Abstract

Objectives

An interprofessional group of health colleges’ faculty created and piloted the Barriers to Error Disclosure Assessment (BEDA) Tool, as an instrument to measure barriers to medical error disclosure among health care providers.

Methods

A review of the literature guided the creation of items describing influences on the decision to disclose a medical error. Local and national experts in error disclosure used a modified Delphi process to gain consensus on the items included in the pilot. After receiving University Institutional IRB approval researchers distributed the tool to a convenience sample of physicians (n = 19), pharmacists (n=20), and nurses (n=20) from an academic medical center. Means and standard deviations were used to describe the sample. Intra-class correlations (ICCs) were used to examine test-retest correspondence between the continuous items on the scale. Factor analysis with Varimax rotation was used to determine factor loadings and examine internal consistency reliability. Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated during initial and subsequent administrations to assess test-retest reliability.

Results

After omitting two items with intra-class correlations < 0.40, ICCs ranged from 0.43–0.70 indicating fair to good test-retest correspondence between the continuous items on the final draft. Factor analysis revealed the following factors during the initial administration: confidence and knowledge barriers, institutional barriers, psychological barriers, and financial concern barriers to medical error disclosure. Alpha coefficients of 0.85–0.93 at time 1 and 0.82–0.95 at time 2 supported test-retest reliability.

Conclusions

The final version of the 31-item tool can be used to measure perceptions about abilities for disclosing, impressions regarding institutional policies and climate, and specific barriers that inhibit disclosure by health care providers. Preliminary evidence supports the tool’s validity and reliability for measuring disclosure variables.

Keywords: Medical error disclosure, patient safety, interprofessional collaboration, barriers

Introduction

Medical Error Disclosure

There are more than 400,000 deaths per year due to medical error, trailing only heart disease and cancer in prevalence.1 Despite availability of patient safety guidelines and treatment protocols, medical errors still occur.2 The National Quality Forum, The Joint Commission, and the Institute of Medicine recommend medical error reporting as a strategy for providing information that can improve healthcare quality and safety.2–4 Correspondingly, patients, healthcare organizations, and professional codes of ethics advocate for disclosure of medical errors in order to provide transparent information to patients regarding all aspects of their care.5–9 Medical error reporting and disclosure are different processes; medical error disclosure is the focus of this paper. Fein et al. 10 proposed a useful definition of error disclosure in their focus group study eliciting opinions and observations from physicians, nurses and administrators:

ERROR DISCLOSURE refers to communication between a health care provider and a patient, family members, or the patient’s proxy that acknowledges the occurrence of an error, discusses what happened, and describes the link between the error and outcomes in a manner that is meaningful to the patient (page 760).

With patient safety being a primary focus of the World Health Organization, hospitals are increasingly assessing their organizational safety cultures with disclosure as one element.5,11,12 In addition, the Leapfrog Group, a national not-for-profit organization, developed a standardized method to evaluate patient safety in US hospitals through creating a composite safety score.13 In terms of a principle marker of quality, the Leapfrog Group advocates for organizational culture that promotes reporting, transparency, and disclosure. For example, one element of the survey provides guiding language regarding open communication with patients and sincere apology for medical error, citing the Mass Coalition for the Prevention of Medical Errors that “a sincere apology from responsible hospital staff can help heal the breach of trust between doctor/hospital and patient.” 13

Research demonstrates that while clinicians desire transparency and full disclosure, these attitudes are often not translated into practice, and when disclosure does occur, it typically falls short of patient or family expectations.5,11,14,15 Barriers impeding disclosure transparency are numerous, with communication inexperience and lack of training commonly cited.16 While providers may lack confidence in their communication abilities and in their knowledge of how to conduct an effective disclosure, research shows that ineffective communication between providers and patients is the single most significant factor in explaining why patients litigate.17 In a study of medical negligence claims, 91% of the patients exposed to error indicated that the “desire for an explanation” was a reason to litigate.18 Patients undertaking legal action wanted greater honesty, an appreciation of the severity of the trauma they had suffered, and assurances that lessons had been learned from their experiences.18 The decision to take legal action was determined not only by the original injury, but also by insensitive handling and poor communication after the original incident.18

Approaches that have been shown to increase transparency and improve communication and completeness of disclosure to patients and their family members may positively influence care delivery, particularly if greater patient satisfaction and improved institutional cultures of safety ensue.2,4,11,14,15 In a study of root cause analysis processes following an adverse event during hospitalization, patients and family members expressed a desire to be involved in the post-event analysis when the restructuring process was patient centered.19 Participant suggestions for process improvement included offering multiple ways for patients to provide feedback, protecting the legal rights of patients and health care providers during analysis procedures, interviewing patients and families about the event, and selecting optimal times for having disclosure discussions, preferably when emotional and physical distress are low.19

Barriers to Disclosure

Decreased confidence and having a limited understanding of best practices may limit disclosure when providers are unsure about their skill or knowledge levels for the task.16, 20 Communication inexperience and/or lack of disclosure training are recognized obstacles to effective error disclosure.16,21,22 Skillful communication and mastery of verbal and nonverbal cues are imperative to productive disclosure practices. Attentive and expressive nonverbal cues by health care providers during error disclosure are linked to greater patient perceptions of apology sincerity, higher quality explanations, and appropriate remorse from their provider in a sample of patients receiving outpatient care.21 Verbal and nonverbal communication skills are taught within health professions curricula, but in the absence of curricula that are reinforced throughout the clinical training years, trainees “unlearn” skills needed to respond to error competently, empathetically, and responsibly.11

Institutional barriers to disclosure include unsupportive institutional cultures and unclear guidelines for action when encountering an error.5,14,22,23 Psychological variables such as fear of disciplinary action, shame, guilt, and embarrassment can impact disclosure decisions.5,20,22,24 Additionally, concern about losing patients’ trust and colleagues’ support and respect can prohibit disclosure when errors in care occur. 5,14,20

Concerns about the financial aspects of medical error disclosure can also influence decisions to disclose. The possibility of litigation, fear of losing malpractice insurance, or the potential for increased malpractice insurance premiums are identified barriers to disclosure among health care providers.5,24–26

Improving Disclosure Methods

One strategy to promote effective medical error disclosure is the consistent provision of healthcare provider education and training. Providing disclosure training for health care providers and promoting a culture of transparency in the workplace show promise for improving medical error disclosure. 15,27–29 Research demonstrates that focused training in error disclosure improves trainees’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes in disclosing medical errors.15, 27–29 Team-based care improves patient outcomes and is an expectation in healthcare delivery;16, 30–35 subsequently, all members of the healthcare team are vulnerable to medical error. Therefore, interventions to improve medical error disclosure should be designed for all professionals who provide care.

A crucial first step for developing educational interventions to improve medical error disclosure is the systematic identification of the barriers practitioners face when disclosure is warranted. Moreover, quantification of the magnitude of a barrier when it exists can guide the prioritization of individual or institutional interventions to promote effective disclosure and facilitate medical error research. A review of the literature to locate a tool for identifying and quantifying barriers yielded no results. Consequently, a group of faculty members from medicine, nursing, and pharmacy collaborated with health care attorneys to create a tool to measure barriers to error disclosure, the Barriers to Error Disclosure Assessment (BEDA) Tool. Strategies used during BEDA Tool development, items comprising the tool, and the psychometric proprieties of the instrument during initial pilot testing are described.

Methods

Literature Review

Disclosure barriers were identified and selected for inclusion on the BEDA tool based on information from articles and publications identified through a literature search pertaining to patient safety and error disclosure. For this study, PubMed, Web of Science, and LexisNexis academic databases were searched using the key words “medical error disclosure,” “ethics of disclosure,” “barriers” AND “disclosure,” and “disclosure transparency,” with a date limit of 1980 and beyond. Searches were limited to inclusion of publications in the English language only and geographically to the United States, Canada, and England. Sources of information were limited to law reviews and journals, academic and medical journals, patient safety journals, and web-based publications from national healthcare quality and safety organizations.

The primary investigator reviewed titles and abstracts of retrieved articles to identify relevant publications. Publications were included only if they identified or discussed barriers that impact healthcare provider willingness or ability to disclose errors. The literature search was continued until saturation or a “point of minimal return” was reached.

Tool Construction

From the literature, a list of healthcare provider disclosure barriers, beliefs, and perceptions was generated, and a modified Delphi process36 involving a panel of experts was used to reach consensus regarding the specific content to include on the survey. The reason the Delphi technique was employed is two-fold: (1) barriers described in the literature are primarily from a physician perspective. Our population of interest included nurses, physicians, and pharmacists; and, (2) the literature describes a myriad of attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions regarding disclosure that may or may not necessarily represent a barrier to disclosure. Thus for the sake of clarity, the over-arching objective of utilizing the Delphi process was to reach consensus on defining barriers for the BEDA tool so that the tool could ultimately be used to measure the impact of an educational intervention on reducing healthcare provider barriers to disclosure.

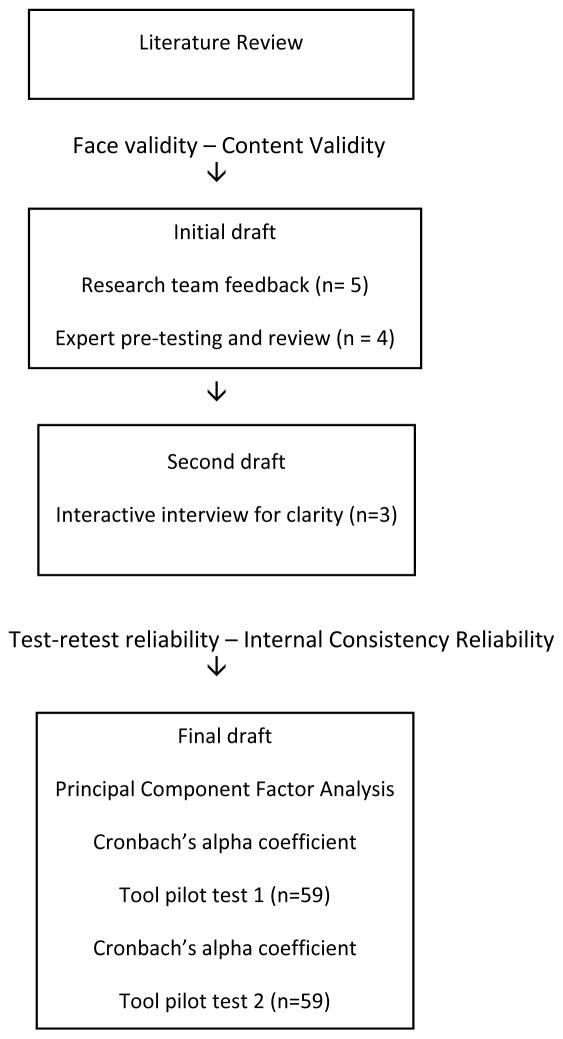

The Delphi technique is a structured process for gathering information from respondents within their domain of expertise and is a well-suited method for consensus-building or for achieving convergence of opinion on a specific topic or issue.36 A series of questionnaires are delivered to respondents with multiple iterations or “rounds” until group consensus on a final version is reached.36,37 Variation in the use of the Delphi technique may be noted among researchers as there are no universally accepted requirements.37 Procedures to explore the reliability and validity of the tool along with a succinct overview of the development process are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of Tool Development Process using a Modified Delphi Process

Delphi Process

Panelists were selected based on their willingness to participate and their knowledge and expertise of the topic.37 Panelists were identified based upon legal expertise, national recognition and/or publications related to disclosure, clinician educator on the topic of disclosure, and service on state or national advocacy boards regarding apology laws and disclosure. Twelve potential panelists were personally contacted by phone and/or email, and individuals were asked if they would be willing to contribute their time and expertise to BEDA Tool development. Nine individuals agreed to participate.

In the first round of the Delphi process, panelists received the initial draft (Appendix, A) and were asked to establish preliminary priorities among items to begin building consensus regarding content. In round 2, panelists received the survey items and feedback of other panelist members summarized by the investigators. Panelists were provided an opportunity to make further clarifications regarding survey items and their judgments of the relative importance of the items. Following this round, the list of remaining items were distributed to panelists in order to provide a final opportunity for participants to revise their judgments, which resulted in 100% consensus in survey content and wording.

Pretesting and Interactive Interviews

Following three rounds of the Delphi process, the tool was then reviewed by an independent panel of experts located in different regions of the U.S. (n=5) for pre-testing and further refinement. The same four criteria for “expert” panel participation were used at this stage. Suggestions from this panel are incorporated into Table 1. Following pre-testing the tool underwent interactive interview for purposes of question clarity, at which point no further suggestions were made.

Table 1.

Specific Changes to Tool During Development

| Preliminary drafts | Panel Recommendations | Completed Revisions |

|---|---|---|

| Primary literature review for barriers to disclosure | ||

| Twelve-item questionnaire based on 5-item Likert scale of agreement regarding barriers impacting willingness to disclose | ||

| Instructions: “Rate your agreement with the following statements regarding your attitudes toward disclosing a medical error to patients or their significant others. With this tool, medical error refers to an error made by any member of the healthcare team during patient care delivery.” | ||

| Internal Expert Panel Review | ||

| Add demographics at beginning of survey. | Added demographics to include gender, professional discipline, highest terminal degree earned and others | |

| Determine if participants have ever disclosed a medical error. | Added: “Have you ever personally disclosed a medical error to a patient, patient’s family, or patient’s significant other?” | |

| Determine if participants have ever disclosed a medical error as part of an interprofessional team. | Added “Have you ever disclosed a medical error with a team of other healthcare professionals?” | |

| Determine if participants have ever received formal disclosure training. If so, when and what content was covered? | Added, “Have you received formal training in medical error disclosure?” For those who answer “yes,” added: “Where did you receive disclosure training?” (check all that apply) “What content areas were covered in your disclosure training? (check all that apply) “What content in your error disclosure training have you found particularly helpful to your professional practice?” (open response) “What specific aspects regarding medical error disclosure would be helpful for you to learn more about?” (open response) |

|

| Determine if participants have ever had prior training disclosing an error as a member of an interprofessional team (i.e. prior training in team disclosure). | Added “disclosure as an interprofessional team” as an answer choice “I” for question regarding content areas covered in prior disclosure training. | |

| Explain purpose of survey. | Added, “This survey will collect data related to your current practice experience, degree of training related to medical error disclosure, and current comfort level in disclosing medical errors. This survey also asks questions to determine the degree to which known barriers may impact your ability or willingness to disclose medical errors to patients and/or their significant others. Data gathered from this survey will guide and inform the development of an error disclosure training curriculum. Data collected will provide a baseline by which to compare the outcome of the curriculum. Your responses are confidential. You may choose to skip any question you are not comfortable answering.” | |

| Divide survey into two parts: Part 1 related to demographics and Demographics and Part 2 related to attitudes, perceptions, and barriers. Change survey instructions to correlate to each part. | Deleted original instructions. For demographic section added, “The first set of questions are related to your current practice experience and the degree of training you may have received in medical error disclosure. You may skip any question you are not comfortable answering.” For attitudes and barriers section added, ““The last set of questions are related to barriers you may feel that impact your ability or willingness to disclose errors to patients, family members, or their significant others. Rate your level of agreement with the following statements. You may skip any question you are not comfortable answering or that you believe do not apply to you.” |

|

| Define “Error Disclosure.” | Added: “Error Disclosure refers to communication between a health care provider and a patient, family members or the patient’s proxy that acknowledges the occurrence of an error, discusses what happened, and describes the link between the error and outcomes in a manner that is meaningful to the patient.”1 | |

| Define “Medical Error.” | Added: “Medical Error refers to error(s) made by any member of the healthcare team during patient care delivery and is defined by the Institute of Medicine as the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (error of execution) or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (error of planning). The subset of medical errors pertaining to this survey are those that result in patient harm.”2 | |

| Add questions regarding terminal professional degree earned for each participant. | For nurse, added: “What is your highest nursing degree earned?” For pharmacist, added: “What is your terminal pharmacy degree?” For physician, added: “What is your terminal medical degree?” |

|

| “I am confident in my ability to offer an effective apology in terms of disclosing a medical error to a patient.” | The primary focus of the research is on disclosing an error. Apology is one element of disclosure. Suggest rephrasing statement to determine if participants are confident in their ability to disclose an error, because one can offer an apology without actually admitting to an error. | Rephrased as, “I am confident in my ability to disclose a medical error.” |

| In addition to confidence, determine participants’ comfort level regarding disclosing an error. | Added, “I am comfortable in my ability to disclose a medical error.” | |

| “Fear of losing colleague respect affects my willingness to disclose a medical error.” “Fear of losing colleague support affects my willingness to disclose a medical error.” |

Respect and support are similar. Differentiating to this degree is not relevant; choose one or the other. | Deleted statement regarding colleague respect. |

| “My employing institution supports disclosure of medical errors by health care providers.” “I receive mixed messages from my employing institution regarding the process of disclosing an error.” “I receive mixed messages from my employing institution regarding what types of errors should be disclosed.” |

Delete “employing.” | Deleted “employing” from all institution-related statements. |

| Determine if participants are aware if their institution provides peer support services for healthcare providers following an error. | Added, “My institution provides peer support services that help providers deal with the emotional consequences of error.” | |

| Determine if participants know their institutional processes of reporting errors. | Added, “I am uncertain about how to report errors/mistakes.” | |

| “The physician should take full responsibility for the error, even when non-physician healthcare providers on the team may have played a role in the error (i.e. “I lead the team; this happened on my watch, therefore my fault.”) | Statement is lengthy. Consider rephrasing, but retain the original belief that physicians bear the ultimate responsibility. | Rephrased to, “The physician is the ultimate one responsible for disclosing the medical error, regardless of his/her involvement in the error.” |

| National Expert Panel Review: Pretest and content validity | ||

| Define “patient harm.” | Added: “Patient Harm is defined by the National Quality Forum as any unintended injury or impairment of the physical, emotional, or psychological function or structure of the body and/or pain resulting from or contributed to by medical care (including the absence of indicated medical treatment) that requires treatment or intervention, initial or prolonged hospitalization, life-sustaining intervention, results in temporary or permanent disability or death.”3 | |

| “What is your terminal pharmacy degree?” “What is your terminal medical degree?” |

Determining terminal degrees/degree distinctions for physicians and pharmacists is likely not relevant. There are no degree designations for foreign graduates. | Deleted both questions. |

| Demographic instructions: “The first set of questions are related to your current practice experience and the degree of training you may have received in medical error disclosure. You may skip any question you are not comfortable answering.” | Recommend moving demographics to the end of the survey. | Moved demographic questions to the end of survey. Rephrased demographic instructions to, “The next set of questions pertain to demographics and practice experience.” |

| Add a question to determine if participants know when to disclose (not just how much to disclose) | On 5-item Likert scale of agreement, added: “I am not sure when I should disclose an error.” | |

| “How many years have you been in practice?” | Clarify what is meant by years in practice. Does this include post-graduate training or not? | “How many years have you been in practice (include your post-graduate training years, if applicable)?” |

| “Have you received formal training in medical error disclosure?” | Define what is meant by “formal” training, or if you are simply interested in whether participants have had any degree of training at all. | Rephrased to, “Have you received any level of training in medical error disclosure?” |

| “Where did you receive disclosure training?” (check all that apply) “What content in your error disclosure training have you found particularly helpful to your professional practice?” (open response) |

Consider the necessity of each question in the survey and what you plan to do with the data once it is received. Suggest determining on gaps in disclosure knowledge/what would be most helpful for participants to learn more about in order to guide your curricular development. | Deleted all questions |

| “What specific aspects regarding medical error disclosure would be helpful for you to learn more about?” (open response) | Suggest providing some choices for participants to help guide them in terms of what you are asking them for and provide a choice for “other” in which participants can further specify information. | Rephrased to, “What specific aspects regarding medical error disclosure would be helpful for you to learn more about?” (check all that apply)

|

| For the questions pertaining to institutional perceptions about disclosure, consider adding a question about transparency and/or an atmosphere of “blame and shame.” You may want to ask this a couple of different ways. This will allow you to further determine and address any misperceptions about the institution in your training program. | Added, “My institution supports an atmosphere of transparency in error disclosure.” Added, “My institution supports an atmosphere of ‘shame and blame’ regarding medical errors.” |

|

| “The last set of questions are related to barriers you may feel that impact your ability or willingness to disclose errors to patients, family members, or their significant others. Rate your level of agreement with the following statements below. You may skip any question you are not comfortable answering or that you believe do not apply to you.” | Some questions are not related to barriers; some are related to knowledge of disclosure and institutional perceptions on disclosure. Recommend to separate these out. For attitudes/perceptions ask on a 5-item Likert scale of agreement. For barriers, ask to what degree participants perceive it is a barrier on a 5-item Likert scale: very much a barrier, somewhat of a barrier, neutral, not much of a barrier, not at all a barrier. This allows you to condense the items to, “fear of litigation, fear of disciplinary action,” etc. Rephrase the directions for these sections to reflect this change. Combine barriers 11 and 12; there is no difference between these two For barriers 3–7 in the directions consider stating: “To what degree do the following pose a barrier in your ability or willingness to disclose an error?” |

Implemented separate sections and separate scale for attitudes/perceptions and barriers. Changed directions for attitudes/perceptions to, “The following statements are related to different aspects of error disclosure. Indicate your degree of agreement with the following statements.” Changed directions for barriers section to, “The following are known barriers within the literature that impact providers’ ability or willingness to disclose a medical error. To what degree to the following pose a barrier in your ability or willingness to disclose an error?” Kept barrier 12 because another reviewer liked that question. Rephrased barrier 11 to “The physician is the ultimate one responsible for disclosing the medical error regardless of his/her involvement in the error.” |

| Given that this survey will be administered to more than one professional group, consider adding more questions about whether participants are aware of their roles/responsibilities in disclosure conversations to determine if there are differences between professions on this item. | Added, “I am unsure of my role in a disclosure conversation with the patient and/or family members.” | |

| Consider determining participant attitudes regarding their own and others’ inclusion in disclosure conversations. Given increasing interest in team-based disclosure, it may be important to determine professional attitudes about the inclusion of themselves and others in these conversations and if there are differences in these attitudes between professions. | Added, “I would like to be included in the error disclosure process in the event I am involved in a medical error.” Added, “Other non-physician healthcare providers (e.g. nurses, pharmacists, etc.) should be included in the disclosure conversation if they contributed to the occurrence of the error.” |

|

| The survey appears to be missing several barriers to disclosure that have been described in the literature. For example, emerging evidence suggests that nurses fear being blamed for an error if they are not present during the disclosure conversation. Consider asking this for all professions participating. Other barriers include fear of losing malpractice insurance, shame, damaged reputation, among many others. | Added, “I am afraid of being blamed for a medical error if I am not present during the disclosure conversation with a patient and/or patient’s family.” Added the following barriers: Fear of personal failure Fear of losing self-esteem Fear of damaged reputation Fear of judgment from colleagues Fear of losing malpractice insurance coverage Fear of increased insurance premiums Fear of shame Fear that peers will question my competence. |

|

| Interactive Interview – no changes recommended | ||

| Final BEDA Tool underwent Pilot Testing (Appendix B) | ||

Fein, S.P., Hilborne, L.H., Spiritus, E.M., Seymann, G.B., Keenan, C.R., Shojania, K.G., Kagawa-Singer, M., Wenger, N.S. (2007). The many faces of error disclosure: A common set of elements and a definition. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22, 755–761. Doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0157-9.

Institute of Medicine (IOM). (1999). To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Quality Forum (NQF). (2009). NQF Patient safety terms and definitions. Retrieved from: https://www.qualityforum.org/Topics/Safety_Definitions.aspx

Pilot Testing

A final draft (Appendix B) of the BEDA tool was constructed and underwent pilot testing for validation. The first four questions collected demographic information regarding respondents’ training needs and experience with medical error disclosure. Other demographics regarding professional role and specialty, education, employing agency, and other institutional specific variables are not described here, because they are specific to the organization. The final version of the BEDA tool includes 15 items describing attitudes about abilities for disclosing, impressions regarding institutional policies and climate for medical error disclosure, and perceptions about professional roles in the process of error disclosure. Respondents rank their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Twelve additional quantitative items describe specific barriers that inhibit disclosure by health care providers; these items are ranked 1 = not a barrier at all to 5 = very much a barrier.

We estimated that a sample size of at least 52 participants was required to measure an Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of 0.8 for two repeated measures, with 95% confidence intervals of width 0.2.38 Twenty nurses, 19 physicians (3 of whom were medical residents in training), and 20 pharmacists (4 of whom were pharmacy residents in training) completed the BEDA tool at two separate points, two weeks apart to examine test-retest reliability and internal consistency reliability. Participants in the pilot received the BEDA tool electronically through REDCap™ (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure, web-based application designed exclusively to support data capture for research studies (REDCap Software - Version 6.4.4 - © 2015 Vanderbilt University).

Data Analysis

Means and standard deviations were used to describe participant responses to quantitative items on the tool. Intra-class correlations (ICCs) were used to assess the test-retest correspondence between continuous items, where >0.75 was excellent, 0.40–0.75 was fair to good, and <0.40 was poor.39 Items 5, 6, 8, 9, 16, and 17 were reverse coded prior to data analysis. Factor analysis was used to examine whether there were groups of items that go together or form a single factor or construct. If items are associated with one factor, they should be correlated with each other, and correlations should go only in one direction or be positively associated with the factor. Principal Component Factor (PCF) was employed as a method of extraction to identify the strength of correlations between items theorized to measure a single factor or construct. Initial solutions were rotated using Varimax orthogonal rotation, which does not allow factors to be correlated with each other, to assess the internal consistency reliability of items 5–31 at time 1 (n=59). Cronbach alpha coefficients were calculated with tool administration at time 1 and time 2 to examine test-retest reliability.

Results

Mean scores were lowest for items measuring confidence (M=2.38, SD = 0.90) and comfort (M =2.44, SD = 0.95) with medical error disclosure. Mean scores were highest for items describing barriers such as fear of losing patient trust (M =3.95, SD = 1.07) and fear of litigation (M =3.85, SD = 1.03). Means and standard deviations for all continuous variables are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factor Analysis and Reliability Results

| Item Number | Variable | Mean | SD | Factor Loading | alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Confidence and Knowledge barriers | 2.90 | 0.81 | 0.86 | |||

| 5. | I am COMFORTABLE in my ability to disclose a medical error. | 2.44 | 0.95 | 0.88 | 0.80 | |

| 6. | I am CONFIDENT in my ability to disclose a medical error. | 2.38 | 0.90 | 0.79 | 0.83 | |

| 7. | I am not sure how much I should disclose to a patient/family member in the event I am involved in a medical error. | 3.50 | 1.08 | 0.82 | 0.82 | |

| 12. | I am not sure when I should disclose an error. | 3.05 | 1.09 | 0.72 | 0.84 | |

| 15. | I am unsure of my role in a disclosure conversation with the patient and/or family members. | 3.09 | 1.07 | 0.76 | 0.83 | |

| Factor 2: Institutional barriers | 2.68 | 0.82 | 0.86 | |||

| 8. | My institution supports an atmosphere of transparency in error disclosure. | 2.45 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.86 | |

| 9. | My institution supports disclosure of medical errors BY HEALTHCARE PROVIDERS. | 2.49 | 0.88 | 0.80 | 0.83 | |

| 10. | I receive mixed messages from my institution regarding THE PROCESS of disclosing an error. | 2.88 | 1.08 | 0.90 | 0.78 | |

| 11. | I receive mixed messages from my institution regarding what TYPES OF ERRORS should be disclosed. | 2.92 | 1.07 | 0.87 | 0.79 | |

| Factor 3: Psychological barriers | 3.47 | 0.92 | 0.93 | |||

| 21. | Fear of disciplinary action | 3.44 | 1.07 | 0.55 | 0.93 | |

| 22. | Fear of losing patient trust | 3.95 | 1.07 | 0.61 | 0.93 | |

| 23. | Fear of losing colleague support | 3.36 | 1.20 | 0.68 | 0.92 | |

| 24. | Fear of personal failure | 3.63 | 1.17 | 0.84 | 0.92 | |

| 25. | Fear of losing self-esteem | 2.97 | 1.22 | 0.78 | 0.92 | |

| 26. | Fear of damaged reputation | 3.59 | 1.12 | 0.79 | 0.92 | |

| 27. | Fear of judgment from colleagues | 3.59 | 1.15 | 0.81 | 0.92 | |

| 30. | Fear of shame | 3.24 | 1.12 | 0.84 | 0.92 | |

| 31. | Fear that my peers will question my competence | 3.48 | 1.19 | 0.82 | 0.92 | |

| Factor 4: Financial Concern Barriers | 3.10 | 1.03 | 0.85 | |||

| 20. | Fear of litigation | 3.85 | 1.03 | 0.64 | 0.98 | |

| 28. | Fear of losing malpractice insurance coverage | 2.76 | 1.28 | 0.93 | 0.64 | |

| 29. | Fear of increased insurance premiums | 2.69 | 1.22 | 0.92 | 0.65 | |

| Other variables | 13. | I am uncertain about how to report errors and mistakes | 2.53 | 1.12 | ||

| 14. | My institution provides peer support services that help providers deal with the emotional consequences of error | 3.38 | 0.97 | |||

| 16. | I would like to be included in the error disclosure process in the event I am involved in a medical error | 1.85 | 0.74 | |||

| 17. | The physician is the ultimate one responsible for disclosing the medical error, regardless of his/her involvement in the error | 3.37 | 1.13 | |||

| 18. | I am afraid of being blamed for a medical error if I am not present during the disclosure conversation with a patient and/or patient’s family | 3.20 | 1.03 |

Intra-class correlations (ICCs) ranged from 0.35–0.70 indicating poor to good test-retest correspondence between continuous items in pilot draft. Two questions with ICCs <0.40 were deleted from the final BEDA tool resulting in a final version of 27 quantitative items.

Factor analysis revealed four factors for items 5–31: confidence and knowledge barriers, institutional barriers, psychological barriers, and financial concern barriers (Table 2). The factor loadings for each item of a given factor are reported in Table 2. Factor loadings allow for the assessment of how items are related to a factor. If an item has a loading over 0.4 on a factor, it is considered a good indicator of that factor.40 As can be observed, in all cases the factor loading associated with each item forming a factor is above 0.6, indicating that individual items are strongly correlated with a given factor or construct. Five items, questions 13, 15, 16, 17 and 18, did not load into any of the four factors and should be analyzed as single items.

In addition to analyzing factor loadings, we explored the internal consistency of items forming each intermediate variable. Table 2 reports the Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient for each item, assuming that all items are retained and the alpha coefficient that would be obtained if an item is dropped. Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient is the most commonly used measure of internal consistency of items in a model. It examines how well a set of items measures a single unidimensional factor. In general, an α > 0.70 is considered adequate reliability.41 As can be observed, the α coefficient for the confidence and knowledge barriers index is 0.86; if any of the items measuring confidence and knowledge barriers were dropped, a lower α coefficient would be obtained, indicating that all items should be kept as measures of confidence and knowledge barriers. The α coefficient associated with institutional barriers is 0.86; psychological barriers is 0.93, and financial concern barriers is 0.85.

The test-retest reliability of the tool was supported with alpha coefficients of 0.85–0.93 at time 1 and 0.82 – 0.95 at time 2 for the four factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results for Test and Re-test Reliability- Cronbach’s Alphas

| Factors | Test - Time 1 alphas | Retest - Time 2 alphas |

|---|---|---|

| Confidence and Knowledge barriers | 0.86 | 0.82 |

| Institutional barriers | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| Psychological barriers | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| Financial concern barriers | 0.85 | 0.95 |

Discussion

Health care providers’ disclosure of medical errors is an essential component of honest, transparent, and ethical communication between professional providers and the patients they serve. While this ideal is generally understood by those who provide patient care, real and concerning barriers to disclosure can inhibit full medical error disclosure by practitioners. Rankings of participant comfort and confidence with disclosing errors were low for these study participants with fear of losing patient trust and potential litigation as the highest rated barriers of concern, which is consistent with prior research.42 Identifying barriers to disclosure among health care providers in a systematic method can be the first step in addressing issues, such as the ones identified in this study, that impede the desired outcome of effective and full error disclosure.

The BEDA Tool shows promise as an instrument that can be used to identify and quantify barriers to disclosure, which can prohibit transparency and honesty in the provider-patient therapeutic relationship. The use of the Delphi process to create items for the BEDA tool contributed to the tool’s face and content validity. The four factor solution generated with factor analysis resulted in alpha coefficients that exceeded the 0.70 standard for each factor. Alpha coefficients above the 0.70 standard at times 1 and 2 provide evidence of acceptable test-retest reliability for the instrument.

Limitations

This study is limited to healthcare provider disclosure of medical errors to patients or their families, not barriers to internal and external event reporting. Barriers that are identified in the literature and that were included on the BEDA tool are primarily described from physician and nurse perspectives. Pharmacists were included as a healthcare provider population for validation of the BEDA tool. More research is needed regarding the similarities and differences inherent to error disclosure and potential barriers among these professional groups.

There is no consensus regarding what constitutes an optimal number of subjects in a Delphi study, however 10–15 subjects could be sufficient if the background of Delphi participants is homogeneous; conversely, a heterogeneous panel is typically larger in number.36 We utilized a heterogeneous panel in terms of professional backgrounds and perspectives of disclosure, because different points of view may enrich the results of the Delphi procedure and should be encouraged, depending on the study objective.37 Because our Delphi panel was heterogeneous, the study is limited by the relative small size of the panel, in which we risk not having a representative pooling of judgements regarding barriers to medical error disclosure. However, because barriers have already been extensively described in the literature and are not a new concept, a large panel composition was not considered critical. In addition, the drawbacks to a larger panel size are potentially lower response rates and the need for extended blocks of time for panelists to respond.

Utilizing the definition of a “modified” Delphi process given by Boulkedid et al., 37 our study design incorporated a physical meeting between rounds. Having a physical meeting is not consistent with the original and basic tenet of the Delphi procedure, because anonymity is not preserved and there is a risk of panel members dominating the consensus-building process. However, physical meetings are not uncommon and allow for face-to-face exchange of information and clarification when there are disagreements.37 We sought to balance this limitation by employing additional strategies for survey development, which included pre-testing the instrument, engaging in interactive interviews for question clarity, and pilot-testing the instrument by which to determine its psychometric properties.

Conclusion

The Barriers to Error Disclosure Assessment (BEDA) Tool was developed to identify and measure barriers to medical error disclosure among care providers to inform the development of a disclosure training program for healthcare professionals. A team of experts collaborated to develop an instrument that can be used to describe the beliefs and attitudes related to error disclosure in members of a variety of health care professions. With the identification and quantification of barriers to error disclosure, evidence-based interventions can be created and tested for effectiveness in reducing or eliminating the barriers among those who provide patient care. Evidence supporting the tool’s validity and reliability when describing barriers to medical error disclosures in physicians, pharmacists, and nurses indicates that the tool holds promise for future research and practice improvement in this clinical necessity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank and acknowledge L. Curtis Cary, Edward J. Dunn, Les Hall, Sara Kim, and James W. Pichert for their expert review and assistance in the development of the Barriers to Error Disclosure Assessment (BEDA) Tool. This pilot project was supported by the National Center for Research Resources at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1TR000117. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Appendix A. Draft-BARRIERS TO ERROR DISCLOSURE ASSESSMENT (BEDA) TOOL

| Instructions: Rate your agreement with the following statements regarding your attitudes toward disclosing a medical error to patients or their significant others. With this tool, medical error refers to an error made by any member of the healthcare team during patient care delivery. | |

| Item |

Rating 1 = strongly disagree 2 = disagree 3 = neutral 4 = agree 5 = strongly agree |

| I am confident in my ability to offer an effective apology in terms of disclosing a medical error to a patient. | |

| Fear of litigation affects my willingness to disclose a medical error to a patient. | |

| Fear of a disciplinary action affects my willingness to disclose a medical error. | |

| Fear of losing patient trust affects my willingness to disclose a medical error. | |

| Fear of losing colleague respect affects my willingness to disclose a medical error. | |

| Fear of losing colleague support affects my willingness to disclose a medical error. | |

| I am not sure how much I should disclose to a patient/family member in the event I am involved in a medical error. | |

| My employing institution supports disclosure of medical errors by health care providers. | |

| I receive mixed messages from my employing institution regarding the process of disclosing an error. | |

| I receive mixed messages from my employing institution regarding what types of errors should be disclosed. | |

| The physician should take full responsibility for the error, even when non-physician healthcare providers on the team may have played a role in the error (e.g. “I lead the team; this happened on my watch, therefore my fault.”) | |

| Non-physician healthcare providers do not have a role in disclosing medical errors, even when such providers on the team may have played a role in the error (i.e. only the physician should disclose the error). |

Appendix B. Final BEDA Tool

BARRIERS TO ERROR DISCLOSURE ASSESSMENT (BEDA) TOOL

This survey will collect data related to your current practice experience, degree of training related to medical error disclosure, and current comfort level in disclosing medical errors. This survey also asks questions to determine the degree to which known barriers may impact your ability or willingness to disclose medical errors to patients and/or their significant others. Data gathered from this survey will guide and inform the development of an error disclosure training curriculum. Data collected will provide a baseline by which to compare the outcome of the curriculum. Your responses are confidential. You may choose to skip any question you are not comfortable answering.

IMPORTANT NOTE

Please use the following definitions for the purposes of this survey:

Error Disclosure refers to communication between a health care provider and a patient, family members, or the patient’s proxy that acknowledges the occurrence of an error, discusses what happened, and describes the link between the error and outcomes in a manner that is meaningful to the patient.1

Medical error refers to error(s) made by any member of the healthcare team during patient care delivery and is defined by the Institute of Medicine as the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended (error of execution) or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim (error of planning). The subset of medical errors pertaining to this survey are those that result in patient harm.2

Patient harm is defined by the National Quality Forum as any unintended injury or impairment of the physical, emotional, or psychological function or structure of the body and/or pain resulting from or contributed to by medical care (including the absence of indicated medical treatment) that:3

Requires treatment or intervention

Requires initial or prolonged hospitalization

Requires life-sustaining intervention

Results in temporary or permanent disability

Results in death

-

Have you received any level of training in medical error disclosure?

Yes

No

-

What specific aspects regarding medical error disclosure would be helpful for you to learn more about? (Check yes or no for each item)

Yes No Improvisational methods of communication (i.e. how to disclose an error, what to say) Empathic communication skills (how to say it) How to apologize Disclosure as an interprofessional team Other (please specify) -

Have you ever personally disclosed a medical error to a patient, patient’s family, or patient’s significant other?

Yes

No

-

Have you ever disclosed a medical error with a team of other healthcare professionals?

Yes

No

Instructions

The following statements are related to different aspects of error disclosure. Indicate your degree of agreement with the following statements.

| Statement | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. I am comfortable in my ability to disclose a medical error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 6. I am confident in my ability to disclose a medical error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 7. I am not sure how much I should disclose to a patient/family member in the event I am involved in a medical error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 8. My institution supports an atmosphere of transparency in error disclosure. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 9. My institution supports disclosure of medical errors by health care providers. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 10. I receive mixed messages from my institution regarding the process of disclosing an error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 11. I receive mixed messages from my institution regarding what types of errors should be disclosed. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 12. I am not sure when I should disclose an error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 13. I am uncertain about how to report errors/mistakes. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 14. My institution provides peer support services that help providers deal with the emotional consequences of error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 15. I am unsure of my role in a disclosure conversation with the patient and/or family members. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 16. I would like to be included in the error disclosure process in the event I am involved in a medical error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 17. The physician is the ultimate one responsible for disclosing the medical error, regardless of his/her involvement in the error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 18. I am afraid of being blamed for a medical error if I am not present during the disclosure conversation with a patient and/or patient’s family. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 19. Other non-physician healthcare providers (e.g. nurses, pharmacists, etc.) should be included in the disclosure conversation if they contributed to the occurrence of the error. | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

The following are known barriers within the literature that impact providers’ ability or willingness to disclose a medical error. To what degree do the following pose a barrier in your ability or willingness to disclose an error?

| Barrier | Very much a barrier | Somewhat of a barrier | Neutral | Not much of a barrier | Not at all a barrier |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20. Fear of litigation | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 21. Fear of disciplinary action | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 22. Fear of losing patient trust | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 23. Fear of losing colleague support | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 24. Fear of personal failure | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 25. Fear of losing self-esteem | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 26. Fear of damaged reputation | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 27. Fear of judgment from colleagues | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 28. Fear of losing malpractice insurance coverage | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 29. Fear of increased insurance premiums | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 30. Fear of shame | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 31. Fear that peers will question my competence | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Contributor Information

Darlene Welsh, University of Kentucky, College of Nursing, 427 College of Nursing Building, Lexington, Kentucky 40536-0232.

Dominique Zephyr, University of Kentucky, Applied Statistics Laboratory.

Andrea L. Pfeifle, Indiana University, School of Medicine, Assistant Dean and Director, Center for Interprofessional Health Education and Practice.

Douglas E. Carr, Indiana University School of Medicine, Division of General Surgery.

Joseph L. Fink, III, University of Kentucky, College of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science.

Mandy Jones, University of Kentucky, College of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science.

References

- 1.James JT. A new, evidence-based estimate of patient harms associated with hospital care. J Patient Saf. 2013;9(3):122–128. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182948a69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Quality Forum (NQF) Safe practices for better healthcare-2010 update: A consensus report. Washington, DC: NQF; 2010. [Accessed 6/28/16]. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2010/04/Safe_Practices_for_Better_Healthcare_%E2%80%93_2010_Update.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Commission, TJ. Hospital Accreditation Standards, 2007. Oakbrook Terrace, Il: Joint Commission Resources; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine (IOM) To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher TH, Waterman AD, Ebers AG, et al. Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289:1001–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iedema R, Sorensen R, Manias E, et al. Patients’ and family members’ experiences of open disclosure following adverse events. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2008;20(6):421–432. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzn043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American College of Healthcare Executives (ACHE) [Accessed 6/28/16];ACHE Code of Ethics. 2011 https://www.ache.org/abt_ache/code.cfm.

- 8.American Medical Association (AMA) [Accessed 6/28/16];Code of medical ethics. 2001 Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics.page.

- 9.American Nurses Association (ANA) [Accessed 6/28/16];Code of ethics for nurses with interpretive statements. 2015 Available at http://www.nursingworld.org/codeofethics.

- 10.Fein SP, Hilborne LH, Spiritus EM, et al. The many faces of error disclosure: A common set of elements and a definition. JGIM. 2007;22:755–761. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannawa AF, Beckman H, Mazor KM, et al. Building bridges: future directions for medical error disclosure research. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etchegaray JM, Gallagher TH, Bell SK, Dunlap B, Thomas EJ. Error disclosure: A new domain for safety culture assessment. Brit Med J Qual Saf. 2012;21:594–599. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Leapfrog Group. [Last accessed June 29, 2016];Leapfrog Hospital Survey Hard Copy. 2016 Version 6.3, Updated June 24, 2016. Available at http://www.leapfroggroup.org/sites/default/files/Files/2016Survey_Final_Updated06242016.pdf.

- 14.Wolf ZR, Hughes RG. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Apr, 2008. Chapter 35: Error Reporting and Disclosure. AHRQ Publication No. 08-0043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallagher TH. Using simulation to enhance team communication and error disclosure to patients. [Accessed April 17, 2015];Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality web site. 2008 Sep 8; Available at: www.archive.ahrq.gov/news/events/conference/2008/Gallagher.html.

- 16.Rosner F, Berger JT, Kark P, et al. Disclosure and prevention of medical errors. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2089–2092. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, et al. Physician-patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:553–560. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincent C, Young M, Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Lancet. 1994;343:1609–13. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etchegaray JM, Ottosen MJ, Burress L, et al. Structuring patient and family involvement in medical error event disclosure and analysis. Health Affairs. 2014;33:46–52. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waterman AD, Garbutt J, Hazel E, Dunagan WC, Levinson W, Fraser VJ, Gallagher TH. The emotional impact of medical errors on practicing physicians in the US and Canada. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2007;33(8):467–476. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hannawa AF. Disclosing medical errors to patients: Effects of nonverbal involvement. Patient Education and Counseling. 2014;94(3):310–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakefield DS, Wakefield BJ, Uden-Holman T, et al. Perceived barriers in reporting medications administration errors. Best Pract Benchmarking Health. 1996;1(4):191–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blegen MA, Vaughn T, Pepper G, et al. Patient and staff safety: voluntary reporting. Amer J Med Qual. 2004;19(2):67–74. doi: 10.1177/106286060401900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaldjian LC, Jones EW, Rosenthal GE, et al. An empirically derived taxonomy of factors affecting physicians’ willingness to disclose medical errors. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:942–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapp MB. Medical error versus malpractice. DePaul J Health Care Law. 1997;1:750–72. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uribe CL, Schweikhart SB, Pathak DS, et al. Perceived barriers to medical-error reporting: an exploratory investigation. J Health Care Manag. 2002;47(4):263–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halbach JL, Sullivan LL. Teaching medical students about medical errors and patient safety: evaluation of a required curriculum. Acad Med. 2005;80:600–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200506000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillies RA, Speers SH, Young SE, et al. Teaching medical error apologies: development of a multi-component intervention. Fam Med. 2011;43:400–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wayman KI, Yaeger KA, Sharek PJ, et al. Simulation-based medical error training for pediatric healthcare professionals. Journal for Healthcare Quality. 2007;29:12–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2007.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? JAMA. 2004;291:1246–1251. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine (IOM) Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leape L, Berwick D, Clancy C, et al. Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2009;18:424–8. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.036954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner EH. The role of patient care teams in chronic disease management. BMJ. 2000;320:569–572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7234.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: The chronic care model, part 2. JAMA. 2002;288:1909–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Affairs. 2001;20:64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hsu C, Sandford BA. The Delphi Technique: Making sense of consensus. [Accessed June 19, 2015];Practical Assessment & Evaluation. 2007 12(10) http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=12&n=10. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, et al. Using and reporting the Delphi Method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shoukri MM, Asyali MH, Donner A. Sample size requirements for the design of reliability study: Review and new results. Stat Methods Med Res. 2004;13:251–271. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fleiss J. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Acock AC. A Gentle Introduction to Stata. 3. College Station, Texas: Stata Press; 2010. Measurement, Reliability, and Validity. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. 2. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez B, Knych SA, Weaver SJ, et al. Understanding the barriers to physician error reporting and disclosure: A systematic approach to a systemic problem. J Patient Saf. 2014;10(1):45–51. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0b013e31829e4b68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]