Abstract

Background

Dentists strive to provide safe and effective oral healthcare. However, some patients may encounter an adverse event (AE) defined as “unnecessary harm due to dental treatment”. In this research we propose and evaluate two systems for categorizing the type and severity of AEs encountered at the dental office.

Methods

Several existing medical AE type and severity classification systems were reviewed and adapted for dentistry. Using data collected in prior work, two initial dental AE type and severity classification systems were developed. Eight independent reviewers performed focused chart reviews and AEs identified were used to evaluate and modify these newly developed classifications.

Results

958 charts were independently reviewed. Among the reviewed charts, 118 prospective AE’s were found and 101 (85.6%) were verified as AEs through a consensus process. At the end of the study, a final AE Type classification comprising 12 categories, and an AE severity classification comprising 7 categories emerged. Pain and infection were the most common AE types representing 75% of the cases reviewed (55% and 17% respectively) and 88% were found to cause temporary, moderate to severe harm to the patient.

Conclusions

AEs found during the chart review process were successfully classified using the novel dental AE type and severity classifications. Understanding the type of AEs and their severity are important steps if we are to learn from and prevent patient harm in the dental office.

Keywords: Adverse Event, Dentistry, Classification, Severity, Harm, Quality, Learning Organization

INTRODUCTION

Dentists, as doctors of oral health, oversee clinical teams to ensure the delivery of “safe and effective oral care”.1 Emerging scientific literature2–11 however, suggest that dental patients experience a significant number of adverse events (AEs) or unnecessary harm while receiving dental care, such as, tooth crown ingestion or aspiration, wrong tooth extraction, or unexpected severe and prolonged pain after molar extractions. Providing safe oral care implies reducing the risk of inflicting unnecessary harm to the dental patient to an acceptable minimum.7 Harm refers to any “impairment of structure or function of the body and/or any deleterious effect arising there from”.12 The patient safety paradigm13 starts with the proper identification and assessment of AEs in a professional culture open to learning from mistakes.14 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed a detailed patient safety initiative with a goal to “have a positive impact on patient safety by providing knowledge and tools to understand medical errors and to create solutions that mitigate or eliminate harm to patients suffered as a result of health care.”13 To the best of our knowledge, specific dental-related patient safety metrics are yet to be developed. In order to fill this gap, the authors obtained grant funding (NIDCR 1R01DE022628-01A1) to develop a patient safety initiative for dentistry.

In addition, other healthcare industries such as the pharmaceutical and medical device research industries have mandatory reporting requirements for clinical research. When AEs occur, they systematically document the seriousness of the AE (level of harm), its impact on enrolled participants, and its association with a study related device, drug, or procedure. This enables the identification of the various contributing factors and allows for the creation and dissemination of recommendations for systems changes.15 By contrast, clinical dentistry does not have any such mandatory reporting requirements for AEs, and if we did, there would be no standardized format for reporting these events. A dental AE classification system would help to better organize and communicate about the types of harm in the dental office. It would provide insights into their prevention, elimination and/or the mitigation of their effects. The impact of AEs is also not equal, some cause greater harm than others, therefore, a standardized severity rating is needed to understand the extent of damage caused by AEs. In the absence of any precursory dental-specific metrics and tools, we turned to systems developed by the medical profession for classifying, assessing severity and reporting AEs.

The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0 (CTCAE) is a comprehensive categorization system of AEs in cancer treatment that includes a severity grading scale for AEs.16 It uses terms taken from the clinically validated Medical Dictionary of Regulatory Activities (MedDRA’s), and is organized across 24 primary System Organ Classes.16 Another notable classification system was used in the Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS), which categorized hospital adverse events according to the type of injury and incorporated a six-point disability scale on which “serious” disability was defined as disability persisting for more than six months17. Adverse events were classified in operative and non-operative, each containing five and ten sub-categories respectively18. The World Health Organization (WHO’s) International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS) is a conceptual framework that consists of ten high-level classes, each further hierarchically subdivided into categories and sub-categories.12 Forty-eight concepts have been identified with agreed upon definitions and preferred terms.12 The degree of harm is defined along five levels from none to death.12, 19 The ICPS is not considered a classification, but rather a framework with a set of concepts that are linked by semantic relationships.12, 19

Similarly, the Medicare Hospital-Acquired Conditions classification20 contains ten categories that are mainly surgical and post-surgical management related, however, it does not have a severity rating scheme. The United States (US) National Quality Forum (NQF) captures the level of harm in serious reportable events (SREs).21 As part of the Outpatient Adverse Event Trigger Tool developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI)22, a severity classification methodology was proposed using the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) Index for Categorizing Errors.23 In sum, medical classification and severity rating systems demonstrate the viability of monitoring patient safety; important steps in moving towards a patient safety initiative.4 As expected, our evaluation of these systems quickly revealed that dental AEs do not neatly fit into the categories developed in the medical realm. Similarly, the level of severity of dental AEs did not easily fit within the existing medical severity scales. The focus of this paper is to report on the methodology for developing and refining a usable dental AE classification and severity rating system, and the results of a pilot study to evaluate its usefulness in classifying AEs found through chart reviews.

METHODS

The research was reviewed and approved by the Human Subject Committees of all participating academic institutions.

Development And Refinement Of The Dental AE Type Classification

The following five medical classifications were analyzed for their overlap in categories: (1) NCI’s CTCAE16 twenty-four System Organ Classes, (2) HMPS24 eleven categories, (3) WHO’s ICPS12, 19 thirteen categories within the “Incident Type” class (4) IHI outpatient trigger tool’s22 eleven categories, and (5) Medicare’s Hospital-Acquired Conditions’20 ten categories.

NCI’s CTCAE lists a total of 679 AEs, from which we identified 86 items that were potentially related to oral health (Appendix 1). We studied the HMPS classification scheme18, and its operative and non-operative categories that include the following sub-categories of AEs: Wound infection, Technical complication, Late complication, Non-technical complication, Surgical failure, Drug-related, Diagnostic mishap, Therapeutic mishap, Procedure-related, Fall, Fracture, Postpartum, Anesthesia-related, Neonatal, and System/other. A condensed version of the HMPS categorization was introduced by Nuckols et al24 with 10 broad categories:1. Medications, 2. Operations, 3. Therapeutics, 4. Diagnostics, 5. Miscellaneous, 6. Procedures, 7. Anesthesia, 8. Peripartum, 9. Neonatal, and 10. Falls. The WHO’s ICPS12, 19 also has ten high-level classes: the first class, “Incident Type,” contains thirteen major categories: Clinical Administration, Clinical Process/Procedure, Documentation, Healthcare Associated Infection, Medication/IV Fluids, Blood/Blood Products, Nutrition, Medical Device/Equipment, Behavior, Patient Accidents, Infrastructure/Building/Fixtures, and Resources/Organizational Management. The IHI’s outpatient trigger tool22 includes medically-oriented items that indicate an AE may have occurred. Items include new diagnosis of cancer; nursing home placement, admission and discharge from the hospital, two or more consults in one year, surgical procedure, emergency room visit, greater than five medications, physician change, complaint letter, greater than three nursing calls in one week, and abnormal lab value. The final medical AE classification system analyzed was Medicare Hospital-Acquired Conditions.20 It included foreign object retained after surgery, air embolism, blood incompatibility, pressure ulcers, falls, manifestations of poor glycemic control, catheter-associated urinary tract infection, vascular catheter-associated infection, deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism, and surgical site infection.

The initial dental AE type classification (comprising 23 categories) was developed by analyzing dental AEs reported to the FDA MAUDE database,2 and documented in the scientific literature.25 This work produced a dental AE list that was expanded after collecting a list of commonly encountered AEs from dental providers.26 The initial dental AE type classification and the aggregated findings from our comprehensive analysis of medical AE classification systems were reviewed by the research group’s Advisory Committee, comprising experts in medical AEs (see acknowledgments). The findings from each preceding stage of this process led to the creation of a working system for classifying dental AEs. This classification was then pilot tested by independent reviewers across the 4 sites using a focused chart review process. This led to the further refinement of the AE classification and Severity systems. For example, during the calibration process for the chart reviews, we discovered that sinus perforation (a frequently reported AE in our previous study26 could be classified as either a soft tissue injury, or a hard tissue injury. As a result, we created an additional classification for AEs that did not fit into a single existing category; Other Oro-facial Harm. We also dropped the use of the word “complication” and replaced it with “harm.” The last three of the twelve AE classification categories in table 1 are now “other oro-facial harm”, “other systemic harm,’ and “other harm.” Finally, all prospective AE cases were verified collectively using a consensus process during conferences calls and a full-day in-person working meeting.

Table 1.

Dental AE Type Classification

| AE Category | AE Count |

|---|---|

| Pain | 56 |

| Infection | 17 |

| Hard tissue damage | 12 |

| Nerve injury | 6 |

| Soft tissue damage/inflammation | 5 |

| Other oro-facial harm | 2 |

| Allergy, toxicity, or foreign body response | 1 |

| Aspiration or ingestion of foreign body | 1 |

| Wrong site, wrong patient, or wrong procedure | 0 |

| Bleeding | 0 |

| Other systemic harm | 1 |

| Other harm | 0 |

| Total | 101 |

Development And Refinement Of The Dental AE Severity Classification

To our knowledge, there is no standardized measure for assessing the severity of dental AEs. In order to develop a severity scale for the AE classifications, we systematically reviewed the severity ratings of AEs used in the IHI outpatient trigger tool, NCI CTCAE, WHO ICPS, and NQF.

The Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) outpatient trigger tool22 has five categories of harm. From least to most severe they are: Temporary harm to the patient and required intervention, Temporary harm to the patient and required initial or prolonged hospitalization, Permanent patient harm, Intervention required to sustain life, and Patient death. The CTCAE16 assesses the severity of an AE through five gradients of harm. From least to most severe they are graded: 1. Mild; asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated, 2. Moderate; minimal, local or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental ADLs (activities of daily living), 3. Severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self-care ADLs, 4. Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated, and 5. Death related to AE. The WHO ICPS used a five-point gradient for assessing the degree of harm: None, Mild, Moderate, Severe, and Death. Finally, we reviewed the NQF list of serious reportable events (SREs).21 SREs included: Surgical or invasive procedure events, Product or device events, Patient protection, Care management events, Environmental, Radiological events and Potential criminal events.

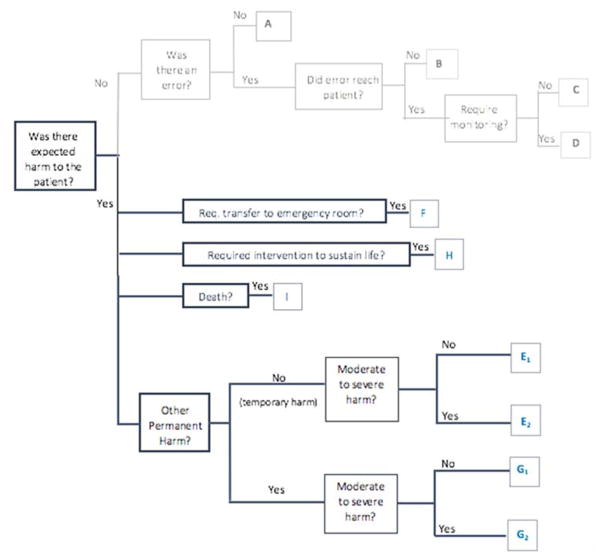

Using the findings from our review of the medical AE severity ratings, and feedback from our advisory committee, we created an initial AE severity rating scale which was used to assess the severity of AEs in our prior work25 and modified in subsequent work3. Based on our observations in these studies and through an iterative process, we further refined the severity scale and created a severity tree to simplify its use in the chart review process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dental AE Severity Tree

Description of Dental AE Severity Categories:

- Category E1: Temporary (reversible or transient) minimal/mild harm to the patient

- Category E2: Temporary (reversible or transient) moderate to severe harm to the patient

- Category F: Harm to the patient that required transfer to emergency room and/or prolonged hospitalization

- Category G1: Permanent minimal/mild patient harm

- Category G2: Permanent moderate to severe patient harm

- Category H: Intervention required to sustain life

- Category I: Patient death

Severity tree showing the chart review process for assigning severity categories to an adverse event. The reviewer begins on the left side and follows the branches of the tree to the right by answering each question.

Pilot Test (Chart Review Process)

Eight independent research team members representing four US academic dental institutions (two per site) performed focused chart reviews22 using eight newly constructed or previously developed triggers3 of active electronic health records (EHRs). A ‘trigger’ is an opportunity or clue used to identify AEs in a patient’s dental record but do not represent AEs themselves. The eight reviewers were tasked with determining whether the case fit the definition of an AE. The outcome of interest was AE type, which was measured as a binary variable based on the dental AE classification, as well as, the severity. A standardized log sheet was developed to extract the AEs from the charts. The reviewers were trained and calibrated using a uniform AE definition, classification (AE Type), and level of harm (AE Severity). Inter-rater reliability was calculated using the prevalence and bias-adjusted kappa to address the kappa paradox. The average percent agreement for AE determination was 82.2%. Further, the average, pairwise prevalence and bias adjusted kappa (PABAK) was 57.5% (κ=0.575) for determining AE presence. The average percent agreement for categorization of the AE type 78.5% while the PABAK was 48.8%. Lastly, the average percent agreement for categorization of AE severity was 82.2% and the corresponding PABAK was 71.7%. According to the standards for inter-rater reliability, a kappa ranging from 0.40 to 0.60 constitutes moderate agreement.27, 28 All statistical calculations were performed in R v3.1.1© using the “irr” and “epiR” packages.

RESULTS

Dental AE Type Classification

A comparison of the five medical AE classifications showed an overlap of concepts in the surgical/medical procedure, general disorders and infection categories (Appendix 2). Specifically, the CTCAE had more items that overlapped with the other classification systems than did any of the others. We also observed that similar concepts were presented with different wording across classifications. Although the CTCAE exemplified a comprehensive listing of potential AEs for cancer patients (n=679), only 87 of its items appeared to have potential relevance to oral health or dentistry. We concluded that using the system organ classes in the CTCAE was not effective for documenting oral health AEs. Similarly, the HMPS categories, Medicare’s Hospital-Acquired Conditions, and the ICPS also appear well suited to categorize medical and hospital AEs, but not oral health events. For example, categories to indicate damage to hard oral tissues, e.g. teeth were difficult to categorize using the existing schemes.

Suggestions that came from the medical AE experts on the Advisory committee were critical. Based on their early experiences developing medical classification systems, they suggested testing the clinical validity of any given AE with the “give me a break” test. That is, in order to label an event an AE, it must stand up to the rigor of peer review by professional colleagues. For example, would the failure of a provisional crown constitute an AE? Initially, we thought yes, but while it would be undesirable to have a provisional crown fail, a singular failure did not pass this test. On the other hand, if the provisional crown failed time and again, was aspirated or led to an abutment tooth fracture, it would be considered an AE. A similar example in medicine would be vomiting after chemotherapy, which the Advisory Committee explained was not considered an AE in itself, unless ongoing violent vomiting resulted in an inability to absorb nutrients and requiring parental nutrition/rehydration.

Putting together our findings from the analysis of these five medical AE classifications, the dental AEs found through the FDA MAUDE database2, our literature review,25 our empirical interviews with providers26, our consultation with the Advisory Committee on this project, and our focused chart reviews, we made revisions to the initial dental AE classification system26 and arrived at 12 final categories for the Dental AE Type Classification System.

Dental AE Severity Classification

In reviewing the four medical severity ratings, we found that while they effectively reflected increasing degrees of severity based upon the temporal impact of harm and what was needed to mitigate the effects of the AE, it was not fully applicable to outpatient dentistry. AEs in dentistry appear to be less catastrophic, and as such, we felt it necessary to be able to differentiate not only between temporary and permanent harm but indicate if the harm was mild or severe.

Specifically, we noted that the CTCAE severity grades, ICPS and the IHI scales had some similarities (death, intervention required). They also had relevance for oral health. The NQF SREs focused on causes rather than AEs. While the SREs may be of importance to root cause analysis for sentinel events, they did not fit for severity ratings for dental AEs. By contrast, the IHI scale had utility for dentistry. It assessed harm based upon the short and long term impact of the AE upon the patient. The more severe the immediate impact, or more extensive the long-term mitigation required, the higher the severity rating. We used this approach in developing our own severity scale for dental AEs.

Items from the IHI trigger tool, ICPS and the CTCAE were integrated into more granular elements specific to oral health. With the support of the Advisory Board, we developed an initial AE severity scale for oral health comprising 15 items. This scale was pilot tested in our prior work analyzing the scientific literature.25 Based on feedback from the reviewers, and through an iterative process, it was further condensed, simplified and adapted into a severity tree (Figure 1). The first four items on the scale (A–D) were dropped, the “magnitude of the intervention” was also dropped from each step, and the “moderate” and “severe” categories were combined. The final step was the application of the severity scale to AEs identified through EHR chart reviews by independent reviewers across several sites.

Overall Evaluation Of The Dental AE Type and Severity Classifications

The following shows an example of a case that a reviewer would be asked to classify:

“While a gold onlay for #30 was being tried in prior to cementation, the onlay inadvertently became dislodged and lost in the oropharyngeal space. KUB revealed a radiopaque foreign object in the area of the duodenum, measuring approximately 1cm. Patient informed that her airways were clear and that she will pass the foreign body.”

Reviewers would classify the above as adverse event type: “Aspiration/Ingestion of Foreign Body” with severity of Temporary (reversible or transient) moderate to severe harm to the patient (E2).

There were 3283 (not including random charts) triggered charts. Of these, 958 charts were independently reviewed representing 29% of the triggered population. Among the reviewed charts, 118 prospective AE’s were found and 101 (85.6%) were verified as AEs during the consensus process. Pain and infection were the most common AE types representing 75% of the cases reviewed (55% and 17% respectively). In the remaining reviews, hard tissue damage was assessed in 12%, soft tissue damage/inflammation in 6%, nerve injury in 5%, and other oro-facial harm in 2% of cases. Examples of AEs found during the chart reviews include: dry socket, failure of implant to osseo-integrate two months after placement with loss of bone and requiring removal; pulp exposure during caries removal due to sudden movement of pediatric child; pain; and excessive swelling. Results of the classification after consensus was reached are documented in Table 1. Overwhelmingly, the most recorded adverse event severity was “temporary, moderate to severe harm to the patient” (E2) representing 88% of the cases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Dental AE Severity Classification

| AE Severity | Count |

|---|---|

| E2 (Temporary Moderate to Severe Harm) | 89 |

| G2 (Permanent Moderate to Severe Harm) | 10 |

| E1 | 0 |

| G1 | 1 |

| Total | 101 |

DISCUSSION

The medical profession has made considerable strides understanding patient safety. It is now time for dentistry to embrace patient safety and move towards a better safety initiative.4, 29 In order to create, monitor and maintain what AHRQ describes as a patient safety initiative,13 the identification and assessment of AEs are important first steps. The AE classifications and severity ratings provide unique opportunities to the dental profession to explore how to provide safe and effective high quality oral care to patients. The nature of adverse events that have been reported in the medical literature are different from those that occur in dentistry. Significant AEs in the dental office are rare and seldom life threatening. Additionally, with 32 teeth as a starting point and our ability to function well with significantly fewer teeth as well as our ability to replace lost teeth, the attitude towards accidently injuring a tooth has been quite different from doing so with any other body part. Our results suggest the feasibility of the use of a classification system in helping to organize the different types of AEs that patients may encounter through dental treatment. It is important to realize the difference between harm and contributing factors that may lead to harm, e.g., aspiration of a gold onlay is the actual harm, whereas not using a rubber dam, or unexpected movement of the patient would be contributing factors.

There were challenges in classifying some of the AE cases we encountered in our chart review. In our study the reviewers were asked to pick the single best category to describe the AE. However, we discovered that some AEs could be classified into multiple categories, e.g, a patient presenting with swelling and significant pain two days after periodontal flap surgery could be classified under “Pain” as well as “Infection”. While restricting the classification to only one category is useful for reporting purposes, this approach may not fully capture the nature of the harm, which is a limitation of our approach. In some cases our chart reviewers reported that there was insufficient information to classify an AE, e.g., radiographs could be helpful to determine if a peri-apical abscess is new or pre-dated restorative treatment. This speaks to the importance of having adequate clinical documentation that can be used to assess the quality and safety of dental care.30

Our severity scale was adapted from one developed by NCC-MERP to classify medication-related adverse events.23 The severity of harm in dentistry is qualitatively different from that in medicine. While medicine is focused on cases of severe harm (such as death or requiring hospitalization), the most harm that occurs in dentistry is less life altering. Hence, we not only elected to capture harm that is either permanent (extraction of the wrong tooth) or temporary (sinus perforation) but also further divided the harm into slight or moderate/severe in an effort to better distill the most severe cases. We did not explore cases indicated as slight or minimal harm as we believe that in this first effort focusing on more severe harm will help us ultimately undercover underlying systems that can be improved to prevent these more extreme forms of harm from happening again.

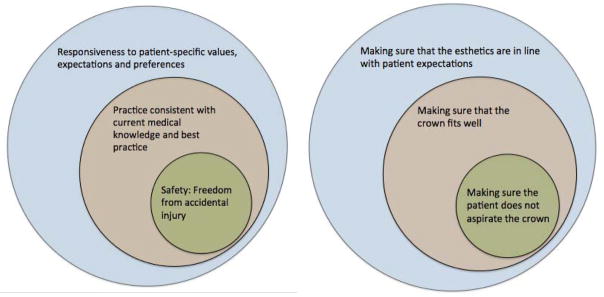

The patient safety revolution can be traced to the seminal Institute of Medicine (IOM) seminal report, “To Err is Human.” It states that quality consist of three domains; 1) safety, defined as “freedom from accidental injury”; 2) practice consistent with current medical knowledge and best practice; and 3) responsiveness to customer-specific values, expectations and preferences.31 We have visually presented these concepts contextualized for the dental profession in Figure 2. All of these elements must be met in order to achieve quality. Assessing adherence to best practices such as percentages of patients having annual dental visits is an important marker, but not a substitute for assessing safety. There must be markers to assess patient safety so that trends can be observed, reported, and used to improve quality.

Figure 2.

Patient safety is a core component of quality of care. (Institute of Medicine (2000) To Err Is Human37)

A hypothetical illustration of safety as a component of quality dental care delivery using tooth crowns. The smallest circle represents the attempt to keep the patient free from accidental injury by ensuring the patient does not aspirate the crown. This fits into the bigger circle of quality by ensuring the crown is functional. The last piece of quality is to ensure that it meets the patient’s preference and aesthetic expectations.

Reporting of AEs is a crucial step for any organization or profession to learn from its mistakes and move toward the establishment of a learning organization32 or profession. Reporting of AEs, however, does not improve safety in and of itself. An AE must be much more than a report. It should lead to exploring underlying systems failures, ultimately leading to change.15 Individuals as well as organizations will gain more from reporting AEs when their information is aggregated and compared to others so that learning can occur across settings to prevent or minimize the probability of recurrences of the same or similar AEs.15

Our extensive study of adverse events in both dentistry and medicine underscores that safety and quality cannot be separated. The absence of quality benchmarking in dentistry that is made available to the public is remarkable when compared to medicine. Meaningful use data is an exemplar. When the US Government committed $27 billion to incentivize the adoption of meaningful use data through the 2009 Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act, dentists were included with physicians as eligible participants. Of the 141,910 providers enrolled in the Medicaid portion of meaningful use (MU) that was relevant for outpatient dentistry33, 15,213 (21%) were dentists. These dentists have received $333,557,837 (9%) in MU incentive pay, however, it appears that the majority of them have participated only for the first year of MU, but not for the following years that will require reporting of nine Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs)34 and twenty Objectives. By contrast,35 73 percent of physicians are participating in the portions of MU that require CQM and Objective reporting.”36 In addition, 95,170 medical providers make up 67% of Medicaid MU enrollees. They received $2,598,954,521 or 69% of the Medicaid portion of the program, with the remainder being paid out to midwives, optometrists, physician assistants and nurse practitioners.35 Myriad reasons might explain why relatively few dentists are participating in the subsequent years of MU. Our concern is that the adoption of a patient safety must not mirror the MU example wherein providers’ participation was short-term. The patient safety paradigm in dentistry must be a long-term commitment by individual providers and the professional at large.

Classifying AEs, categorizing their severity, and eventually standardizing how AEs are captured in databases for query, are key factors to the development of a learning profession. Medicine has accomplished many of these tasks. While dentistry has only begun embracing a patient safety paradigm, it does not have to take the long road that our medical colleagues have traveled. We can learn from their triumphs and strive towards the creation of a learning profession by not only agreeing that patient safety is the first element of quality, but also adopt a standardized classification of adverse events and level of harm as a crucial ingredient in the development of this endeavor.

CONCLUSION

Patient safety is a critical component of quality, and classifying adverse events (AEs) and their severity is an important step towards the ability to analyze patient safety data in a meaningful way. The use of dental AE type and severity classifications facilitate the categorization of and communication about dental AEs during routine chart reviews.

Table 3.

Dental Triggers Showing Reviewed Charts (3283 charts were triggered with specific triggers and 91,936 with a random sample of charts)

| Triggers | # Triggered Charts | #Reviewed Charts |

|---|---|---|

| T1:Extraction Following RCT/Crown/Filling | 110 | 99 |

| T2: Untreated Periodontitis | 224 | 100 |

| T3: Failed Implant | 34 | 34 |

| T4 : Post-surgical extraction complications or Post Perio TX complications | 377 | 100 |

| T5: Repeated Fillings | 391 | 129 |

| T6: Multiple Visits | 60 | 58 |

| T7:Random Charts | 91936 | 99 |

| T8 : Nerve Injury | 36 | 36 |

| T9: Infections | 430 | 100 |

| T10: Soft tissue injury/inflammation | 1449 | 100 |

| T11: Allergy/Toxicity/Foreign Body response | 36 | 35 |

| T12: Aspiration/Ingestion of Foreign Body | 136 | 68 |

| Total | 3283 (+91936) | 958 |

Box 1. Dental Triggers Examples.

| Trigger name | Trigger description | AEs detected |

|---|---|---|

| Allergy or Toxicity or Foreign body response | Patients who had “foreign body” text in their notes and had received at least one treatment in the given calendar year | Allergic reaction to orthodontic brackets, or medication |

| Aspiration or Ingestion of foreign body | Patients who had terms like “aspiration”, “aspirated” in their notes and had received at least one treatment in the given calendar year. | Ingestion or Aspiration of crown or screw during placement of restoration |

| Failed implant | Patients who had a failed implant diagnosis or implant removal procedure code on any tooth in the given calendar year. | Peri-implantitis, lack of implant integration |

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SUPPORT

This research was supported in part by an NIDCR 1R01DE022628-01A1 protocol.

We greatly appreciate the unwavering support and advice of Dr. Lucian Leape and the invaluable feedback from our Advisory Committee members including Drs. Eric Thomas, Joan Ash, John Valenza, Debora Simmons, Ana Karina Mascerenhas, Roger Resar, Ms. Linda Kenney and Mr. Michael Cohen.

Appendices: Classifying Adverse Events in the Dental Setting

Appendix 1: Oral Health Related Terms (86 Terms) Taken From National Cancer Institute’s CTCAE Terminology (679 Terms)

| Level of Harm; Grade 1 = least and 5 = most | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Ear pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Cheilitis | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL; intervention indicated | - | - |

| Dental caries | One or more dental caries, not involving the root | Dental caries involving the root | Dental caries resulting in pulpitis or periapical abscess or resulting in tooth loss | - | - |

| Dry mouth | Symptomatic (e.g., dry or thick saliva) without significant dietary alteration; unstimulated saliva flow >0.2 ml/min | Moderate symptoms; oral intake alterations (e.g., copious water, other lubricants, diet limited to purees and/or soft, moist foods); unstimulated saliva 0.1 to 0.2 ml/min | Inability to adequately aliment orally; tube feeding or TPN indicated; unstimulated saliva <0.1 ml/min | - | - |

| Gingival pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain interfering with oral intake | Severe pain; inability to aliment orally | - | - |

| Lip pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Mucositis oral | Asymptomatic or mild symptoms; intervention not indicated | Moderate pain; not interfering with oral intake; modified diet indicated | Severe pain; interfering with oral intake | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Nausea | Loss of appetite without alteration in eating habits | Oral intake decreased without significant weight loss, dehydration or malnutrition | Inadequate oral caloric or fluid intake; tube feeding, TPN, or hospitalization indicated | - | - |

| Oral cavity fistula | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Symptomatic; altered GI function | Severely altered GI function; TPN or hospitalization indicated; elective operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Oral dysesthesia | Mild discomfort; not interfering with oral intake | Moderate pain; interfering with oral intake | Disabling pain; tube feeding or TPN indicated | - | - |

| Oral hemorrhage | Mild; intervention not indicated | Moderate symptoms; medical intervention or minor cauterization indicated | Transfusion, radiologic, endoscopic, or elective operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Oral pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Periodontal disease | Gingival recession or gingivitis; limited bleeding on probing; mild local bone loss | Moderate gingival recession or gingivitis; multiple sites of bleeding on probing; moderate bone loss | Spontaneous bleeding; severe bone loss with or without tooth loss; osteonecrosis of maxilla or mandible | - | - |

| Salivary duct inflammation | Slightly thickened saliva; slightly altered taste (e.g., metallic) | Thick, ropy, sticky saliva; markedly altered taste; alteration in diet indicated; secretion-induced symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Acute salivary gland necrosis; severe secretion-induced symptoms (e.g., thick saliva/oral secretions or gagging); tube feeding or TPN indicated; limiting self care ADL; disabling | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Salivary gland fistula | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Symptomatic; altered GI function; tube feeding indicated | Severely altered GI function; hospitalization indicated; elective operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent operative intervention indicated | Death |

| Tooth development disorder | Asymptomatic; hypoplasia of tooth or enamel | Impairment correctable with oral surgery | Maldevelopment with impairment not surgically correctable; disabling | - | - |

| Tooth discoloration | Surface stains | - | - | - | - |

| Toothache | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Vomiting | 1 – 2 episodes (separated by 5 minutes) in 24 hrs | 3 – 5 episodes (separated by 5 minutes) in 24 hrs | >=6 episodes (separated by 5 minutes) in 24 hrs; tube feeding, TPN or hospitalization indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Edema face | Localized facial edema | Moderate localized facial edema; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe swelling; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Facial pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Fatigue | Fatigue relieved by rest | Fatigue not relieved by rest; limiting instrumental ADL | Fatigue not relieved by rest, limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Fever | 38.0 – 39.0 degrees C (100.4– 102.2 degrees F) | >39.0 – 40.0 degrees C (102.3– 104.0 degrees F) | >40.0 degrees C (>104.0 degrees F) for <=24 hrs | >40.0 degrees C (>104.0 degrees F) for >24 hrs | Death |

| Injection site reaction | Tenderness with or without associated symptoms (e.g., warmth, erythema, itching) | Pain; lipodystrophy; edema; phlebitis | Ulceration or necrosis; severe tissue damage; operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Localized edema | Localized to dependent areas, no disability or functional impairment | Moderate localized edema and intervention indicated; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe localized edema and intervention indicated; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Neck edema | Asymptomatic localized neck edema | Moderate neck edema; slight obliteration of anatomic landmarks; limiting instrumental ADL | Generalized neck edema (e.g., difficulty in turning neck); limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Allergic reaction | Transient flushing or rash, drug fever <38 degrees C (<100.4 degrees F); intervention not indicated | Intervention or infusion interruption indicated; responds promptly to symptomatic treatment (e.g., antihistamines, NSAIDS, narcotics); prophylactic medications indicated for <=24 hrs | Prolonged (e.g., not rapidly responsive to symptomatic medication and/or brief interruption of infusion); recurrence of symptoms following initial improvement; hospitalization indicated for clinical sequelae (e.g., renal impairment, pulmonary infiltrates) | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Anaphylaxis | - | - | Symptomatic bronchospasm, with or without urticaria; parenteral intervention indicated; allergy-related edema/angioedema; hypotension | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Autoimmune disorder | Asymptomatic; serologic or other evidence of autoimmune reaction, with normal organ function; intervention not indicated | Evidence of autoimmune reaction involving a non-essential organ or function (e.g., hypothyroidism) | Autoimmune reactions involving major organ (e.g., colitis, anemia, myocarditis, kidney) | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Cranial nerve infection | - | - | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Device related infection | - | - | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Gum infection | Local therapy indicated (swish and swallow) | Moderate symptoms; oral intervention indicated (e.g., antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Infective myositis | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Joint infection | - | Localized; local intervention indicated; oral intervention indicated (e.g., antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral); needle aspiration indicated (single or multiple) | Arthroscopic intervention indicated (e.g., drainage) or arthrotomy (e.g., open surgical drainage) | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Lymph gland infection | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Mucosal infection | Localized, local intervention indicated | Oral intervention indicated (e.g., antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Otitis media | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Periorbital infection | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Pharyngitis | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Salivary gland infection | - | Moderate symptoms; oral intervention indicated (e.g., antibiotic, antifungal, antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Sinusitis | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic, endoscopic, or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Soft tissue infection | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Tooth infection | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Wound infection | - | Localized; local intervention indicated (e.g., topical antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral) | IV antibiotic, antifungal, or antiviral intervention indicated; radiologic or operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Infections and infestations - Other, specify | Asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate; minimal, local or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental ADL | Severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self care ADL | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Bruising | Localized or in a dependent area | Generalized | - | - | - |

| Burn | Minimal symptoms; intervention not indicated | Medical intervention; minimal debridement indicated | Moderate to major debridement or reconstruction indicated | Life-threatening consequences | Death |

| Fracture | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Symptomatic but non-displaced; immobilization indicated | Severe symptoms; displaced or open wound with bone exposure; disabling; operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Intraoperative head and neck injury | Primary repair of injured organ/structure indicated | Partial resection of injured organ/structure indicated | Complete resection or reconstruction of injured organ/structure indicated; disabling | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Wound complication | Incisional separation of <=25% of wound, no deeper than superficial fascia | Incisional separation >25% of wound; local care indicated | Hernia without evidence of strangulation; fascial disruption/dehiscence; primary wound closure or revision by operative intervention indicated | Hernia with evidence of strangulation; major reconstruction flap, grafting, resection, or amputation indicated | Death |

| Wound dehiscence | Incisional separation of <=25% of wound, no deeper than superficial fascia | Incisional separation >25% of wound with local care; asymptomatic hernia or symptomatic hernia without evidence of strangulation | Fascial disruption or dehiscence without evisceration; primary wound closure or revision by operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; symptomatic hernia with evidence of strangulation; fascial disruption with evisceration; major reconstruction flap, grafting, resection, or amputation indicated | Death |

| INR increased | >1 – 1.5 × ULN; >1 – 1.5 times above baseline if on anticoagulation | INR increased | >1 – 1.5 × ULN; >1 – 1.5 times above baseline if on anticoagulation | INR increased | >1 – 1.5 × ULN; >1 – 1.5 times above baseline if on anticoagulation |

| Anorexia | Loss of appetite without alteration in eating habits | Oral intake altered without significant weight loss or malnutrition; oral nutritional supplements indicated | Associated with significant weight loss or malnutrition (e.g., inadequate oral caloric and/or fluid intake); tube feeding or TPN indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Arthralgia | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Arthritis | Mild pain with inflammation, erythema, or joint swelling | Moderate pain associated with signs of inflammation, erythema, or joint swelling; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain associated with signs of inflammation, erythema, or joint swelling; irreversible joint damage; disabling; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Avascular necrosis | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Symptomatic; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL; elective operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Exostosis | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Symptomatic; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL; elective operative intervention indicated | - | - |

| Fibrosis deep connective tissue | Mild induration, able to move skin parallel to plane (sliding) and perpendicular to skin (pinching up) | Moderate induration, able to slide skin, unable to pinch skin; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe induration; unable to slide or pinch skin; limiting joint or orifice movement (e.g. mouth, anus); limiting self care ADL | Generalized; associated with signs or symptoms of impaired breathing or feeding | Death |

| Head soft tissue necrosis | - | Local wound care; medical intervention indicated (e.g., dressings or topical medications) | Operative debridement or other invasive intervention indicated (e.g., tissue reconstruction, flap or grafting) | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Myalgia | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Myositis | Mild pain | Moderate pain associated with weakness; pain limiting instrumental ADL | Pain associated with severe weakness; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Osteonecrosis of jaw | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Symptomatic; medical intervention indicated (e.g., topical agents); limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL; elective operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Trismus | Decreased ROM (range of motion) without impaired eating | Decreased ROM requiring small bites, soft foods or purees | Decreased ROM with inability to adequately aliment or hydrate orally | - | - |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (incl cysts and polyps) - Other, specify | Asymptomatic or mild symptoms; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate; minimal, local or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental ADL | Severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self care ADL | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Dysgeusia | Altered taste but no change in diet | Altered taste with change in diet (e.g., oral supplements); noxious or unpleasant taste; loss of taste | - | - | - |

| Facial muscle weakness | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Facial nerve disorder | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Glossopharyngeal nerve disorder | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Headache | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Hypoglossal nerve disorder | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Paresthesia | Mild symptoms | Moderate symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Sinus pain | Mild pain | Moderate pain; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe pain; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Syncope | - | - | Fainting; orthostatic collapse | - | - |

| Trigeminal nerve disorder | Asymptomatic; clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated | Moderate symptoms; limiting instrumental ADL | Severe symptoms; limiting self care ADL | - | - |

| Epistaxis | Mild symptoms; intervention not indicated | Moderate symptoms; medical intervention indicated (e.g., nasal packing, cauterization; topical vasoconstrictors) | Transfusion, radiologic, endoscopic, or operative intervention indicated (e.g., hemostasis of bleeding site) | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Sleep apnea | Snoring and nocturnal sleep arousal without apneic periods | Moderate apnea and oxygen desaturation; excessive daytime sleepiness; medical evaluation indicated; limiting instrumental ADL | Oxygen desaturation; associated with hypertension; medical intervention indicated; limiting self care ADL | Cardiovascular or neuropsychiatric symptoms; urgent operative intervention indicated | Death |

| Erythema multiforme | Target lesions covering <10% BSA and not associated with skin tenderness | Target lesions covering 10 – 30% BSA and associated with skin tenderness | Target lesions covering >30% BSA and associated with oral or genital erosions | Target lesions covering >30% BSA; associated with fluid or electrolyte abnormalities; ICU care or burn unit indicated | Death |

| Bullous dermatitis | Asymptomatic; blisters covering <10% BSA | Blisters covering 10 – 30% BSA; painful blisters; limiting instrumental ADL | Blisters covering >30% BSA; limiting self care ADL | Blisters covering >30% BSA; associated with fluid or electrolyte abnormalities; ICU care or burn unit indicated | Death |

| Periorbital edema | Soft or non-pitting | Indurated or pitting edema; topical intervention indicated | Edema associated with visual disturbance; increased intraocular pressure, glaucoma or retinal hemorrhage; optic neuritis; diuretics indicated; operative intervention indicated | - | - |

| Stevens-Johnson syndrome | - | - | Skin sloughing covering <10% BSA with associated signs (e.g., erythema, purpura, epidermal detachment and mucous membrane detachment) | Skin sloughing covering 10 – 30% BSA with associated signs (e.g., erythema, purpura, epidermal detachment and mucous membrane detachment) | Death |

| Hematoma | Mild symptoms; intervention not indicated | Minimally invasive evacuation or aspiration indicated | Transfusion, radiologic, endoscopic, or elective operative intervention indicated | Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Hypertension | Prehypertension (systolic BP 120 – 139 mm Hg or diastolic BP 80 – 89 mm Hg) | Stage 1 hypertension (systolic BP 140 – 159 mm Hg or diastolic BP 90 – 99 mm Hg); medical intervention indicated; recurrent or persistent (>=24 hrs); symptomatic increase by >20 mm Hg (diastolic) or to >140/90 mm Hg if previously WNL; monotherapy indicated Pediatric: recurrent or persistent (>=24 hrs) BP >ULN; monotherapy indicated | Stage 2 hypertension (systolic BP >=160 mm Hg or diastolic BP >=100 mm Hg); medical intervention indicated; more than one drug or more intensive therapy than previously used indicated Pediatric: Same as adult | Life-threatening consequences (e.g., malignant hypertension, transient or permanent neurologic deficit, hypertensive crisis); urgent intervention indicated Pediatric: Same as adult | Death |

| Hypotension | Asymptomatic, intervention not indicated | Non-urgent medical intervention indicated | Medical intervention or hospitalization indicated | Life-threatening and urgent intervention indicated | Death |

| Phlebitis | - | Present | - | - | - |

Appendix 2: Overlap Of Five Medical Approaches To Observing Adverse Events

| National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v 4.0 (CTCAE) |

Harvard Medical Practice Study |

IHI Outpatient Trigger Tool |

WHO International Classification for Patient Safety (ICPS) |

Medicare Hospital- Acquired Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders |

|

|

||

| Cardiac disorders | ||||

| Congenital, familial and genetic disorders | ||||

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | ||||

| Endocrine disorders |

|

|||

| Eye disorders | ||||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | ||||

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Diagnostics Medications Miscellaneous |

|

|

|

| Hepatobiliary disorders | ||||

| Immune system disorders | ||||

| Infections and infestations |

|

|

||

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | Procedures |

|

||

| Investigations | Therapeutics |

|

||

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders |

|

|||

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders |

|

|||

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified (incl. cysts and polyps) |

|

|||

| Nervous system disorders | ||||

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | Nepnatal Peripartum | |||

| Psychiatric disorders |

|

|||

| Renal and urinary disorders | ||||

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | ||||

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | Anesthesia | |||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | ||||

| Social circumstances | Falls |

|

||

| Surgical and medical procedures | Operations |

|

|

|

| Vascular disorders |

|

References

- 1.American Dental Association. Dentists: Doctors of Oral Health. Chicago, Ill: American Dental Association; 2015. [Accessed 6/30/2015]. http://www.ada.org/en/about-the-ada/dentists-doctors-of-oral-health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hebballi NB, Ramoni R, Kalenderian E, et al. The dangers of dental devices as reported in the Food and Drug Administration Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience Database. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(2):102–10. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalenderian E, Walji MF, Tavares A, Ramoni RB. An adverse event trigger tool in dentistry: A new methodology for measuring harm in the dental office. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(7):808–14. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramoni R, Walji MF, Tavares A, et al. Open wide: looking into the safety culture of dental school clinics. J Dent Educ. 2014;78(5):745–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramoni RB, Walji MF, White J, et al. From good to better: toward a patient safety initiative in dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143(9):956–60. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thusu S, Panesar S, Bedi R. Patient safety in dentistry - state of play as revealed by a national database of errors. Br Dent J. 2012;213(3):E3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey E, Tickle M, Campbell S. Patient safety in primary care dentistry: where are we now? Br Dent J. 2014;217(7):339–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiivala N, Mussalo-Rauhamaa H, Murtomaa H. Patient safety incidents reported by Finnish dentists; results from an internet-based survey. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71(6):1370–7. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2013.764005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiivala N, Mussalo-Rauhamaa H, Tefke HL, Murtomaa H. An analysis of dental patient safety incidents in a patient complaint and healthcare supervisory database in Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 2015:1–9. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2015.1042040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiivala N, Mussalo-Rauhamaa H, Tefke HL, Murtomaa H. An analysis of dental patient safety incidents in a patient complaint and healthcare supervisory database in Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 2016;74(2):81–9. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2015.1042040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey E, Tickle M, Campbell S, O’Malley L. Systematic review of patient safety interventions in dentistry. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s12903-015-0136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. The conceptual framework for the international classification for patient safety. World Health Organization. 2009;2009:1–149. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ’s Patient Safety Initiative: Building Foundations, Reducing Risk. Chapter 3. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Dec, 2003. AHRQ’s Patient Safety Initiative: Breadth and Depth for Sustainable Improvements. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamalik N, Perea Perez B. Patient safety and dentistry: what do we need to know? Fundamentals of patient safety, the safety culture and implementation of patient safety measures in dental practice. Int Dent J. 2012;62(4):189–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2012.00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.From Information to Action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2005. [Accessed 04/17/2015]. World Alliance for Patient Safety WHO Draft Guidelines for Adverse Event Reporting and Learning Systems. “ http://www.who.int/patientsafety/events/05/Reporting_Guidelines.pdf?ua=1”. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) National Institutes of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):377–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The World Alliance for Patient Safety; World Health Organization, editor. Final Technical Report. Geneva, Switzerland: Jan, 2009. Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety; p. 154. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levinson DR. Adverse Events in Hospitals: National Incidence among Medicare Beneficiaries. Dallas, TX: Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. “ https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-09-00090.pdf”. 96/11/2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Quality Forum (NQF) Serious Reportable Events In Healthcare—Update: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: NQF; 2011. p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Resar R. Outpatient Adverse Event Trigger Tool. Cambridge MA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23. [Accessed 06/18/2015];National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) NCC MERP Taxonomy of Medication Errors. 2001 “ http://www.nccmerp.org/sites/default/files/taxonomy2001-07-31.pdf”.

- 24.Nuckols TK, Bell DS, Liu H, Paddock SM, Hilborne LH. Rates and types of events reported to established incident reporting systems in two US hospitals. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(3):164–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.019901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obadan E, Ramoni RB, Kalenderian E. Lessons Learned from Dental Patient Safety Case Reports. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2015;146(5):318–26. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maramaldi P, Walji MF, White J, et al. How dental team members describe adverse events. The Journal of the American Dental Association. 2016;147(10):803–11. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. biometrics. 1977:159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cunningham M. More than just the kappa coefficient: a program to fully characterize inter-rater reliability between two raters. Paper presented at: SAS global forum; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leong P, Afrow J, Weber HP, Howell H. Attitudes toward patient safety standards in U.S. dental schools: a pilot study. Journal of Dental Education. 2008;72(4):431–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tokede O, Ramoni RB, Patton M, Da Silva JD, Kalenderian E. Clinical documentation of dental care in an era of electronic health record use. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice. 2016;16(3):154–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Healthcare System. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senge PM. The fifth discipline : the art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency; 2006. Rev. and updated. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalenderian E, Walji M, Ramoni RB. “Meaningful use” of EHR in dental school clinics: how to benefit from the U.S. HITECH Act’s financial and quality improvement incentives. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(4):401–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Eligible Professional Meaningful Use Core Measures. Stage 2. Washington, DC: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2014. Measure 7 of 17. “ http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/downloads/Stage2_EPCore_7_PatientElectronicAccess.pdf”. [Google Scholar]

- 35.EHR Incentive Payment. CMS; 2015. [Accessed 06/21/2015]. “ http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/April2015_SummaryReport.pdf”. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Office of the National Coordinatoror Health Information Technology Fast Facts about Health IT Adoption in Health Care. Percent of REC Enrolled Providers by Practice Type Live on an EHR and Demonstrating Meaningful Use. Washington, DC: 2015. [Accessed 06/21/2015]. “ http://dashboard.healthit.gov/quickstats/.”. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]