Abstract

Objective

To conduct systematic analyses to evaluate the efficacy of progesterone therapy for the prevention of miscarriages in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion.

Methods

In November 2016, we performed a systematic literature search and identified 51 articles in PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases. We identified nine randomized trials that included 913 pregnant women (including 322 treated with oral dydrogesterone, 213 treated with vaginal progesterone, and 378 control subjects) who met the selection criteria.

Results

The incidence of miscarriage was significantly lower in the total progesterone group than in the control group (13.0% versus 21.7%; odds ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.36 to 0.78; P = 0.001; I2, 0%). Moreover, the incidence of miscarriage was significantly lower in the oral dydrogesterone group than in the control group (11.7% versus 22.6%; odds ratio, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.26 to 0.71; P = 0.001; I2, 0%) and was lower in the vaginal progesterone group than in the control group, although this difference was nonsignificant (15.4% versus 20.3%; odds ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.34; P = 0.30; I2, 0%). However, the incidence of miscarriage was not different between the oral dydrogesterone and vaginal progesterone groups.

Conclusion

Progesterone therapy, especially oral dydrogesterone, can effectively prevent miscarriage in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion.

1. Introduction

Progesterone maintains pregnancy by enhancing uterine quiescence [1]. During early pregnancy, the syncytiotrophoblast secretes human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which stimulates progesterone production in the corpus luteum by preventing regression of this tissue [2]. After seven to nine weeks of gestation, progesterone is directly secreted by the syncytiotrophoblast [2, 3]. Low serum hCG or progesterone levels may predict first trimester abortions [4]. During early pregnancy in women with threatened abortion, progesterone levels were lower in those who had a subsequent miscarriage than in those whose pregnancies continued to fetal viability [5]. Moreover, progesterone receptor antagonists may induce abortion or labor by increasing myometrial contractility and excitability throughout pregnancy [1, 6].

Threatened abortion, which occurs in 20% of all pregnancies, is diagnosed when vaginal bleeding with or without abdominal pain occurs during the first half of pregnancy. The required prerequisites for threatened abortion are a closed cervix and an intrauterine viable fetus [7, 8]. Unfortunately, nearly half of threatened abortions end in miscarriage [7, 8]. Progesterone has been used to treat threatened abortions, but its efficacy remains unclear [8–17].

Previous meta-analyses have shown that progesterone therapy may reduce the risk of miscarriage in pregnant women with threatened abortion. However, these meta-analyses were limited by a small number of included studies [8, 9]. Furthermore, these systematic analyses only included randomized studies that demonstrated the efficacy of the oral progesterone dydrogesterone, a pure progestin that was developed in the 1950s [8, 9, 18], and revealed that vaginal progesterone was ineffective [8, 9].

Although many studies have evaluated the impact of progesterone as a treatment for threatened abortion, only a few randomized studies have been conducted to explore this issue. Recently, some additional randomized studies reported the effect of progesterone therapy in pregnant women with threatened abortion. In this study, using an updated systematic analysis, we aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of progesterone therapy delivered via different administration routes for preventing miscarriages in pregnant women with threatened abortion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Methods

In November 2016, we searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases for all relevant studies without limiting the publication year. A combination of the following terms using Boolean operators was used to perform the search: [(threatened abortion OR miscarriage) AND (progesterone OR progestin) AND randomized trial] and [(threatened abortion OR miscarriage) AND (dydrogesterone OR duphaston)]. Additional relevant studies that were not identified by the database searches were identified by examining the references of the selected clinical studies and review articles.

2.2. Selection Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used for study selection: studies of pregnant women diagnosed with threatened abortion before 20 weeks of gestation, studies that compared any type of progesterone therapy with either placebo or conservative treatment, studies that compared different administration routes of progesterone therapy, studies that reported the incidence of miscarriage, and randomized or quasi-randomized controlled studies. The exclusion criteria were as follows: studies that were not case-match controlled, noncomparative studies, studies not in English, review articles, editorials, letters, case reports, in vitro research studies, and studies using other therapeutic agents. To avoid including duplicate information, when multiple studies were found to have included overlapping groups of patients, only the study with the largest number of events was included in the meta-analysis. Some results were published only in abstract form and not in full, and we found that some clinically useful evidence could be extracted from these studies.

2.3. Data Extraction and Outcomes of Interest

Two investigators developed a checklist for data recording, and they independently extracted the data of interest from the studies. If there was any disagreement between the findings of these investigators, they were resolved by discussion. The eligible population was classified into the following three groups: patients administered oral dydrogesterone therapy, patients administered vaginal progesterone therapy, and a control group that was administered placebo or conservative treatment. The following data were retrieved from the studies: the name of the first author, publication year, study design, eligibility criteria, sample size, interventions, and incidence of miscarriage. The incidence of miscarriage was the principal outcome of the meta-analysis and was compared among the treatment groups.

2.4. Overall Quality of the Body of Evidence

The quality of the evidence for the principle outcomes was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) working group recommendations [21] as follows: the limitation (e.g., risk of bias) of the included studies, inconsistency of the observed effects, indirectness, imprecision, and risk of publication bias. The quality of the evidence was reported as follows: high quality, which indicates that further research is highly unlikely to change the confidence in the estimate of effect; moderate quality, which indicates that further research is likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; low quality, which indicates that further research is highly likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; very low quality, which indicates that we are highly uncertain about the estimate.

2.5. Publication Bias and Statistical Analyses

To analyze the outcomes, a random-effects model was implemented using the Mantel-Haenszel method. The heterogeneity of the odds ratios (ORs) was assessed using the I2 statistic, and publication bias was identified using funnel plots. To generate a scatter plot, the horizontal axis was plotted as the OR of each study, and the vertical axis was plotted as the corresponding standard error of the log of the OR. Review Manager Version 5.3 software (The Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used for the meta-analysis. GRADE evidence profiles were created using GRADEpro GDT. A P value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. Subgroup analyses of the risk of miscarriage according to eligibility criteria, vaginal progesterone dose, and quality of studies were performed; however, a subgroup analysis based on oral dydrogesterone was not performed because similar doses were used in the studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies (n = 9).

| Study | Year | Study design | Eligibility criteria | Sample size | Interventions |

|

| |||||

| Alimohamadi et al. [11]. | 2013 | Randomized (double-blind) |

Vaginal bleeding and uterine cramps before the 20th week of pregnancy, live singleton by ultrasound | 71 71 |

Vaginal progesterone: 200 mg, twice a day for 1 week Control: placebo using the same method |

|

| |||||

| Czajkowski et al. [19]. | 2007 | Randomized (double-blind) |

Vaginal bleeding usually accompanied by abdominal pain before 12 weeks of pregnancy, live singleton by ultrasound | 29 24 |

Vaginal progesterone: micronized, 300 mg, once per day for 6 weeksa Oral dydrogesterone: 30 mg using the same method |

|

| |||||

| El-Zibdeh and Yousef [12]. | 2009 | Quasi-randomized (open-label) |

Mild or moderate vaginal bleeding during the first trimester of pregnancy, live embryo by ultrasound | 86 60 |

Oral dydrogesterone: 10 mg, twice per day until 1 week after bleeding had stopped Control: conservative treatment |

|

| |||||

| Gerhard et al. [13]. | 1987 | Randomized (double-blind) | Vaginal bleeding during the first trimester of pregnancy, live singleton by ultrasound | 17 17 |

Vaginal progesterone: 25 mg, twice per day for 14 days after bleeding had stopped Control: placebo using the same method |

|

| |||||

| Hui et al. [20].b | 2015 | Randomized | Vaginal bleeding between weeks 6 and 10 of pregnancy | 41 42 |

Vaginal progesterone: micronized Oral dydrogesterone |

|

| |||||

| Omar et al. [14]. | 2005 | Randomized (open-label) | Mild or moderate vaginal bleeding before 13 weeks of pregnancy, live embryo by ultrasound | 74 80 |

Oral dydrogesterone: initial: 40 mg; maintenance: 10 mg, twice per day until bleeding had stopped or for 1 weekc Control: conservative treatment |

|

| |||||

| Pandian [15]. | 2009 | Randomized (open-label) | Vaginal bleeding up to the 16th week of pregnancy, live embryo by ultrasound | 96 95 |

Oral dydrogesterone: initial: 40 mg; maintenance: 10 mg, twice per day until the 16th week of pregnancy Control: conservative treatment |

|

| |||||

| Palagiano et al. [16]. | 2004 | Randomized (double-blind) |

Vaginal bleeding and uterine cramps between weeks 6 and 12 of pregnancy with a previous diagnosis of inadequate luteal phase, live embryo by ultrasound | 25 25 |

Vaginal progesterone: micronized, 90 mg, once per day for 5 daysd Control: placebo using the same method |

|

| |||||

| Yassaee et al. [17]. | 2014 | Randomized (single-blind) |

Vaginal bleeding until the 20th week of pregnancy, live singleton by ultrasound | 30 30 |

Vaginal progesterone: micronized, 400 mg, once per day until bleeding stopped within less than 1 week Control: conservative treatmente |

aAdamed Inc., Poland; blimited information was available because the study was published only in abstract form; cunclear data regarding the duration of treatment; dCrinone 8%® (progesterone gel, Merck Serono Inc., Germany); eCyclogest® (Actavis Inc., UK).

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Characteristics and Assessments of the Risk of Bias in the Included Studies

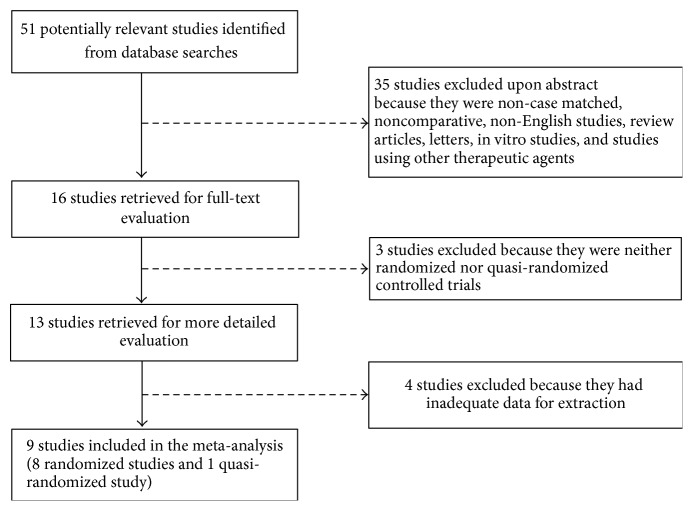

Our literature search initially identified 51 potentially relevant studies; 8 randomized controlled studies and 1 quasi-randomized study that met the selection criteria were ultimately identified (Figure 1). The characteristics of the included studies are provided in Table 1, and assessments of the risk of bias in each study are provided in Table 2. Alimohamadi et al. [11] and Gerhard et al. [13] did not include information regarding the type (natural or synthetic) of vaginal progesterone that was administered. The study by Hui et al. [20] was only published in abstract form and did not provide information regarding the method for confirming live embryos or the dosages and duration of treatment with progestational agents. The included studies had a total of 913 pregnant women (including 322 treated with oral dydrogesterone, 213 treated with vaginal progesterone, and 378 control subjects) (Tables 1 and 3; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the procedure used for study selection.

Table 2.

Assessments of the risk of bias in the included studies.

| Study | Random sequence generation (selection bias) |

Allocation concealment (selection bias) |

Blinding of the participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) |

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting (reporting bias) |

Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alimohamadi et al. [11]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Support for judgement | Adequate method for randomization | Adequate allocation concealment | Blinding of the participants and personnel | No information for blinding of outcome assessors | No incomplete outcome data | Report of all outcomes | No intention to treat analysis |

|

| |||||||

| Czajkowski et al. [19]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | High risk |

| Support for judgement | No information regarding the method used for randomization | No mention for the method of allocation concealment | Blinding of the participants and personnel | No information for blinding of outcome assessors | No information for the number of participants who were lost for follow-up according to subgroups | Report of all outcomes | No intention to treat analysis |

|

| |||||||

| El-Zibdeh and Yousef [12]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Support for judgement | Quasi-randomized participants based on which day of the week the pregnant women came to the clinic | No allocation concealment | Neither blinding of the participants nor personnel | Adequate blinding for outcome assessors | No incomplete outcome data, analysis in all participants enrolled | Report of all outcomes | No intention to treat analysis for some variables |

|

| |||||||

| Gerhard et al. [13]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | High risk |

| Support for judgement | No information regarding the method used for randomization | No mention for the method of allocation concealment | Blinding of the participants and personnel | No information for blinding of outcome assessors | No information for the number of participants who were lost for follow-up according to subgroups | Report of all outcomes | No intention to treat analysis |

|

| |||||||

| Hui et al. [20]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Support for judgement | No information regarding the method used for randomization | No mention for the method of allocation concealment | No information | No information | No information | No information | No information |

|

| |||||||

| Omar et al. [14]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | High risk |

| Support for judgement | No information regarding the method used for randomization | No mention for the method of allocation concealment | Neither blinding of the participants nor personnel | No information for blinding of outcome assessors | No information for the number of participants who were lost for follow-up according to subgroups | Report of all outcomes | No intention to treat analysis |

|

| |||||||

| Pandian [15]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Support for judgement | Adequate method for randomization | Adequate allocation concealment | Neither blinding of the participants nor personnel | Unclear information for blinding of outcome assessors | No incomplete outcome data, analysis in all participants enrolled | Report of all outcomes | No additional bias |

|

| |||||||

| Palagiano et al. [16]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear | Unclear | Low risk | High risk |

| Support for judgement | No information regarding the method used for randomization | Adequate allocation concealment | Blinding of the participants and personnel | No information for blinding of outcome assessors | No information for the number of participants who were lost for follow-up | Report of all outcomes | No intention to treat analysis |

|

| |||||||

| Yassaee et al. [17]. | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Authors' judgement | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Support for judgement | No information regarding the method used for randomization | No mention for the method of allocation concealment | No blinding of the participants | No information for blinding of outcome assessors | No incomplete outcome data, analysis in all participants enrolled | Report of all outcomes | No additional bias |

Table 3.

GRADE evidence profiles: risk of miscarriage in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion based on the route of progesterone administration.

(a) Progesterone agents versus control treatments

| Quality assessment | Number of patients (%) | Absolute effect (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Progesterone agents | Control | Progesterone agents | Control | |||

| Outcome: miscarriage | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Progesterone versus control | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 7 | Randomized trials | Seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousb | None | 52/399 (13.0) | 82/378 (21.7) | 128 per 1000 | 217 per 1000 | OR 0.53 (0.36 to 0.78) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

|

89 fewer per 1,000 (from 39 fewer to 126 fewer) | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Oral dydrogesterone versus control | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials | Seriousa | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousb | None | 30/256 (11.7) | 53/235 (22.6) | 112 per 1000 | 226 per 1000 | OR 0.43 (0.26 to 0.71) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| 114 fewer per 1,000 (from 54 fewer to 155 fewer) | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Vaginal progesterone versus control | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomized trials | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | 22/143 (15.4) | 29/143 (20.3) | 155 per 1000 | 203 per 1000 | OR 0.72 (0.39 to 1.34) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | Critical |

| 48 fewer per 1,000 (from 51 more to 113 fewer) | |||||||||||||

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; aeither the participants or personnel were not blinded in these studies (performance bias); bthe 95% CI includes appreciable harm or benefit.

(b) Oral dydrogesterone versus vaginal progesterone

| Quality assessment | Number of patients (%) | Absolute effect (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Oral dydrogesterone | Vaginal progesterone | Oral dydrogesterone | Vaginal progesterone | |||

| Outcome: miscarriage | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 2 | Randomized trials | Seriousc | Not serious | Not serious | Seriousc | None | 12/70 (17.1) | 11/66 (16.7) | 175 per 1000 | 167 per 1000 | OR 1.06 (0.42 to 2.66) | ⨁⨁◯◯ Low | Critical |

| 8 more per 1,000 (from 89 fewer to 181 more) | |||||||||||||

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; climited information was available because a study was only published in abstract form.

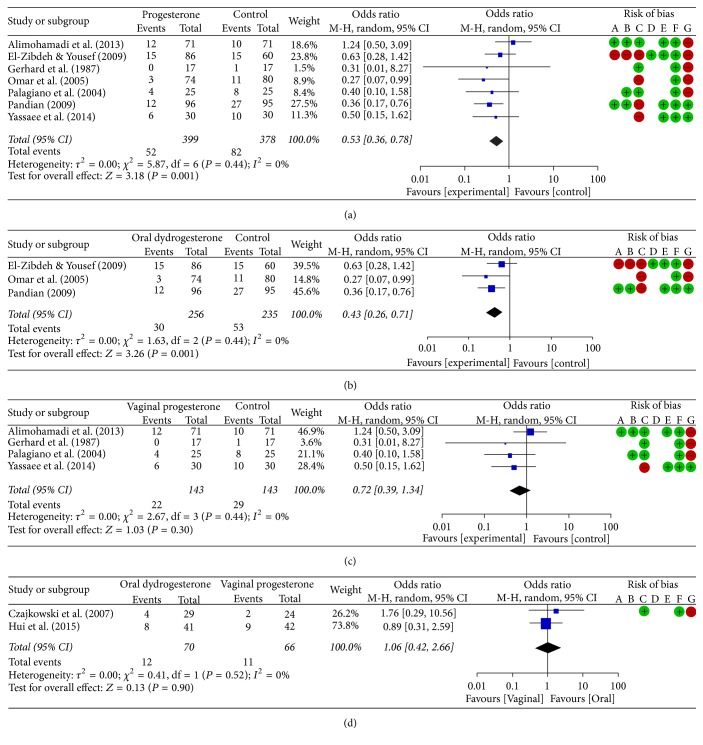

Figure 2.

Forest plots and risk of bias: risk of miscarriage in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion based on the route of progesterone administration. (a) Total progesterone versus control treatments. (b) Oral dydrogesterone versus control treatments. (c) Vaginal progesterone versus control treatments. (d) Oral dydrogesterone versus vaginal progesterone treatments. The risk of bias for each metric was assessed as low (+), high (−), or unclear (blank) for all the included studies as follows: A, random sequence generation (selection bias); B, allocation concealment (selection bias); C, blinding of the participants and personnel (performance bias); D, blinding of the outcome assessment (detection bias); E, incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); F, selective reporting (reporting bias); G, other bias. M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; CI, confidence interval.

3.2. Risk of Miscarriage Based on the Route of Progesterone Administration in Pregnant Women Experiencing Threatened Abortion

The incidence of miscarriage was significantly lower in the total progesterone group than in the control group (13.0% versus 21.7%; odds ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.36 to 0.78; P = 0.001; I2, 0%; 7 RCTs, 777 pregnant women; low quality evidence; Table 3(a), Figure 2(a), and Supplementary Figure 1(a)). Moreover, the incidence of miscarriage was significantly lower in the oral dydrogesterone group than in the control group (11.7% versus 22.6%; odds ratio, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.26 to 0.71; P = 0.001; I2, 0%; 3 RCTs, 491 pregnant women; low quality evidence; Table 3(a), Figure 2(b), and Supplementary Figure 1(b)) and was lower in the vaginal progesterone group than in the control group; however, this difference was not significant (15.4% versus 20.3%; odds ratio, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.39 to 1.34; P = 0.30; I2, 0%; 4 RCTs, 286 pregnant women; high quality evidence; Table 3(a), Figure 2(c), and Supplementary Figure 1(c)). However, the incidence of miscarriage was not different between the oral dydrogesterone and vaginal progesterone groups (17.1% versus 16.7%; odds ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.42 to 2.66; P = 0.90; I2, 0%; 2 RCTs, 136 pregnant women; low quality evidence; Table 3(b), Figure 2(d), and Supplementary Figure 1(d)).

3.3. Subgroup Analyses

When comparing the subgroups based on eligibility criteria, the incidence of miscarriage among patients experiencing threatened abortion within 12 completed weeks of gestation was significantly lower in the total progesterone group than in the control group (P = 0.01). In patients experiencing threatened abortion before 20 weeks of gestation, the incidence of miscarriage was also lower in the total progesterone group than in the control group, although this difference was not significant (P = 0.20). When comparing the subgroups according to the vaginal progesterone dose (400 mg or less than 400 mg) because of the large discrepancy between the doses, high doses of progesterone were not associated with the incidence of miscarriage between the groups (P = 0.72). However, among the groups treated with a lower dose of hormone, the incidence of miscarriage was lower in the progesterone group than in the control group, although this difference was not significant (P = 0.14; Table 4 and Supplementary Figure 2).

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses of risk of miscarriage according to eligibility criteria and vaginal progesterone dose.

| Subgroups | Studies, n | Number of patients (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity (I2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | Control | |||||

| Eligibility criteria | ||||||

| Threatened abortion within 12 completed weeks of gestation | 4 (12,13,14,16) | 22/202 (10.9) | 35/182 (19.2) | 0.47 (0.26–0.86) | 0.01 | 0% |

| Threatened abortion before 20 weeks of gestation | 3 (11,15,17) | 30/197 (15.2) | 47/196 (24.0) | 0.60 (0.27–1.31) | 0.20 | 53% |

| Vaginal progesterone dose | ||||||

| Higha | 2 (11,17) | 18/101 (17.8) | 20/101 (19.8) | 0.85 (0.35–2.05) | 0.72 | 30% |

| Lowb | 2 (13,16) | 4/42 (9.5) | 9/42 (21.4) | 0.39 (0.11–1.37) | 0.14 | 0% |

aHigh-dose use of vaginal progesterone included studies that administered 400 mg per day for 1 week or until bleeding stopped within less than 1 week. bLow-dose use of vaginal progesterone included studies using a dose lower than the reported high dose.

4. Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we demonstrated that progesterone therapy may be effective in preventing miscarriages in pregnant women with threatened abortion. In particular, oral dydrogesterone prevented miscarriage in pregnant women more effectively than the control-treated groups (placebo or conservative treatment), although there was no difference between oral and vaginal progestational agents in preventing miscarriages in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion.

The route of administration may influence the efficacy of progesterone therapy during pregnancy [22, 23]. Vaginal progesterone administration resulted in higher endometrial progesterone concentrations than those observed in patients administered oral and intramuscular progesterone [23]. Oral and vaginal administration routes are noninvasive, whereas intramuscular administration is invasive. Additionally, the oral and vaginal routes of administration are associated with acceptable and minimal side effects, respectively, whereas side effects were reported in one-third of pregnant women who received weekly intramuscular injections of progesterone to prevent recurrent preterm delivery [22–24]. Oral synthetic progestational agents, including dydrogesterone, have been developed to eliminate issues related to the variable bioavailability of natural formulations of oral progesterone [23]. A randomized study reported that micronized vaginal progesterone, but not oral dydrogesterone, decreased spiral artery pulsatility and the resistance index in the uteroplacental circulation of early pregnancies with threatened abortion [19].

In previous meta-analyses that included only randomized studies, vaginal and intramuscular progesterone administration effectively reduced the risk of preterm birth without any deleterious effects on fetal development [25, 26]. In a randomized study, a lower risk of preterm birth was associated with oral micronized progesterone than placebo [27]. Additionally, in a recent meta-analysis, oral dydrogesterone was as effective as vaginal progesterone for luteal phase support in assisted reproduction [28]. It has also been reported that intramuscular progesterone administration is associated with implantation, clinical pregnancy, and delivery rates that are comparable to those resulting from treatment with vaginal progesterone during stimulated IVF cycles [29]. These previous studies demonstrated that various progestational agents may induce similar outcomes despite the fact that differences in their efficacy were associated with the route of administration. In support of these studies, our meta-analysis showed that there was no difference in the rate of miscarriages between pregnant women with threatened abortion who were administered oral or vaginal progestational agents, although the small numbers of pregnant women and studies that were included limit the significance of these results.

Many studies have supported the efficacy of vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm births and luteal phase defects [25, 26, 28, 29]. Therefore, it is possible that miscarriages in pregnant women with threatened abortion might also be prevented by vaginal progesterone. However, a previous meta-analysis that included a small number of randomized studies showed that oral dydrogesterone, but not vaginal progesterone, reduced the incidence of miscarriage in pregnant women with threatened abortion [9]. Although we included a few additional recently reported randomized studies in our meta-analysis, the number of studies analyzed remained small. Our study also failed to show that vaginal progesterone was more effective in preventing miscarriages in pregnant women with threatened abortion than that in the controls, although we did find that oral dydrogesterone was effective. However, based on the subgroup analyses, our study showed that progesterone therapy was effective in preventing miscarriage—especially in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy. This meta-analysis clearly showed the effectiveness of progesterone therapy for the prevention of miscarriage. These findings indicate that well-designed and large-scale studies are necessary to further demonstrate impact of progesterone therapy.

Our meta-analysis had several limitations. First, only studies that were either randomized or quasi-randomized and evaluated either oral dydrogesterone or vaginal progesterone administration were included in this analysis. Unfortunately, there were neither randomized nor quasi-randomized trials that evaluated the efficacy of intramuscular progesterone administration or oral formulations of progestins other than dydrogesterone in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion. Second, because there is a paucity of studies that provided adequate data, we included small-scale studies as well as those with poor methodological quality in our analysis. Third, in the analyses comparing efficacy between oral progesterone and control treatments, between vaginal progesterone and control treatments, and between oral and vaginal progesterone, only a few eligible studies that included a small cohort of pregnant women could be analyzed. Finally, our searches were limited to the studies published in English. We found 2 studies not written in English that met our eligibility criteria. However, the significance of those studies was limited based on the publication year (1967) and lack of accessibility (no available abstract in English and difficulty finding experts in the relevant languages).

In conclusion, based on our systematic review and meta-analysis, we suggest that progesterone therapy, especially oral dydrogesterone, may effectively prevent miscarriages in pregnant women with threatened abortion. Although the number, scale, and methodological quality of the eligible studies limit the significance of our meta-analysis results, these results are important because we systemically analyzed all currently available randomized studies. Large-scale, multicenter, randomized and controlled studies are needed to better evaluate the efficacy of progesterone therapy in pregnant women with threatened abortion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

All authors participated in designing the research. Hee Joong Lee and Banghyun Lee searched the studies, extracted the data of interest, and performed the data analysis. Hee Joong Lee drafted the manuscript, and all other authors commented on it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Funnel plots: risk of miscarriage in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion based on the route of progesterone administration.

Supplementary Figure 2: Funnel plots: subgroup analyses of risk of miscarriage according to eligibility criteria, vaginal progesterone dose, and the study quality.

References

- 1.Mesiano S., Wang Y., Norwitz E. R. Progesterone receptors in the human pregnancy uterus: do they hold the key to birth timing? Reproductive Sciences. 2011;18(1):6–19. doi: 10.1177/1933719110382922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakajima S. T., Nason F. G., Badger G. J., Gibson M. Progesterone production in early pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 1991;55(3):516–521. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)54178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi C. Z., Zhang Z. Y., Zhuang L. Z. Study on reproductive endocrinology of human placenta (III)–Hormonal regulation of progesterone production by trophoblast tissue of first trimester. Science in China. Series B: Chemistry, Life Sciences and Earth Sciences. 1991;34(9):1098–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osmanağaoğlu M. A., Erdoğan I., Eminağaoğlu S., et al. The diagnostic value of β-human chorionic gonadotropin, progesterone, CA125 in the prediction of abortions. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2010;30(3):288–293. doi: 10.3109/01443611003605286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al‐Sebai M. A. H., Kingsland C. R., Diver M., Hipkin L., McFadyen I. R. The role of a single progesterone measurement in the diagnosis of early pregnancy failure and the prognosis of fetal viability. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1995;102(5):364–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb11286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norwitz E. R., Caughey A. B. Progesterone supplementation and the prevention of preterm birth. Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;4(2):60–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everett C. Incidence and outcome of bleeding before the 20th week of pregnancy: Prospective study from general practice. British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7099):32–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7099.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carp H. A systematic review of dydrogesterone for the treatment of recurrent miscarriage. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2015;31(6):422–430. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2015.1006618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahabi H. A., Fayed A. A., Esmaeil S. A., Al Zeidan R. A. Progestogen for treating threatened miscarriag. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011;12:p. Cd005943. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005943.pub4.005943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalinka J., Szekeres-Bartho J. The impact of dydrogesterone supplementation on hormonal profile and progesterone-induced blocking factor concentrations in women with threatened abortion. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2005;53(4):166–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alimohamadi S., Javadian P., Gharedaghi M. H., et al. Progesterone and threatened abortion: A randomized clinical trial on endocervical cytokine concentrations. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2013;98(1-2):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Zibdeh M. Y., Yousef L. T. Dydrogesterone support in threatened miscarriage. Maturitas. 2009;65(1):S43–S46. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerhard I., Gwinner B., Eggert-Kruse W., Runnebaum B. Double-blind controlled trial of progesterone substitution in threatened abortion. Biological Research in Pregnancy and Perinatology. 1987;8(1):26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omar M. H., Mashita M. K., Lim P. S., Jamil M. A. Dydrogesterone in threatened abortion: Pregnancy outcome. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2005;97(5):421–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandian R. U. Dydrogesterone in threatened miscarriage: A Malaysian experience. Maturitas. 2009;65(1):S47–S50. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palagiano A., Bulletti C., Pace M. C., De Ziegler D., Cicinelli E., Izzo A. Effects of vaginal progesterone on pain and uterine contractility in patients with threatened abortion before twelve weeks of pregnancy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1034:200–210. doi: 10.1196/annals.1335.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yassaee F., Shekarriz-Foumani R., Afsari S., Fallahian M. The effect of progesterone suppositories on threatened abortion: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Reproduction and Infertility. 2014;15(3):147–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reerink E. H., Schöler H. F. L., Westerhof P., et al. A new class of Hormonally active steroids. Nature. 1960;186(4719):168–169. doi: 10.1038/186168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Czajkowski K., Sienko J., Mogilinski M., Bros M., Szczecina R., Czajkowska A. Uteroplacental circulation in early pregnancy complicated by threatened abortion supplemented with vaginal micronized progesterone or oral dydrogesterone. Fertility and Sterility. 2007;87(3):613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.07.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui C. Y. Y., Siew S. J. Y., Tan T. C. Biochemical and clinical outcomes following the use of micronised progesterone and dydrogesterone for threatened miscarriage-a randomised controlled trial [abstract EP13.55] BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2015;122:p. 276. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyatt G., Oxman A. D., Akl E. A., et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings table. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(4):383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucovnik M., Kuon R. J., Chambliss L. R., et al. Progestin treatment for the prevention of preterm birth. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2011;90(10):1057–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Renzo G. C., Giardina I., Clerici G., Brillo E., Gerli S. Progesterone in normal and pathological pregnancy. Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation. 2016;27(1):35–48. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2016-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meis P. J., Klebanoff M., Thom E., et al. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348(24):2379–2385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero R., Nicolaides K. H., Conde-Agudelo A., et al. Vaginal progesterone decreases preterm birth ≤ 34 weeks of gestation in women with a singleton pregnancy and a short cervix: an updated meta-analysis including data from the OPPTIMUM study. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016;48(3):308–317. doi: 10.1002/uog.15953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saccone G., Khalifeh A., Elimian A., et al. Vaginal progesterone vs intramuscular 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for prevention of recurrent spontaneous preterm birth in singleton gestations: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2017;49(3):315–321. doi: 10.1002/uog.17245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rai P., Rajaram S., Goel N., Ayalur Gopalakrishnan R., Agarwal R., Mehta S. Oral micronized progesterone for prevention of preterm birth. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2009;104(1):40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbosa M. W. P., Silva L. R., Navarro P. A., Ferriani R. A., Nastri C. O., Martins W. P. Dydrogesterone vs progesterone for luteal-phase support: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2016;48(2):161–170. doi: 10.1002/uog.15814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fatemi H. M. The luteal phase after 3 decades of IVF: what do we know? Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2009;19(supplement 4):p. 4331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Funnel plots: risk of miscarriage in pregnant women experiencing threatened abortion based on the route of progesterone administration.

Supplementary Figure 2: Funnel plots: subgroup analyses of risk of miscarriage according to eligibility criteria, vaginal progesterone dose, and the study quality.