Abstract

Background Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is fatal in severe cases of pulmonary hypoplasia. We experienced a fatal case of pulmonary hypoplasia due to CDH, thoracic myelomeningocele (MMC), and thoracic dysplasia. This constellation of anomalies has not been previously reported.

Case Report A male infant with a prenatal diagnosis of thoracic MMC with severe hydrocephalus and scoliosis was born at 36 weeks of gestation. CDH was found after birth and the patient died of respiratory failure due to pulmonary hypoplasia and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn at 30 hours of age despite neonatal intensive care. An autopsy revealed a left CDH without herniation of the liver or stomach into the thoracic cavity, severe hydrocephalus, Chiari malformation type II, MMC with spina bifida from Th4 to Th12, hemivertebrae, fused ribs, deformities of the thoracic cage and legs, short trunk, and agenesis of the left kidney.

Conclusion We speculate that two factors may be associated with the severe pulmonary hypoplasia: decreased thoracic space due to the herniation of visceral organs caused by CDH and thoracic dysplasia due to skeletal deformity and severe scoliosis.

Keywords: pulmonary hypoplasia, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, myelomeningocele, thoracic dysplasia, persistent pulmonary hypertension, Chiari malformation, skeletal deformity

The prognosis of patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) has improved thanks to advanced perinatal management including prenatal diagnosis, scheduled delivery, and gentle ventilation. The most recent nationwide survey in Japan (from January 2006 to December 2010) reported that the survival rate of isolated CDH patients improved to 80%. 1 Nonetheless, fatal CDH cases due to severe pulmonary hypoplasia and persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) still exist. 1

Several studies 1 have reported a high mortality rate for patients with complex, nonisolated or syndromic CDH. The prognosis of patients with CDH complicated with cardiovascular malformation and musculoskeletal or craniofacial defects is poorer than that of patients with isolated CDH. 2 3 In some cases, pulmonary hypoplasia caused by other congenital disorders was associated with a poorer prognosis. 4 5

We herein report a very rare case of fatal CDH associated with thoracic myelomeningocele (MMC) and thoracic dysplasia.

Case Presentation

A 23-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 2, para 0) was referred to our hospital at 21 weeks of gestation due to fetal hydrocephalus, MMC, and cardiac malposition. She had no history of infection, medication, or any other diseases during pregnancy. She also had no family history of congenital disease. There was no consanguineous relationship.

Prenatal sonographic findings at 22 weeks of gestational age revealed only fetal thoracic MMC with enlargement of the anterior and posterior horns of the bilateral ventricles, left scoliosis narrowing the left thoracic space, and dislocation of the fetal heart into the right thorax. The amniotic fluid volume was normal. No further fetal diagnostic tests including a fetal MRI were conducted due to the family's poor economic situation.

A male baby was delivered at 36 weeks and 6 days of gestation by elective cesarean section in accordance with our early delivery protocol for prenatally diagnosed MMC cases with severe hydrocephalus to prevent the progression of the hydrocephalus. His birth weight was 2,996 g (z score; +1.2). At birth, he presented with generalized cyanosis and bradycardia and was unable to breathe on his own. He was immediately intubated and placed on positive-pressure ventilation with 100% oxygen. His heart rate recovered to 130 bpm through resuscitation, but the hypoxia persisted.

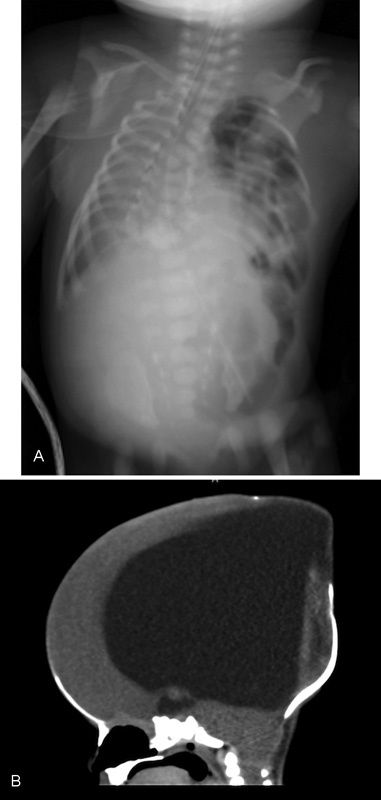

His height and head circumference were 44.0 cm (z score; –1.4) and 42.0 cm (z score; +7.5), respectively. He had an enlarged head circumference, low-set ears, depressed nasal root, short trunk, posterior thoracic MMC, and deformity of the lower limbs. His blood gas analysis on admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) showed severe mixed acidosis (pH 6.982; PCO 2 80.3 mm Hg; and BE –13.6 mmol/L) but the complete blood count and blood chemistry were normal. His chromosomes showed the normal karyotype. Genetic analysis with exome sequencing disclosed no abnormalities. A chest plain radiograph demonstrated herniation of the intestines into the left thoracic cavity, several deformed vertebrae and left ribs, and scoliosis ( Fig. 1A ). Echocardiography showed no structural anomalies, but there was a right-to-left shunt through the ductus arteriosus and the foramen ovale. The McGoon index 6 was 1.17. In addition, a brain ultrasound examination showed severe hydrocephalus. Although we applied high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, inhaled nitric oxide therapy, and vasoactive drugs, his hypoxia did not improve. At about 30 hours of age, the patient died of respiratory failure due to PPHN.

Fig. 1.

Chest plain radiography and computed tomography (CT). ( A ) Chest plain radiography demonstrated herniation of the intestine into the left thoracic cavity, deformity of several left vertebrae and ribs, and scoliosis. ( B ) Brain CT showed hydrocephalus and Chiari malformation type II.

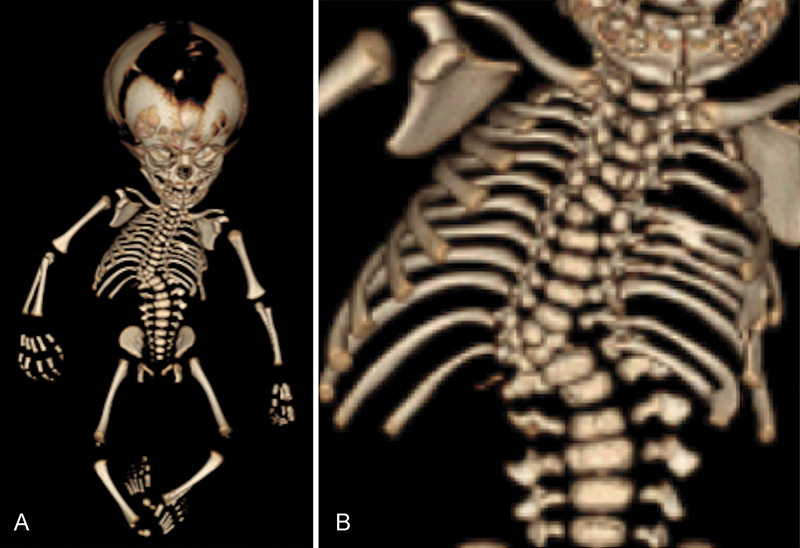

A postmortem computed tomography (CT) showed severe hydrocephalus, Chiari malformation type II, left CDH without herniation of the liver and stomach into the chest cavity, agenesis of the left kidney, and a multiple segmentation anomaly from T4 to T12 ( Fig. 1B ). Fusion and deformity of several left ribs and short stature were observed ( Figs. 2A and 2B ). The overall skeletal deformities were similar to those seen in spondylothoracic dysostosis. We considered Jarcho-Levin syndrome in the differential diagnosis. However, the severity of the rib fusion was insufficient for a definitive diagnosis of this syndrome.

Fig. 2.

Autopsy imaging . ( A ) Postmortem computed tomography showed multiple segmentation anomalies from T4 to T12 and deformity of the lower limbs. ( B ) Fusion of several left ribs and deformities was seen.

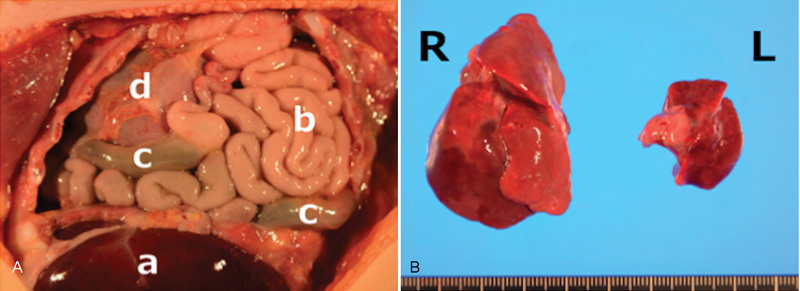

The autopsy findings included Bochdalek hernia-type CDH and severe pulmonary hypoplasia. The size of the defect in the diaphragm was 22 × 15 mm (type B). 5 His intestinal tract (from the duodenum to ascending colon) and spleen invaded the thoracic cavity ( Fig. 3A ). The right lung wet weight was 11.4 g (expected right lung wet weight adjusted by body weight derived from the autopsy database of Japanese sudden infant death syndrome diagnosed pathologically: 37.9 g) and the left lung wet weight was 3.2 g (expected left lung wet weight: 27.9 g). Both lungs showed normal lobulation ( Fig. 3B ). The right kidney was 20.3 g (expected right kidney weight: 17.9 g) and agenesis of the left kidney was present. We obtained parental consent to use the patient's data in our report.

Fig. 3.

Autopsy findings. ( A ) The neonate had left congenital diaphragmatic hernia without herniation of the liver (a) into the thoracic space. The intestine (b), colon (c), and spleen invaded the thoracic cavity. The heart (d) had shifted to the right side of the chest cavity. ( B ) The right lung (R) wet weight was 11.4 g and the left lung (L) wet weight was 3.2 g. Both lungs had normal lobulation.

Discussion

We presented a very rare case of fatal pulmonary hypoplasia with CDH, MMC, and thoracic dysplasia and discussed the mechanisms leading to fatal lung hypoplasia in this infant.

Currently, there are several systems for scoring the severity and predicting the prognosis of patients with isolated CDH. For example, Kitano's classification divides patients with isolated CDH into three groups according to liver and stomach position. 7 Based on this classification, CDH without herniation of the liver and stomach into the thoracic cavity has the most favorable prognosis (survival rate: 87%). Importantly, this classification is designed for isolated CDH and if applied to nonisolated CDH such as the present case, it would assess the prognosis as good. Another classification is that of Morini et al 5 based on the defect size in the diaphragm muscles. Under this system, our case would have been classified as type B, that is, a case in which the size of the defect is less than half the size of the left diaphragm. Although the prognosis of type B is usually not very poor, the outcome of our case was otherwise.

Because the CDH went unnoticed in our patient, we did not have data on his pulmonary hypoplasia in the prenatal diagnosis. We, therefore, calculated the score using data from his postmortem CT scans. The observed/expected lung area to head circumference ratio (o/e LHR) was 24% (<25% for severe cases), although this might have been underestimated due to his severe hydrocephalus. After adjusting the patient's head circumference by reference to the normal head circumference for gestational age (32.6 cm), we arrived at an adjusted o/e LHR of 31% (normal >45%).

In the present case, we hypothesized that two mechanisms were associated with the fatal and severe pulmonary hypoplasia. First, the herniation of the abdominal organs (the digestive tract and spleen) into the thoracic space would have inhibited lung growth by occupying the thoracic space as usually occurs in CDH. Second, the thoracic dysplasia due to scoliosis to the left side and the deformities of the vertebrae and ribs disrupted the growth of the thoracic cavity and lungs during the fetal period. As a result, both sides of the thoracic cavity were small, with the herniated intestine compressing the left lung and causing the displaced heart in turn to compress the right lung. This situation severely inhibited lung growth. Furthermore, the fetal breathing movements may have been suppressed by thoracic MMC, Chiari malformation type II, and severe hydrocephalus, although neither a recording of fetal breathing nor the bishop score was available for this case. Hydrocephalus and Chiari malformation type II may impair the function of the respiratory center or cranial nerves, which regulate the respiratory pattern and the laryngeal muscles, respectively. 8 Additionally, a peripheral nerve injury due to thoracic MMC in our patient could have impaired the function of accessory respiratory muscles. These mechanisms could then have decreased the fetal breathing movement and the capacity to maintain lung water, further inhibiting normal lung development.

Several reports have discussed the prognosis of infants with a combination of these anomalies.

The prevalence of the combination of CDH and MMC was reportedly 4.3% among 116 CDH cases. 3 While there are only a few reports of infants with CDH complicated with thoracic MMC and thoracic deformities who experienced fatal respiratory failure with severe pulmonary hypoplasia, the findings suggest that the combination of these three anomalies increases the severity of respiratory failure. 9 Recently, a case report on right-sided CDH with MMC was published. 10

Of the various types of MMC, thoracic MMC has the highest mortality rate. 11 Although the predominant cause of death was infection, in 37% of patients the cause of death was uncertain. On the other hand, the prevalence of scoliosis is reportedly 53% in MMC patients; however, the number of severe cases has not been reported. 12

Severe spondylothoracic dysostosis, a form of thoracic dysplasia, is reportedly a frequent cause of pulmonary dysplasia in itself. Of 27 patients with severe spondylothoracic dysostosis, 44% suffered from respiratory insufficiency and died within 6 months.

There are several limitations to this study. First, because the neonate had multiple abnormalities, there was a possibility that the severe pulmonary hypoplasia and severe PPHN were originally caused by genetic anomalies. Second, there is no definition of thoracic hypoplasia. Therefore, we were unable to predict the extent to which the thoracic dysplasia due to scoliosis and the deformities of the vertebrae and ribs may have influenced lung growth and development. Finally, there were no data indicating decreased fetal breathing movements or the capacity to maintain lung water. Our decision to perform late preterm elective delivery on account of the severe hydrocephalus may also have increased the risk of respiratory distress in this case.

In conclusion, we experienced a case of fatal pulmonary hypoplasia with CDH, thoracic MMC, and thoracic dysplasia. The combination of several congenital anomalies may have had a negative impact on fetal lung growth, leading to severe pulmonary hypoplasia. Therefore, when assessing the prognosis of neonates with CDH, we should take into account the adverse effects of complicated anomalies on lung development.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Messrs. Julian Tang and James R. Valera of the National Center for Child Health and Development for editing and proofreading this article. The editors are not responsible for any final changes made by the authors to the manuscript before submission.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

References

- 1.Nagata K, Usui N, Kanamori Y et al. The current profile and outcome of congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a nationwide survey in Japan. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(04):738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi S, Sago H, Kanamori Y et al. Prognostic factors of congenital diaphragmatic hernia accompanied by cardiovascular malformation. Pediatr Int. 2013;55(04):492–497. doi: 10.1111/ped.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sweed Y, Puri P.Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: influence of associated malformations on survival Arch Dis Child 199369(1 Spec No):68–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding R, Albuquerque C. Oxford: American Physiology Society; 1999. Pulmonary hypoplasia: role of mechanical factors in prenatal lung growth; pp. 364–394. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morini F, Valfrè L, Capolupo I, Lally K P, Lally P A, Bagolan P; Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group.Congenital diaphragmatic hernia: defect size correlates with developmental defect J Pediatr Surg 201348061177–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi S, Oishi Y, Ito N et al. Evaluating mortality and disease severity in congenital diaphragmatic hernia using the McGoon and pulmonary artery indices. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(11):2101–2106. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitano Y, Okuyama H, Saito M et al. Re-evaluation of stomach position as a simple prognostic factor in fetal left congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a multicenter survey in Japan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37(03):277–282. doi: 10.1002/uog.8892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura Y, Harada K, Yamamoto I et al. Human pulmonary hypoplasia. Statistical, morphological, morphometric, and biochemical study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992;116(06):635–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cetinkaya M, Ozkan H, Köksal N, Yazici Z, Yalçinkaya U. Spondylocostal dysostosis associated with diaphragmatic hernia and neural tube defects. Clin Dysmorphol. 2008;17:151–154. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e3282f2699c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali S R, Ahmed S. Right-sided congenital diaphragmatic hernia and myelomeningocele: a rare association. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2016;26(12):995–996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgstedt-Bakke J H, Fenger-Grøn M, Rasmussen M M. Correlation of mortality with lesion level in patients with myelomeningocele: a population-based study. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017;19(02):227–231. doi: 10.3171/2016.8.PEDS1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishit M, Michael D, Michael M, Robert N, Jhon W, Christopher B. Scoliosis in myelomeningocele: epidemiology, management, and functional outcome. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017;20:1–10. doi: 10.3171/2017.2.PEDS16641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]