included OHCA patients who were transported to the study EDs with resuscitation efforts and had a presumed cardiac etiology as identified by emergency physicians in each ED. OHCA patients with definite non-cardiac etiology such as trauma, drowning, hanging, poisoning, asphyxia, burn, hemorrhagic or ischemic stroke, or terminal illness were excluded. Clinical data were collected at each study ED and transferred to the central data server using EpiData version 3.1 (The EpiData Association, Denmark, Europe). A total of 1616 OHCA patients were registered in CAPTURES project. After exclusion of patients who could not achieve a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC, N = 854), were not transferred by emergency medical service or lacks documentation (N = 66), age < 18 (N = 19), and initial sinus rhythm (N = 7), 670 OHCA patients consisting of 401 initial non-shockable rhythm and 269 initial shockable rhythm were enrolled in the analysis (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Study population flow.

Abbreviations: OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; CAPTURES, Cardiac Arrest Pursuit Trial with Unique Registration and Epidemiologic Surveillance; EMS, emergency medical service; ECG, electrocardiography; ROSC, return of spontaneous circulation; CAG, coronary angiography.

Clinical variables

Pre-hospital patient-level data included age, gender, location of arrest (public, home or healthcare), bystander witness, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), prehospital defibrillation, ED arrival at weekend or business hour, and first documented cardiac rhythm dichotomized as non-shockable or shockable rhythm. We also calculated time interval of response time (from EMS call time to EMS arrival time) and transfer time (from EMS arrival time to ED arrival time) based on timestamp of the medical record.

Cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidemia were assessed if available. In-hospital data included intubated status, use of intravenous inotropic agent, CAG, revascularization by percutaneous coronary revascularization (PCI), mechanical circulatory support including intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), implantation of implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) and targeted temperature management (TTM).

Study outcome

The primary outcome was survival with a favorable neurological outcome at discharge measured by the Glasgow-Pittsburgh cerebral performance category (CPC) scores at 30 days. Good and poor neurological outcome was defined by CPC = 1 or 2 and CPC = 3 to 5, respectively. The secondary outcome was all-cause death within 30 days.

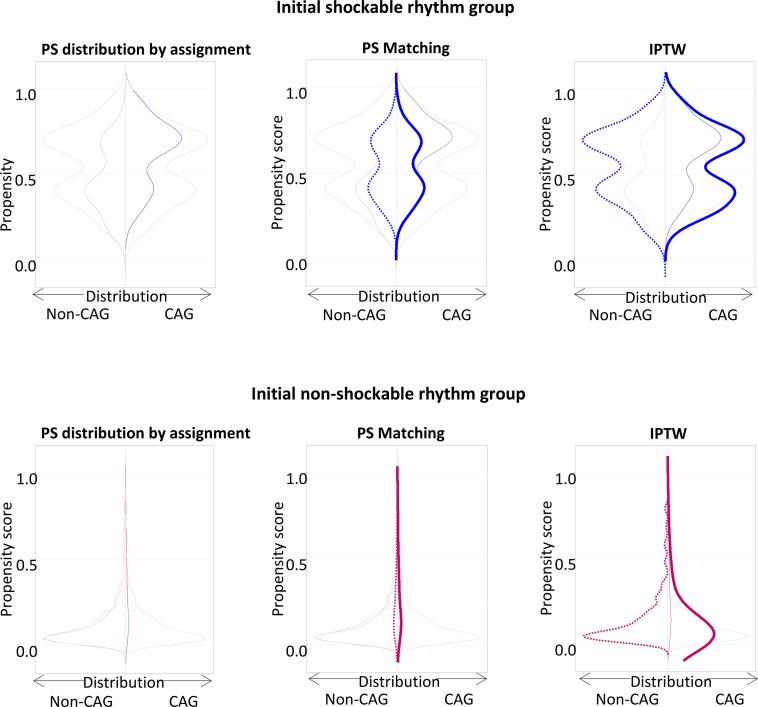

Statistical analysis

Continuous and categorical data are presented as median with 1st–3rd quartile and number (proportion, %), respectively, and tested by Mann Whitney U or chi-square test, appropriately. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for clinical outcomes between groups. Comparison was adjusted by propensity score matching (PSM) and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) to reduce indication bias. For PSM analysis, 1:1 matched pairs were selected based on the predicted probability of being assigned to CAG in non-shockable and shockable OHCA. Non-parsimonious model was developed including clinical characteristics variables; age, gender, location of arrest, bystander witness and resuscitation, prehospital defibrillation, ED visit at business hour, intubated status, use of intravenous inotropic agent, and TTM. Discrimination and calibration performance of the model was tested by c-statistics (0.794 for non-shockable rhythm group, 0.733 for shockable rhythm group) and Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics (chi-square = 9.38, df = 8, p = 0.31 for non-shockable rhythm group, chi-square = 2.04, df = 8, p = 0.98 for shockable rhythm group), respectively. The distributions of propensity score in PSM and IPTW analyses were shown in Fig 2. Statistical significance was defined by two-tailed p value < 0.001. R version 3.4 (R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for all computational analyses.

Fig 2. PS matching and IPTW analyses for adult OHCA patients according to initial ECG rhythm.

Abbreviations: PS, propensity score; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; ECG, electrocardiography; CAG, coronary angiography.

Ethics statements

The study protocol was approved by all Institutional Review Boards of 27 participating hospitals with waiver of informed consent. This study was financially supported by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013–2014).

Results

Clinical characteristics

Compared to patients with shockable rhythm, patients with non-shockable rhythm were older (median age 67 versus 56 years), more likely to be female (34 versus 19%), and showed higher frequency of clinical risk factors (p < 0.001, all). Patients with non-shockable rhythm were less likely to be found at public location (23 versus 47%), be witnessed (68 versus 81%), and receive bystander CPR (39 versus 60%, p < 0.001, all). Time from EMS call to EMS arrival was not different between two groups but time from EMS arrival to ED transfer was shorter in non-shockable rhythm group compared to shockable rhythm (19 versus 24 minutes). Patients with non-shockable rhythm underwent more intubation (96 versus 87%), use of inotropics (82 versus 62%), but less CAG (13 versus 55%) and TTM (22 versus 45%, p < 0.001, all) (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of adult OHCA patients according to initial ECG rhythm.

| Non-shockable rhythm (N = 401) |

Shockable rhythm (N = 269) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median [IQR] | 67 [53, 77] | 56 [47, 67] | <0.001 |

| Female, N(%) | 136 (34) | 52 (19) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, N(%) | 169 (42) | 95 (35) | 0.009 |

| DM, N(%) | 98 (24) | 46 (17) | 0.005 |

| Dyslipidemia, N(%) | 21 (5) | 20 (7) | 0.077 |

| Arrest location, N(%) | <0.001 | ||

| Home | 249 (62) | 111 (41) | |

| Public | 94 (23) | 127 (47) | |

| Healthcare | 50 (13) | 20 (7) | |

| Unknown | 8 (2) | 11 (4) | |

| Bystander witnessed, N(%) | 272 (68) | 217 (81) | <0.001 |

| Bystander CPR, N(%) | 156 (39) | 161 (60) | <0.001 |

| First documented rhythm, N(%) | |||

| Asystole | 251 (63) | ||

| PEA | 110 (27) | ||

| Unknown | 40 (10) | ||

| Prehospital defibrillation, N(%) | 33 (8) | 251 (93) | <0.001 |

| Min to response*, median [IQR] | 6.0 [5.0, 9.0] | 6.0 [5.0, 8.0] | 0.493 |

| Min to transfer*, median [IQR] | 19.0 [13.0, 28.0] | 24.0 [15.0, 59.0] | <0.001 |

|

ED visit at working hour

(8 a.m. to 5 p.m.), N(%) |

111 (28) | 68 (25) | 0.549 |

| ED visit at weekend, N(%) | 100 (25) | 100 (37) | 0.001 |

| Hospital Course | |||

| Intubation, N(%) | 383 (96) | 235 (87) | <0.001 |

| Use of inotropics, N(%) | 329 (82) | 167 (62) | <0.001 |

| CAG, N(%) | 53 (13) | 149 (55) | <0.001 |

| PCI, N(%) | 20 (5) | 54 (20) | <0.001 |

| IABP, N(%) | 4 (1) | 18 (7) | <0.001 |

| ECMO, N(%) | 12 (3) | 20 (7) | 0.014 |

| Implantation of ICD, N(%) | 2 (1) | 29 (11) | <0.001 |

| Temporary pacing, N(%) | 4 (1) | 7 (3) | 0.196 |

| TTM, N(%) | 89 (22) | 120 (45) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; ECG, electrocardiography; IQR, interquartile range; DM, diabetes mellitus; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; ED, emergency department; CAG, coronary angiography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; TTM, targeted temperature management

*Min to response, minutes from EMS call to EMS arrival; Min to transfer, minutes from EMS arrival to ED arrival.

When these clinical characteristics were classified by CAG, patients with non-shockable rhythm who underwent CAG were more likely to be found at public location (45 versus 20%), receive prehospital defibrillation (26% versus 6%), and TTM (43 versus 19%, p < 0.001, all). Patients with shockable rhythm who underwent CAG were less likely to receive an advanced airway (81 versus 96%) and more likely to receive TTM (55 versus 32%, p < 0.001, all). Among patients who underwent CAG, the frequency of ST-elevation ECG (21% versus 18%, p = 0.68) and the frequency of revascularization by PCI (38% versus 36%, p = 0.28) was not different between non-shockable and shockable rhythm (Table 2).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of adult OHCA patients according to initial ECG rhythm and CAG.

| Non-shockable rhythm | Shockable rhythm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-CAG N = 348 |

CAG N = 53 |

p-value | Non-CAG N = 120 |

CAG N = 149 |

p-value | |

| Age, median [IQR] | 69 [54, 79] | 57 [53, 69] | 0.001 | 58 [45, 70] | 54 [48, 65] | 0.444 |

| Female, N(%) | 128 (37) | 8 (15) | 0.003 | 32 (27) | 20 (13) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension, N(%) | 147 (42) | 22 (42) | 0.83 | 35 (29) | 60 (40) | 0.112 |

| DM, N(%) | 85 (24) | 13 (25) | 0.872 | 22 (18) | 24 (16) | 0.295 |

| Dyslipidemia, N(%) | 18 (5) | 3 (6) | 0.83 | 6 (5) | 14 (9) | 0.257 |

| Arrest location, N(%) | <0.001 | 0.348 | ||||

| Home | 231 (66) | 18 (34) | 50 (42) | 61 (41) | ||

| Public | 70 (20) | 24 (45) | 59 (49) | 68 (46) | ||

| Healthcare | 42 (12) | 8 (15) | 9 (8) | 11 (7) | ||

| Unknown | 5 (1) | 3 (6) | 2 (2) | 9 (6) | ||

| Bystander witnessed, N(%) | 229 (66) | 43 (81) | 0.039 | 100 (83) | 117 (79) | 0.402 |

| Bystander CPR, N(%) | 133 (38) | 23 (43) | 0.569 | 63 (53) | 98 (66) | 0.037 |

| First documented rhythm, N(%) | <0.001 | |||||

| Asystole | 230 (66) | 21 (40) | ||||

| PEA | 89 (26) | 21 (40) | ||||

| Unknown | 29 (8) | 11 (21) | ||||

| ST-elevation in post-ROSC ECG | 17 (5) | 11 (21) | <0.001 | 5 (4) | 27 (18) | <0.001 |

| Prehospital defibrillation, N(%) | 19 (6) | 14 (26) | <0.001 | 110 (92) | 141 (95) | 0.47 |

| Min to response*, median [IQR] | 6.0 [5.0, 8.0] | 7.0 [5.0, 10.0] | 0.274 | 6.0 [5.0, 8.0] | 6.0 [5.0, 8.0] | 0.735 |

| Min to transfer*, median [IQR] | 19.0 [14.0, 27.0] | 18.0 [13.0, 37.0] | 0.828 | 23.0 [15.0, 55.3] | 24.0 [15.0, 71.0] | 0.6 |

|

ED visit at working hour

(8 a.m. to 5 p.m.), N(%) |

101 (29) | 10 (19) | 0.169 | 31 (26) | 37 (25) | 0.963 |

| ED visit at weekend, N(%) | 89 (26) | 11 (21) | 0.558 | 45 (38) | 55 (37) | 1 |

| Hospital Course | ||||||

| Intubation, N(%) | 331 (95) | 52 (98) | 0.531 | 115 (96) | 120 (81) | <0.001 |

| Use of inotropics, N(%) | 285 (82) | 44 (83) | 0.995 | 77 (64) | 90 (60) | 0.613 |

| PCI, N(%) | 0 (0) | 20 (38) | <0.001 | 0 (0) | 54 (36) | <0.001 |

| IABP, N(%) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (6) | 0.003 | 0 (0) | 18 (12) | <0.001 |

| ECMO, N(%) | 6 (2) | 6 (11) | 0.001 | 2 (2) | 18 (12) | 0.003 |

| Implantation of ICD, N(%) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 0.01 | 8 (7) | 21 (14) | 0.079 |

| Temporary pacing, N(%) | 2 (0.6) | 2 (4) | 0.15 | 3 (3) | 4 (3) | 1 |

| TTM, N(%) | 66 (19) | 23 (43) | <0.001 | 38 (32) | 82 (55) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; ECG, electrocardiography; CAG, coronary angiography; IQR, interquartile range; DM, diabetes mellitus; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; ED, emergency department; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; TTM, targeted temperature management

*Min to response, minutes from EMS call time to EMS arrival time; Min to transfer, minutes from EMS arrival time to ED arrival time.

Comparisons of clinical outcomes according to initial electrocardiogram rhythm and CAG

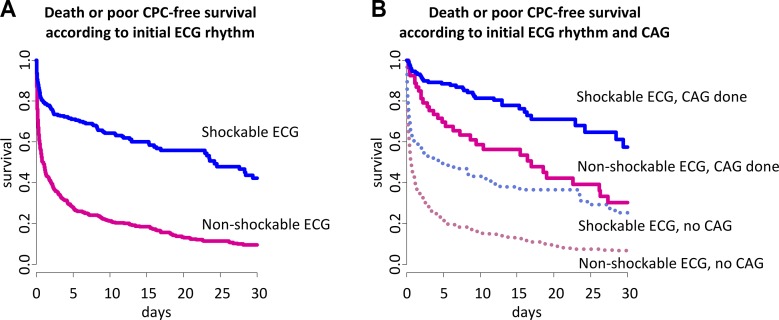

Patients with shockable rhythm showed much higher 30-day survival with good neurological outcome compared with patients with non-shockable rhythm (unadjusted HR = 3.2, 95% CI = 2.6–3.9, p < 0.001) (Fig 3A). Intriguingly, performing CAG is associated with better clinical outcome in both non-shockable and shockable rhythm group (Fig 3B). As shown in Table 3, the unadjusted 30-day survival with good neurological outcome was more than 3-fold higher in patients underwent CAG compared with patients without CAG irrespective of initial rhythm (non-shockable rhythm group, HR = 3.6 (95% CI = 2.5–5.2); shockable rhythm group, HR = 3.7 (95% CI = 2.5–5.4), respectively, p < 0.001, all). After PSM or IPTW adjustment, the 30-day survival with good neurological outcome was still more than 2-fold higher in patients underwent CAG compared with patients without CAG irrespective of initial rhythm (PSM, non-shockable rhythm group, HR = 2.4 (95% CI = 1.5–3.8); shockable rhythm group, HR = 2.3 (95% CI = 1.5–3.7), respectively, p < 0.001, all; IPTW, non-shockable rhythm group, HR = 2.0 (95% CI = 1.5–2.7); shockable rhythm group, HR = 3.2 (95% CI = 2.2–4.7), respectively, p < 0.001, all). The superior clinical outcome of patients with CAG was also maintained when analyzed with the 30-day all-cause death (Table 3).

Fig 3. Unadjusted survival curves for adult OHCA patients.

(A) Unadjusted survival curves according to initial ECG rhythm. (B) Unadjusted survival curves according to CAG. Abbreviations: OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; ECG, electrocardiography; CAG, coronary angiography; CPC, cerebral performance category.

Table 3. Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for adult OHCA patients with initial non-shockable or shockable rhythm.

| Initial shockable rhythm | ||||||||

| Clinical outcome | Crude (N = 269) | PS match (85 pairs) | IPTW | |||||

| Non-CAG (N = 120) |

CAG (N = 149) |

HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Survival with good CPC at 30 day | 35 (29) | 110 (74) | 3.7 (2.5–5.4) | <0.001 | 2.3 (1.5–3.7) | <0.001 | 3.2 (2.2–4.7) | <0.001 |

| Survival at 30 day | 49 (41) | 121 (81) | 4.4 (2.8–6.8) | <0.001 | 2.6 (1.5–4.3) | <0.001 | 3.5 (2.3–5.5) | <0.001 |

| Initial non-shockable rhythm | ||||||||

| Clinical outcome | Crude (N = 401) | PS match (46 pairs) | IPTW | |||||

| Non-CAG (N = 348) |

CAG (N = 53) |

HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Survival with good CPC at 30 day | 14 (4) | 19 (36) | 3.6 (2.5–5.2) | <0.001 | 2.4 (1.5–3.8) | <0.001 | 2.0 (1.5–2.7) | <0.001 |

| Survival at 30 day | 61 (18) | 30 (57) | 3.8 (2.5–5.8) | <0.001 | 2.5 (1.4–4.3) | 0.001 | 2.1 (1.5–3.0) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PS, propensity score; IPTW, inverse probability of treatment weighting; CAG, coronary angiography; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CPC, cerebral performance category.

Discussion

In this study based on a nationwide multicenter OHCA registry, we found that patients who underwent CAG after successful ROSC had better short-term survival with favorable neurological status than those who did not. The better clinical outcome of performing CAG was found not only in shockable OHCA but also in non-shockable OHCA. The result was also consistent after PSM and IPTW adjusted analyses.

Prior observational studies have reported that CAG was associated with improved clinical outcomes in OHCA survivors [5, 15–18]. Most previous studies have mainly included OHCA patients with initial shockable rhythm because acute coronary occlusion is a major cause of cardiac arrest with ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia. However, this study separately analyzed OHCA patients with non-shockable and shockable rhythm and then, assessed the association between CAG and clinical outcomes in each rhythm group.

Recent study has reported that an initial shockable rhythm was the strongest indicator of acute coronary occlusion requiring early PCI [19]. CAG enables early identification and revascularization of coronary arterial occlusion, which lead to improve clinical outcomes in shockable OHCA [5]. In this study, PCI was performed in nearly 40% of patients who underwent CAG irrespective of initial rhythm. Performing CAG may have a similarly beneficial effect on clinical outcomes in non-shockable OHCA.

Routine CAG has widely applied in OHCA patients with ST elevation on the post-ROSC electrocardiogram (ECG) because an acute coronary occlusion was found in more than half of these patients [20] and an early coronary revascularization improved survival and neurological outcome in these patients who underwent CAG with PCI [21]. However, several studies showed a high incidence of significant coronary occlusion in OHCA patients without ST elevation on post-ROSC ECG, ranging from 26% to 58% and an improved survival in these patients who underwent CAG with PCI [18, 19, 22, 23]. Thus, it is difficult to assess an acute coronary occlusion as the cause of arrest using post-ROSC ECG in OHCA setting because it lacks sensitivity and specificity to predict an acute coronary occlusion [22–24]. According to the 2015 American Heart Association guidelines, CAG is recommend for all patients with ST elevation and for unstable patients without ST elevation on post-ROSC ECG after OHCA of suspected cardiac cause [25]. The 2014 European Society of Cardiology guidelines on myocardial revascularization have also recommended a routine immediate CAG in all OHCA survivors without an evident non-coronary cause irrespective of the post-ROSC ECG pattern [26]. One recent large cohort study emphasized the use of routine CAG in OHCA survivors as a standard post-cardiac arrest protocol [19]. Taken together, the present results may support the use of CAG for all OHCA survivors with suspected cardiac cause irrespective of initial cardiac rhythm. Further analysis may be needed to evaluate whether early CAG with revascularization improves clinical outcomes in non-shockable OHCA.

Limitations

The present study has the following limitations. First, the study population size was relatively modest and especially the size of CAG group in non-shockable OHCA was small though this study used a nationwide multicenter registry. Second, post-ROSC ECG was missing in about half of CAPTURES registry. The indication for CAG were not pre-specified. Thus, it was possible that patients with STE on post-ROSC ECG were mainly selected for CAG by clinical assessment of physicians in each institution. It might lead to indication bias. Even PSM and IPTW analyses may be insufficient to count multiple factors such as functional status, comorbidities and family or social factors. Interestingly, INCAR registry, which was conducted in 34 centers in Europe and USA, showed 25% CAG rate for initial non-shockable rhythm, which is similar to 26% in our study [1]. However, to overcome selection or indication bias, further investigation whether early CAG with revascularization improves clinical outcomes in non-shockable OHCA would be required. Third, we used first cardiac rhythm documented by EMS, which did not account for patients’ arrest rhythm and subsequent rhythm changes between EMS arrival and hospital arrival. In this study, CAG group in non-shockable OHCA had more PEA and prehospital defibrillation, which might indicate that they had more changes to subsequent shockable rhythm before hospital arrival. In previous studies, OHCA with initial PEA and the change from non-shockable to shockable rhythm had better clinical outcome than OHCA with initial asystole and without the change from non-shockable to shockable rhythm, respectively [27, 28]. Thus, higher proportion of PEA and prehospital defibrillation might contribute to improved survival of CAG group in non-shockable OHCA. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies analyzed separately non-shockable and shockable rhythm to evaluate the association CAG and survival with good neurological outcome after OHCA. Therefore, our finding is notably significant due to the potential impact of CAG on treatment for OHCA survivors.

Conclusion

In a Korean nationwide multicenter study of OHCA (CAPTURES), CAG was significantly associated with improved survival with good neurological outcome for adult OHCA patients of presumed cardiac cause with initial non-shockable rhythms. It suggests that CAG may be beneficial to adult non-shockable OHCA as well as to shockable OHCA. Further randomized controlled trials would be required to confirm the potential benefit of CAG and early revascularization for adult non-shockable OHCA.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Jin-Ho Choi, Won Chul Cha, and Sang Do Shin are member of Cardiac Arrest Pursuit Trial with Unique Registry and Epidemiologic Surveillance investigators

This study was financially supported by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of the Republic of Korea government (2013–2014). (Grant No. 2013E3300500/ 2014E3300100)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

This study was supported and funded by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2013–2014) (Grant No. 2013E3300500/2014E3300100). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sasson C, Rogers MA, Dahl J, Kellermann AL. Predictors of survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(1):63–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.889576 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang HJ, Kim GW, Kim H, Cho JS, Rho TH, Yoon HD, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a report from the NEDIS-based cardiac arrest registry in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(1):95–103. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.1.95 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4278034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wijesekera VA, Mullany DV, Tjahjadi CA, Walters DL. Routine angiography in survivors of out of hospital cardiac arrest with return of spontaneous circulation: a single site registry. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2014;14:30 doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-14-30 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3944915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camuglia AC, Randhawa VK, Lavi S, Walters DL. Cardiac catheterization is associated with superior outcomes for survivors of out of hospital cardiac arrest: review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2014;85(11):1533–40. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.08.025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vyas A, Chan PS, Cram P, Nallamothu BK, McNally B, Girotra S. Early Coronary Angiography and Survival After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(10):e002321 doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002321 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4603281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F, Weeke P, Hansen CM, Christensen EF, et al. Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2013;310(13):1377–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278483 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, Nitta M, Nagao K, Nonogi H, et al. Nationwide improvements in survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Japan. Circulation. 2012;126(24):2834–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.109496 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallstrom A, Herlitz J, Kajino K, Olasveengen TM. Treatment of asystole and PEA. Resuscitation. 2009;80(9):975–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.05.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saarinen S, Kamarainen A, Silfvast T, Yli-Hankala A, Virkkunen I. Pulseless electrical activity and successful out-of-hospital resuscitation—long-term survival and quality of life: an observational cohort study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2012;20:74 doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-20-74 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3495840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cronberg T, Lilja G, Rundgren M, Friberg H, Widner H. Long-term neurological outcome after cardiac arrest and therapeutic hypothermia. Resuscitation. 2009;80(10):1119–23. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.06.021 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan PS, McNally B, Tang F, Kellermann A, Group CS. Recent trends in survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States. Circulation. 2014;130(21):1876–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009711 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4276415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vayrynen T, Boyd J, Sorsa M, Maatta T, Kuisma M. Long-term changes in the incidence of out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 2011;82(7):825–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.02.030 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berdowski J, Berg RA, Tijssen JG, Koster RW. Global incidences of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and survival rates: Systematic review of 67 prospective studies. Resuscitation. 2010;81(11):1479–87. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.08.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mader TJ, Nathanson BH, Millay S, Coute RA, Clapp M, McNally B, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes stratified by rhythm analysis. Resuscitation. 2012;83(11):1358–62. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.03.033 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waldo SW, Armstrong EJ, Kulkarni A, Hoffmayer K, Kinlay S, Hsue P, et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics and outcomes of cardiac arrest survivors having versus not having coronary angiography. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(9):1253–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.267 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanuttini D, Armellini I, Nucifora G, Carchietti E, Trillo G, Spedicato L, et al. Impact of emergency coronary angiography on in-hospital outcome of unconscious survivors after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(12):1723–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.08.006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldberger JJ, Basu A, Boineau R, Buxton AE, Cain ME, Canty JM Jr., et al. Risk stratification for sudden cardiac death: a plan for the future. Circulation. 2014;129(4):516–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007149 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callaway CW, Schmicker RH, Brown SP, Albrich JM, Andrusiek DL, Aufderheide TP, et al. Early coronary angiography and induced hypothermia are associated with survival and functional recovery after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2014;85(5):657–63. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.12.028 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4117649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dumas F, Bougouin W, Geri G, Lamhaut L, Rosencher J, Pene F, et al. Emergency Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Post-Cardiac Arrest Patients Without ST-Segment Elevation Pattern: Insights From the PROCAT II Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9(10):1011–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.02.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Tejada J, Jurado-Roman A, Rodriguez J, Velazquez M, Hernandez F, Albarran A, et al. Post-resuscitation electrocardiograms, acute coronary findings and in-hospital prognosis of survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2014;85(9):1245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.06.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikolaou NI, Arntz HR, Bellou A, Beygui F, Bossaert LL, Cariou A, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015 Section 8. Initial management of acute coronary syndromes. Resuscitation. 2015;95:264–77. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.030 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dumas F, Cariou A, Manzo-Silberman S, Grimaldi D, Vivien B, Rosencher J, et al. Immediate percutaneous coronary intervention is associated with better survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: insights from the PROCAT (Parisian Region Out of hospital Cardiac ArresT) registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3(3):200–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.913665 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollenbeck RD, McPherson JA, Mooney MR, Unger BT, Patel NC, McMullan PW Jr., et al. Early cardiac catheterization is associated with improved survival in comatose survivors of cardiac arrest without STEMI. Resuscitation. 2014;85(1):88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.07.027 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zanuttini D, Armellini I, Nucifora G, Grillo MT, Morocutti G, Carchietti E, et al. Predictive value of electrocardiogram in diagnosing acute coronary artery lesions among patients with out-of-hospital-cardiac-arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84(9):1250–4. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.04.023 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Connor RE, Al Ali AS, Brady WJ, Ghaemmaghami CA, Menon V, Welsford M, et al. Part 9: Acute Coronary Syndromes: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2015;132(18 Suppl 2):S483–500. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35(37):2541–619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukuda T, Matsubara T, Doi K, Fukuda-Ohashi N, Yahagi N. Predictors of favorable and poor prognosis in unwitnessed out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with a non-shockable initial rhythm. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(3):910–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.057 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrew E, Nehme Z, Lijovic M, Bernard S, Smith K. Outcomes following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest with an initial cardiac rhythm of asystole or pulseless electrical activity in Victoria, Australia. Resuscitation. 2014;85(11):1633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.07.015 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.