Abstract

Enterobactin is a secondary metabolite produced by Enterobacteriaceae for acquiring iron, an essential metal nutrient. The biosynthesis and utilization of enterobactin permits many Gram-negative bacteria to thrive in environments where low soluble iron concentrations would otherwise preclude survival. Despite extensive work carried out on this celebrated molecule since its discovery over 40 years ago, the ferric enterobactin complex has eluded crystallographic structural characterization. We report the successful growth of single crystals containing ferric enterobactin using racemic crystallization, a method that involves cocrystallization of a chiral molecule with its mirror image. The structures of ferric enterobactin and ferric enantioenterobactin obtained in this work provide a definitive assignment of the stereochemistry at the metal center and reveal secondary coordination sphere interactions. The structures were employed in computational investigations of the interactions of these complexes with two enterobactin-binding proteins, which illuminate the influence of metal-centered chirality on these interactions. This work highlights the utility of small-molecule racemic crystallography for obtaining elusive structures of coordination complexes.

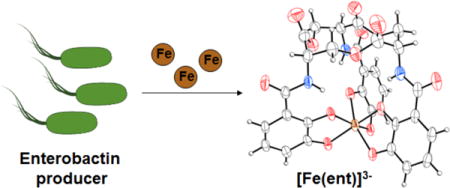

TOC image

Introduction

Iron is an essential metal nutrient for nearly all organisms. The ubiquitous use of iron in biology can be rationalized on the basis of its capability of performing chemical reactions that are required for life and its availability, which results from its abundance in the natural environment.1 Iron is the most abundant transition metal in the Earth’s crust.2 In aerobic solutions at neutral pH, iron exists predominantly as the insoluble ferric hydroxide (Ksp = 10−39).3 Thus, concentrations of aqueous iron available in the environment are substantially lower than the intracellular iron concentrations that are required by most organisms (1 μM-1 mM).4,5 Bacteria must obtain nutrient iron from the environment and, to overcome the low solubility of Fe(III), many bacteria biosynthesize and secrete siderophores, small molecule chelators that exhibit high affinity for Fe(III).6 Enterobactin (ent, Figure 1) is a triscatecholate siderophore produced by Gram-negative bacteria that include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Salmonella spp.7,8 Other bacterial species, such as Yersinia enterocolitica, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, do not produce enterobactin but express enterobactin receptors and are therefore able to import its iron complex as a xenosiderophore.9–11

Figure 1.

Deprotonation and binding of Fe(III) by enterobactin to give [Fe(ent)]3−. Highlighted: the primary triscatecholate coordination sphere (blue), the intramolecular secondary sphere interactions (red), and the trilactone backbone (green).

Enterobactin producers express an iterative non-ribosomal peptide synthetase that assembles enterobactin, a 12-membered cyclic trilactone with three pendent 2,3-dihydroxybenzamide (DHB) arms, from chrosimate and L-serine.12 Deprotonation of the DHB moieties generates three catecholate ligands that bind Fe(III) to afford a hexadentate coordination complex, [Fe(ent)]3− (Figure 1). This complex is recognized and bound by outer membrane siderophore transport machinery, which is expressed by enterobactin-utilizing microbes confronted with iron-limited conditions, and subsequently transported to the cytoplasm. One remarkable feature of enterobactin is the strength of its iron binding. With a reported formation constant of 1052, enterobactin is the strongest iron chelator yet identified in the natural world.13 Since its discovery, studies of enterobactin have elucidated many facets of its biology and chemistry, and provided the community with a textbook example of “metals in biology.” Moreover, investigations of its coordination chemistry have informed ligand design in transition metal and rare earth metal chemistry.14 In recent years, the importance of this molecule has been underscored by investigations revealing that enterobactin and related metabolites play important roles during bacterial infections, as well as the rise in antibiotic resistance in many bacterial pathogens that utilize enterobactin.15–20 Modified enterobactin scaffolds have been investigated as targeted antibiotic delivery vehicles.21–24

Decades of investigation have uncovered the coordination chemistry of enterobactin;4 however, despite over 40 years of research, the atomic-resolution structure of the complex has yet to be reported. Structural investigations on proteins that bind [Fe(ent)]3− have provided some snapshots of this coordination complex and its hydrolysis products, however. These studies have addressed siderocalin (Scn), a component of the mammalian immune system that binds to and prevents bacterial uptake of ferric triscatecholate siderophore complexes,25 as well as FeuA, a membrane transport protein that contributes to iron-uptake by Bacillus subtilis.26 The crystal structure obtained from co-crystallization of Scn and [Fe(ent)]3− suggests that the protein binds the siderophore complex at a three-fold symmetric pocket, but the macrolactone ring hydrolyzed during crystallization, which prevented an investigation of the structure of the metal complex.25 A crystal structure of FeuA·[Fe(ent)]3− was also reported but, as described below, the bound siderophore complex exhibits significant distortion from its equilibrium geometry, providing limited insight into its ground state structure.26

We report the successful growth of crystals containing [Fe(ent)]3− and describe the structure of this ferric siderophore as determined by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Successful crystallogenesis was achieved by racemic crystallization where the enantiomeric complex, ferric enantioenterobactin ([Fe(D-ent)]3−), was included in the crystallization conditions to provide a racemic mixture ([Fe(DL-ent)]3−). We compare the crystal structures to the structural information previously obtained from various spectroscopic, computational, and diffraction techniques. This structural analysis, coupled with theoretical calculations, provides insight into secondary coordination sphere hydrogen bonding interactions. Finally, protein-docking studies were conducted to investigate the interactions of both [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(D-ent)]3− with either Scn or FeuA.

Results and Discussion

Design

Because [Fe(ent)]3− had eluded crystallization, we considered departures from conventional strategies, including the methods used to crystallize analogous complexes.27–30 We first exchanged the potassium counterions introduced during the synthesis of [Fe(ent)]3− for tetraphenylarsonium ions, which confer excellent solubility in organic solvent and possess features that we reasoned would facilitate crystallization of the ferric siderophore complex. The tetraphenylarsonium ion is closer in volume to [Fe(ent)]3− than K+, rigid, highly symmetric (point group S4), and has a roughly spherical envelope. Moreover, it has a high concentration of arene rings that could participate in π-stacking interactions with [Fe(ent)]3−.

The most notable feature of our crystallization strategy was the deliberate attempt to co-crystallize [Fe(ent)]3− and its mirror image, [Fe(D-ent)]3−. This method, termed racemic crystallization,31 is based on the principle that chiral molecules crystallize more readily if they have the capacity to form a racemic crystal.32 A theoretical basis for such facilitated crystallogenesis has been proposed for macromolecular crystals, in which the number of intermolecular contacts is typically maximized.33 Centrosymmetry, permitted by the presence of both enantiomers, increases the number of rigid-body degrees of freedom, maximizing the number of contacts. Racemic crystallography has afforded crystal structures of proteins,34 peptides,35,36 nucleic acids,37,38 and supramolecular complexes39 in instances where enantiomerically pure compounds failed to yield diffraction-quality crystals. As opposed to protein crystals, which pack in a manner that maximizes the number of intermolecular contacts,34 the dominant factor in the crystallization of small molecules is the maximizing of close-packing.40,41 The cocrystallization of enantiomers allows for the presence of crystallographic symmetry elements such as glide planes and inversion centers that favor the closest packing of arbitrarily-shaped molecules,40,41 as in space group no. 14 (P21/c, P21/n), which is the most common among the small molecule crystal structures deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD).

Synthesis and Crystallization

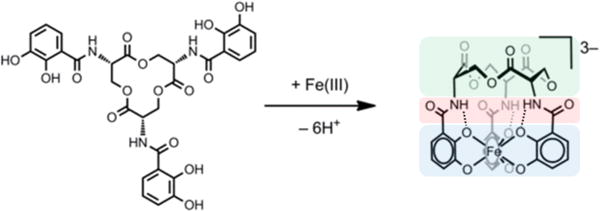

Enterobactin and enantioenterobactin were prepared as described previously from L-serine and D-serine, respectively.42 Deprotonation and metalation of a 1:1 mixture of enterobactin and enantioenterobactin provided the potassium salts of the ferric complexes.43 Salt metathesis with (AsPh4)Cl afforded (AsPh4)3[Fe(DL-ent)] as a deep red microcrystalline solid. This salt exhibits excellent solubility in alcohols and polar aprotic solvents, but is insoluble in alkanes, non-polar aromatics, water, and diethyl ether. High-resolution mass spectrometry confirmed the identity of the product as AsPh4+ and [Fe(DL-ent)]3− (Supporting Information). The optical absorption spectrum of (AsPh4)3[Fe(DL-ent)] exhibits the same features as that of K3[Fe(ent)], but the lack of circular dichroism (CD) features in the visible range for the former sample contrasts with their presence for the latter (Figure 2A and 2B). These results confirm that (AsPh4)3[Fe(DL-ent)] contains the desired enantiomeric coordination complexes in a 1:1 ratio.

Figure 2.

Characterization of [Fe(ent)]3−. (a) Optical absorption spectra of 200 μM [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(DL-ent)]3− in DMF. (b) Circular dichroism spectra of 5 mM [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(DL-ent)]3− in DMF. (c) Molecular graph of the ferric enterobactin complex anion with thermal ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level and hydrogen atoms shown as spheres of arbitrary radius. Color code: Fe orange, O red, N blue, C grey, H white. (d) Primary coordination polyhedron of [Fe(ent)]3− with blue faces, red spheres representing oxygen atoms at the vertices, and the central iron atom as an orange sphere. The individual angles averaged to obtain the twist angle α are indicated.

A variety of crystallization conditions were screened as described in the Supporting Information. Ultimately, deep red tablets were obtained over the course of two months by restricted vapor-phase diffusion of diethyl ether through a 1-mm diameter orifice into a DMF solution of the salt at −20 °C.

Crystal Structure

A suitable tablet was selected and analyzed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction. Indexing of the diffraction pattern afforded unit cell parameters consistent with a primitive monoclinic Bravais lattice and revealed that the broad parallel faces of the tablet comprise the basal pinacoid, form {001}, which is parallel to the crystallographic ab plane (Figure S1). Further analysis of the diffraction pattern revealed the Laue symmetry to be 2/m and the intensity statistics of the reflections suggest that the crystal is centrosymmetric (⟨|E2 − 1|⟩ = 0.862). Analysis of the systematically absent reflections indicated that the crystal formed in the centrosymmetric space group type P21/n (no. 14).

The structure was solved using intrinsic phasing44 and the ferric complex anion, three tetraphenylarsonium cations, a water molecule, and a DMF molecule were readily apparent in the electron density map (Figure S2). The tetraphenylarsonium cations demonstrate minimal π-interactions with each other, but participate in extensive π-interactions with the 2,3-DHB arms of [Fe(DL-ent)]3− (Figure S3). These π-interactions appear to be the dominant intermolecular forces present in the crystal. Details of the refinement are provided in the Supporting Information (Table S1). The composition of the crystal is assigned as (AsPh4)3[Fe(DL-ent)]·H2O·6DMF, which was corroborated by isopycnic flotation density measurements using 1,6-dibromohexane and hexane (Figure S4). All of the molecules in the crystal reside on general positions and the ferric complex is oriented with the pseudo three-fold axis approximately parallel to the crystallographic c axis (Figure S5).

Molecular Structure of Ferric Enterobactin

The [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(D-ent)]3− complexes are equivalent by crystallographic symmetry. Analysis will therefore be restricted to the naturally occurring enantiomer unless otherwise indicated. The Fe(III) complex is monomeric, featuring one iron atom chelated by a single hexadentate enterobactin ligand (Figure 2C). The ligand coordinates the metal with three bidentate chelate arms in a cis conformation, where the term cis indicates that the oxygen atoms at the ortho-positions of the 2,3-DHB arms bind at one facially-disposed set of coordination sites and those at the meta-positions bind at the remaining sites.45

Primary coordination sphere

[Fe(ent)]3− has chiral centers at each of the three serine units of the macrolactone ring as well as the tris-bidentate chelated metal center. The L-serine units necessarily have S stereochemistry, but the tris-bidentate chelated metal center could have either Δ or Λ stereochemistry depending on whether the three ligands are arranged in a right-handed or left-handed propeller, respectively. Spectroscopic comparison with model compounds indicates that [Cr(ent)]3− preferentially forms the diastereomer with Δ stereochemistry and NMR studies of [Ga(ent)]3− indicate that it forms a single diastereomer, albeit of unknown stereochemistry at the metal.46–48 Based on the similarities between these metal ions and Fe(III), [Fe(ent)]3− has been accepted to exist as a single diastereomer with Δ stereochemistry. Moreover, crystal structures of enterobactin complexes of V(IV), Si(IV), Ge(IV), and Ti(IV) show that these complexes all assume a Δ configuration.27,29,30,49 The present crystal structure affords a definitive Δ assignment to [Fe(ent)]3−, which is readily distinguished from [Fe(D-ent)]3− by the stereochemistry at the serine units (Figure 2C). The relationship between the CD spectra of [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(D-ent)]3− indicates that the handedness of the latter is opposite at the metal center.50 Indeed, in the present structure, [Fe(D-ent)]3− has Λ stereochemistry (Figure S6).

The present crystallographic data also provide a definitive assessment of the coordination geometry at the iron center. Early NMR studies used coupling constants from [Ga(ent)]3− to generate models of the structure of [Fe(ent)]3− with the assumption that the metal center has an octahedral geometry.46 Enforcing octahedral coordination, however, required severely distorted amide bonds. Subsequent crystallographic characterization of K3[Fe(catecholate)3] revealed that the metal center in this complex has a distorted octahedral geometry with D3 symmetry.48 The parameter that best describes this deformation is the twist angle α, which transforms from octahedral (α = 60°) to trigonal prismatic (α = 0°) (Figure 2D). For K3[Fe(catecholate)3], α = 44(1)°.48

Prior comparison of the electronic absorption and magnetic circular dichroism spectra of [Fe(catecholate)3]3− and [Fe(ent)3]3− suggested that the latter also features iron in an approximately D3-symmetric coordination sphere (distorted octahedral/trigonal prismatic).48,51 The crystallographic data confirm this assignment (Figure 2D) and provide an experimental twist angle of 36.6(3)°, which is close to the value predicted by molecular mechanics (α= 34.7°) and to that experimentally observed in a synthetic analogue of [Fe(ent)3]3− named [Fe(TRENCAM)]3− (α = 37.4°).28,52 In [Fe(ent)3]3−, the Fe–Oortho bonds are slightly longer (2.032(9)-2.041(8) Å) than the Fe–Ometa bonds (1.965(9)-2.0190(97) Å) and this variation can be attributed to second coordination sphere interactions as described below.

Secondary coordination sphere

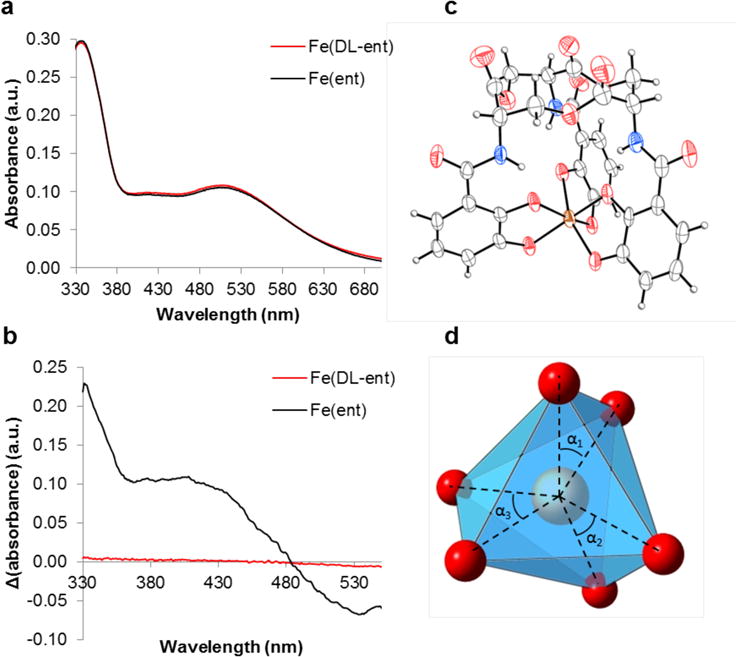

The amide groups deviate from planarity (ω = 170(1)°), but to less of an extent than the ≈90° initially predicted on the basis of an NMR analysis of [Ga(ent)]3−.46 The amide hydrogen atoms, which were explicitly located in the difference Fourier synthesis, form hydrogen bonds with the ortho oxygen atoms (Figure 3). The N–H–O angles, which range from 129.3-138.7°, deviate from 180°, but the N⋯O distances of 2.571(16)-2.639(16) Å are indicative of strong interactions (Table S3). An Atoms in Molecules analysis of the topology of the electron density of [Fe(ent)3]3− obtained from DFT calculations revealed (3, −1) N–H⋯O bond critical points with properties indicative of closed-shell donor-acceptor interactions (ρ = 0.049 au, ∇2ρ = 0.12) (Figure 3).53,54

Figure 3.

Second coordination sphere interactions. (a) Molecular graph of [Fe(ent)]3− with thermal ellipsoids drawn at the 50% probability level and intramolecular hydrogen bonds to amides and intermolecular hydrogen bonds to the water of crystallization (O3) shown as dashed lines. Fe⋯O1: 2.035(9) Å, Fe⋯O2: 2.0190(97) Å, Fe⋯O4: 1.965(9) Å, O3⋯O2: 2.67(2) Å, O3⋯O5: 2.86(2) Å, O3⋯O4: 4.29(2) Å. Color code: Fe orange, O red, N blue, C grey, H white (carbon-bound hydrogen atoms removed for clarity). (b) Ball-and-stick diagram of the computationally-optimized structure of [Fe(ent)]3− with a water molecule (O3) forming a hydrogen bond to O2. Fe⋯O1: 2.085 Å Fe⋯O2: 2.040 Å, Fe⋯O4: 1.990 Å, O3⋯O2: 2.750 Å. Identical color code. (c) Electron density (black) and associated gradient (blue) for the computationally-optimized structure of [Fe(ent)]3− without any additional intermolecular interactions. (3, −1) bond critical points are shown as blue discs, (3, −2) ring critical points as orange discs, and (3, −3) nuclear attractors as brown discs. Bond paths are shown as solid maroon lines and the van der Waals surface is highlighted with a thick black line. (d) Laplacian of the electron density with positive values contoured in solid lines and negative values contoured with dashed lines. Critical points and bond paths are indicated as in (c).

The crystal contains a water molecule in close proximity to the meta oxygen atoms of two of the 2,3-DHB arms (Figure 3). We suspect that the water molecule hydrogen bonds to the iron complex, but the hydrogen atoms on the water molecule could not be located in the difference map. Nevertheless, we do observe that the Fe–Ometa bond lengths for the arms in proximity to the water (2.019(9) and 2.01(1) Å) are longer than that of the remaining arm (1.966(8) Å). Geometry optimization of [Fe(ent)]3− in the gas phase reproduces the differential in Fe–O bond lengths between the meta and ortho positions discussed above. Re-optimization of the structure of [Fe(ent)]3− following explicit inclusion of a water molecule hydrogen-bound to one meta oxygen atom resulted in lengthening of the corresponding Fe–Ometa bond (Figure 3). Thus, when dissolved in water, the lengths of the Fe–Ometa and Fe–Oortho bonds become more similar. These results are consistent with EXAFS data of K3[Fe(ent)] recorded in the solid state and in aqueous solution.43,55

Macrolactone backbone

The projections of the carbonyl C–O vectors onto the pseudo C3 axis of the molecule are all directed away from the metal center. This macrolactone conformation has also been observed in crystal structures of (i) the parent serine trilactone and (ii) enterobactin complexes of Si(IV), Ti(IV), Ge(IV), and V(IV).29,30,56

In the present structure, the complex anion resides on a fully general position such that no crystallographic symmetry is imposed on the trilactone ring, which deviates significantly from three-fold rotational symmetry. This deviation is perhaps most evident in the orientation of the lactone carbonyl moieties, two of which are pointed outward from the center of the trilactone ring and one of which is pointed inward (Figure S3). The values of the various torsion angles in the enterobactin scaffold are consistent with the ranges expected from NMR coupling constants obtained with [Ga(ent)]3− (Table S2).46 These results indicate that although the chirality at the metal center is dictated by the structure of the trilactone, the backbone ring has a fair degree of flexibility, which could play a role in its interaction with proteins.

Protein Docking

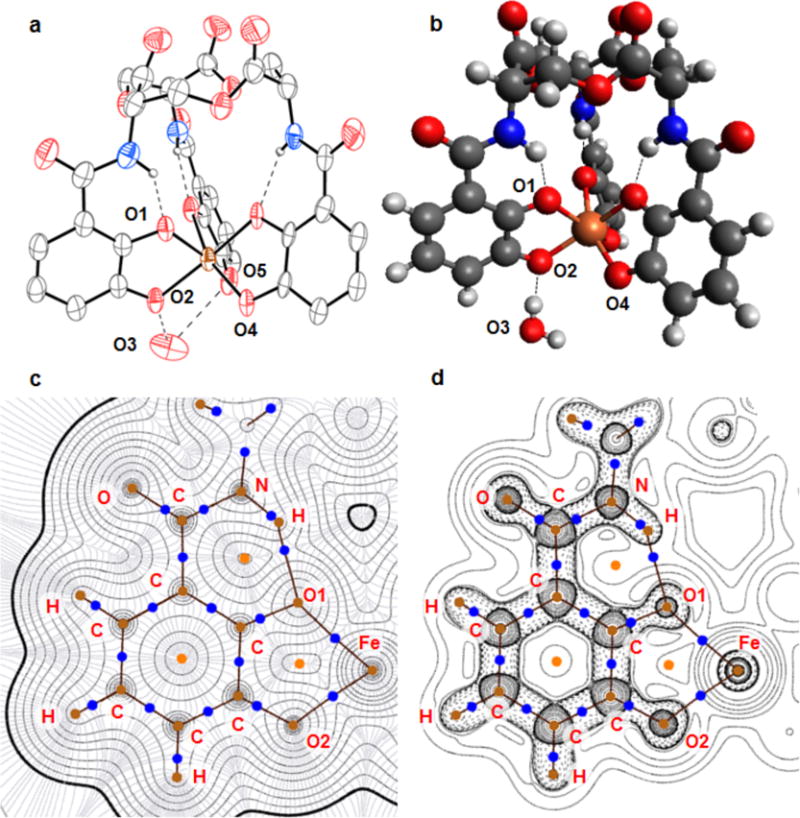

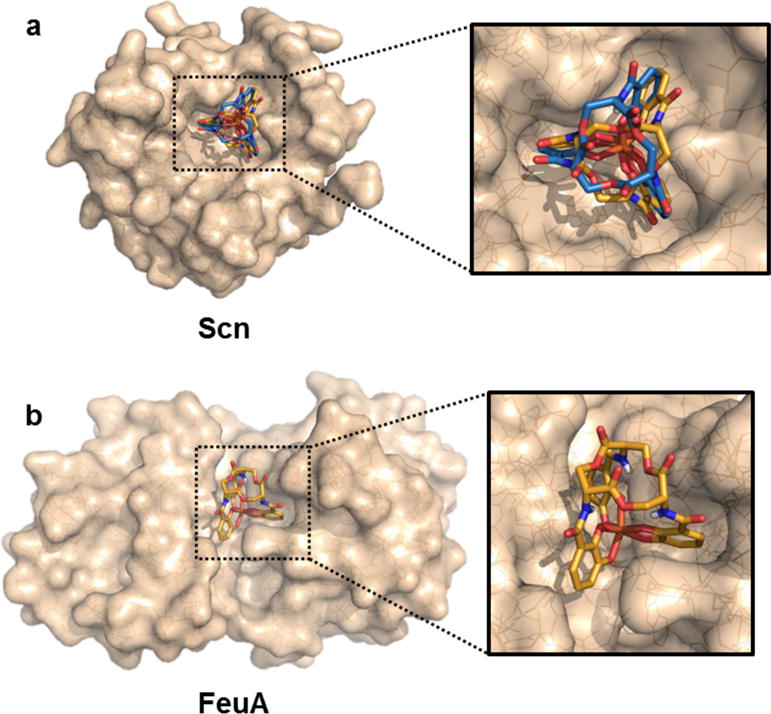

We employed the crystal structures of [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(D-ent)]3− to further evaluate the interaction of these complexes with two siderophore-binding proteins, Scn and FeuA. The crystal structure of Scn bound to hydrolyzed [Fe(ent)]3− indicates that the siderophore complex binds to the protein at a calyx bearing a triad of positively charged arginine and lysine residues that participate in cation–π interactions with the catecholate rings.25 Using the crystallographic geometries, [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(D-ent)]3− were computationally docked into apo Scn with both the protein and the ligand treated as rigid bodies. Both [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(D-ent)]3− bind in the calyx with the arginine and lysine residues of the protein positioned between the catecholate rings as observed in the crystal structure with hydrolyzed [Fe(ent)]3−. (Figure 4A). The estimated binding energies of the two enantiomers differ by less than 2.5 kcal mol−1, which is less than the estimated standard error for the docking program (Table S6).57 These results are consistent with the similar experimental binding affinities that Scn exhibits for [Fe(ent)]3− and [Fe(D-ent)]3−.58

Figure 4.

Protein docking studies with [Fe(D-ent)]3− shown as sticks with orange carbon atoms, [Fe(ent)]3− shown as sticks with blue carbon atoms, and proteins shown as translucent wheat surfaces encasing lines. (a) The crystallographically-determined structure of [Fe(D-ent)]3− docked into FeuA (PDB: 2XUZ). [Fe(ent)]3− could not be successfully docked into the binding site. (b) The crystallographically-determined structures of [Fe(D-ent)]3− and [Fe(D-ent)]3− docked into Scn (PBD: 1L6M).

FeuA is the cognate receptor for ferric bacillibactin, a triscatecholate siderophore complex similar to [Fe(ent)]3− but with a trilactone backbone comprised of threonine and a glycine spacer between the trilactone and 2,3-DHB of each arm. In contrast to ferric enterobactin, ferric bacillibactin has Λ chirality at the metal center. Biophysical studies indicate that FeuA binds preferentially to iron triscatecholate complexes with Λ chirality, but also coordinates [Fe(ent)]3− despite its Δ configuration in solution.59 The crystal structure of FeuA·[Fe(ent)]3− shows [Fe(ent)]3− in the same binding pocket that is occupied by ferric bacillibactin in the crystal structure of FeuA·[Fe(bacillibactin)]3−.26 The iron center in FeuA·[Fe(ent)]3− has a nearly trigonal prismatic coordination geometry with a slight Λ twist.26 Although all spectroscopic data indicate that [Fe(ent)]3− has Δ chirality in solution, this result indicates that FeuA distorts the coordination complex sufficiently to reverse the chirality at the metal center. Docking of [Fe(D-ent)]3− into apo FeuA resulted in binding in approximately the same manner as the distorted [Fe(ent)]3− from the protein crystal structure (Figure 4B, Table S6). We were unable to dock [Fe(ent)]3− as a rigid unit into the same binding pocket. In agreement with prior studies,59 these results highlight that FeuA is structurally preorganized to bind complexes with Λ chirality. These results allow us to predict that FeuA will bind [Fe(D-ent)]3− more strongly than [Fe(ent)]3−, an experiment that has, to the best of our knowledge, not yet been carried out.

Conclusion

We employed racemic crystallography to obtain single crystals of [Fe(DL-ent)]3− suitable for X-ray crystallographic structural determination. We believe that this strategy will prove useful in the structural characterization of other ferric siderophore complexes that prove to be difficult to crystallize. The structure of [Fe(ent)]3− provides a definitive confirmation of the accepted structure based on spectroscopic studies and comparison with other metal-bound forms of enterobactin. We have measured the key variable describing the distortion of the [Fe(ent)]3− coordination sphere, the twist angle α, which has been unattainable from previous spectroscopic studies. Intramolecular and intermolecular second coordination sphere interactions were found to have subtle, yet observable, influences on the primary coordination sphere. Finally, we computationally investigated the interaction of [Fe(ent)]3− with the proteins Scn and FeuA, and described these interactions as a function of the chirality of the metal complex. In closing, from a fundamental standpoint, it is gratifying to have realized the structural determination of this historically important complex. This work may also help to shed light on the interactions that occur between [Fe(DL-ent)]3− and proteins involved in bacterial iron acquisition and the mammalian immune response. Such information may contribute to the development of new strategies to combat pathogenic bacteria that rely on enterobactin and related metabolites for iron acquisition, many of which currently pose a significant health risk as we approach a post-antibiotic era.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the NIH (Grants 1R01AI114625 and 1R21AI126465) for financial support; Prof. D. W. Stephan for kindly providing access to an X-ray diffractometer, optical absorption spectrometer, and synthetic equipment; Prof. G. A. Woolley for access to a circular dichroism spectrometer; and Dr. P. Mueller for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

This Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website. Complete experimental methods, supporting tables, supporting figures, CIF.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lippard SJ, Berg JM. Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry. University Science Books; Mill Valley: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greenwood NN, Earnshaw A. Chemistry of the elements. 2nd. Butterworth-Heinemann; Oxford; Boston: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Latimer WM. The oxidation states of the elements and their potentials in aqueous solutions. Prentice-Hall, Inc; New York: 1938. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raymond KN, Dertz EA, Kim SS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630018100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnstone TC, Nolan EM. Dalton Trans. 2015;44:6320. doi: 10.1039/c4dt03559c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hider RC, Kong X. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27:637. doi: 10.1039/b906679a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Brien IG, Gibson F. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 1970;215:393. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(70)90038-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thulasiraman P, Newton SMC, Xu JD, Raymond KN, Mai C, Hall A, Montague MA, Klebba PE. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6689. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6689-6696.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schubert S, Fischer D, Heesemann J. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6387. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6387-6395.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poole K, Young L, Neshat S. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6991. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6991-6996.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biegel Carson SD, Klebba PE, Newton SMC, Sparling PF. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2895. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2895-2901.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrews SC, Robinson AK, Rodríguez-Quiñones F. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:215. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris WR, Carrano CJ, Cooper SR, Sofen SR, Avdeef AE, McArdle JV, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:6097. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raymond KN, Allred BE, Sia AK. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2496. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madhani HD, Skaar EP. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000949. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherayil B. J Immunologic Research. 2010;50:1. doi: 10.1007/s12026-010-8199-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts RE, Totsika M, Challinor VL, Mabbett AN, Ulett GC, De Voss JJ, Schembri MA. Infect Immun. 2011;80:333. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05594-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagy TA, Moreland SM, Andrews-Polymenis H, Detweiler CS. Infect Immun. 2013;81:4063. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00412-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nairz M, Schroll A, Haschka D, Dichtl S, Sonnweber T, Theurl I, Theurl M, Lindner E, Demetz E, Aßhoff M, Bellmann-Weiler R, Müller R, Gerner RR, Moschen AR, Baumgartner N, Moser PL, Talasz H, Tilg H, Fang FC, Weiss G. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:3073. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palacios M, Broberg CA, Walker KA, Miller VL, D’Orazio SEF. mSphere. 2017;2:e00341. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00341-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng T, Bullock JL, Nolan EM. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18388. doi: 10.1021/ja3077268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng T, Nolan EM. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9677. doi: 10.1021/ja503911p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng T, Nolan EM. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25:4987. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji C, Juárez-Hernández RE, Miller MJ. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:297. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goetz DH, Holmes MA, Borregaard N, Bluhm ME, Raymond KN, Strong RK. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1033. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peuckert F, Ramos-Vega AL, Miethke M, Schwörer CJ, Albrecht AG, Oberthür M, Marahiel MA. Chem Biol. 2011;18:907. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karpishin TB, Raymond KN. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1992;31:466. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stack TDP, Karpishin TB, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:1512. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmiederer T, Rausch S, Valdebenito M, Mantri Y, Mösker E, Baramov T, Stelmaszyk K, Schmieder P, Butz D, Müller SI, Schneider K, Baik M-H, Hantke K, Süssmuth RD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:4230. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baramov T, Keijzer K, Irran E, Mösker E, Baik M-H, Süssmuth R. Chem–Eur J. 2013;19:10536. doi: 10.1002/chem.201301825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berg JM, Goffeney NW. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matthews BW. Protein Sci. 2009;18:1135. doi: 10.1002/pro.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wukovitz SW, Yeates TO. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:1062. doi: 10.1038/nsb1295-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeates TO, Kent SBH. Annu Rev Biophys. 2012;41:41. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-050511-102333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pentelute BL, Gates ZP, Tereshko V, Dashnau JL, Vanderkooi JM, Kossiakoff AA, Kent SBH. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9695. doi: 10.1021/ja8013538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CK, King GJ, Northfield SE, Ojeda PG, Craik DJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:11236. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mandal PK, Collie GW, Kauffmann B, Huc I. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:14424. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandal PK, Collie GW, Srivastava SC, Kauffmann B, Huc I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:5936. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandal PK, Kauffmann B, Destecroix H, Ferrand Y, Davis AP, Huc I. Chem Commun. 2016;52:9355. doi: 10.1039/c6cc04466b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kitaigorodskii AI. Organic Chemical Crystallography. Consultants Bureau; New York, NY: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kitaigorodskii AI. Molecular Crystals and Molecules. Academic Press; New York, NY: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramirez RJA, Karamanukyan L, Ortiz S, Gutierrez CG. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:749. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abergel RJ, Warner JA, Shuh DK, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8920. doi: 10.1021/ja062046j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sheldrick GM. Acta Crystallogr Sect A. 2015;71:3. doi: 10.1107/S2053273314026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leong J, Raymond N. J Am Chem Soc. 1975;97:293. doi: 10.1021/ja00835a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Llinás M, Wilson DM, Neilands JB. Biochemistry. 1973;12:3836. doi: 10.1021/bi00744a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Isied SS, Kuo G, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:1763. doi: 10.1021/ja00423a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raymond KN, Isied SS, Brown LD, Fronczek FR, Nibert JH. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:1767. doi: 10.1021/ja00423a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karpishin TB, Dewey TM, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1842. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abergel RJ, Zawadzka AM, Hoette TM, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12682. doi: 10.1021/ja903051q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karpishin TB, Gebhard MS, Solomon EI, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:2977. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hay BP, Dixon DA, Vargas R, Garza J, Raymond KN. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:3922. doi: 10.1021/ic001380s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bader RFW, Essén H. J Chem Phys. 1984;80:1943. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zou J-W, Huang M, Hu G-X, Jiang Y-J. RSC Adv. 2017;7:10295. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abergel RJ, Clifton MC, Pizarro JC, Warner JA, Shuh DK, Strong RK, Raymond KN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11524. doi: 10.1021/ja803524w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shanzer A, Libman J, Lifson S, Felder CE. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:7609. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trott O, Olson AJ. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Abergel RJ, Wilson MK, Arceneaux JEL, Hoette TM, Strong RK, Byers BR, Raymond KN. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A. 2006;103:18499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607055103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peuckert F, Miethke M, Albrecht AG, Essen L-O, Marahiel MA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:7924. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.