Abstract

Objective

To examine the effectiveness of the three primary treatments for ureteropelvic junction obstruction (i.e., open pyeloplasty, minimally invasive pyeloplasty, and endopyelotomy) as assessed by failure rates.

Materials and Methods

Using MarketScan® data, we identified adults (ages 18–64) who underwent treatment for ureteropelvic junction obstruction between 2002 and 2010. Our primary outcome was failure (i.e., need for a secondary procedure). We fit a Cox proportional hazards model to examine the effects of different patient, regional, and provider characteristics on treatment failure. We then implemented a survival analysis framework to examine the failure-free probability for each treatment.

Results

We identified 1125 minimally invasive pyeloplasties, 775 open pyeloplasties, and 1315 endopyelotomies with failure rates of 7%, 9%, and 15%, respectively. Compared with endopyelotomy, minimally invasive pyeloplasty was associated with a lower risk of treatment failure (adjusted hazards ratio [aHR] 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39–0.69). Minimally invasive and open pyeloplasties had similar failure rates. Compared with open pyeloplasty, endopyelotomy was associated with a higher risk of treatment failure (aHR 1.78; 95% CI, 1.33–2.37). The average length of stay was 2.7 days for minimally invasive pyeloplasty and 4.2 days for open pyeloplasty (p<0.001).

Conclusions

Endopyelotomy has the highest failure rates, yet remains a common treatment for ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Future research should examine to what extent patients and physicians are driving the use of endopyelotomy.

Keywords: comparative effectiveness, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, minimally invasive pyeloplasty, open pyeloplasty, endopyelotomy

INTRODUCTION

Ureteropelvic junction obstruction is a common urologic condition with three primary treatments: open pyeloplasty, minimally invasive pyeloplasty, and endopyelotomy. While open pyleoplasty is the traditional approach, minimally invasive pyeloplasty (which includes both robotic-assisted and laparoscopic pyeloplasty) and endopyelotomy represent less-invasive options. All three treatments provide relatively high success rates and low morbidity.1–3

However, the evidence regarding the comparative effectiveness of these three treatments is limited. Although meta-analyses4 and large, multi-institutional studies5 have demonstrated similar efficacy between robotic-assisted and laparoscopic pyeloplasty, comparisons between these minimally invasive approaches and open pyeloplasty for adults are primarily limited to single-institution reviews with small numbers of patients.3,6–10 Moreover, outcomes used to measure success are often subjective (e.g., based on symptoms obtained from medical records).5 Regarding endopyelotomy, evidence supporting its use as a primary treatment is mixed. Some reports advocate endopyelotomy as a first-line treatment for adults with ureteropelvic junction obstruction due to success rates that approach that of open pyeloplasty,11,12 while others insist that it is an inferior treatment.13–16 Few studies have examined all three treatments on a population level.

For these reasons, we sought to examine the effectiveness of open pyeloplasty, minimally invasive pyeloplasty, and endopyelotomy for ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Understanding the relative effectiveness of these treatments is imperative for providing the best care for patients. Further, examining the comparative effectiveness of robotic and traditional approaches is a top priority by the Institute of Medicine.17

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

Using the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, we identified adults 18 to 64 years old who underwent treatment for ureteropelvic junction obstruction between 2002 and 2010. The MarketScan® database includes data for approximately 40 million employees and their dependents.18 We assigned patients to one of three treatments: minimally invasive pyeloplasty (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] code 50544), open pyeloplasty (HCPCS codes 50400, 50405), and endopyelotomy (HCPCS codes 50575, 52342, 52345, 52346). We only included patients who were continuously enrolled in a benefits plan for a minimum of 6 months prior to the treatment date. In addition, patients had to be continuously enrolled for at least 6 months after treatment. We excluded patients without documented follow-up imaging and excluded secondary procedures for ureteropelvic junction obstruction from our analyses. Using these criteria, our study population consisted of 1125 minimally invasive pyeloplasties, 775 open pyeloplasties, and 1315 endopyelotomies.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was failure after treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Failure was defined as the need for a secondary procedure (i.e., endopyelotomy, treatment of ureteral stricture, nephrectomy, pyeloplasty, ureteroplasty, or kidney transplant). We did not include reinsertion of a ureteral stent as a failure. We examined failure rates in patients with a minimum of 6, 12, and 24 months of follow up after treatment. Differences in failure rates among the three procedures were similar over these intervals, so we ultimately reported failures in patients with a minimum of 6 months of follow up to increase the precision of our estimates. We examined several patient (age, gender, comorbidity, benefit plan type, employment classification, employment status, treatment year), regional (metropolitan statistical area [MSA], region of residence), and provider (provider MSA) characteristics. Patient race/ethnicity is not provided in the dataset. We calculated comorbidity using inpatient and outpatient claims for the 6-month period prior to treatment.19

Statistical Analysis

First, we compared demographics across treatment types using chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. Then, we fit a Cox proportional hazards model to examine the effects of different patient, regional, and provider characteristics on treatment failure. We then implemented a survival analysis framework to examine the failure-free probability for each treatment. These models were adjusted for patient age, gender, comorbidity, benefit plan type, employment classification, employment status, region of residence, patient MSA, provider MSA, and treatment year. For the patients receiving an endopyelotomy, we performed a sensitivity analysis in which we excluded those who had a concomitant stone procedure and found failure rates to be similar. Lastly, we compared the hospital length of stay between the two inpatient procedures (minimally invasive and open pyeloplasty) using ANCOVA. All analyses were performed using SAS v9.3 (Cary, NC). All tests were two-sided, and the probability of a type I error was set at 0.05. The Institutional Review Board of the RAND cooperation determined that the study design was exempt from review.

RESULTS

The characteristics of patients undergoing minimally invasive pyeloplasty, open pyeloplasty, and endopyelotomy are demonstrated in Table 1. Overall, patients were young: mean age of 41, 43, and 49 years for minimally invasive pyeloplasty, open pyeloplasty, and endopyelotomy, respectively. The three treatments differed by benefit plan type (p=0.03), employment classification (p<0.001), employment status (p=0.01), MSA status (p<0.001), region of residence (p<0.001), failure rates (p<0.001), and year of treatment (p<0.001). Failure rates were 7%, 9%, and 15% for minimally invasive pyeloplasty, open pyeloplasty, and endopyelotomy, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient demographics according to treatment

| Characteristics | Minimally-invasive pyeloplasty (n=1125) | Open pyeloplasty (n=775) | Endopyelotomy (n=1315) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 41 (15) | 43 (15) | 49 (13) | <0.001 |

| Gender (%) | 0.69 | |||

| Male | 459 (41) | 319 (41) | 519 (39) | |

| Female | 666 (59) | 456 (59) | 796 (61) | |

| Comorbidity (%) | 0.39 | |||

| 0 | 975 (87) | 662 (85) | 1114 (85) | |

| 1 or more | 150 (13) | 113 (15) | 201 (15) | |

| Benefit plan type (%) | 0.03 | |||

| HMO | 130 (12) | 101(13) | 161 (12) | |

| PPO | 769 (68) | 480 (62) | 843 (64) | |

| Other | 226 (20) | 194 (25) | 311 (24) | |

| Employment classification (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Non-salaried | 251 (22) | 212 (27) | 372 (28) | |

| Salaried | 248 (22) | 131 (17) | 180 (14) | |

| Unknown | 626 (56) | 432 (56) | 763 (58) | |

| Employment status (%) | 0.01 | |||

| Non-full time | 664 (59) | 466 (60) | 850 (65) | |

| Full time | 461 (41) | 309 (40) | 465 (35) | |

| MSA status (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Non-MSA | 157 (14) | 147 (19) | 283 (22) | |

| MSA | 968 (86) | 628 (81) | 1032 (78) | |

| Region of residence (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Northeast | 157 (14) | 86 (11) | 146 (11) | |

| North Central | 343 (30) | 211 (27) | 268 (20) | |

| South | 466 (41) | 345 (45) | 669 (51) | |

| West | 147 (13) | 123 (16) | 215 (16) | |

| Unknown | 12 (1) | 10 (1) | 17 (1) | |

| Failure (%) | 82 (7) | 69 (9) | 196 (15) | <0.001 |

| Year of treatment (%) | <0.001 | |||

| 2002** | 5 (<1) | 36 (5) | 37 (3) | |

| 2003 | 27 (2) | 85 (11) | 81 (6) | |

| 2004 | 54 (5) | 86 (11) | 128 (10) | |

| 2005 | 90 (8) | 92 (12) | 134 (10) | |

| 2006 | 115 (10) | 89 (11) | 162 (12) | |

| 2007 | 157 (14) | 97 (13) | 199 (15) | |

| 2008 | 240 (21) | 116 (15) | 222 (17) | |

| 2009 | 255 (23) | 109 (14) | 200 (15) | |

| 2010 | 182 (16) | 65 (8) | 152 (12) |

Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; MSA, metropolitan statistical area; PPO, preferred provider organization; SD, standard deviation

P-values generated from chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA tests for continuous variables.

Other includes comprehensive, exclusive provider organization, point of service, point of service with capitation, consumer directed health plan, and missing

The number of patients in 2002 is lower across treatment types due to the need to have 6 months of data available prior to the treatment date in order to calculate patient comorbidity.

Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

The results of the Cox proportional hazards models are shown in Table 2. Compared with endopyelotomy, minimally invasive pyeloplasty was associated with a lower risk of treatment failure (adjusted hazards ratio [aHR] 0.52; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.39–0.69). In comparing these two treatments, minimally invasive pyeloplasty was also associated with a higher likelihood of failure if performed in the south (aHR 1.73; 95% CI, 1.11–2.70) and west (aHR 1.70; 95% CI, 1.02–2.81) as opposed to the northeast. For the comparison of minimally invasive and open pyeloplasty, failure rates were similar across all measured covariates except for treatment year: compared with open pyeloplasty, minimally invasive pyeloplasty was associated with a lower risk of failure with subsequent years (aHR 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83–0.97). Compared with open pyeloplasty, endopyelotomy was associated with a higher risk of treatment failure (aHR 1.78; 95% CI, 1.33–2.37) and was associated with a higher likelihood of failure if performed on patients with 1 or more comorbidities (aHR 1.37; 95% CI, 1.01–1.86).

Table 2.

Estimated effect (adjusted hazards ratio* and 95% confidence interval) of each predictor on treatment failure: Results of Cox proportional hazards models.

| Characteristic | Minimally invasive pyeloplasty vs. endopyelotomy | Minimally invasive pyeloplasty vs. open pyeloplasty | Endopyelotomy vs. open pyeloplasty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment type | |||

| Minimally invasive pyeloplasty | 0.52 (0.39–0.69) | 0.98 (0.68–1.42) | -- |

| Open pyeloplasty | -- | 1 | 1 |

| Endopyelotomy | 1 | -- | 1.78 (1.33–2.37) |

| Age | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.99 (0.99–1.01) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Male | 1.13 (0.89–1.44) | 1.23 (0.87–1.74) | 0.99 (0.78–1.26) |

| Comorbidity | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 or more | 1.30 (0.97–1.80) | 1.35 (0.85–2.15) | 1.37 (1.01–1.86) |

| Benefit plan type | |||

| HMO | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PPO | 1.05 (0.74–1.50) | 1.20 (0.69–2.09) | 1.17 (0.81–1.70) |

| Other** | 1.15 (0.76–1.74) | 1.13 (0.59–2.16) | 1.17 (0.76–1.79) |

| Employment classification | |||

| Non-salaried | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Salaried | 0.97 (0.67–1.40) | 1.21 (0.72–2.05) | 0.85 (0.58–1.26) |

| Unknown | 0.92 (0.67–1.27) | 1.40 (0.85–2.32) | 0.94 (0.68–1.30) |

| Employment status | |||

| Non-full time | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Full time | 0.81 (0.60–1.09) | 1.14 (0.74–1.75) | 0.92 (0.68–1.23) |

| Region of residence | |||

| Northeast | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| North Central | 1.26 (0.77–2.06) | 1.24 (0.66–2.34) | 0.83 (0.52–1.32) |

| South | 1.73 (1.11–2.70) | 1.38 (0.75–2.54) | 1.15 (0.77–1.71) |

| West | 1.70 (1.02–2.81) | 1.58 (0.79–3.15) | 1.04 (0.65–1.67) |

| Unknown | 2.07 (0.71–6.04) | 0 (0–>100) | 1.33 (0.46–3.79) |

| Patient MSA | 1.22 (0.87–1.70) | 1.25 (0.75–2.09) | 1.36 (0.96–1.92) |

| Provider MSA | 0.80 (0.53–1.20) | 1.23 (0.59–2.56) | 0.92 (0.60–1.40) |

| Treatment year | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 0.90 (0.83–0.97) | 0.97 (0.92–1.03) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HMO, health maintenance organization; MSA, metropolitan statistical area; PPO, preferred provider organization

The effect of each predictor was adjusted for all other predictors in the model

Other includes comprehensive, exclusive provider organization, point of service, point of service with capitation, consumer directed health plan, and missing

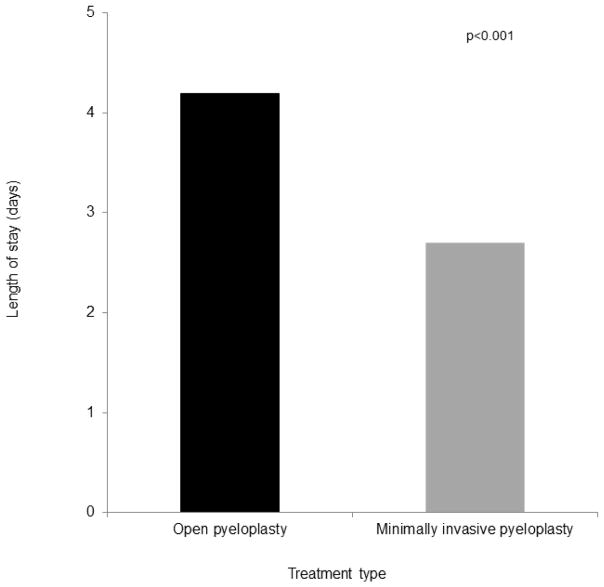

Overall, the adjusted failure-free probabilities were high for all three treatments (Figure 1). Endopyelotomy had the lowest failure-free rates (logrank p<0.0001). For all three treatments, the majority of failures occurred within the first two years.

Figure 1.

Adjusted* failure-free probability, according to treatment type

* Adjusted for age, gender, comorbidity, benefit plan type, employment classification, employment status, region of residence, patient MSA, provider MSA, and treatment year.

Overall, the adjusted failure-free probabilities were high for all three treatments. Endopyelotomy had the lowest failure-free rates (logrank p<0.0001). For all three treatments, the majority of failures occurred within the first two years.

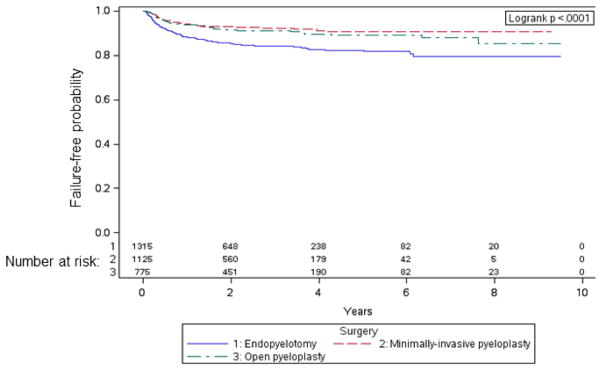

Among the two inpatient procedures (minimally invasive and open pyeloplasty), hospital length of stay was shorter for minimally invasive pyeloplasty (Figure 2). The average length of stay was 2.7 days for minimally invasive pyeloplasty and 4.2 days for open pyeloplasty (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Adjusted* hospital length of stay after minimally invasive and open pyeloplasty

*Adjusted for age, gender, comorbidity, benefit plan type, employment classification, employment status, region of residence, patient MSA, provider MSA, and treatment year.

The hospital length of stay was significantly shorter for minimally invasive pyeloplasty compared to open pyeloplasty (p<0.001, ANCOVA).

DISCUSSION

Overall, the failure rates for minimally invasive pyeloplasty, open pyeloplasty, and endopyelotomy were 7%, 9%, and 15%, respectively. Most failures occurred within the first two years of follow up. Endopyelotomy had the highest failure rates; no differences in failure rates were observed between minimally invasive and open pyeloplasty. Among the two inpatient procedures, minimally invasive pyeloplasty had a shorter hospital length of stay.

Of the three treatments, endopyelotomy had the highest failure rates and remained a commonly performed procedure. Conceptually, the higher failure rate makes sense since pyeloplasties involve dismembering the abnormal ureteral tissue and creating a more patent connection whereas endopyelotomies involve an incomplete incision without any dismembering. What is concerning is that despite a failure rate that is 1.5 to 2-fold higher than for pyeloplasty, endopyelotomy remains a common treatment for ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Although endopyelotomy is a good treatment for pyeloplasty failures,20 this does not explain the high number of endopyelotomies in this study since we excluded secondary procedures from our cohort: the 1315 endopyelotomies all represent primary treatments.

There are a few possible explanations for the high rate of endopyelotomies. First, some of these procedures included concomitant stone surgery, which may make an endopyelotomy the preferred approach in many of these instances. Second, it is a less invasive procedure that involves less post-operative pain, requires less operating time, and is routinely done as an outpatient.3 As such, despite its higher failure rate, it is an attractive treatment for patients who are older and sicker. However, our findings do not support this explanation. Although endopyelotomy patients are significantly older, they are only 49 years old, on average. Further, there are no differences among the three treatments in terms of the number of patient comorbidities. A more likely explanation is that many providers prefer to perform an endopyelotomy as a primary treatment because it is technically easier. Pyeloplasties involve skin incisions, dismembering the ureter, and suturing whereas endopyelotomies essentially avoid these issues. When laparoscopic pyeloplasties emerged, providers were enthusiastic about improved cosmesis,9 quicker convalescence,21 and decreased post-operative pain,21,22 but suturing was technically difficult.13 More recently, robotic-assisted pyeloplasties have made suturing easier.1 Experience with robotic surgery is now commonplace in residency training,23,24 and indeed, the number of minimally invasive pyeloplasties increased over the study period, surpassing endopyelotomy as the most common treatment in the last three years of the study.

Minimally invasive pyeloplasties had similar failure rates as open pyeloplasties, yet were associated with shorter hospital length of stays. From a technical standpoint, the similar failure rates are not surprising since the principles of the operation are the same. Likewise, the shorter hospital length of stay associated with the minimally invasive pyeloplasty makes sense given that this less-invasive approach typically involves smaller incisions9 and less pain.21,22 On average, patients who received a minimally invasive pyeloplasty were discharged 1.5 days earlier, which represented a 36% reduction in the duration of their admission.

As our health care system strives to provide the highest value care, these findings have several implications. First, endopyelotomy remained a common treatment for ueteropelvic junction obstruction despite fairly similar patient characteristics and higher failure rates. Especially with the increasing use of minimally invasive pyeloplasty and its associated decreased hospital length of stay compared with open pyeloplasty, the argument that endopyelotomy is less invasive is less intriguing. Insofar as physicians offer endopyelotomy as the primary treatment because they are uncomfortable performing pyeloplasties, there should be a greater emphasis on referring these patients to specialists. Second, compared with endopyelotomy, there is a higher likelihood of failure with minimally invasive pyeloplasty in the south and west regions compared with the northeast. The association of better outcomes with higher volume is well described in the surgical literature25,26 and, although the absolute numbers of both minimally invasive pyeloplasties and endopyelotomies are high in these regions, provider volume should be examined to see if this helps explain the higher failure rates in these regions. If patients do better when their pyeloplasties are performed by high-volume providers, then this again raises the question as to whether these patients should be referred to providers who specialize in this procedure.

Third, the similar failure rates and shorter hospital length of stay with minimally invasive pyeloplasty compared with open pyeloplasty suggest that this should be the preferred pyeloplasty approach assuming that it is not contraindicated (e.g., significant adhesions from prior surgeries). Since the hospital length of stay was 36% shorter, this could result in significant cost savings to both patients and our health care system.

In interpreting our findings, it is important to consider several limitations. We are using administrative claims data to identify treatment failures, which is imperfect. We cannot account for certain factors that may be associated with failure, such as case complexity, the presence of crossing vessels, and body habitus. We also cannot measure all aspects of failure, for example patient symptoms, renal function, or concerns on radiographic imaging. Lastly, we are indirectly assigning failure based on secondary procedures. However, we have taken two steps to help strengthen our measurement of failure. First, we only included procedures that would most clearly represent a failure (e.g., a pyeloplasty after an endopyelotomy) and did not include procedures less likely to indicate a true failure (e.g., reinsertion of a stent). Second, we excluded all patients without follow-up imaging so that patients lost to follow up were not inadvertently labeled as a success.

Another limitation is the potential lack of generalizability of our findings. The MarketScan® database collects information on working age adults, their spouses, and dependents. Thus, our findings may not be generalizable to other individuals, such as those who are uninsured or the elderly. However, MarketScan® represents a geographically diverse population of millions of working-age adults and their families, which represents the most likely population to receive treatment for uteropelvic junction obstruction.27

In summary, there are two reasons this study merits consideration. First, endopyelotomy has the highest failure rates, yet remains a common treatment for ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Future research should examine to what extent patients and physicians are driving the use of endopyelotomy and should examine how provider volume affects failure rates for these three treatments. Second, given the similar failure rates and shorter hospital length of stay associated with minimally invasive pyeloplasty, this approach may supplant open pyeloplasty as the “gold standard” in the near future.

Acknowledgments

Bruce Jacobs is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Institutional KL2 award (KL2TR001856), the GEMSSTAR award (R03AG048091), the Jahnigen career development award, and the Tippins Foundation Scholar Award.

Brent Hollenbeck is supported in part by the National Institutes on Aging (R01 AG04871).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hopf HL, Bahler CD, Sundaram CP. Long-term Outcomes of Robot-assisted Laparoscopic Pyeloplasty for Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction. Urology. 2016;90:106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gogus C, Karamursel T, Tokatli Z, et al. Long-term results of Anderson-Hynes pyeloplasty in 180 adults in the era of endourologic procedures. Urol Int. 2004;73:11–14. doi: 10.1159/000078796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooks JD, Kavoussi LR, Preminger GM, et al. Comparison of open and endourologic approaches to the obstructed ureteropelvic junction. Urology. 1995;46:791–795. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80345-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braga LH, Pace K, DeMaria J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of robotic-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic pyeloplasty for patients with ureteropelvic junction obstruction: effect on operative time, length of hospital stay, postoperative complications, and success rate. Eur Urol. 2009;56:848–857. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucas SM, Sundaram CP, Wolf JS, Jr, et al. Factors that impact the outcome of minimally invasive pyeloplasty: results of the Multi-institutional Laparoscopic and Robotic Pyeloplasty Collaborative Group. J Urol. 2012;187:522–527. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siqueira TM, Jr, Nadu A, Kuo RL, et al. Laparoscopic treatment for ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Urology. 2002;60:973–978. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh I, Hemal AK. Robot-assisted pyeloplasty: review of the current literature, technique and outcome. Can J Urol. 2010;17:5099–5108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soulie M, Thoulouzan M, Seguin P, et al. Retroperitoneal laparoscopic versus open pyeloplasty with a minimal incision: comparison of two surgical approaches. Urology. 2001;57:443–447. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)01065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klingler HC, Remzi M, Janetschek G, et al. Comparison of open versus laparoscopic pyeloplasty techniques in treatment of uretero-pelvic junction obstruction. Eur Urol. 2003;44:340–345. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon DA, El-Shazly MA, Chang CM, et al. Laparoscopic pyeloplasty: evolution of a new gold standard. Urology. 2006;67:932–936. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kletscher BA, Segura JW, LeRoy AJ, et al. Percutaneous antegrade endopyelotomy: review of 50 consecutive cases. J Urol. 1995;153:701–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shalhav AL, Giusti G, Elbahnasy AM, et al. Adult endopyelotomy: impact of etiology and antegrade versus retrograde approach on outcome. J Urol. 1998;160:685–689. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)62755-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yanke BV, Lallas CD, Pagnani C, et al. The minimally invasive treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction: a review of our experience during the last decade. J Urol. 2008;180:1397–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rassweiler JJ, Subotic S, Feist-Schwenk M, et al. Minimally invasive treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction: long-term experience with an algorithm for laser endopyelotomy and laparoscopic retroperitoneal pyeloplasty. J Urol. 2007;177:1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldwin DD, Dunbar JA, Wells N, et al. Single-center comparison of laparoscopic pyeloplasty, Acucise endopyelotomy, and open pyeloplasty. J Endourol. 2003;17:155–160. doi: 10.1089/089277903321618716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dimarco DS, Gettman MT, McGee SM, et al. Long-term success of antegrade endopyelotomy compared with pyeloplasty at a single institution. J Endourol. 2006;20:707–712. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.100 Initial Priority Topics for Comparative Effectiveness Research. Institute of Medicine; 2009. [Accessed July 29, 2016]. Available from: http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/~/media/Files/Report%20Files/2009/ComparativeEffectivenessResearchPriorities/Stand%20Alone%20List%20of%20100%20CER%20Priorities%20-%20for%20web.ashx. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen LG, Chang S. [Accessed June 11, 2015];Health research data for the real world: The MarketScan databases. Available from: http://truvenhealth.com/portals/0/assets/PH_11238_0612_TEMP_MarketScan_WP_FINAL.pdf.

- 19.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan HJ, Ye Z, Roberts WW, et al. Failure after laparoscopic pyeloplasty: prevention and management. J Endourol. 2011;25:1457–1462. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bansal P, Gupta A, Mongha R, et al. Laparoscopic versus open pyeloplasty: Comparison of two surgical approaches- a single centre experience of three years. J Minim Access Surg. 2008;4:76–79. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.43091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 22.Bonnard A, Fouquet V, Carricaburu E, et al. Retroperitoneal laparoscopic versus open pyeloplasty in children. J Urol. 2005;173:1710–1713. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154169.74458.32. discussion 1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liberman D, Trinh QD, Jeldres C, et al. Training and outcome monitoring in robotic urologic surgery. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9:17–22. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duchene DA, Moinzadeh A, Gill IS, et al. Survey of residency training in laparoscopic and robotic surgery. J Urol. 2006;176:2158–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.035. discussion 2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Begg CB, Riedel ER, Bach PB, et al. Variations in morbidity after radical prostatectomy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1138–1144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa011788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sukumar S, Sun M, Karakiewicz PI, et al. National trends and disparities in the use of minimally invasive adult pyeloplasty. J Urol. 2012;188:913–918. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]